Bio

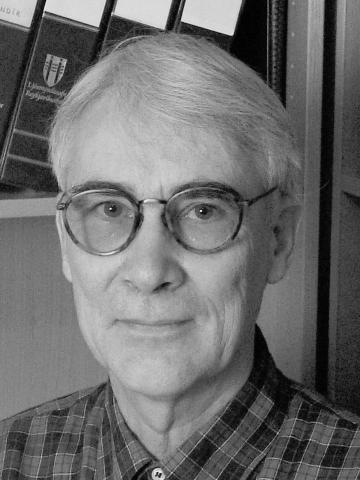

Andrés Indriðason was born in Reykjavík on the 7th of August 1941. He has worked as a journalist, teacher, television producer, film maker and writer. He has also translated a large number of books and television programs. Andrés studied English at the University of Iceland from 1963-1964 and film-making and TV-production in Århus, Denmark, and in Copenhagen from 1965 to 1966. He worked as a TV-producer for the Icelandic Broadcasting Company from 1965-1985. Since then he has worked as a writer, a freelance producer and at film-making as a director and script-writer.

Andrés has written numerous novels and plays for radio, television, and the stage. His first book, Lyklabarn (Keychain-Child), received first price in Mál og menning Children's Literature Award in 1979 and was consequently published by the same publishing house. His second book, Polli er ekkert blávatn, received The Reykjavík Education Council Award as the best children's book in 1981. Andrés Indriðason's books have been published in Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Denmark. His radio plays have been broadcast in all the Nordic countries, and his television films for children have been shown all around the world. Some of his films have also been used as teaching material in Iceland and abroad.

Andrés Indriðason died on July 10th, 2020.

From the Author

My relationship with fiction - or writing

Suddenly this idea was born. From nowhere really. Not because I heard something or saw something. It just came and wouldn't go away. I was sitting in a half-lit cinema auditorium watching the silver screen which was waiting to be struck by rays of light with moving pictures, when an invisible ray of light entered me. Images had entered me and would not leave, however much I tried to push them away. They were incredibly good images and before I knew it I had fished a crumpled piece of paper out of my pocket and started writing. The paper didn't allow many words, but that didn't matter. I had not started writing the story. I was just an idea. Two sentences were enough. They were the spark that would later kindle the blaze.

Darkness descended and the cinema screen came to life. I tried to make contact with the people who appeared before my eyes, tried as hard as I could, but it was all in vain. Yet these were famous actors and the story seemed promising. My own idea for a story wouldn't leave me in peace. It wanted me to attend to it. Wanted me to give it precedence over everything else. And it got its own way. I leaned back in my seat, watched the screen but could not see what was going on. Just the vague outlines of something moving. But I could see my own images clearly and distinctly. My own story. Wished that I could write more, much more on the piece of paper, but had to accept the fact that I was not at my desk at home, but in a cinema.

I had a cinema in my own head. A story that I saw in pictures like a film. It was beyond my control. The idea had become a draft with a beginning, a middle and an end according to the laws of narrative. More to the point it effortlessly divided itself into chapters all by itself and sent the characters to me. I could see them as large as life. They all wanted to enter the story but only the ones that suited the subject could be admitted. That was obvious. There were four of them. I thanked all the others for coming. Wondered what the story ought to be called, but abandoned such thoughts after a short while. I ought to know by know that more often than not it is pointless to give a title to a work of fiction in its earliest stages.

was pleasantly surprised by what a good story it was. It was just as if I had been working on it before, had analysed every detail, because everything fell so easily into place. Yet it was out of the question that I had thought about this subject for a story before. I had never once crossed paths with those characters. I caught myself smiling to myself, it was such ecstasy. It was a good story. A story that is relevant to readers. A story about serious issues. Lyrical and funny. I looked forward to going home and sitting down at my computer.

