Bio

Guðmundur Ólafsson was born born in Ólafsfjörður on December 14, 1951. He graduated as a athletics teacher from the Iceland School of Physical Education at Laugavatn in 1972. He taught at the elementary school in Eskifjörður during the winter of 1972 – 1973 and then at Barnaskóli Akureyrar (Akureyri Children's School) 1973 – 1974. He moved to Copenhagen in 1974 to study Danish at The University of Copenhagen and then did theatre studies at the same school from 1975 – 1977. After that, Guðmundur studied acting at the Icelandic School of Drama and graduated in 1981.

Since then, he has been an actor and worked in theatre, as well as being a writer from 1986. He has taken a few side- steps during this time, among other things done radio programs for Bylgjan radio. He has acted in numerous plays, mainly with the Reykjavík Theatre Company, both in the old Iðnó theatre by the Reykjavík Lake, and at the City Theatre. He has also acted in plays staged at the National Theatre and by Alþýðuleikhúsið (The People's Theatre). Guðmundur has had rolls in movies and tv shows.

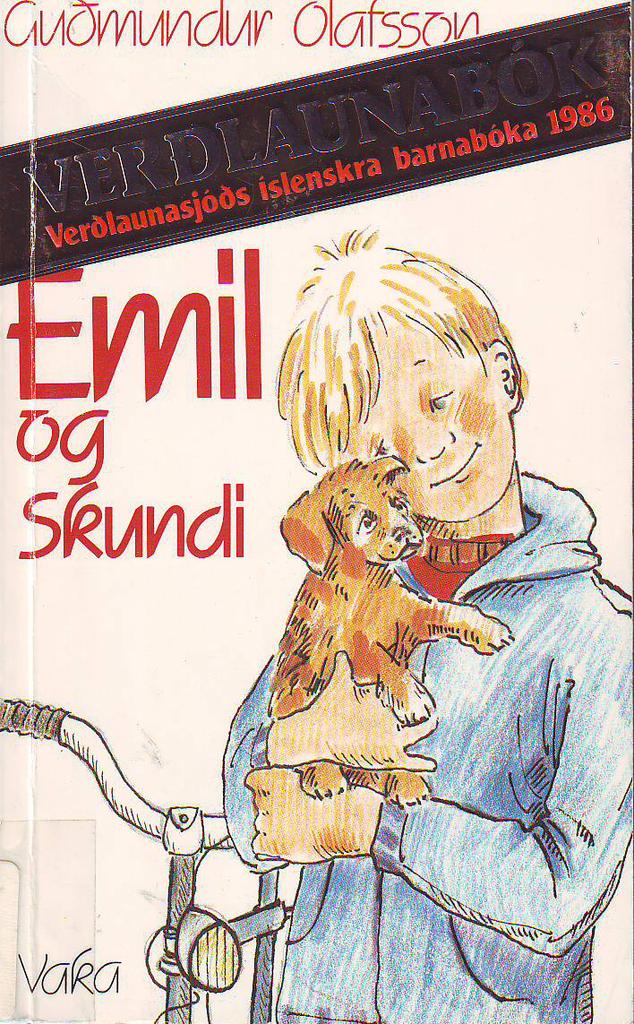

The children's book Emil og Skundi was Guðmundur's first published book. It received the Icelandic Children's Literature Prize in 1986. Two other books about the adventures of Emil and his dog Skundi have appeared, as well as a movie based on the books (Skýjahöllin). Guðmundur has sent forward more books for children and teenagers and received the Icelandic Children's Literature Prize for the second time for one of them, Heljarstökk aftur á bak (A Backwards Summersault). Guðmundur has also written plays, scripts for television programs and done adaptions for the stage. He has also worked as a translator and his stories have been published in newspapers, magazines and collections.

