Bio

Iðunn Steinsdóttir was born on January 5, 1940 in Seyðisfjörður. After highschool she went on to study at Iceland’s Teacher Training College, and graduated in 1981. Iðunn worked for the Coastal Shipping Line from 1960 – 1962 and then taught in children’s schools for some years, both in Húsavík in the north of Iceland and in Reykjavík. Since 1987 she has concentrated on her writing career. Iðunn was a member of the board of Húsavík’s Drama Company from 1968 – 1972, and sat on the board of the Soroptimist-club of Reykjavík from 1989 – 1991. She was on the editorial board of the journal Börn og bækur (Children and Books), published by IBBY in Iceland from 1985 – 1989, and co-edited the book Dagamunur (Make a Day of It), to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Women’s Clubs Association of the People of Þingeyjasýsla South (Kvenfélagssambands Suður-Þingeyinga 1975). Iðunn was for years the chairman of Children and Books, the Icelandic department of the IBBY association.

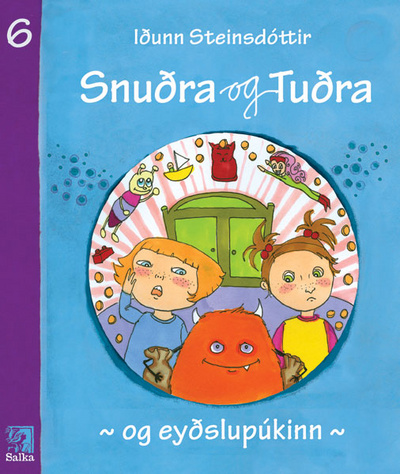

Iðunn Steinsdóttir’s first published work was the children’s book Knáir krakkar (Clever Kids) in 1982 and since then she has sent forward numerous children’s books, among them the hugely popular books about the two pranksters Snuðra and Tuðra. Many short stories by Iðunn have appeared in the children’s magazine Æskan (Youth), and she has also written stories for the children’s hour on radio and television. Iðunn has written manuscripts for television films and series for children as well a writing the manuscript for the educational film Ég veðja á Ísland (I Put My Money on Iceland), for The National Centre for Educational Materials. She has written a number of textbooks for primary schools, as well as children’s textbooks for The Icelandic Traffic Council. She has written many lyrics for songs. Iðunn has co-authored plays together with her sister, writer Kristín Steinsdóttir. Iðunn has received a number of awards for her writings.

From the Author

From Iðunn Steinsdóttir

When I was seven years old I decided to save up for a bicycle. The saving business was slow and a year later I had scraped together eight krónur, the price of a tasty bar of chocolate at the co-op. I went to my mother and asked her whether she thought I should maybe just stop saving up for the bike and buy myself chocolate for the money. She thought that was a good idea and told me to take the chocolate somewhere private and eat it all by myself. I sneaked upstairs to the bedroom and lay in my enclosed bed with the goods. The short winter day was dark but I did not turn the light on, simply lay in the darkness and ate one piece of chocolate after another. And I had day dreams; I made up stories in my head. They were mostly about us kids at Aldan and I was the main character in all the stories. The next years and decades I continued to tell myself stories and they were a big part of my life. Some times they were short stories, sometimes serials or episodes; I called them day dreams and always enjoyed to disappear into them. They were mine alone and in them I could arrange everything to my liking.

Just about twenty years ago I started to write books and plays and recently I discovered that my day dreams had disappeared. Long gone and I had not even noticed. I tried to remember when I had lost them and realised that it must have been around the time I started to write stories that were published and I shared with others.

