Bio

Eva Björg Ægisdóttir was born in Akranes on June 27, 1988. In 2013, she finished a Bachelor's degree in Sociology at the University of Iceland, together with a minor in Comparative Literature. After that she moved to Trondheim in Norway, where she completed a MSc degree in Globalisation.

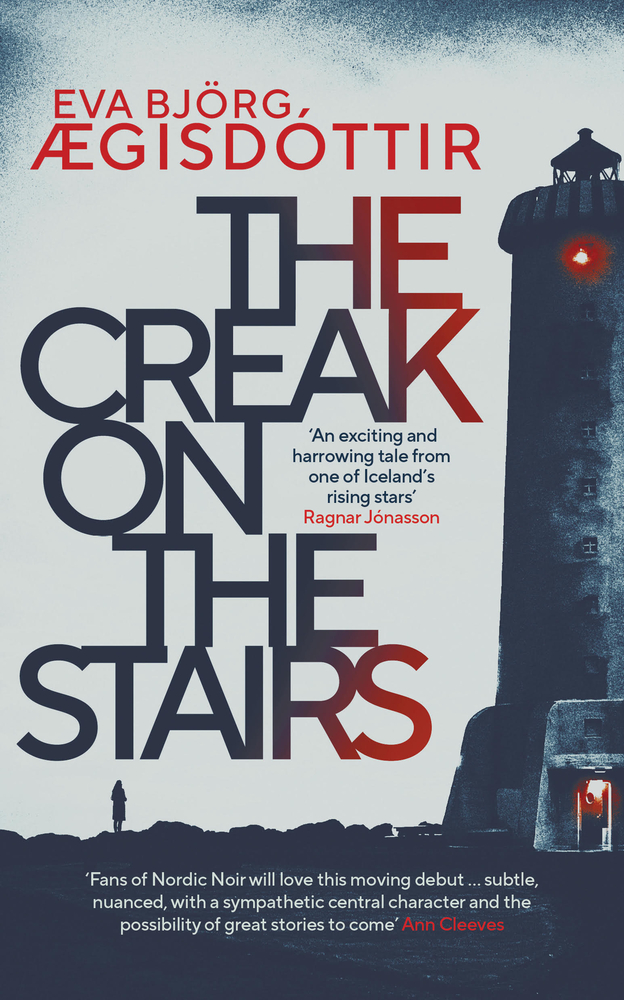

Her first introduction to writing was when she won award for a short story in her primary school, Grundaskóli, in Akranes. Nearly fifteen years later, in 2018, she published her first novel, Marrið í stiganum (The Creak on the Stairs), written after her studies in Trondheim, when working as a flight crew member. The novel was the first to receive Svartfuglinn (Blackbird Award), a crime writing price for a debut crime novel.

Since then Eva Björg has published a new crime novel annually and is now able to devote her time to writing. Her novels have garnered various awards in Iceland and abroad. Marrið í stiganum won the CWA Dagger and also the Thrillzone Award in Holland for a best debut.

