Bio

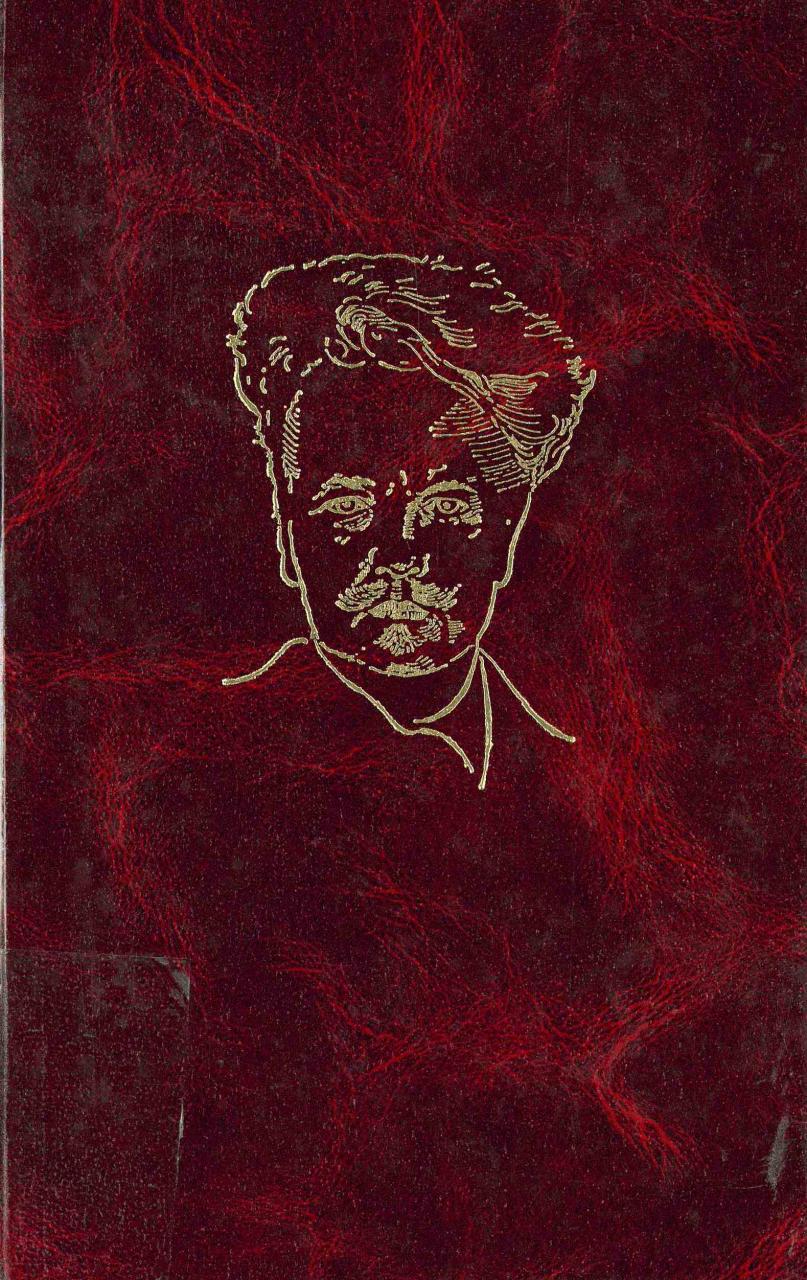

Einar Bragi was born in Eskifjörður, east Iceland, on April 7, 1921. He was brought up in Eskifjörður and after completing school in Akureyri, north Iceland, in 1944, he studied literature, history of art and history of drama at the University of Lund, Sweden, from 1945-47 and the University of Stockholm from 1950-53.

He worked in herring factories in north and northeast Iceland, as a tourist guide in other countries, a journalist on Þjóðviljinn newspaper and, intermittently, as a teacher of Icelandic in various schools from 1944-87. His many positions of responsibility for the literary community include serving as chairman of the Icelandic Writers' Union 1968-70, chairman of the Icelandic Writers' Fund 1974, Iceland's representative on the Nordic Council of Ministers' Committee which compiled the rules for the Nordic Translation Fund 1972-74, and the Federation of Icelandic Artists' representative on the board of the Nordic House for many years. He founded the literary magazine Birtingur in 1953 and was on its board until it ceased publication in 1968.

