Bio

Ólafur Haukur Símonarson was born on August 24, 1947 in Reykjavík. He studied interior design in Copenhagen 1965-1968 and literature in Copenhagen and Strasbourg from 1969-1972. He moved home from Denmark in 1974. Ólafur worked as a producer for two years for The Icelandic National Broadcasting Service, among other things making documentaries about Icelandic daily life. He was the director of Alþýðuleikhúsið (the People’s Theatre) 1980-1982. Ólafur has done numerous jobs, but since 1976 he has mostly dedicated his time to writing and translation.

Ólafur Haukur has been on the board of many societies and associations. He was the chairman of The Icelandic Dramatists’ Union from 1986 – 1999, and was vice-chairman of The Writer’s Union of Iceland. Ólafur has been a member of the board of STEF (the Society of Composers and Holders of Copyright) in Iceland since 1986, he was the vice-president of I.T.I’s (International Theatre Institut) playwrights’ committee 1993-1998, and was a member of the committee for selecting projects for the Theatre Festival in Bonn (Bonner Theater Biennale) in 1992 and 1994.

Ólafur Haukur has written a number of popular plays for the stage, radio and television. Examples are Blómarósir (Lovely Lasses), Bílaverkstæði Badda (Baddi’s Garage), Hafið (The Sea), Gauragangur (Hullabaloo), Þrek og tár (Endurance and Tears) and Kennarar óskast (Teaching Vacancies). He adapted his play Bílaverkstæði Badda for the cinema as Ryð (Rust), and Hafið has also been adapted for the screen (by Baltasar Kormákur).

Besides poetry and short stories Ólafur has published a number of novels, such as Vatn á myllu kölska (Water on the Devils Mill), Gauragangur (Hullabaloo) and Rigning með köflum (Rain With Sunny Spells). In 1997 the crime novel Líkið í rauða bílnum (The Corpse in the Red Car) was awarded a French literature prize as the best Nordic crime story. Ólafur Haukur has translated a number of books, plays and films. He has written non-fiction works and his articles and short stories have appeared in newspapers, magazines and collection in Iceland and abroad. Furthermore he is the author of many popular songs and lyrics.

Ólafur Haukur is married with three children. He lives in Reykjavík.

About the Author

Ólafur Haukur Símonarson: Uprooting Rosy Social Myths

Since the publication of his first volume of poems, Unglingarnir í eldofninum (The Teenagers in the Brick Oven) in 1970, Ólafur Haukur Símonarson has produced a substantive oeuvre of poetry, novels, translations, films and plays. His plays, regularly staged by both professional and amateur theatre companies, have been, and continue to be, extremely popular with audiences. This general popularity was also apparent when his play Hafið (The Sea, 1992) was filmed in 2002. In Iceland, all 16-year-old students undergo a standard examination at the end of mandatory public education, and I myself was part of a generation that studied Ólafur’s novel Gauragangur (Hullabaloo, 1988) for the Icelandic language and literature test. For a writer to have their text chosen to represent contemporary literature alongside the Icelandic sagas is quite an honour – in some ways even more of a recognition than literary awards can be; certainly few awards can similarly secure a readership. In general, texts that make it into a curriculum have been accorded a certain status within a culture, both as an important part of a society’s literary heritage and as an important medium of its culture. And it is appropriate that a large proportion of the nation be familiar with Ólafur’s work, as his texts contain an extensive discussion of the national character, Icelandic culture, the individuals it creates and that shape it in turn. This discussion is frequently critical, deconstructing national myths such as the pervasive story that there is no class division in Iceland, and that the community’s booming economy is based on a general equality. The novels Vatn á millu kölska (Water on the Devil’s Mill, 1978) and Galeiðan (The Galley, 1980) serve as examples of the social critique prevalent in Ólafur’s work, and together demonstrate many of the traits typical in his texts, both novels, poems and plays. I will therefore begin this discussion of Ólafur’s oeuvre with an examination of the two novels, focusing on the issues they raise and the aesthetic as well as rhetorical devises that frame the social critique.

