Bio

Áslaug Jónsdóttir was born on March 31 1963. She grew up on the farm Melaleiti in Borgarfjörður in the west of Iceland. She did her secondary studies at Menntaskólinn við Hamrahlíð in Reykjavík, graduating in 1983. She studied at the Icelandic College of Arts and Craft from 1984 - 1985 and then went abroad for further studies. She was a student at Skolen for Brugskunst - Danmarks designeskole in Copenhagen, graduating from the department of drawing- and graphic art in 1989. Áslaug has also taken several art courses in Iceland, Sweden and in the United States.

Since her graduation Áslaug has worked as an illustrator, graphic designer, writer and visual artist. She has written and illustrated numerous children's books and taken part in exhibitions in Iceland and abroad. She has also been a teacher at various art courses and given lectures at The Akureyri University, The University of Iceland, for Ung in the Faroe Islands to name a few. Áslaug has also written and illustrated children's programs for television. She was a news reporter for Morgunblaðið newspaper from 1996 - 1998 and wrote columns for the newspaper Dagur in 1998 as well as doing illustrations for the paper.

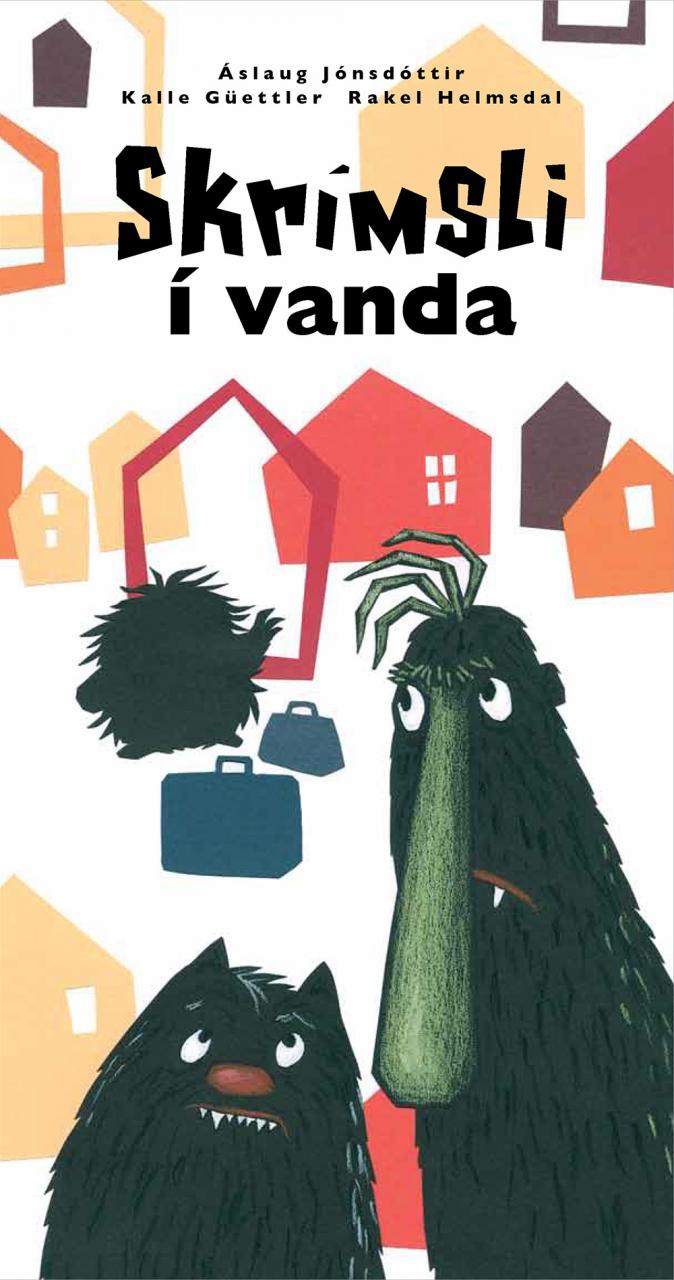

Áslaug has received numerous awards for her work. She is a two time winner of the Dimmalimm Prize (The Reykjavík City Illustrator's Award) and she won the West-Nordic Children's Literature Prize in 2002 together with Andri Snær Magnason for their book Sagan af bláa hnettinum (The Story of the Blue Planet), and she was awarded the Icelandic Literature Prize for best children's book in 2017 for Skrímsli í vanda (Monsters in Trouble).

Author photo: The Reykjavík Museum of Photography.

