Bio

Steinunn Sigurðardóttir was born in Reykjavík in 1950. She finished her Matriculation Examination at the Reykjavík Higher Secondary Grammar School in 1968 and a BA in Psychology and Philosophy at the University College in Dublin in 1972.

Sigurðardóttir was a reporter at the Icelandic National Broadcasting Service (RUV) and a news correspondent with intervals from 1970-1982. She has also worked as a journalist and written programmes for radio and television. Steinunn Sigurðardóttir has lived for long and short periods of time in various places in Europe, in the US and in Japan. She currently divides her time between France and Iceland.

She published her first book, the poetry collection Sífellur (Continuances), 19 years old and received immediate attention. She has written novels, poems, short stories, plays and biographical books.

She has received many recognitions for her work, such as The Icelandic Literature Prize, for the novel Hjartastaður (Place of the Heart) in 1995 and for the novel Ból (Lavaland) in 2023.

Her books have been translated into other languages and a French movie based on the novel Tímaþjófurinn (The Thief of Time) premiered in 1999.

From the Author

Three Short Stories About Fiction: Steinunn Sigurðardóttir on Herself

Sometimes an author is asked: What is the central theme in your work? With me there are few answers since the worlds I live in are more than two and not alike, a world of a relatively objective narration and a completely subjective world for example, a world of prose and a world of poetry. Some connecting themes must however be visible in books by the same author. I myself have a problem tracking them, but I can give hints. TIME would be one of them.

TIME in my work is in some ways connected to Icelandic nature and its seasons. Icelandic time is forever mournful, it’s even worse to catch up with than other times, it is regret at the summer that passed without the chance to grasp it, anticipation of the spring which never seems to arrive, anxiety for the winter that lasts most of the year.

The Danish poet Henrik Nordbrandt maintains in one of his poems that there are 15 months in the year. He recites the months and ends with: November, November, November. Time in Iceland behaves differently. An old farmer from my part of the country says there is one month missing in the year, between May and June. The month that is missing might symbolise the occupation of writing books—perhaps those who write feel there is something missing. Who knows whether the act of writing isn’t an attempt to fill the endless spaces—to make the invisible visible—to add a month to the year, in case it should be missing. The tragedy in an author’s life is thus not his failed works (which they probably all are, in some way) but those that will never be written, and don’t exist anywhere but in his mind, as an idea, one sentence, a short story, or simply a title. All the dream titles I will never be allowed to use for all the works that will never be written. Over them I could cry.

If I could be born again I would want to be a writer, gladly a female writer, but much rather sexless or multisexual, and be allowed to write a fraction of the works I had left unfinished in this life. And continue thus—on and on.

ooo

Writing poetry and writing novels has very few things in common, other than perhaps to be a rebellion, introvert and extrovert. It is a challenge to yourself, to the society; with a novelist it is often joke, made no less about oneself than others, a distortion of oneself. When Flaubert says he is Madame Bovary, I take him literally.

A novelist uses himself to the utmost and digs into himself for the things he needs each time. The reader often sees himself in the parts that originate in the author but not in models on the streets, and not even in the reader who thinks he can be a model, even in the literal sense of the word. One of the things a novelist can hardly avoid joking about are the people of his own country. His critical eye must see something wrong with various things that are best dealt with humorously. It is here that novelists of small nations are skating on thin ice. A Frenchman or a German can make jokes about his own nation. A big nation finds it humorous and well deserved. But if an Icelander or an Irishman does the same the people are not amused. A small nation can’t stand to see itself in a distorting mirror, because it is filled with a combination of a boiling inferiority complex and dormant delusions of grandeur. It can’t stand to see mythological ideas about itself overturned.

Poems are a different matter altogether. I haven’t really much to say about them because they are so rooted in me. But I’m glad to have started with poetry, to have a place there, glad to have partly kept to them. At least I don’t have to live with being a frustrated poet, as some novelists claim to be, including Faulkner.

In the poem I’m on my old home ground and get to deal with my delightful form—save a word and another, cut out, find a new and better word, always a new one, until finally a decision is reached. Then it’s fun. But I don’t write poetry unless I’m in the mood. Prose you can write no matter how the wind blows in your soul, it is a job that can be approached like any other office work.

ooo

Words have been my toys for as long as I can remember. I was less than two years old when poetry began to thunder on me. Guests didn’t leave their part unfinished, there was singing as well, and the sport was to learn this as quickly as possible, quatrains, maxims, hymns, patriotic poems, and preferably to teach it immediately to others, if I was able to find a victim. However, it was not known where such a young child learned combinations of dirty words which it uttered to see how the grown ups would react.

Words weren’t just toys but playmates as well. I had a playmate who lived in a crackling radiator, I sat on the floor and talked to him for long stretches of time; he was an invisible partner made of my own words and daydreams. Borges says that the writer is a daydreamer. I find that beautiful, and perhaps it’s even true.

I learned to read accidentally when I was four years old, by following my brother to reading classes. I became an omnivorous reader which wasn’t a unique incident in the town. In Reykjavik in those days the only pastime was reading and swimming. I thus grew up mostly in the City Library at Thingholtsstraeti and in the old swimming pools at Laugardalur and in the buses that travelled between these places and my home. Throughout my childhood my head was soaked in a strange mixture, Count Basil, Morgunbladid, Halldór Laxness and Tom Swift, and the toes soaked in water.

When I was six I heard a monologue performed on the radio. I became fascinated by this form and the actress’s whispering voice. Then I got on my feet and used a monologue as an act at a birthday party. This became popular and a standard at a few birthday parties in a row. Thinking back, a logical continuation of the monologue with the radiator. Not long after I wrote a play the kids in the neighbourhood were going to perform in our garage. The play never opened. One of the girls’ mother got hold of the script. She felt there was too much cursing in it, so she forbade her daughter to participate in the production. This project was thereby ended. My first work that was supposed to appear before an audience was thus a prey to censorship.

When I was thirteen or fourteen years old I started writing poetry, dark and romantic. At least that’s how I remember it. All the poems are lost, unless I was so provident as to throw them away. In the days of the first poems storms reigned in the soul. In between, gloominess took over. Then whole days were spent in my room with feet on a desk. The same desk the poems were written at when the gloom could be activated. The same desk the poems were hidden in, closed and locked inside, until the time I put them together in a manuscript and they were published in a book. That’s why for years writing poetry was for me a sort of a secret rite, locked with a key in drawers, beneath stacks of paper. The key then carefully hidden. I had no confidant who I showed the poems to; I would have been greatly ashamed of them in front of others.

It is appropriate for a writing career to begin with secrecy. To write is in some ways about hiding, about the interplay between hiding and revealing. It is so important not to show everything, not at all to show everything. The game of hide-and-seek is one of the things which makes writing so exciting, and reading, hopefully. But it is also dangerous for the author, because it is easy to destroy a book by too violent evasions in the game.

The title of an author didn’t occur to me about myself when I was younger, and I was opposed to that label even long after I was well into the public literary world. The touch of rebelling against being what I always was is especially funny considering that meanwhile I arranged my life very carefully around writing. Thinking back, I am not unhappy with this rebellion. It is of course very nice to write if you want to, but the stance of him that writes changes once the dices are rolled and he is a published author. Perhaps this touch of rebellion has helped me in being a relatively mobile author for relatively long. I mean, who wants to get stuck in the sculpture of an author at his desk?

Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, 2000.

Translated by Jóhann Thorarensen.

About the Author

We have two articles on the works of Steinunn Sigurðardóttir.

The first, "Self-Portraits in Time" is written by Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir in 2000; the latter, "From Soul Love to Systa's Side", is written by Guðrún Steinþórsdóttir in 2021.

Read the earlier article below or click here to view the more recent article, "From Soul Love to Systa's Side".

Self-Portraits in Time: The Works of Steinunn Sigurðardóttir

Now my soul is the only Icelandic spook

that is left alive, if life is the right word.It preys on sheep and maddens farmers from Eyjafjordur.

No one is amused when the spook neighs

and jerks around the valley clutching half a sheep.Determined to come back and back.

This she-ghost of Sigurðardóttir is not yet beaten as the soul in the opening stanza of the poem “Self- Portraits at an Exhibition” from 1991. On the contrary, determined to reappear again and again, like the she-ghost, the writer’s soul is a giant in Icelandic literature. It is neither finished nor a staggering “midget walking behind with a little cane/inconsolable in a one man’s funeral procession,” as is stated in the final stanza of this poem.

