Bio

Ævar Örn Jósepsson was born in Hafnarfjörður on August 25, 1963. He is the youngest of four siblings. He lived in the Reykjavík suburb of Garðabær for the first two years of his life (and claims to have escaped from there without permanent harm), then in Hafnarfjörður, but moved to the countryside, close to the town of Akranes, when he was 16 (he was bribed with a dog). He finished higschool in Akranes in 1983, having been an exchange student in Belgium from 1981-1982. Ævar Örn studied journalism, political science and philosophy at the University of Sterling in Scotland from 1986-1987, and graduated as Magister Artium of philosophy and English literature from Albert-Ludwigs Universität in Freiburg, Germany in 1994.

Ævar Örn has done various jobs through the years. He worked on fishing boats, and as a worker here and there in the summers as a student. He was a bank employee from 1984-1986, did programs for television in 1986 and on radio in 1987 and 1988, as well as writing about popular music for the newspaper Þjóðviljinn. Ævar has worked as a journalist on and off since 1994, for instance for Morgunblaðið newspaper, the webjournal visir.is, Ský magazine and other journals. He has been a freelance translator, and translated various articles, reports, self-help books and other material. Ævar Örn has worked for RÚV radio (The National Broadcasting Company) since 1995, both freelance and steady, mostly doing daily magazine programs.

Ævar Örn has sent forward five crime novels, all involving the same team of police investigators. The first one was Skítadjobb in 2002 (A Shitty Job), followed by Svartir englar in 2003 (Rock Bottom), Blóðberg (A Cold Place to Die) in 2005, Sá yðar sem syndlaus er (Without Sin) 2006 and most recently Land tækifæranna (Land of Opportunities) from 2008. His short story, “Línudans” was published in the German collection Spannendsten Weihnachtgeschichten aus Skandinavien, as “Sorge dich nicht, sterbe” in 2004. Svartir englar and Blóðberg have also been published in translations.

Ævar Örn Jósepsson lives in Mosfellsbær, close to the city of Reykjavík. He is married to Sigrún Guðmundsdóttir who is a biologist, and they have two daughters.

Publisher: Uppheimar.

Author photo: Friðþjófur Helgason.

About the Author

Stumbling Over a Clue: The Crime Fiction of Ævar Örn Jósepsson

It is a well known fact within women’s literature that many women writers start their career late in their lives, often around middle age. Male authors, on the other hand, usually begin writing at a young age, bathing in the glamorous aura of the young genius. This ‘rule’ was strikingly broken, as so many other rules of Icelandic literature when crime fiction suddenly became a common sight in the novel-scape. Arnaldur Indriðason (1961) had of course written a lot as a journalist of many years when he wrote his first crime novel in 1997 and the same goes for Árni Þórarinsson (1950), who had also written a biography (1994), before publishing his first crime novel in 1998. Despite this, neither could be called an author in the traditional meaning of the word. Ævar Örn Jósepsson (1963) joined this group of ‘middle-aged’ crime writers in 2002, when he, barely forty years old, launched his career as a crime author with Skítadjobb (A Shitty Job). Actually he started with a double slam, in addition to the crime novel he also published Taxi, a book of interviews with taxi drivers working in Reykjavík.

While it is not my intent to recreate the story of the rise of the crime novel in Iceland during the past decade or so as a whodunit, I find it prudent to acknowledge and ponder upon the role of the association The Crime Writers of Iceland in the growing popularity and respect that crime fiction has acquired in these years since Arnaldur published Synir Duftsins (Sons of Earth) – and actually also Stella Blómkvist (a pseudonym for an unknown author), she also debuted in 1997.

