Bio

Lilja Sigurðardóttir was born in 1972. She studied pedagogy and education at the University of Iceland where she completed her B.A. degree. She has worked as a specialist in the field of education and edited school books for preschool. She is now a full-time writer.

Lilja's debut, the crime story Spor, was published in 2009 and well received. A year later she published her next story. In 2015, the first story of her trilogy, Gildran, (Snare) was published which became very popular among both Icelandic readers and publishers abroad. The second book of the trilogy, Netið (Trap), followed the next year and in 2017 the last book, Búrið, (Cage), was released. The books have now been translated and published in many countries.

In addition to writing thriller stories, Lilja has worked on screenwriting for television and written plays. Her play The Big Kids was staged by the theater company Lab-Loki and ran during the winter of 2012–2013. It received the Gríma Award as a play of the year 2014. In 2018, Gildran was nominated for the CWA Daggar Awared, an award from the British Crime Writers Association.

In 2018 and 2019 Lilja received The Drop of Blood, an Icelandic crime fiction prize, and in 2023 the Storytel Awards for the best audio series for One hundred Mishaps of Hemingway. The same year she was appointed Kópavogur City Artist.

About the Author

“That wouldn‘t happen in Iceland” – The Thrillers of Lilja Sigurðardóttir

In Lilja Sigurðardóttir’s first crime novel, Steps (Spor, 2009), a man is blown to pieces in the middle of Austurvöllur – a public square in the centre of Reykjavík. Upon the book’s publication in 2009, it is more than likely that some readers may have shaken their heads at this scene and grumbled: “That wouldn’t happen in Iceland.” In fact, you could say that from the very beginning, Lilja has tried to flaunt the conventions set by the Icelandic crime thriller’s forerunner, the Scandinavian noir novel, which has one foot firmly planted in gritty Nordic realism. In her books, Lilja tackles international drug syndicates and business conspiracies. These are crimes of a totally different scale than what Inspector Erlendur refers to as a “typical, Icelandic murder” in Arnaldur Indriðason’s Jar City (2000), which set the tone for the emergence of Icelandic crime fiction. Lilja published a second crime novel, Forgiveness (Fyrirgefning, 2010), featuring the same main characters the following year, but then turned her attention to writing for the theatre. She received the Icelandic performing arts prize Gríman for her play The Big Kids, staged by theatre company Lab-Loki in the winter of 2013-2014. In 2015, she returned to crime fiction with the publication of Snare (Gildran), the first instalment in a trilogy of novels about star-crossed lovers Agla and Sonja. Since then, Lilja has delivered a new crime thriller every year.

It seems as if Lilja trusts her readers to suspend their disbelief against anything she might throw at them. In her books you can find serial killers and cults, man-eating tigers, witches and folklore. Her protagonists are not members of the police force but ordinary (or extraordinary) citizens who are dragged unwillingly into the action or are in cahoots with the criminals themselves. Her protagonists’ morals often take centre stage as the characters make unwise or duplicitous decisions and may even morph from ordinary people into cold-hearted criminals. At times, they try to justify their actions on the basis of protecting their loved ones, but often there is no less conflict to be found within these familial or romantic relationships. Addiction is also a recurring theme in Lilja’s books, whether it’s addiction to drugs and alcohol or addiction to love and power. As such, happy endings are rare in Lilja’s fiction, but you might say that at the end of each book the characters find their path – or at least stop trying to fight their true nature.

Steps

In Steps, her first book, Lilja doesn’t make do with just one or two murders. Her sleuth, Magni, is a recovering alcoholic who earns his living translating romance novels. Magni is actually on the hunt for a psychotic killer who murders his victims in evermore creative ways; the first Icelandic serial killer since the execution of 16th century murderer Axlar-Björn.

In many ways, Magni is the perfect example of a protagonists à la Lilja: He gets dragged into the investigation unwillingly, is haunted by personal demons and has burnt many a bridge behind him. At the start of the book, he has resolved to become a new man, has just returned from rehab and intends to stick to the straight and narrow with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous and their Twelve-Step program. However, his plans are put in turmoil when his ex-wife, police inspector Iðunn, asks him to keep his eyes open during AA-meetings as the murders she is investigating seem to have a link to Alcoholics Anonymous. Despite having his hands full keeping Bacchus at bay, Magni agrees to help her, hoping to prove to Iðunn that he is a changed man. Soon, the two of them are on the killer’s trail and the bodies start piling up.