I

The division between labourers and the ruling class in The Galley and Water on the Devil’s Mill respectively seems at first glance to be complete. Two distinct social spheres, two separate books, two different narrative approaches. The Galley is a mosaic of episodes, each telling the different stories of people connected in one way or another to ‘Umbúðasmiðjan’, a factory of some sort. Yet the women working ‘the line’, the conveyor belt in the factory, provide the main focus of the story. They are a disparate group, but alike in that they are firmly tied to the metaphorical oars: uneducated like Rósa, single mothers like Jónína and Marta, or with a history of mental illness like Brynja. While the punches of the time clock have replaced the rhythmic beating of the slavers’ drum, the book’s title in fact provides an exhaustive description of their situation. The overseer, Lárus, is adamant that once the women have punched themselves in, they are “expected to start working” (31). If they stop, even “for five minutes to knuckle their backs, Lárus shows up in a heartbeat” (40). The working and social environment described in the novel is characterised by chasms and divisions. The foreman sits in an elevated glass office from where he can observe the women working ‘the line’ while they cannot return his gaze without risking the loss of a finger in the non-regulation equipment. In the cafeteria, the “office personnel sit at a special table” and “women do not sit at the men’s table”, while the boss comes around about as often as paid holidays (58, 59).

The women’s existence revolves around their work and the narrative is ingeniously adapted to reflect this fact. None of the women functions as a main character nor do any of them speak in the first person. This style promotes the perception of the women as a group, or faceless mob – workers, rather than individuals. Furthermore, the stagnation and torpor characterising their working lives seems to have influenced their perception of self to such a degree that they have come to think of themselves as little more than labourers. While narrative techniques are similarly used to support the subject matter in Water on the Devil’s Mill, this novel tells the story of an individual. As the descendant of a long line of CEOs and directors, Gunnar Hansson, programmer at The Network, has never wanted for any worldly good. In contrast to the fluctuating point of view in The Galley, Gunnar Hansson is the unwavering centre of attention in the story of his life. Despite this foregrounding of self, Gunnar owes his social position to family, friends and political connections rather than talent, and this is a fact he himself is painfully aware of. Contempt is the hallmark of his character, mainly self-contempt, but also contempt for his family and class and the lives they lead. In addition, Gunnar is afraid to face up to the decisions he has to make, but is at the same time apprehensive about the course his life has taken, or been made to take, because of decisions made by others, most notably his father. Gunnar has always done what his family and class demanded. At University, he undertook a prudent course of study rather than the arts major he would have chosen for himself, he married his (very) casual girlfriend when she accidentally fell pregnant, and after graduation he embarked on the carrier his father had mapped out for him. Even so, Gunnar has some ambition for his job as a programmer, and, encouraged by his radical young assistant Kristín, he proposes a programme about the social and economic conditions of Icelandic factory workers. The head of department is less than excited by Gunnar’s proposal. Politically allied with the board of directors and the government party, the head is more interested in portraying life in the country positively rather than realistically.

The worlds described in Water on the Devil’s Mill and The Galley are only brought into contact once, when Kristín starts interviewing female labourers for the vetoed programme. One interviewee turns out to be Jónína, a single mother working long hours for low wages at ‘the line’ in the Factory. Gunnar Hansson later listens to a recording of the interview, and this exaggerates the rift between the different social positions Gunnar and Jónína represent. Jónína remains an object, her life raw material out of which Gunnar may possibly shape something of interest, the profits from which would of course benefit others than Jónína herself. But her story will never be told, because both Gunnar and his head of department know that the mundane story of Jónína’s life could never be made lucrative: there are no interested buyers and therefore her story is meaningless. The different narrative techniques and treatment of subject matter evident in the two texts serve to illustrate how wide the gap between proletarians and upper classes, women and men is, even in supposedly egalitarian Iceland. But does the author simultaneously suggest that this gap cannot be bridged? Is egalitarianism nothing more than an unattainable ideal? Do most modern individuals exist in isolation from each other, reduced to inhumane labouring automatons?