The society of The Crime Writers of Iceland was formally founded in 1999. Members are however not only writers of crime fiction, but people who have worked to further the progress of crime fiction – writers, critics and others who promote this genre in one way or another. The association right away applied for membership of the Crime Writers of Scandinavia (CWZ) or SKS (Skandinaviska Kriminalsällskapet), and thus assured Icelandic authors the right to participate in the competition for the ‘Glass-Key’, the annual prize for the best Nordic crime novel. The rest is history, Arnaldur grabbed the key blithely from the unsuspecting Scandinavians two years in a row, 2002 and 2003, became a bestseller locally and abroad and suddenly home-grown crime fiction was hot in Iceland. Apart from these victories, the Icelandic offer has become the runner up for the prize, for example when Ævar Örn’s own Svartir englar (Rock Bottom) was a contender in 2005. I do not intend in any way to reduce or belittle Arnaldur’s talent when saying that the foundation and work of The Crime Writers of Iceland has without doubt played a role in promoting and supporting Icelandic crime fiction and writings about crime fiction, and thus contributed considerably to the favourable outcome of the case.

Ævar Örn Jósepsson was working as a host of a popular radio-programme at the National Broadcasting Service when he joined the association as a particular crime fiction enthusiast and supporter. He soon took an active part in the work of the association, among other things sitting on the jury that nominated the Icelandic contender for the Glass-key, as well as choosing the best Nordic crime novel. But suddenly Ævar Örn was not acceptable for such jobs; he was now on the other side of the table, a crime writer in his own right. This did not prevent his further advancement within the world of crime, in the 2004 SKS/CWS annual general meeting he was voted the president of SKS, and re-elected again in 2005 and 2006.

A Shitty Job Ævar Örn treads a path between the traditional and untraditional in his stories. It can be said that his approach to the form is rather traditional, his four novels to date are detective stories with a two male team in the main roles, and this odd couple is then a part of a larger team within the department of criminal investigation. On the other hand his take on the classic police couple is rather startling. Stefán, the boss, is the representative of the old hand, a type that tends to be bitter and resentful, usually divorced or having serious problems in his love life. Ævar’s take is however to portray him as a very gentle guy, calm and warm, and moreover, happily married to the same woman for more than three decades. The representative of the young and upcoming, traditionally an ambitious and well educated yuppie-like character in today’s crime-fiction, is no such thing in Ævar’s novels. To the contrary, the newcomer, Árni is very much a blunderer and something of a loser in Ævar’s debut novel, Skítadjobb. He is a thirty-something, wishy-washy guy, who did not even finish the police-academy and seems to have wound up in the detective force by a complete coincidence, after having tried out various educations and jobs. It is actually almost a kind of side plot within the story to find out how he suddenly and surprisingly has landed this much wanted position within the police force, and in addition to this he has to try and find out who he is, what he wants and generally what he is doing here!

The story starts when Stefán and Árni are being called out on what seems to be a suicide, a body of a man lies on a pavement outside the tall apartment building where he lives. Even though the matter seems clear, Árni blurts out that he does not believe that this is a suicide, and despite the younger man’s lack of experience Stefán takes his words seriously and the matter is looked into more closely. A further investigation reveals a rather shadowy side to the victim, who in the beginning seemed to be a reproachless man.

What makes the story so rememberable and such a joy to read is largely the relationship between the two completely different men, and descriptions of how they react to each other and slowly learn each other’s ways. There are some hilarious scenes, such as when Árni shows up at work, heavily hung over, and is rather tiredly scolded by Stefán, while shown a kindly and almost fatherly understanding by him at the same time. In addition to this, there is the relationship that Árni has with his former about-to-be father-in-law, the medical examiner Geir, a friendship that contains the solution to at least one piece of the puzzle.

Rock Bottom It is considered a trend among crime writers to provide their readers with a new book every year, at least if they intend to last. Ævar Örn started immediately on this road and Skítadjobb was followed by Svartir englar (Rock Bottom, literally: black angels) in 2003. Again we meet with the same cosy team, the by now good buddies Stefán and Árni, but now we also get to know better some other members of the detective force, such as Guðni, a tough and rough cop of the old school, Friðrik, who is young, educated and ambitious (they of course are perfect prototypes for the traditional cop-team, only here in a supporting-role), and Katrín, the only women in the group. She is the ‘token’ woman, and is about to become a substitute boss while the chief, Stefán, goes on a holiday. Those three are all a welcome addition to the story, adding further flavours to the clever characterization already so in evidence in Skítadjobb. And the fact that they are a tad stereotypical is actually just fine!