From the Author

From the Áslaug Jónsdóttir

Once upon a time, a long, long time ago … there was a farm, there was summer, there was a meadow, there was hay, there was a small hill, and there were people and a child with a rake. This must have been ages ago … sometime after the middle of the last century. The people sat on the hill and chatted about the good weather, they had put down their rakes and were watching the cut grass and the tractors running around it. The child with the rake had also walked the round and followed the hay that got left out. The child looked at this enormous green field. It took forever to walk around it. Endless rounds. But that wasn’t enough. Even bigger ones waited for the same treatment. Waving fields of green grass as far as the eye could see. Whole summers filled with raking hay. Many, many days of walking with the rake. The child dreaded growing up and having to rake these giant fields days on end. It was astonished by how happy the grown ups were about the whole thing. They laughed and talked about things that were not connected with their work. They talked about the Nobel poet. The Nobel poet said this and the Nobel poet wrote that. “What does a Nobel poet do?” asked the child. “Halldór [Laxness] is a writer, he writes books,” was the answer. “Easy as pie!” thought the child and ran its rake through the grass as it thought about a story and a picture of an elf that it had made very quickly earlier that day. “I will be a writer when I grow up,” the child said, “then I won’t have to work.”

Why were they laughing? I did not understand it then.

Now the fields look small and the grass as green on both sides of the stream. When I get to make hay, I am no longer overwhelmed by the work, even if the weather-gods can be tricky. When it comes to writing and creating books however, I see endless rows of words and pictures, a well of enchanting work that makes me forget about summer vacations, eight-hour workdays and a stable income. In this field, you can hardly trust in anyone but yourself, and I try to rake my little stack together.

There is no direct line from my first ideas about the work of a writer to the fact that I have created picture books for children. The path through life is windy and strange; one day time has brought you a title, experience and a resume, which says that this is who you are. Once, future was a giant space of possibilities. As far as I can remember, I meant to become a horticulturalist or a witch rather than a writer or something of that sort. Or maybe a lighthouse keeper, bird specialist, train conductor or a farmer. I didn’t become a farmer, but I still work at one of the fundamental trades. Artists have in common with farmers to make goods that we cannot live without and these goods then create a living for even more people.

I write texts because I draw. I draw for the same reasons other people write. Stories come to me and I look at life through pictures and words. I am enchanted by the complicated, or not so complicated, combination of arks of paper that seem to be able to contain everything between heaven and earth, that which we call a BOOK. I am a true admirer of the picture book and I feel that I have hardly begun to study its possibilities and its wonders. Without doubt, I can be said to be nostalgic when it comes to children’s books, but as everyone knows who read as a child, magic moments do exist. These are the moments I remember and it is the feeling of endlessness and freedom that I encounter in the world of the children’s book.

Áslaug Jónsdóttir, April 2006.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir: Áslaug Jónsdóttir and Saturated Images: or No! Said the Little Picture