I started this comparison of The Galley and Water on the Devil’s Mill with the words ‘at first glance’, and while I do not wish to suggest that the discussion of class division in Iceland is in any way superficial – to the contrary – I think there is more to the two texts than a cursory examination would suggest. On the surface, Gunnar Hansson, programmer and rich kid, and Jónína Ingimarsdóttir, single mother and blue-collar labourer, do not seem to have anything in common, but in fact they are both wrestling with the same problem: freedom. Or, more accurately, a lack thereof. The Galley and Water on the Devil’s Mill describe different people leading different lives, but they all have one thing in common: they belong to the same community. Their lives are shaped and bound by the same society, whatever their standing in the social hierarchy. In his 1977 thesis on the short story collection “‘Dæmalaus ævintýri’ eftir Ólaf Hauk Símonarson” (“‘Unprecedented Fables’ by Ólafur Haukur Símonarson”), Matthías Viðar Sæmundsson contends that the schism characterising modern existence provides its main focus. This schism, as argued by Ólafur, polarises the working life and the soul of the individual, separating emotion and reason. Matthías suggests that one of the purposes of the stories is to provide a critical discussion of contemporary bourgeois community, but first and foremost to critique capitalism’s commodification of culture and preference of logic at the expense of emotions. The alienation caused by the eradication of art and emotion from everyday life is a social problem, but it is at the root of the frustration and sense of enchainment experienced by individuals such as Gunnar and Jónína. The natural creativity and inventiveness of both characters has been stunted, forced to take second place to society’s demand to produce profit. Working ‘the line’, Jónína feels like her body and mind “have been forced into a mechanised semblance of awareness” (41) while Gunnar is never allowed to produce material critical of the cultural and political regime. Both Gunnar and Jónína have become automatons, flesh and blood slaves to the supply-and-demand policy of a capitalist society that cannot accommodate ideals or emotions.

II

Another essayist, Björg Kofoed-Hansen, writing about the novel Vík milli vina (Far Between Friends, 1983) in 1986, largely agrees with Matthías’ analysis, adding that this book furthermore serves the purpose of raising awareness about what the author considers two of modernity’s most immediate problems: lack of ideals and apathy. The torpor engendered by society’s indifference to art and emotion in a mechanised everyday life, causes individuals to lose a sense of responsibility, both for their own and their neighbours’ actions. Alienation from such responsibility is not only possible but perfectly reasonable when people feel, like Einar does in Þrek og Tár (Endurance and Tears, 1995), that “I don’t feel like I arrive at a decision, it’s more like decisions arrive at me” (66). Einar isn’t the only person to feel this way: “Maybe, Gunnar Hansson thinks, you never take a decision. The decision takes you” (Water on the Devil’s Mill, 39). These sentiments are also echoed by the narrator in the lyric novel Almanak Jóðvinafélagsins (The Society for Child Promotion’s Almanac, 1981), who speculates that “you never really find a conclusion … it’s the conclusion that finds you” (12). When characters have become reconciled to letting decisions take them rather than analysing situations before arriving at an independent conclusion, art and ideals have been defeated by the social mechanising of the individual.

This condition is one of the main themes in Far Between Friends, the story of a group of Icelanders that studied together in Copenhagen around 1968. The comparison between the emotional energy and vision characterising that period, especially amongst young people, provides a stark contrast to the lack of drive and ideals in the same individuals ten or fifteen years later, when the structures of society have slowly but inexorably chained them to the galley. One of the main characters in Far Between Friends, Ingunn, describes the process in these words:

We believed that soon we would party with the whole of struggling humanity. When that didn’t happen we shut our doors and tried to forget what was outside … It is possible to forget what’s outside, but only be numbing the senses. (187)

While Ingunn accepts a measure of responsibility for her currant situation, the narrator, Pétur, vents his frustration on everyone and everything around him because he cannot admit that most of his anger is directed at himself. Pétur has realised none of his dreams, given up on his ideals, and hates his old friend Kári for raising the issues he cannot resolve: “What do you care about? What do you believe in? What have you accomplished?” (17). The simple answer is nothing. Much like everyone else, Pétur has compromised his ideals to meet social demands. He has become chained to the oars, rowing the galley according to direction rather than plotting an independent coarse.

More demanding than either The Galley or Water on the Devil’s Mill, the narrative style of Far Between Friends is often reminiscent of the fact that Ólafur is also a prolific play write. Long dialogues between protagonists tend to become monologues in which one character waxes lyrical on one of the author’s favourite subjects and seems to be addressing the reader/audience rather than his or her ostensible interlocutor. Dashes rather than inverted commas preface direct speech, and since the novel is based on dialogue, the prominent dashes recall a script rather than a traditional novel. Just like in The Galley, Far Between Friends employs a wandering centre of consciousness, but this technique is interrupted by the story of Pétur, told in the first person. Pétur purports to be the narrator, recording his friends’ lives and thoughts. In a story rife with love triangles, argument and violence – to which he is most often a party, if not the instigator – Pétur can hardly be called an objective observer. Hints as to the unreliable nature of Pétur’s writings are interspersed throughout the story, often appearing in parentheses, as interjections from Pétur: “(I definitely did not say all that, but I wish I had)” and “(perhaps she never said that; perhaps I slept, and dreamt it”) (113, 123).