Steinunn Sigurðardóttir published her first book, the poetry collection Continuances (Sífellur, 1969), when she was 19 years old and attracted attention immediately. Two other volumes of poetry There and Then (Þar og þá, 1971) and Traces (Verksummerki, 1979) followed and in 1981 and 1983 she published the short story collections Tales Worth Telling (Sögur til næsta bæjar) and Fictions (Skáldsögur). Sigurðardóttir wrote two plays for television, A Physical Contact in the North Part of Town (Líkamlegt samband í norðurbænum, 1982), based on a story in Sögur til næsta bæjar, and Pink Ribbons (Bleikar slaufur, 1985). The movie was a natural medium for her in the early eighties since Sigurðardóttir wrote cultural programs for the national television that aroused great attention. Apart from that Sigurðardóttir has written a biography of the Icelandic president Vigdís Finnbogadóttir and translated novels and plays.

Just as Sigurðardóttir’s art forms are many and diverse so the self-portraits in her texts are many and varied; of all ages and of both sexes as in the long poem called “Self-Portraits at an Exhibition” where the poet shifts from one image to another. And thanks to the Icelandic language the interesting situation appears where even though the self-portraits are masculine—a midget in the opening and closing stanzas, a weatherman in one place and a fallen angel in another—the soul or the self-portrait is always feminine; a woman trapped in a man’s body who, without exception, rises in a little private rebellion like the weatherman whose predictions are no longer completely correct:

But suspicions arise at the headquarters

when the weather forecast is thunder and lightning

for two days without stopping.Then people realise: now the soul is in a head-spin

and the district physician is put on the case.

In this manner a rebellion is hidden in a language like a female soul in a man’s body; or is this soul perhaps the muse itself, a sort of a she-ghost forever reappearing? The self-portrait is divided from itself at the beginning like a woman’s self from a man, dual and multiple, androgynous and many faceted. In this poem the self-exploration which in many ways characterises Sigurðardóttir’s work is clearest; the poetess takes many forms and mirrors herself in the behaviour of weathermen and she-ghosts.

Conflicts within language are prominent in Sigurðardóttir’s works where an ironic sense of self and insistent emotions wrestle and blend together. This is obvious in the poem “Self-Portraits at an Exhibition” where the ghost and the weatherman are incredibly comic figures with their sheep’s quarters and their incorrect weather forecasts but underneath a well of emotions is boiling. Not only does the weatherman give a wrong forecast but thunder and lightning “for two consecutive days.” Thunder and lightning is one of the classical metaphors of a spiritual tempest that is given new form here: the agony of a female soul in a weatherman’s body. It is precisely in such ironical word games that Sigurdardóttir’s talent is best portrayed, as we can see in her prose works. The control of language, and the conflict within it, give Sigurðardóttir’s poems and prose power and daring.

Sigurðardóttir’s first novel, The Thief of Time (Tímaþjófurinn, 1986) is heavily situated in the middle of the upset of postmodernism. The approach is different from the short story collections both concerning the subject matter and the use of language. It is here that Sigurðardóttir’s command of language and her wrestle with it reach its peak. A poem slides into a story and the story spreads itself in order to embrace the poem and in this cradle Alda (which means “a wave”), the heroine of Tímaþjófurinn, is rocked. With this book Sigurðardóttir became a success gaining the public’s praise as well as the admiration of critics.

Tímaþjófurinn is a love story pierced with a poem. Though not just a love story but much rather a story of separation. The love affair itself lasts a short time but the pain, the mourning, and the feeling of rejection is what is left behind. Alda, a woman of a good family and an elegant teacher in junior college, falls in love with a young colleague and together they have a hundred days of extreme passion. But then it is all over. With cold deliberation Anton, the lover, sentences the relationship to death and the greater part of the book is centered on the deserted Alda, rootless in the sea of broken hearts and memories. This theme of separation has come up before in Sigurðardóttir’s poems and does so again in the novella The Love of the Fish (Ástin Fiskanna, 1993). In Tímaþjófurinn it becomes clear that the theme of separation is also a self-exploration, a search for a(n abandoned) self, similar to the poem “Self-Portraits at an Exhibition” five years later. In Tímaþjófurinn two Aldas are tossed about: the heroine Alda, who has reserved a safe place in the old cemetery; and her other self, another Alda, who is already buried in the cemetery, a stillborn sister and the namesake of Alda the heroine. We see this dual self-image for example in the body, the body language. On the one hand we have the face, the surface and the visible, and on the other hand we have the turmoil underneath, the emotions that are like disgusting intestines which you can never show because:

A person who doesn’t keep a straight face is not only naked but also open and the disgusting intestines are to be seen. No one can stand another after such an insight, unless he is a qualified surgeon. (178).

By laying bare her feelings Alda makes her body open to decay. Her body betrays her after the separation, Alda’s body literally breaks down like the love affair, she gets a bad hip and loses the ability to speak. Symbolically it is her dead sister’s mortal and rotting body that takes over Alda’s elegant living body. The separation is from herself or, to be more exact, from the glamorous image which “is very carefully arranged, each hair sculpted in the right place, in the red knitted dress that cannot conceal the perfect sculpture of the body” (25). The body is seen as a sculpture, a statue, an image but not as real mortal flesh. Seven years later Alda avoids Anton, does not want him to “find out how damaged she is” and smile “sympathetically with her aged self.” She “goes senile in the hip and supports herself with a cane” (186). In the body the theft of time is obvious, Anton steals Alda’s youth and beauty and she ages in absolutely no connection with the calendar.

The language is used effectively in Tímaþjófurinn and the presentation itself is no less important than what is being presented, words woven into incidents just as incidents are woven into words. One example is when Alda shows her lover the flower she so caringly nurtures, a flower which by its name “Impatience” symbolises Alda’s love for Anton. From the description of “Lísa” flowers in bloom in the window the text flows into a flowered love:

Lísa, which is called Impatience in foreign languages ... flowered manifold around the time when the sun’s course was the shortest. Stunned, Christmas teddy looked at a hundred reddish-pink Lísa flowers. Thought I couldn’t do this, like he said.

My love started to bloom in here

and surpasses others in the window

with eighteen flowers and all kinds of buds.

How fair is your flower, my guests say

and don’t know this is love. (47-8)

Here a familiar metaphor is transformed into an original declaration of love, where flowers and floral metaphors are woven into descriptions of love and impatience. The impatient Lísa is, like Alda, impatient for love and in a modest way we have here an echo of the Song of Solomon from the Bible; in Icelandic the line “Lovely is your flower, my guests say” carries with it a rhythm such as “the saviour of thy good ointments” from the Song.

The novel The Last Word (Síðasta Orðið) was published in 1990 and it is a highly comic parody on Icelandic society as it appears in the very special Icelandic obituary-culture. Neither did Sigurðardóttir abandon the poem and in 1987 she published The Potato Princess (Kartöfluprinsessan) and in 1991 Cow Dung and Northern Lights (Kúaskítur og norðurljós).

The novella The Love of the Fish (Ástin fiskanna, 1993) is in some ways a continuation of the speculations we see in Tímaþjófurinn. The heroine, Samanta, has a brief love affair with a man but she then decides to end it and runs away from both him and love.

Here Sigurðardóttir draws on the world of fairy tales and places her main characters’ first meeting in a castle where peacocks wander around the garden. “I think of when we first met and I was in the incredible position of living in a castle and two peacocks were my companions,” says the “princess” Samanta. But the fairy tale does not end in the traditional manner with a promise of everlasting marital bliss. Ways part and the woman discovers that the ending of fairy tales is not to be taken for granted:

I understand when I listen better that it is not to be taken for granted that she who sends her loved one alone up north will reap an everlasting separation, even though it’s my story. I understand now that she who sends her man alone up north could just as well gain from it his long fellowship. No one knows, however, on what the outcome is based, except it is what song the bird sings once the man has sat down on a rock by the Norðurá River.

It is Samanta who takes her destiny into her own hands and rejects love contrary to Alda who lost in the turmoil of emotions.

Sigurðardóttir’s heroines become stronger and more powerful with every book; just as the reappeared she-ghost that will not be beaten Sigurðardóttir’s heroines grow more forceful with every new image. In Sigurðardóttir’s next book, Heart Place (Hjartastaður, 1995), she forms a circle of strong and independent women who take on a highly symbolic journey into the past and nature so as to gain control of their lives and make peace with their image of themselves.

