Bio

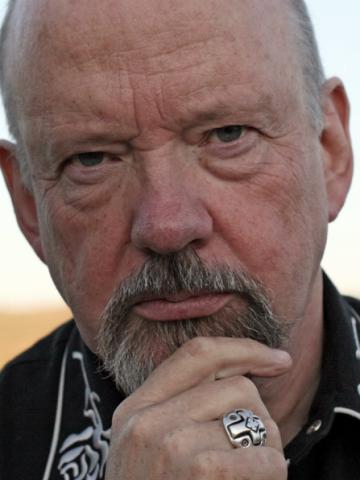

Ólafur Gunnarsson was born in Reykjavík on July 18, 1948. He completed a commercial diploma from The Commercial College of Iceland in 1968. Ólafur worked for merchant Ásbjörn Ólafsson hf. from 1965-1971 and was the driver of the Reykjavík medical emergency from 1972-1978. Ólafur has worked as a writer since 1974.

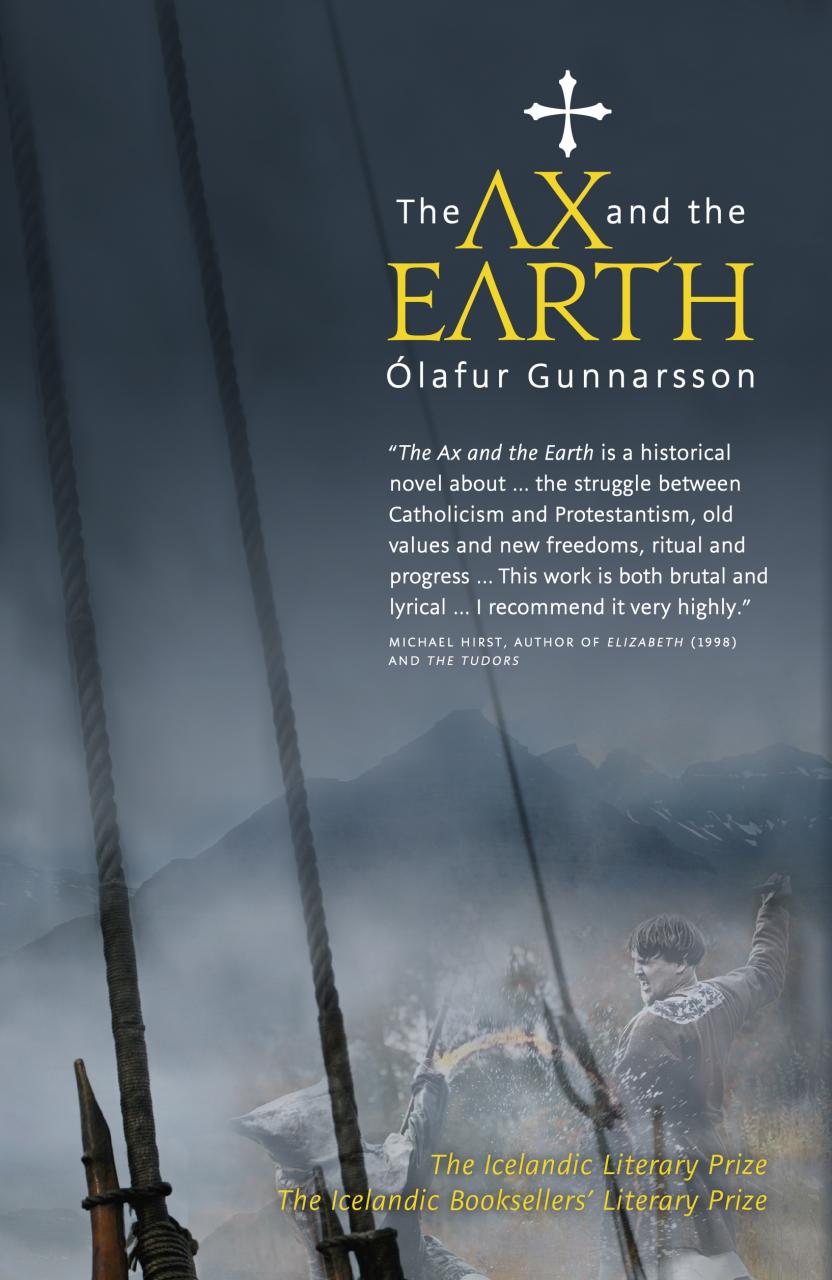

Poetry by Ólafur Gunnarsson had appeared in newspapers and magazines before his first novel, Milljón-prósent menn (Million-Percent Men), was published in 1978. He has published novels, short stories and children’s books as well as a travel story about his road trip with author (and co-author of the book) Einar Kárason in the U.S.A. in 2006. His novel, Tröllakirkja (Troll’s Cathedral, 1996) was nominated for the Icelandic Literature Award in 1992 and the English translation was furthermore nominated for the IMPAC Dublin Literature Award in 1997. An adaptation for the stage premiered at The National Theatre in 1996. He received the Icelandic Literature Prize for his novel, Öxin og jörðin (The Ax and the Earth), in 2004. The film rights for both Öxin og jörðin and the novel Vetrarferðin (Winter Journey, 1999) have been sold.

