Bio

Einar Már Gudmundsson was born in Reykjavík on September 18th 1954. He received a B.A. in Comparative Literature and History from the University of Iceland in 1979 after which he moved to Copenhagen to do graduate work in Comparative Literature at the University of Copenhagen.

Einar's first book, the collection of poetry Er nokkur í kórónafötum hér inni? (Is Anyone Here Wearing the Korona Line?), appeared in 1980. In 1985 he received first prize in a literary competition held by Almenna Bókafélagið, Book Publishers and Book Club, for the novel Riddarar Hringstigans (The Knights of the Spiral Staircase). On top of his novels and poetry books Einar has also sent forward non fiction books, such as books on the economic crash in Iceland in 2008. His books have been translated into several languages and the widely acclaimed novel Englar alheimsins (Angels of the Universe) received the Nordic Council's Literary Award in 1995. Fridrik Thór Fridriksson's movie which is based on the book premiered in Reykjavík on New Year's day in the year 2000. Einar Már also cowrote the scripts for Fridrik Thór's movies Börn náttúrunnar (Children of Nature) and Bíódagar (Movie Days). In 2013, Einar Már received the Swedish Academy's Nordic Prize for his literary contribution.

Author photo: Hörður Ásbjörnsson.

From the Author

I: Óli, have you noticed how small heads the doves have? Don you think they have no brain?

Óli: No, they’ve got wings. What should they have a brain for?

I: You mean it’s better to have wings than a brain?

Óli: I think it’s best to have wings on the brain.

This conversation between two boys is from my second novel, Vængjasláttur í þakrennum (Wingbeat on the Rooftops). It appeared in 1983. I don’t know whether I thought about it so clearly then, but over the years this has become a goal, to look at the magic in reality and the reality in magic.

You mustn’t think about things too much either. Thus I say as the anarchists: Be realistic-and do the impossible.

But still I say: Fiction is a search for an inner meaning in the outer world and an outer meaning in the inner world.

All this is about connection, relationship, love. "All you need is love".

Everything resides in fiction, and yet fiction is nothing special, not one marked off phenomenon.

That’s why the poem and the story go hand in hand.

I have gone back into childhood and history or tried to understand the whirlpool each moment brings us.

Yet I cannot say that I seek my subjects out, they come to me, knock on the door and thus the race begins; to quibble the mind, to settle in the arms of the past: this is a journey on a bus called story.

The journey leads into the unknown, but there things begin to have a meaning.

I was born in Reykjavík, in a time of change that has taught me to look in various directions. The new age was being born but the old one was not yet dead. The world of the media non-existing, rather much freedom. Many children. Much life.

This human existence never found its way into (hi)storybooks. Thus I am interested in a (hi)story that is not considered a (hi)story.

But now I’m obsessed with history, the story that wasn’t included in the history we were told. More I cannot say at present but take my leave with a small part of a poem:

From "Homer the Singer of Tales":

One rainy afternoon,

on a ship from a much travelled dream,

Homer the singer of tales arrived in Reykjavik.

He walked from the quayside

and took a cab that drove him

along rain-grey streets

where sorry houses passed by.

At the crossroads Homer the singer of tales turned

to the driver and said:

''How can it be imagined

that here in this rain-grey

monotony lives a nation of storytellers?''

''That’s exactly why'', answered the cab driver,

''you never want to hear

a good tale as much as when the drops

beat on the windows.''

Einar Már Guðmundsson, 2000.

Translated by Jóhann Thorarensen. Poem translated by Bernard Scudder.

About the Author

Þröstur Helgason:

Confusion of the Dominant: On Einar Már Guðmundsson

I

...what rationalism views as two polar opposites

fiction sees as a single whole,

fantasy and reality belong in the same hat.

This Einar Már Guðmundsson says in his book Launsynir Orðanna, (Bastard Sons of Words) (1998) which includes articles and thoughts about fiction. The intuition and inspiration are important medicines for Guðmundsson in the art of storytelling. He is probably one of the few Icelandic writers of his generation (and the younger ones) who would not swear off all romantic ideas about inspiration and other elements of genius. And how could he when he says things like these: "The creative force is most likely based more on a vision into secrets than a knowledge of the laws of nature." There are secrets behind fiction according to Guðmundsson, some wizardry occurs that we do not know to the fullest, and do not perhaps have to know, it is sufficient for us to know that "the art of storytelling ... has its roots in man's soul," as Guðmundsson says. (1)

While reading Guðmundsson's works critics have usually been occupied with dialogues like the ones in the sentence above between spirit and matter, adventure and reality. And it is important to see this as a dialogue between opposites (concepts, ideas) but not a struggle because Guðmundsson's texts occur on the borderline where opposites dissolve as such, run into each other. Or as Guðmundsson himself has said "labels often end up on the wrong product. What does, for example, a concept like fantastic realism mean? That there is realism without fantasy? That fantasy is something that is added to reality? That neither reality nor fantasy can be both at the same time?" (2)

No, fantasy and reality belong in the same hat in fiction.

II

This subtle deconstruction of (a rational) dualistic thinking places Guðmundsson in a postmodern context. In a brand new article it is even maintained that Guðmundsson's first collections of poetry (which were also his first books and appeared in 1980 and 1981) mark the beginning of this condition in Iceland. (3) The collections reflect their contemporary late-capitalistic age but also criticise it, the consumption, the introversion, the lack of meaning, harshly. The state of disintegration in postmodernism appears, among other things, in reference to the unstable symbols of mass-culture and how Guðmundsson positions himself on the borderline between the centre and the margin of literary history. In the collections we can thus find references to the ancient Greek tradition, Shakespeare, and respectable contemporary literature as well as Hollywood movies, pop, rock, and punk. And since everything is mixed together it all seems to undermine each other. Only a few things remain and the mind only recalls pictures that were never taken, as in the poem "in memoriam." (4)

We can continue to read Guðmundsson within the (broken) frame of postmodernism in his next books, the three novels that placed him among the stars in Icelandic literature in the early nineties. In them the breaking of the dual (correct) thinking continues and we also find there some sort of a reference to the literary heritage or a recycling of it. (5)

The present is still the subject matter. So is urban life, though in a different way or from another point of view. The books explore how a child perceives the city, lives and plays in it. The city was a popular subject among Icelandic novelists early in the century when the nation flocked to the city from the country in hope for a better life. These stories described the loss of paradise and fallen angels. The city was seen with eyes dazzled by country bliss, it was a bed of lust that pulled the nation from its origin, from the clarity of the valleys to the darkness of the noise of the city where traditional values were turned upside-down. It can be said that in Guðmundsson's trilogy the effects of these growing pains of the city are dealt with. We can see, up to a point, a correlation between them and the growing pains of the boys who are the main characters in the books.