“You are enormously superstitious” the changeling Edda Sólveig says to her mother Harpa Eir who desperately tries to see a sign of luck in rainbows and Egyptian insects. Both are symbols of regeneration and rebirth and thus fit the theme of change and shape shifting, the main thread in the novel Hjartastaður. The story is a travel account in more than one sense. There is travelling both in time and space; the journey of three women to the eastern part of the country is also their journey back in time, an attempt to rediscover the innocence of youth and the peacefulness of the places of their childhood; and the third journey is a journey into the history of the country, into the folktale where changelings wander freely and wonders happen; just as the father of eighteen in the land of the elves rebounded into his former life by amazement, the problem child is to be driven back into its problem free childhood by the wonders of country bliss. But not only is the daughter a changeling, so is the mother. Harpa Eir calls herself the first immigrant; un-Icelandic in appearance due to an alien father she is not only uncertain about her origin but unstable in the role of a mother, a child that has a child and therefore changes too early from a child into an adult, a single mother. Apart from the changeling name, she calls herself the foster daughter of the wolves, a wild child, a bastard child, a fairy tale princess, little people and a half-breed, all pointing to the idea that she is not wholly human, not wholly Icelandic, a changeling from another world.

But the lack of origin also gives a certain freedom, “The one who doesn’t who he belongs to does not know his name,” Harpa Eir says but adds that “he chooses whatever name he sees fit until all is discovered” (93). Those who are changelings have the possibility to reappear again and again just like the ghost in Sigurðardóttir’s poem “Self-Portraits at an Exhibition.” Harpa Eir, who has already faced so many changes in her life, has an easier time taking destiny into her own hands and changing lives again, returning back in time and space to search for a new origin, her own and therefore her child’s. This origin is in the land itself, its history and legends, just as in her own biography. About the changeling itself a whole new race of words is used, understandably since there are rapid conversions, both in the mother’s mind and in the problem daughter’s behaviour. Edda is called the “beast” just as she discovers her mother’s insect, the aforementioned clay-beetle, a symbol of change and regeneration, and, as the story and the travel progress, she starts to change into a monster, a ghost, a gorgon, a merman (who laughs), a vampire, a spectre (empowered and sent from the south), an adder and a serpent; most of them good and valid words for various beings from folklore and closer to a mythical dimension when we add the serpent. This does not, however, include all changelings because we have the third woman aboard. It is the ghost of Harpa’s mother, the one who couldn’t stand Iceland but longed for foreign countries and fell in love with a foreigner, a relationship the result of which was the changeling and the fairy child Harpa Eir. Ghosts are of course changelings too, have changed from living to dead and from there into ghosts.

Modern times are then mixed with this strong theme of folklore. Sigurðardóttir works with determination to create a certain void in time: “time is gone,” it says in one place and the road is timeless. The women are called contemporary Reynisdrangar (large rocks) on the sand, and on the slope where grandpa saw the monster as a child, the problem child and the monster Edda walks today. The changeling Harpa Eir is sent, when she is eight years old, in a sailor suit with snake curls and a navy cap to a Christmas ball and the story jerks into the present when she says about herself that in this she must “have looked like a young transvestite on an uncertain course” (54). In this way we have a constant dialogue in time, between legends and contemporary ideas. Neither is there less emptiness in space when we find in the text allusions to American horror movies alongside very Icelandic stories, an example of which are references to the movies Scanners (David Cronenberg, 1981) and The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) where a young girl is possessed by an evil demon and commits many foul deeds, but this movie has in fact been seen in the light of the drastic changes that occur when children reach puberty and how parents often feel they are stuck with a changeling. The references to both movies are highly appropriate, the story of a clairvoyance and shape shifting and the story of the daughter of a single mother that changes dramatically, as well as the fact that the whole horror movie metaphor is direct, both as a comparison to a state as well as a ballast to the present and the fact that it is in the horror genre that the legend and the myth are most exploited. Thus folklore and popular culture go hand in hand.

Surrounding this intertextuality is Harpa Eir’s own story, her biography that will never be written but constantly changes titles according to the emphasis. Of course the story is written and is in fact the story itself, the book Hjartastaður, although the title never comes up. The titles of the imaginary biography indicate the atmosphere at each time and at the same time they participate actively in the making of history and the recreation that takes place there. Titles such as Hopeless Passengers, The Girl Who Didn’t Grow Up, Half-Heartedly, Half a Man, The Man Who Runs Away from Life, and The Nasty Paramedic Under Gnúpur not only signify the many layers of history and tales that overlap in the novel but also the fact that it is always Harpa herself who writes her own story, as can be seen from the changeling’s lines above, “The one who doesn’t know who she belongs to chooses her own name.” She chooses to have the baby, at a very young age, she takes responsibility for her own life, and embarks on a journey into a past where she discovers her destiny and her origin and finds furthermore the beginning of a new life and a new story.

It is as if with every new book that secures the writer’s place her heroines become more secure and stronger, both as makers of their own destiny and as characters; once more we have speculations about self-portraits (at an exhibition).

After all those heroines Sigurðardóttir chose a man as a narrator in the novel Hanami: The Story of Hálfdán Fergusson (Hanami: Sagan af Hálfdáni Fergussyni, 1997), a story about a truck driver who thinks he is dead. In 1998 the author turned to writing a book for children and published a story called The Aunt’s Tower (Frænkuturninn).

Sigurðardóttir’s books have aroused great attention, understandably enough since they possess a very special kind of liveliness and a play on words. The theme of separation and the complex self that appear repeatedly in Sigurðardóttir’s poems and stories follow close behind thoughts about time, its nature, and uncertainty. The search for time and self go hand in hand, it is a search for the self in time, and as befits a mature writer the concept of time becomes even stronger in the two latter collections of poetry; the search for the self is different, sensed through time and space, rather than as an introverted vision. The search for time, which was stolen so effectively in Tímaþjófurinn, continues with an even stronger focus. This is well described in the poem “The Moment” in Kartöfluprinsessan, where everything is just a foreboding or an emulation of the perfect moment:

I sent forth rays

to your eyes’ dark heaven.I received their rebound

and the sounds of the words.and loved you

this obvious moment.Others were a foreboding of the One

or an emulation of it.

In the poem “Anachronisms” from the same book the minutes play and jump, they “have stopped their slow trot clockwise” and “A moment ago I saw one of them jump backwards/then forth two steps,” in defiance of the blind man “who propels the hands.” In the poem “Monstera Deliciosa on Night Shift,” from Kúaskítur og norðurljós, a sly plant tangles itself up in the clock and strangles time in a devious way:

The master shudders drowsily

as he walks to the living room in the morningFor the strange flower that Málfrídur grew best

and the clock on the wall

are all tangled up.The youngest leaf entwines itself light green around the big hand and nabs it at midnight.

This devious plant discovered a means—and strangled time.

Here the core of Sigurðardóttir’s work is to be found in a single young plant which seizes total control in a devious way. Time is masculine and fixed in its ways like the master of the house while the plant and Málfríður are women in a rebellion of tangle and midnight meetings. In this manner the poetess fixes herself in time, herself and her many faces who watch the reader in the poem “Self-Portraits at an Exhibition,” faces that change and metamorphose before the reader’s eyes, jump backward like a midget at a disco and then two steps forward as an Icelandic she-ghost or a muse. The poem without a sense of time lives on as a frozen moment in time that can be studied and investigated from all sides and is, like the she-ghost, determined “to reappear again and again.”

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, 2000.

Translated by Jóhann Thorarensen.

Poems translated by Jóhann Thorarensen and Bernard Scudder.

___

From Soul Love to Systa’s Side

Steinunn Sigurðardóttir is one of Iceland’s most prominent and respected authors and her career spans more than half a century. Over the course of that career, she has received a number of literary prizes and her works have been translated into various languages. Steinunn is prolific and versatile and is remarkable for the ease with which she repeatedly crosses between different genres and playfully mixes their various aspects. She began her career as a poet and her narratives are usually tinged with lyricism and even tend to metamorphose into poetry, the clearest example of this probably being The Thief of Time (Tímaþjófurinn 1986). This overview picks up where Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir’s article, detailing Steinunn’s works up to the year 1999, leaves off. In 2011, literary scholars Alda Björk Valdimarsdóttir and Guðni Elísson published a book on Steinunn’s works titled Have I Been Here Before (Hef ég verið hér áður) which is an excellent roadmap to the writer’s narrative worlds, both in poetry and prose.

