Bio

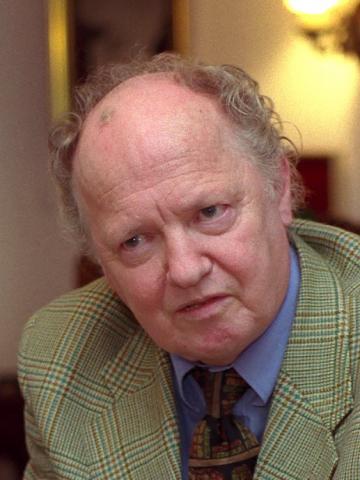

Gylfi Gröndal was born in Reykjavík on April 17, 1936. He studied Icelandic at The University of Iceland, and then took up a career in journalism. He worked as a journalist for more than thirty years, editing papers such as the magazines Fálkinn, Vikan and Samvinnan and the newspaper Alþýðublaðið. He also did numerous radio programs about 20th century writers for The Icelandic Broadcast Company.

For most of his career, Gylfi was first and foremost a writer. He started writing poetry at a young age, and his first published poems appeared in the collection Ljóð ungra skálda (Poems by Young Poets) in 1954, when he was 18 years old, followed by some poems in the collection Árbók skálda (The Poetry Yearbook) in 1956. He sent forward seven book of poetry, the last one was Eitt vor enn (One More Spring) in 2005. His poems have also appeared in collections in Iceland and abroad. Gylfi is however best known for his interview books and biographies that are close to 30 in number. Among them are biographies of the three first presidents of Iceland and he has also written a number of books about women, especially some who were ahead of their time regarding gender equality. The first volume of his biography about the poet Steinn Steinarr was nominated for the Icelandic Literature Prize in 2000. The latter was published a year later.

Gylfi Gröndal passed away on October 29, 2006.

From the Author

From Gylfi Gröndal

The first thing that came into my mind when I was asked to tell about my work as a writer, was how lucky I have been never to have been in doubt about what occupation to choose.

I started writing and creating fiction as a child, came into possession of an old Erica typewriter, made copies of little books and papers with chalk-paper and sold to the family members. I however soon found out that my decision to become a writer and poet did not go across well in my family. My grandmother on my mother’s side, Rannveig Hálfdanardóttir, sometimes paid us a visit in my childhood home, a woman from the west, Flateyri in Önundarfjörður, with course features, loud and rowdy. I jumped when she slapped her thigh, laughed and shook her head so much that the tassel on her hat swung back and forth. “I am told you want to become a poet, dear”, she ones said to me. “But the thing is, such harsh misfortune comes with it.” She then sighed heavily and added: “Well, you get it from your father’s side, lad. Such nonsense does not exist in my family.”

At good moments, all Icelanders want to be poets, and a poetic streak can be found in fairly many families in this country. But my grandmother was right about my father’s side, the need to write has been unusually persistent. I am told I am the sixth generation that publishes poetry. And even though the first three are counted with the national poets, and the next three among the smaller fish, the passion is the same and the spell that comes with it.

Even though we take our hats politely off for authors, if they are long since dead or have received prizes abroad, my grandmother’s view still dwells with us. My friend, Björn from Löngumýri, once said to me, most likely teasing me as he often did: “It isn’t difficult to be a writer. Writers sit down at their desks, take out the pen and then just lie and lie as much as they want to. And then they expect people to enjoy reading this bloody nonsense. Most writers are good for nothing, they just want to be provided for by the state, they are parasites.”

In spite of pessimistic forecasts and doubt, I kept going and had my best years while studying at Menntaskólinn í Reykjavík, where literature was higly regarded and school poets were considered a neccessity. Three people from my year tried to devote their lives to literature, as much as their situation allowed. In addition to myself those were the critic Ólafur Jónsson and the poet Dagur Sigurðarson. Both have now passed away, at much too young of an age, and in light of that it is not without pain that I remember those long lost days. Icelandic poetry was undergoing some difficult changes in these years. The debate about the “atom poets” was at its peak, one of the most heated literary debates ever in this country. As young and daring men, the three of us were bound to be on the side of the atom poets, there was no question about that. But it wasn’t easy, not many people spoke in their favor and they had to suffer both scorn and defamation as often is the case with pioneers.