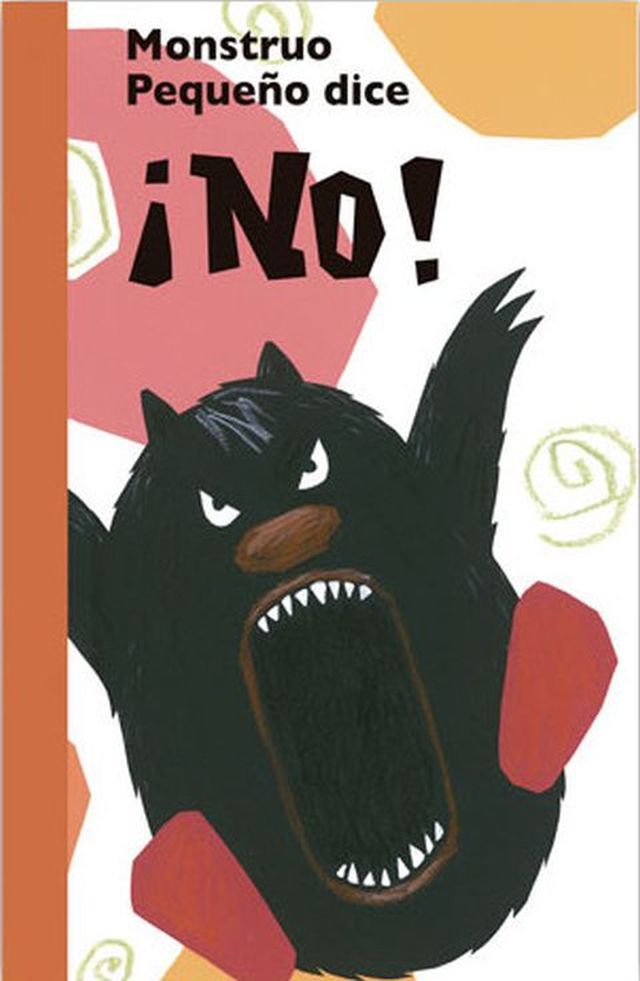

I can probably be accused of literary cuteness, but still I cannot resist turning the little monster in the tale by Áslaug Jónsdóttir, Rakel Helmsdal and Kalle Güettler into a symbol for the position of the image versus the word. This short little story tells us about the little monster that is sick and tired of the big monster’s continual dominance and finally brings itself to shout “No!”

“The image is syntactically and semantically dense in that no mark may be isolated as a unique, distinctive character (like a letter of an alphabet)” (184) says the literary theorist W.J.T. Mitchell in his discussion on pictures and paragraphs, referring to the theories of the philosopher Nelson Goodman. This is in a reference to the general discussion on the position of the image vs. the word, where the image is generally assumed to be weaker. Goodman, however, emphasises that the meaning of images is saturated, while the meaning of language is demarcated - it can be limited to a letter or a word, while the meaning of the image cannot easily be restricted to a particular colour or form, its symbolism is always inferred from the entire picture. Roland Barthes also discusses the inflated world of the image in his article “Rhetoric of the Image.” His theory is that this saturated meaning is continually tamed by the text, the written word, accompanying the picture and controlling its meaning. The articles “Pictures and Paragraphs” and the “Rhetoric of the Image” appeared in Icelandic translations in the magazine Ritið (1:2005), in an issue dedicated to words and pictures, their interaction and conflict. By looking over the contents the different forms of the discussion on words and pictures can quickly be grasped, here are articles on art theory, visual culture, sign language, semiotics and there is also a comic strip. Last but not least there is an article on illustrated children’s literature, the books about the kittens Snúður and Snælda, who, according to philosopher Gunnar Harðarson, found themselves in some gender confusion through translation. In the original French stories (by Pierre Probst) the kittens were both male, but in the Icelandic translation one of them is female. And Gunnar discusses this amusing gender bender in relation with the interaction between pictures and words.

It appears comical to see such a long theoretical article on such simple children’s books written by a philosopher in a respectable scholarly journal, published by the University of Iceland. However, on second thought, this theme of pictures and words would have looked silly if such an article would not have been included. The interaction of pictures and words is after all mainly pursued systematically in children’s books (of course this relationship is also pursued in ads). The comic strip is also important in this context, although it is a slightly different thing, as in the comic text and picture are much more closely tied together - it is not possible to say about a comic that the pictures are just illustrations, for example.

But is it really possible to say that pictures in children’s books are ‘just illustrations’? Not according to Áslaug Jónsdóttir, writer and illustrator, who prefers the word ‘illumination’ (the Icelandic word she uses, ‘myndlýsing’, is the same word as illumination, but literally it means ‘picture-description’, thus referring to the narrative and interpreting role of the picture accompanying the written text (however, as the English word illustration is more open for this role of the picture I will be using that word here)), to emphasise the importance of pictures in children’s books, an importance that goes far beyond being ‘only’ a decoration (the Icelandic word ‘myndskreyting’ literally means ‘picture-decoration’). This must of necessity reflect on the role of decorations: why they are always assumed to be such an unimportant and negative phenomenon, but this is a separate discussion for a completely different article. In 2001 Áslaug wrote an article for the magazine Börn og menning (Children and Culture), “Yfir eyðimörkina á merinni Myndlýsingu” (“Over the desert on the mare illumination”), where she discusses the position of illustrations in Iceland and raises, among other things, the question “Only for children?” Here one can recall the position of the comic book, which, while being originally intended for adults (appearing in newspapers) is continually assumed to be children’s material, all despite the fact that much of the subject matter of comics is far from being suitable for children. I must share with Áslaug the hope that some day illustrated books for adults will become as conventional as picture books for children. Perhaps this might serve a double purpose, to strengthen the position of the comic book and illustration in general. As yet, mainly illustrated books of poetry are being published, and in these cases the book is clearly portrayed as an art book (coffee-table) or as a collaboration between writer and artist, examples include Bernd Koberling’s watercolour-books with poets Baldur Óskarsson, Gyrðir Elíasson og Snorri Hjartarson and Eyðibýli, a book on the deserted farms of Iceland with photographs by Nökkvi Elíasson and poetry by Aðalsteinn Ásberg Sigurðsson, to take a few examples.

