Bio

Ragnar Jónasson was born in Reykjavík in 1976. He graduated from The Commercial College of Iceland and earned his law degree from The University of Iceland. While studying he worked for the National Broadcasting Service, both on radio and on the television news desk. He has practiced law and teached copyright law at Reykjavík University. He also serves as a board member of the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra, and as the Deputy Chair of the Writers' Union of Iceland.

Ragnar is the co-founder and co-chair of the literary festival Iceland Noir, held annually in Reykjavik.

Ragnar has translated fourteen of Agatha Christie’s crime novels to Icelandic. The first, Sígaunajörðin (Endless Night), was published in 1994. Ragnar also translated the Play Orð gegn orði (Prima Facie) for the National Theatre of Iceland. Ragnar's first crime novel, Fölsk nóta (False Note), was published in 2009, and since then he has written a new Crime novel every year. His books have been translated to multiple languages and have reached bestseller lists and won prizes.

In 2024 the TV series The Darkness (Dimma ), which is based on Ragnar's books about the policewoman Hulda (Dimma, Drungi and Mistur), was premiered. Another TV series from Snjóblinda and more books from that series is in the making and a Movie from the book Úti (Outside) is being developed.

Ragnar’s website is www.ragnarjonasson.com.

From the Author

From Ragnar Jónasson

I’ve been writing almost since I can remember.

You might say I was raised around books and writing. My grandfather and namesake was a prolific writer and used to tell me all the time: “You need to keep writing, junior.” My father, who was an editor and author, and my mother both encouraged me to write stories. And I had other writer’s role models in my family; my uncle on my father’s side for instance was an author and publisher.

I started writing stories and poems just as soon as I could hold a pen, and created my first “novel” at an early age – an illustrated children’s book called “Óli Goes on an Adventure” (“Óli fer í ævintýraferð”). At eleven or twelve I wrote my first crime story, dramatically entitled “In the London Fog” (or “Í Lundúnaþokunni”). As you might imagine, these books are (and will remain) unpublished.

At seventeen I was given the chance to translate a crime novel from English into Icelandic. I kept translating a book a year, first alongside my studies and then in my spare time, until I had translated fourteen of them.

All my novels have been detective stories or crime novels (the distinction may be a bit fuzzy), although my writing interests neither begin nor end there. There’s something about the form, the mystery and the plotting, that I find fascinating. I enjoy writing different people and their reactions to tough situations, and this all fits well within the scope of the crime novel.

If asked why I write I think the answer would be that I simply can’t imagine not writing.

Ragnar Jónasson, 2015

About the Author

A tradition off the beaten track: The crime novels of Ragnar Jónasson

The first decade of this century was marked by a rise in crime in Iceland. Even though the alleged economic boom had proved to be short-lived, there was a genuine surge in popularity of the crime story, reaching a certain high point with the address by Arnaldur Indriðason at the opening of the Icelandic pavilion at the 2001 Frankfurt Book Fair, at which Iceland was Guest of Honour.

Following in the wake of the success of Arnaldur Indriðason’s books, the Icelandic crime novel went from strength to strength, probably because both publishers and the public realised it was possible to write good crime stories in a country that is generally regarded as being relatively crime-free. Even though most Icelandic crime novels draw on the well-springs of social realism, this does not mean that they have to contain brutal realism or a dogmatic quest for true-to-life social reality – which, as was revealed in late 2008, is by no means always what it seems to be on the surface.

In fact, one of the writers to enter the crime scene only did so after the economic collapse: Ragnar Jónasson’s first book, Fölsk nóta (A False Note), appeared in 2009. Nevertheless it is set a few years earlier, in 2006, and even though he has since filled in this time-gap, it is interesting to note that for the most part he avoids dealing the economic crisis, which has received a lot of attention from Icelandic crime writers in recent years.

Besides writing crime novels, Ragnar has, together with Yrsa Sigurðardóttir, established Iceland’s first crime fiction festival, Iceland Noir (http://www.icelandnoir.com/) which was first held in 2013. Apart from its entertainment value, this serves as a venue where Icelandic crime writers can have the opportunity of comparing notes with their colleagues from abroad, and large numbers of foreign participants from many backgrounds have been a regular feature of the festival.

