Bio

Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir was born in Reykjavík on the 18th of March, 1938. After highschool she went to Catalonia to study literature and philosophy. She finished Lic. En fil. Y en letras-exam from the University of Barcelona in 1965 and a Dr. Phil-exam from the University Autónoma de Barcelona in 1970. She worked on her Doktoral thesis at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland from 1966-70.

Álfrún was an Assistant Professor in Literature at the University of Iceland from 1971-77. She was Associate Professor in the same field from 1977-87 and was a Professor from 1988 until she retired in 2006. In autumn 2002 she sat as Head of Department at the Liturature- and Linguistics Department at the Philosophy division.

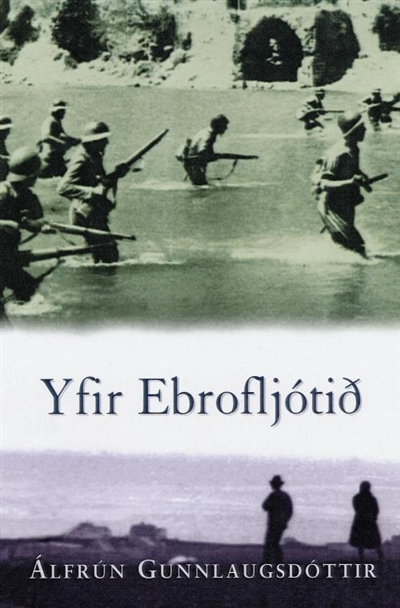

Álfrún published eight books of fiction, all to acclaim. She received the DV Literature Prize in 1985 for her second book, the novel Þel. Three of her novels have been nominated to the Nordic Council's Literature Prize, first Hringsól in 1991, then Hvatt að rúnum in 1995 and Yfir Ebrofljótið 2003. Yfir Ebrofljótið (Crossing the River Ebro) was also nominated to the Icelandic Literature Prize in 2001, and so was her novel Rán in 2008. Álfrún translated books from Spanish and wrote articles for academic journals.

In 2010 Álfrún was made honorary professor of the Icelandic and Cultural Division of the University of Iceland. In 2018 she was awarded The Knight's Cross of the Icelandic Order of the Falcon, for her contribution to Icelandic literature and university level education in the field of literature.

Álfrún died September 15th 2021.

Author photo: Einar Falur Ingólfsson.

From the Author

From Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir

The joy of creativity is in our blood. It can be seen all around us, as it touches upon most of human activity. It is a mixture of play and solemnity. For most people this mixture does not last all their lives; they do not seem to realise that these things are the two sides of the same coin. They allow the play to peter out.

Childhood games are a serious matter.

As a child I not only talked to my dolls, I filled the world with invisible people and talked aloud to them and on their behalf. I did not know anyone was listening until I started to meet the questioning looks from the grown-ups, sometimes the looks were quizzical and even piercing. Then I understood that it was not proper to talk to the invisible people in the presence of others. I felt a bit ashamed, maybe a bit hurt and fell silent. But I kept the dialogue going in my head. I was starting to suspect, although I could not put it into words, that one’s mind is one’s own.

Later I discovered that this point is not as straight forward as I had thought.

Even if creativity dwells within us, it does not always get to flourish. Not only does it need to be tended, it might also be necessary to fight for it and not let oneself be silenced.

I am not saying that in childhood one finds the reason for creativity and writing. I am merely pointing out the obvious fact that the joy of creativity is human. It would be pointless for an artist to create if others were not prepared to receive his work and thus take part in creating it with him.

In these relative times we live in, it would not be prudent to look for common characteristics among authors and a communal reason for writing. It is better to assume that the reasons are as many as the authors are, and that each author has more than one reason. This has never been fully looked into. But if truth be told I have a limited interest in the reasons why I write. Although I would like to point out that it is not because I believe the act itself to be shrouded in some mystery.

The so-called Western world has for a few centuries held on to the “obsession” for finding out the reason for most things. There is no effect without cause, as Pangloss maintains in Voltaire’s story Candide, and proclaims that the nose was created with the sole purpose of holding up spectacles. Although no one doubts the scientific value of looking for reasons, it is unnecessary to do much digging around if such digging is heading for trouble. For this reason the question why I write will be left unanswered. On the other hand, I have written enough stories to notice certain repetitions connected with the act of writing, something I should probably look out for since I notice them. I have for instance noticed my lack of enthusiasm for razor-sharp ideas when they concern myself. Upon closer inspection they are rarely strong enough to withstand scrutiny. An idea is supposed to be able to stand on its own and in order for it to be thus, work must be done on it and material spun from it. When I see a spark flying I blink my eyes just in case. I am also suspicious of the unstoppable flow. The pen flies across the paper (I do not use a computer until I reach the latter stages), the hand is in the service of the mind, but no matter how well it works only a fraction turns out to be of any use, a few spurts. This is where patience comes into play. I do not, however, believe that I sit with a censor beside me.