I sank into thoughts about narrative technique and style, but was roused from them with a start when the lights suddenly went on in the auditorium. Why do they always need to have intermissions in the cinema? Why do they need to disturb people when they are feeling comfortable? What is that sort of harassment supposed to mean? I wasn't asking for popcorn and coke.

I spoke to people I bumped into during the intermission, but couldn't hear myself. I didn't know whether I even knew them. I just saw them as silhouettes. Now there were two versions of me. One was talking about this and that to the silhouettes. The other was up in the clouds and could hear nothing but murmuring and roars of laughter and the rustling of bags of popcorn. The characters in my story did not want an intermission. They just wanted to go on existing. They don't like popcorn either.

Suddenly the life of one of the characters changed. I was on my way back into the auditorium when it happened. This was a woman of around thirty who likes rollerblading along the paths by the shore in the west of town. She crashed into a dog that suddenly jumped into her path. She fell over and her life took a new course. And the story.

I was relieved when the darkness descended and the second half of the film resumed, relieved to have shaken off the second version of myself, relieved to be able concentrate on my people. I watched a black cat sneaking across the screen in the moonlight and I shut my eyes when a new day dawned in the film. It didn't matter if I lost that thread. It was my thread that mattered. My people. My story.

I thought about the woman who fell over when rollerblading. I had her fate in my hands. I could decide how she fared when the dog jumped in front of her and butted her. The author ahs absolute control over his characters. They have to sit and stand exactly as he wants them to. I decided it was a serious accident, so serious that the woman would lose her footing in life. Of course, that had an effect. The story gained depth. The ending improved. It became more dramatic. Admittedly a few secondary characters had to be scrapped, but they weren't missed.

When I had gone back home and sat down at my computer, when I had left the semi-darkness of the cinema, turned on the computer and written Story in December – first idea, when the screen was waiting to be swamped with the whole flood of ideas so that the computer could commit it to memory and make the rest easier for me, when this moment I had eagerly been waiting for finally arrived, I suddenly couldn't feel any more the currents that had captivated me in the cinema. I looked at the piece of paper I had written on, a crumpled counterfoil of an Air Iceland ticket to Akureyri, seat number 9A, and felt that the spark was extinguished. The spark that should have kindled the blaze. The spirit that came over me must have been teasing me. No. It had seen the story in a new light, seen that it was a load of nothing, seen the hopelessness of the situation and fled. That was the explanation.

I had come back down from the clouds. Couldn't touch the computer even if I wanted to. My fingers didn't reach the keyboard. I was like a burst balloon. Can't make head nor tail of myself. Why did I let such absolute nonsense lead me astray like that?

I switch off the computer and hear voices saying that it was a particularly good film. Brilliant actors, a brilliant story. That it was nice meeting Jónsi and the others in the intermission. That it's always such fun to go to the cinema. I agree and can't help smiling even though the brilliant film passed me by completely that time. Yes, it's fun to go to the cinema, I say, as I ask myself why I'm always getting these ideas. These crazy ideas. Why am I always writing? Am I normal? Are all writers like this, or just me?

But of course I receive no reply.

Andrés Indriðason

Translated by Bernard Scudder

About the Author

María Bjarkadóttir: On the works of Andrés Indriðason

Andrés Indriðason has, since the publication of his first children's book, Lyklabarn (Keychain-Child, 1979), been a proliferate author of books for children and young adults. He has written a number of books for kids aged seven and older, as well as translating books, writing scripts for television shows and films, plays, radio plays and song lyrics. His books have received numerous awards and have always been very popular among readers. Most of Andrés's books touch on similar themes, which have to do with becoming an adult, taking on responsibility and standing on your own two feet. Most of them are written in a realistic style, the problems the kids face are everyday problems, which happen in an everyday environment and could happen to anyone.

