Bio

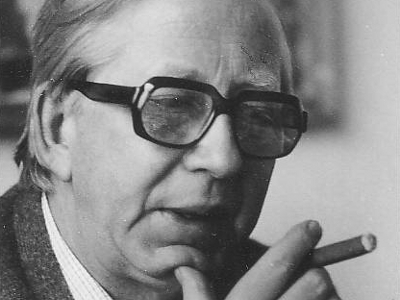

Björn Th. (Theodór) Björnsson was born in Reykjavík on September 3, 1922. After finishing secondary school in Reykjavík, he studied art history at the University of Edinburgh from 1943 – 1944, The University of London from 1944 – 1946 and The University of Copenhagen from 1946 – 1949. Björn had a long career as an art-historian, teacher and writer, and sent forward numerous books on art-history as well as novels and essays. He taught art-history at Iceland's Art and Craft School, Iceland's Teacher's College and The University of Iceland. He was a member of the board of The Icelandic Broadcasting Company, and was one of the members of the preparatory committee for Icelandic television from 1953 – 1968, and was a representative at Iceland's Educational Board from 1968 – 1974. Björn was president and vice-president of the Writer's Union of Iceland from 1958 – 1964, a member of the editorial board for the literary magazine Birtingur 1958 – 1963 and head of the Art Museum at the University of Iceland from its foundation in 1980 until he retired in 1997.

Björn wrote numerous articles for Icelandic and foreign magazines and journals and did documentaries on cultural matters and history for radio and television. Björn's first novel, Virkisvetur (Fort's Winter) was published in 1959 and received first prize in a competition held by Iceland's Educational Board. His historical novels continue to be very popular in Iceland, and his books on Icelandic and foreign art-history are also widely read. Two of his novels are available in Danish translations.

Björn Th. Björnsson passed away in Reykjavík on August 25th 2007.

From the Author

From Björn Th. Birgisson

Half way through college I had developed a considerable interest in history. Not the history of kings and wars, but the history of the daily lives of people in centuries past. Shortly after matriculation I got hold of Troel Lund´s great work, Dagligt liv i Norden [Daily Life in the Nordic Countries], and that made me realise that the official history of Iceland, the one taught in schools and written down in books, was only superficial muttering, with its tale of political wheeling and dealing of influential people at the Danish court, the beaurocrats and their ombudsmen dotted around the country, local chiefs and "great men" get a mention and a few wealthy farmers also. But there is no insight given into the daily lives of the nation, their cooking, eating habits, clothing, how the children where raised or the practise of medicine. The nation itself was completely lost in these historical "studies".

After a few-years stay in Copenhagen, the former capital of Iceland, I developed an interest in the students and other Icelanders who staid there for long periods of time and the conditions they lived in. The result was a book written in 1961, Á Íslendingaslóðum í Kaupmannahöfn. In that book I came to the conclcusion that there were not only students who scraped a living there, but also a larger group of forced inhabitants in His Majesty´s city: professional slaves, men, even youths, women and children, were incarcerated in the torture chambers of stockades, clinks, and prisons. Many hundreds of Icelanders suffered this horrible fate, sentenced there for little or no reason, except perhaps their poverty, hunger, or naive ignorance.

Soon after I found myself in Seeland´s historical archive on Jagtvej street, Landsarkivet for Sjælland, and there I discovered a large and beautiful book which was not as pretty inside. It was Sclaven-Rolle in der königlichen Residence und Festung Copenhagen [The Slave List of the Royal Residence and City Copenhagen], all carefully written in German. The torture masters in Denmark were all German, as they have thought to excell in that area of expertise. As I turned the pages of this great tome, I saw on every page the names of Icelanders, their age, the sentence, and punishment. This fateful book now became my key to the time-consuming research that was to follow, both in Copenhagen and at home in Reykjavík. This endeavour resulted in my first historical novel, Haustskip, 1975, re-published many times since, once in a Danish translation.

In this research and in the book that followed, it is patently obvious what a blatant lie we have all been taught at school, that it was the Danes who oppressed us cruelly and mercilessly. The trade monopoly was, of course, a heavy burden on the nation, but it was the result of the absolute monarchy that Icelandic officials, both laymen and learned, agreed to by signing the treaty at the historic meeting in Kópavogur [Kópavogsfundinum] in 1662. The naked truth is, that it were the Icelandic ruling classes, officials of the Danish government, and the rich landowners that oppressed the common people in a cruel manner and they waged a war of obliteration against them by sending impoverished people to lifelong slaverey in the torture chambers of Copenhagen. Time and again do the top officials here in Reykjavík got told off for such behaviour, it was as immoral as it was illegal. But still the autumn ships sailed, taking with them these poor souls, women and children, to suffering and death.

In my historical novels that followed I have looked at the material in a similar fashion. I have rarely tackeled it straight through official sources, but rather looked for them in the secret depth of human lives. This is true of the novel Hraunfólkið, but more so of Falsarinn, Salka and Brotasaga, in all these books I take a look behind the official curtain of history and sense people in their daily work, their happiness, hopes and, unfortunately, sorrows. At times such methods have been called "to look at life from below". From that point of view I think we are more likely to find the truth, rather than in the glossy images of the official history of Iceland.

Björn Th. Björnsson, 2002.

Translated by Dagur Gunnarsson

About the Author

The History of the Historical Novel: On the Works of Björn Th. Björnsson

The historical novel, i.e. a novel that is based on written documents, oral accounts or recent events is a relatively new phenomenon in its present form. Its rise began in the 19th century, and one could name Les Misérables by Victor Hugo (1862) as a good example of a story, which deals with major events in the history of France from 1789, up to the time when the book was written. The reader gets an insight (which never tries to be impartial) into various revolutions and uprisings, the Napoleons, and the living conditions of the common people, which no historian would have been able to conjure. Indeed, one of the strengths of a historical novel is that it can describe events in a more vivid way than academic history can, and hence has a better chance of carrying the reader along, conveying the information in the form of a story.