The first novel is called Riddarar Hringstigans (Knights of the Spiral Staircase) (1982). The story is told from the point of view of a six-year-old boy, Jóhann Pétursson, and deals with his adventures and pranks in a suburb of Reykjavík sometime in the seventies. But it is perhaps not less about the problem of existing, of being a small boy in the grey, cold, and lifeless world Guðmundsson had also described in his poems. This is an insipid world of concrete and asphalt and, even though the childlike imagination often brings smiles and warmth into it, it wins in the end. Thus the boys are brought into reality when one of them, one of the knights, falls from a spiral staircase in the medieval castle, which is in fact a weatherproof concrete house,and is killed.

The second novel, Vængasláttur í þakrennum (Beatings of Wings in Gutters) (1983), also deals in parts with a clash between two worlds, the fertile and creative world of the child and the dead-cold world of concrete. Here creation and destruction are at odds. In the beginning of the novel dove-cotes are built in the neighbourhood. In the boys' eyes this is a whole village of winged life that gives them almost unlimited freedom for play and work. But at the end of the novel this world of glory is torn down completely since nature, in the form of dove guano,has become too importunate with the asphalt, in the neighbourhood housewives' opinion. In the last chapter of the book a deluge takes place that clenches the neighbourhood's streets of life.

In the third novel, Eftirmáli Regndropanna (Epilogue of the Raindrops; 1986), a picture is drawn of an insipid and dry world of grown-ups in the neighbourhood. The perspective in the novel is different from that of the two earlier ones. Jóhann Pétursson is nowhere near and we get to know life in the neighbourhood through some familiar characters of the older generation from the earlier novels. We follow them through the dreariness of the days. Very few things occur; the neighbourhood has lost the boys' games. It is only the rain that beats on the inhabitants all through the book, their houses and asphalt.

Growing up is a hard reality. Like the collections of poetry these books can be seen as a critique on the late-capitalistic urban life. Here the spirit of life and the power of imagination in the child's mind are posed against the numbness that characterises the alienated city (citizen's) life.

III

The mode of narration and style in these three novels is quite varied and perhaps it can be said that Guðmundsson was searching in this matter. The fast, concise, and dramatic narration of the first novel, which clearly reflects the youth's enthusiasm for action and play, gives way for symbolism in the second one. In the third the narration revolves around the highly metaphorical style, the story disappears into the language so to speak. These experiments with modes of narration continue in Guðmundsson's next book, the short story collection Leitin að dýragarðinum (Looking for the Zoo) (1988). Here the style becomes more down-to-earth, more objective, and more moderate in every respect. The figurative language is not as playful and the narration is heavier even though the thematic performance is often characterised by play and humour. The book received variable criticism. In fact it and the following novel, Rauðir Dagar (Red Days) (1990), have been talked of as a kind of an anticlimax in Guðmundsson's works. The mode of narration in Rauðir Dagar is realistic and fast paced but many of the critics said they missed the metaphorical style of the trilogy. The book tells the story of a young country girl from up north, Ragnhildur, who comes to the city in the late seventies in search of a new life. The main subject matter is the rebellion of '68 and Ragnhildur's relations with a group of radicals. It is possible to find a thematic similarity with Rauðir Dagar and the three collections of poetry (that is the left-wing radicalism), Guðmundsson published in the beginning of his career, but the novel considerably lacks the same impact they have. The same is true of Klettur í hafi (Rock in the Ocean) (1991) a collection of poetry Guðmundsson published in collaboration with the painter Thorlákur Kristinsson (Tolli). Considering the tempest that took place in the early books there is stillness in this one.

We can see the sum of Gudmundsson's experimentation in the book that has carried his fame the furthest, Englar Alheimsins (Angels of the Universe; 1993), which received the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 1995 and has been translated into several languages. Sum is perhaps not the right word, it is probably more correct to say that in Englar Alheimsins Guðmundsson best reaches harmony between form and subject matter. Again the subject matter is a clash between two worlds but this time it is not the world of the child and the grown-ups but that of the insane and the sane. The story itself best puts the main theme into words: "[W]e who are committed to asylums and kept in institutions, we have no answers when our ideas are at odds with reality, because in our world other people are right and know the difference between right and wrong" (4). (6)

The narrator in Englar Alheimsins has a rather unique position since he is no longer among the living. Páll Ólafsson relates his life from the time he is forced into the world against his will and until he leaves it again of his free will forty years later. Páll is born on the same day Iceland joins NATO, when "the world was like a madman in microcosm: schizophrenic, split in two, the world picture a chronic misconception" (12), but it becomes precisely his own destiny to be caught in the clutch of insanity. The book describes how schizophrenia gradually takes hold of Páll's life and finally seizes control over his inner life. He is placed in a mental institution, Kleppur. Kleppur is the best known (or the most notorious) institution for the mentally ill in Iceland (transl).

There he is sedated and it is the beginning of the end for him. His nature is repressed, it is driven backwards into the depths of the soul and then he is released. He becomes "one of those invisible citizens that the wind sweeps along Austurstraeti" (150). But although the darkness has left his soul the longing for life has been extinguished.

The mode of narration in the story is marked off by the narrator's unusual position. A voice from beyond (in first person singular, past tense) tells us a story of how it is to live in another world within our world. In fact, the narratorial voice is twofold because the story constantly changes between points of view by having Páll, while living, tell the story (also in first person singular, but in present tense). The interplay and overlapping of these two (and in fact many) voices - the former endowed with sane reason but the other(s) insane - splits the text and thus formally reflects on its subject matter. (7)

By simplifying just a little, the text can be described as being schizophrenic. Its fluctuation between a realistic (rational) narration and a poetic (irrational) one underlines this split but some of the clauses in the text can be seen as pure poetry.

The story can be interpreted as a critique on a society that excludes insanity, but that would be a simplistic and limited reading. It is impossible to disregard a sociological reading but, as has already been pointed out, the story is paradoxical or polyphonic in its discussion of insanity, and thus it demands a lot of the reader. Frequent changes in perspective show very different sides of insanity which makes the reader get a feel for society's incompatible views of it. (8)

This complex and structural web lies beneath the surface in the story and does not interfere with its progress. The enormous popularity of the book is no doubt due to how well this web is woven into the story and in a convincing but also a humorous discussion about the life and position of an insane man.