The impact of the childhood years is strong and permanent, it is the basis and underlying in my books whether I want to or not. My mother told stories and knew all the old fairytales that had been preserved verbally. Some of them I have encountered since in the written form, others not. Amongst those are the two of the longest ones that were only told if measles or such terrible illnesses ailed the household members. Nature was alive in these tales, they where full of elves and trolls who were as real as the farmer’s daughters and princes who more often than not where the protagonists. My father was a socialist and an idealist and did not keep his opinions to himself. The idea that everyone should get an equal share of the cake that was being sliced up was part of the atmosphere and the anger caused by how unfairly the cake was being divided was palpable. My grandmother supplied the contact with God. He was almost tangible in her presence. She had always trusted him and he did not fail her. Not even during the depression-era when in the evening she did not know what she was going to put on the plates of the large family the next day.

I was just over forty when I started to write books. The first one I wrote because I was a teacher and at the time there were not many easily read books to be had in Iceland. I wanted to write an exciting book but in an accessible language so that ten and eleven year old children who had trouble reading could get through it. A book they would be proud to be seen reading, a book that the other children would also like to read. Once I had started I could not stop, it was great fun. During the first years my pupils were behind the characters but as time went on my grandchildren have started to show up. The stories about the sisters Snuðra and Tuðra are for instance based on some of the things my sons daughters get up to although they are of course exaggerated by half and then some. And then as there were more grandchildren born so also there were more stories about Snuðra and Tuðra. It matters not whether boys or girls originate the stories because those sisters are perfectly able to match any man in all their naughtiness. I am sure the reasons for any author’s choice of subject matter are many and varied and I myself have been under varied influences in my time. One has one’s periods in this as in other matters in life. In one period I looked to my youth and childhood and wrote three books that took place in the years immediately after the Second World War. I am sure that modern children find many things that were taken for granted half a century ago very strange today. But the strange can also be entertaining if you do it right. Another of my periods I like to call the world liberation period. That was when I wrote books that would allude to world affairs, such as the conflict in the former Yugoslavia and the situation in Eastern Europe after the fall of the wall. I wanted to get the readers to think about communication, shared responsibility and values.

Now I claim to have reached full maturity and only write about what I want!

My books are written for a wide age group and the reasons for writing them come from different impulses. There is however one thing that is typical for most of my books. The landscape. The mountains of Seyðisfjörður formed a ring around my childhood days, high and impressive, each more beautiful than the other. Anyone raised amongst these mountains can never get rid of them. A few years ago I meant to write a book that took place on a prairie. I had the plot ready, the characters carefully plotted and sat down to write. But after three or four chapters I got the feeling that I did not quite know what I was doing. Something was so alien that I was almost like a visitor in my own story. I wondered about this until one day I realised what was the problem. The mountains where missing. I went back to page one and moved the story into a deep and narrow valley, surrounded by high mountains. And there I connected emotionally with the characters. I moved into their valley and could follow their every move. I knew them and understood them. And then I took a look at all my books and saw that most of them were full of mountains. They were so obvious and natural to me that I had not even noticed them.

In the year 2000 I had been writing for two decades in various weather conditions. Sometimes I ask myself why I do this, why do I not stop and do something else. The answer is not to be found lying around freely. Maybe there will come a time when I will stop and start to tell myself stories again. Then I will most surely be the main character. I have regained the splendour of youth and my father, mother and grandmother will be with me when I, the author of children’s and teenagers books, stand smiling on the stage and accept the Nobel prize. My mother will be glad and proud. My father might be a little worried because the prize is not evenly distributed amongst my colleagues. But my grandmother will take it all in her stride because she knows this is all happening thanks to God.

Iðunn Steinsdóttir, 2001.

Translated by Dagur Gunnarsson.

About the Author

On the Works of Iðunn Steinsdóttir

Iðunn Steinsdóttir has, ever since the publication of her first book, Knáir krakkar (Tough Kids) in 1982, been a prolific author of children’s and teenage books. She has written for all age groups, from picture books for the youngest children to teenage and adult books. Her books have become very popular and Gegnum þyrnigerðið (Through the Thorn Hedge), published in 1991, was selected as the winner of the Prize Fund of Icelandic Children’s books that year.