I can still vividly recall the surprise and anticipation that got hold of me when I read two new poetry books my father had bought from young atom poets at Cafe Hressingarskálinn. They were Dymbilvika [Holy Week] by Hannes Sigfússon and Svartálfadans [Dance of Black Elves] by Stefán Hörður Grímsson, published in 1949 and 1951, when I was thirteen and fifteen years old. Later, I read Þorpið [The Village] by Jón úr Vör, published in 1946, Mitt andlit og þitt [My Face and Yours] by Jón Óskar in 1953, Eitt kvöld í júní [One Night in June], free impressions by Einar Bragi in 1950 and the first poetry book by Sigfús Daðason, Ljóð 1947-1953 [Poems 1947-1953]. Ólafur Jónsson could not afford to buy Sigfús’ book but his interest was such that he went to the National Library and copied the whole book in writing.

These books all played a roll in creating a new era in Icelandic poetry and are valued as such pioneer work today. But they were not published in many copies, most often by the author himself, read by a few at start and for quite long in fact. Then Hannes Pétursson appeared, like an angel of mercy; he combined old and new and gained attention by the general public from the start. Least of all I would want to belittle Hannes, he is one of the greatest poets of our times, but his success at the start cast quite a shadow on the atom poets.

While this debate was at it’s peak, a special meeting to discuss this issue was held in a school building in Reykjavík, probably at the end of 1951. There, Dagur Sigurðarson stood up, or rather Dagur Thoroddsen as was his name at the time, dressed in a sailors sweater with a scarf around his neck, in high and far too big boots, smirked and started his speach with these words: “Some think they can become poets by not cutting their hair and growing a beard. This is of course a great misunderstanding. They also have to give up cleaning themselves!” This was the typical Dagur and the sarcasism and pranksterness that later characterized his work.

The absurd and harsh argument about free and bound poetry was perhaps unavoidable. Without doubt the so called revolution of form enriched Icelandic poetry and did it good. Maybe people have never written better poems in Iceland than precisely in the latter part of the twentieth century. I myself find it particularly enjoyable how much diversity there is in our poetry today: obscure signs and complex images, simple narrative poems about every day issues – and everything in between. But in one sense, and a fairly important one, the debate about atom poetry hurt Icelandic poetry; it disconnected it from the public and it has never become the same as regards circulation.

All of a sudden the worryfree and poetic school years were over and reality looked you in the face. On the side of my Icelandic studies at The University of Iceland, I became a journalist in order to at least be able to sit in front of a typewriter and do some kind of writing. And I turned out not to regret that. Journalism is one of the most interesting jobs imaginable for a young and curious person. It also helped that at this time, around 1960, journalism was a growing field with golden and tempting opportunities everywhere. I became the editor of Fálkinn, an old and dignified weekly paper, at the age of 24, and at 28 I had become editor of Alþýðublaðið, one of Reykjavík’s newspapers.

Interviews were in vogue at this time and have been ever since. Valtýr Stefánsson, the editor of Morgunblaðið, and Vilhjálmur S. Vilhjálmsson at Alþýðublaðið are pioneers of the interview form here in Iceland, but the first interview book was written by Matthías Johannessen, poet and editor of Morgunblaðið. The title was Í kompaníi við allífið and it contained lively interviews with master Þórbergur Þórðarson. I went in the footsteps of Matthías and wrote an interview book with Kristinn Guðmundsson, foreign minister and ambassador. Kristinn was an extremely interesting man; always in a good mood, cheery and with a good sense of humour. He was an educated man of the world and his humour was most often refined and subtle. The book was very well received; it sold well and got good reviews. Thus, the flow had begun. Since then I have published a book almost every fall, both interview books and biographies – and sneaked in some poetry collections in between.