Fölsk nóta

In this context it is therefore ironic that Ragnar’s first novel was called Fölsk nóta, or A False Tone. This is not a traditional crime novel but rather a ‘mystery,’ which makes it difficult to avoid using the metaphor of its having sounded a new note in Icelandic thriller literature. But perhaps the note wasn’t absolutely new: there are various things in the atmosphere of this story that remind one of the books of Viktor Arnar Ingólfsson, and it is also clear that Ragnar learned certain things from classic British crime thrillers; he has translated books by Agatha Christie.

Instead of the world of toughs, slang, hard drinking and danger, what we find in Fölsk nóta is more a relaxed, almost coincidental investigation by a young man into what has happened to his father. The story begins when the main character, the young Ari Þór Arason, receives a credit-card statement addressed to his father (who bears the same name as he does); his father disappeared without a trace nine years earlier. Shortly after the father disappeared, Ari’s mother died in a motor accident in Belgium, after which the orphan boy was brought up by his paternal grandmother. Nevertheless he has done well in life, is studying Divinity at university and an unexpected meeting with a girl in the National Library seems set to bring him further good fortune.

But the credit-card statement seems to block Ari’s plans, and suddenly he finds himself obliged to try to find out what happened to his father, even though his motive is not completely clear or, as the ex-policeman Lárus says: “Tell me one thing, are you looking for your father or looking for the truth?” (100). Naturally Ari has to look into the past, in the course of which he goes over his dealings with his father’s former colleagues, members of the family and other people connected with his parents. It soon becomes apparent that things are not quite what they seem, though the reasons for this are only revealed near the end.

The seasoned reader will probably realise what is going on fairly quickly, but this does not detract from the fact that this is a good read. Shifts backwards and forwards in time – and a trip to London – work well, and the portrait we are given of a rather lonely young man is interesting and clear; instead of exaggerated feelings, we are shown the effects that a shock such as the loss of his mother and his father’s mysterious disappearance have had on this individual and his life. In this way, the story can perhaps be seen as a sort of study of how one has to tackle the past in order to be able to move on into the future – in the course of Ari’s investigation it becomes clear that he has not kept up much contact with the people who are connected with his past and his parents. To this extent the story resembles Agatha Christie’s crime novels, which are to a large extent studies in personality – and are based on the assumption that everyone always has something to hide.

Fölsk nóta demonstrated convincingly the many-sided potential of crime fiction. Since writing it, Ragnar has kept to the more traditional tracks in the genre.

Siglufjörður

Fölsk nóta was well received, and Ragnar continued with confidence. Realising that he has a talent for solving mysteries, Ari, the main character in Fölsk nóta, makes a new start. He abandons his Divinity studies and signs up to police academy. At the opening of the next book, Snjóblinda (Show Blindness, 2010), he has set up home with Kristín, the girl he met in the National Library. He has completed his studies in the police academy and is looking for work; she is completing her studies in Medicine. There is turmoil in their relationship when he announces to her that he has accepted a policeman’s position in Siglufjörður without consulting her first. In this we are reminded that Ari is a loner who is obviously not used to having to take other people into consideration. This results, to some extent, from his unusual family history, though it also answers well to a feminist-critical approach; Icelandic literary critic Helga Kress’s analysis of Laxdæla applies here: the man assumes he has complete freedom to travel and simply expects the woman to wait for him.

Ari is therefore feeling wounded when he arrives in Siglufjörður, in addition to which the he finds the deep winter snow there menacing; Ragnar succeeds in creating an atmosphere of foreboding in this peaceful village gripped by the forces of nature. Naturally it is not just the weather that is menacing: it soon emerges that not all is as it seems in the village. An elderly, well-known writer is found dead at the foot of a staircase, and it seems that he fell while not fully sober. Ari’s superior, Inspector Tómas, finds this explanation perfectly reasonable, but the new police officer is not so sure. ‘He obviously fell backwards [...]. That could indicate that he was pushed’ (89). The writer had been working in the local theatre where rehearsals were in progress for a show in which many of the villagers were involved. A few days later a young woman is found, half-dressed and wounded, in a garden. She has been stabbed and is in serious condition. Notwithstanding Tómas’s doubts – ‘Investigate what? It was just an accident – I’m not going to turn the whole place upside down’ (119) – Ari decides to ask some questions on his own account. Which certainly does turn the whole place upside down, since news travels fast in such a small community.

Of course it turns out that Ari’s suspicions are correct but, as is generally the case in classic crime stories of this type, the solution is not immediately obvious and various complex secrets from the past come to light.