Áslaug Jónsdóttir has worked for a long time as a writer and illustrator, publishing her first book in 1990, Gullfjöðrin (Feather of Gold). She first became well known in 1999 when a book she illustrated, Sagan af bláa hnettinum (The Story of the Blue Planet) by Andri Snær Magnason, was awarded the Icelandic Literature Prize. This award was interesting for many reasons, partly due to the fact that this was the first time that a children’s book was awarded this coveted prize, but in the year before the weak status of the eligibility of children’s books for such a general book prize had been the subject of much debate. It was also noted that it was Andri Snær who was awarded, not he and Áslaug together, even though it was clear that her part in the story was considerable, as she designed the book (complete with the very special typography) as well as illustrating it. This example was a clear indication of the strong position of the word, as the written part was assumed to be separate - or separable - from the ‘just illustrations’, the prize was then in fact rewarded for the manuscript by Andri Snær, not the book itself, if we wish to take the role of illustrations the whole way. (See more about Sagan um bláa hnöttinn in my article on Andri Snær here on the website.)

Not that Áslaug cannot get her own prizes, most recently she was awarded the Dimmalimm prize, The Icelandic illustrating award, for her book Nei! sagði litla skrímslið (No! Said the Little Monster). Áslaug illustrates the book and writes it together with Rakel Helmsdal and Kalle Güettler and it was published in four languages. As already indicated the book describes conflict in the friendship between the little and the big monster, the little monster would really like to keep things nice and quiet and is shocked by the behaviour of the big monster, who is always belligerent, breaking and stealing - behaving, actually, exactly like the stereotypical monster! But all ends well, the No! of the little monster makes the big monster regret its ways and they become friends again, having fun as never before. Áslaug illustrates the book in the style she is best known for, emphasising simplicity. The pages are white and on this white background appear some kinds of cut-outs and shadows, mixed with drawings with the thick black outline, also with sharp edges, to go with the cut-out-style. Also a part of the text is drawn in the same style, such as the No! itself. The whole assembly is particularly successful and the book highly deserving of its award.

Áslaug’s first book was Gullfjöðrin, as already stated. The story is a kind of a fairy tale, as so many of the author’s stories, telling the story of a little yellow bird who finds a large feather of gold. He does not hesitate, and grabbing the feather in his beak takes off to search for the owner, it being no small matter to loose a whole feather. On his way he meets with various birds, which all reject the feather, until finally the desperately tired little bird finds the glorious bird of gold and puts the feather in its place. The story is told in two ways, first in pictures and then in words, or first in a saturated sign system and then a demarcated one, to use Goldman’s concepts already quoted. This is a fun way to tell the story, for most of the readers are liable to experience how the ‘demarcated’ story told at the end of the book is considerably different from the ‘saturated’ one, spun by themselves from the pictures. The pictures contain some of the characteristics of Áslaug’s style, a kind of a mixture of print and drawing. This creates the texture of cutouts and appears particularly lively on the page, in addition to the highly amusing facial expressions and movements of the birds, the little yellow bird with the feather in his arms being the main star.

Áslaug’s next book, Fjölleikasýning Ástu (Ásta’s Circus) (1991) is more traditional, both the story and pictures. The story is about little Ásta who decides to enliven a birthday party with a homemade circus-programme. Stjörnusiglingin - Ævintýri Friðmundar vitavarðar (Sailing to the Stars - The Adventures of Friðmundur the Lighthouse keeper) appeared the same year, and is more in the style of the fairy tale, telling the story of Friðmundur the lighthouse keeper who discovers one night that the stars are in a mess because one of the twins, Castor, has been suddenly thrown off course by a shooting star. So Friðmundur sails his boat into the sky and saves the day (or night, rather). The pictures are similar to the ones in Gullfjöðrin, with a watercolour base overlaid with cutouts and drawings.

Á bak við hús - Vísur Önnu (Behind the House - Anna’s Poem) appeared in 1993 and is in the cutout style, with this particular print-finish, creating a distinctive and a little mysterious atmosphere. The story is about little Anna, who enjoys baking mud cakes. We also meet with the various animals in the garden, a cat and a mouse, a spider and some snails, flies and beetles, and then of course a bird and a worm. The pictures are vivid and pretty and the finish is particularly suitable for the animals and vegetation. Anna clearly resembles the little prankster in Prakkarasaga (A Tale of a Prankster, written with Sigurborg Stefánsdóttir) (1996), a story with both pictures and sign language describing a little prankster’s and his father’s trip to town. The father certainly has his hands full! Here the cutout style is pursued exclusively, suiting the prankster’s bustle perfectly.

