Bio

Jón (Jóhann) Hjartarson was born on January 20, 1942 in Hellissandur. He graduated as a teacher from the Iceland Teacher Training College in 1965, and as an actor from the Drama School of the Reykjavík Theatre Company in 1968. In 1984 Jón studied further for the theatre in Berlin. Jón was for many years contracted by the Reykjavík Theatre Company, and has played a large nunmber of diverse roles. He has also acted with a number of theatre groups, such as Gríma (Mask), Litla leikfélagið (The Little Drama-Company), Litla leikhúsið (The Little Theatre), Annað fólk (Other People), to name a few. Furthermore he has a role in several Icelandic films, as well as many television- and radio-plays.

Jón Hjartarson has written a number of plays for children and adults, as well as writing books for children and teenagers. His first play, Afmælisveislan (The Birthday Party), dates from 1969. He adapted Kristín Marja Baldursdóttir’s novel, Mávahlátur (Seagull’s Laughter) for the stage, and it premiered at the Reykjavík City Theatre in 1998. Jón has directed his own plays and those by others at professional theatres and for amateur groups. He has also written various programs and shows for assosiations and institutions, as well as writing a myriad of comedy programs, talk-programs and essays.

About the Author

On the Works of Jón Hjartarson

It is nice for a change to read Icelandic children’s books which criticise society but do not allow the message to drag them down. Books which are full of joie de vivre and humour despite the seriousness of their message. That is precisely what the works of teacher and actor Jón Hjartarson are like. He has so far published three children’s books and what they all have in common is that they touch on serious issues in some way. Jón manages in all the books to handle the issues he is addressing in depth without the story becoming heavy and serious or too focused on social problems.

Apart from children’s books, Jón has written many dramatisations, of which only a few have come out in print. One is the play Mávahlátur (The Seagull’s Laughter) which came out in 1998, based on Kristín Marja Baldursdóttir’s novel by the same name. Jón has also written children’s plays which have been performed in playgrounds, and plays for adults, for instance the play Skornir skammtar (Short Supplies, 1981) which he co-wrote with Þórarinn Eldjárn.

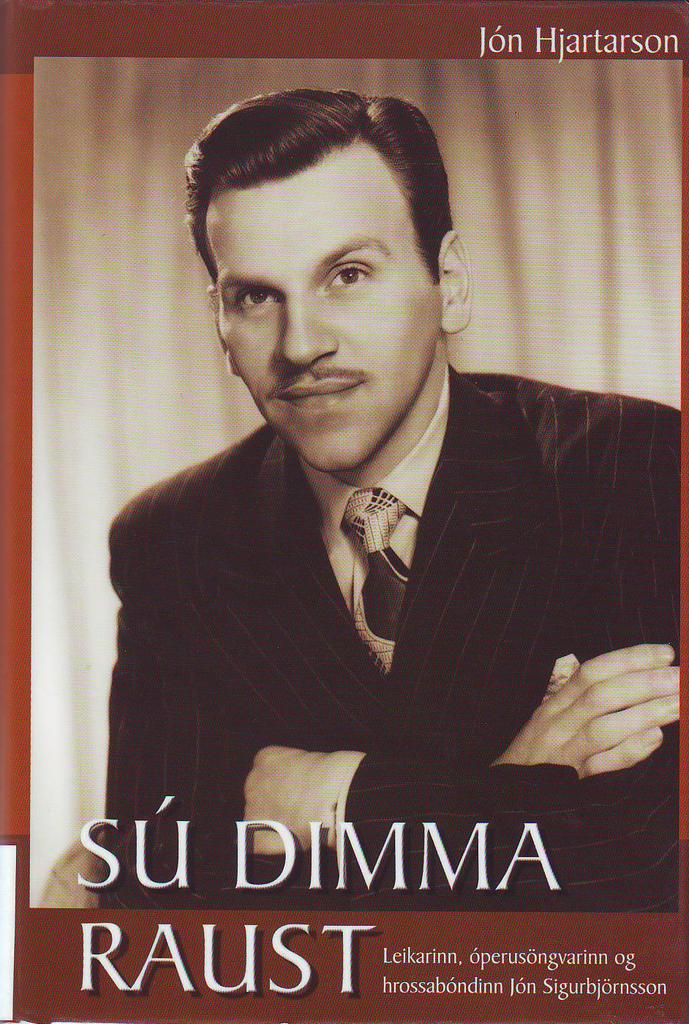

Jón’s latest book is the biography Sú dimma raust (This Dark Voice, 2001), about the opera singer, actor and horse farmer Jón Sigurbjörnsson, his life and art. Jón’s life is an interesting one, for he lived through a time of great innovation and change. His story, told through conversations between the two namesakes, is sometimes fragmentary, although this can not be considered a fault. Rather, the style has the effect on the reader that he feels as if he is sitting in the farm kitchen at Helgastaðir with the two Jóns, listening to the conversation as it takes place.