Einar Bragi's first volumes of poetry, Eitt kvöld í júní (One Evening in June, 1950) and Svanur á báru (Swan on a Wave, 1952) were published while he was living in Sweden, and his third after he returned to Iceland in 1953. Since then he has published numerous books of poetry, novels, memoirs and collections of essays, as well as being a prolific translator of poetry and prose into Icelandic. Among his translations are the plays of August Strindberg and Henrik Ibsen.

Books of Einar Bragi's poetry have been published in several translations and individual poems have been anthologized in many languages.

Einar Bragi passed away in Reykjavík in March 2005.

From the Author

From Einar Bragi

Einar Bragi was born in Eskifjörður (east Iceland) just after the end of the First World War and was 18 years old when the second started. The Icelandic nation barely had time to bring him to manhood before peace came to an end, although it is unlikely that the Second World War was directly his fault.

His mother's side of the family is thought to be purely Icelandic but his paternal lineage has been mixed with Swedish blood and Danish and even Norwegian, shameful as that may be to admit, but there might be some mitigation in the fact that his father had a jet black beard and hair and was conceived in Djúpivogur, which separately and in particular in combination could indicate more southerly genes centuries back.

Eskifjörður was a fairly quick-fried village: with 53 inhabitants in 1874 who had grown twelvefold half a century later ? in terms of numbers, that is. The growth rate can be attributed to the beginning of the herring fishery around 1880 and of the age of motor boats in 1905. His father was a fisherman and rarely at home, while his mother handled the children's upbringing and ran the home in a high and mighty fashion, despite her short stature. She lay in childbirth five times and no one thought that a great feat apart from her; her mother, who was even shorter and extremely petite, had nine children. He sometimes used to wonder where those little women had kept all those fourteen children, some of which were no small fry, for example he weighed 10 pounds himself at birth. When he put these reflections to his mother she answered: Well, we didn't carry you all at once!

His sweet childhood memories include the times in the shoreside part of the village, Framkaupstaður, when a blizzard raged outside and his mother stoked the coal stove to glowing, opened the stokehole and put out the light, then lay down on the kitchen floor with her children, two on either side, and they all stared into the red embers as she told them about when she was a little girl and lived at Lón or Fagridalur in Vopnafjörður or at Kolbeinstangi.

Just behind the house in Framkaupstaður was a pond called the Ice-House Pond where Einar Bragi practised the sport of skating early in life although his prowess in the field is not mentioned in any chronicles. This was later supplanted by skiing trips which could become very long when temptations tugged him ledge after ledge all the way up into Lambeyrardalur, where Mt. Andri guarded the entrance to the valley on one side while on the other were the haunts of outlaws where the women they had kidnapped and were holding captive could be heard howling. But his idol among sportsmen was Jón Ben the dentist, who went to Eskifjörður once a year and spent several days there making false teeth for people who had been given a voucher for a set as a birthday or confirmation present. At lunchtime Jón would take a break from making dentures, strip off his clothes, throw a bathrobe around himself, walk slowly and solemnly down to the Outer Quay, take off his bathrobe and dive without flinching from the end of the jetty, head-first into the cold sea. Einar Bragi considered this a valiant deed and promised himself he would do the same when he was big. And kept his word. As a teenager he was taught to swim by Friðrik Jezson in the Westman Islands and could hardly be kept on dry land at first afterwards. Two worthy citizens who were little boys in Eskifjörður at the time say they clearly remember staring wide-eyed at him dive from the end of Framkaupstaður quay, and many a sports hero has had to accept having fewer spectators when performing greater feats.