I

Steinunn’s works demonstrate a deep insight into human nature and a dazzling narrative talent. She often plays with language, inventing countless new words, creating unexpected and original images, and using irony and humor with panache. Among common themes in Steinunn’s poetry and prose are the transience of time, love, death, obsession and the relationship between man and nature. These themes all appear in her seventh collection of poems, Soul Love (Hugástir 1999). The book is divided into five parts, the poems in each forming a poignant whole.

The first part is titled “A Few Bursts on Death and More” and contains four poems which together form a series about life and death. In this first part, Steinunn contemplates death in the context of time and memory, grieving over what once was but is now gone, never to be again, a subject matter which often appears in the poet’s works. We also see the notion that when an individual dies a whole world is lost with them.

The second part shares the title of the book, “Soul Love”. These poems are all about love or, more accurately, the speaker’s contemplation of a lost love, regret over the loved one, and fantasies of a reconciliation between lovers who, being star crossed, cannot reunite except in the speaker’s imagined world. Steinunn writes with delicacy and sensitivity about love and how thoughts of it linger even if the romance itself is over.

The third part is called “Poems from the Countryside” and, as the title implies, it is centered on nature. Steinunn often writes about Icelandic nature but sometimes uses a distancing effect to shake up the reader’s perception. The human being appearing in Steinunn’s poems is often a time traveler who views events in the light of what was, is and will be, as is clearly apparent in the last part of Soul Love, “Broken Cities”. It contains nine poems about nameless, foreign cities. In the poems, history, environment, human lives, past, love and sorrow, as well as reality and imagination, are interwoven to form an enigmatic whole. These cities of the mind could be understood as symbolizing earlier relationships and the speaker’s past.

II

Two years after the publication of Soul Love, Steinunn published a highly entertaining novel, The Glacier Theater (Jöklaleikhúsið 2001). The novel is set in Papeyri, an East Coast-village twinned with Russian writer Anton Chekhov, surrounded by majestic natural beauty and with a wonderful glacier view. The local dramatic society decides to stage Chekhov’s Three Sisters with an all-male cast. The selection changes, however, when local bigwig Vatnar Jökull gets involved. Vatnar holds the purse strings and would prefer to see The Cherry Orchard come to life on the boards. He decides to build a “glacier theater” at his own expense in honor of Chekhov and for his own aggrandizement. The novel then relates the adventures of the villagers, gender trouble and many comical events.

The Glacier Theater has a larger and more varied cast of characters than most of Steinunn’s stories. This is perhaps because it is partly about a play and often resembles that form in terms of structure, characters and plot. It could be said to be a mix of novel and theatre and the characters are constantly striking a pose as if in the middle of a theatrical performance. Otherwise, the narrative is farcical with tragic overtones. The story follows Beatrís, the prompter, who pays close attention to what goes on around her but seldom participates directly in events. As the story unfolds, however, her own personal history is revealed. She was raised by an alcoholic mother who subjects her to psychological abuse and, like many of Steinunn’s characters, she is madly in love with a man who does not reciprocate.

Unrequited love is also the subject of Steinunn’s novella, A Hundred Doors in the Breeze (Hundrað dyr í golunni 2002). It tells the story of Brynhildur who takes a short vacation in Paris. She is married to geologist Bárður Stephensen and has two grown daughters with him. This does not, however, deter her from deciding to take a lover. The narrative goes back and forth in time as her stay in the city brings back Brynhildur’s memories of her student days at the Sorbonne, where she fell head over heels for her Greek professor, who was twice her age. Three chapters relate first Brynhildur’s affair, then her love for the professor a quarter century earlier, and finally, life in Iceland with Bárður the husband. Many of Steinunn’s hallmark themes appear in the novella: love, obsession, death and time.

However, A Hundred Doors in the Breeze is not only about love and obsession but also contains meditations on environmental issues and a critique on the construction of industrial power plants in Iceland.

III

The masterpiece Sunshine Horse (Sólskinshestur) came out in 2005 and was very well received by readers. The novel is a wonderful blend of many of the themes which characterize Steinunn’s writing: love, longing, death and time. On the first page, the text refers to Davíð Stefánsson’s poem “Some Seeds” (“Til eru fræ”). The poem mirrors the narrative as it contains the core of Steinunn’s story: child neglect and its impact. The story is told from the point of view of Lilla and follows her from when she is a little girl until she dies at just over forty. Lilla grows up in a villa on Sjafnargata with her brother, Mummi. Their parents, Ragnhildur and Haraldur, are doctors who are preoccupied with their work and have little or no interest in caring for their children. The only adult who does is the German housekeeper, Magda. When she is unexpectedly dismissed, the siblings’ lives are robbed of all stability and Lilla feels compelled to take on Magda’s work, cleaning the house, doing the laundry and taking care of both herself and her young brother.

Parental neglect is shown in many ways but is most obvious in Lilla’s longing for love and attention. After Magda disappears from her life, she seeks out Nellý, a down-and-out who lives in a hovel. Nellý has a daughter who was removed from her care and their story partly mirrors the story of Lilla and her family. Lilla does not receive the love and care she longs for from her parents but imagines that Nellý is the perfect mother and that her daughter, Dór(a), is the luckiest girl in the world. Lilla longs for Nellý’s love and after Nellý’s death, Dór becomes her imaginary friend. She writes her letters, thinks about her and imagines what she might be doing and what a charmed life she must lead. It is particularly tragic that when Lilla and Dór meet as grown women, it becomes apparent that Dóra has recovered from the trauma she suffered but Lilla has not.

According to Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, Sunshine Horse can be read as a gothic novel. The gothic school is largely concerned with “the transitory nature of existence, impermanence and loss, the dangers that await us around every corner if we are not careful.” Death, impermanence and loss are everywhere in the siblings’ home; seances are regularly held there, the parents carry photos of dead lovers like fetishes, and the siblings deal with difficult circumstances by playing death games in the attic. The family home is also large and gloomy, reminiscent of houses in horror stories, and mold festers in it over time.

In this story, Steinunn demonstrates her excellent command of form and style. Not only is the subject matter arresting but the narrative approach contributes significantly to its impact. The narrative is melancholy but humor is always present, for example in various conversations between characters and in their actions. The text is characterized by lyricism and sometimes metamorphoses into a poem, which amplifies the story’s impact. The poetic description of Lilla’s death is especially striking and forms an interesting link to the aforementioned series of poems “A Few Bursts on Death and More”.

IV

Love Poems of the Land (Ástarljóð af landi 2007) is a carefully structured and compelling collection which centers on love and nature while touching on many others of the poet’s characteristic themes. In the first poem, “An Origin Poem for Eternal Beginners”, Steinunn writes about the impermanence of love and the transience of time, already grieving the end of a romance at its beginning. Love and time are often interwoven in the poet’s work, for example in the series “Poems for the Advanced”, where irony is also readily apparent. The series is wide ranging, touching on the love lives of the middle aged, the nature of sin, laziness and more.

Although Love Poems of the Land centers on love, its speakers are not as desperate as many of Steinunn’s lovesick fictional characters. It is tempting to agree with Guðni Elísson who wonders whether the speakers “have gained in experience and are therefore not as eager to surrender to passion.” At the very least, the love poems in the book demonstrate Steinunn’s ability to constantly rediscover love and surprise her readers.

The last two parts of the book, “A Prolonged Summer Dance East of the Mountain” and “The Once-Upon-a-Time Land”, are declarations of love for the land and the natural world. The poems tell the story of the first Icelander, an Irish hermit who arrives in the country long before Ingólfur Arnarson and his followers. He settles there and believes he has found paradise, the promised land. He takes a centuries long nap, has sinister dreams and then wakes up to a completely altered world in 2006. The paradise has become a desert, a disgraced land. The series partially echoes Steinunn’s earlier writing on nature conservation in A Hundred Doors in the Breeze, reminding readers of the importance of caring for nature and fighting against heavy industry.

Many themes familiar from Steinunn’s repertoire, such as love, obsession, time and death, appear in the novel The Good Lover (Góði elskhuginn 2009) but she approaches them in a new way. The story is mostly about love, the lack thereof and the relationship between a mother and son. The novel tells the story of Karl Ástuson, a 37 year old wealthy businessman and sophisticated aesthete who owns homes in Long Island and the south of France. Karl is quite the ladies’ man and has slept with 102 women. However, he does not connect emotionally with any of them as he wants to stay faithful to his childhood sweetheart, Una, and his mother who died when he was young. Therefore, his lovers never satisfy the desire of the male hero. The story starts with Karl arriving in Iceland where, after consulting Doreen Ash, a past lover, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, he contacts Una. Together, they go in search of adventure and at the end of the novel they are still together and Una is pregnant with a baby girl.

