Bio

Birgitta Halldórsdóttir was born on June 20, 1959 at the farm Eldjárnsstaðir in Blöndudalur in North Iceland. She grew up at the farm Syðri-Löngumýri in the same region and attended school at Húnavellir and at Laugarvatn in South of Iceland. Birgitta has lived with her husband at the farm where she grew up since 1986, but they started out at the farm Leifsstaðir in Svartárdalur where he grew up.

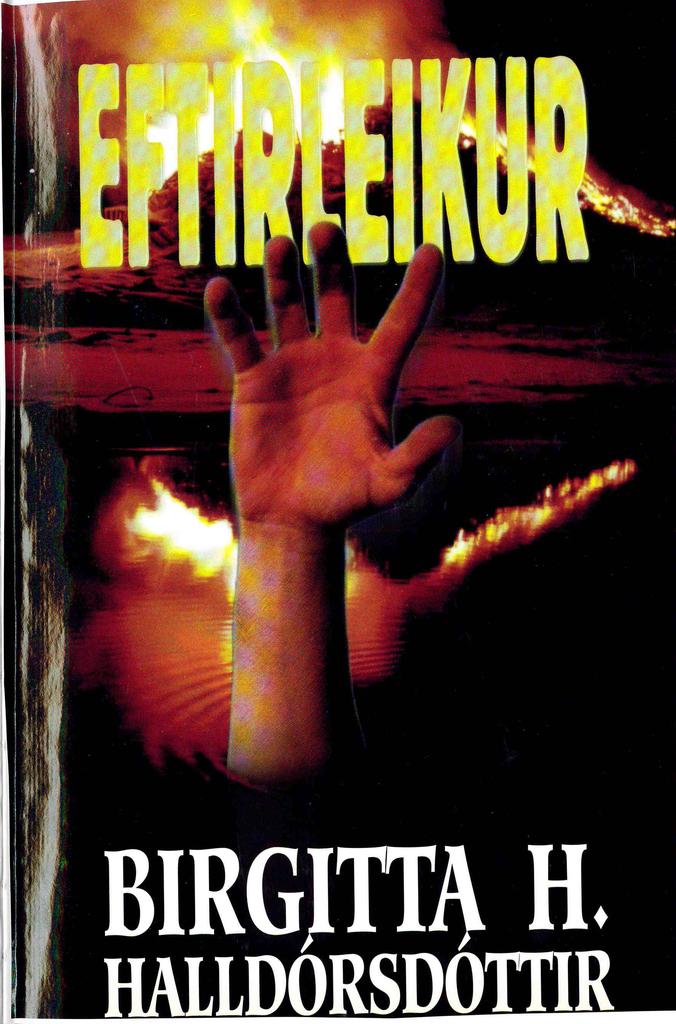

Birgitta has published many novels and interview books. Her first novel, Inga, appeared in 1983 and since then she has published sevaral more. Her stories, which contain a mixture of suspense and romance, have been very popular with Icelandic readers.

From the Author

Reflections on writing

Since I was a child and learnt to write I have had a strong urge to express myself in that medium and I feel that it is one of the best ways to give vent to pent up creativity, and to let the imagination roam free. As a child I bombarded my friends and relatives with letters of various quality, but later these writings developed into short stories, essays or poems, once I got a whiff of them at school. My need for writing is very strong, the need to express myself on paper. Yes, sometimes I get very bored with the computer and avoid it for a while, but sooner or later I will sit down with a head full of ideas that refuse to budge until I have committed them to paper.

I have been very lucky to have had my stories published, because I know the market for Icelandic popular literature is very small. I am not denigrating them when I say that my stories are popular literature, I know how relaxing it is to read a thrilling novel. I enjoy very much to write my stories and I hope others enjoy reading them. I have always wanted to write thrilling books that bring joy to people in their daily toil, stories that most of the time take place in Iceland and have a fast-paced plot. Whether I have succeeded in this is for others to judge.

It is not just thrillers that I have written. All my life I have been writing short stories and poetry. To begin with I only wrote poems when I was sad and they were full of melancholy, but later I worked my way out of that routine and now I only write poetry if I am happy and great things happen in my life. I want to include one of my poems here, a poem I sent half way across the world in my mind, while I waited to receive my little daughter, but she was born in Calcutta in India.