In the beginning of the novel this dashing team is searching for a lost woman, Birgitta.[1] Much emphasis is placed on finding her, even though she has only been missing for 24 hours or less, but the detectives are not told why this is so important. Thus, in the first part of the story the team are interviewing people and investigating Birgitta’s disappearance without really knowing what they are supposed to be asking and why they are doing it. This is an effective trick and involves the reader successfully. Alongside this Árni keeps a one (sleepy) eye on other, minor cases, such as trying to track down stolen computers (using the alias Erlendur[2]) and wonders why a well known bum in Hlemmur-bus-stop is terrified. In addition to this there is a bitter struggle within the police force, between Guðni and Katrín, Guðni claiming that it is a humiliation for him to be subordinated by a younger person and in particular a younger woman. This calls for discussions on the position of women with in the police, a subject that is very popular these days, for a good reason, as it is both interesting and important. Ævar manages to handle this well without stumbling over to many gender-clichés. The discussion about gender is then furthermore enhanced in Árni’s complexes over his sexual fantasies, but he considers himself a feminist and is horribly ashamed when he cannot help fantasising about the women around him.

Then matters start to become more entangled, a heavy conspiracy-theory appears and the pace becomes faster. Still the pace is generally never all that fast, Ævar does not write so-called fast-paced novels, his style is more contemplative and focused on characterization and staging. The plot of the first book focused on a rather ‘traditional’ crimes, connected to drugs and such like underground-operations, while Svartir englar concerns itself with a different kind of social problem; the electronic surveillance of the individual by the authorities. Following upon the terrorist attack on New York in 2001 some countries have passed new laws that make it easier for the state to keep a much closer eye on their citizens, a surveillance that is nothing short of an intrusion into personal privacy. Examples of this include laws that authorize the police to gather, without sufficient evidence, information into the databanks of libraries, and thus map reading habits, computer usage and other private occupations of individuals and groups. And Birgitta is a system analyst who has been working on secret projects...

A Cold Place to Die The area of Kárahnjúkar, a highly controversial power-plant is being built that has sparked a serious dispute about environmental issues and the status and impact of foreign workers in Iceland. These are the main subjects of Ævar Örn’s third crime novel, Blóðberg (A Cold Place to Die, literally: blood-rock/timian), published in 2005. Way up in the uninhabited Icelandic highlands, where a huge dam is being built, and a landslide in a rocky canyon kills six people. In the wake of the tragedy the man in charge of security matters at the building site appears to commit suicide. Our people are sent all this way to the east of the country – a day after Árni throws a party for his colleagues with his new girlfriend. He met her during the investigation in Svartir englar, but until then his love-affairs had been rather tricky. It soon appears that the detective does not share the same views on environmental issues and as before the main dispute is between Guðni and Katrín. Friðrik, on the other hand, has now become a member of another police force, more concerned with security issues, after dramatic events relating to the investigation of Birgitta’s disappearance in the previous novel. Árni keeps on stumbling upon solutions, even though he fails to bring proper winter-clothing to the mountains, but the Kárahnjúkar-area in winter is described as particularly inhospitable.