Steps makes good use of its succinct structure. The book consists of 12 chapters, each of which bears the title of one of the twelve steps that members of Alcoholics Anonymous must take in the hope of overcoming their addiction. Thus, each chapter follows a theme that leads Magni through his inner journey while also leading him towards revealing the identity of the killer. The book’s depiction of AA’s culture and philosophy, as well as the everyday realities of active or recovering alcoholics, shows signs of significant research and makes for a strong setting. This realistic basis works as a counterweight to the somewhat gratuitous violence and implausible plot. A similar counterweight can be found in Magni’s ongoing recovery; he tries to stick to a strict and healthy routine that consists of visits to his local swimming pool, adequate sleep and a healthy diet to avoid any confrontations or surprises that might drive him to drink. These routines ground the narrative within the humdrum of the everyday until Lilja’s blows it all to smithereens – literally.

Forgiveness

Forgiveness, Lilja’s second book about Magni, takes place seven months after the events in Steps. He and Iðunn are expecting a child after a fateful one-night stand in the previous book, and Iðunn has moved in with Magni so that he can support her during the pregnancy. Magni still holds out hope that the two of them will get back together, although he also finds himself drawn to Fríða, a young woman who he met in an AA-meeting and with whom he had a brief fling previously.

As a recovering alcoholic trying to stick to the straight and narrow, Magni continues to be confronted with various challenges. His desire to lose himself at the bottom of a bottle is never far away, and now he is also afflicted with post-traumatic stress disorder from the events of the last book. To overcome his trauma, he decides to take a break from translating romance novels and reawaken his old dream of becoming a writer. The book that he intends to write is a book of interviews where he speaks with other victims of violence about their experience and their recovery. Just as Steps’ structure is modelled on the Twelve-Step program, in Forgiveness Lilja uses the book that Magni is in the midst of writing to drive the narrative. Chapters are named after the survivors that Magni interviews and are even accompanied by Magni’s own forewords, where he introduces the interview subjects and briefly covers their trauma history. Lilja’s takes this meta-textual game even further with Magni deciding to title his book Forgiveness and pondering whether to write the story of his own trauma and publishing it with the title Steps. However, when Magni starts asking about the perpetrators of the violence inflicted on his interview subjects, he finds that all of them have recently met with fates that are suspiciously reminiscent of the crimes they committed and the trauma they inflicted.

As in Lilja’s previous book, Forgiveness makes use of psychological and therapeutic knowledge to establish a realistic grounding for the story. However, although Magni is still struggling to stay sober, this second book is more concerned with his PTSD than his alcoholism. While he tries to overcome his anger, he forges a bond with the other survivors in his support group, especially Fríða who is also one of the victims of the events in the first book and has the scars to show for it. Several more characters from Steps also make an appearance, so that it feels a bit strange to refer to the book as an independent sequel. Crime authors usually avoid referencing their previous books in detail, even when the books are all a part of the same series. That way, new readers can make their start anywhere in the series without worrying about ruining the enjoyment they might get from seeking out the author’s earlier books. It is clear that Lilja intends for the books about Magni to be read in the right order, same as her next series, the trilogy about Agla and Sonja. This is evident in how she makes no attempt to hide or gloss over the identity of the killer in the first book – which I will refrain from doing here.

Snare

In her introduction here on the web, Lilja refers to her first two books as “mysteries” – as opposed to the books that have followed annually since 2015, when Snare, the first book about Agla and Sonja, was published. Regarding this transition, she writes: “In Snare, I decided to try a new genre and write in the style of the thriller. I soon realised that by doing so, I had truly found my place.” So it is no wonder that in the first few pages of Snare, the reader can detect a significant change in her writing style. For one, Steps and Forgiveness are both written in a first-person present-tense – as used by private detective novels in the tradition of Raymond Chandler. Magni is the novels’ narrator and directly transcribes the events to the reader. Scenes are limited to Magni’s presence on the page and the reader is subject to the limited amount of information that Magni can provide. Snare, on the other hand, is written in a traditional third-person past-tense. The perspective is much freer and moves at some pace between a handful of key characters in brief chapters. This setup would come to define Lilja’s writing style: short chapters and a group of key characters who are in minimal contact and move separately through the narrative. It’s a drastic change from her previous books, as can be seen in the fact that while her first two books fall between 11-12 chapters, her later books change perspectives so often that they habitually contain more than a hundred chapters.