From the Author

From Guðmundur Ólafsson

Ever since Inga from Kot taught me how to read when I was six I have been doing just that. At first it were the traditional reading exercises as in The little yellow hen, who thought one socialism and then came the tiresome sentences about Ása who had a yew and Ari who had a belt or was it Óli who was the owner of the belt? Later I got to know the Blue jug and the remarkable and terrifying book about Láki the earth elf who was like a diving board for me or maybe just a running start into the terror of Dísa the fairy and Rauðgrani the dwarf. Some books you did not have to read, they where read to you, either at school, like Bljáskjár who was so influential that for a while I believed that I myself was of noble decent, at least the son of a fishing magnate (and this was even before people started to turn the fishing quota into big business) or you listened to the stories on the radio like the Magic cave which was wonderfully read by Anna Snorradóttir. Little Kári and his dog Lappi were also hanging around and Snjallir snáðar as well as Högni the lighthouse boy. Then came the books about Árni from Hraunkot and Rúna and Gussi and Svarti-Pétur, not to mention Enid Blyton; with plenty on offer: The Fantastic Five, The Adventure Books, The Mystery Books; all about these fine youngsters who ALWAYS had to deal with criminals during their summer break and also ALWAYS came out on top.

Somehow I got the feeling that the criminal element far north in Ólafsfjörður was not up to scratch, at least if you compared it with the highly dangerous surroundings that Blyton’s protagonists had to put up with. One heard at the most of someone who had been caught brewing their own alcohol, and that was hardly thought of as a crime, that was considered to be a healthy survival instinct. Then there were the books about Benny the clever fly-boy in the RAF, whose full name was probably Benjamin Biggles and in Iceland Biggles was pronounced the way it is written. Bob Moran and Tom Swift entered the scene as well and the Danish books about Jói and Kim. And from the Scandinavian selection there were also the books of Ann Cath Vestly about Fathermotherchildrenandcarandthehouseinthewoods as well as Óli Alexanderfílíbommbommbomm and one also got to know the children at Svartatjörn [Black lake] and the difficult life of Sandhóla-Pétur and someone had a few Danish issues of Donald Duck. (But where was Astrid Lindgren?) At a more southerly point on the globe we find Heidi and Peter in a beautiful and healthy landscape in the Alps where they drank goats milk and ate goats cheese which cured everything, (this was before the days of lactic intolerance), in between life affirming yodelling sessions. On home ground Little Hjalti was having a hard time in a very difficult Icelandic reality but we find the young ram Salomón svarti in a lighter mood and his friend Bjartur. And we must not forget all the school poems about Sörli and the golden plover and Óli and Snati and the old wise man who sat in the clover and my sister who was out in the street. (I am afraid that Herdís Storgaard would not approve of that sort of behaviour.) And then we oh’ed and ah’d a bit and loved our land. In the children’s magazines Æskan and Vorið we found constructive fables that confirmed that one should not steal or be naughty and first and foremost that fathers should not drink alcohol because then their children would die like little Villi. And with a little maturity came the exciting loves and fates of nurses, doctors, the sons of local dignitaries and lighthouse keepers in the stories of Ingibjörg Sigurðardóttir, always published first in the magazine Heima er best.

And before you knew it you where taking the first steps towards world-literature and slowly I bought in Steini Hólm’s shop all the issues of both The man with the iron fists and Count Basil. These where glorious times. Both fought against crime and corruption each in his way. Basil, this mysterious and intelligent man who used brains rather than brawn and then the beautifully formed iron fisted man, who sure enough was sharp witted but also had the physical attributes to use against the criminal rubble. Then came the books about Zorro, who’s real name was Don Diego de la Vega, and no one could beat him in a sword fight and my mother made me a black cape and to go with it I wore green trousers made from an elastic material [stretch pants] (that for some mysterious misunderstanding were called “start-trousers”, which is of course a much better name) but it was tricky to get the mask to work. I did not see anything when I put it on, except dead ahead; nothing to the sides or up or down unless I moved my head and If I did that the mask slipped and that complicated things further and most likely I looked like a chicken more than a freedom fighter down in Mexico. The mask was therefore soon abandoned, also because it soon transpired that every one knew who you were despite this disguise. Prince Valiant was a distant relative of Zorro and we must not forget the Blue books for boys and Red books for girls.