Doreen Ash is both a more carefully drawn character than Una and much more interesting. She and Karl had a one-night stand and although he dislikes her in many ways, they speak on the phone three years later and she advices him to contact Una. It is clear that their encounter had an impact on both of them, although likely more so on Doreen. She writes a book about Karl, titled The Good Lover, in which she describes their encounter and psychoanalyzes him. She calls Karl a “son of a mother” due to his close bond with his mother and his difficulty connecting with other women.

As Guðni Elísson points out, The Good Lover contains a number of autobiographical elements. The most prominent is Doreen’s nonfiction novel The Good Lover which is about Karl Ástuson and is discussed in Steinunn’s novel with the same title. This is intriguingly self-referential. In The Good Lover, Steinunn refreshes the love story form by, yet again, playing cleverly with its attributes.

V

The sister narratives Yo-yo (Jójó 2011) and For Lísa (Fyrir Lísu 2012), as well as Sunshine Horse, are about tormented characters who were betrayed by their nearest and dearest when growing up. The subject matter is child sexual abuse and its impact on survivors’ lives and self-image. Yo-yo is the first of Steinunn’s novels to be entirely set outside Iceland. The story is set in Berlin and follows Martin Montag, an oncologist in his thirties. He seems to live a good and relatively orderly life; he is successful in his chosen profession, enjoys his food and drink, jogs around the city every day and loves his girlfriend, Petra, wholeheartedly.

One day, an older male patient comes to see Martin and his whole life is turned upside down. The man’s presence is uncomfortable and he seems familiar but Martin can’t immediately place him. On X-rays, the man’s tumor reminds Martin of “a tiny yo-yo. A red yo-yo. A bright red yo-yo.” In the wake of the visit, fractured memories of trauma, which the doctor has tried to silence, start surfacing. The fragments are isolated at first and only triggered by specific sensations but then slowly come together to form a whole – a memory of a painful event in childhood. Martin was eight years old and on his way home from school when he met the man in question in a public park. The man lured him into a garage by promising to give him a bright red yo-yo, and then raped him.

We learn that Martin told his parents about the crime as soon as he got home but in spite of the evidence – blood in his underwear and the red yo-yo – no one believed him. Because his parents failed him, he swears never to speak of his experience and shuts his family out. Because of this, he has not had a chance to properly process the past and face the difficult emotions that accompany sexual abuse. The narrative faithfully describes the pain, guilt and shame that survivors experience over rape and over other people’s reactions to it. It also shows how trauma can return to haunt survivors at any time, with flashbacks and intrusive thoughts. Memories of the trauma also regularly intrude into the narrative, accurately reflecting how traumatic memories behave.

The impact of the crime is also discernible in Martin’s adult life. He could not stand the thought of being around children in medical school and got special dispensation so he would not have to do a rotation in pediatrics like all students were obliged to. He is also determined not to have children as he is afraid of being unable to protect them from pedophiles. Most importantly, he is full of guilt and sees himself as less than a man, as is often repeated in the story. No one knows about his past and he has neither been honest with himself nor Petra. Martin narrates the story in the first person but the narrative approach reflects the fracture in in his psyche as he sometimes talks about himself in the third person: “It annoys me that I can’t place him. What has become of Martin Montag’s steel trap memory?”

The narrative has a doppelganger element as one of the few people with whom Martin has been able to form a real bond is his former patient, namesake and contemporary, Martin Martinetti. The friends are both opposites and parallels. Martin Martinetti is a French down-and-out who was repeatedly raped by his father as a child. The friends have both suffered from suicidal ideation as a result of their abuse but unlike the doctor, who reacted to his trauma by retreating into emotional coldness and work, the Frenchman turned to substance abuse and became homeless. Neither has been able to forgive their mothers and others who chose to lie to themselves and ignore the abuse. The friends are like two halves who form one whole; they find strength and understanding in each other.

Interwoven with Martin’s story is that of Lísa, the daughter of the man with the yo-yo-like tumor. Martin remembers meeting her in the hospital’s psychiatric ward when he was a medical student, when she claimed her father raped both her and her brother, who took his own life. Reading Lísa’s medical file, Martin sees how her credibility and the validity of her story have been systematically undermined and she has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder with delusions of sexual abuse. Among the things that count against her is her father being “a respected official”.

In the sequel, For Lísa, Martin seeks Lísa out, wanting to face up to the past and seek justice. While Yo-yo is an inward directed narrative which relates Martins mental anguish, For Lísa is an externally directed story in which the secret of the abuse is revealed. Both stories raise complicated questions about power and responsibility. How do pedophiles use their power to get what they want and what is the responsibility of those closest to both the children and the abusers? Is it possible that mothers are unaware of their spouses’ abuse of their children? And if they are aware, why do they most often side with the abuser?

Steinunn’s stories of Martin and Lísa were published when people were beginning to discuss the sexual abuse of women and children more openly than before, but nonetheless, they were and are a much-needed reminder of the impact of this abhorrent violence and of the importance of protecting and respecting children. Although Yo-yo, For Lísa and Sunshine Horse are about child neglect and the impact of serious trauma, Steinunn’s characteristic humor and irony shine through in all three texts. Comical descriptions, playful conversations, and colorful characters keep the stories from becoming purely tragic, unlike the misery porn which often appears in the media.

VI

The tone of the novel Women of Quality (Gæðakonur 2014) is lighter than that of the books about Martin and Lísa. The subject is love, but this book does not center on heterosexual love but rather love and eroticism between women. The main character is volcanologist María Hólm who is “[n]ot only charming and highly intelligent but also a world class scientist – a prodigy”. She is at a turning point in her life, divorced and grieving for lost love. In Paris, she meets the Italian Gemma, a curious character who has been following her. Gemma has strong ideals and envisions a new world order in which women are dominant. She holds men responsible for the woes of the world and refers to them as rapists and destroyers. She believes women are better off taking each other as lovers than being with men. Gemma is so convincing that María wonders for a while what it would be like to live with a woman but when push comes to shove it does not work out.

Women of Quality is also partly about the love that exists between friends and that is maybe the most real kind of love described in the book. Ragna, María’s friend, is always there when needed. María’s bond with the natural world is probably the most important relationship in her life and the story is partly an ode to Icelandic nature, which both gives and takes. María is strongly connected to the land through her work and it is even present in her name. The story refers to volcanic activity in Vatnajökull glacier, more specifically the Bárðarbunga volcano, on which María is an expert. It is an amusing coincidence (or a divination!) that the year Women of Quality was published, Bárðarbunga started to make itself felt in that world which we call the real one.

Women of Quality is a majestic work full of possibilities for interpretation. Although it deals with various philosophical questions, exuberance and dazzling irony characterize Steinunn’s text, which flows unstoppably like a stream of lava (to choose a simile in the spirit of the book).