This keeps readers on their toes, always questioning whether or not Pétur can be telling the truth about conversations and events in others’ lives. I do not think however, that his reliability (or lack thereof) as narrator becomes much of an issue. This is because the characters in Far Between Friends do not constitute the most important part of the novel; rather, they are tools through which the author voices a certain political and social critique. Most of the characters are types, comprised of traits and stock attributes, or even merely an embodied idea, standing in for the views of one particular social group. Both Pétur and Halldór stand for the bitter and misunderstood artist, Kári gives voice to the bourgeois mindset, Aðalbjörg the self-effacing lover, Guðrún embodies the perfect yet undervalued housewife, Guðni the corrupt businessman, Marteinn the uncool provincial, Hjördís the oppressed woman, Guðmundur moral corruption and Hafliði’s lack of personality makes him the perfect tabula rasa upon which society can write its demands. This narrative style confirms the opinion voiced in both The Galley and Water on the Devil’s Mill – that the social predominates in the formation of the individual. Society’s greatest problems, as perceived by the author, are therefore given human form so that they can be dealt with in a more concrete fashion. This technique is reminiscent of so-called ‘problem plays’, in which human interaction and dialogue is mainly used to illustrate social evils.

III

In a problem play, characterisation serves the critique, and I find this to be an apt description of not only the novel Far Between Friends, but a number of plays by Ólafur Haukur as well. In his aforementioned essay, Matthías Viðar says of the characters in Unprecedented Fables that they are “one-dimensional. The author prefers to focus on the social in human existence” (62). This comment explains why some of the characters seem to haunt a number of different plays. Sigurður, the monarch of the house in Milli skinns og hörunds (Under the Skin, 1984), reappears as Þórður in The Sea, while the angry and emotionally handicapped Einar in Endurance and Tears appears to be a reincarnation of Alli in Kjöt (Meat, 1990) and Haddi’s inability to take responsibility for his own choices in Under the Skin is undeniably reminiscent of Ágúst’s dilemma in The Sea. Female characters can simply be divided into three classic groups: mothers, wives, or whores. “The ‘good’ characters, so to speak, are noticeably fewer that the ‘bad’ ones, although perhaps it would be more fitting to describe them as positive and negative characters” says Atli Rafn Kristinsson of the characters in Water on the Devil’s Mill, and these words also apply to Ólafur’s plays (361). I further agree with Atli’s observation that “Ólafur Haukur tends to create rather one-sided characters” (360), but like Matthías, I think that this is done intentionally. With such protagonists as Ormur Óðinsson in Hullabaloo, Ólafur has certainly demonstrated that he is a competent writer of two-dimensional characters who respond to situations in a unique way, develop and evolve. The characters in the plays mentioned above on the other hand, are types, representing the attitudes of certain social groups rather than the opinions of realistic individuals. This could be accounted a flaw in Ólafur’s writing, except for the fact that it seems to be done on purpose. As an author, his main intention may not be to create realistic characters, but rather to use types to exemplify and criticise aspects of the community.

Although most of Ólafur’s plays and novels take place in Reykjavík, this is by no means a rule, and locale plays an important part in most of his texts. Rigning með köflum (Rain with Sunny Spells, 1996) recounts the experiences of the city boy Jakob, ‘forced’ by his parents to spend a summer on a farm. Meiri gauragangur (More Hullabaloo, 1991) is set in Denmark and The Sea “takes place in a contemporary fishing village” (The Sea, 1992: 2). However, the 2002 film version of The Sea was set in the East Iceland village of Neskaupstaður, and because of its popularity, many will undoubtedly associate the play with that village. It is easy for most readers to recognise the social situation and identify with characters who “walk up Freyjugata road and down Lokastígur lane” (Far Between Friends, 1983: 104). The environment, be it a secluded farm, small seaside village or a slightly bigger seaside village like Reykjavík, is always present in Ólafur’s work and an inextricable part of the characters’ social conditions. Locale and protagonist even merge, as in the instance of narrator Ólafur Haukur Símonarson and Reykjavík in The Society for Child Promotion’s Almanac:

I don’t just admire the views you offer view but also the insights. I know you can be rather rude and display immature sensibilities, but I respect your drive and will to learn. I ignore how susceptible you are to outside influences. And when your skin itches, when you writhe, breath, groan and shout; then you are a part of me. The asphalt, the concrete, the glass, trees, rocks, fire vanes, people and small fishes flapping in the warm fjords – all this belongs to both of us together. – Hello Reykjavík, I say, I’m sure you’d grow up given the time. Maybe the two of us could grow up together. (40)