Ást til Barns

Ást berst yfir hálfan hnöttinn, til þín

ást sem næstum sprengir hjartað

og við bíðum og fáum ekkert að gert.

Lítið barn bíður

veit ekki hver framtiðin verður

finnur einungis ást

frá fjarlægum heimi.

Tíminn silast áfram

hjörtun slá af ást til þín.

Lítið barn kemur heim

tár blika á hvörmum.

Gleðitár.

Áfram berst ást yfir hálfan hnöttinn

til kvenna sem fóstruðu þig

og lands sem fæddi þig.

Við horfum í fallegu brúnu augun

og finnum til ástar sem nær út yfir allt.

Ást sem getur sigrað allan heiminn.

Við elskum þig litla barnið okkar.

Elskum börnin okkar sem gefið hafa lífinu gildi

og innihald.

elskum löndin og þjóðinrnar sem þið komuð frá.

Hjörtun eru full af ást.

Megi ást okkar áfram berast

vernda litlu foreldralausu börnin.

Megi ást heimsins vernda og næra

öll börn.

[Love to a child

Love is carried across half the globe, to you

love that almost rips the heart apart

and we wait and cannot do a thing.

A small child waits

does not know what the future holds

feels only love

from a faraway world.

Time drags by

hearts beat their love to you.

A small child comes home

tears well up.

Tears of joy.

Love keeps flowing across half the globe

to women who fostered you

and to a land that you were born to

We look into the beautiful brown eyes

and feel a love that covers everything.

Love that can conquer the whole world.

We love you, our little child.

Love our children that have given life content

and meaning,

love the countries and nations of your origin.

The hearts are full of love.

May our love be carried forward

to protect the small orphaned children.

May the love of the world protect and nourish

all children.]

It depends on what I am writing each time which need I am fulfilling. I also write about people, which is great fun. For the past few years I have done the cover interviews for the magazine Heima er best [Home Sweet Home] and that is highly enjoyable. You get to know different people that are interesting to meet and chat to. In my mind all people are interesting. We have so many stories. I have also written two biographies, one about Guðrún Óladóttir a master of Reiki, and the recent one about Valgarð Einarsson, a medium. This work was great fun, although they are both working with spiritual matters they struck me as being very different, but working with them was very instructive and pleasant. I knew Guðrún Óladóttir quite well before since I did study Reiki with her and therefore I knew her methods very well. I had not known Valgarð Einarsson before we started work on the book, so that was a completely different situation. They both work at helping people and I have had great pleasure in getting to know them.

As a child and a teenager I read a great deal, but lately I have had to pick my reading material carefully since my time is a limited resource. I get great pleasure from reading Icelandic books and I like to follow the works of our very good authors. Of course I have a great interest in the Icelandic thrillers and every Christmas I await eagerly the latest work of Arnaldur Indriðason, whom I like very much. The books of Árni Þórarinsson, Hrafn Jökulsson and Viktor Arnar Ingólfsson are also very good. I am very pleased with the latest developments in this genre; i.e. that more thriller writers are joining the Icelandic market, this is very much a good thing.

To write a thriller is in my mind a very enjoyable and challenging task. To draw the outlines of a good plot, build it up and end with tying up all the loose ends is one of the most enjoyable things I do. Some of the stories will have a more difficult birth than others. Sometimes I am on the verge of giving up, but there is always something driving me on, a new idea and in the end I always start a new story.

I am a member of "The Icelandic Crime Society" which was formed to encourage the growth of the thriller genre in Iceland. It is both a fun and useful society. The society was offered a publishing deal early in January 2000, the authors in it wrote a crime novel together and it fell upon me to write one of the chapters. The book is called Leyndardómar Reykjavíkur 2000 [The Reykjavik 2000 Mystery] and is a story written as a serial where one author begins the story and the next chapter is written by someone else and so on until the mystery is solved. This was a lovely project and great fun to work on.

The narrator is a man and I especially enjoyed for the first time to write a first person narrative as a man. This proved [to me] what great things are possible with the collaboration of many people.