As before the main value of the story is in how the author creates a convincing stage for his characters and plot, and it is quite impressive how the unsuspecting reader suddenly finds him/herself exposed to cold and bitter wind in the rugged landscape of the power plant/dam construction site, sunk ankle deep in snow and sand and stumbling though rocky terrain. A considerable emphasis is placed on describing the everyday life of the workers, giving a particular attention to the culinary side; the diet is, to say the least, unhealthy – that is, traditional Icelandic. This culinary theme is actually a lively thread through much of Ævar’s writings, already in the first book it comes to light that Árni is a good cook, and that his mental state – or, more precisely, his mental confusion – can be gauged through his eclectic shopping for food. Early in Blóðberg the reader is treated to expansive and appetizing descriptions of how a leg of lamb is cooked in a LOT of garlic, as well as being flambéed in whisky. These descriptions offer a striking contrast to the portrayal of the food at Kárahnjúkar.

The case seems to be complicated by many issues, such as those connected to the security of the area. There is a question as to the landslide itself, was it a natural landslide, an unfortunate accident or was it set off by a bomb? The only survivor, Jorge from Portugal, was overheard talking about an explosion in his delirium. There are rumours of terrorism. Also it appears that there are those with a good reason not to grieve too much over at least four of the dead, and thus the detective team have many avenues to explore. Finally the apparent suicide of the security officer raises more than a few questions, which should not come as a surprise, as readers have already gleaned that suicides in the works of Ævar Örn may not be as straightforward as they appear to be. And then there are various other dirty things going on at the Kárahnjúkar-site...

Blóðberg is an excellent example of how what some regard as a ‘lowly’ genre of literature can throw a new and fresh light onto a very worn-out political issue. The power plant at Kárahnjúkar has been a highly contested matter in Icelandic society for the past years, where any rational discussion has drowned in heated arguments between the extremes of suited industrialist right-wing politicians, and dread-locked over-romantic left-wing environmentalists, dressed in Icelandic woollen jumpers, skirts and hats. Such a shouting-match does nothing to engage the general citizen and thus a very important political and environmental matter has for many become an abstracted irritation. With Blóðberg however, Ævar Örn brings Kárahnjúkar home. Not with some highly handed environmental power plant polemics, but simply by providing an insight into the construction site at Kárahnjúkar as a work place, located in a cold and hostile part of Iceland (one of legion), where people of many varied nations have to live and work. Apart from an emphasis on depicting the place itself in vivid terms, the daily life of the workers is given some attention, ranging from their accommodation to language problems.

Both sides of the environmental/industrial debate are given space in the book, each with a representative, but in addition to this, the general citizen, the one in-between who is neither a nature’s child nor a suited capitalist, is also given a spokesman, in the familiar figure of Árni, who is so unfamiliar with his own country-side that he fails to dress properly for the cold and hostile landscape that he has to work in. The landscape itself plays the main role in the novel, and the reader cannot help suddenly finding herself in the midst of this whirlpool of people, debates, and, above all, cold. A Portuguese worker welcomes the police-team to the site, saying: “Welcome to Alcatraz”, and Árni cannot help feeling that the description is apt:

Wherever there wasn’t snow there was rock, junk or sheer, black cliff. And the dirty brown stream of water cascading far below, in the middle of the gorge. On the way from the bride to the camp they passed some huge, yellow, mud-covered trucks crawling down the slopes, they drove past a closed petrol-station, gigantic steely barracks and countless containers, rusty oil-barrels and broken upended sewage-pipes, carts and heavy machinery of all sorts and sizes scattered about. All this was more r less covered in snow and so was the low-rise cluster of buildings that they passed by soon after. It looked bleak and not particularly inviting in the gray, dim light, like huddling horses or a remote farmhouse in long forgotten tales of wayward travellers in the wintry highlands. Despite friendly lights in the windows and a complete lack of fences, to Árni it all appeared just as hostile as did the thought of the infamous prison-rock, and he couldn’t help but think that the term Gulag would be an even more fitting description of this place. (138-139)

Descriptions like these also offer a nuance on the pride Icelanders take in their rugged and cold country, and a certain national pride surfaces when this hostile side is so emphatically shown, after all we are continually being told that this is what makes it so sublime.