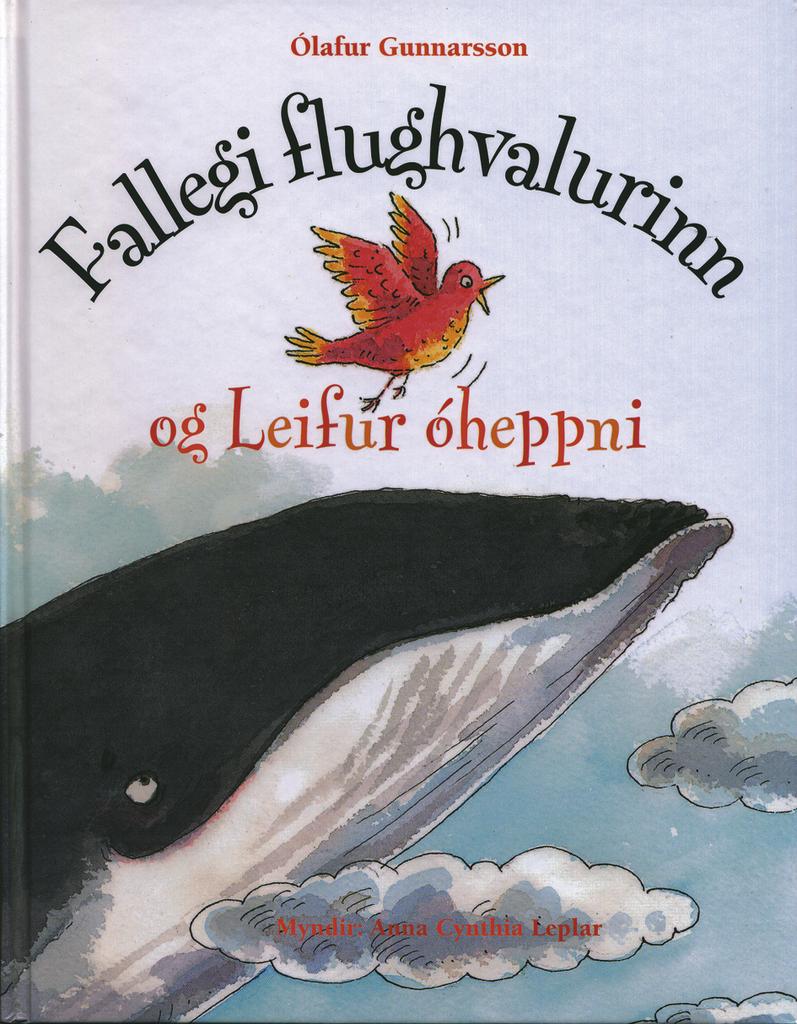

Some of Ólafur’s work has been translated into other languages, the children’s book Fallegi flughvalurinn (The Beautiful Flying Whale, 1999) has been published in Britain, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and The Faeroe Islands, and was nominated to the Nordic Children’s Literature Award in 1990. Some of his novels for adults have been translated to English, German and French. Ólafur has in addition to this, translated novels and plays into Icelandic.

Ólafur is married to Elsa Benjamínsdóttir. They have four sons and live in the Reykjavík suburb Mosfellsbær.

Publisher: JPV.

Author photo: Jóhann Páll Valdimarsson.

From the Author

How I Became a Writer

Ólafur Gunnarsson first became aware of the wonders of literature at the age of ten after reading a story by the incomparable Icelandic short story writer Ásta Sigurðardóttir (1930-1971).

Ólafur, who was born in 1948 then began to write poetry at the age of 19 and published his first book in 1970.