Unrestricted flow does probably not exist.

All things being equal it seems that I choose to write about things I am not keen on or am not content with, almost in spite of myself. Thus a conflict is created, which I use to try to sharpen the material and my hold on it. The plot does not come first as would be expected, but a character or characters and it takes a while to get to make their acquaintance. The introductions are like in real life, happy ones or not so pleasant ones, but the worst are the bullies who try to force their way into the story. Although I have not yet had reason to install security guards at the door.

Many have pointed out the fact that writing a novel is first and foremost work and that imagination has only a little part in it. I am not sure I agree with that. You need imagination to create a world. A world held up by words.

And what about the joy that comes with writing and has the face of Janus?

Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir, 2002.

Translated by Dagur Gunnarsson

About the Author

“Now you are telling stories”: memory, time and narrative in the fiction of Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir

I

“Bogga knew this by heart, still the story kept changing. New accounts kept being added, overthrowing earlier explanations. Almost impossible to figure out what was true or what was a lie. Or was it all just an illusion? When Daníel had become ill, sitting in a corner chair in the living room, she tried to ask, seeking fragments which she could never fit together”.

[“Bogga kunni þetta utan að, þó breyttist sagan alltaf. Ný atriði bættust við og kollvörpuðu fyrri skýringum. Nánast ómögulegt að gera sér grein fyrir hvað var satt, hvað logið. Eða var þetta allt saman ímyndun? Þegar Daníel var orðinn veikur og sat í hornstól í stofunni, reyndi hún að spyrja, leitaði brota en náði aldrei að raða þeim saman” (Hringsól, 135).]

This question of how stories are told, again and again, and often in different versions (“I did not know that you were like the children who wish to hear the same story again and again”) (“Ekki vissi ég að þú værir eins og börnin og vildir heyra aftur og aftur sömu söguna” (Hringsól, 228)), is one of the leitmotifs of Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir’s works. The flawed memory keeps altering the story, memory being another recurrent theme in Álfrún’s writings. Together this is connected to ruminations about the nature of time, memory changes with time and time makes its own narratives. Álfrún wields memory like a weapon in her fiction, she uses memory to merge different worlds and periods, fragmentizing linear narrative. Thus the reader must try to approach her stories in the same way Bogga in Hringsól (Roundabout) (1987) does; seek fragments and try to puzzle them together, musing which ones of Álfrún’s narrators stories are pure illusions.

It could be claimed that Álfrún takes this narrative play the furthest in Hringsól, where we travel with Bogga through her memories from her childhood to her adulthood. The story starts in childhood and ends when Bogga has become old, but this does not mean that the narration is a linear description of the girl’s life. The text keeps flicking through time and space, similar to how the eyes wanders between memory fragments. Bogga, who is also called Ella, is born in a small coastal village. Her father is forced to place her in foster care with a well to do childless merchant couple, Jakob and Sigurrós, in Reykjavík. Bogga grows up there and finds it difficult to fit into this bourgeois lifestyle, it appears that she is not all that mentally stable, being passionate and sensitive, as well as highly imaginative. This is apparent from the way she perceives her surroundings in her home village. Above it looms a mountain appearing to the little girl as a woman: “A woman on a bier with her hands crossed over her ample breasts. That is how the mountain was”. (“Kona á líkbörum og krosslagði hendur upp við háan barm. Þannig var fjallið” (9)). This woman is also the mother in the child’s memory, having died giving birth to Bogga’s younger sister, and Bogga maintains that she saw her lying on a bier. The father protests: “Now you are telling stories […] She was never on any biers.” (“Nú ertu farin að skálda […] Hún var ekki á neinum börum.” (115))

Upon arriving to Reykjavík the child sees a dragon flying over the city and a frightening worm in the Tjörnin-lake. Her new home is beside the lake. War is about to start and political conflicts shake the small urban society, Bogga meets a young idealist and becomes pregnant by him, her foster parents want her to marry Daníel, Jakob’s younger brother, but Bogga refuses even though her lover turned out to married and has disappeared. She runs away from home and seeks shelter with Dísa, the former housemaid who had been fired for preventing Daníel from raping Bogga. Bogga raises her son Fjalar at Dísa’s place and has a short love-affair with a soldier who has Icelandic forefathers. But then the son dies in a terrible accident and Bogga’s sanity collapses. Jakob seeks her out in a hostpital and takes her back into her foster-home, where she becomes a kind of a house-maid. She is clearly not well. Daníel comes back home from his travels and they marry and have a child, but the girl Lilja cannot replace the son Fjalar and Bogga turns more and more inwards. For a good reason too, the situation in the house is peculiar for Daníel is, and has been for a long time, Sigurrós’s lover. Jakob dies and then later Sigurrós, then Daníel grows ill and dies. The major part of his story, during the time he spent in Europe, is told by himself when dying - and dead, for he haunts Bogga’s home, the big house by the lake, where she is now the sole occupant.