Tarzan was not far away after I managed to acquire the first books at a book fair that came to town one summer. There I also found in paperback the books about my favourite, Lightfoot the Indian. The Mohican who could run like the wind for days on end, fast and silently, who was such a terrific tracker that even one broken twig could tell him a long story about the person who broke it. And he was also very noble and that you could tell not the least from his eyes, there you could also see the pain of the lonely man who was stuck in the grey area between two cultures. Yes, Lightfoot was my man.

And more heroes joined the club and yet again it was the printing shop of Oddur Björnsson in Akureyri that supplied the goods. This time round it was the books of Rafael Sabatini. Yes, I think there were twenty one of them and I got them all for Christmas. They were all bound with hard covers and had a red spine and with great names such as The Viking, The Loiterer, The Bastard, The Sea Vulture and all were about the adventurous lives of European nobility, probably during the seventeenth or eighteenth century when honour and chivalry mattered. And the village library, where this wonderful smell of books which I have never since found anywhere, which contained a wonderful treasure that people said my cousin Agnar had read in its entirety.

Stefan Zweig’s story about Napoleons police commissioner is memorable and Anna Karenina, which I thought was simply a good Russian thriller instead of one of the world’s literary treasures. Had I known that at the time it would most likely have got postponed until a later date. And my grandfather had both Troubles on the highland roads and The Story of Snæbjörn of Hergilsey and they were read, just because they were there on the shelves. And then there was a bit of sniffling for poor Solon Islandus who had such a hard time of it just like the lame boy in the Magic Garden where there was a bird that had the wonderful name of “glow chested robin”. And then I was suddenly taken away from a sunny, decorative garden at an English country house and brought to the barren and chilly heaths in Iceland where Halla the fictional character of Jón Trausti lived on a small farm; and she was also dramatised on the radio (just like Hidden Eyes that where so frightful that you did not go out after dark whilst that series was running). And then I sneaked a look at Hjalti who the regal and rich woman Anna of Stóruborg took as a lover. I say sneaked, because it was considered a most daring tale when the said lady slipped into bed with the shivering sheep herder to warm him up a bit. And then came Alastair MacLean and Desmond Bagley and all of a sudden Jack London had sneaked onto the reading list with all kinds of Alaskan Adventures and The Boxer; it was a long time before I knew that he was a remarkable writer and a communist. And at this point the teenager was ready to tackle proper literature and I read Fjallkirkjan by Gunnar Gunnarsson. And then, when my father came home from the herring-fishing season late in the summer of 1967 he gave me Heimsljós by Halldór Kiljan Laxness, a copy he had bought at Seyðisfjörður. And I read: “He stands alongside an oystercatcher and a purple sandpiper down by the seafront below the farmhouse and watches the waves move to and fro.”

And that was the point of no return.

It is because of these books and thousands others that I write.

Guðmundur Ólafsson, 2002.

Translated by Dagur Gunnasson.

About the Author

On the Works of Guðmundur Ólafsson

Guðmundur Ólafsson was born in 1951 in the town of Ólafsfjörður and as well as being an author he is also a well-known actor. He has published one short story and five books for children and youths. Three of his books are about Emil and his dog Skundi that have been dramatised in Skýjahöllin, a film by Þorsteinn Jónsson. For his first book Emil og Skundi Ólafsson received the Icelandic Children´s Literature Prize and for the story Heljarstökk aftur á bak [A standing backflip] he got the same prize a second time in 1998. In the story Klukkuþjófurinn klóki [The clever clock thief] Guðmundur tells a tale of a group of boys in a seaside village and in the short story “Faðir vor” [The Lord´s Prayer] the same characters get a look in, even if the material gets a different treatment. The short story was published in Vertu ekki með svona blá augu [Do not have such blue eyes], a collection of short stories. The books about Emil and klukkuþjófurinn are stories meant for children, but Heljarstökk aftur á bak is a typical book for teenagers. The short story is in a collection aimed at teenagers but suits equally well for grown-ups.

This article will first deal with the books about Emil, then Heljarstökk aftur á bak, then Klukkuþjófinn klóki and finally the short story “Faðir vor”. The date of publishing is not used for guidance but rather the common characteristics of the work.

Even if the stories within Guðmundur Ólafsson´s body of work are quite different, there is still not a certain development or evolution to be seen. He uses different styles to achieve different effects and I find his work all equal in quality.