After an infatuation with Ernest Hemingway and some false starts at various jobs, he finally, like many a literary hopeful before him, gained courage to become a full time writer after encountering the works of the great American novelist, Thomas Wolfe, author of Look Homeward Angel (1900-1938). Shortly thereafter he read Moby Dick by Herman Melville which had a tremendous effect on the young apprentice, leading him eventually to the Russians, mainly Dostoevsky, and what became a twenty five year tortuous love affair.

Ólafur emerged from all of the above mentioned via the Icelandic Sagas finally to find his own voice and has today published some twenty works, including ten novels.

About the Author

Ólafur Gunnarsson – Their Best Guardian

For an atheist from the countryside, the novels of Ólafur Gunnarsson constitute unknown territory in more than one sense. In preparing this article I read up on what other literary enthusiasts and critics had written about his work and was surprised to find that none of them does more than give passing notice to the themes I found prevalent in Ólafur’s novels, both old and new, namely religion, history and the city of Reykjavík. Various other themes are mentioned, such as Ólafur’s dealing with traditional ideas about masculinity, his tendency to test the boundaries of conventional realism by inserting exaggerated characters into normal settings, his successful technique of hinting at main themes and major events early in a novel and his ability to create characters that are simultaneously comical and pathetic – downright Quixotic. These comments are apt descriptions of individual texts: I agree with most of these observations and will come back to them. But as I read my way through Ólafur’s novels my attention was repeatedly drawn to the dialogue various characters were involved in with god,1 history and the city. Most main characters are trying to find their place within religion while being firmly placed in Reykjavík. The history of settlement and development of the city is an important and haunting part of their existence. Reykjavík, religion and history will therefore form the main focus areas of this article, much as the themes prevail in Ólafur’s novels.

Religion

The quite yet ever-present deliberation on the role of religion so important in Ólafur’s books is a rather unusual theme in contemporary literature. Sermonising to the reader is not “in” and I’m tempted to maintain that faith – earnest, devout belief – isn’t either. Contemporary discussion about religion takes place in the media, where stories feature terrorism in the name of faith or reactionary, fundamentalist politicians who want to ban contraception and abortions. What you don’t read about in today’s media is individual faith; the private connection between man and god that is based on humility and devotion. This is, however, what Ólafur focuses on in his stories and he manages to broach the subject so softly and tenderly, intertwining subject and characters so completely, that at least this reader did not experience it as sermonising; rather, as an integral part of the story.

Ólafur often juxtaposes materialism, with its idealisation of the individual, with faith in god and Jesus’ message of forgiveness and love for our fellow humans. The best examples can be found in Ólafur’s famous trilogy, comprised of Tröllakirkja (1992; Troll’s Cathedral), Blóðakur (1996; Potter’s Field) and Vetrarferðin (1999; Winter Journey). Literary critic Einar Már Jónsson, in a review of Vetrarferðin in literary journal TMM, likened the trilogy to a triptych, a three-piece, hinged altarpiece. Each book is set in a different time and each is about different characters. Thus each book is an individual piece, just as the centre and sidepieces of a triptych are independent images. But just as the images are hinged together and form a unified message, so the stories are thematically linked in a way that makes it necessary to, like Einar puts it, “let the eyes wander from one unit to the next” (100). The middle book, Blóðakur, is set in the now while Vetrarferðin tells of events that happened around the end of WWII and Tröllakirkja is a mid 20th century novel. Einar explains that in a triptych, the centrepiece constitutes the main image. It conveys the central idea or message while the sidepieces support it thematically and add to its meaning. If we follow Einar’s advice and allow our eyes to wander left and right from the middle novel, a central idea emerges: the battle of Christianity and materialism, both within individuals and in society in general. In Blóðakur, the contemporary novel, struggle for power, individualism and materialism has reached its zenith while the other two books are characterised by internal conflict in the main characters who are finding it difficult to mediate between tragic experiences, selfish longings and traditional Christian values. The doubt and inner turmoil prevalent in both Vetrarferðin and Tröllakirkja do not appear in Blóðakur. Yet the doubts expressed by the characters in the two “sidepiece” novels create a memorable frame that adds to the centre – from right and left, beginning and end, the reader is reminded that there are other options than those that characterise the society that Blóðakur mirrors.