His books that appeal to younger readers, like Lyklabarn, Polli er ekkert blávatn (Kiddo Can Do It, 1981), Elsku barn (My Dear Child, 1985), Tröll eru bestu skinn (Trolls Are Not Too Bad, 1985) og Það var skræpa (The Best Pigeon in the World, 1993) are about children that no one has time for; children who have parents who are divorced or are about to divorce; about what it is like to move to a new place where you do not know anyone and what it feels like to be left out. In those books, Andrés criticizes society and Lyklabarn is the clearest example of that. The parents in the book have no time for their children. Dísa and her brother are alone all day, and must take care of themselves, but Dísa is much too young to shoulder the responsibility that her parents are expecting of her. Lyklabarn is also one of the few books by Andrés that does not have a traditional ending where everything is resolved, since Dísa's parents fail to see the error of their ways.

In his books about younger teenagers, Andrés generally chooses to write about one central character, usually a boy around confirmation age (14 in Iceland). Andrés usually follows the same character through a few books, humorously depicting how he matures and deals with life. In spite of the lightness of tone in the books, there are often more serious issues under the surface, particularly in the trilogy about Elías, Viltu byrja með mér (Do You Want to Go With Me?, 1982), Fjórtán bráðum fimmtán (Fourteen, Almost Fifteen 1983) and Töff týpa á föstu (A Cool Guy Going Steady, 1984), which were tremendously popular when they came out.

In these books, Elías develops from being a kid that no one listens to, into a teenager. After his dad dies, he proves to his mum that he can be trusted for many things and also manages to prove to his bigger brother that he is not a kid anymore. Elías also has to deal with the world outside the home, make decisions about whether he wants to smoke and drink, like the kids in the new school he goes to and about which girl he really fancies the most.

The books Bara stælar (Just Kidding, 1985), Enga stæla (No Kidding, 1986) og Stjörnustælar (Star Complex, 1987) are about Jón Agnar who moves to Reykjavík from the Westman Islands and has great trouble at first adjusting to his new classmates and his new life in Reykjavík. The style of these books is much ligther than in the books about Elías, as Jón Agnar is more of a joker and a humorist. He gets into one awkward situation after another, and seems to fully enjoy himself. Yet, there is always the underlying fear of ostracism, of not meeting the other kids' standards and being teased. As in some of Andrés's other books, the solution to his problems seems to be an increased confidence, which many of his characters seem to have in limited supply at the beginning of the books. When they learn to accept themselves, stand on their own two feet and withstand the peer pressure, their lives in most cases improve dramatically.

In these books, the main characters often experience their first love, although it is not necessarily their last, as the books are completely void of any romantic notions. They also go through feelings of being alone and ostracism after moving to a new area or a new part of the country and they encounter conflict at home when they begin to make claims for the grown up existence that was promised to them at confirmation.

It is also worth mentioning two books that deal with similar things but are still very different from the others; the short story collection Mundu mig, ég man þig (Remember Me, I Will Remember You, 1990), a collection of stories for children and adolescents that deal with serious issues; and Ævintýralegt samband (An Fantastical Connection, 1997), which tells the story of the teenage boy Álfur, who is in fact an elf, but he lives in the human world and is not aware of it. This story is more fantastical than other of Andrés's stories, even if it is told in a realistic style.

The books that are about older teenagers are much more serious than the other ones. The main characters are around eighteen years of age and the protagonist is more often a girl than a boy, although sometimes the point of view jumps between a boy and a girl. In some respect these books deal with the same problems as those of his books that deal with younger teenagers, but here the problems have become much more serious. First love is not quite as innocent in these books as for example for Jón Agnar, and the parties are different. They also deal with crime, both crimes committed by the teenagers and crimes committed against them.

The books Með stjörnur í augum (With Stars in the Eyes, 1986) and Ég veit hvað ég vil (I Know What I Want, 1988) are about Sif who is 17 and falls hard for Arnar, the coolest bloke in the school. After a brief relationship, which ends with Arnar coercing her to sleep with him, Sif becomes pregnant but Arnar runs away. The second book is about both of them and how they deal with their changed situation; its central theme is choice and making the right choices for the future. Arnar figures it out by the end of the book and they decide to give their relationship another chance, both having become a great deal older and more mature than they were at the beginning of the first book. The light tone that characterized the books about younger teenagers is completely gone in these books and the seriousness of life has taken over. The style is even more realistic than in the other books, as you can not scramble your way out of a situation with humour or luck. You need to deal with life as it comes, and take responsibility for your actions.

