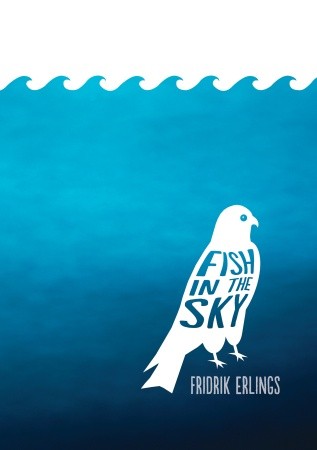

The novel Góða ferð, Sveinn Ólafsson (1998), translated to English by the author and Lucy Culthew.

From Fish in the Sky:

1.

I am a star, a twinkling star. I’m an infant on the edge of a grave and an old man in a cradle, both a fish in the sky and a bird in the sea. I’m a boy on the outside, but a girl on the inside; innocent in body, guilty in soul.

Light seeps through my eyelids, I blink twice and glance at the alarm clock. It’s exactly thirteen years and twenty four minutes since the moment I was born into this world, on that cold February morning, when a Beatles song played for Mum on the radio. She went into labour and the midwife came running into the room, arriving almost too late because she’d got stuck in a snow drift on the way, and screamed, “You're not seriously thinking of giving birth in this weather, are you?”

Love, love me do. You know I love you. I’ll always be true. So please love me do. She and Dad had danced to that song nine months earlier at some ball somewhere and it had since become their song.Then it became my song.

I’m a year closer to being considered a grown up, as Mum likes to put it, with a shadow of apprehension in her voice. But until then I’m just as far from being considered a grown up as I am from being a child; I’m the missing link in the evolution of Homo sapiens.

I sit up in my blue-striped pyjamas and look around. My desk is still in its place under the window, the bookshelves by the wall, the fish tank on the chest of drawers in the corner. Everything is as it should be. Nothing has changed, and yet it’s as if everything has changed.

Then I notice a cardboard box in the middle of the floor, that wasn’t there when I went to bed. It’s about seventy centimetres high and forty wide, tied with string and brown tape, battered looking with dented corners and oil stains, as if it has been stored in a ship’s engine room for a long time. Which it obviously had. This could only be a gift from Dad that someone has snuck into my room after I fell asleep. Dad’s parcels haven’t always arrived on the right day. Sometimes they don’t arrive at all. But he’s always sent me a postcard, wherever he goes. Dad works on a big freighter and sails all over the world, I get cards from Rio, Hamburg, Bremen, Cuxhaven and places like that, and I put them all up on the wall over my bed. I know it’s not always easy for a sailor to get to a post office on time to send a card or a parcel.I could easily understand that. But what was more difficult to figure out was why Dad seemed to be so much further away from me when he was ashore. But then when I think about that I turn into a girl inside and get tears in my eyes at the thought that Dad’s gift has arrived at all, and what’s more on the right day.

It’ll soon be a year since I last saw him. He’d shown up with my birthday present three weeks late and was drunk and demanded coffee. Mum scolded him like a dog for turning up in such a state and setting such a terrible example, now that he was finally making an appearance, and asked him if there was a rule against phoning from those ships, and whether he couldn’t at least have tried to call me on the day of my birthday. He apologised profusely and said they couldn’t, it wasn’t his fault, those were the regulations. Then he bent over and kissed me on both cheeks and the stench off him was so strong I could still smell it in my hair after he had gone; a powerful mixture of Old Spice and beer of course. He plonked one hand on my shoulder and the other on my head. His eyes were swimming so much I was afraid they’d pop out of their sockets. He couldn’t focus straight and his eyelids drooped heavily.

“I’ll be back on shore very soon, be a good lad. We’ll go to the cinema, would you like to go to the cinema? That’s settled then, I’ll come over and we’ll go to the cinema,” he’d whispered.

Then Mum closed the door and he stood there in front of it, muttering something and then staggered into the taxi that was waiting for him outside.That was almost a year ago.

It’ll soon be a year since I last saw him. He’d shown up with my birthday present three weeks late and was drunk and demanded coffee. Mum scolded him like a dog for turning up in such a state and setting such a terrible example, now that he was finally making an appearance, and asked him if there was a rule against phoning from those ships, and whether he couldn’t at least have tried to call me on the day of my birthday. He apologised profusely and said they couldn’t, it wasn’t his fault, those were the regulations. Then he bent over and kissed me on both cheeks and the stench off him was so strong I could still smell it in my hair after he had gone; a powerful mixture of Old Spice and beer of course. He plonked one hand on my shoulder and the other on my head. His eyes were swimming so much I was afraid they’d pop out of their sockets. He couldn’t focus straight and his eyelids drooped heavily.

“I’ll be back on shore very soon, be a good lad. We’ll go to the cinema, would you like to go to the cinema? That’s settled then, I’ll come over and we’ll go to the cinema,” he’d whispered.

Then Mum closed the door and he stood there in front of it, muttering something and then staggered into the taxi that was waiting for him outside.That was almost a year ago.

(pp. 9-11)