IV

In Englar alheimsins we can most certainly read a rather radical breaking of the dualism of rationalism, that was mentioned at the beginning of this article, a breaking of accepted opposites such as reality and fancy, life and death, sense and the lack of it. That way we are back to Guðmundsson's postmodern reference. (9) In his next novel Guðmundsson is back with the urban motif. In Fótspor á himnum (Footprints on the Heavens) (1997) the narrator, a contemporary of ours, tells the story of his grandparents, their children and friends who built Reykjavík in the beginning of the twentieth century. The story begins with a picture from the grandmother's childhood where she witnesses the transport of poor people from the country during the nineteenth century but ends sometime in the fifth decade of the twentieth century when she retrieves her son Ragnar from the Spanish civil war relatively unharmed. While Fótspor á himnum is a family saga it is Guðmundsson's intention to tell the story of a nation which half-unconsciously entered a new century, a new and a foreign world. This is the story of the transport from the country to the city but it opposes the simplistic picture depicted in the works of earlier authors.

Something about this story makes it very Icelandic. Perhaps just the cape mentality which the rich and strange collection of characters reflects. Or the reference to the character descriptions and modes of narration of the Icelandic Sagas. The narration is concise, the setting is simple, things are kept straight to the point. The parataxis is dominant and the sentences are short and simple. About a certain Signý at Oddstaðir it says for example: "She travelled alone and never said more than she had to." Wording such as this is also typical: "His mother Ingibjörg cried but his brothers said little." Or: "Many were then hurt on both sides." Words are not spent on things that do not matter, things that are not considered special enough and big enough: "With age people change into historians and clear away incidents like worms in a fish," the narrator tells us. It is the events that matter, the witty remarks at crucial moments, the everyday is not dwelt on, the little things. This is a story of big events, sometimes like the mentioning of chief things with poetic middle sections. Occasionally the epic progress (continuum) is breached, the narration becomes a kind of a staccato which reminds you of Fridrik Thor Fridriksson's movies Guðmundsson has written the scripts for and which are characterised by this same narratorial mode in the editing, that is Börn náttúrunnar (Children of Nature), Bíódagar (Movie Days) and Englar alheimsins (Angels of the Universe). The narrator's position is however different from that of the Icelandic Sagas. He does not hide behind the subject matter here but is constantly present, informs us for example about the kind of story he is telling and states his sources or the lack of them. His insertions are numerous. He quite often uses the story as a basis of interpretation and it is obvious where his sympathies lie: "... but these were only the fancies of undernourished boys who were driven on severely, but were never called anything but good-for-nothing and sloppy, constantly reminded of from where they came and who they were."

V

As can be seen from this compilation it is easy to find coherence in Guðmundsson's work. A few themes appear repeatedly in his works, such as the city and radicalism but the underlying thought is the breaking up, a deconstruction of the accepted, a confusion of the dominant. In Guðmundsson latest collection of poetry, Í auga óreiðunnar (In the Eye of Disorder) (1995), the dominant seems to be a confusion (or in confusion). This book is a kind of reckoning with the present and the past we inevitably carry with us. The fall of the wall has caused chaos and people hardly know where they stand: "The world rambles alone in the halls/and gets lost between floors." (10) A decade or so ago scholars found themselves in a kind of a problem of definition in relation to works by Guðmundsson and other authors of his generation. Some believed that the story or the Icelandic narrative tradition was reborn in his work. Some believed that the story had never vanished from the writings of Icelandic narration and saw a re-evaluation in the postmodernism of Guðmundsson's work. (11)

As I have pointed out Guðmundsson's work, and in particular the stories, has been characterised by a search, a search for a mode of narration, point of view, words, meaning. This search describes the postmodern state Guðmundsson has been, to a certain extent, connected with here. It is possible to say that a lack of direction is a distinctive feature of this state. It can also be said that we are situated in the interval period, on the boundary where traditional opposites and traditional forms are dissolved. Even though I am not asserting anything here, and assertions are hazardous in times like these,it seems as if some such definition fits nicely with Guðmundsson's work.

(1) Launsynir Orðanna, Bjartur, Reykjavík 1998.

(2) "Hin raunsæja ímyndun", Tímarit Máls og menningar, 2, 1990 : 99.

(3) Jón Yngvi Jóhannsson, "Upphaf íslensks póstmódernisma. Um fyrstu ljóðabækur Einars Más Guðmundssonar", Kynlegir kvistir. Tíndir til heiðurs Dagnýju Kristjánsdóttur fimmtugri, Ed. by Soffía Auður Birgisdóttir. Reykjavík : Uglur og ormar, 1999. 125-142.

(4) Einar Már Guðmundsson: Ljóð, Mál og menning, Reykjavík 1996 : 127.

(5) Þröstur Helgason, "Vitið í óvitinu. Um Engla alheimsins eftir Einar Má Guðmundsson", Andvari 1995, s. 86-88; einnig Guðna Elísson, ""Heimurinn sem krónísk ranghugmynd" Átök undurs og raunsæis í verkum Einars Más Guðmundssonar", Skírnir 171 (spring 1997) : 66-167.

(6) Einar Már Gudmundsson. Angels of the Universe. Transl. by Bernard Scudder. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995.

(7) For a further discussion of the dual narrator see Elenore M. Gudmundsson, "Á leiðinni út úr heiminum til að komast inn í hann aftur. Hinn tvöfaldi sögumaður í Englum alheimsins," Skírnir 171 (spring 1997) : 79-91.

(8) Gudni Elísson, see above. 190-196.

(9) Þröstur Helgason, see above. 86-92.

(10) Einar Már Guðmundsson: Í auga óreiðunnar, Mál og menning, Reykjavík 1995.

(11) See Halldór Guðmundsson, "Sagan Blífur. Sitthvað um frásagnarbókmenntir síðustu ára", Tímarit Máls og menningar, 3, 1991: 49-56; Gísli Sigurðsson, "Frá formi til frásagnar. Munnmenntir, bókmenntasaga og íslenskur sagnaskáldskapur 1980-1990", Tímarit Máls og menningar, 1, 1992 : 69-78; Ástráður Eysteinsson, "Um formgerð og frásögn. Önnur sýn á skáldsagnagerð síðasta áratugar", Tímarit Máls og menningar, 2, 1992 : 39-45.

