Bio

Kjartan Ragnarsson was born on September 18, 1945 in Reykjavík. He graduated from the Drama School of the Reykjavík Theatre Company in 1966 and studied further for the theatre in Poland from 1968 - 1970. From 1966 Kjartan was an actor and director for the Reykjavík Theatre Company and worked there for decades. He has also directed for the National Theatre and the Student Theatre. In 2006, Kjartan and his wife Sigríður Margrét Guðmundsdóttir became the directors of the Settlement Center in the town Borgarnes. The Center is devoted to recreating Iceland’s earliest days, including one of the best-known heroes of the Icelandic Sagas, Egil Skalla-Grimsson.

Kjartan started writing plays early on, and has directed most of his own plays. Among Kjartan's plays are Saumastofan (The Embroidery Room), Blessað barnalán (Blessed with Children), Týnda teskeiðin (The Lost Teespoon) and Nanna systir (Sister Nanna) which he wrote together with Einar Kárason. Kjartan also wrote the plays Peysufatadagurinn (The National Costume Day) and Dampskipið Ísland (Steam Ship Iceland) for the Student Theatre. He has adapted a number of books for the stage, such as Ofvitinn (The Nerd) by Þórbergur Þórðarson, Ljós heimsins and Höll Sumarlandsins (Light of the World and The Summer Palace) by Halldór Laxness, Djöflaeyjan (The Devil’s Island) by Einar Kárason and Eva Luna by the Chilean writer Isabel Allende. Together wih Sigríður Margrét Guðmundsdóttir, Kjartan also adapted the novel Grandavegur 7 by Vigdís Grímsdóttir and Independent People by Halldór Laxness. The latter was shown in two parts with the titles Bjartur and Ásta Sóllilja.

Kjartan Ragnarsson has worked for the theatre in the Nordic countries, he has directed the Cherry Orchard, Street, The Seagull and Three Sisters for the Student Theatre of the Drama School in Malmö, Platonov for the City Theatre in Malmö and Grandavegur 7 for the City Theatre in Gothenburg. Furthermore he directed the play I am the Master by Hrafnhildur Hagalín Guðmundsdóttir in Gdansk in Poland.

From the Author

From Kjartan Ragnarsson

Everything I have written has been for the theatre. The theatre is my medium and working on a script has for me always been a kind of a preparation for staging the piece. Even when others have directed the plays I have written, my take on the script, while writing it, is that I will at some point direct it myself. I think I cannot write a text that will be staged, without at the same time “directing” it’s narrative in my mind. I am first and foremost a director, and working with a script is an inevitable part of a director’s preparation.

In my opinion, the theatre has been learning from working side by side with films, that script writing and directing are an inseparable whole. It doesn’t matter whether the writer and the director are the same person or not, these individuals have to work together on ideas as one unit. Writing for the theatre is only the beginning of a long process that does not come to an end until the opening night.

My stance when it comes to texts and writing for the theatre derives wholly from this perspective.

Kjartan Ragnarsson, 2001.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir

About the Author

The Problem of Being a Decent Human Being. On the Plays of Kjartan Ragnarsson

Kjartan Ragnarsson made his debut as a playwright in 1975, the International Women’s Year, with his play Saumastofan (The Sewing Factory), which was especially written to mark that year. This was followed by eleven works for the stage, a TV drama, a radio play, and nine dramatisations of novels by authors like Halldór Laxness, Þórbergur Þórðarson and Vigdís Grímsdóttir. His first plays were written in the style of comedy or farce, but despite the humour, there was a marked criticism of the prevailing values of Icelandic society. With his fourth stage play, Snjór (Snow, 1980), Kjartan had produced his first serious work which did not rely on humour to lighten up the material.

Kjartan’s works show clearly that they are written by a man of the theatre, who knows his medium well. When it comes to form, handling of the material and stage solutions, his imagination knows no bounds. In most cases he has personally directed the first stage productions of his plays, and he has experimented a great deal in his staging and looked for ways to let the framework for the performances reflect the content of the plays. A very clear example of this was his direction in Skilnaður (Divorce, 1982); where he put his actors into the auditorium of Iðnó (The Reykjavík Theatre Company), and let the audience surround the stage on four sides, imitating a boxing match to underline the subject matter: the battle of the sexes.