In Snare, the plot is revealed from the point of view of four different characters: Sonja, a seemingly respectable middle-aged woman who is actually a major drug mule; her young son Tómas; her lover Agla, a banker with shady morals; and Bragi, an aging customs agent. In severe financial straits after an ugly divorce, Sonja finds herself smuggling illegal substances into Iceland on behalf of drug lords who have total control over her fate and send her on ever more dangerous jobs. She justifies her illicit activities with a dream of regaining custody of Tómas and making a home for the two of them, as he lives with his father in Akranes, a town just outside Reykjavík, and rarely gets to see his mother.

While Sonja tries to save herself and her son from the Icelandic drug lords pulling her strings, her lover, Agla, is also struggling in a snare of her own. She is a banker and is under investigation for her part in putting the Icelandic economy in jeopardy during the gung-ho years leading up the country’s financial meltdown in 2008. Before the crash, she took part in a variety of questionable business deals that lined the pockets of millionaires, banksters and the so-called “expansion vikings” –Icelandic investors whose reckless overreach played a big part in the financial meltdown. She and Sonja are locked in a difficult and sporadic romantic relationship which mainly consists of Agla showing up at Sonja’s door late at night in a state of inebriation, as Agla has yet to accept her own sexual orientation.

The fourth key character is customs agent Bragi, an older man who leads a quiet life which mainly consists of visits to the care home where his wife resides. She suffers from final stages Alzheimer’s and doesn’t recognise him anymore, but still Bragi is eager to move her back into their home so they can spend her final days together. However, he lacks the finances to provide her with the home care that she needs. While keeping his supervisor at bay, who keeps hinting that it might be time for Bragi to retire and let a younger man take his place, Bragi starts taking an interest in a certain, respectable businesswoman who passes through the air terminal on her frequent trips abroad.

Shortly after the reader first meets Sonja, she spies a young woman which she deems capable of helping her smuggle her shipment into Iceland.

The young lady hadn’t done anything to her. Under normal circumstances, Sonja might have killed some time chit-chatting with her. But it was no use feeling guilty, the woman fit her plan perfectly. (8)

These chilling words set the tone for how the trilogy’s main characters (aside from young Tómas) seem able to dismiss all moral concerns regarding the consequences of their actions and use a variety of justifications to stifle their sense of guilt and sympathy. Even Bragi, who initially appears as a representative of law and order, doesn’t seem to be driven by anything other than a bureaucrat’s satisfaction with a job well done, and never ponders the fate or circumstances of the drug mules that he catches passing through customs with their bellies full of condom-wrapped narcotics. Sonja justifies her actions by telling herself that she has no choice, and that Tómas’s wellbeing is at stake. However, it is evident that she derives some pleasure in her abilities as a drug mule – or, as she continues on the next page:

When she first found herself in the snare, she’d feel guilty about how much she enjoyed her increased heart rate and the rush that followed, but by now she knew that the only way to do the job was to enjoy the thrill. (9)

Agla’s justifications for the market manipulations that she took part in before the collapse of the Icelandic banks are of a different nature. She has been living within the patriarchal world of bankers and financiers for too long, where she has had to be tougher and harder than her male co-workers in order to gain their respect. While being interviewed by the special prosecutor, she doesn’t hesitate to fess up to a variety of legal but morally repugnant financial dealings that she undertook on behalf of the bank. Speaking with María, a special prosecutor investigator who will have a larger role later in the series, she justifies her actions in the following manner:

Everybody was doing it ... It’s a recognised business model [...] It’s the circle of life ... You can’t change that. The big fish eats the little fish. That’s how it goes. (128)

Even though Sonja, Tómas, Agla and Bragi take turns leading the narrative, it is indisputably Sonja who is at the forefront in this first book. The main storyline revolves around her transformation from a single mother in financial straits into a ruthless femme fatale – a journey that will continue in the next two books. Sonja, who will protect herself and Tómas by any means necessary, shows just how far Lilja is willing to push the morality of her protagonists and how she trusts her readers to follow them all the way. For one, she doesn’t hesitate to let Sonja poison and murder one of the sniffer dogs used by the customs officers. In this, she breaks one of the main commandments of western popular culture: no matter what sorts of murders and violence a protagonist might commit they should always be kind to animals.