Þröstur Helgason, 2000

Translated by Jóhann Thorarensen

Þorgeir Tryggvason:

As He Is

– On the Works of Einar Már Guðmundsson Since the Turn of the Century

I will tell the story in broad strokes and skip any bollocks about the morning sun rising and the rain drumming on roofs and all that annoying rubbish they have in books.

I won’t be tracing any lineages either, or causing a stink over problems from ages ago.

I’ll just say, like the soldier in The Tinderbox: Nothing can happen until I show up.

(The Beatles Manifesto 9)

Einar Már Guðmundsson makes no bones about the importance of the interplay between author, narrator and subject matter in his books. It seems he gives a lot of thought to this relationship on his own behalf, but also wants to open it up to his readers so they can participate in contemplating the rules of this game they are invited to play.

Since Angels of the Universe (Englar alheimsins 1987), Einar’s prose works have, either subtly or overtly, been based on “historical” material, be it (often very loosely) on his own family history, his memories or (in later years) written records of the distant past. The author himself appears as a character in Bars of the Mind (Rimlar hugans 2007), and many of the stories in Maybe the Mailman is Hungry (Kannski er pósturinn svangur 2001) seem to be direct documentation of real events in his life, although we also meet characters there who likely don’t exist outside of his books. Much of what Einar Már’s narrators have to say about their message and methods seems no less true for the man who pens them.

This is all done openly as part of the work and sometimes gives the text philosophical overtones. It makes readers aware of their participation in the act of creation rather than them being a passive audience in the firm grip of an irresistible narrator.

In the Literature Web overview of Einar Már’s writing since the turn of the century, Þröstur Helgason writes that his prose works have been “characterized by searching, a search for a narrative mode, a point of view, words, meaning.” Agreeing with this, we might ask if we will, in the next few decades, see the results of this search. Einar’s novels all take a very similar form in terms of content structure and, largely, of narrative mode and style. It is therefore intriguing to see how his approach produces different results depending on the nature of his subject matter. It is also always clear that the author shares the readers’ curiosity in this regard.

The History of the Fish Family

Where Þröstur’s article leaves off, Footprints in Heaven (Fótspor á himnum 1997) was Einar’s newest published work. In the following years, he published two more books, Dreams on Earth (Draumar á jörðu 2000) and Nameless Roads (Nafnlausir vegir 2002), which, together with Footprints, form a series. The books could even be said to constitute one long novel, a ca. 650-page family saga spanning the lives of more than three generations in the tumultuous twentieth century, from the interwar period to the postwar years. The series is loosely linked with Angels of the Universe as its narrator is Rabbi, the son of a taxi driver, who can be read as the brother of Páll, the main character and narrator of Angels, although there is little other connection in terms of content. The relationship is perhaps not dissimilar to that between The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, although Einar Már and Tolkien are otherwise very different authors.

Although its tendrils reach into the past and we are shown a glimpse of the next generation, the series is first and foremost the story of married couple Guðný and Ólafur and their children. They have ten children, eight sons and two daughters, who share the narrator’s attention, albeit in unequal measure. Aside from them, a great number of minor characters are introduced and their introduction more often than not includes the names of their parents, spouses and friends, which lends the narrative the air of an ancient Icelandic saga.

Aside from these associations, the series could be considered a modern and “urbanized” variant on the theme of the decline of rural life and the end of innocence due to migration and displacement.

This variation is especially apparent in the unexpected twist that due to conditions in Guðný and Ólafur’s home, not least his alcohol abuse, the children are sent to live on various farms on the South Coast. They each experience very different treatment, which shapes their characters to a large degree. An unscrupulous clergyman enslaves the towering Ragnar and neglects to teach him to read, while poor but kind farmers take in his sister Sigrún and succeed with their gentleness in curing her of homesickness.

This is a fateful story from the point of view of its characters even though members of “the fish family”, as Guðný calls her descendants, come from society’s lowest strata and are not all successful in working their way up. Ragnar, who could be considered the main character of the first volume, becomes a dedicated communist and goes to Spain with his best friend to aid in the fight against fascism.

The second volume centralizes the fate of Sigrún, who has tuberculosis, and the personal history of Ólafur, the narrator’s father. In Nameless Roads, a large role is played by Helga, an activist, shanty-dweller and the mother of Ragnar’s child, and by Ívar, a wealthy naturopath. The third generation also becomes more visible.

None the less, familiar subject matters continue to crop up. The loose narrative style of the series creates a feeling of witnessing the recall of a communal fund of memories and stories. One story calls for another being brought up and told as a parallel or a contrast, regardless of whether it has already been recounted. The narrator and his sources speculate on the characters’ personalities based on their reputation, and contemplate the logic of decisions made and the workings of fate. This makes the series a fragmentary panorama of the life of a big family in the larger context of the social changes and turmoil of the twentieth century, rather than a dramatic saga which leads from one event to the next, towards some kind of result or resolution.

To begin with, occasional chapters are staged as Rabbi’s interviews with his relatives, or as him remembering conversations about the past which he has witnessed. Slowly, Rabbi’s voice is established as that of an omniscient narrator but without sacrificing the looseness and circularity which are basic characteristics of the work.

Home Turf

“It won’t be a trilogy because the series isn’t finished,” said Einar Már in an interview on the publication of Nameless Roads. This has not exactly come to pass but almost all of his works are, in fact, linked by hidden paths and passageways. Characters flit between them and whole villages are created as settings for scenes in different time periods, and even sneak into narratives which must otherwise be considered completely factual.

However, it is the narrative approach which most binds the oeuvre together. The chaotic and repetitious narrator who interprets and contemplates the material as he goes along continues to reign over the later books, whether it is Rabbi or someone else who has the floor. Or even Rabbi by another name.

This is apparent in the next novel after the trilogy. There, Einar returns to another of his previous narrative worlds and revives a familiar narrator, Jóhann Pétursson from Knights of the Spiral Staircase (Riddarar hringstigans 1982).

A ghost roams the streets of the world, the ghost of the Beatles.

It feels like the universe is bracing for a mad drum solo.

(The Beatles Manifesto 7)

Although the music of the era echoes throughout this story of the teen years, conflicts and maturity, The Beatles Manifesto (Bítlaávarpið 2004) hardly lives up to its name. If only because the arch nemesis, The Rolling Stones, really take up more space in the text, as well as lesser heroes.