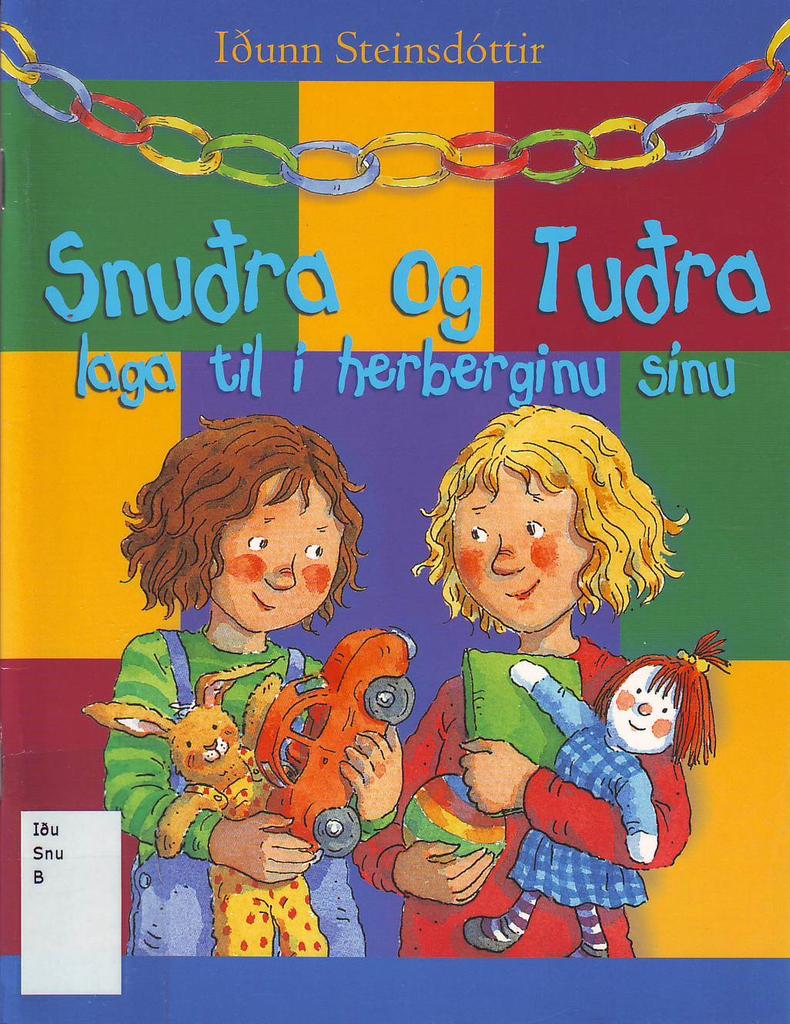

Iðunn’s books for younger children are often about kids who are pranksters and quite unruly, and of those her books featuring the unruly sisters Snuðra and Tuðra have been the most popular lately. The sisters come up with various pranks, but their mother tries the best she can to make them learn something from their experience rather than telling them off. Their pranks are often quite outrageous, as when they give away all their mother’s clothes to collect money for poor people in Africa. However they always learn the lesson they are meant to, and all ends well. Iðunn has written other picture books for children, among them Ég er húsið mitt (I Am My House, 1999), where the main character, Steini learns how he should treat his own body and show it respect. The book is written in collaboration with psychiatrists and elementary school teachers and is meant to encourage a dialogue between the person reading the story out loud and the child who is listening. The book is also meant to start the child thinking about his body and how it is treated. Iðunn has also written a few readers for school children, among them Bras og þras á Bunulæk (Hustle and Bustle at Bunulækur) which was published first in 1985, and the Viking story Litlu landnemarnir (The Little Settlers, 2001).