At the age of eleven Einar Bragi first went away from home to spend the summer at Borgarhöfn in Suðursveit (southeast Iceland). Haymaking technology then was on the same level as it had been in the days of Egill Skallagrímsson, apart from the fact that Þorsteinn the carpenter from Steig in Mýrdalur had introduced sockets to replace the straps previously used to hold the scythe blades in place, and Árni Eylands the Scottish scythes that were named after him. At Borgarhöfn, everything that could be used was used. Considerable quantities of fishing net bobbins were often washed up on the shore, woven together with twine. On indoor days when downpours of rain prevented people from going to the meadows, Einar Bragi and a girl named Ásta were given the task of untying the bobbins, around 40 knots on each one. Then the twine was wound up into convenient-sized hanks from which ropes were braided in winter. These hanks led him to recall a phenomenon he had often seen on the seabed when he was dredging for flatfish on the mudflats at the head of the fjord back home. These were tiny sand hills or mounds, curved like a slice from a handball, with a texture like an unravelled two-pound line. Someone had told him these were the dwarf type of a species of worm which imbibed nutrients from the sand and then left it in such a tidy loop. Perhaps that is where the idea for the title came from: Braiding a rope from sand. After he became a writer of verse he felt a certain affinity with that remarkable sea creature: poets spend a lifetime as (poe)tasters of life's Long Sand, curling up into miniature sculptures which they deposit on the beach after they leave and are called poems.

I'll be damned if there isn't a dash of sun on Pleatsack's Edge; I suppose the weather'll start clearing up, said Ásta.

Why's it called Pleatsack's Edge? he asked.

Can't you see that the cliff on the face of Mt. Borgarhöfn looks just like a pleatsack? she replied.

What's a pleatsack?

I'm astonished, said Ásta, doesn't the fishing village boy know that a pleatsack is the stripy coat of blubber on a whale's belly?

I've never seen a whale, he answered: the Norwegians had killed all the whales in east Iceland before I was born and they turned all the pleatsacks into oil, then sailed to Africa to kill whales there but left the stations to rust and rot where they were.

We have a place called Veil Hill around here too, Ásta said wryly to tease him, it's in the east in Mörk and you can't see it from here. There was a farmer called Árni from Sævarhólar who didn't have any children with his wife but had seven in secret with his serving-woman and threw them all over the edge of Veil Hill. That's where the poem comes from:

Some never find a grave to fill:

but under the snowy cowl

below the edge of old Veil Hill

the swaddling children howl.

You're making me feel afraid of the dark in the middle of the day, he said.

Sorry, she said. But do you know why you must never say: 'Sorry it's only a trifling thing', when someone thanks you for a gift?

No, I don't.

Then she told him a story:

Once upon a time long ago the Bishop of Skálholt was making a visitation of east Iceland and had taken his wife along for her pleasure. One evening they camped close to the vicarage at Kálfafell in Fellshverfi. Before the bishop and his wife went to bed, they took a stroll along the plain, because the weather was calm on land and at sea and there was a cheerful view of the glaciers. They encountered a woman from the farm Brunnar, who was carrying a blanket that she said she wanted to give to the bishop's wife as a souvenir of her visit to Suðursveit.

The lady unfolded the blanket and looked at it admiringly, praising the craftsmanship, and thanked her kindly for this noble gesture.

Sorry it's only a trifling thing, the woman replied.

I call that a treasure and not a trifle, said the bishop's wife, and I don't believe such a blanket was spun in a single day.

It was on the loom for twelve years, the woman replied, and not only because of my tardiness. The weft is spun from my hair, and it wouldn't grow faster than the Almighty allowed.

Einar Bragi was none the wiser, but ever since these heartfelt conversations took place he has been wrestling with peculiar words such as Pleatsack Edge, mysterious verses and strange stories akin to those that Ásta told him long ago, or struggling to untie if only a single knot in the intricate net that someone wound long ago around the bobbin of this Earth.