In his book, Íslenskar heimildabókmenntir: Athugun á rótum íslenskra heimildaskáldsagna (Icelandic Documentary Literature: A study of the roots of Icelandic documentary novels) the literary theorist Magnús Hauksson focuses on two of Björn Th. Björnsson´s books, Falsarinn (The Forger) and Haustskip (Autumn Ship). Magnús´ recipe for analysing documentary novels is to compare various elements which are normally considered characteristic of either fiction or historical studies, and see where they intersect or whether elements of one form are more predominant than those of the other.

At the beginning of the essay, he puts forward the hypothesis that documentary novels are on the border between fiction and history. This leads to a number of questions. How do authors conduct their research and how do they see their own text? Can one see what kind of text they think they are writing? What does the form of the works say about what weight history and fiction carries in them? Are techniques associated with fiction predominant, or is the narrative historical? Are the style, characterization and staging used in a similar way to novels? Furthermore, is the text mainly logical and explanatory, a discussion of documentary sources and interpretation? (Magnús Hauksson, 1996, p. 148)

This fine recipe of Magnús´ will not be followed here, except to such a limited degree that it is clear that the outcome would be quite different. Each book will first and foremost be viewed individually, without considering its historical value, or to what extent it is a product of the author´s imagination. Yet it is clear that in Björn Th. Björnsson´s books, the narrative style, characterization and staging use the methods of fiction.

Björn himself explains his method of writing documentary novels in the following way: "Where the documents end, the mind and probability have the stage to themselves" (Solka, p. 63).

The author does this in a few places in his books: he comes forward and discusses the inevitable gaps in historical documents and the questions they raise. We who are only here in thought and are immaterial except for the curiosity of history; we can slip in through windows or doors without anyone noticing us. Yet we cannot write anything down, let alone take photographs, we must only let our eyes absorb the things we find, in case a grandchild should later ask us something like this: Were they rich and great in those days, the grandsons of Valdi í Skógum?

(Falsarinn, p. 189)

No doubt many will ask themselves the question of whether it is not a form of historical forgery to fill in the gaps, like Björn Th. Björnsson does in his books. Do documentary novels damage the real study of history? The author and historian Helgi Ingólfsson says in his article „Sagnfræðin sem skáldskapur" ("History as Fiction"), which was published in Sagnir, a history journal, that:

Few history books are so inadequate that they do not give some insight into human nature and most works of literature have some kind of a historical framework. But as literature places much more value on personal experience and human nature, they are in many ways closer to psychology and philosophy, although I have not heard anyone ask if literature might be useful or harmful to those disciplines.

(Helgi Ingólfsson, 1995, p. 40)

Therefore Helgi´s conclusion seems to be that documentary novels are not harmful to the field of History. Furthermore, Helgi maintains that he has heard „more than one Icelandic historian declare that reading historical novels in their teenage years was a decisive factor in their choice of subject." (Helgi Ingólfsson, 1995, p. 41).

Björn Th.´s Style

Björn Th. Björnsson is well known for his work in the field of Icelandic art. He wrote Íslensk myndlist (Icelandic Art), which is still today the ultimate resource on Icelandic visual art, and he has also written books on historical places like Copenhagen and Þingvellir. He has also made an acclaimed TV series about the historic haunts of Icelanders in Copenhagen. One could therefore say that Björn is on home ground when he writes novels based on historical documents, which take place in Copenhagen or at Þingvellir. He conjures the spirit of each era with a phenomenal attention to detail (as far as one can see from the viewpoint of a 21st century reader) and conversation between people from any societal class come alive in Björn´s hands. The art historian´s touch is apparent when it comes to describing housing and furniture, the architecture and dress style of each era. Björn is at his best in these descriptions, pouring from his bountiful fountain of wisdom. Björn´s keen eye for the conditions of the poor gives his books a universal relevance and his harsh criticism of religious authority is hard to miss. He obviously likes to show all the worst aspects of corrupt power, and Haustskip is a particularly good example of that.

Virkisvetur (Winter in the Castle)

Set in and after the middle of the 15th century

Björn Th. Björnsson´s first attempt at a historical novel was his participation in a prize competition of the Education Committee of Iceland "for a new Icelandic novel". After reading the submitted manuscripts, it was the "unanimous opinion of the jury that one of the manuscripts stood out, the novel Virkisvetur (Winter in the Castle)." (from the book cover)

Jón Espólín wrote in his Chronicles of the 15th century „that during it scholars lost the study of history, poets the ancient sensibility, farmers their agricultural skills, laymen their previous freedoms, and shore-dwellers their visiting trade ships, but bishops became like kings, before its end.“ (Íslandsárbækur, Formáli 2. deildar (Iceland Chronicles, Preface to the 2nd Part), taken from Björn Þorsteinsson´s book, Enska öldin, (The English Century, Mál og menning, 1970, p. 11)). This century has been called the English century because English ships began to travel here in this period; up until that time Norwegian merchants had been the sole traders here. „The new business which Icelanders were making with foreign nations caused a change in the economy and contributed to the accumulation of wealth by individuals. Icelandic society was slightly transformed in the 15th century; it was the period of the "rich men" in this country." (Björn Þorsteinsson, 1970, p. 11) Virkisvetur tells of men who became extraordinarily wealthy: Björn "the rich" and Guðmundur "the rich". The son of one of the two men and the daughter of the other fall in love, but because of a dispute between their fathers, it does not seem likely that they will be allowed to marry.

Virkisvetur tells of Andrés Guðmundsson, the son of Guðmundur "the rich" Arason at Reykhólar and his relationship with Sóla, Solveig Björnsdóttir, the daughter of Björn Þorleifsson the rich at Skarð and Ólöf Loftsdóttir the rich. Andrés has a half-sister who is also named Solveig, daughter of Guðmundur by his former wife, Helga Þorleifsdóttir, sister of Björn the rich, who has passed away at this point. Sóla and Andrés are not related, although he calls her "his cousin", but Helga, former wife of Guðmundur was her paternal aunt.

Into Andrés and Sóla´s relationship comes the dispute between their fathers; Guðmundur the rich traded with English merchants. Previously, Björn and him had both been "of the same mind: that is, intent on forcing the king to allow free trade" (Virkisvetur, p. 29), but now they are not on speaking terms.