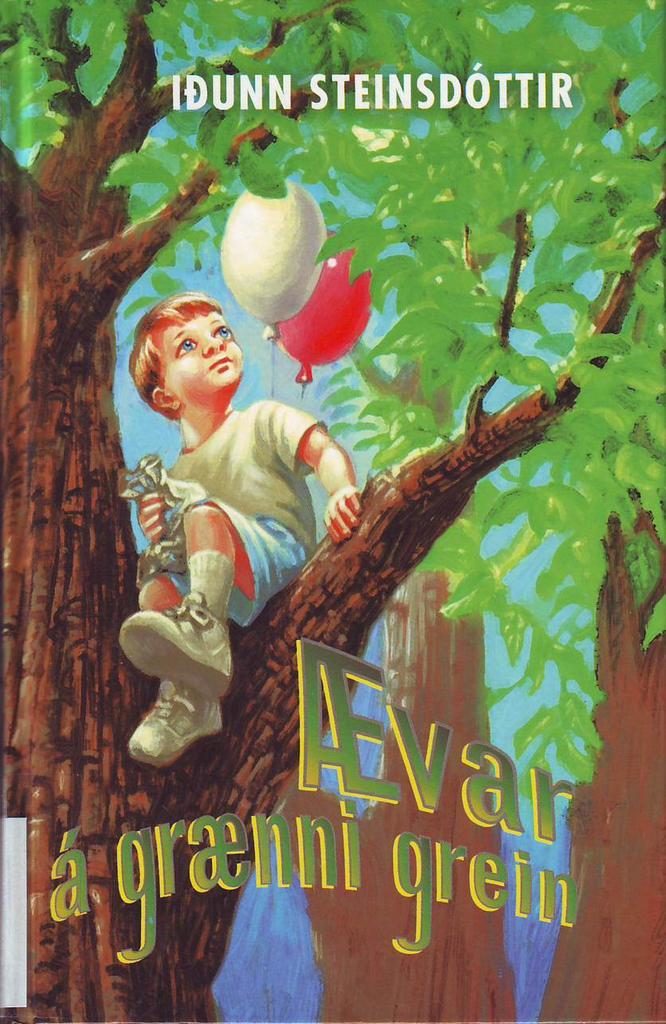

Ævar á grænni grein (Ævar’s Lucky Break, 1991, 1995) is a book for younger readers about a little Icelandic country boy who moves with his parents to France and the family stays there for a while, along with his grandmother and grandfather. Ævar is similar to Snuðra and Tuðra in being unruly and a prankster, but does not seem to learn much from experience, unlike the sisters. Ævar has difficulty adjusting to a new society and language, does not understand French and therefore cannot understand what is said to him at his preschool either. Furthermore, Ævar is not always happy about living with his grandparents; he thinks there are too many people in the house and would rather have his parents for himself. Ævar’s pranks, like Snuðra and Tuðra’s are quite imaginative, but Ævar takes himself and life much more serious than the sisters.

In the books Skuggarnir í fjallinu (The Shadows in the Mountain, 1990) and Með bómull í skónum (Cotton in My Shoes, 1994), the main characters are a group of kids who in the first books are starting school. The books are set in a small village in the post-war years and the children must deal with the problems of the time, just like the grown-ups. A mine is found stranded on a beach, fabric for Christmas clothes is in limited supply and the clothes are being reused year after year. The town is quite political in the turbulent times the book describes. None of this escapes the attention of the children. They have to deal with the difficulties of life, including death and bullies, but are also constantly making new friends and learning more about the world. These books, like all good children’s books, have a message, but Iðunn manages not to let it overpower the storyline and the children are quite typical children, fallible like everyone else and are not always capable of acting, as they know they should, despite their best efforts.

In a few of Iðunn’s children’s books, daily life is pushed aside for a more adventurous world. Fúfú og fjallakrílin (Fúfú and the Mountain Creatures, 1983) and Fjallakrílin óvænt heimsókn (The Mountain Creatures: An Unexpected Visit, 1984) are among these adventure books; in the first one, the mountain creatures, who are strange creatures of various kinds, need to find out why a terrifying darkness befalls them from time to time. They discover that it is that they treat each other badly, because the darkness does not go away until the person who did something wrong has made up for his or her wrongdoing. The message of the story to the reader is that everyone must try their best to be kind to others and live in peace and harmony with the world. In the second book, the mountain creatures are paid an unexpected visit. Refugee creatures that have had to flee from their homeland because of a terrible volcanic eruption visit them. A similar message is given here, that everyone is equal, no matter where he or she comes from and what he or she look like. The great darkness helps again to teach them this lesson, to be considerate with your neighbour and help those who are worse off than them. Children’s books with a message often tend to be boring, dry and preachy, but Iðunn is able to avoid this and her books are entertaining adventures with a little bit of wisdom hidden between the lines.