VII

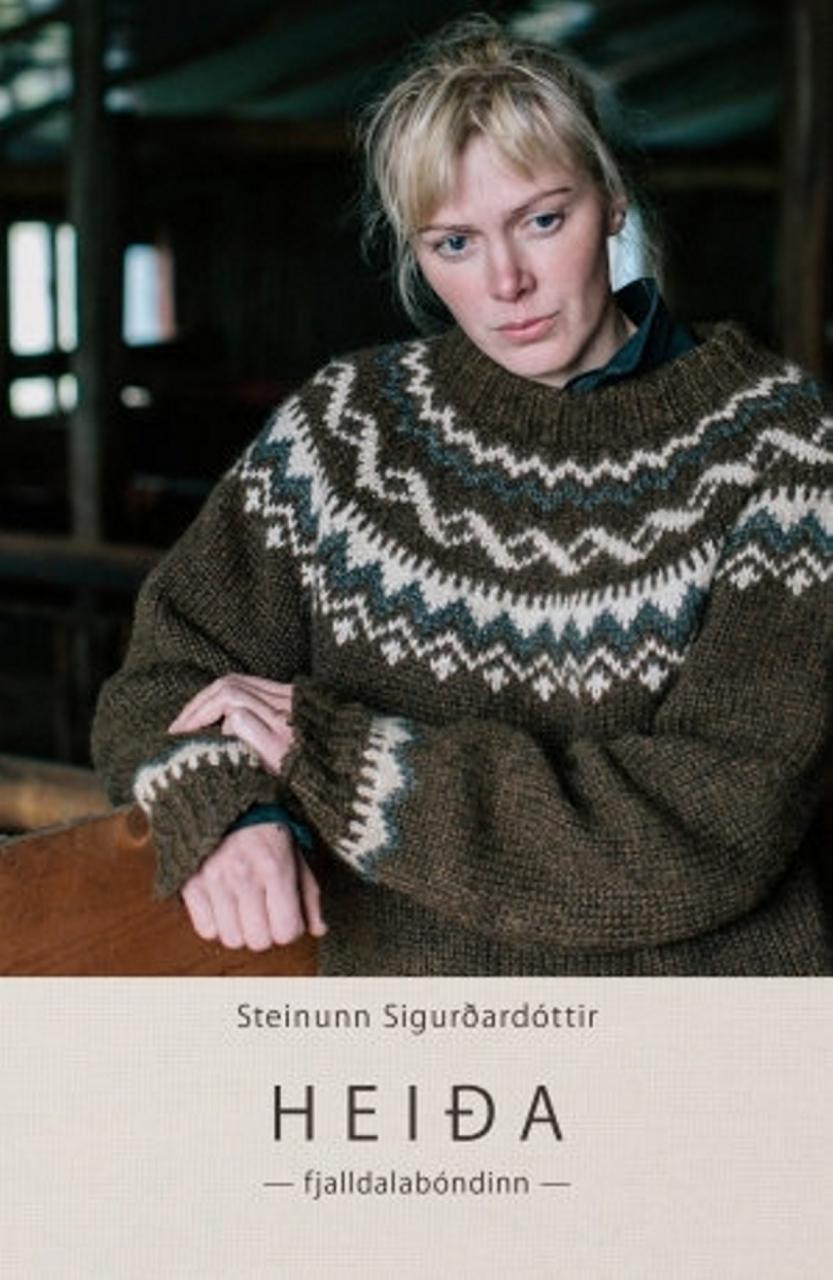

As already mentioned, nature is very important to Steinunn and she writes on it in her poetry, novels, and biographies. She often uses unexpected and novel images of nature to encourage reflection in the reader. Steinunn is a nature conservationist and her views on the subject are evident in her non-fiction book Heiða – A Shepherd at the Edge of the World (Heiða – fjallabóndinn 2016). In it, she describes how a major corporation wants to acquire a piece of land to use for a hydroelectric power plant and farmer Heiða Guðný Ásgeirsdóttir’s attempts to thwart them. When writing about Heiða, Steinunn plays interestingly with the biographical form, for example by emphasizing descriptive detail to give the reader an even better understanding of the conditions of life for a farmer in the mountains.

The collection of poems From Poetry You Were Taken (Af ljóði ertu komin) was published the same year as Heiða’s story. The title refers partially to Steinunn herself, who, as is well known, began her career as a poet and has always stayed loyal to the genre although several years sometimes pass between publications of her poetry. For example, readers had to wait nine years for From Poetry You Were Taken. The wait for her next collection of poems was shorter and To Poetry You Will Return (Að ljóði munt þú verða) came out in 2018. Both books are characterized by freshness despite their subject matter being familiar. Impermanence appears in various forms in both works and time, love, and death are central themes.

From Poetry You Were Taken is divided into several chapters containing, for example, maritime poems, poems on ultimate truths and on specific places in Reykjavík. As in Steinunn’s other poetry, death is interwoven with the concept of time and in the chapter “Across Everything and Nothing” she portrays the whole of life as preparation for the final moment with irony and originality. Rather than the purpose of life being recovery, as was memorably revealed in “A Few Bursts on Death and More”, every aspect of life has now become a bother. Steinunn’s poems remind readers that in the midst of living, people tend to forget to stop and enjoy the moment and so it is only in hindsight that moments become great and we finally realize their importance.

One chapter of the book is dedicated to friends who have passed away. However, the poet does not write about specific individuals, as is usual for traditional elegies, but about continuing friendship after death or, more specifically, how a person lives on in the thoughts of those left behind. The speaker gives an amusing and ironic description of the dead participating in daily life despite seldom having anything new to contribute. Despite the irony and humor so familiar to Steinunn’s readers, the tone of the work is somewhat darker and more sober than often before.

In the opening poem of To Poetry You Will Return, the speaker addresses the breeze – the artery of poetry? – and asks it to sing about the shade which follows the speaker and so to reveal who it is. The poet ranges widely in this excellent collection. It is divided into six chapters in which she writes about travel, poetesses, the sun and the human condition, to name few subjects. Time, love, and death also all appear, as is indicated by the opening poem. However, we do not tread familiar ground here but rather, the poetry is fresh and new. The poems are characterized by ambiguity, contrasts, strategic similes and striking repetitions, which increases their impact. Nature is given its due and although the sun is allowed to shine and we are repeatedly shown images of natural beauty, the reader is also thoroughly reminded of just how badly humanity has abused the Earth.

VIII

On her fiftieth writing anniversary, Steinunn published a collection of poems titled Dusk (Dimmumót 2019), a striking and powerful series of poems about Vatnajökull glacier. The book is both a majestic ode to the glacier and a lament for its destruction – writing about a world that was and a world that will be. In Steinunn’s poems, the glacier is no longer a symbol of eternity, as it was for example in the novel Heart Place (Hjartastaður), but now has become a symbol of transience. As the poet expresses so brilliantly, anthropogenic climate change has impacted the glacier, and it is slowly disappearing.

The term “dusk” means the beginning of darkness falling and so the book’s title reflects the shift climate change is causing in the world, evinced by deglaciation. When the white ice melts, the black rock is left bare, darkness succeeding light. For the first time in her career, Steinunn weaves her own life into her poetry. The reader follows the poet’s childhood and her introduction to the glacier and the natural world in the first part of the book, “Comes to Light”. The glacier is not eternal and the blame lies with humanity, which is well aware of the impact of the climate emergency but does nothing to combat it. Many of the poems in Dusk are full of grief over a world that is lost. It is especially poignant how Steinunn repeatedly pairs together the small and the large to demonstrate the impact of global warming on both individuals and the whole of humanity, on Vatnajökull glacier and the glaciers of the world.

Steinunn has often written poetry about man’s destruction of nature but she has seldom been as blunt or as scathing as in Dusk. Making no attempt to soften her tone, the poet underlines her opinion of human impact by referring to us as “matricides”, “destroyers with sledgehammers” and “the blood suckers”. After all, there is no reason to tread softly when the survival of nature and the whole world hangs in the balance; it is time for the neglect to end. The glacier is bleeding out and Steinunn writes about the terrifying impact of deglaciation on humanity and the whole biosphere. The future looks dark and it is not only humanity that suffers for its actions, as is made clear in Steinunn’s book; species go slowly extinct and “[t]he ocean acidifies and turns to plastic”.

With such rich emphasis on the impact of climate change on the whole world, the collection has the hallmarks of climate literature, a genre which has grown established over the last few years.