It had never been as clear to Andrés as now, that his father´s trade with the English carried maximum penalty in the laws of the land, and its only shield of protection was his wealth. According to his accounts, which had now been placed, sealed, inside the letter container, his father owned all lands from Gilsfjarðarbotn in the east, through Barðaströnd in the west and Dýrafjörður in the north, and east of the heath all lands in Kollafjörður and along Steingrímsfjörður; in total close to being just twenty shy of two hundred.

(Virkisvetur, p. 34)

In 1446 Guðmundur the rich was sentenced to exile "and everything he owned should go to the king!" (Virkisvetur, p. 90), which was a considerable amount: great and many lands. Consequently, Andrés´s situation changes drastically and the likelihood that his and Sóla´s love has a happy ending becomes very small. If he succumbs to the power of her father and brothers, they will never regard him worthy of Solveig, but if he fights them, they will not give their daughter and sister to their enemy. He always seems to face two options: "one which he desired and another which opposed it?" (Virkisvetur, p. 155-6)

Despite the confiscation of his father´s property, Andrés has a right to the land of Fell in Kollafjörður and runs a farm there, while trying to reclaim his father´s property from the grasp of Björn the rich, who has now become the king´s representative in Iceland. For this purpose, Andrés travels to Althing one more than one occasion, and with support from his brother-in-law Bjarni, manages to claim a part of Solveig´s inheritance after her mother. (Virkisvetur, p. 136)

When Björn the rich at Skarð is killed by English merchants (1467), people are convinced that Andrés and Bjarni have arranged the killing. This further decreases the chances that Andrés and Solveig will be united. "Never will the fine maiden commit the blood sin of marrying her father´s killer," people said to one another. (Virkisvetur, p. 158)

Towards the end of the story Andrés prepares to defend himself against his enemies. Andrés and his men are thrilled to finally be in a battle like the ancient heroes. "They did not mention it to other people, but they themselves knew that the time of heroism had returned, and here they were, in the place which formerly sheltered Þorgeir and Þormóður and Grettir." (Virkisvetur, p. 220)

The author clearly enjoys slipping various facts into the account and does it so subtly that the reader is delighted when s(he) recognized the reference, but does not suffer if s(he) does not know the thing or the event in question.

Andrés fetched the horses and lead the grey one to a tall turf, holding the stirrup firmly while abbot rolled onto the horse´s back.

- Shouldn´t I carry your sack? That damned book seems mighty heavy.

- Thank you. Yes, this is a great book, with beautiful lettering. It was written up north in Víðidalstunga some fifty years ago, but now its home is at Skarð. Ah yes, by now many treasures have found their home there. It has stories of ancient kings and a chronicle.

(Virkisvetur, p. 85)

An interesting description, both of a book and of wealth!

This book gives a taste of what is to come in Björn Th.´s books: Magnificent nature descriptions, precise furniture and clothing descriptions, and above all faithfulness to historical events, which are fictionalised in such a way that they seem very fresh. Readers recognize either– depending on how well read they are - events, characters or the spirit of the times, but Björn Th. manages to weave a story which is exciting and descriptive of both the era and the individual.

Haustskip (Autumn Ship)

Set in the middle of the 18th century.

Haustskip came out in 1976 and it is the second time Björn tries his hand at a historical novel after a long hiatus from fiction writing. It is an account of various cases of petty crimes in the 18th century, from the year 1745 to 1770, based on judgments, parliamentary books and census records. The title refers to the fact that those who were convicted in Alþingi in the summer months were sent abroad on an Autumn ship to serve hard labour in Stokhus, Spindhus or Bremerholm.

Haustskip is probably Björn Th. Björnsson´s least accessible book. The language for the most part is the elevated Danish official style, with frequent references to judgments and documents reflecting the bureaucratic style of the time, as well as being peppered with Latin references. At times it is quite difficult to follow the antiquated language, but at the same time the reader can enjoy imagining the sound of Björn´s voice, deep and sonorous, educating us about Icelandic criminals´ stay in Copenhagen.

The author often uses written records and those references are a bit of a hindrance for untrained readers. These are either in German or in such specialised Danish that nothing like it has ever been taught in Icelandic primary schools, where most Icelanders receive their language training. Björn uses his resources in a unique way: always marking in the margins where each reference is taken from. This makes the account credible, and seeing the scribbles in the margins give it a scholarly feel. The reader feels that s(he) is reading over the shoulder of the scholar himself.

All kinds of politics are woven into the stories of petty crimes and harsh punishments, along with the social situation, weather patterns and natural disasters. Thus it becomes quite clear that when famine rages as a result of volcanic eruptions and bad weather (an eruption in the volcano Katla in 1755, sea ice 1754-56), people will admit to crimes rather than dying from hunger out in the open field. During these hard times many were forced to steal food, which carried harsh penalties, and as the number of people resorting to theft grew, the tougher the sheriffs became in their judgments. When a war over Schleswig-Holstein was imminent and the Danish king wanted to strengthen his troops, Icelandic sheriffs saw an opportunity to get rid of local riff-raff and send them away to be cannon fodder. Skúli the sheriff feared depopulation because of the starvation death toll and transportation of criminals abroad, and he brought about reforms, so that men were ordered to serve their convictions by working in the Innréttingar (Enterprises; the first Icelandic factories Trans.), rather than in Copenhagen, and he argued that a prison needed to be established in Iceland. (Haustskip, p. 250)

The modern reader may think that there are worthier things in human society than a prison, but in terms of historical significance, this was a major achievement.. Fines would no longer be paid out of the country, nor would the income of the country´s richest monastery; property and income taxes would now for the first time since Viking times remain in Iceland.

(Haustskip, p. 277)

Incompetent, greedy and lazy sheriffs are the main theme of the book. They cannot be bothered to go to Alþingi and condemn men to flagellation or even death back home in the provinces, not hesitating to carry out their own judgments as well (p. 151), "but the younger and more law-abiding sheriffs bring them to court" (Haustskip, p. 180).

What, respectfully, should sheriffs go to parliament for? For what purpose should they waste time and resources in transporting their delinquents on a journey of many days and weeks, to this wet, rough lava field to languish there over nothing, for the best part of the harvest and then be ushered back home none the wiser?