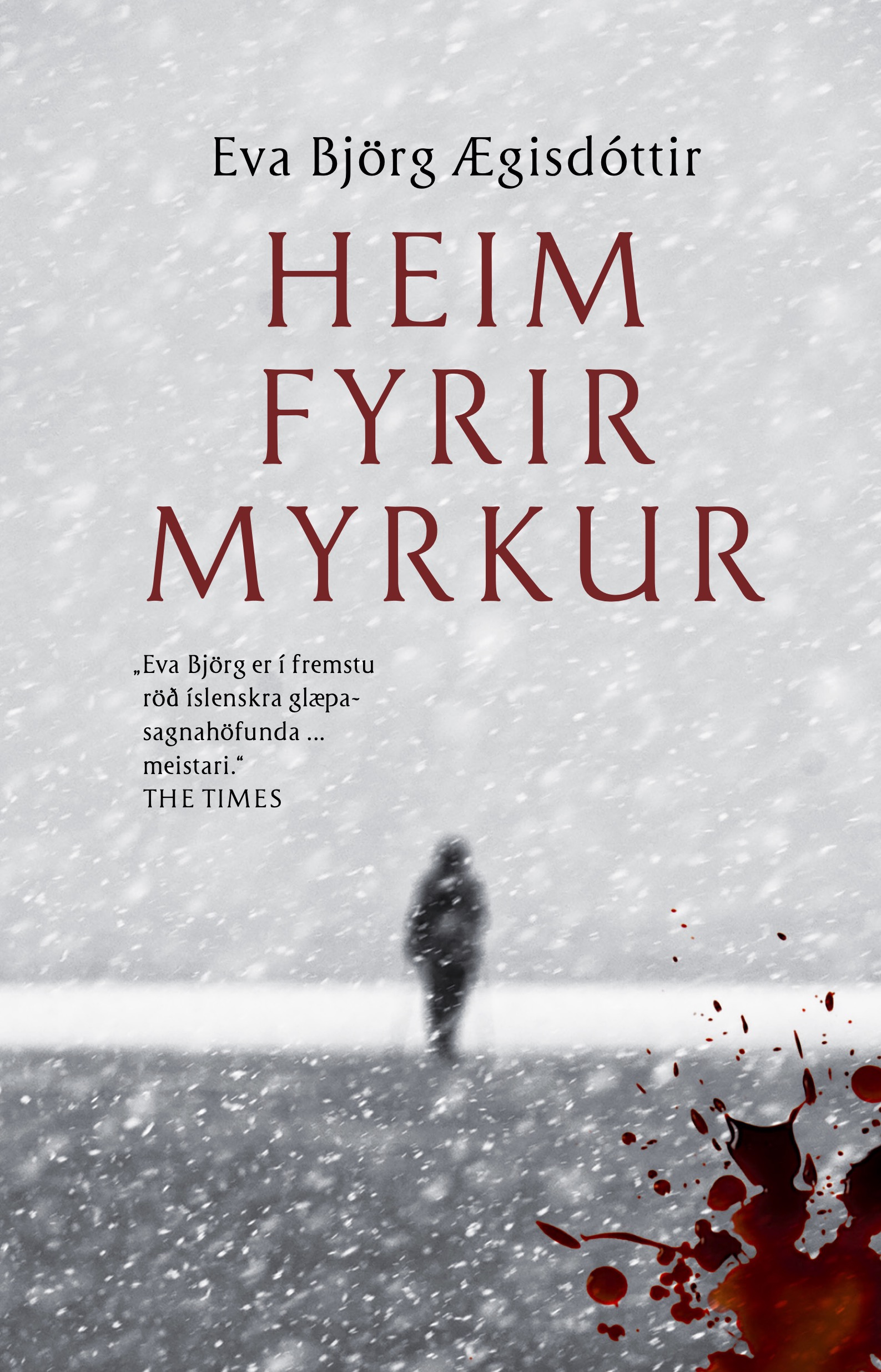

Heim fyrir myrkur (Home Before Dark) received the Icelandic crime writers award, Blóðdropinn (The Blood Drop) in 2023.

Eva's books have been translated into numerous languages and published in France, UK/USA/Canada/Australia Germany, Holland, Greece, Makedonia, Israel, Estonia, Japan, Poland, Spain, Portugal, Ethiopia, Bulgaria, Russia, Serbia, Hungary and Brazil.

About the author

Eve’s Unclean Children

In 2018, Eva Björg Ægisdóttir won the Svartfuglinn mystery writer’s award for her first book, The Creak on the Stairs. The novel also earned her the Blóðdropinn award and, in the UK, the Golden Dagger award for best newcomer. Since then, Eva Björg has published annually: Girls Who Lie 2019, Night Shadows 2020, You Can’t See Me 2021, Boys Who Hurt 2022, and Home Before Dark 2023. She won another Blóðdropinn award for Home Before Dark.

A Multifaceted Story of an Abused Child

The Creak on the Stairs is a typical first novel in a series. It begins with Elma Jónsdóttir accepting a position with the Akranes police, allowing the reader to get to know the workplace as she does. We also get to know Elma’s police colleagues: Superintendent Hörður, Sævar, and Begga. Excepting Hörður, who is in his fifties, these are people in their early thirties. Elma grew up in Akranes but left in her late teens, so this is a return to her childhood home. Her parents and sister still live in the town.