IX

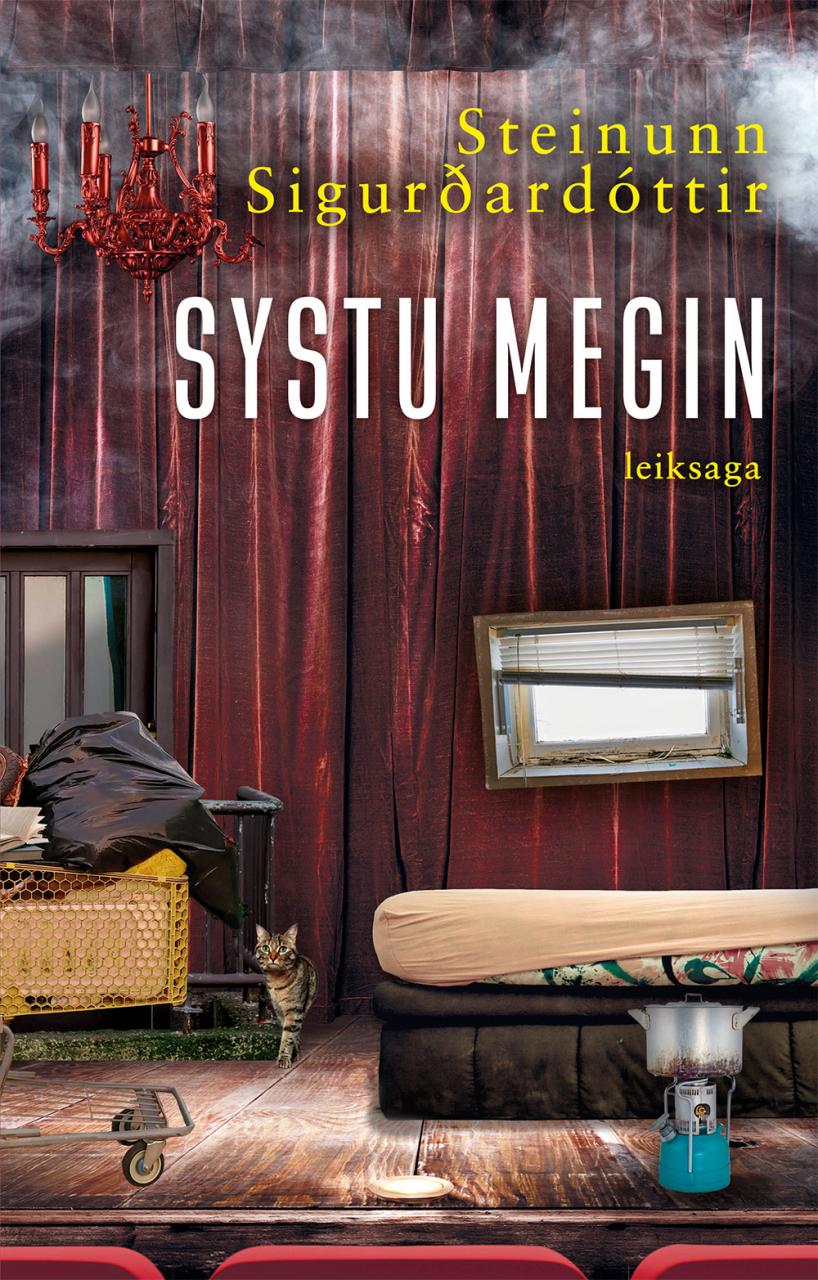

Steinunn’s latest book is the “playstory” Systu megin (2021), which could be translated either as Systa’s Side or Systa’s Might. The title of the book is ambiguous, referring both to the story being told from the point of view of the book’s main character, Systa, and to Systa’s strength. Systa is a destitute down-and-out whose life is shaped by poverty. She survives by collecting cans but there is strength in her resourcefulness. The story is set at Christmas, when poverty is most felt. The work emphasizes the contrast between rich and poor, miserliness and generosity, but avoids banalities in doing so.

The full title of the book is Systa’s Side – A Playstory and, as is implied by the subhead, it is a mix of two genres, a novel and a play, albeit in a very different way from The Glacier Theater. This unusual narrative approach is very effective in Systa’s Side and allows Steinunn both to give a marginalized woman a voice and a face and to give the reader insight into the experiences of impoverished people trying to survive under very difficult conditions. Systa’s inner voice is presented to the reader in short chapters of prose in which she describes her life and poverty in considerable detail – for example, her living conditions, diet, coffee consumption, hard work and chronic illness – as well as her childhood and her relationship with her late father and her miser mother. The descriptions are cutting but free of bitterness. The backbone and development of the story are then formed by conversations – or the lines of a play –, giving the reader better insight into Systa’s personality, her situation and the people around her. Although these narrative modes together form a pretty comprehensive picture of Systa there are plenty of blanks left for the reader to fill in. For example, we are never explicitly told which illness Systa suffers from or why she fell into poverty.

Steinunn addresses child neglect in Systa’s Side, much like in Sunshine Horse. Like Lilla and Mummi, Systa and her brother, Brósi, were ignored and neglected by their mother while growing up. Although the two stories have much the same subject matter, the treatment is very different. Systa and Brósi’s father was a sailor and when he was at home, he was a protector who cared for the children, made sure they got enough to eat, read them literature and got them Christmas presents. He died when Systa was fourteen years old and Brósi was twelve, which was a great loss to them as, unlike him, their mother was both stingy and terrifying. When the children were growing up, she resented every bite they ate despite having plenty of money and she now has tens of millions in the bank but does not have the decency to aid her impoverished daughter. It is tempting to read the mother’s stinginess as symbolic for the authority of a society which has adequate funds but chooses not to use them to aid those who need it most. The book is then a severe critique of Icelandic society, which allows poverty to continue even though everyone here should be able to have acceptable quality of life.

Systa’s Side is centered on the conditions of life for marginalized people and, apart from Systa herself, the reader is introduced to Lóló, an alcoholic homeless woman with one leg. Despite being homeless, she is really Systa’s only supporter. The story also addresses contemporary slavery and human trafficking. Although the subject matter is sobering, Steinunn prevents the narrative from becoming purely tragic with plenty of ironic descriptions and hilarious conversations and adds a spark to the text with countless original and clever neologisms, as she is wont to do.

X

“Literature can give meaning to silence and a voice to the voiceless,” said writer Elif Shafak. Her words apply to many of Steinunn’s works, which represent people who never could have told their stories without assistance. This is true, for example, of Systa the down-and-out, Lilla the neglected child and survivors Martin, Martin and Lísa, not to mention nature, which Steinunn has been advocating for her whole career. Steinunn is unflagging in demonstrating the diversity of human experience and the importance of nature conservation to her readers while systematically dissecting various societal ills. Steinunn’s treasury of stories and poems is large and precious. This article only mentions some highlights and there is plenty more to be enjoyed. Steinunn’s works are complex and demonstrate great inventiveness, a unique facility with the Icelandic language, fascinating narrative worlds and interesting characters. Although certain themes – time, love, death, obsession and nature, to name a few – resonate throughout Steinunn’s oeuvre, she constantly manages to surprise her readers with fresh approaches and unexpected points of view because she is unafraid to walk new paths and to take risks when it comes to subject matter and narrative mode.

Guðrún Steinþórsdóttir, 2021

Transl. Eva Dagbjört Óladóttir, 2022

Articles

General articles and criticism

Gert Kreutzer: “Jahre wie Pfeilschüsse ins Nichts: Zur Lyrik von Steinunn Sigurðardóttir.”

In Isländische und färöische Gegenwartsautoren.

Köln: Seltmann und Hein, 2002.

Lakis Proguidis: “Le roman du temps et de la poésie : entretien” (viðtal)

L'Atelier du roman. 1999, 17, p. 111-121

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir: “Oranges, mussels and monstrous flowers”

Klima/Climate: Nordic Poetry 1984-1994, København : Transit Production, 1994, p. 44-51.

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir: “Selvportretter i tiden”

Nordisk kvindelitteraturhistorie, vol., 4. København : Rosinante/Munksgaard, 1997.

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir: “Steinunn Sigurðardóttir.”

Icelandic Writers (Dictionary of Literary Biography). Ed. Patrick J. Stevens. Detroit: Gale, 2004. 322-27.

See also: Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature. University of Nebraska Press, 2007, 455-56, 489 and 543-44.

On individual works

Ástin fiskanna (The Love of the Fish)

Ástráður Eysteinsson: “Adskillelsens kunst/The Art of Separation”

Nordisk Literatur/Nordic Literature Magazine 1994, p. 66-7.

Byrman, Gunilla: “Steinunn Sigurðardóttir. Fiskarnas kärlek”

Gardar, 26, 1995, p. 35-36

Dimmumót (Dusk)

Lilja Schopka-Brasc: "Nachtdämmern"

Island : Zeitschrift der Deutsch-Isländischen Gesellschaft. 2022, 28 (2), p. 53-55

Góði elskhuginn (The Good Lover)

Vala Hafstað: “Unsatisfied love”

Iceland review 2017, 55 (2) p. 8

Hanami

Dagný Kristjánsdóttir: “Du er hvad du gør”/“You are what you do”

Nordisk Literatur/Nordic Literature Magazine 1998, p. 70-71.

Heiða: fjalldalabóndinn (Heiða: a shepherd at the edge of the world)

Elin Thordarson : “Heiða: a shepherd at the edge of the world”

The Icelandic connection. 2021, 72 (1) p. 44-45

Hjartastaður (Place of the Heart)

Ástráður Eysteinsson: “Fra narko til natur/From Narcotics to Nature”

Nordisk Literatur/Nordic Literature Magazine 1997, p. 19.