Snoðhausar (Shaved Heads, 1993), Jón’s first book, is about a group of kids who have all just moved to a neighbourhood which is called the “new neighbourhood”, to distinguish it from the “old neighbourhood”. Some of the kids have been there for a couple of months, others for a couple of days. All these children have in common that their parents are building houses, and the book shows how they experience their parents’ construction projects, which have taken over their lives for the most part. The story also describes everyday events such as birthday parties and pranks, and in general the kids’ lives during the summer which the story spans.

There is no single main character, as the story follows a few of the boys in the neighbourhood. It starts with Týr, or Angantýr, who is having his dad give him a crew cut after having seen Captain Hook get one in a film. Then the narrative is moved over to Elfar who has a birthday, to Simbi Jón and Óli, Týri’s brother. Elfar, Simbi Jón and Óli are friends and sometimes Týri is allowed to join them despite being smaller than the others.

The book is under a 100 pages, but nonetheless the kids manage to do many funny and entertaining things, of which grandma Pálína’s rafting trip is definitely a highlight. The boys build a raft to use in an enormous mud puddle which has formed inside a ditch, and get grandma Pálína to be the first one to try it. This sailing expedition ends in a disaster to say the least, and grandma is plunged into muddy water. There are more stories like this of the boys’ pranks, and another example is the following conversation which takes place on a grave in the Fossvogur graveyard, this time between Simbi Jón and Elfar:

„-Hvað borða þeir sem eiga heima hérna?

-Ekkert. Það eru ormar sem borða þá.

-Noj.

-Víst. Ormarnir breyta fólki í mold.

-Þú veist þetta ekkert.

-Jú, sko líkaminn er ekki málið þegar fólk er dautt heldur sálin.

-Hvað er sálin?

-Sálin? Það er önd.

-Áttu við svona fugl?

-Jebb.

-Eins og á Tjörninni?

-Nei, auðvitað ekki þannig. Sálin er meira eins og hnoðri held ég.“(Snoðhausar p. 34)

["-What do those who live here eat?

-Nothing. There are worms who eat them.

-Naah.

-Sure there are. The worms change people into earth.

-You don’t know about this

-Yes I do. Look, the body is not the thing when people are dead. It is the soul.

-What is the soul?

-The soul? It is spirit.

-Do you mean like alcohol?

-Yeah.

-Like liquid?

-No, of course not like that. The soul is more like fluffy I think."]

The book is obviously written in a style which is simple and suitable for young readers, lightness and humour being in the forefront.

Angantýr is indisputably the funniest character in the book, despite being only six and not having started school yet. In many cases he is the instigator of events, as when he shows up distraught and announces that his friend Gústi is drowning in a mud puddle and half the neighbourhood rushes in to save this unlucky boy, who then turns out to be Týri’s imaginary friend. Týri himself faints from the excitement after reporting the accident and is therefore unable to comment any further on the matter.

Despite the humour and the children’s pranks, they cannot escape life’s more serious sides. The parents of Dalla, a girl who is a friend of the boys, divorce and it looks like Dalla will have to move out of the neighbourhood with her mum. Elfar discovers this when hiding in Dalla’s parents’ storage room and hears her mum complain about her dad. This installs in Elfar the fear that his own parents will divorce and although his mother tries to convince him that they are not planning to at all, he remains anxious. From what Dalla’s mum says, Elfar understands that the reasons for the divorce are financial and linked to her parents’ endless worries about money, house building and the fact that they do not really own the house they are building. These are exactly the same worries Elfar knows his parents have, and this causes him to speculate about their future.

Nornin hlær (The Witch’s Laughter, 1997) is about kids who are of a similar age as the boys in Snoðhausar, but this time the main characters are the two friends Gunnur and Sara. The two girls do everything together and one evening they join the other kids in the neighbourhood in a game of hide and seek which almost ends in tragedy. They decide to hide in the gap between two rocks on the beach but as they climb inside, they fail to notice that the tide is out. They almost get trapped and are in serious danger. At the very last moment an odd lady, Albína the neighbourhood witch, comes to their rescue.

Both the children and the adults are afraid of Albína and the children are forbidden to speak to her or go near her house. The children don’t mind, as the stories which are told about her in the neighbourhood are so shocking that no one dares to go near her anyway. Sara and Gunnur are very much aware of this when Albína invites them to her home, but their curiosity and imagination, which they possess in abundance, is stronger than their fear and they reluctantly accept.