Áslaug returns to fairy tales again in Einu sinni var raunamæddur risi (Once There Was a Sad Giant) (1995) and Sex ævintýri (Six Fairy Tales) (1998). Áslaug herself describes the sad giant as a story about a giant without a sense of humour, who is searching for laughter. The animals quack or crow to him but there is no beast that can laugh, until he meets the children. The style of the drawings was later to become characteristic for Áslaug’s illustrations, simple drawings with thick outlines, giving the pictures a strange weight on the pages, as well as creating a texture of a kind of relief. The story of the sad giant is also somewhat reminiscent of Oscar Wilde’s story, The Selfish Giant. Áslaug illustrated a new Icelandic translation (Risinn eigingjarni) of this fairy tale in 2001. That story also tells of a giant and children, while being rather more dramatic than Áslaug’s story. The pictures are black and white as becomes the atmosphere, and her style of print, cutouts and drawings interacts well with the story, giving it a rich and gothic aura.

Colours and joy are, however, the ruling principle in Sex ævintýri, many of the fairy tales being allusions to well known tales. Here photo-cutouts are added to the mix, creating yet another variation, this is particularly successful in the story about the lazy cook, as seen in a picture where the young boy, who is not lazy and actually likes to cook, takes over the kitchen and is cutting chives among a feast of enticing foodstuffs.

In 2003 Áslaug’s story Eggið (The Egg) was published, a funny little fairy tale about an egg on the run. As before Áslaug uses colours to create an ambience, and here traditional children’s colours are noticeably absent, instead the colours are rather muted autumn-colours. The story describes how an egg falls out of a nest and into the lap of a cat. When the cat tries to grab it, the egg rolls away and into the most unlikely adventures. Áslaug also plays with language and uses all kinds of words containing ‘egg’, few of which translate well into English. The style of drawing (familiar from Sagan af bláa hnettinum) is in evidence, with the thick supple outlines that simultaneously appear still and powerful, mixed with the drawings is then the peculiar print finish and the cutouts, appearing mostly in the background and together this all creates an enjoyable story.

In her article already referred to Áslaug discusses the role and types of illustrations. She separates the role into three:

- decoration (designing a visual frame, making pictures)

- information (depicting the narrative, telling the story)

- explanation (interpreting ideas, deepening (a certain) understanding)

saying that the importance of the illustration is indicated by how many of these roles are in evidence. Types of picture books for children are five, according to Áslaug - provisionally. They are:

- A collection of pictures: Here there is hardly any text and the pictures interact due to a certain idea. Example: Books on the alphabet and suchlike.

- The storybook without text: Here a story is told in pictures, without text.

- The picture-and-storybook: Here pictures and written text are equal and the chain of events is interdependent.

- The illustrated book: Here the text can stand without pictures, while the pictures are important - interpretations of characters and events, for example.

- The toy book: Here are books with flaps and suchlike, sometimes rising up when the book is opened, Áslaug calls this a paper-sculpture and here, as before, content and design have to work together.

It is interesting to compare these roles and types with the different ways to make words and pictures interact in comic books, presented in seven categories by comic book writer Scott McCloud in his book Understanding Comics (1993):

- The word is dominant: Here the pictures are only decorations and add nothing to the text.

- The picture is dominant: Here the picture is the main carrier of meaning, the word is only a decoration, an exclamation or such like.

- Word and picture are equal: Here words and pictures say the same thing, the text tells us what we see on the picture, and vice verse.

- Word and picture add something to each other: Here the words add something to the pictures and vice verse.

- Word and picture are parallel: Here there are two (different) stories told, one in pictures and another in words.

- Word as picture: Here the words are a part of the picture, exclamations and such like appear with a particular lettering inside the picture but not separated in a word balloon.

- Words and pictures are interdependent: Here the importance of word and picture is equal, and neither may be left out if the meaning is to be clear.

It is obvious that there are some similarities in two types of categories, McCloud’s second category is similar to ‘the collection of pictures’ and ‘the storybook without text’ in Áslaug’s schema, her ‘picture-and-storybook’ would fit into either the fourth or the seve th category in McCloud’s system (they are in fact closely related), McCloud’s first and third category is the same as ‘the illustrated book’ in Áslaug’s schema and one might venture that the ‘toy-book’ is in some way similar to the sixth category, where words become a part of the picture. The three roles are also interesting in this context, as McCloud’s categories clearly align themselves to the importance of the three roles of the picture, decorations (first and third category), informations (second and fourth) and explanations (fourth and seventh). McCloud’s fifth category, where two stories are told parallel, I believe to be peculiar for the comic book, at least I have not seen this style used in such a way anywhere else.

