Bio

Margrét Lóa Jónsdóttir was born in Reykjavík on the 29th of March, 1967. She studied Icelandic and phylosophy at the University of Iceland, and phylosophy the University of San Sebastian in Spain, graduating with a B.A. degree in 1996.

Margrét Lóa writes poetry and her first published work, the poetry collection Glerúlfar (Glass Wolves), came out in 1985. She has been the publisher of many of her own books and has also designed and illustrated them. In addition to her poetry books, Margrét Lóa has conducted a sound structure which was performed in the gallery Hlust and a book-art piece for Gallerí Barmur (Gallery Chest; a moveable gallery situated on people’s chests). She has been a creative writing teacher at workshops run for children by the Reykjavík City Library and also in the Gerðuberg Cultural Center in Reykjavík. She was the editor of the literary magazine Andblær for two years.

Margrét Lóa has worked in galleries and art institutions, as an exhibition guide for the Reykjavík Art Museum at Kjarvalsstaðir and a PR person at the Nordic House in Reykjavík. She has also done radio programs for the Icelandic Broadcasting Company RÚV, among her issues there are feminism and gender equality.

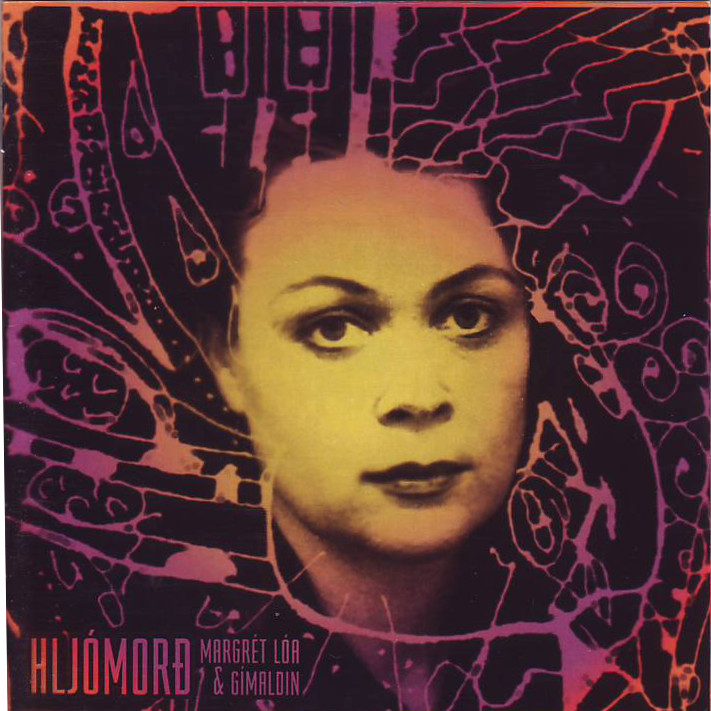

In 2003, she released the CD Hljómorð, containing her poems, together with the musician Gímaldin (Gísli Magnússon). They introduced this piece at the Gothenburg Book Fair in the Fall of 2001.

Margrét Lóa Jónsdóttir lives in Reykjavík.

Publisher: Salka.

From the Author

Why do I write?

I walk up to a secret door which is open. Of course I go in. Sneak out of the everyday, transform it, curse it or sing its praises. Sometimes I think this is wonderful, sometimes awful, and everything in between. Gradually I have grown dependent on this insistent wonder.

Words that are born

Some words are born

(literally speaking)

small and weak.

Some scream.

Yet others are calm and quiet but prove to be on closer inspection shy and even afraid that people will laugh at them.

Others are self assured and are eager to appear in poems -

convinced that their shape or flavour - will move poetry lovers.

Some words are born under cruel conditions.

Others are born without effort yet hit the bull's eye.

Words are born when hearts beat in sync –

or when hearts are blown

to pieces

and blood seeps from wounds

In other words:

When the unbearable has the upper hand.

The poet's un-poetic pain

carefully draped in words

bundled up in modernity -

painted both poetically and abstract ...

(Because anyone who knows the comfort of poems will not throw them overboard.)

Sometimes words gather in poems

so sincere and serious

that many regard them as silly.

I don't know ...

Generally people enjoy words.

And many say: (from a pure love of words)

Sincerity is all you need

Silly nilly words.

Glorious silly nilly words.