What is more, the choice clearly lies with the individual. The main characters in Vetrarferðin and Tröllakirkja, Sigrún and Sigurbjörn, are similar in that they both choose to prioritise their own worldly advancement over family and traditional moral norms. Both are raised Christians, but while Sigurbjörn is a firm atheist, god forms an important part of Sigrún’s life. Her faith is, however, not characterised by deference to god, but rather some sort of constant defiance. Her story is a tale of loss and sorrow that recalls Job and, in fact, the text frequently refers to the bet that was at the root of Job’s suffering. Even when the Book of Job is not mentioned directly, Sigrún’s conversations with god often recall this bet: she defies her god by repeatedly insisting that unless he fulfils this or that wish, she will stop believing. But even though she looses both her sons, her first husband and foster daughter, she never denies her god. After the death of her younger son and husband, she reveals a deeper faith than that implied by her bets in conversation with her vicar Ágúst: “Do you mean that God apportions fate? … No, that can’t be, she said … I can’t believe that he controls the world like some sort of circus director” (201). It is therefore the god-given free will and personal action that decide an individual’s fate. Sigrún is quite aware of this and bitterly adds that “some things we bring about ourselves” (201). Towards the end of the story, Sigrún suffers a kind off nervous breakdown upon the death of her foster daughter, the person she cared for most. Despite loss and suffering, she remembers that god is with her always, even unto the end of the world. And so, she is never alone, and walks away from death and sorrow “surprisingly surefooted, as if someone was keeping watch over her” (482).

Architect Sigurbjörn, the main character in Tröllakirkja, is brought up in the shadow of a religious older brother who travels overseas to study theology, contracts a disease and dies abroad, a firm believer to the end. Sigurbjörn on the other hand, heir apparent to his brother’s theology studies, upon his death looses faith in a cold-hearted god that allowed such a sincere and kind man like his adored brother to die – a man who, in addition to his other good qualities, was a true believer. Grief and anger make Sigurbjörn unable to forgive god and the internal struggle, ending in a denial of god, leaves deep wounds in his soul. Sigurbjörn is confirmed in his rejection of god when his young son is raped and the rapist pardoned by the president after a very short stint in prison. His family disintegrates subsequent to the incident, largely due to his tendency to see guilt everywhere and in everyone; guilt that he cannot forgive. Where is the justice in all this? How can a loving god allow the innocent to suffer so? The inner struggle between Sigurbjörn’s Christian upbringing, his brother’s memory and thirst for revenge is extremely poignant:

‘What would you have done in my place, brother Jóhannes?’ Sigurbjörn asked out loud, alone in the parlour. ‘Prayed for your enemy? I find the very idea repulsive. The God of the Old Testament is more to my liking.’

He stumbled around the house, exhausted and restless. ‘There is something servile about Christ’s teaching,’ he muttered, snatches of biblical quotations coming into his mind: ‘Vengeance is mine – an eye for an eye – he that rejects me rejects Him who sent me.’ What if Christ really is the son of God? And what if there is an eternal life? That would be horrible. And what if he says at the end of the world, ‘I never knew you.’ Because I have to go and kill this damned man, take my shotgun and shoot him in the face. I can wait until he gets out. I can wait. But will I then have to gnash my teeth in darkness until the end of the world if I kill him? Is revenge worth that much? But I can’t live like this. And I can’t kiss the hands that shamed my Tóti.

(Troll’s Cathedral, Mare’s Nest 1996, p. 201-202)

Sigurbjörn finally looses his grip on sanity, kills his only friend instead of the rapist and ends up in jail. His incapability to forgive – god, his fellow human beings and himself – becomes a crushing weight that finally breaks him. Throughout it is perfectly clear that he chooses not to forgive – his personality is always hard with a tendency to self-pity, although circumstances and his own decisions confirm these character traits. I agree with what Páll Valsson has to say about the morale of Tröllakirkja in this respect: “story events and the fate of the characters are mostly due to personality traits and temperament, although coincidence is also at the root of occurrences … The text constitutes a clear rejection of the view that society conditions the individual and can therefore be held responsible for personal mishaps” (102).

We are given free will in order to love and forgive, but we are also given desires that can lead to the kind of unhappiness, corruption and anger that characterises the community which Blóðakur mirrors. The self-centeredness and egotism of main characters Hörður and Dagný is apparent in their prioritising of worldly goods and comfort over all else. Dagný remains loyal to her husband only as long as he has money and Hörður takes advantage of political corruption to humiliate his sister-in-law in the eyes of the nation in order to acquire his wife’s inheritance, even though he neither loves nor respects his wife. Materialism is their only belief and they care for nothing and respect nothing beyond their own person. Selfish act follows selfish decision and they cause both themselves and their families a great deal of unhappiness. But the choices are theirs to make.