Radka Lemmen. “Auf dem Weg zum Herzort : Überlegungen zum gleichnamigen Roman von Steinunn Sigurðardóttir”

Island : deutsch-isländisches Jahrbuch. 2001, 7 (2), p. 24-29

Síðasta orðið (The Last Word)

Anna Orrling Welander: “Steinunn Sigurðardóttir: Sista ordet”

Gardar, 25, 1994, p. 27-28

Tímaþjófurinni (The Thief of Time)

Coletta Bürling: “Steinunn Sigurðardóttir. Der Zeitdieb”

Island : deutsch-isländisches Jahrbuch. 1996, 2 (1), p. 39-44

Robert Zola Christensen : “Steinunn Sigurðardóttir. Tidstjuven”

Gardar. 24, 1993, p. 47-48

From reviews

Ástráður Eysteinsson: “The art of separation”

The Love of the Fish

Nordic Literature Magazine 1994

Like her Tímaþjófurinn (Thief of Time,1986), this work is a study of the irony inherent in this mode of adress: My love. The word refers to the person loved, but also to the feelings of the speaker, and thus to the image one forms of the loved other – an image that may turn into an icon of love as such. We shape other people, especially those we love, into effigies, which then serve as our guides to the world. [...]

[The narrator’s] world is not upset by a classical this book is probably best called a novella, with various links to both the novel and poetry, as well as painting and music. It is a complex, intricately arranged, although eminently readable and sensual work of art, one that crystalizes the effect of love: the discovery of a new world.

(66-7)

Ástráður Eysteinsson: “From Narcotics to Nature”

Heart Place

Nordic Literature Magazine 1997

The novel [Heart Place] involves a remarkable rediscovery of nature in Iceland. Harpa Eir [the narrator] may be a poet who only writes for herself – and strewn through the novel are humorous titles and phrases she composes for her own biopgraphy, if it were to be written – but through this character, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir has captured one of the most compelling visions of Icelandic natural vistas in recent literature: romantic, yet not sentimental, sometimes ironic, yet deeply sincere. These vistas, and the fog that envelopes them on the second day of the journey, create a luscious and sensual context for the dialogues and ruminations that run so buoyantly through the novel, and yet with a strong emotional and aesthetic resonance. Steinunn Sigurðardóttir has proven once again that it is possible to write fiction that is charged with both poetry and narrative drive.

(19)

Awards

2023 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Ból (Lavaland)

2017 - The Guðmundur Böðvarsson Poetry Prize

2017 - Fjöruverðlaunin – The Women’s Literature Prize: Heiða – fjallabóndinn (Heida – A Shepherd at the Edge of the World)

2016 – The Booksellers‘ Prize: Heiða – fjallabóndinn (Heida – A Shepherd at the Edge of the World)

2014 – The Jónas Hallgrímsson Prize

2011 - The Booksellers‘ Prize: Jójó (Yo-yo)

1995 – VISA Cultural Prize

1995 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Hjartastaður (Place of the Heart)

1990 – The Icelandic Broadcasting Service Writer’s Prize

Nominations

2019 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Dimmumót (Dusk)

2016 – The DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Af ljóði ertu komin (From Poetry You Came)

2012 - Fjöruverðlaunin – The Women’s Literature Prize: Jójó (Yo-yo)

2011 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Jójó (Yo-yo)

2009 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Góði elskhuginn (The Good Lover)

2005 – The DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Sólskinshestur (Sunshinehorse)

2005 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Sólskinshestur (Sunshinehorse)

1999 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Hugástir (Loves of the Mind)

1997 – The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize: Hjartastaður (Heart Place)

1996 – The Aristeion Award: Hjartastaður (Heart Place)

1994 – DV Cultural Prize: Ástin fiskanna (Love of the Fish)

1990 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Síðasta orðið (The Last Word)

1988 – The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize: Tímaþjófurinn (Thief of Time)

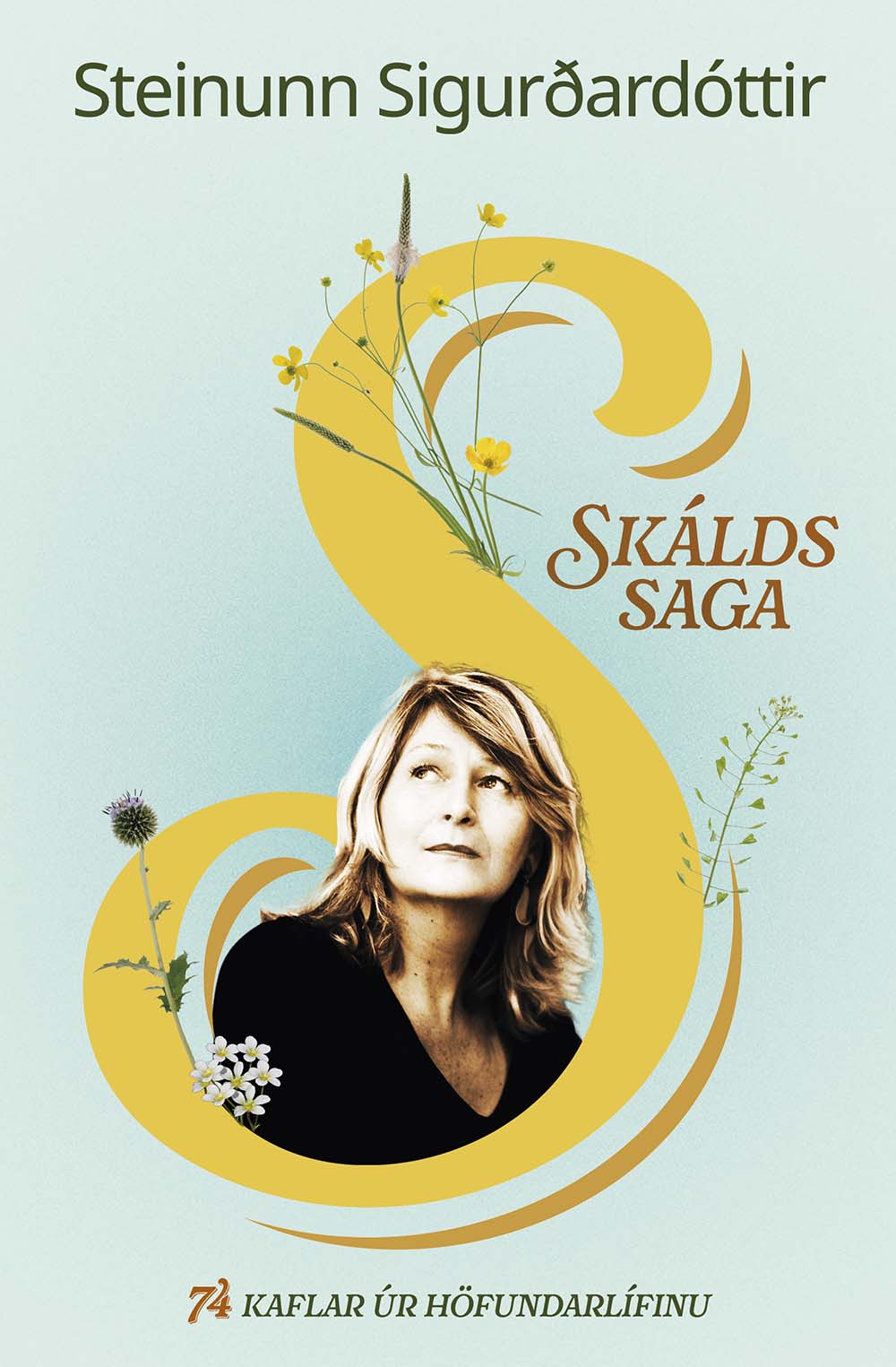

Skálds saga (Writing Life: 74 Steps on the Writer’s Path)

Read moreVerðlaunahöfundurinn Steinunn Sigurðardóttir hefur á löngum ferli samið fjölda skáldsagna, ort ófá ljóð og skrifað vinsælar sannsögur, en hér er hún á nýjum slóðum og segir frá sjálfri sér, viðhorfum sínum, aðferðum og aðstöðu við skriftir.

Ból (Lavaland)

Read moreOg ef ég hefði bara fengið að vera kall þá hefði mér verið hlíft við ástinni á Hansa mínum - ofurást konu á manninum - sem er örugglega enn djöfullegri en ofurást manns á konu. Samanber mömmu. Mömmu mína.

Systu megin (Sis's Way - A Play in Prose)

Read moreSis‘s Way is a sharp and unique story about outsiders being given both a voice and a face.

Heiða : a shepherd at the edge of the world

Read more

Dimmumót (Dusk)

Read moreFrom the bright perspective of the child delighted by the white of a timeless mountain we are taken to the uncertainties and transitions of our time.

Heiða : fjallabóndinn (Heiða : a Shepherd at the Edge of the World)

Read more

The Good Lover

Read more