I have written nineteen thrillers and some might think that more than enough. But I am not through yet and expect to keep going while I still feel the urge within me. I want to encourage people to write if they feel the need for it. We all need to have an outlet for our creativity in order to feel good and stay balanced. We have many ways to express ourselves and should use the ones that suit each and every one of us the best. I am grateful for having the opportunity to get my material out there and I hope that books and printed material will continue to take pride of place as it still does with us Icelanders. Finally I would like to end on a religious note with this poem.

Ljósið þitt

Þráirðu ljósið?

Að lifa lífinu í hinu

ómeðvitaða sjálfi

og undrast uppruna sinn

og Guð.

Að leita fullnægju í

efnislegum allsnægtum,

óútskýranlegum tilfinningum

til samsömunar

annarri persónu.

Hver þekkir ekki efnið

undarlegt tilfinningaflóð

og ótal spurningar.

Ó, þú leitandi sál, líttu nær.

Innra með þér er almættið

að störfum.

Innra með þér er hið

guðlega sjálf.

Innra með þér er allt

sem þú þráir,

þú ert guð og guð ert þú.

Í öllu formi býr guðlegur neisti

guðlegt afl og guðlegur vilji.

Undrast ekki

þetta er ljósið.

Ljósið þitt.

Í hjarta þér finnurðu guð

finnur frið og fullnægju.

Horfðu í augu þín og sjá

þar er guð.

Guð í þér og þú í guði.

Órjúfanleg heild

sem ekkert fær aðskilið

og einginn dauði er til,

einungis sannleikur þinn.

Ó hve lífið er gott og hver

stund er dásamleg í guði.

Guð er ljós, friður og kærleikur.

Guð er ALLT.

Guð er ljósið,

ljósið þitt.

[Your light.

Do you yearn for the light?

To live in the

unconscious self

and to wonder where one comes from

and God.

To look for satisfaction in

a materialistic plethora,

unexplainable feelings

towards the union

with another person.

Who does not recognise the material

strange overwhelming emotions

and endless questions.

Oh, searching soul, look closer.

Within you is the almighty

at work.

Within you is

the divine self.

Within you is everything

that you yearn for,

you are god and god is you.

In every form there is a divine spark

divine power and divine will.

Do not wonder

this is the light.

Your light.

In your heart you will find god

find peace and satisfaction.

Look into your eyes and behold

there is god.

God in you and you in god.

Inseparable wholeness

which nothing can take asunder

and there is no death,

only your truth.

O, how life is good and each

moment glorious in god.

God is light, peace and love.

God is EVERYTHING.

God is the light,

the light is yours.]

Birgitta H. Halldórsdóttir, 2001.

Translated by Dagur Gunnarsson

About the Author

Heroines in Distress

Shortly before the turn of the century I was visiting one of the biggest and most respected bookstores of London, Dillon´s. While there, I searched desperately for Tania Modleski´s book, Loving with a Vengeance (1982), an analysis of romance and suspense fiction by women. I searched without results in the department of literary theory, gender studies, cultural studies and finally in the media and film shelves, although I knew it would not be found there. In my desperation I gave myself up to the thoroughly lazy staff of Dillon´s and asked about the book. Yes, we have it said somebody unusually energetic and marched over to the literary theory shelf. It is not there I said firmly, he turned to the gender studies where I also stopped him. In the middle of this circling around shelves another (unusually energetic) member of staff calls us back, having gone to the trouble of actually checking the computer. It is not on this floor he announced happily, it is on the next floor in the shelf for creative writing. What, I said, and what said the other staff person, yes see and the computerised one came scampering with the book. This is not shelved right! I said scandalised (once a librarian, always a librarian) but by this time they had both lost interest. Are you going to buy the book?