Emil, Skundi, Gústi, Gunna and grandfather

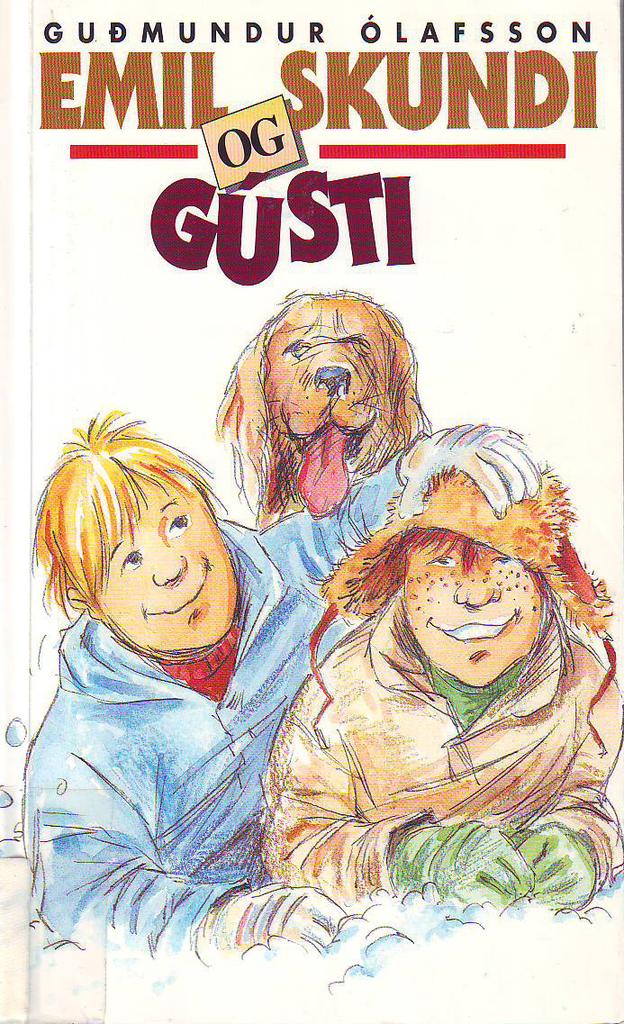

The first book Emil og Skundi was published in 1986, the second one Emil, Skundi og Gústi was published in 1990 and the third one Emil og Skundi – Ævintýri með afa [Emil and Skundi – An adventure with grandfather] in 1993. The latter books are independent sequels. The first one spans the time when Emil is eleven years old about to turn twelve; the second book takes place the next winter and the third the next summer. The stories delve into certain chunks of time in the life of Emil, the first spans about a week in his life, the second spans the school year and the third only a few days. Emil og Skundi tells the story about how Emil gets to own a puppy called Skundi. Emil, Skundi og Gústi focuses on the friendship between Emil and Gústi and their production of a school play. Emil og Skundi – Ævintýri með afa is about a trip Emil, Gústi and Gunna, who is the little sister of Gústi, take to Emil´s grand father who lives in the little town of Ólafsfjörður.

The stories are realistic, Emil is a ordinary boy in Reykjavík and the action could easily take place in reality. The stories sometimes allude to heroic adventure stories about children as if to accent the difference:

Í bókum var svona lagað svo auðvelt. Þá fundu menn sér bara hlöðu og lögðust í grænt og hlýtt heyið. En hér var ekki hlýtt einsog í útlöndum. Og svo var hann þreyttur, svangur og kaldur.

(Emil og Skundi, s. 108)

[In books this kind of thing was easy. People simply located a barn and lay down to sleep in the green and warm hey. But here it is not warm like abroad. And he was tired, hungry and chilled to boot.

(Emil og Skundi, p. 108)]

The realism is not pure, it has a tint of the adventure format. Gunna, e.g. catches a huge salmon and Gústi gets much praise for his play. And all the stories have a happy ending, there are no loose ends, which does give the readers courage and strenghtens their faith in life.