Without Sin Ævar Örn’s fourth crime story, Sá yðar sem syndlaus er (Without Sin), published in 2006, is not as highly politically charged as Blóðberg. Still, there are important issues here, one is the rise of religious sects, and another is the growing indifference to our fellow citizens. A middle aged, divorced alcoholic is found dead, distressingly long after he is killed. He lived in an apartment building, was a member of a tightly knit religious sect, The Holy Truth, and had two children, and thus it is almost inconceivable that nobody noticed – or reacted to – his total lack of communication for such a long time. Still, it happened. Of course there are partly criminal reasons for this, but the issue is still there. Our detective team are now in a bit of a transitional stage; Árni is on a summer-holyday in Crete and only appears in the middle of the investigation, having been called home due to Guðni’s suffering a heart attack after being run down by a suspect. Before long it comes to light that the good preacher, the leader of The Holy Truth, is not quite as holy as he appears to be and the same goes for his brother, who runs an evangelic television-station. The family of the murdered man also seems slightly dubious and in addition to this a known petty-criminal is the dead man’s next door neighbour. This good neighbour seems to have some connection to a well known crime-lord, who in turn, seems to have some kind of link to the preacher.

Árni is not so much the main character here as he is in the other books which means that mainly Kristín but also Guðni get more space. Also there are changes within the police-department, people are moving around and upwards, creating some anxiety – and hope.

While religious conflicts are not at the centre of the novel, the theme of the religious sect The Holy Truth, and in particular the preaching of its leader, condemning heathen terrorists, call for speculations on the role of religion in contemporary society. Now, in the early twenty-first century we are faced with increased religious austerity, where social values are being replaced by stern religious dogmas, inciting lack of tolerance for other cultures. The Holy Truth turns out to be not as full of compassion for its fellow beings, even though they are members, as it claims to be, and thus it is indicated that such Christian righteousness is really not all that right.

Ævar Örn is a crime writer, and thus his novels are about crimes, murders, drugs and the darker sides of life in general. Despite this, however, they are not completely bleak. The lightness and humour inherent in his style also appears in the detective team, peopled by rather strange characters which at first seem totally at odds but can be very united when called for. Árni, the main character in (most of) the books, is a complete scatterbrain, but at the same time very sympathetic, and thus very easy for the reader to identify with. But, as we all know, according to a literary theory (which Árni rejected, among other things he tried educating himself in literature but gave up on it) a good crime novel must always have at least one character for the reader to identify with. This representative of the reader must not be too clever because the reader must also be able to find herself a bit more ‘in the know’ than the character. Of course crime writers have played at tricking unsuspecting readers by messing with this agent for identification, and Ævar is perhaps a little guilty of this – but, this does not change the fact that Árni plays his role well, both within the police-force and the stories.

Like all good crime writers Ævar Örn uses the form to tackle various social issues and conflicts, reminding the reader that while daily life trundles on, more or less without much incident, bad things are always lurking in the shadows. A story like Blóðberg furthermore reminds us that the narrative form of the (crime) novel is not necessarily just entertainment. Novels contain information and are an important tool for us to understand and analyse people and places and hot topics. The novel gives form to ideas, providing them with outlines and a frame, and though narratives we can experience and connect to people, places and events, thus making sense of the various sides of issues and debates.

© Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir 2006

[1] Birgitta is the name of the best known woman writer of suspence stories in Iceland.

[2] Erlendur is the name of the main character in Arnaldur Indriðason’s crime novels.