Reykjavík

It is neither unusual nor unexpected that realist novels like the Tröllakirkja trilogy should employ a real-life setting – this the reader accepts as a matter of course. On occasion, however, Ólafur has turned sharply away from his usual realism and tried modern fantasy for a fit. The novels Gaga (1984 and 2000; Gaga), Heilagur andi og englar vítis (1986; Holy Spirit and the Angels from Hell) and short story “Grátt silfur”, published in Sögur úr skuggahverfinu (1990; Tales from the Shadows), all draw on the traditions of science fiction. Gaga is the story of a man who wakes up one morning convinced that he is on Mars, the red planet. The fact that his room and general environment is a perfect replica of that on Earth only testifies to a well-known old Martian trick: he knew “that this was what they did on Mars if they didn’t like a visitor.” (Gaga, Penumbra Press 1988, p. 7). It is hard to summarise the complicated plot of Heilagur andi but the gist of it is that main character Össur-mamma tries to save the world from the nuclear bomb and in so doing comes into conflict with motorcycle gang Hell’s Angels, based at/in Mount Hekla. The story of a historian who travels backwards in time in his brother’s time travelling device, “Grátt silfur”, is an Icelandic version of H.G. Wells’ Time Machine. What is unusual about these science fiction stories is that they are all set in a rather mundane environment – they all more or less take place in contemporary Reykjavík.

But the familiarity of the setting is important, because the author is discussing highly serious matters in an indirect fashion. Interviewed by Einar Kárason and Guðmundur Andri Thorsson, and speaking of Gaga and Heilagur andi, Ólafur long ago declared that

I’m of the opinion that contemporary authors must champion a positive attitude towards life, show respect for the planet – that’s what I think authors must aim at. This is because we live in such terrible times that the very Earth trembles with fear. The author must be for life even though he sacrifices everything else. (41)

While the stories are fantasies, their morale is realistic and aimed at Earth-bound readers, such as contemporary residents of Reykjavík. These two books, to a greater degree than Ólafur’s other fiction, convey a definite morale and can even be read as modern fables. “To treat one’s fellow badly,” Össur-mamma writes in a letter to the newspapers, “that is the atomic bomb” (19). The message is that it does not take a bomb to destroy society as we know it and the Earth itself – we are all engaged in this destruction in tiny, everyday acts that allow evil to enter the world. In this sense, the Astronaut in Gaga detonates a nuclear bomb when he kills a baby in its cradle. Such an evil and pointless act constitutes a betrayal of human kind and the Earth, as surely as if he had set off a real bomb. To ensure that readers emphasise with the rather unusual tales of Össur-mamma and the Astronaut, these take place in well-know spots that readers instantly recognise, such as park Hljómskálagarðurinn and shopping-street Laugarvegur.

The realistic environment serves to reach the reader and remind him or her that these events not only take place in a familiar environment but actually happen in the homes of many Icelanders. Ljóstollur (1980: Light Duty) is dissimilar to Ólafur’s fantasies yet uses locale and mise-en-scène to a similar end. In short, the story is horrific. It is the negative bildungsroman of a very unexceptional young boy in Reykjavík; negative in the sense that instead of attaining real maturity, the protagonist is corrupted upon entering adult society. Stebbi is such a very ordinary boy and his environment so familiar that the reader cannot but concede that the factors shaping his character actually constitute a part of our reality. His sister is brutally raped in her own home and both the rape and resulting pregnancy are dismissed by the men in her life with the old-fashioned, but sadly familiar, ‘she was asking for it’. Stebbi’s situation does not improve when his father gets him hired at the factory where the old man is foreman. In order to ‘become a man’ and gain admittance to the macho community at the factory, Stebbi must adopt a disdainful attitude towards women, hatred of homosexuals and start teasing and persecute those weaker than himself. Descriptions of bullying at the factory, especially of suspected gays, are horrific. While the first-person narrative affects a certain gap between Stebbi’s description of events and the reader’s understanding of same, it is hard not to sympathise with the boy, even when he gives in to pressure from the other men and denounces his gay friend. Stebbi’s choice is certainly wrong, but his decisions are shaped by the past choices of other inhabitants of the familiar Reykjavík.