In terms of content, The Beatles Manifesto is mostly a typical young adult novel and a logical sequel to the childhood tales in Knights. It is full of pranks, rivalry between neighborhoods, romances, shoplifting and clashes with school authorities or parents who have their own problems and can’t quite handle a soul as knowing and restless as Jóhann Pétursson, who cannot find a place for himself in family life or under the thumb of principal Herbert with his “liberal” school policies.

It is the meditative yet observant narrative voice which elevates The Beatles Manifesto above the predictable and threadbare material:

We had no rules but the school rules, and no way were we obeying those. They didn’t say anything worthwhile, anyway, only what was and wasn’t allowed and of course nothing was allowed. (53)

The measured yet bewildered and wide-eyed innocence of Jóhann’s character troubles his parents and teachers but fascinates readers. These qualities enable him to narrate the tragic end of the story without sentimentality. His mother has possibly passed on and the beloved Helga next door has moved away. As in so many of Einar Már’s narratives, the story runs down leaving the reader with a feeling that it is not finished, although Jóhann has yet to speak up again.

Bars of the Mind (Rimlar hugans 2007), on the other hand, has a clear and decisive ending. Or, more accurately, the story ends where it began, with Einar Þór and Eva declaring their trust the author, Einar Már, to tell their story and speak on their behalf.

You are reading Bars of the Mind – A Love story, the latest novel by Einar Már Guðmundsson. As with all my novels, I find my material in reality. I base my stories on events. (Bars of the Mind 157)

Bars of the Mind may, as Einar Már asserts here, demonstrate the same attitude towards the interplay of fiction and reality as his other books but it is otherwise rather unique among his works from this period. It is the only work in which more than one voice speaks, and in which one of the speakers is female.

The story is composed of different narrative threads. On the one hand, Einar Már describes his own struggles with alcoholism, his healing process under the guidance of SÁÁ, and his personal experience of the principles of the AA-organization. On the other hand, we follow the correspondence of two addicts, Einar Þór and Eva. Einar Már met Einar Þór through his struggle with addiction and when the story is set, the latter is imprisoned at Litla Hraun penitentiary on drug related charges and awaiting sentencing. In their letters, Einar Þór and Eva remember their past but also cultivate and strengthen their relationship, and prepare for the future.

Although many aspects of Bars of the Mind have strong non-fiction overtones, Einar Þór is a familiar Einar Már-character, not dissimilar to Jóhann Pétursson as he appears in The Beatles Manifesto. He is something of an outsider but not dumb despite having a hard time in school. He is peculiar but is rewarded for that with the role of the clown, first at school and then nationally with a role in a film and an appearance in Stundin okkar children’s TV program. Later, Einar Þór becomes a convincing punk, resentful of society and his family, and, for a while, a prominent drug dealer.

Eva has also struggled with substance abuse since her teens but the reader feels strongly that there are better times ahead, both for the two of them and for Eva’s children, to whom Einar Þór is a father figure. The tone of the love letters is tender, genuine and deeply sincere, and the author’s compassion with his characters is strong and contagious.

There are clear intertextual links between Bars of the Mind and Einar’s collection of poetry, A Shortcut Past Death (Ég stytti mér leið framhjá dauðanum 2006). Addiction and recovery are among the main themes of the collection and it contains the poem “A Love Star over Litla Hraun”, which appears in the novel. The collection is linked to other works by Einar Már; “Oslo Police Station, Summer 1978” describes an event which resurfaces in Passport Photos a few years later. Nostalgic retrospection crops up throughout the collection and it also contains lofty but sincere love poems reminiscent of both the tone of the letters between Einar Þór and Eva in Bars of the Mind, and of the love affair that begins and grows in Passport Photos:

I remember the day

you were beautiful as the sun,

hot and clear as ember,

walked with me on sunbaked streets,

radiant...

(“The Joy of Mourning”)

The collection also contains experimentation with rhyme, alliteration and repetition reminiscent of the chorus in song lyrics, not least in a powerful poem, “Theology for Teens”, which repeats “all is so old in the fridge, nothing new under the sun”:

There was love, pastries

and laughter,

but now I hear nothing

but bluesy buildings

blathering cliques

and the shrieks leaking from the pipes...

Yes, all is so old in the fridge

nothing new under the sun.

Einar Már’s latest collection of poetry, To Whom it May Concern (Til þeirra sem málið varðar), came out in 2019 and is a more understated work. Exuberance and fervor give way to pensiveness, tranquility and a doubt perhaps reminiscent of the narrators of the novels with their constant contemplation and cautious questioning of what is truly concrete when it comes to history, fact, memory and reality:

Now I stand on the hill

and look at the sky.

The sky looks back.

Of course, I can’t prove it

but I see no reason to doubt

my own word.

The sky is in its proper place

and I suppose I am too.

(XX)

Tangavík and environs

I always end up digressing, somehow, but that’s what stories are like, they happen mostly outside themselves. Whenever you are describing one thing, you’re really describing some other thing. (Bars of the Mind 217)

Einar Már participated actively in the reckoning after the banking collapse with articles and speeches. Two collections of his articles, The White Book (Hvíta bókin 2009) and Number Zero Bank Street (Bankastræti núll 2011), contain his reactions and reflections on the causes, culprits and impact of the crash and all the injustice and corruption it suddenly revealed or which, perhaps, suddenly became an acceptable subject matter.

These texts are very heated and direct, and perhaps more important as a meaningful testimony of the nation’s state of mind in turbulent times, than as an incisive analysis or a reliable record of the course of events, causes and consequences. And, as he is wont to do, Einar Már links his own unique narrative world to contemporary issues:

Sveinn and Guðríður were dirt poor when they arrived in Tangavík. They had been forced to leave all personal effects and clothing behind. In an application for a subsidy for them, the parson writes that they have borrowed one old cow. He went to sea but the catch was small. The poison from the eruption site damaged the fishing grounds. One fishing season after another was a disappointment. (Number Zero Bank Street 120)