Emil is a blonde and delicate boy. At first he lives in the western part of Reykjavík, but in the second book he has moved to a villa in the suburbs of Breiðholt. He is an only child in the first two stories but in the third he aquires a litle sister. Emil´s father is a blacksmith and his mother works all day in a grocery store and in a kiosk in the evenings. Gústi is a year older than Emil, big and ginger. He lives with his mother and Gunna, his litle sister. His mother works in an old peoples home and as a cleaner in the evenings, so Gústi is often forced to baby-sit his sister.

All the stories are divided into short chapters where the plot drives the precise storytelling. In the first book there are for instance 22 chapters and in most of them Emil and his friends deal with some obsticle or unexpected events and that supplies the main thrills. The narrative is in third person and even if the author can see into the minds of the characters as he pleases he keeps mainly to Emil and his experience of events. When something important is going on he often changes the scene, shows what is happening elswhere at the same time, much like people do in films. The narrative is very much staged and full of dialog which makes the first book ideal material for a film. The dialog describes in a very realistic way how people communicate and the author has a good sense of every day language. His sense of humor allows him to tackle sensetive matters in a thrilling plot. Emil is a clever boy and often very grown up and his conversations with grown ups are often entertaining:

-Má bjóða hans hátign kaffi?

-Já takk. Kannski pínulítið tár, sagði Emil einsog hann hafði svo oft heyrt Jósa segja.

(Emil og Skundi, bls. 37)

[-Would his highness like some coffee?

-Yes please. I´ll take just a drop, Emil said just like he had heard Jósi say.

(Emil og Skundi, p. 37)]

Gunna, Gústi´s little sister, is particularly funny, talks a lot and is never want for words:

“Gúðti, kúðti!b Þa er þíminn. Bleþþþ og takk fyðið þpjallið.”

(Emil og Skundi, s. 62)

[Gúthti, kúthti! Thu thone is forth you. Byeeee and thanks foth the chath.”

(Emil og Skundi, p. 62)]

Skundi the dog is also full of life and his presence livens the books up. He is also a wise and faithful friend as we have seen in older stories about animals. There is a clear social critisism in the stories, Emil´s parents are building a villa and have to take on a lot of extra work and Gústi´s mother has to work all hours to support the family. The grown-ups in the story are therefore quite often tired, annoyed and even unfair, as happens when Emil´s father breaks a promise and forbids him to have the dog. That is when Emil decides to run away to his grandfather who lives in Ólafsfjörður but Emil also seeks out the company of an old carpenter, Jósi, and a strange dog lady who like the grand father have time to chat with him.

Since the story is told from the viewpoint of children it poses questions about why society is like that, why parents can not spend more time at home, why people need to build large villas and so on. The parents try to explane things the best they can so that both points of view are served. The story also shows that parents make mistakes they regret and ask for [their children´s] forgiveness. Sometimes they do not listen to their children and forget what matters the most, their loved ones. But Emil´s parents and Gústi´s mother love their children, they are plagued by a guilty consciousness and try to do their best and to be good parents.

Generally one can say that the spirit of good will is prevailent in the books. Emil and Gústi are both very hard-working and good boys and they are especially good to Gunna who is actually very manageable. Both boys achieve their goals by being hard-working, Emil saves up enough money on his own to be able to buy Skundi the dog by selling newspapers and helping the old carpenter. Gústi puts a lot of effort into writing plays that are later produced as school plays that are critically acclaimed.

Emil and Gústi are also at that stage, 11 and 14 years old, when they have started to understand that live is far from simple. The stories describe how they respond to certain problems and the questions that crop up. In the first book Emil responds to the growing tension and unhappiness of his parents, in the next one it transpires that Gústi is keeping a secret, his father is one of the homeless drunkards in the town, and in the last one the children have to help Emil´s grandfather when he gets some sort of heart attack whilest camping with them in a uninhabited fjord where conditions are difficult. The boys overcome the difficulties and learn certain truths. In the first book Emil learns that his parents love him and that he must not scare them by running away. It is also stressed that it is hard work and a responsibility to own a pet. In the second book the theme is the value of friendship, Emil´s mother explanes that friends help each other by being there and listen, that it is not possible to solve all problems. In the same fashion does Gústi explane to Emil that his father can not help himself and that all Gústi can do is to wait and hope that the situation will become slightly better, he also explanes that his family will not be reunited. In the third book Emil battles with the fact that his beloved grandfather almost died and the fact that children are not neccesarely born at the right time, like his sister and that the reason is not lack of love but money.