With the interview books it can be said that a new form of writing began in this country. Some people think it is not difficult to write such a book; you just tape the interviews and then write what is on the tape. But it is far from this simple. The difference between written and spoken language is so great that a spoken narrative cannot pass on book, no matter how good the narrator is. This is where the writer comes in, he has to form the narrative flow; dress it in language and style so that it comes alive on print. Here he has to situate himself on the line between spoken and written language; for it is much harder to write a simple, to-the-point and readable text than to pile up decorative words in a ceremonial style.

I was a journalist for thirty years, but wrote books in my spare time. The last ten of these I was the editor of Samvinnan journal and also worked at the educational department of S.Í.S. corporation. When that corporation collasped and many decent fellows were left unemployed, most people said to me – to my great pleasure: “You don’t have to worry. You will make your hobby your main job and devote yourself to writing.”

Everyone who writes in their spare time dreams of being able to devote themselves to writing and earn a living from it. But dreams are such that they should really not come true. It would never have occured to me to become a full time writer at the time, had I known what a lonely profession it is – and how difficult it is to earn a living from it. The change is drastic for a man who has had his monthly wages all his life and received numerous benefits; all of a sudden not to get any pension benefits, no summer vacation, no sick days, and literally nothing that the labour unions have brought about by their long and hard struggle. Even if my books have often sold well and been on best seller lists. They however do not always sell well; the copies sold swing from 700 to 7000, and the only salary the author gets is percents of the sale and thus he is at the mercy of the cruel laws of the market.

Apart from the uncertainty and risk, in the past few years I have been unlucky enough to be writing in difficult times for the Icelandic book publishing world. These have been meager years, putting some old and bold publishers out of buseness. But it is boring to listen to complaints. The book will live; it will not be killed by visual culture and images as many have predicted. Books can still be sold, if they are good enough and interesting enough. Some authors are blessed with a six month writer’s salary [from the Icelandic state; transl.] or even as much as three years. And I continue to write poetry and biographies – thank’s to my westborn stubbornness.

I have often been asked, with a mixture of astonishement and shock, how I can sit time in and out with men and women who are nearing the end of their lives. The answer is simple: I like it. In additon, I believe that inteview books and biographies have a historical purpose and will be of great use in the future. They contain the lives of our forefathers and –mothers, valuable narratives from a time that has passed and never comes back.

I try to choose good storytellers; strong personalities; people who are forward, have courage and grace; people who have not let any struggle make them smaller; women such as midwife Helga M. Níelsdóttir, union leader Jóhanna Egilsdóttir or Þórbergur’s Mammagagga [wife of writer Þórbergur Þórðarson, transl.] – and men like sea captain Eiríkur or my Björn at Langamýri.

I have made a point of writing about women who were ahead of their time as regards equality issues, for instance the painter Ásta who was the first Icelandic woman to finish a trade education, Hulda Jakobsdóttir, the first woman to become a mayor, not to mention Helga M. Nielsdóttir who was a midwife. She was the first woman who was assigned a building lot in Reykjavík, this was when she built the maternity hospital Fæðingarheimilið, later she also built a big residential house at Miklabraut. She delivered 3800 children in Reykjavík and in order to make it quickly between places, she bought a motorcycle that took her around town. It is also an experience that will not be forgotten to sit with Jóhanna Egilsdóttir in her very old age and listen to her talk about the struggle of the Icelandic working class when it rose up and demanded its rights.

Perhaps Mammagagga was the strongest and most memorable of the women I have written about. After her book had been published, a group of militant female litery scholars sat themselves in the judge’s seat and looked down on both of us, as if we were pitiful criminals. At this occasion Mammagagga said to me: “I am told this girl is fresh. But you can tell her from me that I am a thousand times more fresh. In addition I also have some magical powers, so she should watch out!” At that moment it became more clear to me than before how valuable it was for Þórbergur to have such a General by his side – in the battlefield of envy and obstinacy that Icelandic literary life can sometimes be.