In this way I have puzzled together the narrative fragments of Hringsól, but probably my memory of the book has fooled me, adding events and wiping others out. The book could in fact be described in a completely different way, section by section, where the first part emphasises childhood, together with fragmented memories from later events, the next focuses on Bogga’s return to the house by Tjörnin, the third describes Daníel’s stay in foreign shores and the fourth part is the story of the period between the first and the second sections, Bogga’s time away from the house by the Lake, when Daníel is in Europe. That description, however, would not be any more ‘correct’ than the first one.

My narrations of Hringsól are typical linear narratives, whose purpose is to organise and arrange linearly and thus create a kind of escalation of cause and effect. Literary theories about narrative claim that its function actually is this, to create order out of the chaos of memories and events and thus infuse them with meaning; to organise them into a logical continuity of a beginning, middle and an end. According to these theories a story is made up of two parts, a story and a plot. The story contains the events themselves, the plot is how they are arranged into a form. The word plot (in Icelandic translated as flétta, literally: a braid) is particularly suited to Álfrún’s writings, as she braids together text and events, memories and fragments, forming a tight and elaborate weave. The loom is, as already said, made of memory itself, remembrances, and often some events or things suddenly and unexpectedly call forth diverse recollections, from diverse times and places. Thus it is the door introduced in the first page which gives the reader an indication of the struggle to come:

... do not know those who lived behind the door: made of a dreary wood. The girl did not know this yet, nor did she know how the door shut with a low sigh and never slammed. Until she ran, many years later, gone for good (she thought) from the house; nobody new about this of course when she stood there on the steps in front of a strange door and stared at the polished lock framed with the dark stripe, almost black.

[...þekki ekki þá sem bjuggu handan við hurðina: úr drungalegum viði. Þung. Um það vissi stelpan ekki þá, og ekki vissi hún að hurðin lagðist að stöfum með lágu andvarpi og skall aldrei. Nema þegar hún hljóp, mörgum árum seinna, alfarin (að hún hélt) út úr húsinu; um þann atburð vissi náttúrulega enginn þegar hún stóð þarna á tröppunum framan við ókunna hurð og mændi á gljáfægða læsinguna rammaða inn í dökka rönd, hérumbil svarta. (7)]

Later in the novel disappearance and death create a connection between time and space: Bogga hears that her lover is missing, possibly dead and from that memory the text wanders to another body, a woman’s body that plays a key-role in Daníel’s contradictory stories about his time in Europe. The woman’s name was Rósa and was perhaps a spy and in one place it is claimed that she “never forgot anything, her role was different and was supposed to remember what she saw or heard, commit to memory”. (“gleymdi ekki neinu, hennar hlutverk var annað og átti að muna það sem hún sá og heyrði, leggja á minnið” (284).) In this way the text is loaded with references to remembrances and memory, forgetfulness and illusions, the story of Rósa is told again and again and each time it changes - possible moving towards the truth, judging from a scene from late in the novel, but as has already become clear it is difficult to know what is Daníel’s imagination and what not.

Thus Hringsól circles around in time and memories, and this circling is in many ways reminiscent of the modernist literary characteristic called stream of consciousness. At times the narration unravels completely into fragmented memories from various times and morphs into a poem. An example of this is in the beginning of the second part when Bogga has returned back to the house, still recovering after the trauma. Bogga is sitting in her room and hears kicking feet and thinks about the war and the destiny of earth, which in turn remind her of her own destiny:

this earth which everybody thought that they had and had become unrecognizable, but of course nobody owned it even though a few continued to mess around with it, starting a game that nobody had understood and drew the others into a terrible maelstrom no way out of it

and no way to handle

sits and listens

booms and a hollow sound, something heavy had been thrown into a wall. Bottles broke. To risky to open a door or a window, not possible to know what waited outside, apart from ruthlessness

pain

loss

did not make this her business, not at all, and a window must not be opened, ugly words would barge in and

she would be pointed at

her fault a death

together with him one is alone just like the others and

the child

which Dísa was supposed to take care of

and Bogga’s eyes wander

allaround furniture and they are covered with faded rags like those who lived there in the basement of the house beside Tjörnin had gone for a long journey, had moved away

on the floor a suitcase.