The same can be said about the adventure books Gegnum þyrnigerðið (1991) and Fjársjóðurinn í Útsölum (The Treasure of Útsalir, 1992). In both stories the setting is a different world from the one that we live in and know. Gegnum þyrnigerðið is set in a valley that is divided into East Valley and West Valley and a tall thorn hedge grows across the valley, making it altogether impossible for the inhabitants to travel between the two places. The thorn hedge is created by the evil spell of Óþyrmir, who built the wall. The people in East Valley become poor after the thorn hedge has risen and almost all their harvest goes to Óþyrmir. The people in West Valley however, continue to live as they always have, but the memory of their friends and relatives in East Valley lives on and becomes heroic tales told as bedtime stories for children.

The people of East Valley finally rebel against Óþyrmur and the thorn hedge falls, and everything seems to be going to be fine between those who have been separated. However, despite plenty of effort, adjusting to one another again proves rather difficult for those people. In the end it is the children who save the nation and show it that you cannot live like this. The story refers to the fates of East- and West Germany and the difficulties that faced the nations both before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall; and in fact still do, despite more than a decade having passed. The story offers a hope of a better and brighter future, yet it is realistic and does not play down the problems that arise after unification.

The plot of Fjársjóðurinn í Útsölum is similar to Gegnum þyrnigerðið. The story is also about how hard it is to share a country and live there in peace and harmony despite the fact that not everyone is the same. This time, the story takes place in Útsalir, where two tribes, Brekis and Maris, live together, which are very different in their physical appearance and their customs. Their peaceful co-existence is only on the surface and when their leader dies, a widespread and eventually violent disagreement arises over which group their next leader should come from. As in Gegnum þyrnigerðið, it is the children who are the country’s hope, in this case the Breki Huldar and the Mari Björt. They live in the same street and have been best friends since they were small. An Ocean Spirit gives them the task of uniting the nation and finding a treasure which will save the day, but they are overwhelmed by the enormity and difficulty of the task and do not realize that it is their friendship that is the treasure. By being friends in spite of their parents’ fighting and disapproval, they show that you can be friends with one another despite being different. The message of the story is quite worthy, but there is not a hint of sentimentality and the book is suspenseful until the last page.

Children as rescuers are a common motif in Iðunn’s books, not only in the books, which are, mixed with adventure, but also in her more realist, everyday stories. In Út í víða veröld (Into the Big Wide World, 1997) the world is full of trolls and other monsters and a small group of children, along with the mayor, who is mostly useless, must save their town from a famine. The same can be said for Iðunn’s first book, Knáir krakkar (1982), which is set in a much more mundane contemporary environment. The book is about three kids who must save various types of bird eggs from egg thieves, thereby preventing them from stealing what the children think is the country’s most valuable asset.

Olla og Pési (Olla and Pési, 1987) is partly a story about the friends Olla, who lives with a kind-hearted family of a fathers and sons in the centre of town, and Pési, a boy who has been adopted from Africa and grows up with his parents who are well off, obsessed with cleanliness and quite modern in their outlook. They are best friends and have many adventures together, deal with bullies at school and gangsters on Viðey Island, are kidnapped and held captive but are saved, and finally manage to match Olla’s “dad” with their class teacher. The story is very exciting and holds the reader’s attention completely, if perhaps a bit scary in its description of the kidnapping.