Margrét Lóa Jónsdóttir, 2004.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

About the Author

Love of poetry: The loudest voice in Margrét Lóa Jónsdóttir’s head

Self-publication has a sound tradition on the Icelandic poetry scene, and the tradition for poetry has been robust among Icelanders ever since poetry was our second largest export in the Viking times, after homespun cloth. This independent publication has had its fertile periods; it is safe to say that during the post-war years this publication grew strong and the most recent period of productivity was the eighties. During that period independent voices emerged that were later to become fixtures in Icelandic literature, contracted by publishers: Gyrðir Elíasson, Sjón, Bragi Ólafsson, Ísak Harðarson and Kristín Ómarsdóttir all published their first books of poetry themselves. Even though the eighties were the most celebrated period of self-publication, they did not expire after that, and the nineties have also witnessed some activity, younger authors such as Guðrún Eva Mínervudóttir, Stefán Máni and Steinar Bragi all published books by themselves before being contracted by publishers. Others include Bjarni Bjarnason, who had published books for a long time before his novel Endurkoma Maríu (Maria’s Return) was picked up by a publisher, and Óskar Árni Óskarsson, Sigurlaugur Elíasson and Geirlaugur Magnússon who have published their books with small independent publishers. Such publications are often close to self-publications.

Even though this kind of publication has quite a tradition, as already claimed, it has not been respected as it should, and is often patronised on the assumption that those poets who publish on their own are not good enough to gain access to real publishers. It is difficult to agree with this point of view, particularly in view of the book market and poetry’s weak position within it, books of poetry do not sell well and are generally seen as a unprofitable choice for publishers. On the other hand the number of people writing poetry is clearly large, and poetry is easy to publish independently. Obviously the quality is uneven, but this applies also to the poetry output of the publishers, who do not always necessarily skim the cream of the material that is on offer.

Self-publication often offers more freedom in book design, not only because here the imagination of the designer is allowed to roam free without the supervision of conservative publishing standards, but also because often these books are not printed in large numbers and thus it is easier to fuss a bit over the design. Thus many of these publications are quite beautiful pieces and come close to being artwork, book-art. One of the poets who has made an art out of self-publication is Margrét Lóa Jónsdóttir, who was one of the poets to appear in the eighties, participating in poetry readings hosted by The Poem’s Best Friend. Her first book of poetry, Glerúlfar (Wolves of Glass) (1985), was screwed together with screws, the cover was plastic. The book was published by Medusa, a poetry and happening group that was most active in the first years of the decade. Margrét Lóa once described to me how she had walked among people in coffee houses to offer the book for sale – this was the way most poets sold their self-publications – dressed in a short skirt with red lipstick. Her would-be-buyers looked at her in amazement, saying – are you a poetess? Publishing this book? In this way the selling of the book became a kind of happening, for Margrét Lóa’s look and style clearly did not fit the preconceived image of a shy poetess (or whatever the image of a poetess was at the time?).