[þessa jörð sem allir héldu að þeir ættu og var óþekkjanleg orðin, en vitaskuld átti hana enginn þóað örfáir ráðskuðu með hana, gengu til leiks sem ekki nokkur hafði skilið og drógu með sér hina í skelfilega hringiðu ekki úr henni komist

og ekki við neitt ráðið

situr og hlustar

dynir og holt dósarhljóð, eitthvað þungt hafði kastast á vegg. Flöskur brotnuðu. Ekki vogandi að opna hurð eða glugga, ekki að vita hvað úti beið, nema auðvitað miskunnarleysið

sársauki

missir

lét sig þetta engu varða, engu, og ekki mátti opna glugga, ókvæðisorð ryddust inn og

á hana yrði bent

henni að kenna dauði

með honum er maður einn rétt eins og hinir og

barnið

sem Dísa átti að gæta

og Bogga hvarflar augunum

alltumkring húsgögn og yfir þau breytt með upplituðum tuskum eins og þeir sem byggju þarna í kjallar hússins við Tjörnina væru farnir í langferð, hefðu flutt burt

á gólfinu ferðataska. (83-4)]

The tight vivid episodes in Af manna völdum (Caused by men) (1982) also contain modernistic characteristics. The first story describes a memory-fragment from the occupation in Iceland during the Second World War, a mother and daughter’s fear of a soldier and their flight from him. The story starts with an exclamation: “Oh my God. What happened to the child?” (“Guð minn góður. Hvað er að sjá barnið?” (9)) and then goes on to describe in short episodes how the mother is fetching water from the well and the bright sun reminds the girl of the flaming object that fell to earth and thus we move through memories to the city, an air raid. Now the family has moved into the country to avoid the army-barracks. On the way to the well a soldier addresses the mother and offers the child a chocolate but the mother becomes frightened and they run, first into the house, and then from it again and over a barbed wire fence and towards a neighbor’s house. A woman comes “running towards them, shouting...” (“hlaupandi á móti þeim og hrópaði...” (14)). Other stories are similarly tightly knit, while some are longer. The short story collection is subtitled “Variation on a theme” (“Tilbrigði um stef”) and that theme can very well be the war, or wars in general, and of course memories.

II

Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir is not a particularly productive author, nor can it be said that her books are generally known. Still, three of her novels have been nominated to the Nordic Council’s Literature Prize, Hringsól (1987), Hvatt að rúnum (Téte-a-téte) (1993) and Yfir Ebrófljótið (Across the River Ebro) (2001). The last two were also nominated for the Icelandic Literature Prize. Apart from these three Álfrún has published the novel Þel (literally the word refers to both a layer of wool and a disposition) (1984) and the aforementioned short story collection, Af manna völdum. Álfrún was over forty when she published her first work of fiction. At the time she had been a lecturer and a senior lecturer at the department of comparative literature at the University of Iceland, after having studied in Switzerland and Spain for many years. She is an excellent example of a scholar who has managed to conjoin the best of scholarship and fiction in her career, her works of fiction bear witness to a thorough knowledge of literary forms and styles, while never in any way appearing weighted down by scholarship.

It is difficult to place Álfrún’s work within any particular literary ‘ism’. Some modernist attributes can certainly be traced in many of her work, in particular Af manna völdum and Hringsól. On the other hand her third novel, Hvatt að rúnum, has many postmodern characteristics.

In this novel, Hvatt að rúnum, Álfrún continues to create a weave out of memories and stories. The title is an old saying, referring to a private conversation or a ‘tété-a-tété’ and this is what the narrator of Hvatt að rúnum does; she calls characters from the past to her, from another century and from another period in her own life, and makes them tell her stories.

The story is told in the first person by a woman who lives alone in a big house and is visited by two ghosts of the past. One of them is still alive, her former neighbor with whom she had a love-affair. That affair ended under terrible circumstances. The other ghost actually is a ghost, a young man from the eighteenth century which she tracks down and charms to her house. He tells her his story which is interlaced with the third story, a kind of a chivalric romance that he is reading. Thus Hvatt að rúnum has something of an ancient air, contrary to the earlier books, as it refers to the witch age, both in Iceland and Europe, superstition and legends, as well as carrying the literary inheritance of the chivalric romance, where magic and superstition abound.

Mysterious events also appear in the story from the present, primarily in the form of the ball of string stored in a tin and hidden in the house of the lover and his wife by an old woman, who asks the narrator to track it down. It is very important that this ball of string is treated correctly and it has its parallel in the eighteenth century story, where it is connected with witchcraft. Later in the novel it transpires that this is the story-line itself, or the many threads of the novel, wound up together by the narrator towards the end, against the wishes of the mysterious H (A), who is mentioned a few times in the story, mainly by the lover Jón Pétur, and turns out to be the author - although not necessarily Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir.