Kjartan is a humanist who understands people, and this is reflected in his works. He seems to have a keen eye for the comic aspects of human nature, without being blind to its faults. He is a merciless critic of his own society and the values of modern people. In many of his works he attacks fundamental questions, such as what our duties are to others and to ourselves. He always goes back to the difficulties women have in receiving acknowledgment, equality of education and real freedom in society to realise their humanity. He seems simply to be concerned with how difficult it is to be a decent human being. Yet, at the same time, he has an unwavering faith in human beings in the age of existential boredom and sarcasm.

Saumastofan is a play with songs, and it shows the lives of six women and other employees at The Stitches Sewing Factory. They throw a birthday party during work hours to celebrate Sigga’s seventieth birthday and in the course of the party, the women begin to speak more freely and tell each other their life stories through words and music. While the employees of the sewing factory tell or sing their stories, the other characters put on costumes and act out he story which is being told each time. Mixed into the fun is a debate about women’s role in society, and the question of women’s power or lack of it. The company director, Siggi, thinks for example that women are paid less than men simply because women do not support each other. If they really wanted to, they could easily improve the situation. He also thinks that the reason why few women are in high positions has to do with the fact that women do not want to take on roles that carry responsibility, because otherwise they would have done something about it already.

The two plays that followed were the farce Blessað barnalán (All the Lovely Children, 1977) and the black comedy Týnda teskeiðin (The Lost Teaspoon, 1977). In Blessað barnalán we follow how Inga, the oldest daughter of Þorgerður, resorts to desperate measures to get her four siblings to pay a final visit to their elderly mother. She is so infuriated by their unwillingness to set aside some time to visit that after sending her mother away on a group holiday she sends them a note with the information that their mother has passed away. The siblings arrive immediately to attend the funeral and the sale of the house. But Þorgerður, who knows nothing of her eldest daughter’s scam, returns home sooner than planned, because she had become bored on the trip and decided to run off. Inga is forced to explain the situation to her, but when she is going to tell her siblings everything, her mother forbids her to, because she wants to disguise herself in order to hear what the children have to say about her. Before it is over, the local priest and doctor have become involved in the plot, as well as the Bishop of Iceland himself. Like in a true farce, everything depends on misunderstanding and tomfoolery which finally is brought to a happy conclusion. But despite the farcical presentation, one can sense a certain criticism of the behaviour of the children who do not find any time to see their elderly mother while she is alive, but have decided how to spend their share of the inheritance long before her funeral.

The comedy turns considerably darker in Kjartan’s next play, Týnda teskeiðin, which criticises the double moral standard of citizens of Reykjavik of all classes. Two married couples live in the same house: on the upper floor live the nouveau riche Júlla and Aggi, who live in the shadow of Bogi, a man of wealth, and his wife Ásta, and the basement is occupied by the working class couple Begga and Baldi. To Aggi’s great dismay, a romantic relationship develops between the daughter on the upper floor, Jóa, and the son in the basement, Rúnar, who claims to be a red-hot communist. The drunken brawler Baldi gatecrashes the upstairs people’s party and they are unable to get him to leave by non-violent means. In an unfortunate turn of events they accidentally kill him and, because their conscience tells them to, decide to hide the killing. The plot of the play revolves mostly around how they can dispose of the body so that no suspicion will fall onto the respectable couple. They decide to hide the body in Júlla and Aggi’s freezer, but first they have to carve up the body, which results in a very grotesque scene, in which these classy people are covered in blood up to their shoulders, tossing the victim’s skull between them. At the same time that the respectable couple hide from Begga the truth about her husband’s death, they make a big fuss about a silver spoon which she has stolen from them. With the use of threats and bribery, they manage to make Baldi’s son and his widow their accomplices and before the end, all the characters in the play have become either thieves or murderers, and all human values can seemingly be bought, when it comes to it. But these people’s crimes are not without consequences, and soon another murder and act of cannibalism is added to the list. The play is a very well-written comedy, which even touches on the farcical in places, decidedly black and truly grotesque in many ways.