In an article on the classical nineteenth-century crime story (and hence the origin of the modern crime story), Clive Bloom defines one of its characteristics as being the creation of a separate world that is governed by the laws of the crime story; this is, above all, a fictive world that is clearly differentiated from reality even though it is set carefully within a realistic community and based on facts. (Bloom 1988)

This can clearly be seen in Ragnar’s work. At the beginning of Snjóblinda he defines his world’s relation to what was the main topic treated by Icelandic crime-fiction writers at the time: the economic collapse. When Ari first arrives in Siglufjörður he finds it a rather dead place and says to Tómas: ‘It’s certainly very quiet here [...]. That banking collapse will probably hit you in time, just as it has the rest of the country.’ The action is set in the winter of 2008-09, so the economic collapse would be a natural topic of conversation:

‘Banking collapse? Know nothing about it. Any banking collapse will stay in Reykjavík; it won’t come up here – too far to travel, mate,’ said Tómas, turning the car in to the Town Hall Square in the centre of the town. ‘The boom years passed us by up here, so this collapse won’t touch us either.’ (31-32)

He goes on to say ‘our crises come from the sea,’ – so defining the world in which the story takes place: a little coastal village off the beaten track, not just in the sense of being remote but also being untouched by the forces shaping society as a whole.

The community he describes in Siglufjörður is also is own invention, a fictional world, though it is based on certain facts about small communities. A good example of this is the theatre: amateur dramatics are popular and such theatres are a feature of many small towns and villages in Iceland. By using the theatre in his first book set in Siglufjörður, Ragnar is therefore referring to a familiar phenomenon, though at the same time we can see the theatre as a sort of symbol of the fictional world that is the community in which the story takes place.

Ragnar’s third novel, Myrknætti (Dark Night, 2011), takes place nearly two years later in the summer of 2010. The time-gap between the events of the story and its publication date is thus much shorter. The action begins when a man is found murdered outside a holiday cottage in Skagafjörður and it comes to light that he was working on the Heðinsfjörður Tunnel (which was opened in October 2010).

Tómas and Ari are commissioned to make enquiries about the man in Siglufjörður, even though the investigation is in the hands of the Akureyri police.

The village, as an entity, is very important: Tómas defines and judges people on the basis of whether they are locals or arrivals from the outside. The distinction, in terms of status, is very much to the advantage of the former. Himself an outsider, Ari is critical of this attitude and tries to view the community in a more neutral way.

The observer who stands outside the community is another feature of the classical crime story discussed by Bloom in the aforementioned article; the local police depend on the insight provided by the detective from outside their number. It is in this role of the outsider that Ari sees various things that are invisible to Tómas, the home-grown policeman, simply because Tómas is incapable of seeing his own community objectively. Nevertheless, Bloom stresses that even though the detective is an outsider, he must be fully compatible with the community; he must be completely normal. This applies to Ari, who is presented as a perfectly typical young man, right from the first book. We sense this in his weaknesses: his initial lack of direction, his insecurity regarding his position in Siglufjörður (he cannot abide the nickname he is given, the preacher, because he has been studying theology) and how he messes up his relationship with Kristín.

Then another ‘external’ investigator becomes involved in the case: this is Ísrún, a journalist who decides to look into the murder case. She works on the newsdesk of the National Broadcasting Service (RÚV). She discovers that the owner of the summer cottage has a skeleton in his cupboard. She also finds out, when she arrives on the scene, that the victim was not the innocent figure he appeared to be at first: even though he was involved in charity work, his ex-wife and others who knew him have some rather negative things to say about him. Ari also discovers the same thing, and the investigations made by the two of them overlap at various points though without their ever actually meeting. The ramifications of the case extend in various directions, including back into the past of one of the people of Siglufjörður.

Personal matters play a larger role here than in Snjóblinda: in addition to Ari’s heartache, Tómas is undergoing difficulties because his wife has moved to Reykjavík and is starting a course of studies there. A third policeman, who has played a minor role up to now, is also a bit absent-minded. In Snjóblinda it was revealed that he had been a nasty kid who led bullying when he was young. As an adult he has done his best to make up for his misdeeds, but now it seems he has not been able to make amends for one of them and he has a burden of guilt – which is kept alive by anonymous e-mails.