Trap

While the two Magni books might be heavily interconnected, the Agla and Sonja trilogy can almost be read as a single, massive crime thriller that spans more than 1000 pages. This is evident in the first book’s cliff-hanger ending, which shows Agla headed for prison for financial misdeeds and Sonja and Tómas on the run. At the start of Trap (Netið, 2016), the second book in the series, a mere two months have passed. Sonja and Tómas are in hiding in a trailer park in Florida, but in only a few pages they are back in the hands of the drug lords, who force Sonja to return to her old occupation. It turns out that Iceland, due to its unique location, is a mere midway point for the drug shipments on their way from one continent to the next. Sonja realises that the only way for her to escape the grasp of the Icelandic drug lords once and for all is to weaken their standing within the international crime syndicate overseeing the movement of the drug shipments from afar.

Sonja’s crimes remain in the background in this second book and Agla’s illegal financial dealings are given more attention than before. The special prosecutor has concluded their investigation of Agla’s role in the bank’s market manipulations before the financial meltdown. Before actually starting her sentence, she finally has the necessary breathing space to make sure that the funds she hid in offshore accounts for her co-conspirators are still safe and sound. That’s how the reader is finally introduced to Ingimar, “Iceland’s aluminium prince”, a seemingly above-board investor who actually has a hand in a variety of illegal operations and international conspiracies. “He was like a spider, his web could be found in the unlikeliest of places” (135), Agla thinks, as she sits on the couch in Ingimar’s Tjarnargata mansion, in the heart of Reykjavík.

Ingimar will become one of the key characters in Cage (Búrið, 2017), the third book in the trilogy, but here he remains in the background. However, Trap introduces a new main character who takes charge of one of the book’s storylines: María, the special prosecutor investigator mentioned above, who despite Agla’s sentence is not at all satisfied with the conclusion of the case. She is certain that Agla is protecting other key players. Much like the rest of the characters, María has a journey ahead. When we first meet her in Snare, she expresses her disgust with Agla’s conduct and perspective, but her hatred of white-collar criminals and her enthusiasm in her work will lead her into some difficult situations, and it turns out that she is willing to use unscrupulous methods in the cause of justice.

In the book, readers also get to know Agla better. Her backstory is revealed; her childhood as a tomboy and the shaping influence of her mother, who did her best to provide Agla with the means of standing up to her brothers:

“In life, a conscience is one of the main things that holds women back,” her mother had said. “If you let go of your conscience, you’ll be free.” [...] “Just look at your brothers ... they’re not bothered about conscience. They just forget and move on.” (100)

This lesson has stayed with Agla and served her well in the male-dominated world of banking. There, she has learned to play the game of high-risk finance just as well as the boys, even if they never accept her as an equal, but rather “gave every indication of bitter jealousies, as if she had taken something that rightfully belonged to them” (148). But despite having learned at a young age that a conscience is just for nice girls who never get their way, Agla is still tormented with guilt over her and Sonja’s affair, which caused the end of Sonja’s marriage – when Sonja’s husband Adam walked in on their lovemaking with Tómas in tow. Still, her guilt seems to have little to do with Adam himself, who revealed his true nature after his and Sonja’s divorce, but rather goes to something at her core:

Since then, everything to do with Sonja made her feel guilty, as well as something else; another feeling that had turned up with Sonja: Shame. (100)

This goes some way to explain her hesitance in accepting Sonja and their relationship; she feels utterly powerless when it comes to her feelings for Sonja but still dislikes it when Sonja uses the “L-word” to describe herself or Agla. Instead, she tries to dismiss their love affair as “ ... something to do with her hormones, maybe due to menopause” (Snare, 65).