All in all, I consider myself to have been privileged by fortune, having gotten to know so many people and such different ones so closely, their situation and conditons, their world views, lifes and fate.

Happiest I am for having been able to finish, at last, the biography of poet Steinn Steinarr – and thus to combine the rebellion and promise of youth with the bourgois work of adulthood.

It warmed my old soal.

Gylfi Gröndal, 2003.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

To Write About an Emotion: On the Poet Gylfi Gröndal

Briefly about the poet

When one looks at Gylfi Gröndal´s career as a poet, it is interesting how late in his life his first book of poetry, Náttfiðrildi (Night Butterflies, 1975), came out; in light of the fact that Gylfi was considered a promising poet in his younger years, and had his poems published in Ljóð ungra skálda (Poems by Young Poets,1954) and in Árbók skálda (Poets´ Yearbook,1956). In addition to that, his poems appeared regularly in school papers and literary magazines. Hence it would have been only natural that he devoted himself entirely to writing poetry, like his high school friend Dagur Sigurðarson (1937-1994) did.

In some ways however, he did. Not in terms of poetry writing, but having devoted most of his life to writing. Firstly, one should mention that he worked for over thirty years as a journalist and chief editor of newspapers and magazines like Fálkinn, Alþýðublaðið, Vikan and Samvinnan. On top of that, he has been one of the most prolific writers of biographies and interview books, with over thirty of them to his name.

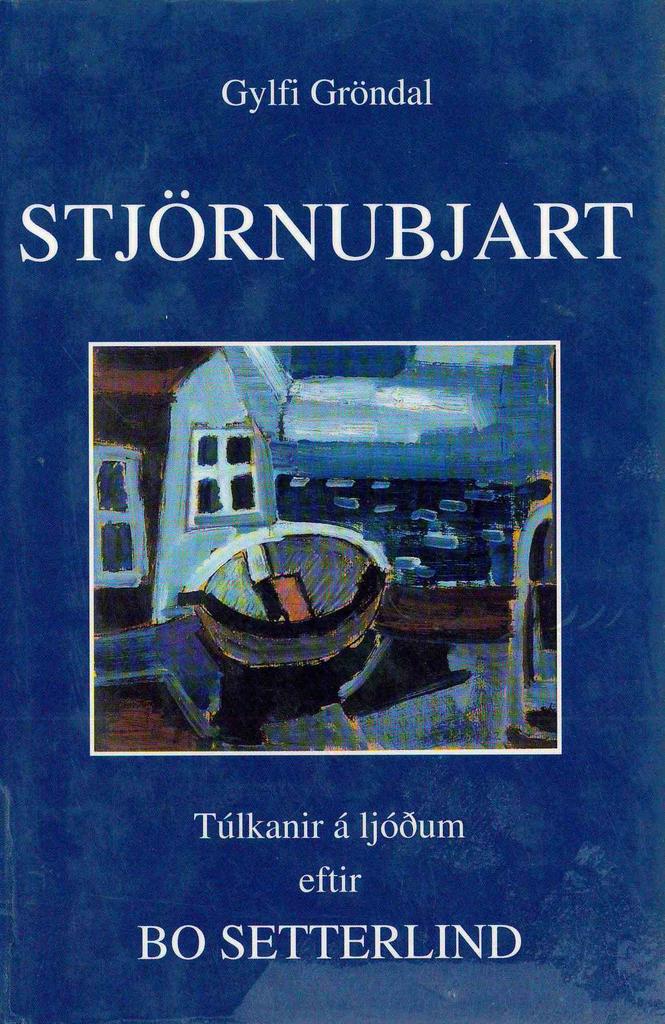

Poetry has not been a prominent part of Gylfi´s published works, and he can first and foremost be called a biographer and an interviewer. However, from 1986, when the magazine Samvinnan, which Gylfi edited, stopped coming out, he devoted himself solely to writing books. Since then, he has been a prolific writer and published many works. Among them are two books of poetry: Eilíft andartak (An Eternal Moment, 1986) and Undir hælinn lagt (Hanging in the Balance, 1996). Gylfi also translated, or rather interpreted, according to himself (see Þröstur Helgason: “Ljósið það er til.”Mbl. 23rd. January 1998), a selection of poems by the Swedish poet Bo Setterlind. They appeared in 1997, in the book Stjörnubjart (Starlight).