The narrative is in the third person, and the point of view is not only Elma’s but shifts between a few key characters. The author immediately starts to introduce characters connected with the crime, although the crime itself is not mentioned until the body is found on page 62. Among others, we meet Hendrik and Ása, local magnates who own rental properties and a business, and have somewhat inflated egos. Their son and daughter in law, Bjarni and Magnea, are wealthy, beautiful, and stylish, and the reader is given a glimpse into their life. Why? Well, they must have a skeleton in the closet.

The narrative is interspersed with short chapters set in Akranes in 1989, in which a neglected and abused child tells their story. This will become a characteristic of the series. The reader has a clearer understanding of events than Elma and her colleagues, as the story is told from multiple points of view, and the reader sees into both the past and the mind of whichever character the point of view is with each time.

The story also takes us to Reykjavík, where friends and family of Elísabet Hölludóttir, a pilot in her thirties, are notified that her body has been discovered by the old Akranes lighthouse. She has been hit by a car and dumped in the ocean.

How is Elísabet connected to the fat cats of Akranes, and how is the child’s story, set nearly thirty years earlier, connected to the crime?

The police investigation in The Creak on the Stairs proceeds quite conventionally. Elma and her colleagues go door to door conducting interviews as the clues mount up. The old lady next door, classmates, teachers, and janitors. People are asked about the past, information is collected, and sometimes the investigators catch a break. This is a familiar approach for the police to take, slow and steady.

Scandinavian Social Ills

The four novels which center detective Elma Jónsdóttir belong to the Nordic Noir or Scandi-Noir genre. The narrative details not only the investigation, but also the private lives of those conducting it. We are introduced to three police officers, Sævar, Hörður, and Elma, their past and immediate family, and we observe their work and daily lives.

This genre of crime fiction, named after the Nordic countries or Scandinavia, addresses various social problems. The stories contradict the myth that Scandinavia is a welfare paradise where everyone is happy, rich, and cheerful. The main character is usually a detective; two of the better known are the Swedish Kurt Wallander from Henning Mankell’s books, and Erlendur Sveinsson, written by Arnaldur Indriðason. Harsh environments, dry wit, terrible crimes — and the text is not overly burdened with metaphors, ornamentation, or ostentation. The detective’s private life is often in shambles but, having a strong sense of justice and a unique talent for solving complex crimes, they live for their work. Detective Elma is a departure from the archetype in this, as will be discussed below.

Eva Björg discusses various social problems, but steers clear of organized crime, a favorite topic among many of her colleagues in the Nordic countries. Using a small community like Akranes as a setting is convenient in many ways, as bullying and shunning are among Eva Björg’s favorite subjects, and appear in some form in each of her novels. Many people have been victims of unscrupulous small-town gossips, and in fact, detective Elma is among them.

Other issues Eva Björg often focuses on are neglect, violence, and sexual abuse against children, as well as economic inequality, rape, and domestic violence. She also addresses many issues which might be viewed as less serious but are still worth examining. For example, she often touches on the distorted images we see in social media — the difference between what people’s lives look like online, and their day-to-day reality. She also discusses infidelity, and questions surrounding responsibility and neglect in intimate relationships, as well as the pressures experienced by both men and women in contemporary society, albeit differently according to gender.

Black Elf Found in a Cave

It underlines the marketing of the Icelandic crime novel as a gift item that the stories all begin in November or December, and it is obviously assumed that they will be read over the Christmas holidays. Most of them are set in contemporary time, so the reader feels as if they are observing the investigation as it occurs. Snow, cold, and darkness also create an appropriately bleak atmosphere for an Icelandic crime scene.

Girls Who Lie begins in November. Elma, Sævar, and Hörður are called out to Mt Grábrók, where a body has been found in a lava cave about an hour’s drive from Akranes. It is clear from the beginning that the body belongs to Maríanna, a woman who disappeared from Borgarnes the spring before.

The author spends more time exploring the horror of the corpse than in the first book. It has been in the cave for so long that the children who find it think it is a mythical black elf. The coroner gets to describe the process of decomposition in detail:

“The parts that were less protected, like the hands and face, have mostly been reduced to the bare bones, though there are remnants of tendons and ligaments, since these are generally slower to decompose. The brain and eyes have completely vanished, of course, but the abdomen has retained considerably more flesh, as you can see.” (46)

This narrative is also interspersed with scenes from the past. These are narrated by an anonymous woman, and the chapter headings refer to the age of a child she gave birth to at the beginning of the story. Neither the woman nor the child is mentally stable.