This organic co-existence of man and environment supports and enhances the social critique, e.g. when the discussion is of exploiting natural resources such as fish, fresh air or water. Familiar characters furthermore serve to bring the issues under discussion home to the reader. Protagonists’ family get-togethers are eerily reminiscent of real ones, describing the forced meetings of men and women who have little but blood in common, don’t really agree on anything, but are obliged by family ties to nod politely and smile. Yet while the problems, violence and injustices of everyday life most often form the main storyline, humour is always part of the mix. Even when the critique is at its sharpest, Ólafur sees to it that the witty repartee between characters forms a sort of relief, making the constant physical and emotional violence and critique more bearable.

IV

Although I do not wish to suggest that the such a multi-faceted oeuvre as that of Ólafur Haukur can be reduced to a single subject, I find that one theme consistently remains foregrounded in the discussion: the importance of art to both society and individuals. Art not only engenders beauty and vision, but also distinguishes between man and machine. Again and again, Ólafur portrays what effects it has on the individual that

it is getting more and more common that art

is short while life is long.(Má ég eiga við þig orð (Could I have a word), 1973:73)

The poem “París ‘68”, which provides a conclusion to this discussion, indicates that the poet has been on a continuous mission to raise awareness about the importance of art and ideals since the beginning of his career. “París ‘68” has featured in two volumes of poetry, published in 1973 and 2003. The inclusion of the poem in the latter publication demonstrates that its message is as relevant today as it was 30 years ago.

When I awoke this morning

I saw that a red rose had grown

from your navel

and was smiling at me

like a child.I hurried into the kitchen

to get water.When I returned it was gone

and you said you never saw

no flower.(Could I have a word, 1973: 56 and

Æskuljóð hvíta mannsins (The Young White Man’s Poetry), 2003: 2)

Agnes Vogler, 2006

References

Atli Rafn Kristinsson. “Ungur maður á túr”.

Tímarit Máls og menningar, volume 3, 1979, p. 357-361.

Björg Kofoed-Hansen. 1986. Vík milli vina eftir Ólaf Hauk Símonarson.

A thesis done at The University of Iceland.

Matthías Viðar Sæmundsson. 1977. Dæmalaus ævintýri eftir Ólaf Hauk Símonarson

A thesis done at The University of Iceland.

Articles

On individual works

Galeiðan (The Galley)

Inge Knutson: “Ólafur Haukur Símonarson. Galeiðan”

Gardar, årsbok 12, 1981, p. 88.

Awards

1997 – Les Boréales de Normandie: Le cadavre dans la voiture rouge (as the best Nordic crime novel of the year)

1993 – DV newspaper’s Cultural Prize, Drama: Hafið (The Sea)

1993 – Icelandic Broadcastin Service Writer’s Fund Award

1990 – The Rouen film festival in France: Ryð (Rust) (Spectator’s Award)

1983 – Reykjavík City Children’s Book Award: Veröld Busters by Bjarne Reuter (for translation)

Nominations

1994 – The Nordic Council’s Drama Award: Hafið (The Sea)

1989 – The Nordic Council’s Literatur Prize: Vatn á myllu kölska (Water on the Devil’s Mill)

Dýragarðurinn: Fólkið í blokkinni (The zoo: the people in the apartment building)

Read more

Aukaverkanir (Side Effects)

Read more

Ugla & Fóa og maðurinn sem fór í hundana (Ugla & Fóa and the Dogged Man)

Read more

Skýjaglópur skrifar bréf (Letters From a Dreamer)

Read more

A Single Wave

Read more

Fuglalíf á Framnesvegi (The Birds of Framnesvegur)

Read more

Fluga á vegg (Fly on the Wall)

Read more

Turmoil

Read moreVaktmester Robbi

Read more

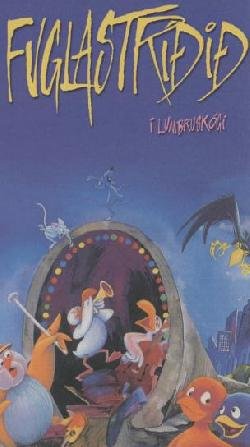

Fuglastríðið í Lumbruskógi (The Birds´ War of Lumbruskógur)

Read more