(Haustskip, p. 232)

Sheriffs are too mean to feed the prisoners, they use them as free labour and of course it never occurs to them that they may be wrong or that the harshest punishments should not always be dealt out for ridiculously small crimes. They are also ignorant of prison matters in Denmark and sentence men to incarceration in Bremerholm long after it has closed in 1741 (Haustskip, p. 25), sentence males for a stay in the women´s prison Spindehuset, and so on and so forth, so that when the prisoners arrived in Denmark, prison authorities had trouble allocating the prisoners to the right places.

When they pass sentences, they muddle everything up from sheer unfamiliarity; they convict either for Brimarhólmur, which they see as a kind of a general slave camp, although a prison by that name and in that place had then long since been closed down; they sentence in one and the same word for the Copenhagen prison and Citadellen Friderichshavn and hardly know whether either of them exists or what the difference is.

(Haustskip, p. 74)

It follows that it is also hard to trace what became of the convicted individuals after they arrived in Denmark.

Because of the Icelandic authorities´ unfamiliarity with the Danish prison system and the unclear wording of the judgments, many will have gone to the Christinshavn prison who were in fact meant for the Copenhagen Stokhus.

(Haustskip, p. 78)

The author ridicules people in positions of power, but he has great sympathy for the underdog. The story is peppered with various anecdotes. People are mentioned in the story only so that he can tell funny stories of them, rather than for the purpose of plot development. For instance, the author says about Jón Grunnvíkingur that he was very gullible, although the exact words are:

There was never a great delay before a whisper of such news travelled to Ögur, where the sheriff Erlendur Ólafsson was in charge, which was always willing to take every story to be the truth, no less than his brother Jón Grunnvíkingur, who has believed more fibs than any other Icelander.

(Haustskip, p. 64)

Digressions like this can be highly entertaining.

Haustskip is Björn´s least accessible book. He has mastered the 18th century manner of speaking quite impressively and shows brilliant command of language not seen anywhere else. This can be slightly problematic for the reader, the need for a dictionary to understand it, but it also makes the book unique.

Falsarinn (The Forger)

Takes Place in Three Centuries, in Iceland, Denmark and in Chile.

Falsarinn is more accessible for the general reader than for example Haustskip, yet Falsarinn is the only one of his novels that takes in multiple eras and countries. It is divided into 5 parts and the first three parts take place in separate places in separate times: the first part in Chile in 1886 – 1893; the second part in Iceland in the years following 1782; the third in Denmark in 1894. The last two parts of the book travel continuously between these three places and periods. Each part of the book tells the story of one man from the same family. In this book, Björn Th. himself makes a brief appearance, as he in fact did in Brotasaga, although here it is a more direct way.

Falsarinn tells the story of Þorvaldur Skógalín, his extended family and descendants, spanning two centuries. Þorvaldur is convicted for money forgery and is sent to Denmark to serve a life sentence. In this sense one might say that Falsarinn is a sequel to Haustskip, a sequel where the story of the descendants of the convicted man is followed all the way to our times. The connection is also visible in how the author lets Þorvaldur stay close to the events of Haustskip, even though he is not a character in it.

Nor had Þorvaldur heard any news, although it was closer to him, of how his compatriots were now whipped in the Copenhagen Stokhus, in a tighter succession than ever before; then were one after the other carried dead in an open sailcloth outside the city walls.

(Falsarinn, p. 282)

Þorvaldur was himself in the Cronenburg castle by Helsingør at the time. The readers have to read the book in order to find out whether he died there. One thing can safely be disclosed, however: Þorvaldur changed his name, and was therefore not listed as Þorvaldsson in documents. Many others have done this and it was long thought to be classy, although Þorvaldur may not have done it for the sake of prestige, in the situation he was in. Left alone in the room were these two youngsters, Þorvaldur the master draftsman from Skógar, shackled and sentenced to death, and the boy Jón Jónsson.

Later they would both take the names of farms, Jón after his father´s large farm, naming himself Espólín; Þorvaldur after the deserted hovel at the edge of the heath, calling himself Skógalín.

(Falsarinn, p. 166-7)

Jón´s birthplace was Espihóll, but Þorvaldur came from Skógar in Þelamörk in Hörgárdalur by Eyjafjörður. Þorvaldur´s descendants were distributed around various countries, which is the reason why Falsarinn takes place in so many countries.

Although Falsarinn is set in various countries of the world, some of the main characters are brought together for a dinner party in Copenhagen, shortly before the year 1900. "At the centre of the table sat the cousins, Alfred Viggó, the great merchant and consul in Conception, newly awarded the medal by King Christian, and Júlíus Vilhelm from the Exchange, with Teresa Lúdmila between them." (Falsarinn, p. 189) There is also the painter Axel Schovelin, grandson of Þorvaldur Skógalín. He "inherits the artistry and becomes a royal painter", but his brother "inherits all that has to do with money and becomes the government chancellor".. (Falsarinn, p. 375) Then their sons switch roles; Alfreð Viggó, son of Júlíus Schovelin becomes a merchant and a consul, but Júlíus Vilhelm, son of Axel becomes an economist and president of the Royal Exchange. It is the son of Alfreð Viggó´s daughter, who knocks on Björn Th. Björnsson´s door in 1979.

Hraunfólkið (The Lava People)

Set in the first part of the 19th century.

Hraunfólkið is about the people at Þingvellir, the priests who lived there with their staff, and the farmers in the area. One farmer in particular causes becomes the bane of the priest´s existence; he has countless children by adultery and cannot be brought to justice, because he is the sheriff.

- It is my suspicion, that your children in Skógarkot do not all spring from the one and the same source.

- From which opening should they then have come, reverend?

- You keep four young female workers but no male worker. It seems to me that your wife Sigríður´s births have become rather frequent, inside the two hundred and eighty days, which master Brynjólfur has counted.

(Hraunfólkið, p. 69)

This is from a conversation between reverend Páll Þorláksson and the philanderer Kristján. Pál´s son, reverend Björn, is the fourth reverend who tries to talk some sense into him but is no more successful than the others.

"- You think that you know the speech by now, Kristján Magnússon. You think it is the speech that my late father gave you, and my brother Einar and Einar Sæmundsson. And which you can then forget!"