Because I am also a cultural studies researcher I could not but interpret this as an excellent example of the attitude that women´s popular fiction continually has to deal with. Modleski´s book is a theoretical analysis and feministic interpretation of romances and suspense fiction by women, and the culture surrounding it, but is not ´good´ enough to be shelved with other theory and thus finds itself shelved beside creative writing and other DIY booksgenerally perceived to be of a lower standard than theoretical works. Modleski emphasises how these stories have generally been considered to be conservative, but points out how they can often offer their readers a variety of possibilities of reading experiences, possibilities that often involve reading against the formula or finding in it elements that the women (the readership is mainly female) can experience as challenging. Modleski´s work was among the first of this kind and paved the way for further writings on discussion and writings on women´s popular culture, whether romances, suspense stories, soap operas or romantic comedies.

Birgitta H. Halldórsdóttir novels are written in a formal language, with traditional style and structure and follow the predetermined and familiar formulas of popular fiction. This is not said to put down her stories, for the sincere and nonexperimental approach to the form that she uses is no less important to the popular novel than the ironic postmodern take. Birgitta writes her novels of love and suspense into a certain tradition of such stories in Iceland, the country romances by Guðrún frá Lundi and Ingibjörg Sigurðardóttir and later Snjólaug Bragadóttir. The main differences is that Birgitta adds to the romantic formula strong elements of crime and suspense fiction and thus her books can be categorised as both romances and thrillers. Within this frame her books fall into most groups of love- and suspense stories. Some of the novels are closer to the traditional romance, like Inga [Inga] (1983) and Í greipum elds og ótta [Captive by Fire and Fear] (1986), some are closer to the crime novel like Örlagadansinn [Dance of Destiny] (1993), Áttunda fórnarlambið [The Eight Victim] (1987) and Sekur flýr þó enginn elti [The Guilty Runs though none is Pursuing] (1989) and some are reminiscent of the gothic romances such as Bak við þögla brosið [Behind the Silent Smile] (1994), Fótspor hins illa [Footsteps of Evil] (2000) and Dagar hefndarinnar [Days of Revenge] (1988).

Birgitta´s first novel, Inga, is more related to the traditional love story than the suspense story, even though the plot involves a crime. The story is about a young girl in a fishing village and her relationship with men. She has a relationship with Geiri, a young fisherman from the village but is not completely happy and dreams of adventures. She finds them in Hallur, a young and handsome man from Reykjavík whom she moves in with, but he proves to be a wolf in sheep´s clothing and treats her badly. She escapes to Geiri but Hallur follows her and attacks her. She is saved and now Hallur seems to be out of the story, but then he is found murdered and Geiri is blamed. When Inga starts investigating, she finds out to her own peril that it is the insane mother of Hallur who is the killer: and she poisons Inga as well. At the hospital she meets a young doctor and takes immediately to him and before we can blink an eye, they are married and the thirst for adventure is quenched.

In the next novel, Háski á Hveravöllum [Danger at Hveravellir] (1984), the crime plot has expanded. The story is about a young journalist who is sent to Hveravellir to investigate a suspicious death of her colleague. She stays in an isolated cabin with a few others who are also linked to the death of the woman, has a love affair, is persecuted by the murderer and her ex-boyfriend (possibly the one and the same) and finally solves the case. The third novel, Gættu þín Helga [Watch out Helga] (1985), takes place at a hostel in the country where a young girl arrives for recovery after a serious car crash. She has a broken leg, scars in her face and a broken heart after her boyfriend rejected her because of her damaged looks. At the same time the hostel fills with people, guests of all kinds; a elderly couple who is there for a rest, artistic sister and brother looking for a quiet place to work, a wealthy couple searching for a change, and in addition a young single man who does not seem to have any particular motif for his stay. When Helga´s boyfriend suddenly appears and demands to have her love back, it becomes clear that something is about to happen and suddenly Helga has been kidnapped along with the wealthy wife. Despite her injury Helga manages to find a way to escape the kidnappers, saving the woman.