As well as the aforementioned books Gylfi has published the poetry books Draumljóð um vetur (Dream Poems in Winter,1978), Döggslóð (Dew Track, 1979) and Hernámsljóð (Occupation Poems, 1983). [After this article was written, Gylfi’s last book of poems came out in 2005, Eitt vor enn (One More Spring). Ed.]

Despite the fact that Gylfi is not as well known for his poetry as for his other works, it is clear that he is passionate about it. This was confirmed in an interview with Súsanna Svavarsdóttir in 1990, in which he says that poetry writing is an “incurable passion” of his and although he did not publish a poetry book until he was thirty-eight years old, he had always written poems. (“Perhaps it is a blessing that one´s dreams do not come true.” Súsanna Svavarsdóttir´s interview with Gylfi Gröndal. Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 26th May, 1990.)

As a young man, Gylfi admired the so-called atomic poets and looked up to poets like Hannes Sigfússon, Stefán Hörður Grímsson, Jón úr vör, Einar Bragi and Jón Óskar, and last but not least Hannes Pétursson and Steinn Steinarr. Gylfi also wrote the biography of the latter, Leit að ævi skálds (A Search for the Life of a Poet), which came out in two volumes in 2000 and 2001. For the first one he was nominated for the Icelandic Literature Prize. Gylfi believes that in this work he managed to “combine [...] the rebelliousness and promise of youth and the bourgeois work of adulthood” as he says in a short essay published on this website.

When Gylfi began to publish poetry books there was not the same kind of revolution in the air as there was when he was young. His poems can also hardly be considered highly original or rebellious. Although Gylfi is in many ways a pioneer in interview book and biography writing, having written about many curious characters, a break with tradition can not be said to characterise his works. He is thus the polar opposite of his fellow poet and schoolmate Dagur Sigurðarson, who made it his mission to go against the universal and the accepted, as Gylfi interprets it in his memorial poem “Auðlegð” (“Riches”) (Undir hælinn lagt).

Hrakningsárin

eru loks liðin

hin langa útlegð

á götum smáborgarannaæskan ríkir ein

með auðlegð sína

og staðfestuhlutabréf í sólarlaginu

miljónaævintýrið

kokhreysti á kaffihúsum

og stráksleg ögrunþína skál, ó minning

sem starir á mig.[The vagrant years

are over at last

the long exile

in the streets of the petite bourgeoisieyouth rules alone

with its riches

and steadfastnessa stock option in the sunset

the million dollar adventure

cockiness in cafés

and boyish defianceto you, oh memory

who stares at me.]

What, then, are the characteristics of Gylfi´s poetry?

Briefly About the Poetry

If one was to describe his poems in a brief, complete and compressed way, the most obvious term to use would be “introverted”. “Introverted” in the sense, that they convey emotions which have been awakened within the poet or the poetic “I”. Alone, this description is not worth much, of course, as it could apply to any poet, although it does make a distinction between a poet who is socially aware and a poet who tries to express his/her personal feelings. To go further and explore what possibly distinguishes Gylfi from other poets, it is best to begin with the basis which Gylfi himself mentions as a characteristic of his poems: a memory of an emotion. (See the aforementioned interview with Súsanna Svavarsdóttir).