A standing backflip

Heljarstökk aftur á bak is a story for teenagers, it tells the story of Jón Guðmundsson and his first winter in high school (Menntaskólinn í Reykjavík). When he is registering, Jón sees a girl and is overcome by love. The story then describes Jón´s lovesick state, the emotional rollercoaster and the build up to the first kiss where the story, in the style of Mills and Boon, ends:

Oft hafði hann í draumum sínum ímyndað sér hvernig það væri að kyssa þessa guðdómlegu stúlku en þær ímyndanir voru sem hjóm í samanburði við raunveruleikann. Hann lokaði augunum og sá stjörnur falla að himnum ofan og heyrði fegurstu klukkur klingja og gott ef ekki var stödd lítil strengjasveit einhvers staðar í nágrenninu!

(Heljarstökk aftur á bak, s. 17)

[In his dreams he had many times imagined what it would be like to kiss this divine girl but those fictional kisses where pale in comparison with reality. He closed his eyes and saw stars shoot from the sky above and he heard the most beautiful bells chime and was that a small string quartet somewhere in the neighbourhood?

(Heljarstökk aftur á bak, p. 17)]

Alongside the love story there is a description of Jón´s family life, life at high school and his friends. The book is more farse like than the books about Emil and there are larger descriptive bits although dialoge is still prominent in the text. Jón is like Emil a very normal boy, even too normal, and like many teenagers he takes care not to stand out in a crowd. The farse-like elements are there to stop the story from taking itself too seriously, some characters are too exagerated to be clichés. The main character, Jón and descriptions of his dreams are in the foreground, daydreams as nightmares give an insight into his mind but the author also uses such descriptions in the books about Emil as a fun ploy. The daydreams are of course all about fame and fortune but in the nightmares events from real life merge and are portrayed in a distorted way.

The story is about Jón´s coming of age. It is difficult to start a new school, he is having trouble with math but with his friends help he is able to improve immencely. At home he helps his sister who is having a hard time and at a school event he stops being ashamed of his parents and lands second place in a karaoke competition. Jón deals with different problems and gains strength from it.

The story takes place in modern Reykjavík and takes a peek at issues such as teenage drinking, sex and anorexia. The authors view is clear because the characters do not have much of an inner struggle with these issues. Jón does not drink at the beginning of the book and although he accidentally becomes intoxicated once it is clear that that will not happen again. His sister loses a lot of weight but luckily it turns out to be anorexia in its beginning stages. The image given of the life of a 16 year old teenager is therefore rather simple and smooth. The story is funny, romantic and ends well which is a refreshing change from books about world weary teenagers and their brush with criminality. This is a well written, but a slightly formulaic book which has something not many books in popular literature have, a consciousness, it mediates emotions every one recognises but other than that it does not try to be realistic.