When Sonja returns to Iceland, Agla feels as if she has been given one last chance and is determined not to lose her lover again due to her own insecurities and sense of shame. She does her best to set up a life for the three of them – herself, Sonja and Tómas – but it turns out that Sonja has gone too far and has been selling her soul in tiny little parts for too long. Now there is no escaping the person she has become:

Maybe it was time to stop trying to swim back to the surface. Maybe, she needed to let herself sink to the bottom, where she might find the foothold she needed to push back. (301)

Cage

In Cage, the final book in the trilogy, we meet Agla at the end of her tether, serving her sentence in Hólmsheiði prison. Sonja has again disappeared from her life, smashing all their dreams and leaving the house that Agla bought for them without any explanation. Again, Sonja’s story remains in the background, so that the reader doesn’t know what drove her to abandon Agla for once and for all. In her place, new and old characters step forth to fill the void.

María is back, having resigned from the special prosecutor’s office and become a sort of investigative reporter, running her own, independent media company called The Squirrel. With help from the paranoid-yet-well-informed Marteinn – or Voice of Truth, as he refers to himself – she intends to unveil Ingimar’s true, criminal persona. It is evident that María has now fully completed her transformation from a law-abiding civil servant, with her home and her relationship all in order, to a kind of hard-boiled detective figure, who is willing to do anything to get to the truth. Her eagerness to uncover the crimes that Ingimar and his co-conspirators are responsible for leads her to some unexpected places, especially when she and Agla discover that they share a mutual interest in Ingimar’s fate. Following this, Agla sends her all the way to the Midwest of the USA, on a mission to uncover the shady underbelly of Ingimar’s aluminium smelter empire.

Ingimar himself also steps forth as one of the key characters in the book. He comes off as a rather pitiable figure, one who readers might find themselves feeling an inkling of sympathy towards, despite his wealth and his many crimes. Readers are given an insight into the difficult home life within the walls of his Tjarnargata mansion, are introduced to his wife, who spends most of her day under the influence of tranquilisers and alcohol, and the dominatrix who he meets with on a regular basis for a whipping – to remind him that he is “just a man” (21). Finally, there is Ingimar’s son, Anton, who becomes another key character with a separate storyline.

On the surface, Anton seems like any other teenager, but much like his father he harbours a dark secret: stacks of dynamite that he has hidden in the basement of their Tjarnargata home. He is consumed by a radio station called Edda (a thinly veiled cover for the Icelandic conservative radio station Radio Saga) which spews out hate speech against immigrants and Muslims day in and day out. The dynamite hidden in the basement in Tjarnargata is a part of Anton’s plan for causing chaos within Iceland’s political landscape, although his reasons seem to mostly revolve around his obsession with his girlfriend, Júlía.

When Sonja finally re-enters the narrative in the second half of the book, she is a changed woman; no more the single mom who was unwillingly led into the world of drug smuggling in the first book. She and Agla share a brief reunion, where Agla finally manages to sever the emotional hold that her feelings for Sonja have had on her from their first meeting. Instead, she finds herself becoming attracted to Elísa, a young woman she meets while serving her sentence in Hólmsheiði Prison. Elísa is a recovering addict and former drug mule whose supervisors sent her into the open arms of Icelandic customs – much like other such decoys previously used to distract the law from Sonja’s frequent smuggling trips. In Elísa, Agla finally finds true happiness; a person capable of loving her back, one who she can tend to and take care of in a manner that Sonja never made available to her. But despite this newfound happiness and the humdrum of domestic life that seems to await the pair at the trilogy’s end, it is evident that Agla still has a take-no-prisoners attitude when it comes to money and finance – as we will see in her brief appearances in Lilja’s later books.

Betrayal

Having completed Agla and Sonja’s stories in Cage, you might think that Lilja would relish a fresh start. Even so, there are threads leading back to the trilogy in all her later books. This shows that, at least since the publication of Snare, all of Lilja’s fictions take place within the same world. She has created a large cast of characters who move freely between her books. This becomes evident when, Úrsúla, one of the main characters in Betrayal (Svik, 2018), Lilja’s first book after completing the trilogy, finds herself in the uncomfortable position of having to meet with Ingimar, who is now serving a sentence in Hólmsheiði Prison. Even so, he is seemingly still involved in various illegal activities, some of which might cause havoc for Úrsúla, who has just accepted the chair of the Minister to the Interior.