Jón Pétur is curious about the tin and the ball of string but “he must not know that due to the ball of string I have achieved a certain leeway and power, this I understood after my visit to Þorgerður. Rewound the ball and since then I have looked after it like a treasure. Tied to it hopes of freedom” (“hann má ekki vita að einmitt fyrir atbeina hnykilsins hef ég fengið visst ráðrúm og vald, það skildi ég eftir heimsókn mína til Þorgerðar. Vatt hnykilinn upp aftur og upp frá því hafði ég gætt hans eins og sjáaldurs auga mins. Batt við hann vonir um frelsi” (246)). The narrator has thus in the end taken the story-line away from the hand of the author, and this seems to be the magic of the story, or what? It is best to tread carefully when interpreting Álfrún’s many-layered plot, the threads she spins serve both to tangle and tie characters and give them “leeway and power”, and the reader is subjected to the same fate. Still, it is highly enjoyable to play at running the threads through ones hands, severing them and weaving together here and there.

Each story is told in the appropriate style and each is a powerful story in its own right, increasing in power as the story-lines weave magically together. The eighteenth-century story is about the young Stefán, who is an orphan raised in a vicarage. A foreign guest appears, Marteinn, who seems somewhat mysterious, and becomes Stefán’s friend. The priest is good to Stefán and teaches him to write, also giving him access to his books and this is where Stefán is introduced to the chivalric romance about Diafanus and his adventures with witches and sorcerers and a bald, beautiful woman, who is the former fiancé of Diafanus’s friend. After appaling events where among other things a body is discovered in a terrible way, Stefán goes to Europe with Marteinn (and a ball of wool in a jar) and there they meet with plagues and political disputes and get acquainted with a young man, Júlíus. Stefán catches the plague and suffers as well from a jealousy, and it is clear that his relationship with Marteinn is more than it seems. These two love-triangles, that of Diafanus, his friend and the bald woman, and Stefán, Marteinn and Júlíus, mirror the third one in the modern story, which is, similarly to the eighteenth-century story, told in the familiar non-lineral style of Hringsól (the chivalric romance is however, rather linear). When Jón Pétur arrives the narrator recalls their bygone love-affair, which was rather peculiar, as Jón Pétur was at the time married to the beautiful Nanna who encouraged him ardently to make love to his neighbor. The result of this was that the two women divided the man between them, each having him for a week at the time, and in addition seem to have had a fairly close relationship themselves. This uninhibited triangle ends with the suicide of the passionate and volatile Nanna, who had become desperate when her son was taken away from her. Recollections from this time merges with the return of Jón Pétur, and the conversation between him and the narrator, who, as already said, refer among other things to the mysterious H (A).

The author is possibly the representative of postmodernism, as such references to the author and the writing process are considered to be a particular postmodern symptom. Still, it would be wrong to claim that the role of the author or the postmodernism is a large one, as already stated the narrator manages to seize the story-lines from his hands. It is after all the narrator who calls forth the stories of Stefán and Diafranus and thus it is clear that she and the author fight for control over the story. When Jón Pétur demands recollections from the narrator she says that it is not her to decide. “Who then? A?” asks Jón Pétur and the narrator ansvers:

- He is in charge but you get to have a choice if you wish.

- He has me under his thumb.

- You should rather say that you are scared that I may get control over you. I bite my lip. This was imprudently said. Jón Pétur could befriend A and turn him over to his side, catching me in a web. This must not happen […].

[ - Það er á hans könnu en þú færð að ráða ef þú vilt.

- Hann hefur mig í greip sinni.

- Segðu heldur að þú sért hræddur um að ég nái tökum á þér. Ég bít á vörina. Gáleysislega sagt. Jón Pétur gæti komið sér í mjúkinn hjá H og fengið hann til liðs við sig, spunnið um mig vef. Ekki má það gerast […]. (97-98)]

This game of authorship is moderate yet effective. Álfrún treads carefully in this postmodern combination of narratives and story-lines, narrators and authors, skillfully weaving together an ironic approach to this authorship-game and a gravely serious one, for while the references to H (A) are at times quite frivolous and comical they are at the same time crucial to the story, which, as has been pointed out, does not happen until the author has written it: “Strictly speaking it is not right to talk about an event that has not taken place: it depends on how it is perceived. And I am not the one who controls it, it is A who thinks he is in charge. Two men in a tug of war over me.” (“Og strangt til tekið ætti að tala um atburð sem enn hefur ekki gerst: það fer eftir hvernig á hann er litið. Ekki stjórna ég honum né heldur H sem öllu þykist ráða. Tveir menn í reiptogi um mig” (44).)