The investigation progresses; it is comprehensive, and has many twists and turns. Accusations of sexual abuse — true or untrue — cause those involved to be shunned. The court of public opinion repeatedly takes matters into its own hands.

The victim was not a good mother in life as old trauma, poverty, and addiction impacted her ability as a parent. Questions surrounding the problem of child-neglect, and of what makes someone fit or unfit to raise a child, are ubiquitous in Eva Björg’s books, and a major theme in Girls Who Lie.

The Reader Knows More than the Police

All six narratives begin with a fragment of text which is intriguing but remains opaque until towards the end of the story. It is something unsettling — nameless people in distress or on some shady business. It is hard to reach any conclusion about it without doing just what the author wants and reading on. Readers of crime fiction are a tough crowd, and their curiosity must be piqued immediately, even before introducing characters, setting, or a crime.

As has been mentioned, Eva Björg sets all her stories in two different points in time, as do many of her Nordic colleagues. The narratives are intertwined; the investigation of a crime in the present creates a dialogue with a story from the past, and the connection between the two slowly becomes clear to the reader. A dialogue is created between the texts, and the answer to the mystery is revealed. Thus, the reader is always a central figure, the main investigator, because they are given more information than the police have.

The point of view in these narratives is shifting. We don’t see everything through the eyes of detective Elma Jónsdóttir, but rather, the point of view shifts between characters. Thus, we read more minds and are better informed, not only about the crime but also the other characters. In Boys Who Hurt, the point of view sometimes follows Kristjana, the mother of the murder victim, Þorgeir. She happens to live next door to Elma and can tell us how she comes across: “The young police woman with the mousy-blond hair and friendly face. She struck Kristjana as a bit naïve” (107).

We know a lot about Elma, but usually only because she herself has told us. Another example of Elma being shown “from the outside” appears in Night Shadows, when a young football player is called in for an interview: “Elma wasn’t exactly pretty but she was attractive in a way that Andri couldn’t quite put his finger on” (87)

This shifting perspective is especially prominent in You Can’t See Me, where it shifts very quickly between a large number of characters. This book is a departure from the Nordic Noir genre, as will be discussed further below. It does not center the investigator, and the intention is to cast suspicion onto as many characters as possible.

To Have a Hot Wife

Men who are unfaithful and refuse to take responsibility for their lives, or for their children, often crop up in Eva Björg Ægisdóttir’s books.

In Night Shadows, chronic cheater Unnar muses on how his wife, Laufey, has started to show some wear:

His wife had once been beautiful, but these days she gave little thought to her appearance. A few years ago she’d had her hair cut short and started wearing glasses – God, how he hated those glasses. They made her look at least ten years older. [...] Many of his colleagues‘ wives looked much better and seemed to care far more about their appearance. (16)

The book describes a society where men are first and foremost expected to make money and have “hot” wives, and women are expected to be educated, maintain a beautiful home, lose weight, and be World’s Best Mom. Both are cracking under the pressure and their own dissatisfaction — the husband cheats with young and impressionable women, and the wife tries to save face. The younger generation, who are prominent in the story, are living smaller versions of the messed-up adult life awaiting them.

Unnar and Laufey’s family is connected to an investigation into both arson and the murder of a young man, Night Shadows being the first book in which Elma and her colleagues investigate multiple murders.

Societal ills abound in Eva Björg’s books, but she is not interested in pure evil. Murders are often the results of human frailty and committed to cover up past misdeeds, as is the case in this book.

Women taking on responsibilities and men shirking them is a theme in Night Shadows. Women are unjustly saddled with the responsibility for pregnancy and childcare, while men do as they please. For example, Elma becomes pregnant and is not sure whether she will have the support of the baby’s father. In this, she mirrors other female characters, who are pregnant, care for infants, raise children, and lose children.

The men allow themselves to become frightened and/or angry when they are expected to take responsibility for their children. From the point of view of one male character, we are told: “Of course he loved his kids, but family life just wasn’t for him” (271).

Not Ugly but Not Particularly Pretty

Elma Jónsdóttir leads the police investigation in Eva Björg’s first three books, and in the fifth.