The timeline in Betrayal is much swifter than in the preceding trilogy. The whole story takes place in a single week, starting when Úrsúla is sworn into her role as a minister. She’s an idealist, has recently returned to Iceland after working as an aid worker in a refugee camp, and she means to make the most of her new position. This proves to be quite a challenge, as it turns out that the powers-that-be mean to use her as a pawn in their games of political chess. Úrsúla has to outsmart them while also battling the PTSD she suffers from after her experiences as an aid worker. She is supported by the personal driver provided to her by the ministry, the able-bodied Gunnar, who undertakes his work with much aplomb and considers himself more of a bodyguard than a driver. Thankfully so, as Úrsúla is soon receiving strange and alarming threats, online as well as scribbled on crumpled notes that she discovers on her person.

In addition to Gunnar and Úrsúla’s storyline, the book follows two seemingly unconnected characters: Pétur, a vagrant who roams the downtown area in a state of delusion and seems to fear that Úrsúla is in imminent danger from someone he simply refers to as “the devil”; and the Faroese Marita, a housewife married to a local police officer in Selfoss, a town near Reykjavík. Marita’s husband has been accused of rape by their babysitter – a case which Úrsúla swears to look into as her first order of business in her new position. The book’s fifth and final main character is the mysterious Stella, who works as a cleaner within the ministry and adds a new dimension to Lilja’s writing.

Stella hails from South America, but her mother ran away to Iceland when she became pregnant with Stella to get away from Stella’s father, who is a “mass murderer” (123). One might wonder whether he is somehow connected to the drug syndicate that Sonja takes her orders from in the trilogy. Stella’s grandmother was apparently a witch in the old country and still visits her granddaughter every year on her birthday. She has taught Stella to perform various feats of magic – in addition to which Stella has a thorough knowledge of Icelandic magical runes. She applies these effectively when needed, like when she uses a rune to turn invisible and move unseen through Reykjavík to spy on her love interest, news anchor Gréta, who Stella has fallen for despite initial reluctance. Stella’s supernatural abilities and her complicated love life remain a side plot but references to the supernatural can be found in all the books Lilja has published since Betrayal.

Primarily, however, Betrayal is a political thriller, which shows how Lilja is yet again forging ahead into uncharted territory. Much like serial killers were fairly uncommon in Icelandic crime thrillers when Magni began tracking one in Steps, political thrillers were a rarity on the Icelandic book market when Betrayal was first published in 2018. Still, the book has much in common with what Lilja refers to as her “mysteries”: the narrative is split into a handful of unconnected storylines that are finally threaded together for a big reveal. (See my more detailed review of Betrayal on the Literature Web)

Cold as Hell

Despite being an independent thriller in its own right, Betrayal also feels like a bit of a palate cleanser within Lilja’s overall output, as her next book, Cold as Hell (Helköld sól, 2019), marks the beginning of a new series. Judging by the first two books, this series is not nearly as interconnected as Snare, Trap and Cage. It is more akin to a traditional crime novel series, where the characters tackle a new case in each book. Here, Lilja continues with the limited timeframe she uses in Betrayal and various characters from her previous books also make an appearance.

In Cold as Hell we meet tough gal Áróra, whose occupation is tracking down fortunes hidden away in offshore accounts and tax havens. Áróra, who is half-Icelandic and lives in the UK, travels to Iceland at the insistence of her mother to search for her sister, who is of course called Ísafold (an old name for Iceland). Ísafold seems to have disappeared – although her brute of husband doesn’t seem all too concerned. While Áróra searches for her sister, the reader learns more about the two sisters, who are very different in personality and appearance. While Ísafold takes after their mother, Áróra has inherited her strength and height from their father, a powerlifter, and usually acts as her sister’s protector. However, she seems to have become fed up with that role after repeatedly failing to convince her sister to leave her violent husband for once and for all.

To help with the search, Áróra contacts an old family friend: Daníel, a hunky detective inspector and older bachelor. Despite their age difference, there is an immediate attraction between the two: a classic will-they-won’t-they tension. Readers get to follow Daníel’s storyline in separate scenes, and thus meet Lady Gúgúlú, the joie-de-vivre drag queen who rents his garage, and the elf rock in his backyard which continually thwarts Daníel’s attempts at lawn maintenance.