Áslaug’s own books could also fit into these schemas, Gullfjöðrin is obviously a ’storybook without a text’, at least partly, and the picture-dominant category of McCloud, while her other books would be categorized as ‘information’ and ‘explanation’, or McCloud’s fourth and seventh category.

But what then about her illustrations in stories by other writers? Here the problem with Goodman’s dense or saturated meaning, as opposed to the demarcated meaning of the language, is evident, for this density or saturation is of course dependent on the reader’s training in reading pictures and the stress she or he places on the picture versus the word. In my view all three roles of illustration appear in Sagan af bláa hnettinum, and at least two of them in Wilde’s story of the giant, and thus I would judge the role of the pictures to be inseparable (McCloud’s seventh category) from the text. At first one might think that Áslaug’s illustrations to the story Ormurinn (Worm) (1998) by Kristín Steinsdóttir are mainly a decoration, but a closer look reveals that the role of the pictures is more extensive, for example we meet a new kind of worm in the form of a number for each chapter. Perhaps the illustrations to Krakkakvæði (Kid’s Poems) (2002) by Böðvar Guðmundsson could be most directly called a decoration, for they do not in general offer up much of an interpretation or explanation - still there are important exceptions, such as the book cover itself.

These reflections on where decoration starts or ends in comparison with the interplay of words and pictures in comic books must also call for a further exploration of the theories of words and pictures introduced in the beginning of the article. As a literary critic I have to be sceptical about all ideas of the ‘purity’ of language, its abilities for demarcations and denotations. I certainly agree with Goodman and Mitchell that the symbolic world of the picture is both dense and saturated, but I fail to see why the written word has to come so badly out of this comparison, as a narrow meaning, for text on a paper - for those who can read - most always demand a similar kind of a cohesion of meaning, even though it is certainly possible, if one is really anal, to isolate a single, easily recognizable item, such as a letter in an alphabet, such activity has hardly any purpose, generally speaking. In the same way I find it a bit restricting to see the text always in the role of the concrete immobilizing element, as in Barthes’s theory. In McClouds’s system it is assumed that the pictures can enrich the words, or that words can have a visual role, and I believe that the same applies to Áslaug Jónsdóttir’s illustrations. Just like in the comic book, where the picture is usually the dominant element - generally speaking - and the text is seldom in an overriding role; Áslaug’s texts are not at all the big monster in her books. On the contrary, it is the picture that captures the reader’s attention, and the pictures are the element that moulds and enriches the text, opening it up for various connotations and possibilities of meaning.

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, 2006

The quote from W.J.T. Mitchell is from Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press 1987 (1986), p. 67.

Articles

Criticism

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 450

Awards

2017 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Skrímsli í vanda (Monsters in Trouble)

2015 - The IBBY Honor List - Skrímslakisi (Monster's Kitty)

2008 - Gríma, the Icelandic Theatre Awards: Gott kvöld (Good Evening; the play) As the children''s play of the year

2006 - Reykjavík City Scholastic Prize: Stór skrímsli gráta ekki (Big Monsters Don‘t Cry)

2005 - Reykjavík City Scholastic Prize: Gott kvöld (Good Evening)

2005 - Dimmalimm, The Icelandic Illustrator´s Award: Gott kvöld (Good Evening)

2004 - Dimmalimm, The Icelandic Illustrator´s Award: Nei! sagði litla skrímslið (No! Said the Little Monster)

2004 - IBBY Honor List: For her illustrations in the book Krakkakvæði by Böðvar Guðmundsson

2002 - The West Nordic Children´s Book Prize: Sagan af bláa hnettinum (The Story of the Blue Planet). Together with Andri Snær Magnason

2002 - IBBY Honor List: For her illustrations in Sagan af Bláa hnettinum (The Story of the Blue Planet)

2000 - Reykjavík City Scholastic Prize: For her contribution to children´s books illustrations

1999 - The Library Fund for Authors

1993 - IBBY Iceland Award

Nominations

2021 - Fjöruverðlaunin - The Women's Literature Prize: Sjáðu!