When Elma starts working in Akranes, she is haunted in a few ways. She has had a boyfriend for several years, but the relationship has now ended, and the reader does not find out what happened until towards the end of the book. Memories of her teen years in Akranes also disturb Elma’s peace of mind. There has been bullying of some kind, gossip, and shunning. In Girls Who Lie, she constantly compares herself to her sister, Dagný, who has a husband and children, and cultivates a good relationship with their parents:

Dagný was beautiful while Elma was … well, what she was. Not ugly, but not particularly pretty either. Perfectly ordinary. With light-brown hair, pale skin and freckles. Nothing special or memorable about her. (34)

While she is single, Elma resembles other tortured cops of the Scandi-Noir crime novel. She eats microwaved meals, has one-night stands, and is haunted by the past. However, when she settles down (in the third novel), these characteristics disappear.

Elma is not infallible, and is far from being smarter or better at solving crimes than her colleagues. For example, there are a few instances in which others point out something they find suspicious but she more or less dismisses them. Her sister, Dagný, discovers that Þorgeir, one of the victims in Boys Who Hurt, had been a victim of violence as a child. “’Thanks for telling me, but … ‘ Elma hesitated. ‘I find it hard to see how that’s relevant to his death’ (120).

Of course, this does turn out to be relevant and useful in solving the mystery. Here, Elma is nearly the polar opposite of the investigator who “has a gut feeling” about the answer to the mystery, spends every waking hour investigating it, and even breaks the law to prove their hunch correct.

Elma seldom goes off alone when investigating, but rather collaborates amicably with her colleagues. These are normal people who work nine-to-five jobs investigating crime. For example, Elma feels Hörður is on a slippery slope when she sees that he has printed out documents concerning an investigation at nearly ten thirty at night (!).

The author puts a lot of work into creating her characters, and the reader gets to know Elma’s colleagues well. Perhaps the most thoroughly fleshed out is Hörður, the head of the Criminal Investigation Department in Akranes. He suffers a personal tragedy, and his character evolves and changes accordingly. Sævar becomes more fleshed out as the series unfolds; he has a past which has not yet been fully confronted.

Who on Earth Is the Killer?

You Can’t See Me managed to surprise fans of detective Elma, who was absent from the book. The plot is more reminiscent of a whodunnit, also sometimes called as a country house mystery, which has a small cast of characters and often a delimited setting, making it unnecessary to roam too far in search of the murderer. For example, some of Agatha Christie’s stories are classic country house mysteries, and often end with all the suspects sitting in a circle in the drawing room of a stately home, listening as the investigator unravels the mystery, step by step.

In You Can’t See Me, the wealthy Snæberg family spends a weekend in a hotel on the Snæfellsnes peninsula. A body is found, but the reader is not told who has died, let alone who is guilty, until towards the end of the book. The story is structured around introducing the hotel guests to the reader. Many of them are, of course, revealed to have some skeletons in the closet, and there are many potential murderers in the group. Although Sævar and Hörður investigate, the police are supporting characters, and the crime is committed a year before Elma joins the Akranes police.

The Snæbergs being one of the country’s wealthiest families, the book touches on questions surrounding wealth inequality. Here, hotel employee Irma watches famous members of the family arrive:

They-re both so stunning that it’s almost impossible not to feel envious. Not to wonder what it would be like to be them; to be rich and beautiful and free to do almost anything you like. Go on a spontaneous weekend break to Paris, shop for clothes and buy exactly what you want. Whereas I can barely even afford to do a food shop at the supermarket without getting a sinking feeling in my stomach when I present my card. (5)

As we get to know the family better, all the usual clichés are, of course, shown to be true: money isn’t everything, and happiness can’t be bought. There is always another side. Teenager Lea Snæberg has been a victim of shunning, and had to change schools:

Sometimes I feel like I’ve spent my whole life challenging other people’s preconceptions about me – the people who assume I’m a stuck-up snob because of who my family are. (31)

Eva Björg’s characters are neither completely good nor completely bad, and all are entitled to compassion and understanding. The spoilt child can suffer just as the child who lacks, albeit in different ways.

The murder in You Can’t See Me is very tidy, so to speak. There are no decomposing corpses, or brain matter splattered all over the walls. Instead, the author uses a technique which, in fact, appears in more of her books. To provoke unease, she relates various folk tales or urban myths connected to the setting. Snæfellsnes seems to offer a wealth of material; ghost stories of Oddný Píla and stories of missing children are ubiquitous. There is foreboding in the air — and it gets under the reader’s skin.