Einar Bragi, 2001

Translated by Bernard Scudder

About the Author

Pride of place for poetry: On the poetry and writing of Einar Bragi

Einar Bragi's first poetry was published in school magazines when he was a student at Akureyri Secondary Grammar School. This would have been around 1940 or just afterwards, when the author was roughly twenty. During his school years Einar Bragi spent many summers working in the herring factory in Raufarhöfn, where texts and prose poems by him appeared in the notice-board publication The Factory Worker. Poems by Einar Bragi began to appear in magazines in 1948 along with lyrical texts that testify to this close acquaintance with working life and his upbringing in a coastal village. "Scenes from a Factory Village" is the title of a lyrical cycle of poems which was published in the fishermen's journal Víkingur in 1948 but might have originated from The Factory Worker. The series "The Wandering Jew. Street Scenes", printed in the journal Work the same year, might also be traced back to there. It is the "ordinary street of the ordinary man" that supplies the setting for these texts, as the author says: a man, a woman, a child, happiness and toil. The poet then elevates these themes from ordinary life and work to a new plane of existence in his first book of verse, One Evening in June (Eitt kvöld í júní), in 1950. There they are reborn in lyrical sophistication, often adorned with alliteration although all the poems are unrhymed.

Einar Bragi's roots in the everyday toil of ordinary people before the days of the technological revolution leave their imprint on his work from the very start. He has given a realistic account of his own childhood and people's lives in Eskifjörður in his memoirs Of Man Thou Art (Af mönnum ertu kominn, 1985). In his poetry, he gives a more gentle treatment to his childhood haunts and his contemporaries, yet beneath the lyrical and sometimes melancholic surface dwells an objective appraisal of abject poverty and the tough struggle for sheer survival. This can be seen in "Home", the opening stanza of which, printed in Einar Bragi's debut volume of poetry, is as follows:

Charged with love through

memories'

mist it shines,

upon the impoverished, the harsh

hunger bay,

my home ground.

The poem then appeared fully formed in three stanzas in his next book, Swan on a Wave (Svanur á báru, 1952), with the final stanza:

Good world

give back to me

my golden hoard:

my life's lost

light spring

I look for you.

Such homesickness may have a romantic ring to it; emotions are never excluded from Einar Bragi's poetry, but his "hunger bay" enshrines a realistic appraisal of his childhood haunts. Einar Bragi's poetry is all lyrical in the best sense of the word and consequently his style often has a romantic air about it, yet the mentality of the poems is shaped by the age he lives in and the struggle against injustice and for a better life.

Swan on a Wave contains one of Einar Bragi's best-known poems, originally titled "Autumn Poem in Spring 1951". He later omitted the year from the title and changed the poem somewhat. It is written in opposition to the arrival of US military forces to be stationed in Iceland in spring 1951 and delivers an impetuous protest beneath its lyrical exterior. The last stanza runs:

Scared and silent as the trees

is my nation so young,

you too are shaken the same:

you sing no longer,

the breeze bears from beyond the seas

an autumn poem in spring.

What causes that sorrow so grave,

O swan on the wave?

This poem is sharply at odds with the tradition of political rallying-calls with their bombast and war-cries, for which there is a long history in Icelandic verse. And as it turned out the poet was rebuked for this poem by political tub-thumpers, not least those who shared his views. While they decried it for lacking scathing language and militancy, this poem has survived longest and best of the myriad composed on the same occasion. Here the barb lies in the nature imagery, for nature can be a mirror of social issues and all misdeeds against the nation are detrimental to the land too.

The revolution in form

Einar Bragi's first books of poetry clearly reflect the great conflicts that were going on in Icelandic politics at time when they appeared. In those years there were also intense clashes about the future of Icelandic poetry. The "revolution in form" was reaching its peak and people fiercely disputed the justification for poetic innovation, such as whether to write alliterative and rhymed verse as had been done for centuries before. Einar Bragi was not neutral on this issue either. As a member of the "atom poets" he was the most steadfast champion of the younger poets' campaign for a revitalization of poetic forms, but such innovations encountered forceful opposition. As the main spokesman for young poets he wrote many frank articles explaining the standpoints of the advocates of a renewal. He boldly fended off relentless attacks by those who refuse to accept any tampering with traditional verse forms and the accepted poetic style.

In the midst of this warfare, in 1953, Einar Bragi founded the magazine Birtingur which he edited for the first two years. In 1955 he brought in collaborators and the publication was expanded. Published until 1968, Birtingur was the forum for Icelandic modernism. It was produced by people from all branches of the arts who wanted to reinvigorate and renew the entire spectrum of Icelandic art. Einar Bragi was the magazine's life and soul throughout.