In these three novels all the main characteristics of Birgitta´s stories are apparent. She often uses an isolated area as a scenea house in the country or a small villagethe heroine is a young, independent and often sexually active girl who is before long taken with one of the malesoften despite suspecting that he might be dodgyand the solution of the crime is usually found within a closed group, the criminal is someone close, even a member of the family. Even though at first the danger is directed towards somebody else than the girl, she is sooner or later personally involved with events and as a true modern woman is good at saving herself and possibly others. This is a fairly important part of Birgitta´s novels and is reminiscent of Carol J. Clover´s famous analysis of horror films for teenagers and the role of the heroine. For even though Birgitta´s stories are mostly related to love- and suspense fiction, they also bear some marks of the horror story. Her novel, Fótspor hins illa, is a case in point. In this story an Iceland girl who is raised in England is suddenly called home when her sister is found killed. Soon enough suspicious events start piling up in Iceland, and this peaceful country proves full of danger: it transpires that the sister was the victim of a group of satanists and our heroine is intended for a special role in their rituals.

According to Clover, the teen-horror film has changed the traditional role of the heroine in a radical way, and this change has had influence outside the genre. Clover points out that the traditional role of the heroine as a victim saved by a male hero has been turned around in the teen-horror films of the seventies and eighties, and instead of waiting to be rescued, the girl manages well on her own and thus takes on a double role of victim and hero, and these two roles become one. This analysis fits Birgitta´s novels well, as they are characterised by curious, determined and independent heroines, who do not hesitate to take on criminal investigations and are well able to get themselves out of the predicaments created by their own curiosity and investigation games. What separates Birgitta´s heroines from the heroines of the teen-horror film is that they are very sexually active. While the heroines of the horror film are usually virgins or sexually repressed in some way, the girls in Birgitta´s stories are generally quite virile, and sex and men play a large part in their life. They have lively sex with the men they fall forand even othersand often take the first step in such affairs. Furthermore they are completely uninhibited when choosing a man. Looks matter greatly and they ogle the men the want, watching their bodies, evaluating their masculinity and sexual attraction. In Myrkraverk í miðbænum [Dark Deeds Down-Town] (1990) it says: "I could not stop staring at his body. There was not an ounce of fat to be seen and all the muscles were in the right places. He was desirable and that is putting it mildly" (57). In this way Birgitta´s novels are also interesting in the light of feminist ideas about romances being a kind of ´porn´ for women; that women seek to read romances and enjoy them in the same way men seek pornography.

Perhaps following upon this, the threat that the heroines face is often sexual and this is another symptom that Birgitta´s novels share with horror fiction. Sexual threats, particularly from somebody close, is also characteristic of the gothic novel and the gothic romance discussed by Modleski in her aforementioned book. In the gothic novel, it is a standard that each family has at least one skeleton in a cupboard (this is actually almost taken literally in Birgitta´s novel Bak við þögla brosið), and that the young heroine is an innocent victim of events from the past.

The isolation is another hallmark of the gothic novel and romance that Birgitta puts to good use. Examples of novels that are mainly characterised by isolation are Ofsótt [Persecuted] (1996), Eftirleikur [The Game After] (1999) and Klækir kamelljónsins [Tricks of the Chameleon] (1991). Ofsótt takes place in Skagafjörður, where evil men lurk and it becomes clear that old wounds do not heal well. By using the Icelandic notoriously bad weather and the isolation of the farm, Birgitta creates solid tension and even moments of horror: the solution is to be found complicated family affairs of the past.

Birgitta´s stories also often have certain supernatural threads. Thus it is common that omens of all kinds appear in her novels, taking the form of dreams, second sight, prophecies or superstition. The heroine of Andlit öfundar [Face of Envy] (1995) has second sight, and the prophetical gift of Sara in Myrkraverk í miðbænum involves writing poetry that comes true. In this way Birgitta creates connections to both the Icelandic folktale tradition and the Saga tradition, as her omens hint at things to come in similar manner to these stories, and thus it is indicated that many things will turn out differently than intended. In this way what seems at first to be a rather innocuous narrative is propelled forward by arousing the readers expectations for exiting events.

These gothic elements are not present in all the stories, even though they are common. Some of the stories are pure suspense- or crime stories, focusing mainly on the crimes of the city. An example of this is Renus í hjarta [Renus at Heart] (1998), it is a pure thriller, containing international criminals, written in an effortless way into the traditional form of the popular novel, while obviously also containing a love story and strikingly handsome men and women.