Most of Andrés's books for young adults have a contemporary setting. They are placed squarely within the times they were written in, featuring references to pop lyrics and films, night clubs and descriptions of the kids' hair styles and clothes. The language used is peppered with slang but these factors have unfortunately caused the books to age rather badly, as very few teenagers today recognize the films and styles that were prevalent in the eighties, and the character descriptions and their manner of speaking just becomes plain funny. Sólarsaga (The Whole Story, 1989) for example describes a boy as being a real "comatose" (p. 87). The reader may also find it strange that a character in a book about teenagers is "68 make" (Ég veit hvað ég vil p. 124), although it no doubt sounded well when the book came out. Those of the author’s more light-hearted books, like the ones about Jón Agnar, escape more unscathed than the serious ones, because the humour counterbalances the things that may baffle the reader.

However, it was probably this connection with current affairs, that was the key to Andrés' enormous popularity. The books appealed to kids and teenagers at the time and Andrés showed that he knew what was happening in society from the point of view of teenagers, which films to see, which music to listen to and how to dress. Besides, the books do not for the most part have any preaching tone, and generally the teenagers are left to be teenagers in peace. Voices of reason and of the world of the grown ups are still present, although fathers are usually absent, but mothers give good advice when they can find the time for it. When all else fails, it is usually the head master of the main character's school, who becomes the most important listener and counsellor.

Two of Andrés's books for teenagers distinguish themselves from the rest: the historical novels Allt í besta lagi (Everything Fine 1992) and Manndómur (A Real Man, 1990). Allt í besta lagi is about Keli who lives in Reykjavík in the post-war years. He lives with his family in an army bunker and his life is very much coloured by the life in the neighbourhood. School has closed for the summer and while he waits for it to begin again, he works as a delivery boy in a grocery shop. On one of his deliveries, he meets Inga Dóra who later becomes his girlfriend. The narrative is light-hearted but here as always things take a more serious turn when Keli finds a wallet on the shop floor and fails to hand it over to the shop owner despite repeated efforts. Around the same time, his sister Lína returns home after a failed marriage and her rough husband follows her, turning things upside down in the home. Just like many other teenagers in Andrés's stories, Keli does not enjoy much understanding from his parents, the dad is distant and mum does not understand him. All of this is more noticeable because of the crammed living quarters of the family. No one can have any peace for long and those who want to stay at home have to tolerate all the others.

Although the setting is different than in other of Andrés's books, Allt í besta lagi still bears all the hallmarks of the other stories in the sense, that it tackles typical teenage problems, even though the story has been spiced up with the extra tension that the lost wallet creates. The story also ends conventionally with all the problems being resolved, but the setting and the time makes it more interesting.

Even less like the rest of Andrés' books is Manndómur, which is set during the war years in Reykjavík. This is the story of Kalli, who lives with his parents and brother in an apartment block and the family is fairly well off, compared to many others at the time. But everything turns chaotic at home when Kalli's dad loses his job and starts to drink. Kalli must find a job and despite his dad's abhorrence of the occupying force, he starts to work for the British troops. Around that same time, he meets Dagný, who becomes his girlfriend and who lives with her sister in a small basement flat on the west side of town. The problems addressed in Manndómur are unlike those we have previously seen from Andrés. Many of those are the typical teenage problems that everyone has to deal with, but there are also things that happen, which are more tragic than in other books by Andrés. The setting and the spirit of the times described here also make the majority of Kalli's problem seem alien to the modern reader, an example of this is the unemployment of Kalli's father. Discussion about what was called "the situation", when Icelandic women (and men) had various relations with the soldiers of the occupying forces, often regarded with suspicion, even anger, by other inhabitants of the city, also becomes important; seen through both the negative eyes of Kalli's father, and the positive eyes of his co-workers.