(Hraunfólkið, p. 200)

But Kristján gets his way. This is the main conflict in Hraunfólkið; it is not a story of sweeping events. Perhaps what makes it most interesting is how characters who were involved in historical events (or were behind the case clash here – Rasmus Kristján Rask – and the story, like Jörundur the Dog-Day King who rides to Þingvellir on his way north through Kaldadalur), and knew important people: "The last people who remember the golden era of Skálholt and Alþingi in Þingvellir." (Hraunfólkið, p. 133) Ragnheiður Finnsdóttir, mother-in-law of reverend Einar, was married to the last lawyer at Alþingi and her brother was the last bishop of Skálholt.

The bishop´s daughter, the bishops sister, the lawyer´s widow, the lawyer and poet´s Eggert Ólafsson´s sister-in-law; there were no other such people in this country. At home in Meðalfell, one of her two daughters, Ragnhildur, now sixteen winters old; the other daughter, Guðríður, four years older, is with the Madame´s revered brother, the Sheriff Steindór Finnsson in Oddgeirshólar in Flói. And then there is Finnur, now in Reykjavík, who has quit his education.

(Hraunfólkið, p. 55)

That Finnur is the son of Ragnheiður; Finnur Magnússon who later became a professor and keeper of the secret Danish archives. Then there is also the very famous brother of reverend Páll, Jón á Bægisá himself, the same who translated An Essay on Man by Alexander Pope and John Milton´s Paradise Lost.

Character descriptions do not get much better than the one of reverend Páll, who always experiences anxiety attacks when he has to travel around the parish, let alone any further, and tries what he can to avoid all travelling. Usually, however, he gives into pressure and attends to his duties, but when his presence is expected when his son is ordained in another province, he turns back midway.

- Get out of these clothes, go to bed he said to his Guðfinna when she looked at him flabbergasted, as he approached the house. – Frightfully poorly my dear Guðfinna! A bit sickly I believe, , and he uncharacteristically lied to save himself from the scolding. He was very glad when he had taken off the robes and laid under a blanket and sheepskin. Still he felt a little sting in his conscience when she served him a hot drink in bed. (Hraunfólkið, p. 92)

Reverend Páll receives his share of tragedies, losing his wife and children. His wife dies aged 32, leaving behind 6 children and shortly after that, their son dies. "Yet another loss of life, and with great sorrow, in the Þingvellir church family." (Hraunfólkið, p. 69) Reverend Páll builds himself a coffin, which is placed on a pedestal in the church. When his son Einar is hired to replace him, which means that reverend Páll will not be forced to leave when he retires, this is thought to be an act of great kindness on behalf of the bishop. " - Old Páll can then be laid to rest in his own coffin, in his own yard, people said, and forgot for the time being that the coffin was not sturdy enough to hold a man." (Hraunfólkið, p. 99) Reverend Einar arranges for the coffin to be removed from the church, after it has been sitting there for seven years. Shortly thereafter, Einar receives a much better parish with the help of his mother-in-law, Thingvellir is then given to another reverend who remains there for seven years, when he is driven away by his parishioners, with whom he has waged a constant battle. His successor is Björn Pálsson, reverend Einar´s younger brother. We follow his story until he gives up his post due to the leprosy that causes his death, but it also describes of the direction the next generation takes.

The reverends´ ongoing battle with the sheriff runs through the whole story, but the main value of the story lies in its mixture of perceptive descriptions of beautiful nature, and sarcastic depictions of the poor farming conditions of the Þingvellir land.

Þingvellir is once again in the crosshairs when this is written; with the recent publication of Jón Karl Helgason´s book, Ferðalok (Journey´s End), which describes the exhumation of the bones of Jónas Hallgrímsson in 1946 and their burial (or not) in the national burial plot at Thingvellir. Björn Th. Björnsson has himself commented on this bone transplantation and talks about it in his book, Á Íslendingaslóðum í Kaupmannahöfn (The Historic Haunts of Icelanders in Copenhagen). In Ferðalok, the Þingvellir land does is not given high marks, because Halldór Laxness has said: "laws on churchyards in this country were completely disregarded, so that he [Jónas from Hrifla] could ever since count among his heroic deeds to have buried Einar Benediktsson in the location in Iceland which is one of the worst suited for a burial site, the Þingvellir field, either wet or soil-less [...] where it was customary to stake the heads and bodies of executed criminals." (Jón Karl Helgason, 2003, p. 125).

To the reverends in the Þingvellir parish, the quality – or rather the low yields of the land was the principal issue, people today are more concerned with the sacredness of the place and its magnificent nature. Hraunfólkið contains masterly descriptions of Þingvellir´s nature; it is obvious that the author cares deeply for the place.

The abundance from nature´s bosom was oblivious to the sorrows of a weary priest. Over the forest and the Lake, you witnessed the pleasure of life vibrating from every string. A she-fox ran carrying a bird in her mouth to her kits, the spider ecstatically span her hunting net across cracks and openings, and the Great Northern Diver had no words to describe the splendour out on the Lake and laughed a long laughter into the sun.

(Hraunfólkið, p. 50)

Hraunfólkið is an easy and entertaining read, the reader easily gets an overview of people and issues.

Solka (Solka)

The Story is Set in the Later Half of the 18th Century.

The Setting is Skagafjörður.

Solka tells the back-story to the oft-discussed disappearance of reverend Oddur á Miklabæ.

The author takes a different view to the one traditionally accepted when writing about Oddur á Miklabæ. In folklore, Solveig is described as a lovesick maid who stalks him and continues her persecutions as a ghost and finally kills the man she could never have. This folkloric explanation has in latter times been doubted, a recent example being Ragnar Arnalds´s stage play on the subject, where his sympathy clearly lies with Solveig.

In Björn Th.´s version of the story of reverend Oddur and Solveig they love each other, but he is a great coward. Because of his family name, but not least his cowardice, Oddur agreed to marry the woman who had been arranged for him and this caused Solveig to kill herself. Oddur had always been mentally unstable and this plays a crucial part in his fate. Björn Th. is clearly keen on exorcising the ghost, which has haunted the story of the disappearance of reverend Oddur of Miklibær.

The story begun here has never been told before, because it has always been hidden beneath a cloak of folk beliefs and a frightening ghost story. For anyone who would peek underneath that cloak there can still be found some stepping stones for crossing that dark stream of folklore. Those stepping-stones supported the guesswork of the good men who cared more about what happened on earth than apparitions of the dead or hallucinations in midair.