History

“The text in this book has no historical value” Ólafur proclaims on the flyleaf of Tröllakirkja and later, on the flyleaf of Vetrarferðin, repeats that the book has no “historical value”. Höfuðlausn (2005; Head Ransom), in the author’s dedication, is defined as a fictitious text. Öxin og jörðin (2003; The Axe and the Earth) is described as “a historic novel about Bishop Jón Arason and his sons”. What is the reader supposed to make of these disclaimers? Read with care? Don’t take this text too seriously? It can be hard for readers to decide what attitude to adopt towards historic fiction and authors must understandably tread with care when putting words in the mouths of historic and well-known figures akin to Bishop Jón Arason, artist Muggur and writer Gunnar Gunnarsson. Öxin og jörðin in is an interpretation of history, not historic fact. But what of historic facts – of history? Where are indisputable facts to be found? The truth? It may be possible to verify certain historic dates and actual moves of people from A to B, yet history is comprised of ndividuals – people with feelings and reasons for travelling from A to B on 7 November 1550. These reasons form the main focus of Ólafur’s fictitious histories, especially the most recent ones, Höfuðlausn and Öxin og jörðin.

Höfuðlausn revolves around events that took place during the summer of 1919 when Danish filmmakers came to Reykjavík to film novel Saga Borgarættarinnar by Gunnar Gunnarsson. This is also the summer when Jakob transforms a centipede into a worm to spare the feelings of an unknown girl that sits in front of him at the movies. Ólafur introduces the main characters in the first few lines of the novel – Jakob and the girl, not the centipede – even though the girl does not appear again until about mid-book. Neither of them, let alone the reader, suspects that these two will eventually marry. Ólafur employs these clues, hinting at what is to come, in some of his other books too and does it very well. A man sitting on a bench on Skólavörðuholtið, who for no apparent reason scares Sigurbjörn on the first pages of Tröllakirkja, turns out to be a deciding influence later in Sigurbjörn’s life. In both Tröllakirkja and Höfuðlausn these omens are introduced as an integral part of the storyline and are not revealed as such until their time has come later in the story. The omens add depth to the stories and evoke trust in the omniscient author who obviously knew all along where the story would lead the reader.

Jakob’s path to Ásthildur, the girl from the movies, is winding and takes him east to Selfoss, Keldur and Þingvellir, where he travels as part of his job as reporter, a ‘prop’, chauffeur and carpenter during the film-making process. Jakob is partially based on reporter Árni Óla, a historic figure who was engaged to travel with the camera crew and wrote about its progress in Morgunblaðið. But the reason why Jakob takes on sundry jobs related to the film is his infatuation, with movies certainly, but mostly with leading actress Elisabet Jacobsen. She turns out to be quite a bitch that uses Jakob’s crush to make her husband jealous and, to make matters worse, repeatedly pokes fun at Jakob’s love in front of the whole crew. Was the real Elisabet that sort of person? Who knows, but driven to desperation, Jakob gets drunk with artist Muggur and breaks his leg. This coincidence puts him in the position to renew his acquaintance with Ásthildur, apprentice goldsmith, who works at a shop below the doctor’s office where Jakob’s leg is attended to. Together they loose, love, cry and live. It is the warmth evident in the author’s description of their fate, as well as his sincere interest in his characters, that form the most memorable aspect of the book. Historic events and the development of Reykjavík form the backdrop to the story of Ásthildur and Jakob in an interesting manner that adds layers to fictional characters, yet it is their fate, feelings and thoughts that are the real facts of the book.

Similarly, historic events frame Öxin og jörðin, but the story is driven by the passion and personalities of the main characters. The difference is that in Öxin og jörðin, the characters are only half-fictional, as it tells of the conflict that lead to Iceland’s nation-wide conversion from Catholicism and the beheading of the country’s last Catholic Bishop, Jón Arason, along with his sons. In this text, the author is as omniscient as he gets in Ólafur’s work. The author’s voice is so close to that of his characters that he moves, in a single sentence, from a third-person narrative to speaking with the voice of the current character, here King of Denmark, Christian III:

He had sent for Bishop Jón, asked him to come to his side but even though the King had promised full amnesty Jón had not heeded his call and, what is more, gone against our wishes and church orders. He also forces and coerces our subjects; behaviour that we cannot tolerate. (159)

The above is also a good example of how unconditionally the author serves the characters, rather then the reverse. The characters are numerous and they take turns carrying the narrative. Because of this narrative technique it would be easy for the omniscient author to let his opinions of the thoughts and actions of characters shape the chapters in which they speak, but by allowing the voice of individual characters to encroach on the author’s narration like in the quote above, they all get their own say. When Bishop Jón speaks, the actions and personality of ‘his daughter’ Sigurður are obviously despicable, but when Sigurður gets his say, it is the father who fails to understand his son’s actually sincere commitment to Lutheranism over Catholicism.