Kalli's girlfriend and her sister are both involved in this "situation", along with his co-worker. Dagný betrays Kalli for a soldier, and this world of betrayal and secret activity is alien to Kalli who is only fifteen, although most people take him to be at least seventeen. The girlfriend's betrayal and that of his co-worker, who gives a him a stolen bicycle, and his father's U-turn from being a downtown drunk to finding religious salvation, proof to be too much for Kalli, who commits a crime in a drunken rage. Many things in Manndómur are suggested rather than said directly, for instance when it comes to Dagný and her sister Dísa's relations with the soldiers. Dagný reassures Kalli that all is completely innocent between them and the soldiers, but one of them stays in their flat all the time and later Kalli runs into the same man visiting his co-worker, who provides the soldiers with liquor and girls. There are suggestions that things are not all right with the sisters but the reader's suspicion is never fully confirmed, despite the fact that Dagný is dating a soldier by the end of the book. There are also suggestions that Kalli is really losing his mind. He himself wonders about it and his behaviour towards the end becomes quite strange. At the end of the book we leave Kalli, as he is escorted by the police, heading for prison, after having committed a heinous crime, thereby catching both the reader, other characters in the book and himself by surprise.

Andrés Indriðason has written one book aimed at adult readers. The book has the title Maður dagsins (Man of the Hour, 1982) and is the story of Bárður, who is 22 years old, has just moved to the city from out of town and is a newly discovered long jumping genius. Bárður is innocent and inexperienced and even if it is never said directly, his thoughts and behaviour, as well as other people's attitude towards him, frequently suggest that he is not as mentally developed as the average Joe.

The book is largely told in the third person narrative and every now and then, there are chapters written in the style of a sports news coverage, and this allows the reader to follow Bárður's achievements. The narrative regularly moves into the second person narrative, and then Bárður's second self is apparently giving him advice and telling him how he should behave. Bárður repeatedly gets into situations that he can not or does not know how to deal with, most of them relating to his newfound fame and in those cases, his second self takes over and orders him around. This behaviour gives the reader the impression that Bárður is mentally unstable and that suspicion is confirmed, by events that seem to take place mainly inside his head. These events relate to himself but they make him more of a hero in his own mind than he really is, whether he brings a woman home or throws a tantrum at work. In those cases, the line between reality and what is only happening inside Bárður's head becomes a bit blurred.

This book is obviously critical of the world of sports and how outside interests use sport as a promotional vehicle for themselves and their allies. Bárður is mobbed by entertainers, shop owners and politicians who all want to use him to advertise themselves and their interests and he, not fully comprehending this world, does not know how to deal with this or avoid it.

In his books, Andrés Indriðason shows great versatility and his books can be both funny and serious at the same time, depending of the subject matter of each book. He openly addresses problems like drinking, divorce and young parents and sometimes the main characters are the source of these problems, sometimes they are just onlookers. The reader does not get the feeling that s/he is being lectured, but rather that these issues are simply being put to his attention. The emphasis is still on the entertainment value and the characters are made to be likeable. Although many of Andrés' books have aged badly, many of them still have relevance. Addressing issues like peer pressure and the fear of not being like others is always important and thus it does not really matter if the characters go to see a film that no one remembers anymore.

© María Bjarkadóttir, 2003.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Articles

Criticism

"Bíblíografítsjeskíj slovar"

Detskaja líteratúra 1996; no. 4-6, pp. 79-83.

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 602-3, 605.