A Serial Killer on the Loose in Akranes

After this short sidestep, the series returns to Elma in Akranes. In Boys Who Hurt, Elma is back at work after parental leave. This offers a great opportunity to create constant clashes between a demanding investigation and the detective’s home life, but Eva Björg bucks that tradition. The father of Elma’s child is at home on parental leave and her mother is helping out. Elma can give both her work and her child all the attention they deserve.

In the country house mystery, You Can’t See Me, the author paid little heed to decomposing corpses, as has been mentioned, but here, she steps on the gas. A software engineer in his early forties is found dead in a summer house. He has been stabbed repeatedly in the abdomen.

In some places, especially on the abdomen, the skin had taken on a bluish-green hue. Decomposition had caused it to swell up with gas, become puffy and start to flake off. The man’s hair and finger nails looked as if they were coming loose too. A reddish-brown fluid had leaked from his nose and mouth. His eyes were half closed, and what could be seen beneath his eyelids was pale and matt, the dried-up corneas like contact lenses left our of their solution. (5)

The bodies start to pile up and it becomes clear that in Boys Who Hurt, a serial killer is on the loose. These are crimes of revenge connected to something that took place decades before. They are rooted in neglect and violence towards children, and in bullying and shunning, two of Eva Björg Ægisdóttir’s favorite subject matters.

Shunning the Unclean Children

Eva Björg has told interviewers that she feels slightly guilty for unleashing a wave of murders on the tranquil town of Akranes. However, there are certain advantages to setting an investigation in a small town. Elma is well connected: her mother works for the local council, her sister is a midwife, and others have jobs which demand that they communicate with and know many people. Elma and her whole social circle also went to school in the area, and therefore know those involved in the investigation. There are advantages to knowing most of the locals, but there can also be disadvantages, as Chief Superintendent Hörður learns when local VIPs take offence at simply having to answer some questions. It could also be a disadvantage that an Icelander would find the idea of a murder spree in Akranes rather unconvincing, but lovers of crime fiction don’t allow this to spoil their fun.

Home Before Dark is not set in Akranes, but in the fictional village of Hvítárreykir, situated in Borgarfjörður, between Reykholt and Húsafell. Up to this point, Eva Björg’s stories have been set in contemporary time, but this one begins in November 1977. The setting then shifts between that year, and events culminating in the disappearance of teenager Stína in November 1967.

The point of view shifts between Stína in the time leading up to her disappearance, and her sister Marsí, who has returned to her childhood home ten years later, and receives a mysterious letter indicating that the murderer wants something from her. She is consumed with guilt because the night Stína disappeared, leaving only a bloody coat by the bridge across the river Hvítá, Marsí was on her way to meet a stranger with whom she had been corresponding in her sister’s name. She never made it to the rendezvous, which was in fact supposed to take place on the bridge.

Hvítárreykir is not far from Kleppjárnsreykir, and the story addresses the shunning of the girls who were imprisoned there for having relations with foreign soldiers. Here, the author touches on a social issue which has repeatedly surfaced over the past few decades. Past cruelty towards young people who deviated from accepted norms, and were viewed as a problem. A problem which was not solved, but simply moved out of sight for Reykjavík’s upstanding citizens. Eve’s unclean children, caught misbehaving or being promiscuous, and sent away into the countryside, to Breiðavík or Kleppjárnsreykir, where they were subjected to abuse. Marsí thinks of her fellow women when her investigation into Stína’s disappearance leads her here:

What kind of life do you lead after having been ostracized and sent to a workhouse for promiscuity? Had they been “cured”? Had they been welcomed back with open arms by the same communities which had ostracized them? As if they had just gone to a sanitarium to recover from a bout of pneumonia? (247)

This book strikes a new note in Eva Björg’s oeuvre, in more ways than one. Not only is it set in a different place and in the past, but Home Before Dark contains quite a lot of grotesque descriptions. The physical is used to provoke disgust and unease. A former director of the Kleppjárnsreykir workhouse is visited in an assisted living facility: “The eyes were yellowish and wet, the surrounding skin starting to sag downwards, showing a glimpse of the pink skin on the inside” (280). Descriptions of animals, animal carcasses, and disgusting food are used purposefully to provoke disgust and horror. There is a lot of material to hand, as the sisters’ parents run a chicken farm.