Ísrún’s role is also much larger than might be expected at first, and one has the feeling that a new major character is being introduced here: she plays a large part in the book and is connected with the case in an unexpected way. Ísrún returns in the next book, Rof (Rift, 2012); she does not appear in Andköf (Gasp, 2013), but makes a brief appearance in Náttblinda (Night Blindness, 2014).

Héðinsfjörður

In his fourth book, Rof, Ragnar uses the opening of the Héðinsfjörður Tunnel to create an even more remote scene of action. The plot involves events from the distant past at a point in Héðinsfjörður which is suddenly made accessible to traffic following the opening of the tunnel that runs through the mountains on both sides of the fjord. Not only is the setting remote; the crime is also an old one:

Ari Þór Arason, a police officer based in Siglufjörður, had no real explanation of why, now that the tiny community is in the grips of a terrible situation, he decided to take the time to examine an old criminal case for someone he scarcely knew.

The man, whose name was Héðinn, had phoned Ari shortly before Christmas [...]. Asked if he had time to look into an old case – the death of a young woman. (15)

The terrible situation referred to above is an epidemic brought to the village by a foreign tourist: ‘Shortly after the tourist died, the unusual decision was taken to place the tiny village community in quarantine’ (16). Naturally, people are afraid, and the police have to do their duty. ‘Ari hoped that Héðinn’s visit might make him think about something other than this damned epidemic’ (17). The isolation is thus twofold: as regards the fjord itself and as regards the quarantine in which Ari is confined; Héðinsfjörður lies within the quarantine area.

As has been mentioned, Ísrún plays a large part in the story; she is investigating a case in Reykjavík which also proves to have a dimension in the past. A young man is knocked down by a car, and there is a suspicion that this was intentional. He is thought to have died immediately, but as he is the son of a prominent politician, the case arouses a lot of attention. Dissension within the father’s party comes into the story. Ísrún is also given the task of covering the quarantine in Siglufjörður and for this reason she phones Ari:

He didn’t often watch the news but he knew who she was and had occasionally seen her reporting on the odd crime cases. He had also read an interview with her in one of the weekend papers after she won an award for investigative journalism about the Skagafjörður human trafficking case that he and Tómas had had to do with about a year previously. (54)

The two cases are not related except insofar as Ari asks Ísrún to help him with his case; she responds readily so that to some extent they are again working together. Ari’s case is the larger one. In addition to the prevailing isolation, there is a suggestion that something strange was going on at the farm in Héðinsfjörður where the young woman died. Two couples had been living there: sisters with their husbands. A young man also worked on the farm for a time and a female photographer had visited and taken some photographs. Ari soon realises that the case is much more complicated than it seemed at first sight, and although the solution does not come as much of a surprise, it is well-crafted and interesting.

There is a certain atmosphere of calm in Rof, and the author puts the feeling of isolation to good use. The menace of the snow in Snjóblinda is transferred to the classical rumour of haunting on the farm in what used to be a very isolated part of the country. The result is a striking and memorable portrayal of a situation that is very different from that of the earlier books.

Changes have also taken place on the domestic front: Ari and Kristín have at last resumed their relationship, two and a half years after he moved to Siglufjörður. Therefore, the story presumably takes place in 2011. Tómas has taken a few months’ leave so as to explore the possibility of reaching a truce with his wife, and is enjoying the break – and Ari foresees promotion, though he is not quite sure whether he will be pleased. He fully deserves it, however: we are made aware that notwithstanding his shorter experience, he is a more capable detective than Tómas, another point identified in Bloom’s analysis: the newcomer is the most capable investigator, despite being a perfectly ordinary person. Ari’s ordinariness is stressed again and again: he eats dried fish, makes a mess of his love life, slips on the ice, wants to have a son, etc. His talent lies in not letting go of something that he has set his mind on.

The past and its baggage

The past – in fact not so distant – and the present, in the form of corrupt politicians, are contrasted in Rof. The past, in opposition to the present, is also a theme in Andköf. As in Rof, Ragnar exploits monotony and isolation to the full. Close to a lighthouse in Kálfhamarsvík, near Skagaströnd, there is a big house with a dramatic history. A young woman is found dead below the lighthouse, and at first it is believed that she has committed suicide, but something does not quite fit. Tómas has been transferred to Reykjavík; Ari is still in Siglufjörður, though he has not yet been promoted to the position of Inspector. It is four years since he moved to Siglufjörður and he is still unsure of his position and future plans. Christmas is coming and Kristín is eight months pregnant. This all makes him think about the past and his parents, but he is not alone in this: Kristín is also browsing through old diaries. The whole book therefore contains a complex treatment of the past and baggage from the past in the present.