The story is also about the meeting of the old and the new, the countryside and the city, the unhygienic country girl Olla and the old-fashioned farmers who bring her up and the clean and well-dressed city boy Pési and his parents. The descriptions of Olla’s home show a fairly romantic idea of the countryside, where everyone is welcome, the food is old-fashioned and tasty and the home warm, despite being less clean than Pési’s home. Pési’s upbringing and his home are almost sterile compared to Olla, and it is meant to be a certain criticism of modern attitudes, with the human factor tending to be forgotten.

Iðunn’s books for teenagers are fairly different from her children’s books. Their tone is more serious and heavy and they deal with more grown-up issues. The message, if any, is not as overt as in the children’s books. The books are more about different kinds of teenagers and their problems and unlike her children’s books; they don’t have many hunts for criminals or a great deal of heroism. Er allt að verða vitlaust (Is Everything Going Insane, 1993) for instance, is a rather serious story about Flóki, who is fatherless, has a mother who drinks and is not doing well at school either. Until he, along with two other kids, starts working on an assignment at school with the new girl, Olga, few can be bothered to speak with him at all. Olga also prefers not to talk about her home life. His dad is gay and lives with another man and even though Olga does not have a problem with that, she suspects that others may find it strange. The group work at school brings the kids together, Flóki and Olga are both accepted into the group despite being different from most other kids, and the other kids learn that not everyone is the same and that there is no need to judge someone for being different.

Víst er ég fullorðin (Who Says I’m not a Grown-up, 1988) takes place in the post-war years and the setting, as in many of Iðunn’s books, is a small provincial town. The teenager character Soffía is described quite delicately. The book describes a time in her life when she is experiencing a struggle between childhood and adulthood. Soffía’s confirmation takes place at the beginning of the book and she thinks that she has thereby entered the world of adulthood. But the journey into adulthood is not as smooth and easy as she thinks. She is seen as either a child or an adult, depending on which is more convenient for the grown-ups at any given time. Even though it tells a story from an era that is quite removed from teenagers today, the book is very fascinating; readers sympathize deeply with Soffía and identify with her situation.

Þokugaldur (Magic in the Mist) is also about finding yourself at the border between childhood and adulthood. The book is about the teenager Valný who moves to Iceland with her parents after a long stay in Sweden. Valný is angry over having to move, and it is not until she meets Friðrik, who saves her out of a tight spot, that she gets to know other kids in town and make friends.

Music is very important to Valný and has mystical powers in her life, allowing her to open some kind of a window into the past. One night Valný sees the image of a vicar’s daughter, who lived in the same house as her hundreds of years earlier, reflected in water, and embarks on the task of finding out everything she can about the girl. Their fates are intertwined and the characters are like mirror images of each other. They are both violinists forced to choose between love and music, have to take responsibility for themselves and their decisions, and go through an intense inner struggle about which choice they should make.

Haustgríma (Autumn Mask) is the only novel that Iðunn has written for adults, a historical novel set in the Viking era. The story is based on a short fragment from Droplaugarsona Saga. The protagonist is Arneiður, a young girl who along with her mother is captured by Vikings and sold into slavery in Norway. In the beginning she rebels against her denigration as she, an earl’s daughter is made a slave, but later on she realizes that her situation is not so bad. Her owner is an old man, the master on the farm, and is only interested in using her for childcare and housework.

The story is quite brutal at times and the descriptions of the Vikings’ behaviour and their treatment of slaves are not pretty. The narrative is completely void of romanticism, the Vikings are not heroes; they are brutal robbers, murderers and rapists, who transform themselves into normal family men as soon as they return to their homes. Despite this, Arneiður’s inner life plays a more important part in the story. She finds it hard to accept her lot and show submission to her owner and does not like not having any protection or rights. She distinguishes herself from the other slaves by keeping her personality and her will. Unlike the others, her personal agenda becomes not to seek revenge, but to survive and keep her dignity.