In order to better explain what a memory of an emotion means, it is worth referring back to Gylfi´s own words where he says that his poems are based on life experiences. However, as the meaning of the term “life experience” is quite broad, I will try to narrow it down. One is not talking here about conveying anything “big” in the most dramatic sense of the word, on the contrary. It is something small, something which normally remains unnoticed, something which is ordinary, something which generally does not leave large footprints in one´s soul, yet is a part of the life experience. This is the emotion part. The memory part contains something which is remembered. And memory often proves fallible. So, when memory and emotion go together, it creates an ambiguous realm which is based on something which most people go through without staying there. This is where Gylfi pauses.

Minning

Daglega kveiki ég

á myndbandi hugans

og sé þig ljóslifandi.Allt birtist mér

á skjánum í einni sjónhendingu:andartakið

sem þú dvaldir hérog eilífðin

síðan þú kvaddir.(Gylfi Gröndal 1986:19)

[A Memory

Daily I switch on

the video tape of my mind

and picture you vividly.

Everything appears in front of me

on the screen in an instant:the moment

you stayed here

and the eternity

since you said goodbye.]

Gylfi certainly uses various methods to evoke this basis. There are however a few elements which dominate and appear again and again in his poems. One is nature. From the start, nature has been a big part of his poetry. Gylfi normally uses nature to reflect some emotion. “Some” is the operative term here, as this emotion is more often than not ambiguous; something which can not be fully captured; not unlike people´s experience of the beauty of nature perhaps is. A good example of this interplay between nature and emotion can be found in the poem “Lögberg”, which appeared in Árbók skálda in 1956:

Ég stóð einn. Þungt regn

og þaut í vindi

á fornri slóð.

En kennd: björt, hrein og helg

um hugann streymdi-Ég stóð þar einn. Og þá

var sem ég fyndi

í fjarska, nið

orð

ljóðljóðið um það sem Jónas forðum dreymdi.

( Gylfi Gröndal 1956: 66)

[I stood alone. A heavy rain

and whispering wind

on an ancient track.

An emotion: bright, clean and holy

through my mind flowed-I stood there alone. And then

it was as if I felt

from afar, a hum

a word

a poemthe poem about that which Jónas dreamt of old.]

Here, nature literally awakens an emotion, as if the poetic “I” senses something without being able to explain it better than that it is the “poem which Jónas dreamt of old”. Indeed, the poem is meant to convey intangibility. This poem also has an indicator of another characteristic of Gylfi´s poems which might be called a gateway or a limbo of poems...

A great number of his poems address the difficulties of writing when no poem is produced; poems about a poem which does not get made, or some kind of a limbo. In “Lögberg” this consists of speaking of a poem without going into it any further, although it is a poem the poet Jónas (Hallgrímsson) dreamt. The best example of a limbo poem is perhaps the poem “Ekki er ort” (“No poem gets written”) (Undir hælinn lagt):

Gömlu gráu heilasellur

hvað líður ljóðinu dýra

eftir langa ævi

og iðkun málssvala klakar við glugga

og ekki ert ortum orðin berjast

blíðmæli og eldtungaekki er ort

og höfuð mitt að veðienn er þó von bjargvættar

að bægja frá hamhleypuhvítir vængir

og náhljóð

í næturkyrrð.[Old grey brain cells

what of the great poem

after a long life

and practice of languagecooling ice at window

and no poem gets writtenbattling over the words

are sweet language and a tongue of fireno poem gets written

and my head at stakeStill there is hope of a rescuer

to fend off a berserkerwhite wings

and sounds of death

in the stillness of night.]

Although Gylfi´s poems mainly refer to an inner world, they also have one characteristic which refers to outside elements. If one was to give it a name, it would a “poetic image album” or a “poetic scrapbook”. The poetic image album conjures an image of a particular place (for instance New York, Miami, Paris, Rhodes and others), describing it with an interplay of the features of the place and the emotions it invokes in the breast of the poetic “I”.