The occupants of the old house near the lighthouse are an old couple who for most of their lives have been servants to the house’s wealthy owner. The dead woman was visiting there after many years away; when she was a child, her mother and sister died near the same lighthouse. The sister’s death was said to be an accident; the mother’s, suicide.

As expected, various things come to light: another death occurs, and there are so many skeletons in so many cupboards that you can hear the bones shaking as you turn the pages. Ragnar makes even more use of mystery and foreboding than he does in Rof. The atmosphere is oppressive and loneliness and isolation are dominant themes. This mood is developed in short and vivid scenes like this one, which comes early on in the story when Ásta, who is later found dead, arrives at the house by the lighthouse:

A sudden gust of wind sent a shiver down her spine and she looked round quickly. The loud whispering in the wind had, for a moment, created an uncomfortable feeling that someone was standing behind her.

Ásta looked round for the sole purpose of convincing herself that there was no one there.

All she could see was the darkness. She was alone; her footprints were the only ones in the white snow.

It was too late to turn back now. (15)

Tómas is sent up north to investigate and has Ari to assist him; in Andköf it is made clear that Tómas has benefited from Ari’s talents in solving crimes. The theme of the incompetent and lazy superior and the clever and resourceful subordinate is a staple in crime fiction and goes back to the classic thrillers. In the old stories the detective is usually omnicompetent, while the police are ham-fisted and hidebound; the relationship has been varied and exploited in different ways in more recent writing.

It should be stated, though, that there is no bad feeling between Tómas and Ari, and thus their dealings with each other is more reminiscent of the classic crime story than of the newer versions where political corruption and red tape are serious problems. Setting the stories outside the urban environment is also in line with earlier traditions: small villages or isolated communities were also popular with Agatha Christie. All of this shows how Ragnar draws on the tradition, while at the same time moving into more modern areas.

Náttblinda (Night Blindness) follows the same pattern to some extent, with Tómas brought in to assist Ari, this time on a case in Siglufjörður. Ári’s new superior is found shot dead near a remote abandoned house. As before, Tómas is keen to proceed cautiously where the locals are concerned; he is keener to turn his attention to people from outside, and as before, corrupt politicians are involved.

It soon comes to light that there are actually three plots in this story, with points of contact between them. Firstly there is the murder of the police inspector which sets the whole business going; into this is woven Ari’s curiosity regarding the history of the isolated house where a man once died after falling from the balcony. It comes to light that the house is used as a base for drug trafficking; some prominence is given to negative social changes in Siglufjörður following the opening of the tunnel: what used to be a peaceful little village is now on the beaten track, so to speak, with increased tourism and many other changes.

The third plot involves the assistant to the mayor, another outsider who is fleeing a violent cohabiting partner. Themes of love and marriage are present in this story, as in its predecessors: Ari’s relationship with Kristín is jeopardized by his temper and stubbornness. At the end of the book there is an indication that Ari is about to leave Siglufjörður; Tómas urges him to apply for a position in Reykjavík.

Hulda

The position of women, and violence against women, are frequent themes in Ragnar’s books, as can be seen particularly in Myrknætti and Náttblinda. They are even more prominent in the next two books, in which Ragnar makes a new departure and introduces a fresh character, based in Reykjavík. This is the policewoman Hulda Hermannsdóttir. In Dimma (Darkness, 2015) she is about to retire and is rather nervous about the prospect; things are not made any easier for her when her superior, a much younger man, ‘offers’ her the chance to leave the service even earlier than scheduled because he needs to make room for an aspiring young man. Hulda has two weeks to wind up all her cases, and it is made clear to her that she needn’t put much work in during this time.

She is, however, dedicated to her job and when she is given a free hand she decides to attend to a ‘cold’ case which is hardly even a case: the disappearance of a Russian girl. She knows that the policeman who was on the case handled it badly and also that the disappearance of an asylum-seeker is not regarded as a priority. Naturally, various things come to light when she starts her investigation, both regarding the case and Hulda’s own position within the police.