The love-triangle motif is a repeated theme in Álfrún’s work. Her first novel, Þel, describes one such between three young people, Einar, Una and the narrator. Einar is a bit of an idealist, and so is the narrator, but when Einar goes to Europe to study, leaving Una and the narrator behind they become a couple and the narrator consents to become a bourgeoisie. The story is partly told from Una’s point of view in addition to chapters about Einar’s accounts of his stay in Spain, where political conflicts of the civil-war enter the story. Another love-triangle develops in Spain, between Einar, the mysterious Yolanda and her even more mysterious friend, who turns out to be her husband. Again we witness a journey through memories, as the story begins with Einar’s funeral. Afterwards the narrator goes to his house and allows the flood of memories to take over.

Hringsól also contains a love-triangle, that between Daníel and his sister-in-law, whom he has a love-affair with while her husband is a life and after he marries Bogga. This theme provides the novels with a strange emotional width and a continual underlying tension. The love conflicts also serve to reflect or interact with various political conflicts and thus these polished, carefully worked texts of the author become laden with passion.

III

Political struggles in Álfrún’s work is often related to warfare, all her works refer in some way to a war, eighteenth-century’s Europian conflicts in Hvatt að rúnum, the second world war in Hringsól and the civil-war in Spain in Þel, or both of the latter and others in Af manna völdum. Thus it should not have come as a surprise that sooner or later the writer would write a story about a war - but still it did.

Yfir Ebrófljótið is about the civil-war in Spain, a subject which is clearly important for Álfrún. The novel is a kind of a historical novel based on the autobiography by one of the Icelandic volunteers who fought the war, a war that can be described as a kind of an exercise for fascism before the Second World War. It should by now be clear that Álfrún’s writings are characterized by acute thoroughness. This thoroughness reaches its peak in this war about war and warfare, where descriptions of the soldiers’ lot is so detailed that the reader cannot help being drawn into this world of cold, heat and humidity, noise, lice and dirt, hopelessness, incomprehension and ideals.

The story is told by an old man Haraldur, who has had a stroke accompanied by a memory-loss and to coach his memory he recalls the year when he fought as a volunteer in the international brigade in the Spanish civil-war. As before in Álfrún’s writings we travel back and forth in time, both within Haraldur’s narration of the war and his youth, and then within the story of the homecoming, the love and marriage to his nurse, Hedda, and then of course between all these stories. Again we witness this unique and charming skill in creating connections between time-zones, Álfrún transfers her story effortlessly between its various stages and periods, from the everyday life of the old man who misses his wife, believing her to have left him, and into the carnage of the civil-war. Often it is the moon who is used to create connections, the old man stands in front of the window and looks for the moon, who is capricious and tricky, while at times showing mercy to soldiers who must either find a shelter in the dark or find their way in the moonlight:

My eyes wander to a windowpane and I go to it with one big stride.

There you are my good Moon, pale and reserved after your nightly drift, I am pleased that you were able to come ... the date remember ... Don’t go my friend ... not yet ... stay ... go and be damned then! Hide ... run and hide just like Hedda. I can get by without you let me tell you. Am doing quite well thank you, no need to worry unnecessarily. Actually it was I who had become worried about you, maybe you came uninvited ... intruder. That year, however, we were so grateful to you when we wanted to try and sneak over the Ebro in the shelter of the night.

[Ég hvarfla augunum yfir að rúðu og er kominn að henni í einu stökki.

Þarna ertu Máni sæll, fölur og fár af næturgöltri, gleður mig að þú skyldir sjá þér fært að koma ... stefnumótið manstu ... Ekki hverfa blessaður ... ekki strax ... kyrr ... farðu þá kolaður! Feldu ... hlauptu í felur rétt eins og Hedda. Ég kemst af án ykkar skaltu vita. Pluma mig prýðilega takk, óþarft að gera sér áhyggjur. Frekar að maður hafi gert sér áhyggjur af þér, komst kannski óboðinn ... boðflenna. En um árið vorum við fullir þakklætis í þinn garð þegar við ætluðum að laumast í skjóli myrkurs yfir Ebro. (37)]

Here the capriciousness of the moon is being compared to the wife’s disappearance, but the reader soon realises that she is dead, even though Haraldur thinks she has abandoned him. Sometimes the different storylines merge. An example is when the sound of explosions in Haraldur’s memory changes into a shrill sound of the phone ringing and later “the stillness of the room is […] broken by the cracks of the field guns.” (“kyrrðin í stofunni rofin af fallbyssuskotum.” (204))

However, the narrative does not wander as much here as in Hringsól or Hvatt að rúnum, the story of the war is largely linear, in accordance with Haraldur’s insistence that he must stick to the point and retrace the story in a sequence: “But my conversation with Ramón did not take place here, I did not get the opportunity to talk to him until a few days later, and Eugenio and I are still fumbling along down the hill, stopping at its bottom”. (“En það er ekki komið að samtali okkar Ramón, ég fékk ekki tækifæri til að tala við hann fyrr en fáeinum dögum síðar, og við Eugenio erum ennþá að paufast niður brekku, nemum staðar neðst í henni” (276).)