The characters in Öxin og jörðin emerge vivid and memorable in Ólafur’s treatment of them. Ari Jónsson especially, and his unwavering loyalty to a father whose believes he cannot share, is larger than life. Ari’s quiet, deep grief upon the death of his wife Halldóra largely explains his later indifference about his worldly fate. And this is what makes well-written historic novels so important – they make history come alive for the reader. Ari was a man who loved his wife. Halldóra suffered because Helga, her mother-in-law, disliked her. Christian Schriver was prepared to sacrifice everything for his son Baldvin. Jón Ólafsson, executioner of Bishop Jón, Björn and Ari, was a weak-minded kid who was coerced into the role by the real killers, Jón Bjarnason, Daði, Marteinn and others, all men who lacked the courage and conviction to do the job themselves. These are not names I remember from any history lessons at school, although I, like every schoolchild in Iceland, am certain to have been tested on them and the important year 1550. But I suspect that now that Ólafur has given the names personalities and emotions – however fictitious these may be – I may even remember that the execution took place on 7 November.

I have not addressed every single one of Ólafur’s texts in this article. His first novel Milljón prósent menn (1978; Million-Percent Men) has not been mentioned, nor have I discussed his children’s books, plays, poems or translations. This is because the novels form the bulk of his oeuvre. Since Milljón prósent menn was published, Ólafur has grown considerably as an author and developed his narrative style, choice of subject matter and characterisation. But even in his first book he had started contemplating the effects of materialism on society, with a focus on Reykjavík. This subject has continued close to his heart and become intertwined with a deeper discussion about the role of religion in individuals and the importance of history in his more recent books. This discussion is gentle and free from the kind of sermonising that might be expected in realism and social realism. Ólafur’s historic novels may not have conventional factual value but they contrive to show the reader that history is shaped by people made of flesh and blood. In so doing, Ólafur affects an interest in human action and demonstrates how the choices made by individuals have led to actual events rather than simply describe accepted views of history. For this reason I find Ólafur’s stories to be the best (hi)story of the men and women who shaped it.

© Agnes Vogler, 2006

1. Throughout this article, I will not capitalise god. In my opinion, it is not a proper name, any more than goddess.

Bibliography

Einar Kárason and Guðmundur Andri Thorsson. “Ég bý í húsi undir klöpp: Einar Kárason og Guðmundur Andri Thorsson ræða við Ólaf Gunnarsson”

Teningur 1987: 4, p. 35-43.

Einar Már Jónsson. “Besti drátturinn?”

TMM 2000: 2, p. 98-103.

Páll Valsson. “Hin heilaga fjölskylda”

TMM 1993: 2, p. 101-106.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 435, 440, 459.

On individual works

Tröllakirkja (Troll’s Cathedral)

Ingi Bogi Bogason: “Når drømmen er for stor : de islandske sagaers helteverden i ny afspejling = When a dream is too big : the world of the Icelandic sagas’ heroes from a new angle”

Nordisk litteratur 1993, pp. 15.

Awards

2003 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Öxin og jörðin (The Axe and the Earth)

1999 – The National Broadcasting Service Writer’s Fund

Nominations

1992 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Tröllakirkja (Troll’s Cathedral)