Four plays followed, in which Kjartan strikes a much more serious tone. In Snjór (Snow) he writes in a very candid and honest way about death and all the things that make people realise how powerless they are in life. It addresses the need of people today to deny their weaknesses and limitations. We observe the final days of the county doctor Einar, who has a weak heart. The couple Haraldur and Lára, who both are former students of his, have come to be his assistants. Lára and Einar begin an affair and Haraldur begins a love affair with Dísa, Einar’s domestic help, so two love triangles are taking place at once. Lára has many unresolved issues with Einar from the time when she was her student; he had practically harassed her at the university and indirectly caused her to give up her studies. In Lára’s opinion, he made her suffer for the fact that she was a woman, as he did not think she belonged in such a masculine line of study as medicine. The question of the woman’s position in society, of her right and opportunities to seek education, and her duty to herself on one hand, and to others on the other hand, is a theme which we encounter again in the play Jói (Joe, 1981), which is without doubt Kjartan’s best play. On the surface it is about society’s difficulty in offering the mentally disabled and their families the most suitable support, and the play is dedicated to the International Year of Disabled Persons, but it addresses many more problems as well.

Lóa and Dóri are a young yuppie couple, she a psychologist, he a painter. She has just been awarded a three-year grant for graduate studies in Germany and he is preparing for his first exhibition. When Lóa’s mother suddenly passes away, they face having to take care of Jói, Lóa’s mentally handicapped brother. Jói is a grown man who has lived under his mother’s wing all his life and does by no means want to go to an institution. He is child-like in all his demeanour but at the same time he is physically an adult, with the same emotions and desires as everyone else. He is therefore not just an innocent child, which becomes quite clear when he tries to rape Maggý, Bjarni’s wife. Lóa’s father and the brother Bjarni suggest to Lóa that she take care of her brother, thereby sacrificing all her duties to herself. After having tried this for a while, Lóa and Dóri eventually decide to make a deal with Jói, that they go to Germany while he stays in a home for three years, and when that time has passed they will take him in again. Through his conversations with the doll Superman, we see how Jói finally accepts having to go to the home temporarily. But although Lóa and Dóri try to find the most acceptable solution to the problem, Lóa seems to be aware of the fact that the trust between them has been betrayed. What seams to be said here, is that we really have to be our brothers’ keepers, regardless of the sacrifices we have to make.

After Jói came the play Skilnaður (Devorce), where marriage is under scrutiny again. It tells the story of a woman whose husband one day announces that he is leaving her to go and live with his mistress. She has to find her bearings in the world again. In the course of the play she manages to regain her self-confidence and as a result, when the husband wants to come back to her in the end, she is not interested in taking him back. The instructions for the stage are that the play should be performed on a round stage with the audience on four sides, so the staging of the play underlines its content in a very tactile way.

In his plays Peysufatadagur (National Costume Day, 1981), Land míns föður (Land of My Father, 1985), Dampskipið Ísland (The Steamship Iceland, 1991) and Gleðispilið (The Joy Game, 1991) Kjartan writes about people and events at certain historic times. In Peysufatadagur Kjartan paints a picture of the Reykjavík community in 1937, when Nazism was rampant and a fierce political struggle was taking place. Land míns föður describes in quite a humorous, but also a sarcastic way, how Icelanders profited from the war and finally gained their much longed for independence. Dampskipið Ísland is set aboard a ship which is on its way to Iceland in 1919, and becomes stuck in ice off the Icelandic coast for three days. The characters on the ship form a kind of a microcosm of society. Gleðispilið is about a pioneer of Icelandic playwriting and theatre, Sigurður Pétursson, the author of the first plays, Hrólfur and Narfi. Sigurður was open to the democratic movements and currents arriving from France and was outspoken in the fight for truth, equality and fraternity, which fell on deaf ears under the Danish king. He saw theatre as his platform to resurrect the self-respect and the language of the Icelandic nation.

Kjartan’s latest work, Nanna systir (My Sister Nanna, 1996), which he co-wrote with Einar Kárason, portrays in a farcical way the interactions between members of a theatre company in a small Icelandic fishing village. The entire play takes place in one night, in a warehouse which is being converted into a theatre. Two women show up unexpectedly, and this brings certain things to the surface which should have been left alone. We are introduced to the Reverend Jens Skúli, who mercilessly cheats on his wife, Gerða, who is the town’s fishing director, despised by the town’s working class. The work shows clearly a conflict between the money class and the working class, and for a while the village women attempt to rebel against the patriarchal society they live in. Eventually, all this conflict is resolved and calm is restored.