Still, Áróra won’t let the search for her sister or her interest in Daníel keep her from seeking out new cases in Iceland. She thinks herself in luck when she meets hotel owner Hákon, who is supposedly bankrupt after serving a sentence for market manipulation but seems to have landed on his feet – as white-collar criminals are prone to do. Áróra decides to uncover his ill-begotten gains in the hope of receiving a hefty finder’s fee from the Icelandic government. That way, she can enjoy her favourite pastime:

...whenever she uncovered hidden funds and returned the money to its rightful owners ... she celebrated by withdrawing her own cut, her finder’s fee, in cash and taking it home with her, where she’d lay the money on her bed and roll around in it. It was an eccentricity of hers which she shared with no one. Her little secret. There was nothing quite like literally rolling around in cash. (51)

Áróra is willing to go quite far to maintain this habit and doesn’t hesitate to seduce and sleep with Hákon, as she imagines that once she has uncovered his hidden funds, she can “take out her fee in Icelandic krona. She’d never tried rolling around in krona before” (51). It is while she is undercover as Hákon’s mistress that Áróra first comes in contact with Agla, who still seems to have some connections within the world of white-collar crime“”.

However, the book’s main plot revolves around Áróra’s search for Ísafold and her guilt over having failed her sister. It turns out that in addition to the violence inflicted within the apartment that Ísafold shared with her husband, various strange doings are taking place within the apartment building that was her final home. The book contains two separate storylines observing Ísafold’s neighbours: The widowed Olga, who has taken in a Syrian refugee named Ómar, and intends to keep him safe from immigration officials seeking to deport him; and Grímur, an oddball loner who suffers from mental problems which manifest themselves in an obsessive hygiene routine that involves shaving all his body hair. There is evidently something more going on with Grímur, but he is skilled in the art of evading suspicion by disguising himself as a harmless weirdo.

Red as Blood

As the similarities in the two titles indicate, Red as Blood (Blóðrauður sjór, 2020) is the second book in the series that begins with Cold as Hell and is also Lilja’s latest book as of this writing. Here we are reacquainted with financial bloodhound Áróra, who is still stuck in Iceland as she can’t find herself to leave the country without knowing her sister’s fate. Even so, there might be other reasons for her extended stay. Detective inspector Daníel is still around and the attraction between the two is no less than before. Through her connections in the world of high-stakes finance, Áróra is called on the scene of a rather unusual criminal case. It appears that the wife of an Icelandic entrepreneur has been kidnapped, with her husband, Flosi, receiving a ransom demand in the amount of two million Euros. The kidnappers order Flosi not to alert the police, but out of sheer desperation he consults with his financial advisor who sends Áróra on the scene. She immediately realises that she is ill-equipped to handle the situation by herself and convinces Flosi to let her contact Daníel, who, along with his colleagues, begins a top-secret investigation into the disappearance of Flosi’s wife Guðrún.

Red as Blood is an unusual crime novel in that it is lacking in the fundamental element found in nearly all Icelandic crime thrillers: There is no body. From this we can tell that Lilja is again doing something different with the Icelandic thriller, which has rarely featured kidnappings as a main plot device before. She readily admits to having taken inspiration from the mysterious disappearance of the wife of Norwegian millionaire Tom Hagen, Anne-Elisabeth Hagen, who was supposedly kidnapped and held ransom for a large sum of electronic currency – a case that is still ongoing. As kidnappings and ransom demands are a rarity in the Nordic countries, the Hagen case is unusual and in fact seems almost surreal. Similarly, Daníel and his fellow officers are in uncharted waters in their investigation, much to the delight of his assistant, the ambitious Helena:

Helena was so fired up when she exited the home that she felt like she was walking on air. She had never heard of a kidnapping in Iceland before. [...] ... carefully planned kidnappings which included a demand for ransom were so rare that she might never get the chance to work on a case like this again. (50)

As has become custom in Lilja’s later books, the chapters are split between a handful of key characters, with Helena being one of them. Even so, the narrative is much tighter than before. There are only four main characters – Áróra, Daníel, Helena and Flosi – who from the start are all working together towards solving the case. This dense structure fits nicely with the limited timeline that has been a signature of Lilja’s books since Betrayal. However, chapters in Flosi’s perspective become rarer as the book progresses, which adds to the cloud of suspicion surrounding him. Despite this, the reader can rest assured that Flosi is at least not directly responsible for the disappearance of his wife – as Tom Hagen has been accused of – as it is Flosi himself who discovers the scene of the crime and goes into shock. Even so, there is certainly something fishy going on in his private and professional life, as Áróra discovers that his company – which supposedly sells garden furniture – somehow holds millions of Euros in hidden offshore accounts.