Birgitta has written two novels taking place in the past, Dætur regnbogans [Daughters of the Rainbow] (1992) and Nótt á mánaslóð [Night in Moonlight] (1997). Dætur regnbogans describes the life and loves of a young girl who marries a much older man, and then falls in love with a younger one, and Nótt á mánaslóð is a story about witches. She has also written the biography of healer Guðrún Óladóttir. Furthermore she has a highly enjoyable chapter in the serial crime story Leyndardómar Reykjavíkur 2000 [The Reykjavík 2000 Mystery].

In cultural history popular culture and mass culture has been closely aligned with the feminine, and this alignment has generally been seen in as degrading for both. These connections between women and popular culture can be traced back to the history of the novel, the late eighteenth century and the nineteenth century novel generally being seen as a women´s form and a form of popular culture. Tania Modleski points out that the attitude towards mass culture is closely interwoven with our ideas about the feminine and thus claims that it is important to examine mass culture in relation to feminist ideas and theories. From the beginning, says Modleski, the woman has been central to history´s discussion on mass culture, and usually condemned, for example by the American author Nathaniel Hawthorne in the nineteenth century, who criticised the novels of his time for being produced by ´mobs of scribbling women´. This complaint of Hawthorne calls to mind the discussion on ´old wife´s´ tales´, taking place here in Iceland in the sixties, where female imagery was used to describe and condemn popular writings by both women and men. In this way the woman was made responsible for the degradation of good taste, ´sentimentalising´ culture, flattening and diluting it.

The majority of the novels from the latter part of the eighteenth century are so called novels of sensibility and it is this form that was tagged as popular form and at times merged with the gothic novel. The gothic movement has its roots in the mid seventeenth century, reaching its peak in the last decade of the eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth century, much like romanticism. The gothic novel quickly became a strong venue for women writers and readers, and was condemned for encouraging the consumption of mass culture, causing damage to its readers. When reading and literacy became more general it was related to autonomy, and parallel with the emphasis on reading as an individualist choice and activity, influencing the reader, a distinct disbelief in the readers ability to treat this right properly emerged, together with a discussion on the potentially damaging effects of reading. In particular, women and the lower classes were prone to harm.

The novel was the genre of literature that appealed mostly to the growing group of literate working and middle class, particularly women, who, following upon the rising prestige of the middle class, were to an increasing extent cooped up in their homes, excluded from any kind of work. The history of the novel in the eighteenth century is thus closely knit with women, as women were important for the development of the novel, despite being seldom seen on lists of the literary giants of the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth century women novelist become more evident, when writers such as Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters appear, writers that are now acknowledged by the literary canon, even though their stories are related to more frivolous stuff, such as the gothic novel and the novel of sensibility. And again, in twentieth century modernism, woman is made to stand as a symbol for mass culture in a negative sense, as seen in T.S. Eliot´s famous poem on the wasteland. In modern times we see this connection perhaps most clearly in the discussion on the status of the female body as merchandise and the passive object of the gaze in visual material from advertisement to films.

As I already said, Birgitta writes her novels into a tradition of Icelandic popular writings that were condemned in the sixties as ´old wives´ tales´, and as indicated this kind of an imagery is rooted in Anglo-American cultural history. Birgitta´s novels are also clearly related to Anglo-American romances, such as the gothic romances of Phyllis A. Whitney and the suspense- and love stories of Mary Higgins Clark. Despite a mostly lukewarmsometimes hostilereception by critics, Birgitta has continued to write a book every year and thus has till recently been our main and practically only representative of the tradition of crime- and love stories, having for years more or less single-handedly upheld the flag of Icelandic popular culture.

© úlfhildur dagsdóttir

Articles

Criticism

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 458

Út við svala sjávarströnd (By the Cold Seacost)

Read more

Þar sem hjartað slær (Where the heart beats)

Read more

Óþekkta konan (Jane Doe)

Read more

Tafl fyrir fjóra (Chess for Four)

Read more

Játning (Confession)

Read more

Ljósið að handan (Light from Beyond)

Read more

Fótspor hins illa (Footsteps of Evil)

Read more

Leyndardómar Reykjavíkur 2000 (The mysterys of Reykjavik in 2000)

Read more

Eftirleikur (Follow Up)

Read more