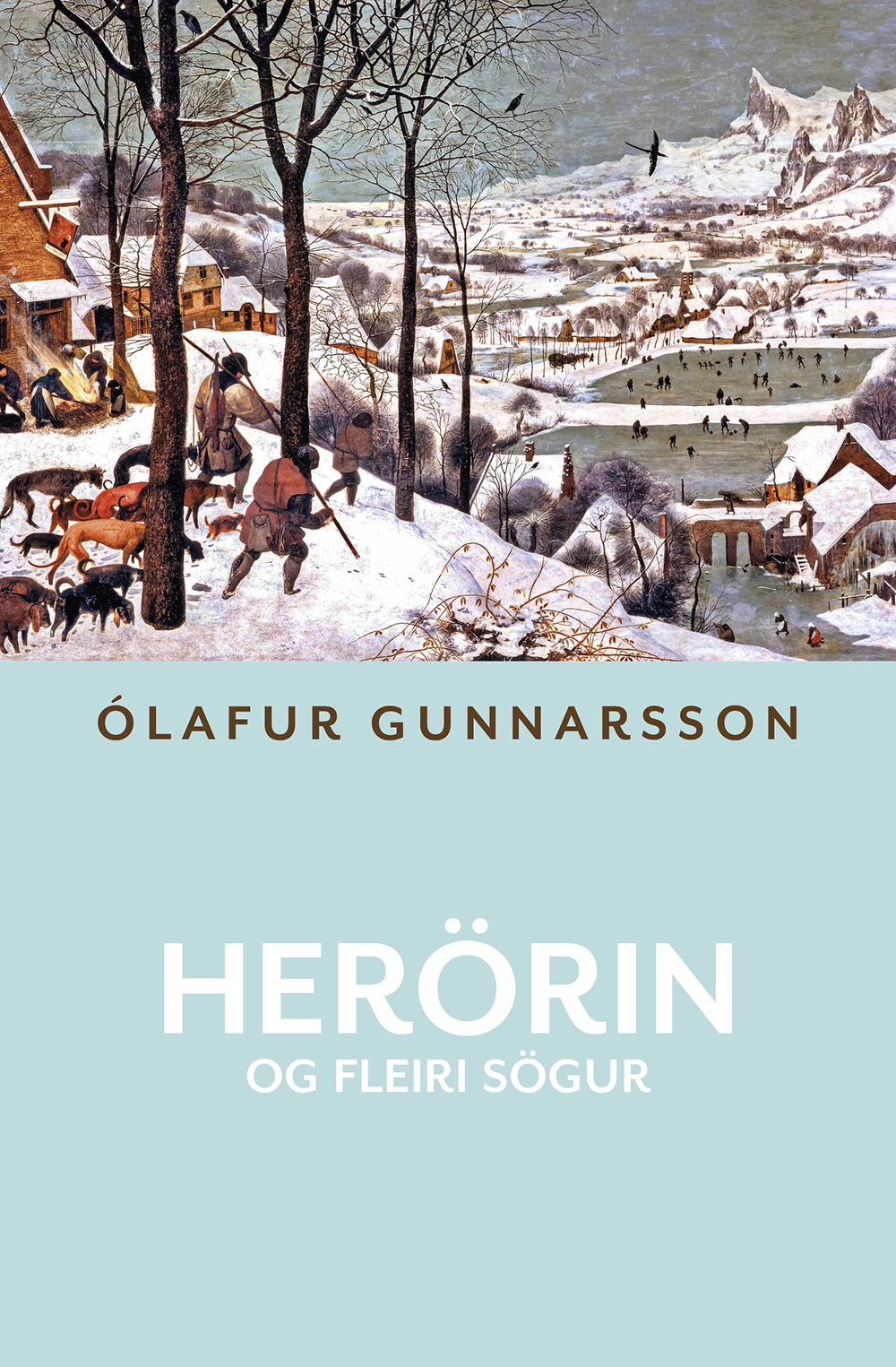

Herörin og fleiri sögur (The Arrow of War and Other Stories)

Read moreDauðvona lögfræðingur snæðir kjötsúpu með fyrrverandi eiginkonu sinni, AA-maður fer til að biðja gamlan bekkjarfélaga fyrirgefningar, húsgagnasmiður býður langveikri dóttur sinni í hvalaskoðun og átök leynifélaganna Rauðu rósarinnar og Svörtu handarinnar ná hámarki í blóðugum bardaga á Skólavörðuholti. Um þetta og margt fleira má lesa í tólf nýjum smásögum eftir Ólaf Gunnarsson. Stíllinn er knappur og oft launfyndinn, sögurnar ýmist bjartar eða dimmar, angurværar eða ærslafullar.

Listamannalaun (Artist's prize)

Read more

Syndarinn (The Sinner)

Read more

The Ax and the Earth

Read more

Málarinn (The Painter)

Read more

Meistaraverkið (The Masterpiece)

Read moreMillion-Percent Men

Read more

Dimmar rósir (Dark Roses)

Read more

Fallegi flughvalurinn og Leifur óheppni (The Beautiful Flying-Whale and Leif the Unlucky)

Read more