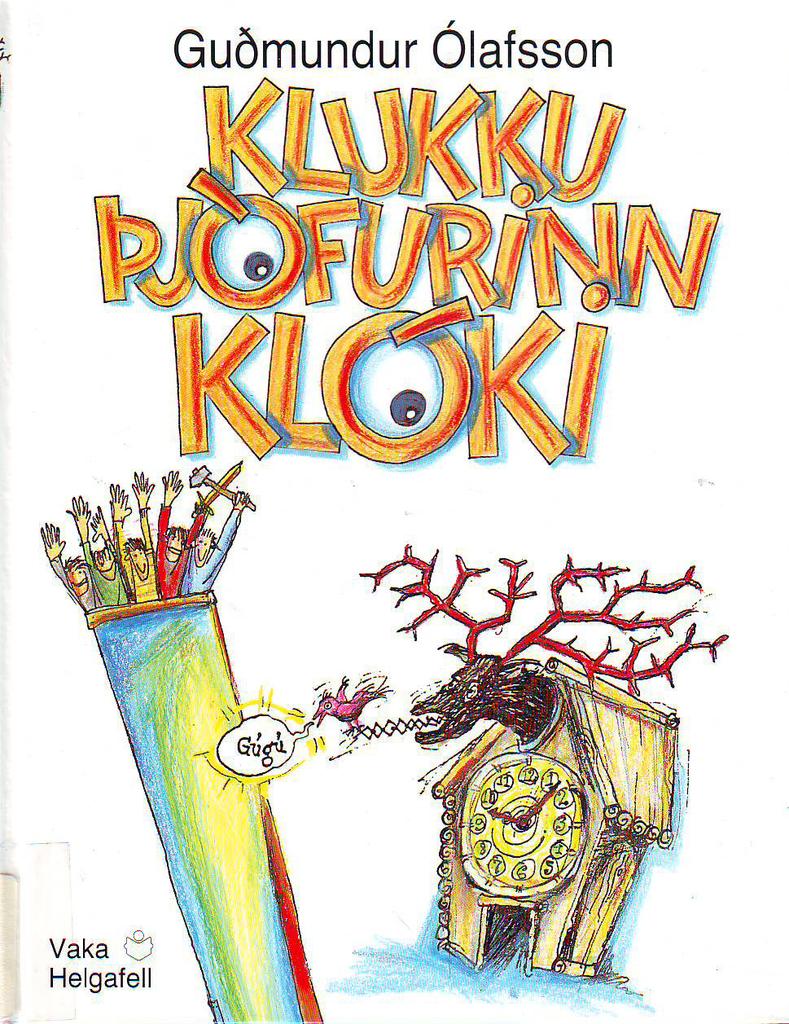

The clever clock thief

In Klukkuþjófurinn klóki [The clever clock thief] the crazyness takes control. It is about a group of boys in a small seaside village and mostly about two cousins who live together in the same house. The cousins are so close that they wake up at the same moment and mimic each other in every way possible. The story takes place at a time when mothers took care of the home and people drank Valash, Jollí-Kóla and Cream-Soda. It begins at the beginning of spring break and ends when autumn comes. The story describes in an exhiting way how the kids build small play huts and plan a carnival, later the huts burn down and the search for the criminal begins, he is caught, punished for that and other crimes, the boys throw frosen cakes at a childrens birthday party and perform a play where the birthday boy is knocked unconscious.

The narrative is in third person and there are many asides and comments from the author. The plot is not solid like in the other books, it is rather the characters and the summer holiday that frame the action. The story focuses on the closed world of the boys, grown-ups do not enter the equation and it is for instance out of the question to involve them in the hut business. This is a nostalgic story, it shows a yearning for a lost time and conveys nicely the atmosphere of the era, small town mentality and fashion. The boys are for instance dressed in their Sunday best with ties at the last day of school and at the birthday party, they play at being Roy Rogers and Dale and at the carnival, Kobbi, one of the boys, manages to walk around in much too big Zorro boots.

Klukkuþjófurinn klóki is unlike the other stories by Guðmundur Ólafsson richly illustrated with pictures by Gretar Reynisson and the text and illustrations form a nice solid work. The pictures are black and white caricatures that are planted higledy pigledy even upside down. The author uses upper case lettering a lot to emphasise the impact of the words when something important takes place and sometimes he writes phonetically to show us the intonation:

- GÓÐILÆKNIRGETURÐULÆKNAÐÍMÉRTANNPÍNUNA.

(Klukkuþjófurinn klóki, s. 122)

- DEARDOCTORCANYOUCUREMYTOOTHACHE.

(Klukuþjófurinn klóki, p. 122)

Midway through the book, when the tension peaks and the boys decide to punish the main bully of the town, the one that burnt down their huts, the pages are black and the letters and pictures are white. The boys make a go for it late one night when everyone is still working at the fish factory. The black pages symbolise the darkness and the ghostly atmosphere of the evening, the moon peeks through the clouds once in a while and the boys can hardly see where they are going:

Ekki var laust við að beygur læddist að ýmsum, þegar í hugann komu sögur um sjórekin lík og hauslausa drauga, sem reikuðu friðlausir um. Kolsvartur sjórinn glefsaði ólundarlega í fjörugrjótið.