In general, Iðunn’s children’s and teenage books are suspenseful and the story usually moves at a good pace. The reader is never bored and all loose ends are tied up. The characters are often fairly similar between books; usually the protagonists are a couple of kids, two or three of them, along with their friends, and the characters are all well rounded and convincing. In most of her books for children, the narrator is slightly older and wiser than the main characters, but at the same time stands close to them and never belittles them or pokes fun at them. The narrator does not judge their behaviour and accepts that everyone is fallible and that we cannot always do the right thing, even though we want to. The teenage books are different from the children’s books, in that they focus on one main character and her feelings. In those books, the narrator stands close to the characters; he is their equal and at the same age as them. Haustgríma is more serious than the teenage books; the account is unflinching and realistic.

Iðunn’s works are obviously diverse in nature and are not limited to certain issues or age groups. Although her adult and teenage novels may not appeal to children, her children’s books are not less for adults and the adult reader can understand some things in them that a child does not pick up. The nature of the problems and incidents dealt with in the books is such that everyone recognizes them – at some point we all have encountered bullies, fallen out with our friends or had parents who fail to understand us.

© María Bjarkadóttir, 2003.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Articles

On individual works

Þokugaldur (Misty Magic)

“On Þokugaldur (Misty Magic) Kristín Birgisdóttir and Kristín Viðarsdóttir: På tur: islandske barne- og ungdomsböker 1996”

Nordisk blad, tidskrift för de nordiske IBBY-sektionerna, 5 årg. 1997, p. 18-27

Awards

2008 – Third prize in a ghost story competition hosted by Mýrin Children’s Literature Festival and Forlagið Publishing: “Allra sálna messa” (“All Souls Mass”)

2007 – Honorary member of the Icelandic Writer’s Association

2000 – Honorary award from The Library Writer’s Fund

1997 – Hagþenkir Award (Icelandic Association of Athors of Non-fiction): Educational material for Christian studies (together with Sigurður Pálsson)

1994 – IBBY Iceland Award: Er allt að verða vitlaust? (Is Everything Going Insane?)

1991 – IBBY Honour List: Gegnum þyrnigerðið (Through the Thorn Hedge)

1991 – The Icelandic Children’s Literature Prize: Gegnum þyrnigerðið

1989 – Third prize in The Reykjavik City Theatre Playwright Competition: Randaflugur (Bees) (With Kristín Steinsdóttir)

1989 – Second prize in The Reykjavik City Theatre Playwright Competition: Mánablóm (Moonflower) (With Kristín Steinsdóttir)

1988 – The Reykjavik Scholastic Prize: Olla og Pési (Olla and Pési)

1986 – Reykjavik Art Festival Short Story Competition: “Aspadista og erfðagóss” (Aspadista and inheritance) was one of the stories selected for publication in the collection Smásögur Listahátíðar (Art Festival Short Stories)

1986 – The Icelandic Broadcastin Service Playwright Prize: 19. júní (June 19th) (With Kristín Steinsdóttir)

1984 – The National Centre for Educational Materials, competition for easy-reading material: Bras og þras á Bunulæk (Hustle and Bustle at Bunulækur)

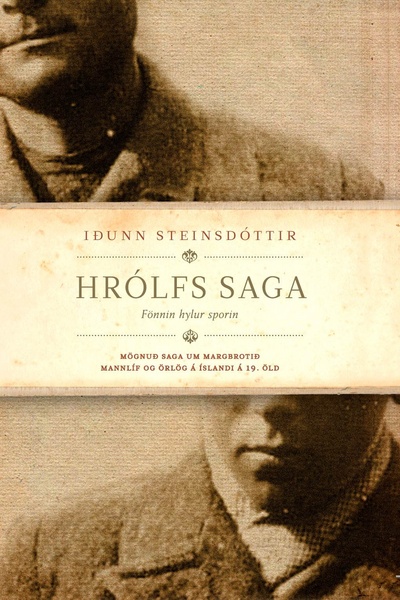

Hrólfs saga: fönnin hylur sporin (The Saga of Hrólfur: Footprints Lost in Snow)