(Solka, p. 6-7)

Solveig Þorleifsdóttir has all the author´s sympathy, but Oddur the bishop´s son is described as insane, as he sometimes runs to the mountains because he was beset by "occasional insanity ... but he claimed not to know why he went off like that." (Solka, p. 7) He is also a spineless individual who never takes initiative in any matter. He lives with Solveig but does not marry her, does not want to become a reverend, but placidly accepts his lot when his father, the bishop, allots to him Miklabær church and the post of reverend there.

Oddur is then forced into marriage with Guðrún Jónsdóttir in Goðdalir and his protests come to nothing, since he is not considered responsible for his actions. "-When a man has verifiably shown himself to be mentally ill, my dearest brother-in-law, so as you have repeatedly done, then his parent´s authority stands, as if he were a minor." (Solka, p. 162). Yet, Oddur´s mental illness does not seem to suffice for him to be considered unsuitable marriage material!

Woven into the story is the fate of Sigþrúður "the blind" at Staðastaður, the daughter of Skúli the sheriff´s brother, who will become a benefactress of Solveig and Oddur. Her son, reverend Bjarni Jónsson at Mælifell, also proves a good friend to them. It is during a conversation with Sigþrúður, that Oddur mentions Guðrún Gottskálksdóttir, who Björn Th. later writes about in Byltingarbörn.

The author of Solka places the couple on a farm in Vesturdalur (which runs south from Skagafjörður) that he calls Dalkot, on the premise that most things point to "some farm or a cottage owned by the Goðdala church. But where the documents end, the mind and probability are given free play."(Solka, p. 63) There is, however, plenty of documentation, as one can see from a bibliography at the back of the book and there are also direct quotations to other stories of Oddur in Miklibær, but they are few and neither overshadow the story nor put a special mark on it.

Brotasaga (A Fragmented Story)

Set in the period between 1869 and 1934.

The Setting is Iceland and Hull, England.

Brotasaga is about the fate of a poor and abandoned girl. The story begins when the protagonist´s mother, Guðrún Eiríksdóttir, flees the tyranny of her master at Torfastaðir in Grímsnes in 1869. On the way she leaves her two-year-old daughter in the care of Dómhildur, the matron of Elliðakot. Then the daughter, Anna Guðrún Sveinsdóttir, is placed in care in "Vilborgarkot by the river Hólmsá, where she is registered as a ward of the county. (Brotasaga, p. 22). In her confirmation year Dómhildur also moved there "and cared for the girl like a mother as lovingly as any unrelated person could." (Brotasaga, p. 30)

Anna Guðrún was by now completely alone in the world, her father having drowned "on the Reykjavík shore", and her mother Guðrún, who had some time earlier become a maid at Syðri-Reykir in Mosfellssveit, had now died there, at just 33 years of age.

(Brotasaga, p. 31)

Anna Guðrún grows up and when she nears the age of thirty she gets a job with Gunnlaugur in Oddgeirsbær, who runs a fishing business. There she meets Halldór Diðrik Runólfsson. Halldór proposes to Anna Guðrún and wants her to move with him to Hull, where he plans to get rich from fish trading like James White, who he works for. They move there but nothing goes as planned. Anna Guðrún has two sons there but the health of one of them is very frail after an accident. They move back home and Anna Guðrún seeks shelter with Gunnlaugur, her former employer. There she has one more son, and then moves with Halldór to the Westman Islands, where she has her fourth and last child in six years, a daughter who is one of the sources for Brotasaga.

On the Westman Islands it was customary that men named their houses after the places where they bought their boat motors from and the house, which Anna Guðrún lived in, was therefore named Björgvin (Bergen), which made her "Anna í Björgvin".

Anna Guðrún learns to sew, which comes in handy when she lives in Hull and also later on when the family falls on hard times. In the beginning she drifts from one farm job to another, just as her mother had, but has the good fortune to meet kind-hearted people who treat her well. From her surrogate mother Dómhildur and Málfríður, who shares her situation in Hull and the Westman Islands, to James White and Eldeyjar-Hjalti, men who significantly make up for the sorry excuse for a man she is stuck with as the father of her children.

And when Anna Guðrún had her second son baptised in Fríkirkjan on the 3rd of December, who was sprinkled with water and by the grace of the Saviour named Halldór Magnús Ingiberg, Gunnlaugur in Oddgeirsbær himself was the child´s godfather and arranged it with the reverend Ólafur that the parents were in his books called "a married couple in Bjarnaborg", she 32 years old, even though the former employer knew himself all about their problematic marital status.

(Brotasaga, p. 147)

It was to Gunnlaugur, who both sat on the town council and the poverty council that she fled to during the "Ingvars weather" when she thought Bjarnaborg would be burned down with her in it, and with him and his wife she stays for quite a while, or until she returns to Halldór.

Almost an uncomfortably long time passes from the time when Anna Guðrún and Halldór meet and he promises her the world, until she finally sees what kind of a man he really is, even if there are times where she tells him how poorly he performs at most of his projects. She is displeased at how their move to Hull was not as previously agreed with the employer, James White, and tries to egg Halldór on to pursue his rights. When he says he is not comfortable with "demanding something like that from Mister "Væt"", she replies that she will do it then, for she will not take this kind of treatment anymore. She can well start wearing the trousers in this household, he does not do such a job at it: "You have so far not taken care of anything, not the wedding and not the boy´s medical treatment. And you were not even at home when I had him." (Brotasaga, p. 134).

The author´s account of how Anna Guðrún scolds her husband has some basis in reality, he has witnesses: "When this woman was on a roll she had command of some of the strongest language which I have heard in my time, - and there was even some suspicion that her speech carried power that went beyond the words themselves," the author quotes after Ási í Bæ. "Others have been saying for a long time, that men feared the scolding of Anna í Björgvin and felt that it even came true in a colossal way." (Brotasaga, p. 134). Nor did it diminish the fearful respect Anna Guðrún enjoyed that she was said to be psychic.

I sometimes say that someone is coming, but they say no, that they are not expecting anyone and not in this kind of weather. But then someone comes. Maybe with two dogs, just like I said.