– Djöfuls myrkur! Tautaði Svenni.

(Klukkuþjófurinn klóki, s. 88)

[It is not impossible that some of them where a little bit afraid, when stories about sea-bloated bodies and headless ghosts that staggered restlessly about where hinted at. The pitch black sea snapped angrily at the rocks at the seafront.

- Bloody darkness! Mumbled Svenni.

(Klukkuþjófurinn klóki, p. 88)]

There seems to be a little bit too much darkness for the Icelandic summer nights but the tension is the main thing, not the realism. The bul y is punished and he lays low for a while but later he continues his wayward ways, the story ends without any transformation, a fun summer is over. The message is recognisable: Boys are and will be boys!

The lord´s prayer

The short story “Faðir vor” [The lord´s prayer] is connected to Klukkuþjófurinn klóki because the same characters appear and the scene is the same, a small seaside village and the stories take place in the same time span. The author places these stories clearly in the surroundings and the time of his own childhood, he was born in 1951 and was brought up in Ólafsfjörður. The main character of the story is an eleven year old boy who´s name is not mentioned but his three friends, Nasi, Himmi and Svenni are also characters in Klukkuþjófurinn klóki. That is as far as the comparison goes because the short story is serious and deals with the boy´s reaction to his friend Svenni´s death. The story is told in a third person narrative, which is very intimate, because most of the story is conveyed through the boy, how he experiences events. It is composed by five scenes, the first describes when two boys from the group meet after the death, how their world has changed and nothing matters any more. The second scene describes when the boy hears of the death of his friend on his way home from a trip, the third describes a compulsory visit the friends make to the priest, the fourth the funeral and the fifth how the boy bids his friend farewell and starts to play again.

When the friend dies the boy is filled with anger at god. The priest who sees himself as far more important than the boy, does not try to put himself in his shoes, but quotes the bible and gives standard and cliché answers. It is traditional that friends forward a greeting and that is why they go to see the priest, not for the salvation of their soul. The anger towards god is fearful, the boy fears that god will punish him but he takes the chance because he is not even sure anymore that god exists at all.

The story is very powerful; the lightly connected scenes form a whole where a lot is said with very few words. The tension between the surface and thoughts is strong, on the surface not a lot happens, the funeral is traditional, but the boy´s thoughts are zooming around and to him death is inconceivable and impossible to reconcile with.

The final scene where the boy “gives” his friend the gift he had bought for him, a small iron bird, by throwing it into the river, is symbolic. Earlier in the story he holds the bird in his hand in his pocket but here he lets it go, remembers his friend at their secret hideout and “agrees” in his own way not to return, without being reconciled with god since the innocence of a child´s faith is irretrievable.

Finally

To summarise quickly the main characteristics of Guðmundur Ólafsson´s work, it can be said that he gives readers a good insight into the mindset of children and teenagers, especially boys. Natural sounding dialog and clear scenes are some of his characteristics, in addition to his sense of humour which is natural and revolves more about how funny children are rather than jokes and isolated incidents. His work are therefore a fun read for everyone and also very healthy for grown-ups.

© Inga Ósk Ásgeirsdóttir

Translated by Dagur Gunnarsson

Awards

1998 – The Icelandic Children’s Book Award: Heljarstökk afturábak (A Standing Backflip)

1989 – The Reykjavík Theatre Company Playwrighting Competition: 2nd prize for the play 1932

1986 – The Icelandic Children’s Book Award: Emil og Skundi (Emil and Skundi)

Fader vår

Read more

Lísa og galdrakarlinn í Þarnæstugötu (Lísa and the Magician in Nextover Street)

Read more

Emil og Skundi - allar sögurnar (Emil and Skundi - All the Stories)

Read more

Heljarstökk afturábak (Backflip)

Read more

Emil og Skundi - Ævintýri með afa (Emil and Skundi - An Adventure With Grampa)

Read more

Emil, Skundi og Gústi (Emil, Skundi and Gústi)

Read more

Klukkuþjófurinn klóki (The Clever Clockthief)

Read more

Emil og Skundi (Emil and Skundi)

Read more