But it was not only in the public arena that Einar Bragi championed new poetry and artistic innovation. His poetry itself contains the clearest arguments that a renewal of poetic forms was not only timely but also necessary if poetry were to advance. His poems are clear examples of artistic creation based on an ancient heritage yet infused with fresh expression. This is clearly seen in his third collection, A Gathering by Night (Gestaboð um nótt), published the same year he launched Birtingur. The title poem is in a kind of chant form, exocentric, rich in imagery and fantastic: its succinct lines, alliteration and rhymes endow it with an exceptionally fast-paced and capricious atmosphere. Apart from the prose poems, the other poems in the book are concise and predominantly metrical. A number of prose poems are included, a form he would cultivate closely afterwards. One example is the prototype of a prose poem that was later given the title "Night Eyes" and shows an affinity to the herring village poems mentioned above. The only prose poem that had appeared before was "Thaw", which he has changed little over the years.

A strict revisionism has characterized Einar Bragi's approach to poetry from the outset and emerges in all his books. He is continually polishing and reworking those of his poems that he deems worthy of living on; others he would like to condemn to oblivion. His books not only present new poems, but also re-creations of earlier ones. This is a carefully thought-out approach and policy on the poet's part. In an appendix to A Gathering by Night he states this perspective in clear and forthright terms: "A poem, unfortunately, is never fully written. Of 55 poems and prose sketches in my earlier books, six are printed in new versions in this volume. The others will never be reprinted."

Rain in May (Regn í maí, 1957), Einar Bragi's next book, is an exceptionally beautiful collection, containing only 13 poems and the same number of illustrations by Hörður Ágústsson. Only one of the poems had appeared in his earlier books, and two in Birtingur. Many of Einar Bragi's most beautiful poems are found here, including the title poem and "Con amore", which was later renamed "Love Song". This poem is unique for the unprecedented values in which it measures female beauty and the rich felicity of imagery in which this is expressed:

I love the woman naked

with the nightingale in her eyes,

newly awoken and lily-scented

anointed with white morning sun,

the woman young and pregnant

with red-budded flowers

on pink tussocks

restless from yearning

for thirsty gatherers of nectar,

the woman proud and triumphant

showing the whole world

her spring-sown fertile field

where the wonder grows in the dark

porous soil: grows

Naturally this poem has been reprinted, and its author has not altered a single word. Rain in May also contains "Nocturne", later renamed "The car draws a red vein". As is common knowledge, people have been reluctant to admit cars into poetry, except in comic verse, and it has been considered a somewhat unlyrical phenomenon. This poem deals for the first time with human life in a car, which here is a fully valid part of urban life. We look through the windscreen of a car as it drives through the city on a rainy evening:

On a polished patch

on the windscreen's grey haze

they swirl in white smoke:

smiles hands impetuous lips

wine-bottles glowing flies

fluttering silent

All the poems in Rain in May withstood their creator's next revision and were reprinted in the selection Clear Ponds. Poems 1950-1960 (Hreintjarnir), published in 1960 and again in 1962. It includes five poems not found in his earlier books.

Besides Clear Ponds, Einar Bragi has produced three selections of his verse, each containing several new poems but largely comprising his earlier work, sometimes revised or retitled. Within Sight. Poems 1950-1970 (Í ljósmálinu) was published in 1970. Of the 47 poems in this collection, several were fairly recent: ten were printed the year before in a small volume titled When the Ice Breaks (Við ísabrot) and rank with the very best of Einar Bragi's work. One of the most memorable is "Waiting", about the creation of a poem which grows from a seed and becomes a tree, and about the poet's creative emotion. Its imagery is particularly felicitous – with its allusion to the god of poetry – and it is metrical in composition with half-rhyme for the most part, turning to full rhyme towards the end:

They rest in silence and grow: seeds sown in spring

and be yourself the nurturing, caring soil,

rain sun and wind, sky earth and seathey rest in silence and grow: become a tree

waiting winter-bare alone and yearning

to feel its bark pressed by tiny noses.Then the noble ash tree rumbles and welcomes

Odin, consecrated to both song and silence.