Later he breaks the sequence on a purpose, avoiding the day when he was wounded and instead recalls the stay in the hospital and the time together with his friend Andrés (whom he names his son after), who makes him promise to tell the story, like it was:

There is only one thing I wanted to ask you, and that his that you bear witness. That you will testify wherever you go and wherever you are to the situation like it is, not like the papers are reporting it. You have to tell about the betrayal to the republic, the betrayal of the British, the French, the Americans. Tell the truth. Do you promise?

[Það er aðeins eitt sem ég vildi biðja þig um, og það er að þú berir vitni. Að þú vitnir hvert sem þú ferð og hvar sem þú ert staddur um ástandið eins og það er, ekki eins og blöð segja frá því. Þú verður að segja frá svikunum við lýðveldið, svikum Breta, Frakka, Bandaríkjamanna. Segðu sannleikann. Lofarðu því? (435)]

Haraldur promises but then he gets cold feet and does not tell the story. One of the reasons why is that his hopes and ideals have burst, so it appears that Haraldur is unable to tell the story of his disappointment, shocked by what was to follow. In this way the novel is partly a critical assessment of political expectations and ideals, all of which Haraldur loses in the wake of the war. The purposelessness of the war is repeatedly referred to, its carnage and destruction which only lead to the victory of fasism and increased poverty and terrors for the nation.

David K. Herzberger article on Spanish historical novels after the civil-war offers an interesting way of looking at Yfir Ebrófljótið. Herzberger emphasises the role of memory in the novels and focuses on the period after Franco’s death, when writers attempted to break down the heroic myth that authors and historians of his period had created around the heroics of the war - with the fascist army in the role of the hero, of course. While the criticism in Álfrún’s novel is certainly not aimed against Franco’s mythos, it is clear that the novel is takes a clear issue against the myths of the military and warfare serving idealism, or rather, how idealism is used to throw a heroic light upon war. Thus there are some interesting points in Herzberger’s article that fit with Álfrún’s novel, such as the fictional way of making history subjective by mediating it through memories and thus subvert the myth of the heroic war. Herzberger describes the novel of memory thus: “the novel of memory portrays the individual self (most frequently, but not exclusively, through first person-narration) seeking definition by commingling the past and present in the process of remembering. This process may be activated either voluntarily or involuntarily” (37). Furthermore, he points out that in novels about memories the instability of the narrative as a truthful form is revealed, for as such a novel of memory is in a perfect opposition to the (fictional) stories of myth, who assumes power over the meaning of what is real and hence true: “the novel of memory offers a different claim on history and historical truths” (37).

Such comments have a striking similarity to many of the above remarks on Yfir Ebrófljótið. The history of the civil-war is being mediated through Haraldur’s individual self, which in addition is unstable, since his memory has suffered a shock. He asks himself: “To whom to I want to tell the story as it was? Myself? That would not be all that crazy. To clear the lie away. Then what is left? The truth? Everyone knows that it is relative and ... I am only killing time. Talking to myself like a baby”. (“Hverjum vil ég segja eins og er? Sjálfum mér? Það væri hreint ekki svo galið. Ryðja burt lyginni. Hvað situr þá eftir? Sannleikurinn? Allir vita að hann er afstæður og ... ég aðeins að drepa tímann. Tala við sjálfan mig eins og barn” (50).) Haraldur is in some way looking for explanations for his decicion to become a soldier, and the process of remembering is rather against his own will, for he has never wished to tell the story. Still it becomes clear that some parts of it have been told to Hedda, who has apparently asked a lot of questions, while never hearing the entire story - and although Haraldur is now willing to tell her the whole story now, it is too late.

Thus a strange atmosphere surrounds this narrative of remembrance, recalling other novels by Álfrún, in particular her narrative technique. As Soffía Auður Birgisdóttir points out the narrators of Álfrún are continually being called for a ‘tété-a-tété’ with their memories, more often than not against their own will: Soffía Auður points out how the memories haunt Bogga, who is not all that excited about these recollections, and as already explained the narrator of Hvatt að rúnum tracks Stefán down, but he in turn warns her about the consequences of this and thus seems unwilling to give up his memories. The narrator herself is reluctant to recall past events from her own life, but cannot avoid that when Jón Pétur comes to her: “I do not want to talk about a fire, want to postpone it, postpone the pain.” (“Mig langar ekki að tala um bruna, vil slá því á frest, slá á frest sársauka.”) She is sleepless and tired: “about to throw all of this away and refuse to contine, whatever A might say, even though I hate quitting something I have started. Would mean that I could not get out of the prison that I have created for myself. And I who had prepared all this so carefully”. (“að því komin að kasta þessu öllu frá mér og harðneita að halda áfram, hvað sem H kynni að segja, þótt illa sé mér við að hætta í miðjum klíðum. Hefði í för með sér að ég losnaði ekki úr prísundinni sem ég hef sjálf komið mér í. Og ég sem hafði undirbúið þetta allt vandlega” (241).) Memories haunt the narrator of Þel, but here the resistance is little, as he takes his time to remember after the funeral.