(Brotasaga, p. 24).

Brotasaga is Bjorn Th.´s only story that takes place in the 20th century. It is also his least dramatic story, because it lacks or has in short supply many of the things which made the other books so fine: Nature descriptions, descriptions of clothing and houses, of greedy authority and an oppressed public. Instead this book is a fine story about the struggles of a working class woman, and is fine as such.

Hlaðhamar (Hlaðhamar)

Set in the first part of the 18th century.

The Setting is Hrútafjörður.

Hlaðhamar is about Árni Kársson, a poor, bad-tempered and ignorant unfortunate. He was recently married to Gerða á Hlaðhömrum, for the sole reason that he thought she was wealthy, but unknowingly he has a daughter who is an infant at the beginning of the book. The child´s mother hands the child over to his care, which causes great hostility between him and his new wife, resulting in Gerða´s moving out from him. He is left behind with his daughter.

Then something happens, which no one had ever seen and no one would ever believe, that Árni Kársson knelt forward on one knee, smiled and tickled the child under the chin with two fingers. Sveinborg stood over them, inflating with motherly pride. Árni straightened up and reached for the leash of the red one, who had now calmed down quite a bit and was grazing. Árni looked variously at the child or the woman, shifting like he was embarrassed. Finally he asked:

- On what does such a human being live, Borga dear?

(Hlaðhamar, p. 25)

The first part of the book mainly consists of descriptions of Árni´s novel methods for keeping an infant alive, despite his utter ignorance of how to care for a child.

Soon a boy named Jón begins to make regular visits to Hlaðhamar and he is very good with children. Later he will be a fateful presence in Guðrún and her father´s lives when he and Guðrún fall in love. When they first meet she is an infant and is kept in a box to keep her from wandering off and endangering herself. Jón asks Árni why she is kept in a box.

- Then I know where to find her and she is not in the way of anything. She likes it.

- Can I pick her up?

The boy Jón did not wait for an answer, but picked the girl up and ran out with her into the grass field. There he lay down on all fours, and Árni saw, to his considerable surprise, that she crawled with him in the grass.

(Hlaðhamar, p. 61)

Árni and Guðrún first encounter with Jón foreshadows what is to come; Árni believes Guðrún is content where he puts her, but Jón wants to whisk her away and she happily accepts it.

From the first page Árni is described as a brute. When he embarks on bringing up his daughter alone, he develops an excessive love for her. She is the only thing he has ever owned and he never wants to let her go. He is ignorant and therefore cannot teach his daughter anything, but later she meets other people, and then she no longer believes her dad is the centre of the universe like she did before. Árni is not happy with Jón´s interest in Guðrún and sees him as a personal threat.

- Hello, Árni, said Jón from Hlíð, cheerful as always.

- What are you skulking around here for, asked Árni, an unfriendly grumpiness erupting from his words.

- Well, I was mainly just looking for Guðrún´s she-lamb, the black spotted one, if she had joined the herd.

- What the devil is it to you? I am not aware of her having any she-lamb, neither a spotted one nor any other kind! You would be wiser to stick to your own business, and leave my daughter alone! Enough have you been idling around her! (Hlaðhamar, p. 184)

In this aspect Árni resembles Victor Hugo´s protagonist, Jean Valjean in Les Miserables. Jean Valjean adopts a little girl, who he brings up as his daughter. When she is of age and men begin to desire her, he does everything to avoid them. She falls in love with Marius Pontmercy and when Jean Valjean finds out he plots to kill Marius (but actually ends up saving his life). What Árni and Jean Valjean have in common is that they have never loved or been loved except by their daughters and the thought of losing their love is unbearable to them.

Jean Valjean only had fatherly love for Cosetta. He loved her like his daughter, he loved her like his mother, and he loved her like his sister. But as he had never loved a woman differently, never loved a wife, those kinds of emotions were also subconsciously intermingled with his love, unclear, blind, angelic, heavenly and divine. His emotion was love and affection for Cosetta, hidden and pure like a gold vein in a mountain.

Now the reader can imagine the situation. A marriage was out of the question, not even a marriage of the soul. But yet it was certain and for sure, that their fates were wed. When Cosetta, or in other words childhood, was excluded, Jean Valjean had, in all of his long lifetime not encountered anything that he could love.

(Hugo, 1988, p. 233)

The similarities are also underlined by the fact the stories, Hlaðhamar and Cosetta and Maríus´s love story, take place in a similar period, or in the first part of the 18th century.

When Gerða and Árni resume their cohabitation, Guðrún from Hlíð moves in with Jón and his mother, Valgerður. This Árni cannot accept and tries to get Guðrún back home to him, whatever it takes.

... never has there in Strandasýsla or Húnaþing started up such harassment and persecution as that which now took place by the hand of Árni á Hlaðhamri against the people at Hlíð. Even though he was frail he besieged the farm like an invading army, knocked on doors and walls, shouted threats... And for all that the siege did not let up, no matter if it was day or night.

(Hlaðhamar, p. 193)

Árni has his way in the end: he manages to drive Guðrún and Jón apart for good, but has then to accept the consequences of that action.

Byltingabörn (Children of the Revolution)

The story takes place in about ten years just before the middle of the 16th century.

The Setting of the story is Skálholt and the characters are the priests there, the bishop and his successor, with servants.

Byltingarbörn came out on the millennial year of Christianity in Iceland. It describes the events leading up to the reformation in Skálholt and the ordination of Gissur Einarsson as bishop and follows him until the day he dies (1548).

Skálholt is a vast complex, with an architectural layout so convoluted that people who live there cannot even find their way through all the corridors. Hence they each lead their separate lives and do not communicate with each other for days and even months at a time. In the various dusty corners there are things brewing which are best kept secret; preparation is underway for a religious uprising, planned by men who support the bishop, who is now old and blind. Leading the group are Oddur Gottskálksson (who translated the New Testament into Icelandic 1540) and Gissur Einarsson, who are both Lutherans.