(First published in When the Ice Breaks (1969))

In a postscript to Within Sight the poet again discusses his working techniques and attitudes to poetry, exhibiting a rare stringency and discipline towards his own work. Claiming that he has never been a prolific poet, he goes on to say: "It could be said that I have always been writing the same book, like old Walt Whitman, the poet of whom I am fondest of all. Each person has his own way of working, and little can be done about that: It is mine, after all. I can only ask careful readers never to pay heed to other books of my verse than the most recent one, and to try to lose the others, if they have not done so already."

Since writing this, Einar Bragi has produced two more collections. In 1983 he published a collection of original and translated verse, illustrated by Ragnheiður Jónsdóttir, under the straightforward title Poems (Ljóð). The selection has been pared down so ruthlessly that it includes only 64 original poems. Nonetheless, this is more than any of his previous books contained, and 16 of the poems were previously unpublished. Once again this recalls the postscript to Within Sight, where Einar Bragi says he has always "considered it an achievement to manage to complete one presentable poem for each year of my life." On closer scrutiny, the number of poems in most of his books actually does appear to correspond to the years of his life. But Einar Bragi abandons this correspondence between poems and years lived in his most recent book, Light in the Eyes of Day (Ljós í augum dagsins, 2000), which contains only forty, of which three are new.

Reworking

The collection Poems comprises 48 poems from his earlier books. Only a few fragments are admitted from his first book, three stanzas in all. Einar Bragi's practice of constantly revising his work may be traced, for example, through the poem which was eventually given the title Wave Poem. Originally this formed part of a longer poem and has twice changed title, but the following stanza has withstood all revision without a single word being altered:

A little lad

played on the shore

and laughed,

the white wave

lured the child's

mind.

The poet wrote this in memory of his father and in effect it encapsulates the life history of a fisherman in particularly succinct and closely wrought form. The second stanza was slightly modified later and runs as follows:

A long life

of joy and discomfort

at sea,

the black wave

tossed the corpse

and laughed.

This poem is in all Einar Bragi's books except A Gathering by Night.

Another example of revision is the progress of the poem eventually called "Child":

White pages

in a book

awaiting

the poet

unwritten

open.

This concise poem exemplifies a rare aptitude in imagery: only a single image which nonetheless carries wide-reaching allusions. Indeed, many modernists strove to encompass a wealth of material within each image, enabling much to be said in few words. In its entirety the poem is a single metaphor, with the association made through its title. Originally this poem was two lines in another one which had five stanzas and was called "Love Verse" in A Gathering by Night. The text printed in When the Ice Breaks was the same as above, but with the title "A Child's Hands". The following year it was called "Child" in Within Sight.

As a poet, Einar Bragi has a long and distinctive career behind him. His poetry bears witness to a highly meticulous and methodical approach and care and respect for the language, and its main strength lies not least in rich and succinct imagery. Einar Bragi's ambitions has always set great store by creation of imagery. In 1955 he wrote in Birtingur: "The reality of a poem is not the poetic theme itself, but its image. In a good poem the theme vanishes into its image, becomes it." (Birtingur no. 4 1955, p. 38.)

Themes

The themes with which Einar Bragi is most preoccupied are stated outright in "Untitled poem" with which he opened his selections of 1970 and 1983:

I who love words

named ever humble

woman, man

life soil water,

on my lips burned

the weakest verb

to love,

gently I felt placed

upon my heart:

without me the poet

can say nothing.Who are you?

I am the silence.

(First published in When the Ice Breaks (1969).)