Awards

2009 - The Drop of Blood, the Icelandic Crime Writers’ Award: Land tækifæranna (Land of Opportunity)

Nominations

2010 - The Glass Key: Land tækifæranna

2007 - The Drop of Blood, the Icelandic Crime Writers’ Award: Sá yðar sem syndlaus er (Without Sin)

2007 - The Glass Key: Blóðberg (A Cold Place to Die)

2005 - The Glass Key: Svartir englar (Rock Bottom)

Leðurblakan (Flaggermusmannen)

Read moreWer ohne sünde ist

Read more

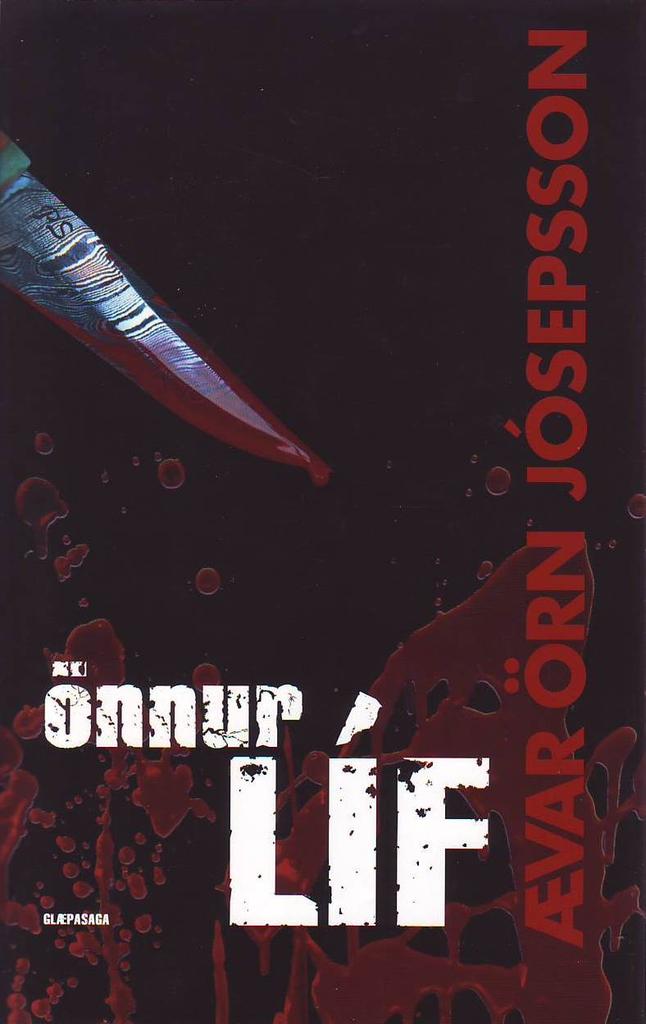

Other Lives

Read more

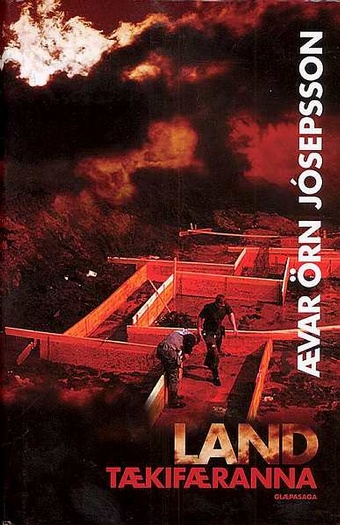

Land tækifæranna (The Land of Opportunity)