Albína turns out to be a very fun person, albeit peculiar and unpredictable, but the girls have rarely had as much fun as during their short visit with Albína in her strange house, which is reminiscent of Pippi Longstocking’s house in the story by Astrid Lindgren. At Albína’s house the imagination is given a free reign, time ceases to exists and one can travel both through time and space from her living room. Albína spins magnificent stories around all the strange artefacts she has collected through the years, stories which the girls find enormously entertaining. They are however still a little bit scared of Albína, because it is as clear as day that she is a witch.

The girls’ adventure ends suddenly when the police knocks at the door to inquire about their whereabouts. Both police and rescue squads have begun looking for them, when they were not found during the game of hide and seek and someone saw them go down to the beach. Albína hides them in the basement and pretends to know nothing about them, the girls’ imaginations take over and they begin to feel like Hansel and Gretel in the fairy tale. This would be a normal conclusion, since Albína is a witch who locks them down in the basement. When the girls are starting to become very frightened, Albína lets them out and sneaks them out of her window when the police have gone.

When the girls have returned to their homes and the search has been called of, Gunnur blurts out where they had been, although they had agreed not to say anything. Here is a clear message to young readers, presented in such a way that it neither drags down the reader nor the story. This message is that one should not, and in fact can not lie to one’s mum. Gunnur’s mom is not altogether happy about her daughter’s adventures, but following this the more serious issues raised in the book start to emerge. Albína is about to be moved to a home for the elderly but she does not want to leave. The house she lives in has been deemed uninhabitable due to bad insulation. Gunnur’s mum tries to do her bid so that Albína can continue to live in her home, but the authorities have made up their minds and neither Sara’s nor Gunnur’s parents wish to take the old woman into their homes.

In Albína’s, and later Gunnur’s mother’s dispute with the authorities one can read a certain criticism of the society we live in today, where children and the elderly often seem to be in the way and be a burden. Gunnur’s parents want to help Albína, but do not want to take her in during the winter to save her from the retirement home, and since Albína has no one else, she is cast aside in this society which does not have time to care for old women who live in houses which can be dangerous to their health.

Despite the effort of the neighbourhood kids to help Albína with her shopping and the other things the authorities consider her incapable of, she finally has to move to the retirement home, and her odd house is demolished. After the move Albína lives in a small room with another lady, despite having been promised a private room. Here the author dishes out further criticism on society and authorities who make decisions about people without consideration for the individual and go back on their promises.

The promises the authorities have given Albína, which they break, are echoed in a promise Gunnur and Sara give and are going to break. The girls decide to organise a car boot sale to collect money for children in need, and they go from house to house to collect items to sell. They get more money for the items than they are able to count and when they see this mountain of money in front of them they are tempted to keep it for themselves to buy some ice cream and sweets. Gunnur tells her mum about their plans but her mum stops them and teaches her that one should keep one’s word and if they promised to give the money to poor children then that’s what they should do. In the end the girls do this, learn a valuable lesson, and are rewarded with ice cream by Gunnur’s mum.

When the girls visit Albína at the old people’s home they see that her spirit has not been broken, despite her having been uprooted. She has decided that she will enjoy life at the nursing home and give it a chance. The reader completely sympathises with Albína at this point in the story but despite her troubles, there is no sense of hopelessness, quite the opposite. Although Albína’s house is demolished at the end of the story, Gunnur and Sara continue to play the games Albína taught them, letting their imaginations take over and transport them to unexplored magical terrain. The story ends on a positive note. Even if people are put in an old peoples home and houses are demolished, one cannot confine the mind, it goes wherever it wants to.