2017 – The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award

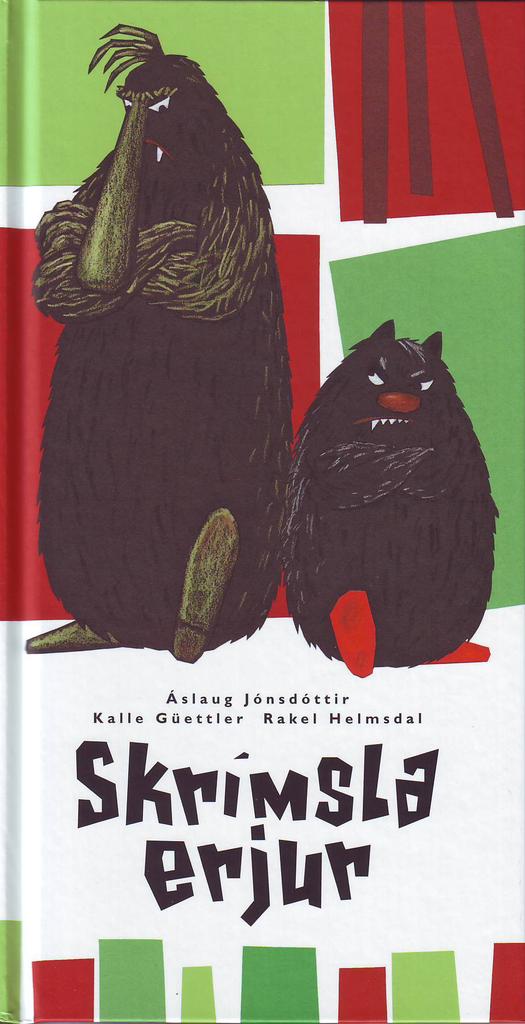

2013 – The Nordic Council‘s Children‘s Literature Prize: Skrímslaerjur (Fighting Monsters)

2010 – The Nordic Playwright Prize: Gott kvöld (Good Evening – a play Áslaug based upon her own book)

2006 - The Nordic Children´s Book Award (Nordisk börnebogspris): Gott kvöld (Good Evening)

1999 - H.C. Andersen Prize: For her children´s book illustrations

1999 - Reykjavík City Scholastic Prize: For her illustrations in Sagan af bláa hnettinum (The Story of the Blue Planet)