Human life, love, nature – all these are intertwined in his poetry, as revealed in some of the examples quoted above. People and their fates, experience, joy and death are the themes of many of the poems; daily life and everyday chores. There are, for example, the poems about village life, monuments to people in toil and hardship in many parts of Iceland, whose fates engage us all when they appear before us in this powerful imagery. Einar Bragi has taken a firm standpoint on the issues of his day and written many critical poems. Criticisms of social injustice, military violence, political hypocrisy and all manner of pretence are presented either with irony or images from nature. There is a peculiar satirical criticism in "Patriotic Poem" which deals with superficial ceremoniousness, at once amusing and tragic. The national emblem, the Maid of the Mountains, abandons her traditional role on National Day and instead of reciting from the stalwarts of Icelandic patriotic poetry she starts talking about the eider duck and its struggle for survival; she is on the verge of tears and the crowd is moved. "The eider was always my bird," she says at last – then:

she watches over her eggs,

not caring for food,

sipping only rain from blades of grass

to quench her direst thirst

while she waits,

waits to be able

to accompany her children

that short way

from the soft downy nest

to the predator's corpse-yellow beak.

(First published in When the Ice Breaks (1969). Einar Bragi describes the provenance of this poem in Times Were Different Then. vol. 1, pp.. 166-67.)

This animal fable, recounted by the sobbing Maid of the Mountains, can easily be extrapolated onto social issues, in the narrow and the broader sense alike. But the Maid of the Mountains says precisely what must never be spoken on solemn occasions, because then all social misdeeds are glossed over and everyone is supposed to be joyful at vanity dressed up in its Sunday best.

"Love Song" about the beauty of a pregnant woman was cited earlier. A similar association between love, beauty and fertility occurs in other poems, e.g. the prose poem "Rain in May", and love is invariably enveloped in admiration and care, for example in the short "Youth":

The breeze wakes

the water in the bright small hourslikewise love wakes

waves in your bloodnew every night.

(Light in the Eyes of Day, p. 7. First published in A Gathering by Night.)

Nature assumes diverse figurations in Einar Bragi's poetry, performing all manner of roles. Sometimes it is a mirror held up to society, as pointed out above, but it is also a bringer of life and an image of beauty, with close psychological links. "Refrain" runs as follows:

While the earth sleeps

wrapped in its white cloak,

the cheerful warmth moves

with the dream of spring through its veinsI do not hear their murmuring,

but feel in my blood

a silent suspicion

of a green needle beneath the snow.

("A Conversation with Visitors". Birtingur nos. 3-4 1958.)

And an even more economical poem about the relationship between man and nature displays the later in a magical sense. Titled "When Night Falls", it is as follows:

I vanish,

but white arrows

of strange lights

that burn in the day's eyes

drop onto my path,

light up my steps

in the grey sand

when night falls.

Einar Bragi's poetry has been translated into many other languages. Etangs Clairs (1968) is Régis Boyer's French translation of Clear Ponds. Selections include the Swedish Pilar av ljus (1976), translated by Inge Knutsson, and Knut Ødegård's Norwegian translation Regn i mai (1973). Many poems by Einar Bragi are included in Poesía nórdica (1995), translated into Spanish by José A. F. Romero. Translations have appeared in many more anthologies, and in magazines published in various countries.

Diverse writings

While the above discussion has been confined to Einar Bragi's original poetry, he has also produced monumental achievements translations of poetry from many countries, in particular Scandinavia. Translations were already included in his first book of verse, and in fact recur through most of them. He was co-editor, with Jón Óskar, of Modern Foreign Poetry (Erlend nútímaljóð, 1958) and made a large part of the translations himself. A number of Einar Bragi's books contain only translated poetry: Ravens in Clouds (Hrafnar í skýjum) is a collection of translated verse published in 1970, and he has also translated the work of Knut Ødegård (1973) and Gunnar Björling (1975) and an anthology of Latvian poetry. Furthermore, he achieved an exceptional cultural feat with his translations from and introductions to the work of poets from peripheral areas: poetry from Greenland in Summer in the Fjords (Sumar í fjörðum, 1978) and Saame poetry in Whisper to the Rock (Hvísla að klettinum, 1981).

This, however, only represents one aspect of Einar Bragi's translation work, which extends to novels and plays by a large number of authors as well. Particular mention should be made of his translations of virtually the entire corpus of work by two of the greatest Nordic dramatists: Strindberg: Plays I-II (Leikrit, 1992) and Ibsen: Plays I-II (Leikrit, 1995).