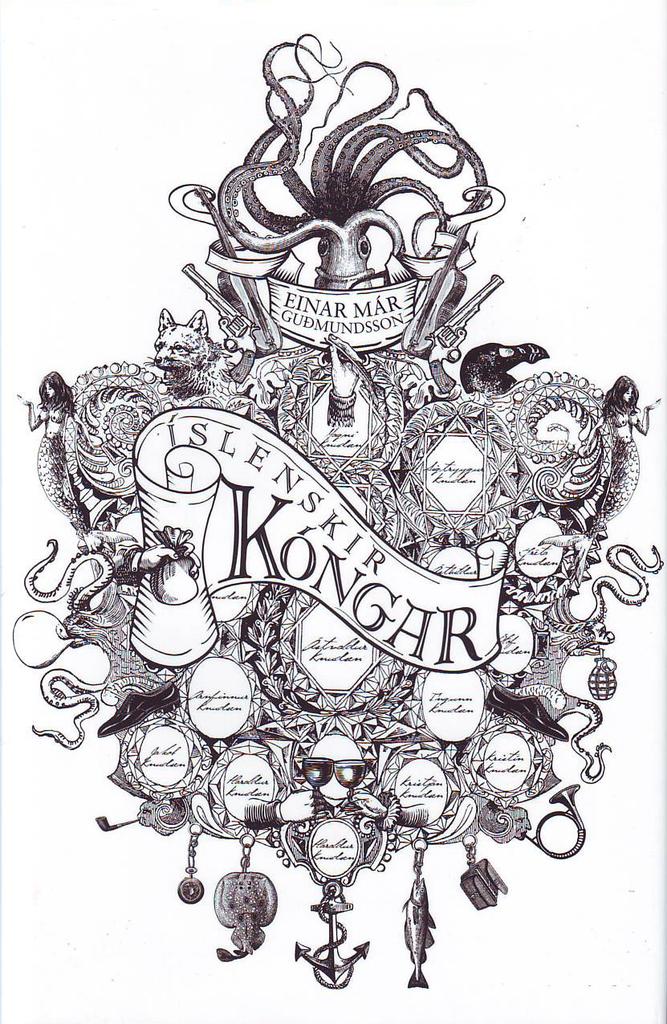

Einar Már would return to the material glimpsed here in 2021. His next novel, Kings of Iceland (Íslenskir kóngar 2012), is set in Tangavík like this micro story of Sveinn and Guðríður, albeit in a different time period.

Kings of Iceland could be called a post-crash novel, an attempt to examine the origin of the Icelandic tycoon and the support he has in the worlds of business and politics. To this purpose, Einar creates Tangavík, a village on the South Coast of Iceland. In Kings of Iceland, it becomes a kind of archetypal Icelandic fishing village, brimful of colorful characters from all walks of life who are more or less interrelated and almost all connected to the family that rules the town, the Knudsens.

It said a lot about Tangavík, and the position of Tangavík that nowhere in the country was the Nazi party as strong, and nowhere in the country were there more communists.

Nowhere in the country were more ships lost and nowhere in the country was there more dancing. Nowhere in the country was there more weeping and nowhere in the country was there more laughing. Nowhere in the country was there more grief and nowhere in the country was there more joy. (Kings of Iceland 108)

Tangavík is an archetypal Icelandic village and the Knudsens resemble other great Icelandic families. We have the head of the family, Ástvaldur, who fights his way to riches with industriousness, brazenness and luck; all kinds of artistic black sheep and strange tricksters; and, finally, a modern offspring who wrecks everything:

They say that Ástvaldur Knudsen would turn in his grave if he could see the state of Tangavík in Jónatan Knudsen’s hands, because Jónatan and his cohort have sold all of Tangavík’s assets, emptied savings banks, mortgaged property and wasted it on pet projects, then tried to keep the whole thing going with slide shows. (Kings of Iceland 29)

Kings of Iceland displays great narrative and creative glee which the author makes no serious attempts to contain. So far as it is an investigation into the root causes of the crash, it is so mostly because “[w]henever you are describing one thing, you’re really describing some other thing”, as we learn in Bars of the Mind. The narrative is unrestrained and full of digression and adventure and, the dead move easily in and out of the narrative reality:

Ástvaldur scraped the snow out of the rock with his mitten. The cold gripped his hands, his face got scratched and his strength ran out. He was hanging by his fingertips and could barely find footing. Then he passed out. Then came his grandmother, Jakobína, who had twelve children, eight boys and four girls. She had died two years before and took his hand and led him up the part of the cliff face that no one had climbed before. (Kings of Iceland 25)

This interplay between the living and the dead, a narrative technique borrowed from magical realism, becomes even more prominent in Einar’s latest novel, which is also set mainly in Tangavík and names one of the Knudsens as a key source of information.

It can be argued that Poetic Criminology (Skáldleg afbrotafræði 2021) is no less deserving of the label of post-crash novel than Kings of Iceland. It is set during “Iceland’s epoch of crime” at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Society is in upheaval following the famine of the mists, the tenets of the Enlightenment have resulted in more moderate criminal punishments and the echoes of the French revolution carry all the way to Iceland. This all contributes towards undermining governmental authority and empowering the public, not least its less savory elements:

These criminals, many of them well known, famous on their home turf and beyond, these primitive rebels or whatever you want to call them, are sometimes called the originators of organized social movements and the struggle for justice but they are also said to be akin to contemporary street gangs, criminal organizations and anarchists. This can easily all be true as so many things are paradoxical in history and in life. (Poetic Criminology 42)

The points of contact between Tangavík and the real world are clarified in Poetic Criminology. This is mainly achieved via the main narrative thread of the book, its inciting incident, which is the background and build-up to a raid on a rich farm in the area, called Holt in the book, quite obviously based on the famous raid on Kambur-farm. Also, one of the book’s main characters, Sigrún Karlsdóttir, nicknamed “Sigga the sea dog”, is modeled on “skipper” Þuríður Einarsdóttir. This links Tangavík clearly, and almost certainly on purpose, to Eyrarbakki, although Einar Már avoids committing too firmly to historical facts and real, historical characters.

A great number of characters, both the raiders and other villagers, are introduced in the story. Central characters are Óli the blind, an unpopular laborer unwelcome on all the local fishing boats, and Jóna, a pauper who is placed with Óli as a servant and whom he sexually abuses. Óli becomes one of the main instigators of an attack on Holt to rob farmer Egill, and Poetic Criminology ends as the idea is moving into the stages of planning and action. A sequel is announced.

In fact, there are many stories of the raid and connected events which might supply the material for a second volume. Einar Már’s narrative mode in Poetic Criminology is in many ways reminiscent of the trilogy of 1997-2002. The narrator does not attempt to conceal what will happen later in the story, which explains and justifies his describing whatever catches his fancy, naming his sources and contemplating the meaning and context of the events he describes. Although this is the story of a famous criminal case, the treatment of the material is almost completely opposite to the traditions of the crime genre, where readers must never suspect what will happen next.