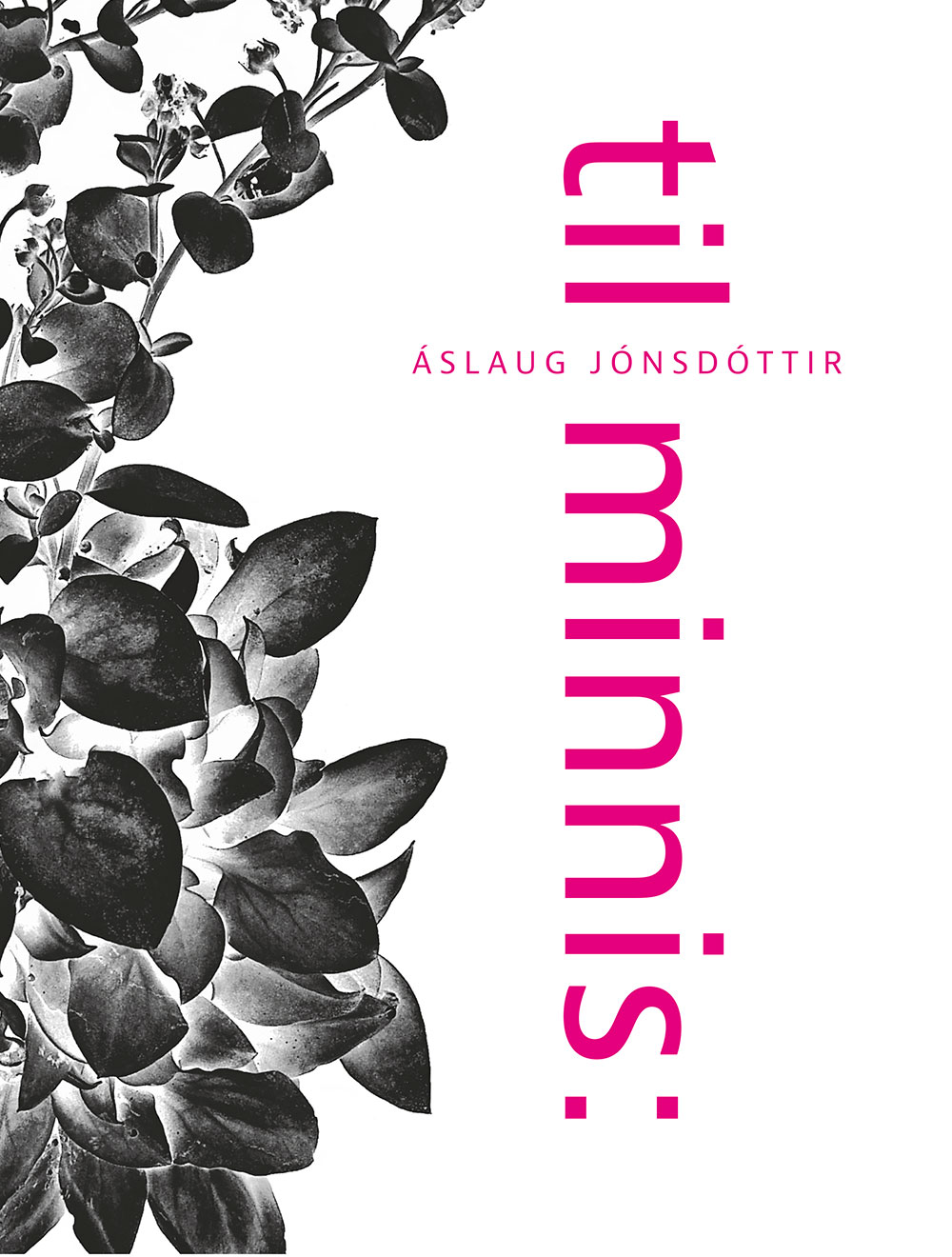

til minnis : (note to self :)

Read moreöldur rymja. með storminn í hálsinum. bryðja urð og grjót. uns lægir

Skrímsli í vanda (Monsters in Trouble)

Read more

Monstruo pequeño dice ¡no!

Read more

Skrimslaerjur (Fighting Monsters)

Read more

Grand monstre est jaloux

Read more

E! Sanoi pieni hirviö

Read more

Petit Monstre a peur du noir

Read more

Grand Monstre est malade

Read more

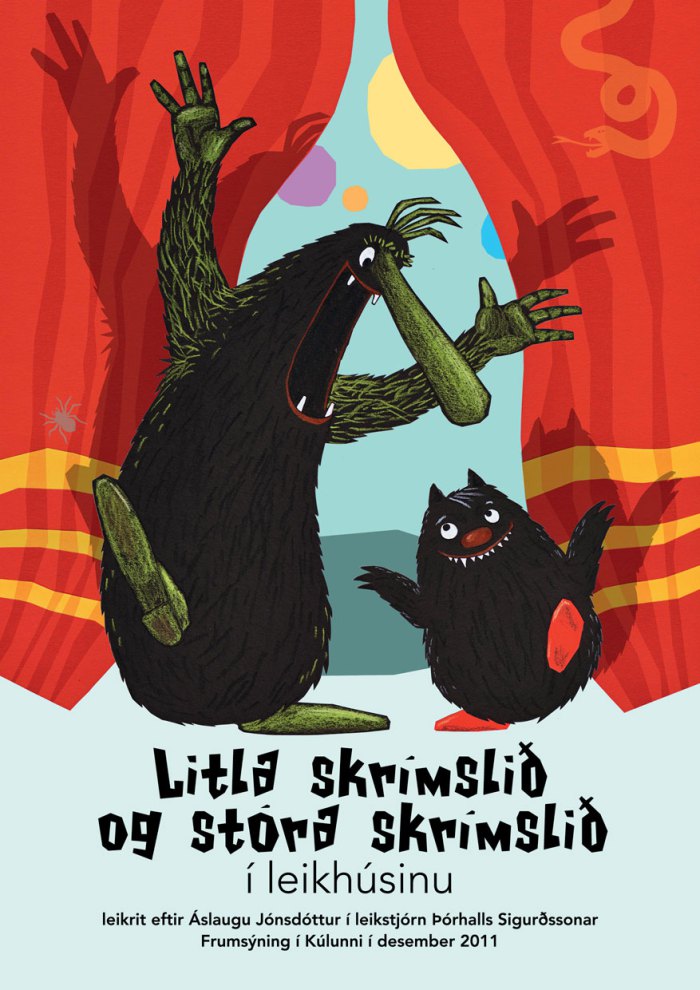

Litla skrímslið og stóra skrímslið í leikhúsinu (Little Monster and Big Monster in the Theater)

Read more