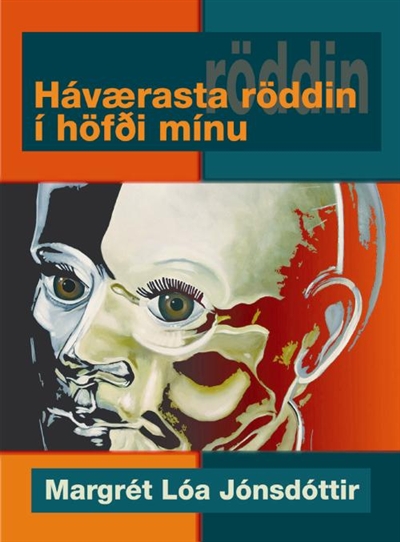

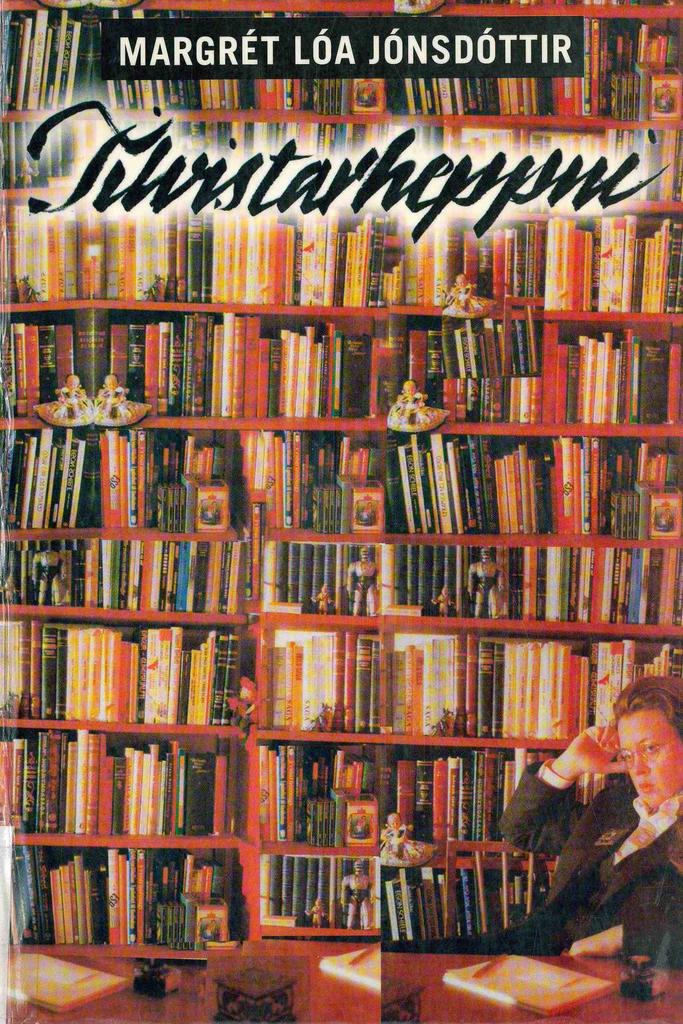

Náttvirkið (The Fortress of Night) (1986) was published by Flugur, an independent publishing house run by Hrafn Jökulsson, named after the publisher’s first publication, a reissuing of Jón Thoroddsen’s book of poetry from the early twentieth century, Flugur (Flies). Hrafn was at the time the driving force of the aforementioned poetry group The Poem’s Best Friend, that hosted numerous readings in the eighties and is still active, while not as prominent now. The third book, Orðafar (Travelling with Words) (1989) is signed Marló at the back of the cover, similarly to Margrét Lóa’s fifth book, Tilvistarheppni (Fortune of Being) (1996), Marló being the name of Margrét Lóa’s own publishing house. For even though her fourth book, Ávextir (Fruits) (1991), was published by the the publisher Mál og menning, she continued to publish unusual books of poetry by herself. Following upon Tilvistarheppni, Ljóðaást (Love of Poetry) appeared in 1997, containing three poems that all read as a kind of a declaration or a manifesto on writing poetry. The book is very small, it fits into your palm and the cover consists of two pieces of fibre chips with wooden boards glued on at the back and front. On the front an image is glued on, that seems to be an old landscape painting showing a waterfall, but the unrealistic spread of flowers in the foreground makes the image look simultaneously realistic and a little absurd. No title is to be found on the cover, designed by Margrét’s partner, Jóhann L. Torfason. The book is illustrated by Margrét herself, as are most of her books, apart from Ávextir, illustrated by Jóhann and Tilvistarheppni, which is not illustrated, similarly to Margrét Lóa’s most recent book, Háværasta röddin í höfði mínu (The Loudest Voice in My Head), published by Mál og menning in 2001. That same year Marló published Margrét Lóa’s selected poetry, Úrval (Selection), which is a kind of book-art like Ljóðaást. All her books have an unusual look, with catching covers and it is clear that the design is well thought out, even though only Glerúlfar, Úrval and Ljóðaást look very different from conventional books of poetry.

Thus it is safe to say that Margrét Lóa has turned self-publication into a certain art, some of her books are called book-art and she has exhibited them here in the Reykjavík City Library (2000) and elsewhere. She has also staged a sound-art in Gallery Hlust in 1997, where the long poem “Draumey” from Tilvistarheppni sounded. In addition to this she has published the spoken word CD Marló, with poetry readings and music, together with Gísli Magnússon. She is furthermore very conscious of the status of the poem (believed by many to be weak) and has given a paper on this theme at a Writers’ conference in 2000, as well as editing the magazine Andblær (Breeze), an ambitious poetry and art magazine, also characterised by an attentive and beautiful design.

From this it should be clear that Margrét Lóa is also very conscious of her own place as a poet, and the poem itself and reflections on poetry are a distinct theme in her later books. The first four books are rather surrealistic and more in the style of the Medusa-group than the poetry characteristic of The Poem’s Best Friend readings. This difference appears quite well in the first verse of the poem “Fortune of Being” (“Tilvistarheppni”) from the eponymous book, where it describes how the poetess is walking down the street Laugavegur in Reykjavík and somebody calls to her: ”- Hey you, didn’t you publish a book of poetry.../and wasn’t it called something with glass?” (“- Hei þú, gafstu ekki út ljóðabók.../og hét hún ekki eitthvað með gleri?”) The poetess reflects on the fortune of being, and the fragility of poems, glass and people: “- So it is you?/- Of course, I say amenably./- You know, we don’t understand shit/in your poems!” (“- Svo þetta ert þá þú?/- Auðvitað, segi ég vingjarnlega./- Veistu, við skiljum ekki rassgat/í ljóðunum þínum!”) Even though the poems of Glerúlfar were opaque, anyone can understand this poem that is about poems, and to be a poet that nobody understands – but is still memorable. “And the fortune of being?” (“Og tilvistarheppnin?”) it says later in the poem, “To love/and eat/and be good at/pretending...” (“Að elska/og matast/og vera flinkur við að/látast...”)