Poetic Criminology may be said to bridge the gap between Einar’s wider narrative world and his historical novel, Dog Days (Hundadagar 2015). In it, we also find ourselves mostly on the South Coast, and also examining historical events at the turn of the nineteenth century. However, Dog Days is in many other ways unique in Einar Már Guðmundsson’s oeuvre.

Although the narrator is similar to those of his other novels – meditative, somewhat childish, and unconcerned with describing events in chronological order or clarifying the logic of the narrative development – Einar Már is mostly guided by historical documentation here, much more so than in Poetic Criminology.

Dog Days is a novelization of the biographies of several historical figures, mostly the reverend Jón Steingrímsson or “the fire parson” (1728-1791) and Jørgen Jørgensen, the “dog days king” (1780-1841), but also Finnur Magnússon, confidential archivist (1781-1847), and Guðrún Johnsen, the “dog days queen” (1789-18??).

The first two characters are explicitly centered and for a while it seems that Einar Már must intend to model his book on Parallel Lives by Greco-Roman historian Plutarch, in which he compares and contrasts great figures from Greek and Roman history in terms of their accomplishments, character and moral fiber.

There don’t prove to be all that many interesting similarities between the devout but quick-tempered priest and the globetrotting, audacious, wild and deeply flawed Danish son of a watchmaker. However, both biographies are conscientiously related.

It is undeniable that Einar has a better grasp on Jörundur’s eventful and extraordinary life than on the fire parson’s daily struggles and he is aware of this himself, dwelling much more on the former. There is no great gulf between Jörundur’s adventures around the world, and especially in Iceland, and the unruliest characters Einar himself created earlier in his career:

It is clear from descriptions of Jörgen Jörgensen’s childhood that he was what is nowadays called hyperactive. He could not settle down to study even though he had good learning abilities, very good, in fact. Now, he would be put on ritalin or some sedative, just like many more of our protagonists and many who have left their mark on the world. (Dog Days 55)

In between these two historical novels, Einar Már published another book which may be read as a link between different spheres within his oeuvre. According to the cover blurb on Passport Photos (Passamyndir 2017), it belongs to the narrative world of the trilogy and Angels of the Universe, and this link is clear. The narrator could be the same character; he has a brother named Páll who is “kind of like Syd Barrett” (20) and who “paints, writes and plays drums. He is clever but he is often difficult.” (21)

Unlike these books, however, the narrator of Passport Photos is unquestionably its main character. He is called Haraldur (not Rabbi), a young aspiring writer with romantic dreams of roaming Europe which he intends to make reality in the company of some friends and acquaintances, starting with casual work in Norway, the home of his idol, Knud Hamsun, and continuing with a carefree southward ramble, maybe even all the way to Sicily, the setting of The Great Weaver from Kashmir. This works out for the most part but, in an unexpected twist, Haraldur falls in love early in the story and must adjust all his plans to this new situation.

Although Passport Photos is written in the form of a novel, it seems it must be based on personal recollections. Some supporting characters are reasonably recognizable as real people, the most obvious being the filmmaker and activist Rúna, whom the narrator visits in Rome and who can hardly be anyone but Róska.

Readers will also notice a scene in an Oslo police station where the two friends Haraldur and Jonni go to get work permits and witness the hostile treatment of a Pakistani who is there for the same purpose. As has already been mentioned, the same incident is the subject matter of a poem in A Shortcut Past Death, where it clearly appears as a memory.

It seems that Haraldur is aware of what kind of author Einar Már would later become:

I go to describe one event, something that happened, but right away, I’m talking about something else, that’s how I tell stories. I know where I want to go but I don’t know how to get there. (Passport Photos 23)

When I start to describe something, I think of something else. I would really like to say much more and tell many more stories than I do but then there wouldn’t be room for the story I’m telling and it would drown in other stories. (55)

[...] after all, I considered myself a disciple of poets who just talked to themselves, or to no one or the breeze, but still said a lot about the world. But I knew that I would write stories. (192)

Although Passport Photos has an air of non-fiction, there are also pathways leading from it to the more “imaginative” parts of Einar Már’s oeuvre. Haraldur and Jonni are students of Arnfinnur Knudsen, the teacher who inspired the book about his family and its grip on Tangavík, Kings of Iceland, and the two friends have even contrived to work a fishing season in the fictional village. At one point we also encounter the mysterious doctor Róbert who also appears in some stories in Maybe the Mailman is Hungry.

The narrative world which Einar Már has constructed within his large oeuvre proves to be impressively complete, full of wonder but also an incisive study of the real world. Aside from the various intersections and all the secret passages between Tangavík, Eyrarbakki, the Holt-neighborhood, the Vogar-area, Tasmania and Taormina, it is the narrator’s approach, the author’s vision, that binds it all together with loose but surprisingly sturdy bonds.

You must forgive me but I’m thinking so many things, so I start telling all kinds of stories, all kinds of weird stories. (Passport Photos 23)

Þorgeir Tryggvason, mars 2022

Translated by Eva Dagbjört Óladóttir

Articles

Articles

Allard, Joseph C. "Einar Már Guðmundsson."

Icelandic Writers (Dictionary of Literary Biography). Ed. Patrick J. Stevens. Detroit: Gale, 2004. 48-54.

See also: Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, 492-93 and 459.

Reviews of specific works

Draumar á jörðu (Dreams on Earth)

Hallmundsson, Hallberg. "Draumar á jörðu: Skáldsaga (Dreams on Earth)."

World Literature Today 76.1 (2002): 196.

Fótspor á himnum (Footprints in Heaven)

_____. "Fótspor á himnum (Footprints in Heaven)."

World Literature Today 72.4 (1998).

Englar alheimsins (Angels of the Universe)

Steinberg, Sybil S., and Jeff Zaleski. "Forecasts: Fiction." Rev. of "Angels of the Universe".

Publishers Weekly 244.3 (1997): 392.

Hvíta bókin (The White Book)

Wivel, Henrik: "Landsforræderi: en hvidbok af Einar Már Guðmundsson"

Nordisk tidskrift för vetenskap, konst och industri 2010, vol. 86, #1, pp. 77-80.

Kannski er pósturinn svangur (Perhaps the Mailman is Hungry)

Wolf, Kirsten. "Kannski er pósturinn svangur (Perhaps the mailman is hungry)."

World Literature Today 76.3/4 (2002): 132.