Kjartan has proven himself to be quite a versatile playwright. He has written serious works as well as farces, always with excellent results. Most of Kjartan’s works are realistic, albeit with some notable exceptions. Although some of Kjartan’s works have been quite stylised, he has never shown an interest in developing a signature style. He has primarily let the content of the works dictate the style every time, as style is only a certain way of organising the material he wants to put forward. Even though Kjartan has in recent years increasingly turned his hand to stage adaptations of well known novels, to great popularity, one hopes that he will find time to write more plays.

© Silja Björk Huldudóttir, 2001.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 578

Tvö hús (Two Houses)

Read moreRauða spjaldið (The Red Card)

Read moreSjálfstætt fólk - Ásta Sóllilja (Independent People - Ásta Sóllilja)

Read moreSjálfstætt fólk - Bjartur (Independent People - Bjartur)

Read moreGrandavegur 7

Read moreNanna systir (My Sister Nanna)

Read more

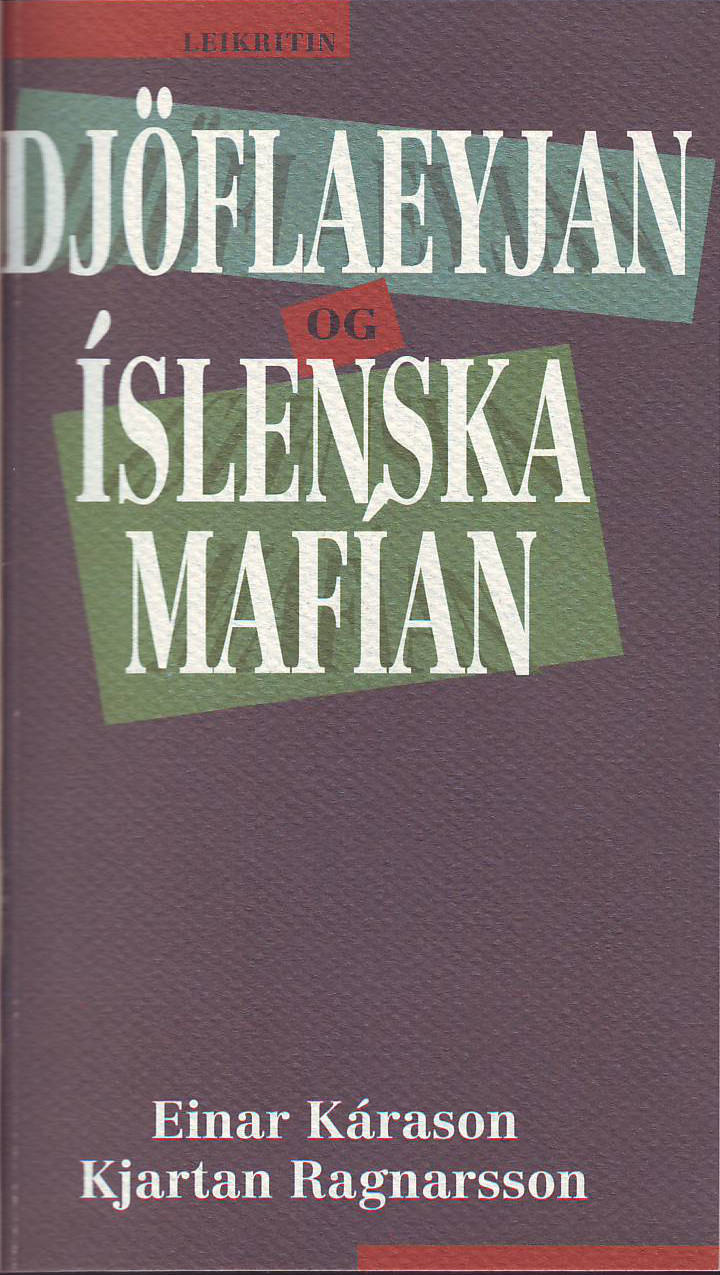

Leikritin Djöflaeyjan og Íslenska mafían (The plays Devil island and The Icelandic mafia)

Read moreEva Lúna

Read moreDampskipið Ísland (The Steamship Iceland)

Read more