Thus, there are various themes running here: in addition to the position of women in the police and the position of asylum-seekers in Iceland, gender-based violence also rears its head. At the outset, Hulda is investigating an attack on a child molester. The mother of one of his victims has confessed to Hulda, admitting to having run the man down in a hit-and-run car attack. Hulda nevertheless decides not to act on this confession.

Dimma is short and rather lean; there is little in the way of descriptions of landscape or needless detail or repetition. The plot unfolds smoothly, but there are various surprises near the end. In many ways it could be described as a meditation on crime rather than a traditional crime thriller, and in this it calls to mind Ragnar’s first book, Fölsk nóta.

Hulda is still the main character in Drungi (Gloom, 2016), where we first encounter her in her late 30s, a policewoman with plenty of experience who thinks she is on the way to promotion but bumps uncomfortably into the infamous ‘glass ceiling’. The year is 1987. A young girl, Katla, is found murdered in a holiday cottage in the west of Iceland. Hulda’s colleague Lýður, a young man on the fast track oblivious to the annoyance of a glass ceiling, solves the case rapidly and arrests the girl’s father. The man then hangs himself while in custody.

Ten years later, some friends of Katla’s decide to spend a weekend in a fishing shack on one of the islands in Vestmannaeyjar (also called The Westman Islands, an island group off the south coast of Iceland). Benedikt, the young man who was with Katla in the holiday cottage ten years earlier, is the one who gets the group together. Besides Benedikt, it consists of two girls, Alexandra and Klara, who were Katla’s classmates, and Katla’s younger brother Dagur.

The trip turns into high drama: Klara is found murdered on the island and it is evident that the murderer is one of the group. It is also clear that there is a connection between the two cases. Hulda, who is working on the case, is constantly interrupted by her superior, Lýður, who wants to have a hand in things because he closed the case on Katla’s murder a decade previously. Hulda’s investigation brings various things to light that were not known in the investigation of the first case, and the whole matter proves to be complicated – and simple.

Hulda herself is completely changed. While she still enjoys the work itself, she is bitter because her career has stagnated while younger men shoot past her on the way up. She is also plagued by grief: her daughter Dimma and her husband both died within a short time nearly ten years ago. She is therefore very much alone, and also appears to have virtually no friends.

There is more energy in Drungi than in Dimma. The focus switches quickly from one character to another, building up the pieces of the puzzle that gradually fit together. As before, it is the characters and the dynamics between them, and not least love motives, that play the key roles; the family is a central concern to Ragnar here as in his earlier books.

The story of Hulda herself is woven into both books. Her surname, or rather patronymic, Hermannsdóttir [the name Hermann literally means ‘warrior’ or ‘soldier’] is one that she shares with many others of her generation: her father was one of the British or American soldiers stationed in Iceland during the Second World War. In Dimma we are given a glimpse into how she grew up; her mother’s parents were not pleased at the arrival of the baby and the mother was forced to leave her in a crèche while she worked every minute that she could. Thus, Hulda did not enjoy a loving atmosphere, and this has marked her for life. In this, she is similar to Ari, who lacks the background of support that a family can give and who also has a tendency to cut himself off and seek solace in endless work. In Drungi she plucks up her courage and decides to try to find her father; her mother has recently died. She flies to America with information about two men, each of whom could be the man.

Thus, there are various things that connect these two main characters in Ragnar’s books. He succeeds well in including elements of personal life in his works without them taking up too much room, yet in a way where they tell their story and can also have a bearing on the crime story in various ways.

úlfhildur dagsdóttir, November 2016

References

Bloom, Clive, “Capitalising on Poe‘s Detective: The Dollars and Sense of Nineteenth-Century Detective Fiction,” in Nineteenth-Century Suspense: From Poe to Conan Doyle, ed. Clive Bloom, Brian Docherty, Jane Gibb and Keith Shand, Houndsmills and London, Macmillan Press 1988.