Excerpts from articles and reviews

[...] Fótspor á himnum (Footprints in Heaven) is a family saga covering three generations, and as such it does not easily lend itself to plot summary. It begins with the narrator''''s great-grandfather sometime in the latter part of the nineteenth century and continues-in the snippets of dialogue the narrator has with his aunts and uncles-up to the present, although the actual events described end somewhere around the beginning of World War II. Most of the story concerns the grandparents and their offspring. Oli the Inspector (of fish), as the grandfather is called, starts fishing with his father as a preteen boy, and he knows all there is to know about fish-and the sea. Even after he has become blind, he can describe the form of the waves by the mere sound of the weather. But he succumbs to alcoholism, and the family, which he and his wife can no longer support, is broken up. The children are sent away to various farms in the country, where they stay for different lengths of time, some fairly content, some mistreated. Ragnar, the most robust and rebellious of them, repeatedly runs away. All finally return to Reykjavik. Ragnar becomes a day laborer and self-appointed labor agitator and joins the Communist Party. By then, his father, Oli the Inspector, has died of tuberculosis. During the Spanish Civil War, Ragnar goes to Spain, along with an even more adventurous friend of his, to fight against Franco. Both manage to survive a year or two at the front, but Ragnar is wounded, losing a finger. His friend loses his wife. As he had left for Spain, he had told her: "There''''s a man in Spain called Franco. I intend to shoot him, Then I''''ll return and love you as before." Alas, she has grown tired of his comings and goings; when he returns, she has taken up with another man.

In some ways, Fótspor á himnum is reminiscent of the old Icelandic sagas, both in style and substance. The narration is direct, the sentences short and often terse, and there is little dedication to minutiae. It is, however, a definitely modern saga, whose episodic structure recalls the movies: it is divided into twenty-seven chapters, each of them in two to four subsections, the narrative going back and forth in time. This works quite well and the story flows smoothly, for the telling is deft and engrossing. And though the novel is mainly a tale of just one family, it reflects to a certain degree the history of Icelandic society during the time period the book spans. It is a period of tremendous changes, as Iceland practically steps out of medieval times into the modern era. The historical events and trends, however, are always sketched in with broad, sweeping strokes, serving mostly as backdrop for the large gallery of characters.[...]

(Hallmundsson, Hallberg. "Fótspor á himnum")

-------------------

[...] In some ways, Draumar á jörðu is as accomplished as Fótspor á himnum. Its structure is the same, even down to the number of chapters (twenty-seven), each of them in two to five subsections, and the narrative goes back and forth in time as before, and from one character to another. Neither has the author lost any of his storytelling charm: his lyricism and humor still stand him in good stead as he deals with human misery and death. It is a well-written book.

And yet I felt a bit disappointed. It's not just that the new book offers more of the same, though that no doubt is part of my reflex; but these additional doses of the family history seem to be less potent, somehow thinned out. Or maybe the family members onstage here are just a bit less colorful than the previous ones. I have to admit, too, that I felt the prominence of tuberculosis in the book a bit tiresome, though that may not seem to be a very generous reaction. Of course, it is true that tuberculosis was a scourge in the first half of the last century, and I well remember the time when the "white death" was still often talked about. Some relatives of mine were affected also, though none in my immediate family. But I don''''t know if it ever became a central theme in any large family, as occurs in this book. Perhaps the author, who was born at about the time when tuberculosis was practically eradicated from Iceland, sees it through the magnifying glass of a too-narrow scrutiny. [...]

(Hallmundsson, Hallberg. "Draumar á jörðu: Skáldsaga", p. 196)

-------------------

Thirty-eight short stories are included in this volume, ranging in length from only seven lines of text to six pages. "Reykjavik" may be singled out here for translation due to its brevity, but also because it is representative of Einar Már Guðmundsson''''s wit and writing style: "The city is colorless but has a mystique about it that few understand except those who have lived here for a long time. However, they have grown together with the city to such an extent that they pay no attention to the mystique. ''''What do you think of Reykjavik as a city?'''' I ask my friend, who has traveled widely and knows many cities. ''''I know it so well that I stopped noticing it a long time ago,'''' he says."

The stories in Kannski er posturinn svangur vary greatly. Common to all of them, however, is that they are "slice of life" narratives that have as their protagonists known and established people as well as people on the margins of society. The overall picture that emerges from the book is an honest and insightful portrayal of everyday life in Reykjavik and social conditions in Iceland in general.

(Wolf, Kirsten. "Kannski er pósturinn svangur", p. 132)

Awards

2015 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Hundadagar (Dog Days)

2012 - The Swedish Academy's nordic literature prize

2010 - Carl Scharnberg's Memorial Fund

2002 - Icelandic National Service Writer´s Fund

2002 - The Knight´s Cross of the Icelandic Order of the Falcon

1999 - The Karen Blixen Award, an honorary award from the Danish Academy

1999 - Giuseppe Acerbi Literary Prize. In the town Castel Goffredo in Italy.

1995 - Nordic Council Literature Prize: Englar alheimsins (Angels of the Universe)

1994 - VISA Cultural Prize

1994 - DV Cultural Prize: Englar alheimsins (Angels of the Universe)

1988 - Bröste´s Optimism Award

1982 - First prize in a literary competition hosted by Almenna Bókafélagið Publishers: Riddarar hringstigans (The Knights of the Spiral Stairs)

Nominations

2007 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Rimlar hugans (Bars of the Mind)

2004 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Bítlaávarpið (The Beatle Manifesto)

2000 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Draumur á jörðu (Dreams on Earth)

1997 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Fótspor á himnum (Footprints on the Heavens)

1991 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Klettur í hafi (A Rock in the Ocean)

Því dæmist rétt vera (Rightly Judged)

Read moreÍ Tangavík ríða hættulegar hugmyndir húsum, hugmyndir um réttlæti og jöfnuð. Á laun ráðgera menn að losa hina ríku við auðinn sem íþyngir þeim en þegar látið er til skarar skríða er yfirvöldum ekki skemmt. Glæpir ógna gildum samfélagsins og mikið liggur við að bæla niður mótþróa og uppreisnarhug; finna hina seku, dæma hart og refsa grimmilega.. .

Islandske konger

Read more

Passamyndir (Passport Photos)

Read more

Hundadagar (Dog Days)

Read more

On the Point of Erupting: Selected Poems

Read more

Navnleysir vegir

Read more

Íslenskir kóngar (Kings of Iceland)

Read more

Bankastræti núll (A bankstreet number zero)

Read moreEt vous, vous continuez à écrire, non?

Read more