Einar Bragi has produced an extensive range of other work. He has written a memoir of his early childhood, Of Man Thou Art (1985), in which he describes growing up in Eskifjörður and gives a perspicacious portrait of his parents and the details and conditions of their lives. Another more comprehensive work, and also written from another viewpoint, is the history of Eskifjörður, Eskja I-IV (1971-86). This is a treasurehouse of local lore, skilfully and knowledgably compiled and written. With it, Einar Bragi has amply rewarded his childhood village, "hunger bay", for fostering him. In the course of the years Einar Bragi has apparently taken a growing interest in the history of ordinary people and their way of life. A work of this kind is his collection of writings and narratives from times past, Times Were Different Then I-III (Þá var öldin önnur, 1973-75), describing people and events, especially in the east Skaftafellssýsla district where the author's roots lie. The work contains both portraits of ordinary life in times of old and the author's own memoirs from these parts.

In 1982 Einar Bragi produced a peculiar book. Called The Loser, it describes the Danish merchant Jakob Plum, who worked for the Danish royal trading company in Ólafsvík in the eighteenth century and later became a private merchant there. The book is in the form of interviews taken by an Icelandic contemporary of the Danish merchant, and based on two books which Plum wrote about his work and his acquaintances with Icelanders.

All the above goes to show the rich variety of literary work in which Einar Bragi has been engaged. He has also published work by other authors and written about them, including "The Lily" by Monk Eysteinn Ásgrímsson, a selection of poetry by Jón úr Vör, literary essays by Bjarni Benediktsson from Hofteig and the stories and poems of Stefán Jónsson.

Furthermore, Einar Bragi has written numerous articles and essays on literature, other branches of the arts and social issues, which have appeared in magazines and newspapers. His writings about approaches to poetry are an important contribution for studies of the renewal which took place in Icelandic poetry from the middle of the last century onwards. From the very outset of those upheavals he championed new attitudes and presented carefully argued criticism of Icelandic poetry. In a poetic dialogue in Birtingur he describes his attitude towards modernism:

To my mind it is above all a rebellion against stagnant forms, mechanical sequences of alliteration, uninspired verbal foliage, spiritless bombast, unreworked external description, imageless narrative and all manner of metrical "ethnic" rambling which was suffocating the poem – and at the same time it is an effort towards renewal: the creation of new poetic forms, purification of poetic diction, innovations in imagery, similes and association of ideas, with the overriding purpose of giving the poem itself pride of place.

Eysteinn Þorvaldsson, 2001

Translated by Bernard Scudder.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 475, 477, 481, 483, 494

On individual works

Pilar av ljus

Palm, Anders: "Ólafur Jóhann Sigurðsson. Du minns en brunn ; : Einar Bragi. Pilar av ljus"

Gardar 1976, vol. 7, pp. 78-80.

Awards

2001 - Honorary Member of The Icelandic Writer´s Union

2000 - The Swedish - Icelandic Culture Prize

1999 - The Swedish Academy´s Translation Award

1998 - The Library Fund´s Honorary Award

1995 - The Translation Fund´s Honorary Award

1986 - Eskifjörður Town Honorary Citizen

1969 - The National Broadcasting Service´s Writer´s Fund

Poesia. Anno XVIII. N. 200 - Dicembre 2005

Read moreÉg litast um í leit...

Read more

Ljóð í Cold was that Beauty... (Poems in Cold was that Beauty...)

Read more

Ljós í augum dagsins

Read morePoems in Wortlaut Island

Read moreVaikke jiehkki jávkkodivccii

Read morePoems in Time and The Water

Read moreLjóð í HUGUR, offerts á Régis Boyer pour son 65' anniversaire

Read morePoems in La Tradukisto

Read more

Víðernin í brjósti mér: ljóð

Read more

Undir norðurljósum

Read moreHandan snæfjalla: ljóð

Read moreKaldrifjaður félagi: ljóð

Read more

Bjartir frostdagar: ljóð

Read more

Móðir hafsins : ljóð

Read more

Leikrit I - II (Ibsen)

Read more

Innreið nútímans í norrænar bókmenntir

Read more

Leikrit I - II (Strindberg)

Read more