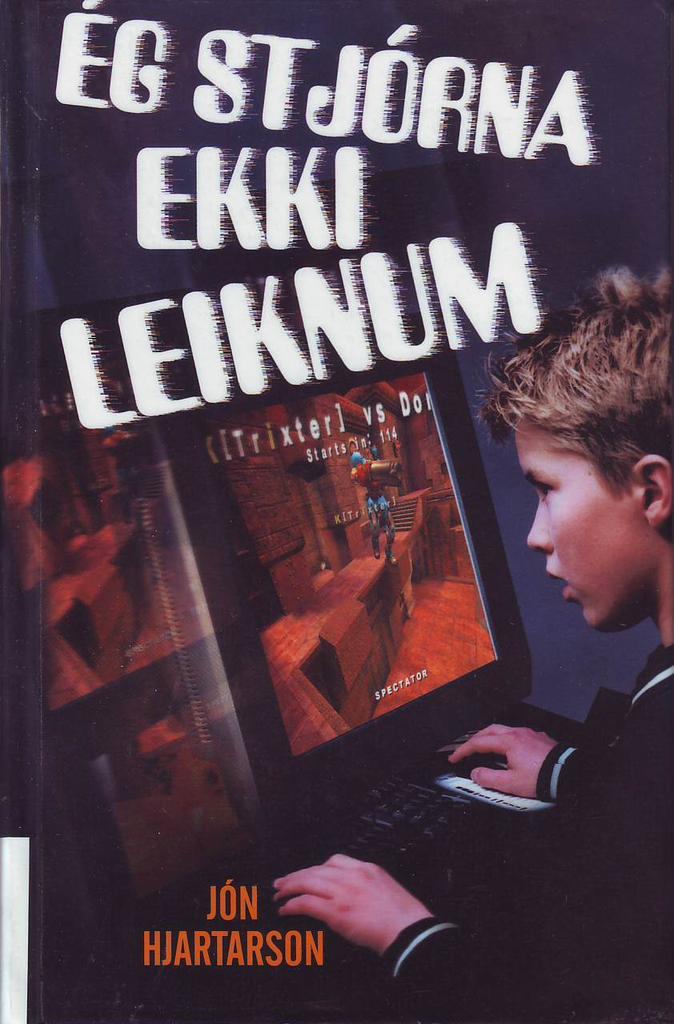

Jón’s teenage novel differs in many ways from the two children’s books, as the world of a teenager is quite different from the world of a child. Ég stjórna ekki leiknum (This Game is Beyond My Control, 2000) is much more serious than the two children’s stories, and neither funny or playful like they are. This story is about Olgeir, or Geiri, who lives with his mother and sister in Reykjavík. Geiri is in secondary school and the GCSEs are fast approaching. However, he has little interest in studying, and spends most of his time playing violent computer games.

At the annual school dance Geiri, defending his cousin from bullies, who in fact are his friends, is gripped by a strange frenzy. He attacks their leader and seriously injures him. As a result he is branded a delinquent and suspended from school right before the GCSE exams. At first he locks himself away with his computer games, but finally he agrees on his mother’s and maths teacher’s suggestion to go a small town in the countryside where his maternal aunt lives and take the exams at her local school.

Out in the country he is well received, both by his aunt and the kids at school, but he soon senses that things are not as they should be with his family. His uncle, who owns some land outside the town, appears when the kids are on a school trip and aggressively chases them away from a cave they were about to go into. Geiri later goes with his aunt to visit this brother of his grandmother, who is considered both mentally ill and senile, and he offers Geiri a summer job.

It turns out that the uncle and Geiri have much in common and their fates mirror one another in a strange way. The uncle, Finnur, had a brother who vanished. Most of the people in town believe that they robbed a sinking ship outside the town, shot the captain and that the brother ran away with the money. It emerges that a terrible crime was committed on the ship on the night of his brother’s disappearance and that Finnur had something to do with it in a similar way that Geiri was implicated in the assault on his school mate. They both break the law in order to defend someone else and when Geiri finds some old photographs at Finnur’s house he discovers that they even look very much alike.

Ég stjórna ekki leiknum is a very suspenseful story and in fact as much a crime thriller as a teenage story. The book is a far cry from a conventional teenage novel, as little energy is wasted on Geiri’s romantic interests or other teenage problems. The subject matter of the book is of a much more serious nature than teenage love and it is obviously to a great extent based on the cultural debate about computer games and their effect on children and teenagers. When Geiri attacks his school mate he feels like the monster truck he plays in the computer game. He can get past all obstacles which are put in his way and sees through any trick. Life for him at that moment becomes a computer game, and the boy he attacks merely an obstacle to overcome. The others stand powerless aside while Geiri goes berserk on his friend and this, and Geiri’s mums reaction, reflects the typical powerlessness of society, parents, schools and others when it comes to these matters.

The narrator in Jón’s works is rather neutral, and the stories are told in the third person narrative. The narrator is all-knowing and though he usually stays close to the main character he can alternate between characters if he so pleases. The same is true for the children’s books and the teenage novel, the narrator does not judge the characters or make fun of them. The humour in the children’s books does not come at the expense of the characters, rather it is expressed more through the funny or awkward situations they get themselves into.

The fact that Jón’s books are completely free of any direct discussions of social problems, without denying their existence, shows clearly that it is possible to write novels for children and young adults about life’s more serious sides in a way which awakes the reader’s interest and encourages him to read further. Jón’s novels, like most children’s books, have a message, but it is not presented in a way which patronises the reader or the story.

© María Bjarkadóttir, 2003.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Allskonar sögur fyrir börn og fullorðna (All Kinds of Stories for Children and Grown-Ups)

Read more

Órói

Read more

Í gylltum ramma (In a Golden Frame)

Read more„Leikhús í kreppu“

Read more„Brokkgeng saga leikhúsmála“

Read moreVerndarenglar (Guardian Angels)

Read moreFróðárundrin (The Wonders at Fróðá)

Read more

Sú dimma raust (The Dark Voice)

Read more

Ég stjórna ekki leiknum (I Do Not Control the Game)

Read more