In an article about the role of fiction and authors Álfrún points out that “in fiction people do not come “straight to the point” […] most things are being paraphrased, even veiled in the mantle of figurative language, innumerable threads and patterns are woven and the mind is invited to play a game” (485). Just as Haraldur goes back and forth across the river Ebro in a pointless and unintelligible war the stories of Álfrún travel back and forth in time and space, between characters and between different periods in the life of the characters. She uses the form of the novel of memory to grapple with the compelling form of the linear narrative which assumes the myth of truth and formalism. Her characters’ memories and their recollections of other people’s narratives are being unraveled, just like unwinding a ball of thread which is then rewound again and the thread spun into other threads, as when the explosions of the war breaks the silence in Haraldur’s living room or when his son barks like a machine gun. Thus Álfrún periphrases and spins a story and a narrative, veiling it into the mantle of figurative language - the river, the ball of string - and offers the reader endless play with words, memories and fiction.

úlfhildur dagsdóttir

Sources

See “Articles” in the menu on the right.

David K. Herzberger’s article can be accessed on: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?index=22&did=1770653&SrchMode=1&sid=3&Fmt=6&VInst=PROD&VType=PQD&RQT=309&VName=PQD&TS=1134422969&clientId=58032. Last viewed 30.10.2022.

Articles

Criticism

Dagný Kristjánsdóttir: “Magt mod kærlighed – kærligheden mod magten”, “Det spøger i litteraturhistorien”

På jorden 1960-1990, Nordisk kvinndelitteraturhistorie, bind iv, ed. Elisabeth Møller Jensen et al. København, Rosinante 1997, pp. 460-461

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 441, 442, 542

On individual works

Hvatt að rúnum

Jón Hallur Stefánsson: “Ordets magi : Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir fletter sin roman af nutid, fortid og eventyr = World spell : Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir uses the present, the past, and a fable to weave her novel”

Nordisk litteratur 1994, pp. 29

Tristan en el norte

Kjær, Jonna: “Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir. Tristan en el norte”

Mediaeval Scandinavia 1978-79, vol. 11, pp. 298-304

Marchand, James Woodrow: “Álfrún Gunnlaugsdóttir. Tristán en el norte” (review)

Scandinavian studies 1983; vol. 55 (number 1, Winter), pp. 71-73

Yfir Ebrofljótið

Dagný Kristjánsdóttir & Soffía Auður Birgisdóttir: “Å svike eller bli sviktet av idealene : nomineret til Nrodisk Råds litteraturpris 2003 = Have you betrayed your ideals – or have they betrayed you? : nominated for the Nordic Council’s kuteratyre Award 2003”

Nordisk litteratur 2003.

Awards

2018 – The Knight's Cross of the Icelandic Order of the Falcon, for her contribution to Icelandic literature and university level education in the field of literature

2009 - Fjöruverðlaunin - The Women´s Literature Prize: Rán

2008 - DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Rán

2001 - The Icelandic Broadcasting Service Writer´s Prize

1985 - DV Literature Prize: Þel

Nominations

2008 - The Icelandic Literature Price: Rán

2003 - The Nordic Council Literary Prize: Yfir Ebrofljótið (Across the Ebroriver)

2001 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Yfir Ebrofljótið (Across the Ebroriver)

1995 - The Nordic Council Literary Prize: Hvatt að rúnum (Pokus)

1991 - The Nordic Council Literary Prize: Hringsól (Roundabout)

Fórnarleikar (Game of Sacrifice)

Read more

Siglingin um síkin (The Canal Cruise)

Read more

Rán

Read moreLe Passage de l'Èbre

Read more

Im Vertrauen

Read more

Hvað rís úr djúpinu? : Guðbergur Bergsson sjötugur (What rises from the Deep? - Guðbergur Bergsson at Seventy)

Read moreSagan og undraborgin

Read more

Yfir Ebrofljótið (Across the River Ebro)

Read more

Över Ebrofloden

Read more

Sálumessa yfir spænskum sveitamanni (Requiem for a Spanish Farmer)

Read more