Dagljóð frá Rhódos

1

Ljóð vitja mín

með strengleik

orðvana laglínurhve hlýtt er

mitt kulvísa hjartahér er stundartöf

og staðleysatilfinning

einkennileg.[A Day Poem from Rhodes

1

Poems visit me

with music

speechless lines of a songhow warm is

my chill-prone hearthere is a short pause

and a limboa peculiar

emotion.]

The “album” could also include Gylfi´s memoir poems. One poem from this category is “Hernámsljóð” (“Occupation Poem”), a poem in thirteen parts from a book with the same title, about a child´s experience of the occupation years where “The army trucks” are “brown monsters/ with fangs on wheels"(46), “Granny comes from the west country/at the start of winter /to die” (51), “soldiers lead /the daughters of Iceland in dance” (48) and “The nation becomes free [...]/with war profit in our hearts” (58). Other poems also fall under this definition without being memoir poems. The chapter “Við hirð konungs” (“At the King´s Court”)(Döggslóð), which tells of events and characters in the Icelandic Sagas, fits nicely. These poems are in some ways more tactile than other poems by Gylfi, for instance this one, in the first part of “Hernámsljóð” : “A house with a red roof / [...] /gleaming white in a green meadow”. (Gylfi Gröndal 1983:39)

Finally, in listing Gylfi´s authorial traits, one should mention what could be called “heightened everyday images”. It means that the everyday is given an extra significance by linking it to something mysterious or by viewing it in a fresh light; making it unfamiliar. This can both apply to everyday things in general, as well as the poetic “I”´s everyday things: the way home, driving, writing and looking at nature or at buildings. In the poem “Í stofunni” (“In the Sitting Room”) (Eilíft andartak), an everyday activity like watching television is equalled with “living and living/and yet not living” (Gylfi Gröndal 1983:33) (letting television live your life for you). A different picture is thus painted of the act of watching television.

In terms of formal characteristics it is worth pointing out that many of Gylfi´s poems border, one could say, on being alliterative verse. He uses this form up to a certain point to emphasise rhythm and lyricism. Such a method recalls the poems of Hannes Pétursson, who is considered the first poet to combine the old form, with its requisite alliteration, with modern atomic poetry. It is also worth mentioning that Gylfi often uses fairly traditional nature images (summer: fertility of the spirit and winter: the opposite).

Certain characteristics or themes of Gylfi´s poetry have been mentioned here separately. More commonly however, they are mixed together. Of course one can endlessly find new angles and approaches. Not all of Gylfi´s poems fall comfortably under this definition, either. Nonetheless, it creates a framework which one can work within when analysing his poems.

Briefly on Gylfi´s Poetry Books

As mentioned before, Gylfi´s first book, Náttfiðrildi, came out when he was thirty-nine years old. At that time he had not produced a poem for publication for a long time. It is therefore fitting that the first poem of the book is entitled “Af stað” (“Taking Off”) as a kind of a symbol of a new beginning. Náttfiðrildi has all the characteristics which were listed here earlier and is perhaps the book which is best suited for exploring Gylfi´s poetry with those in mind. It contains poems which show how emotions blend into nature, and nature is used to describe the difficulties inherent in writing, and describing everyday environment in a fresh way.

In Draumljóð um vetur, the poems have become more specific, with a theme that runs trough them, that of the books title. In short, their theme is the doldrums of winter and the hope, that the spirit will soar at the onset of spring. The poems work themselves away from the cold towards a gradual thaw, or the point “when a sun rises over a silent everyday city” (Gylfi Gröndal 1978:77)

In Döggslóð his poetry becomes more tactile, with poems about characters from the Icelandic Sagas and poetic places like Arnarfell, Ireland and Thingvellir.