Awards

1984 - The National Centre for Educational Material: First prize in a competition about reading material for beginners for the children´s book Það var skræpa (The Best Pigeon in the World)

1982 - Reykjavík City Children´s Literature Prize: Polli er ekkert blávatn (Polli er ekkert blávatn)

1979 - Mál og menning Children´s Literature Competition: Lyklabarn (Latchkey Kid)

1990 - IBBY Iceland Award: Manndómur (Manhood)

Lestrarlandið (Readingville)

Read moreSól og blíða í Paradís (Sunshine in Paradise)

Read moreSannleikurinn og lífið (The Truth and the life)

Read moreÍ Undralandi (In Wonderland)

Read more

TX-10: Í skólanum (TX-10: In School)

Read moreTX-10: Í fótbolta (TX-10: Playing Soccer)

Read moreHúsið á Eyrarbakka (The House at Eyrarbakki)

Read more

Lukkudýrið (The Mascot)

Read moreTX-10: Það er ég (TX-10: That's me)

Read more

Búrkína Fasó (Burkina Faso)

Read more

Eva og Adam : Kvöl og pína á jólunum (Eva och Adam - Jul jul pinsamma jul)

Read moreReiknibíllinn : Það er leikur að reikna (The Mathmobile : Math is Easy)

Read more

Eva og Adam : Með hjartað í buxunum (Eva och Adam - Fusk og farligheter)

Read more

Eva og Adam : Bestu óvinir (Eva och Adam - Bästa ovänner)

Read more

Rasmus klumpur á pínukrílaveiðum (Rasmus klumpur Hunts Tinytrolls)

Read more

Rasmus klumpur í Kynjaskógi (Rasmus klumpur Goes to Troll´s Forest)

Read more

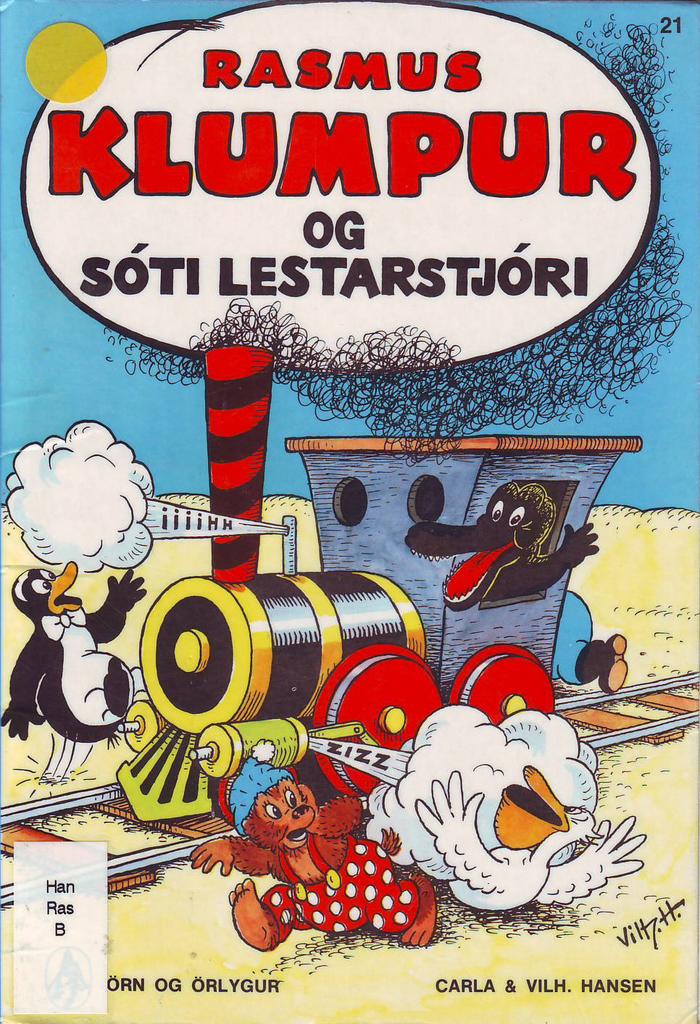

Rasmus klumpur og Sóti lestarstjóri (Rasmus klumpur Meets the Train Conductor)

Read moreRasmus klumpur í undirdjúpunum (Rasmus klumpur Goes Diving)

Read more