It’ll be interesting to see how many books Lilja has planned for Daníel and Áróra. The structure of the two books already in print offers a lot of possibilities. The books are self-standing enough that they can be read and enjoyed on their own, but still contain an overarching narrative that connects the books together and hints at a larger plot. This suggests that Lilja has a plan for the series, one which she intends to develop gradually alongside the adventures that Áróra and Daníel run into in each book.

Over the past decade, Lilja Sigurðardóttir has published eight books – one per year since 2015, when the first book about Sonja and Agla began a new chapter in her writing career. During this time, Lilja has systematically developed her writing style and her story structures, in terms of both plot and character, so that today we have a distinct idea of what you might call a “Lilja-ish” crime thriller. Her strength as an author relies heavily on the interconnectivity of her books; how she has threaded them together and established a narrative world that her readers can visit again and again. In this way, she rewards her most loyal readers, those who start each new book with a thorough knowledge of the characters and the underlying storylines, while also continually adding new characters to her gallery. She has also taken the Icelandic crime novel into new territories and adapted it to genres which Icelandic crime writers have not experimented with before. In this way she has laid down a path for other Icelandic crime authors wanting to try out new genres and foreign elements. It is evident that from the start she has been concerned with widening the scope of the Icelandic crime thriller in order to reach people of different ethnicities and social groups. It should be applauded that her books account for the multicultural landscape of modern Icelandic society.

Björn Halldórsson, November 2020

The writing of this overview was made possible by a grant from

The Icelandic Literature Center

Awards

2023 - Storytel Awards: Hundrað óhöpp Hemingways (One hundred Mishaps of Hemingway)

2019 - The Drop of Blood: Svik

2018 - The Drop of Blood: Búrið

2014 - Gríman, Iceland Performing Art Awards: Stóru börnin (play of the year)

Tilnefningar

2023 - The Drop of Blood: Drepsvart hraun (Dark as Night)

2022 - The Drop of Blood: Náhvít jörð (White as Snow)

2018 - The Golden Dagger: Gildran

2017 - The Drop of Blood: Netið

2017 - The Drop of Blood: Gildran

2011 - The Drop of Blood: Fyrirgefningin

2010 - The Drop of Blood: Spor

Dauðadjúp sprunga (Deep as Death)

Read moreÁróru líður betur eftir að lík systur hennar fannst í hraungjótu á Reykjanesi – hún getur loks hætt að leita. En málið er enn óleyst, því að kærastinn sem var talinn hafa drepið Ísafold fannst á sama stað, einnig myrtur. Og þegar Áróra fær vitneskju um óhugnanlegt atriði í tengslum við líkfundinn munar litlu að hún missi tökin á tilverunni. Til að dreifa huganum einbeitir hún sér að peningaþvættismáli sem Daníel vinur hennar er með til rannsóknar. Þar leynist þó fleira undir yfirborðinu og enn á ný liggja þræðirnir í Engihjallann, þar sem Ísafold lifði og dó …. .

Drepsvart hraun (Dark as Night)

Read moreÞegar Áróra fær þær fréttir að ókunnugt barn segist vera systir hennar endurfædd bregður henni illa þótt staðhæfingin sé fráleit.

Betrayal

Read more

Siec

Read more

La cage

Read more

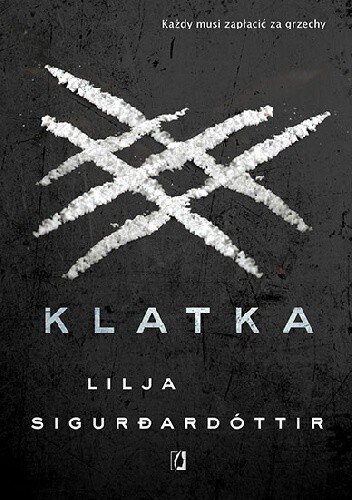

Klatka

Read more