One should also mention the chapter “Hljómsveit götunnar” (“Orchestra of the Street”), where general street life is described in an almost glorified way or pulled out of it´s everyday perception, as in the poem “Á götunni” (In the street), where heels that “click on pavement slabs” are likened to musical instruments “in the orchestra of the street”. (Gylfi Gröndal 1979:31)

Hernámsljóð contains, in my opinion, some of the best in Gylfi´s writing. That goes especially for the title poem, where an adult poetic “I” remembers his youth in the occupation years and remembers that “there once was here/the world of a child/[...] [which] lives and grows/in a small corner of the mind/On and on”. (Gylfi Gröndal 1983:60-61) Gylfi´s also continues here with the so-called poetic image album and conjures images of more places, as in “Grænlandsljóð” (Greenland Poem): “Icebergs in Eiriksfjord/chalk white in the distance/on sailing closer/the icebergs turn out to be/blue-clear/in bright sunshine”. (Gylfi Gröndal 1983:29)

Eilíft andartak is more concerned with the so-called “gateway” than the previous books. The poetic “I” requests for instance a mental note in an eponymous poem from the great sender, because his mind is “a/white sheet of paper/” awaiting him. (Gylfi Gröndal 1986:11) The book also contains his translations of poems by other Nordic poets, including Olav H, Hauge, Anders Apelqvist, Solveig von Schoultz and Bo Setterlind. Theirs and Gylfi´s poems are in a similar vein. Setterlind´s poems in particular are similar to his in their natural simplicity and lyricism.

The book Undir hælinn lagt was published on the occasion of Gylfi´s sixtieth birthday. Here he continues to work with the same themes as before, reaching, as is the case with people who are ambitious about their work, more and more skill. It also contains Gylfi´s translations of the poems of a few poets. They include Bo Setterlind and the Nobel prize-winning poet Oktavio Paz.

Briefly at Last

Most of Gylfi´s poems are plain, un-dramatic and contain many references to nature. They are meant to convey the experience of the mundane, which rages within people, although the cannot find channels to put this emotion into words. Gylfi does, however, and he also conjures more specific images of places and memories... If there is something which can safely be said about his poetry, it is that he writes about emotion/s with emotion ...

© Ólafur Guðsteinn Kristjánsson, 2005.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Bibliography:

Gylfi Gröndal. 1956. “Lögberg.” Árbók skálda. Helgarfell, Reykjavík. P. 66.

___________. 1975. .Náttfiðrildi. Setberg, Reykjavík.

___________. 1978. Draumljóð um vetur. Skáprent, Reykjavík.

___________. 1979. Döggslóð. Fjölva útgáfa, Reykjavík.

___________. 1983. Hernámsljóð. Setberg, Reykjavík.

___________. 1990. “Kannski er það kostur að draumar manns rætist ekki.” Súsanna

Svavarsdóttir´s interview with Gylfi Gröndal. Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 26. May. Taken from

the archives of Morgunblaðið at www.mbl.is.

___________. 1996. Undir hælinn lagt. Forlagið, Reykjavík.

Þröstur Helgason. 1998. “Ljósið það er til.” A review of Stjörnubjart. Morgunblaðið 23. January. Taken from the archives of Morgunblaðið at www.mbl.is.

Awards

Nominations

2000 - The Icelandic Literature Prize (for non fiction works): Steinn Steinarr: In Search of the Life of the Poet

Á vængjum söngsins: Jóhann Ingimundarson segir frá (On the Wings of Song)

Read more

Eitt vor enn (One More Spring)

Read more

Fólk í fjötrum : baráttusaga íslenskrar alþýðu (A People Bound: A History of Working-Class Struggle in Iceland)

Read moreSteinn Steinarr: Leit að ævi skálds II (Steinn Steinarr: In Search of the Life of the Poet II)

Read more

Steinn Steinarr : Leit að ævi skálds (Steinn Steinarr: In Search of the Life of the Poet)

Read more

Saga athafnaskálds (The Story of an Entrepreneur)

Read more

Að breyta mjólk í mat (Turning Milk into Food)

Read more

Íslensk veitingasaga II (A History of the Icelandic Hospitality Business II)

Read more

Undir hælinn lagt (Under the Heel)

Read more