Awards

Nominations

2024 - Storytel Awards: Reykjavík (with Katrínu Jakobsdóttur)

2023 - Blóðdropinn, hin íslensku glæpasagnaverðlaun: Reykjavík (with Katrínu Jakobsdóttur)

2021 - Storytel Awards: Hvítidauði (White death)

2020 - Storytel Awards: Þorpið (The Village)

2019 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Þorpið (The Village)

2018 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Mistur (The Mist)

2017 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Drungi (The Island)

2016 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Dimma (The Darkness)

2015 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Náttblinda (Night Blindness)

2014 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Andköf (Chocking)

2013 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Rof (Rift)

2012 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Myrknætti (Dark Night)

2011 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Snjóblinda (Snow Blindness)

2010 - Blóðdropinn, The Icelandic Crime Fiction Prize: Fölsk nóta (False Note)

Hvítalogn (Cold Calm)

Read moreElín S. Jónsdóttir, frægasti glæpasagnahöfundur þjóðarinnar, er horfin, sjötug að aldri. Verk hennar hafa notið mikillar alþjóðlegrar hylli en undanfarin tíu ár hefur hún haft hægt um sig. Lét hún sig hverfa eins og hún gerði eitt sinn fyrir mörgum áratugum – eða hefur einhver gert henni mein?. .

Reykjavík

Read moreÍ ágúst 1956 hverfur ung stúlka, Lára Marteinsdóttir, úr vist í Viðey og eftir það spyrst ekkert til hennar.

L'île au secret

Read more

The mist

Read more

Sneeuwblind

Read more

Schneetod

Read more

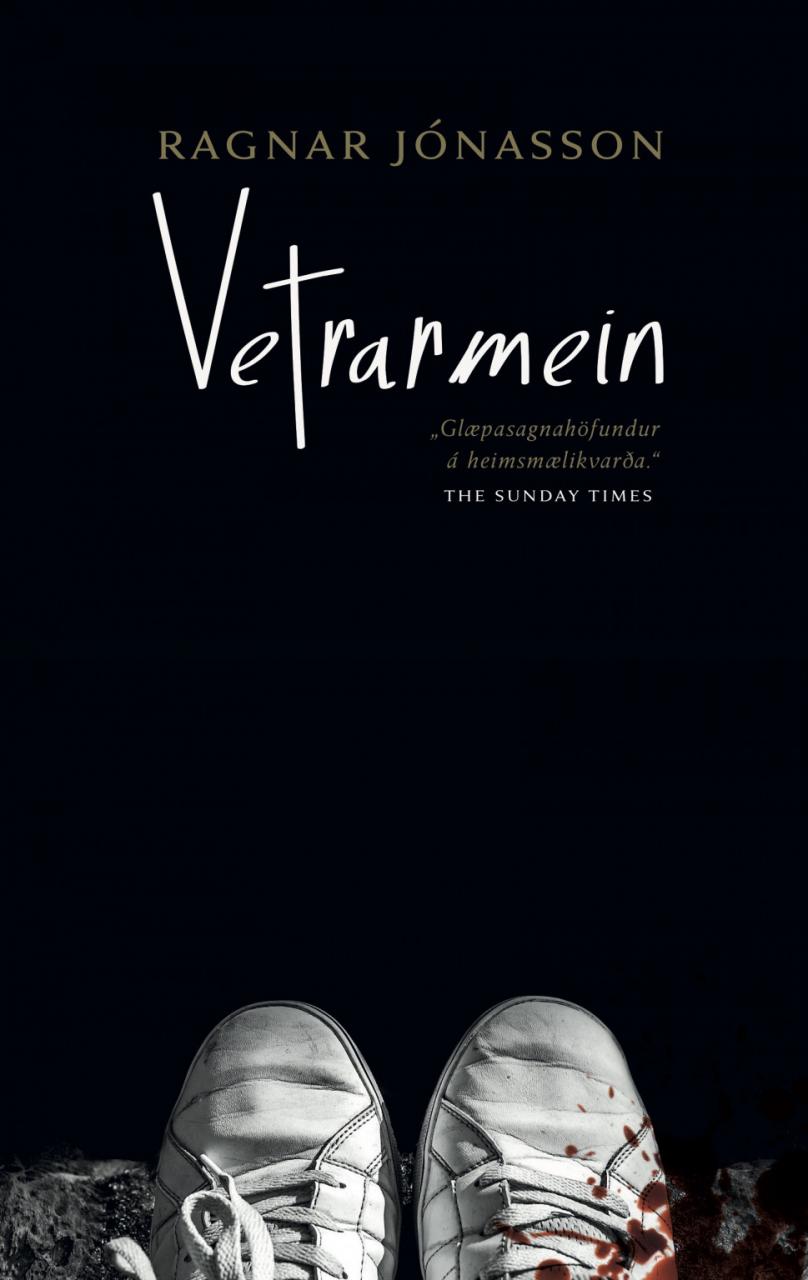

Vetrarmein (Winter's Wound)

Read more