Dietrich von Mynden, viceroy and sheriff of Bessastaðir comes (1539) with an order from the king to convert to Lutheranism, "a ban on sacrifices and prayers to saints, ban on Hail Mary´s, and church services are required to be in the country´s own language." (Byltingarbörn, p. 27) The butler at Skálholt, Father Eysteinn "the strong" Þórðarson hides all sharp instruments when he hears that Dietrich von Mynden is on his way to Skálholt. Eysteinn then allows his men to arm themselves "with the right of the holy Skálholt Church" (Byltingarbörn, p. 85). They attack the sheriff´s men, kill him and his men, and bury them. This event may affect Oddur and Gissur´s plan to seize power at Skálholt.

If news of this reaches Copenhagen before the bells of Our Lady´s Church ring out the great tidings, Gizur Einarsson will never become bishop of Skálholt. And then all our struggle would be lost.

(Byltingarbörn, p. 88)

The author is able to convey quite well what the public, the upper as well as the lower classes, found to be frightening and foreign about the new religion and how it changed the world picture without necessarily strengthening the faith. That everything which was valid before, is in the new tenet seen as worthless. To read the New Testament in you own language only means having to struggle through the endless genealogies, which is not very constructive, compared to having the priests teach you about the word of God.

- In the new tenet, according to Gizur and his men, sin is between a man and his own soul. Then it will no longer be possible to pay your way out of it with indulgences or donations, or to leave it behind in some confession booth!

(Byltingarbörn, p. 51)

The Skálholt men plan on becoming priests and preach "the unadulterated word" (Byltingarbörn, p. 27) Not everyone is very steadfast in their new faith however, and some seem to like the method of the first Icelandic Christians five hundred years earlier, and be allowed to practice their old faith in secret. Reverend Eysteinn the butler belongs for example to the men of the new religion, yet he still prays to "the blessed bishop Þorlákur" (Byltingarbörn, p. 31) and kisses the shrine where his bones are kept. Veneration of the bones of saints is precisely one of the things that Lutheranism fought against.

With the Enlightenment, schools and the ability to read the word of Christ, people in the country soon became self-sufficient. It also spelled the end for these awful pilgrimages, to Kaldaðarnes and to the bones of bishop Þorlákur here, where one could follow their tracks by following the stiffened bodies of old people and children! People now attend their own church and listen to the un-crazed word of God!

(Byltingarbörn, p. 158)

Guðrún Gottskálksdóttir is Oddur´s sister, the voice of Catholicism in the book, who becomes desperate when she realized how Lutheranism views the old form of worship:

" – Is then the blessed Mary at Hofstaðir nothing more than wood and rags? Is the head of John at the Hólar altar no more than silver and bone?"

(Byltingarbörn, p. 18)

Guðrún finds herself between a rock and a hard place, herself a convinced catholic but her brother and her lover, Gissur Einarsson are both Lutherans, even though they conceal it as well as they can while the old bishop, Ögmundur Pálsson is still alive. Bishop Ögmundur names Gissur as his successor and he becomes the 34. bishop at Skálholt. A marriage contract is drawn up between Guðrún and him, since priests are allowed to marry in the new religion.

Even though Gissur and Guðrún are married, the daughters of the former viceroy (who died in 1534), Hannes´ daughters Magdalena and Katrín, compete with each other for Gissur and are aggressive in pursuing their goal. Their brother, Eggert (later viceroy), is in the service of bishop Ögmundur and then Gissur. Gissur´s women troubles occupy a fair part of the book, but at the same time they say a lot about the spirit of the times.

As usual, the author inserts fun factoids, the hunting of the Great Auk is explained in a way that gives this embarrassing case for Icelanders a new dimension.

- I have here in my sack a box filled to the brim with Great Auk fat. No butter comes close to the lovely Great Auk fat.

- Pardon the ignorant one, dear Ráðhildur. Which fat did you say?

- The lovely Great Auk is nothing but fat. When I peel its coat off and boil it in my big pot, the rendered fat is so thick, that it can be lifted up in one piece like a lid on a pot. And melted together with the broth, it is the tastiest spread on Gods blessed earth!

- Say, how do you hunt this bird?

- We never hunt it. It sits on peninsulas and promontories, and any child can outrun it. All you need is a small snare around the neck. Yes, my good man. It is less trouble turning this blessed feathered beast into meat and fat than a slaughter lamb in autumn! And the coat! This bag here is sown from one..

(Byltingarbörn, p. 39)

Conclusion

The books discussed here have been enormously popular. The first book, Virkisvetur, sold out instantly and had to be reprinted right away. It was out if print for twenty years, until it was republished some time after the second book, Haustskip came out. All Björn Th. Björnsson´s books are constantly on loan from libraries, as the staff at the Reykjavík City Library can attest to. Apart from his research and writing of historical novels, Björn Th. has also translated quite a few books. His translations have been of the same high standard as everything else he has done.

Outstanding features of Björn Th.’s books are the nature descriptions. It does not matter whether he is describing a bird or a mountain; the reader is able to picture it vividly and is carried away. Björn Th.´s flair for storytelling makes History with a big "H", into an entertaining story and a thriller. "The artistic illusion of documentary novels is that we feel we are among historical characters, in a bygone era." (Magnús Hauksson, 1996, p. 222). If that is true, then Björn Th. must be a great illusionist.

There are good reasons to encourage people to read Björn´s books, and it is easy to see why he is one of the nation´s most popular authors.

© Bára Magnúsdóttir.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 241

On individual works

Byltingarbörn

Isaacson, Lanae Hjortsvang "Byltingarbörn. Skáldsaga" (review)

World literature today 2002, no. 76, pp. 194

Awards

1990 - The National Broadcasting Service's Writer's Fund

1989 - The DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Minningarmörk í Hólavallagarði (Marks of Memories in Hólavallagarður)

1959 - The Ministry of Education Novel Competition: Virkisvetur

Nominations

1993 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Falsarinn

Jarlhettur: Sagan um Þórurnar tvær á Þingvelli (Jarlhettur: The Story of the Two Þóras in Þingvellir)

Read more

Glóið þið gullturnar (Glow golden towers)

Read moreStofugólfið á Ströndinni

Read more

Haustlauf (Autumn Leaves)

Read more

Byltingarbörn (Children of the Revelution)

Read more

Hlaðhamar

Read more

Brotasaga (A Fragmented Story)

Read more

Solka (Solka)

Read more

Hraunfólkið (The Lava People)

Read more