Read moreAllra sálna messa (All Hallow´s Eve)

Read more

Ævar á grænni grein (Ævar's Lucky Break)

Read more

Snuðra og Tuðra og eyðslupúkinn (Spirit and Sprite and the Spendthrift)

Read more

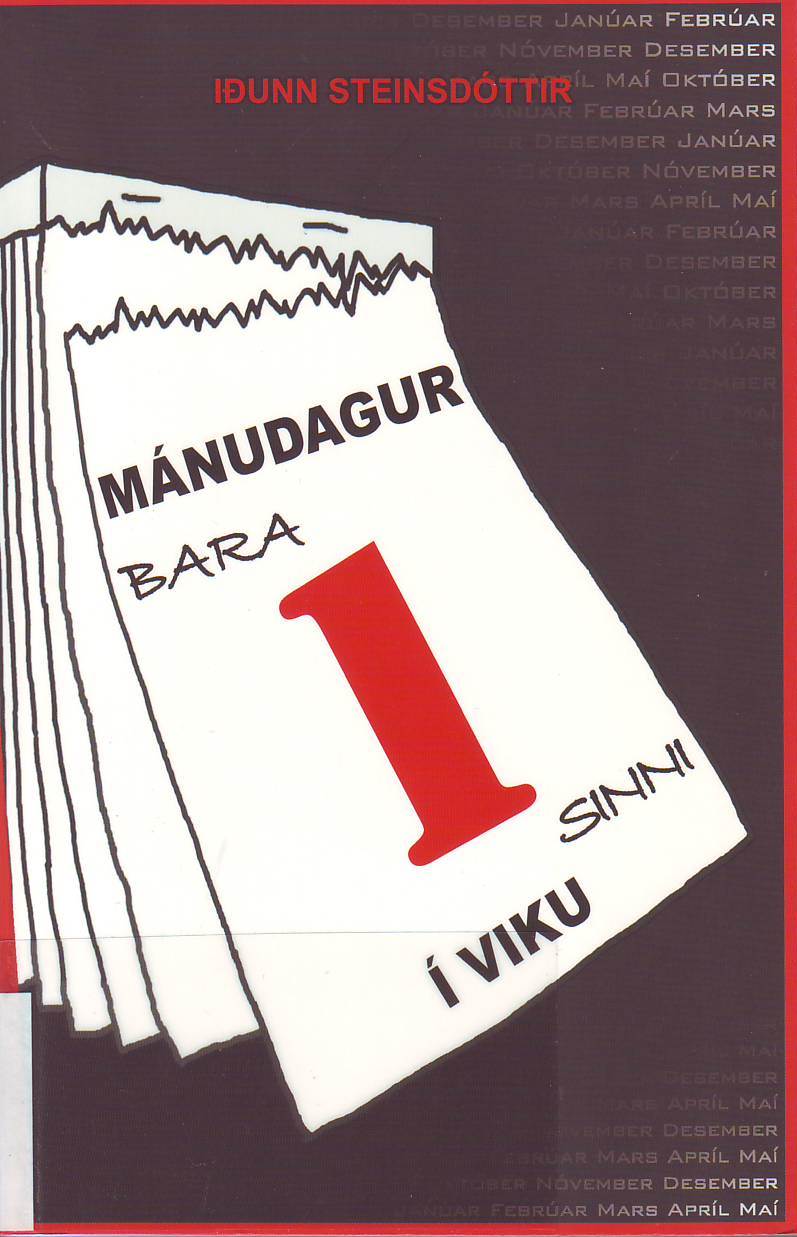

Mánudagur - bara einu sinni í viku (Monday, Just Once a Week)

Read moreSju på land, sju i sjö

Read moreDrekasag og Leitin að gleðinni (The Good Dragon; The Search for Happiness)

Read moreKatla gamla (Old Katla)

Read more

Snuðra og Tuðra laga til í herberginu sínu (Spirit and Sprite Clean Their Room)

Read more