Read more

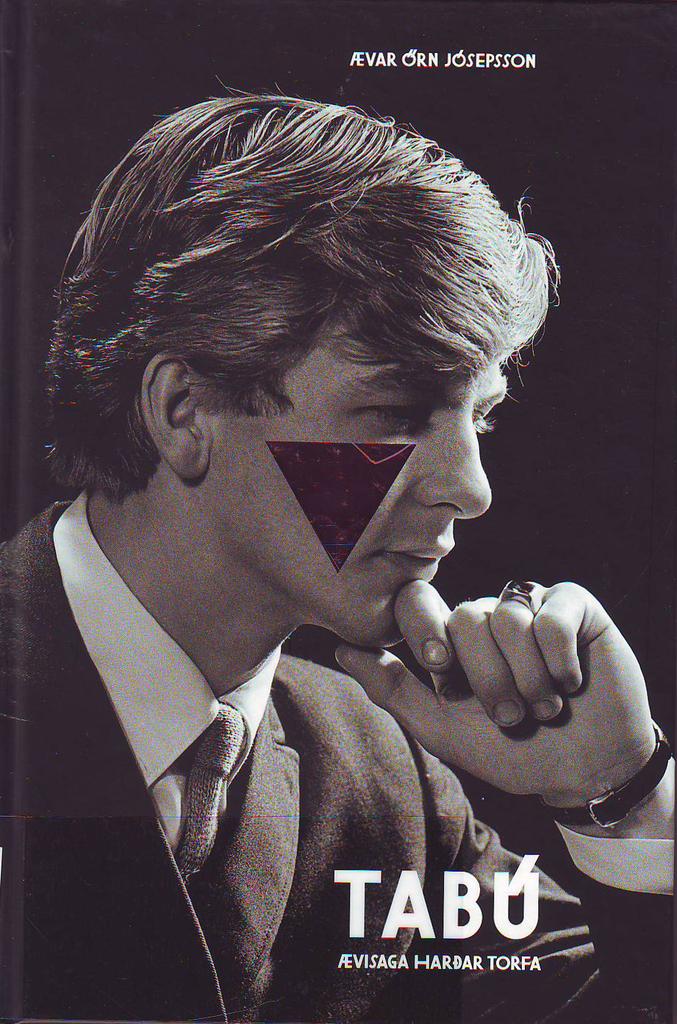

Tabú: Hörður Torfason - ævisaga (Taboo: A Biography of Hörður Torfason)

Read more

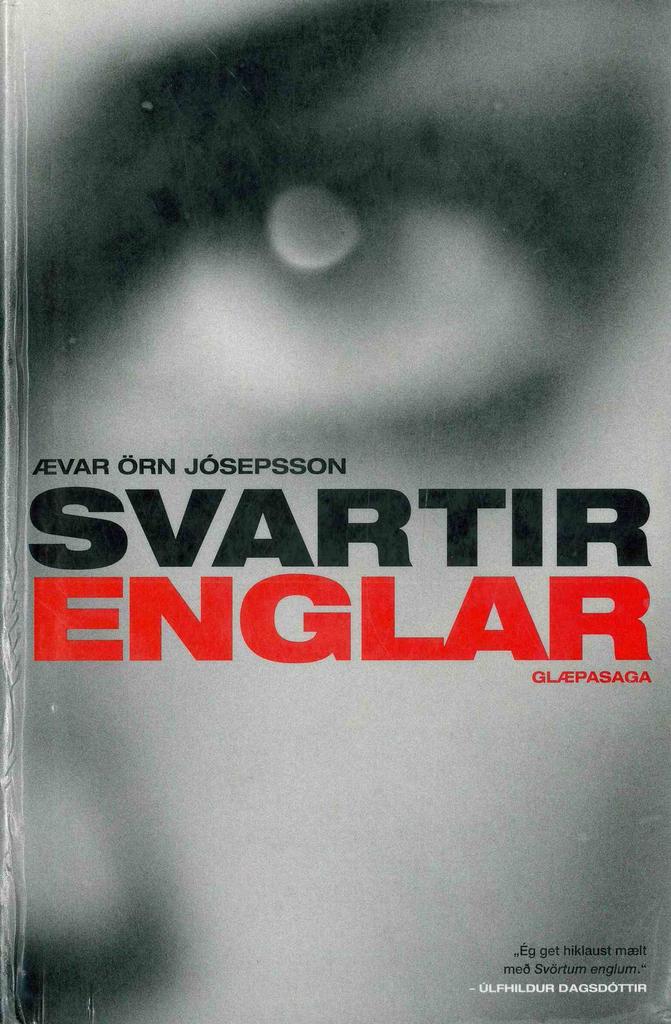

Svartir englar (Black Angels)

Read more

Sá yðar sem syndlaus er (You the one who is sinless)

Read more

Blodbjerget

Read more

Dunkle Seelen

Read more