The slaughterhouse was in the next building. Unlike the nesting house, it was dead silent. As soon as we entered, we looked down into the white and chrome space. The small pink chicken bodies hung in rows from steel hooks, which had been hooked into one leg. In this position, the legs resembled human legs. The thighs, the calves, and the stubs at the front, as if they had been amputated at the ankle. The skin slick and glistening after the feathers had been torn off. They reminded me of newborn babies. (123)

The grotesque is one of the tools used to unsettle the reader, just like creepy folk tales and stories of old suicides. Home Before Dark may not display any rotting corpses to the reader, like some of the earlier books do, but the ambience created manages to keep the reader very much off balance.

Stories to Scare You

The crimes in Eva Björg’s books are always “personal” and motivated by passion. They are crimes of revenge or jealousy, or committed to cover up some past misdeed. Eva writes about “ordinary people”, rather than hardened underworld criminals who smuggle drugs or rob banks.

There is a tendency within the Scandi-Noir crime genre to go constantly further in inventing horrible murders, and showing bodies terribly mangled by ingenious torture. As has been mentioned, the murders in Eva Björg’s stories are rather tidy. People get hit by a car, drugged, pushed off a cliff, hit over the head or, yes, stabbed. The atmosphere and setting are created to be unsettling, but the emphasis is not on the horror of the crime, but on the mystery.

Alfred Hitchcock said that most people want to be scared. That, in fact, we find pleasure in experiencing fear and tension. At the time, this statement was considered outlandish; people who had gone through two World Wars did not find fear and tension at all appealing. Hitchcock explained that the trick was having the experience of horror and tension crafted for us, without actually being in any danger.

A crime writer’s most serious failing is allowing this desirable state of tension to be lost. They do this, for example, by writing long chapters which add nothing to the story, and don’t help in any way to solve the mystery. These days, when most people suffer from acquired attention deficit, it is necessary to regularly pull new clues from your bag of tricks — that, or give the reader a new corpse to enjoy. Authors must also keep in mind that many people listen to audiobooks read s-l-o-w-l-y, and so must be enticed with juicy morsels more frequently. If the state of tension is not sustained, the reader will wander off, start scrolling on TikTok, or getting into arguments in comments sections. Eva Björg is better aware of this than many authors, and always sprinkles clues from her sack of goodies evenly and consistently. The solution to the mystery is usually cleverly constructed in a slow and even tempo, and the reader is never left hanging with questions that have no answers.

Þórunn Hrefna 2024

Translated by Eva Dagbjört Óladóttir 2024. All quotes are from the translations by Victoria Cribb, except for Home Before Dark, by Eva Dagbjört.

Awards

Awards

2018 - Blackbird Award for Marrið í stiganum

2020 - CWA Dagger for The Creak on the Stairs

2020 - Storytel Award for Marrið í stiganum

2022 - Thrillzone Award in Holland for Best Debut Thriller of the Year, The Creak on the Stairs

2023 - Storytel Award for Þú sérð mig ekki (You Can't See Me)

2023 - Thriller of the Year in Holland for Girls Who Lie

2023 - The Blood Drop for Heim fyrir myrkur (Home Before Dark)

Tilnefningar

2021 - Nomination for Crimefest Best debut, The Creak on the Stairs

2022 - Nominated for The Blood Drop for Strákar sem meiða (Boys Who Hurt)

Heim fyrir myrkur (Home Before Dark)

Read moreHin 14 ára Marsí skrifast á við strák sem býr hinum megin á landinu. En hún gerir það í nafni systur sinnar. Bréfaskiptunum lýkur með því að þau ákveða að hittast. Marsí kemst ekki til að hitta hann en þar sem þau höfðu mælt sér mót finnst blóðug úlpa systur hennar sem er horfin. Tíu árum síðar hefur þessi óþekkti pennavinur samband á ný.. .

The Creak on the Stairs

Read moreIt had been a long day. Despite having worked late the previous night due to the discovery of the body, she had gone into the station early this morning, as had Hörður and Sævar. It was rare for dead bodies to turn up in suspicious circumstances in Iceland, let alone in Akranes, and in most cases it was easy to work out what had happened.. .