The reader must connect the fortune of being to the poem itself, for a few verses later the narrator shouts “Hurrah for the urge for writing!/Hurrah for the poetic reality!” (“Húrra fyrir skrifþörfinni!/Húrra fyrir hinum ljóðræna veruleika!”) In the last verse it comes to light that the bottom drawer contains not heart rendering poems but a scull of glass “which is supposed to remind me/of the unforeseeable time of death” (“sem á að minna mig á/dauðans óvissa tíma”). This scull is also related to the fortune of being and the poem ends with these lines: “Life is wonderful./Life is a trembling mad plant.” (“Lífið er dásamlegt./Lífið er skjálfandi brjálað gras.”) Here the poem and life seem to merge into one, in a reference to a psalm – the national anthem – and a song celebrating alcohol.

Long poems are common in Margrét Lóa’s books, where one theme is being thoroughly worked through, or the poems are linked together with common threads. An example of this are the wolves of glass – or just the wolves – appearing regularly in the poems in Glerúlfar. The poem “Wolves of Glass” (“Glerúlfar”) goes like this:

Afsprengi draumsins

gaf von minni

hamslausan dauða.Um morguninn afsanna ég tilveruna.

Svíf um í óendanlegu vatni

bakvið fagurbláa skóga

og engi.Og vatnið. Vatnið

strýkur glerúlfa á braut.[The offspring of the dream

gave my hope

furious deathIn the morning I refute existence

Drift in endless water

behind royal blue forests

and fields.And the water. The water

caresses glass-wolves away.]

In “There Will be Nights and Advices” (“Koma nætur og ráð”) “you” (“þú”) turns out to be “a malefactor not a wolf” (“vargur en ekki úlfur” – ‘vargur’ is another word for wolf, also meaning malefactor) and in “Going in a Circle” (“Hringferð”) being solitary is gold among wolves of glass.

Even though the reflections on writing and poetry are mainly noticeable in the later books, they can be seen also in Náttvirkið in the long poem “Alexía’s Secret Document” (“Leyniskjal Alexíu”). The poem is highly surrealistic and tells the story of a young girl, Alexía, who is involved in some mysterious business, possibly only because she is in love with a member of the “movement” and it appears that following upon that she is imprisoned in a castle – possibly a mental hospital – where she finally dies, betrayed. Alexía writes a diary, where she puts down the time of day, not the day itself, and she burns it because she seeks herself “not anymore among useless words” (“ekki lengur meðal fánýtra orða”) but still continues to write into it her own moment of death and a visit to the deceiving lover:

5.10

Svört augu fálma gegnum ísbreiðuna.

Nálgast rispuförin á bakinu. Það skellur

í stálgrindunum. (Lykli er stungið í

skrá.) Ég hrekk upp með andfælum. Faðma

loftið og ósýnilega veggina. (Þetta

hlaut að vera eins konar þú.) Hunangsblá

ljósbrot fylla herbergið og ballet-

dúkkan stígur upp úr bleiku vatninu.

(Syngur þér þrjá sálma.) Stuttu síðar

finn ég samastað á jörðinni. Hvíslandi

í þokunni: Ég veit hver sveik.

Fótatak varðarins fjarlægist og lágróma

raddir bergmála í hvítum ganginum:

Alexía er dáin.[5.10

Black eyes are fumbling through the field of ice.

The scratches on the back come closer. The bars

slam. (A key is inserted into a

keyhole.) I wake up suddenly. Hug

the air and the invisible walls. (This could

only have been some kind of you.) Honey-blue

fragments of light fill the room and the ballet-

doll steps out of the pink water.

(Sings three hymns for you.) Shortly after

I find myself a place on earth. Whispering

in the fog: I know who betrayed.

The footsteps of the guard fade into distance and murmuring

voices echo in the white corridor:

Alexia is dead.]

The poem is effective and ages well, insanity and pain grapple with each other in descriptions that are full of impatience and obsession. In many ways the poem “Fact” (“Staðreynd”) in the section “Journey” (“Ferðalag”) in Orðafar describes the emotion evoked by Margrét Lóa’s poetry in these first books:

farþegarýmið er á stærð

við appelsínu

mér er skítsama

sit klofvega á ótaminni hugsun

og er þar af leiðandi

þráhyggjusjúklingur[the passenger’s compartment

is the size

of an orange

I could not care less

riding an untamed thought

and am thus

insanely obsessive]

Here we see the emotions that characterise the poem about Alexía and other impressive poems by Margrét, a claustrophobia mixed with untamed imagination. The conflict between these creates tension in the poems and this makes them enjoyable and memorable, but not necessarily transparent, as the clueless but fragile readers appearing in “Fortune of Being” (“Tilvistarheppni”) discovered. This tension also materialises succinctly in the poem “Eindhoven”, where “the five women/in the five houses/right across/have put on dotted nylon dresses/and eat breakfast/with five husbands” (“konurnar fimm/í húsunum fimm/beint á móti/komnar í doppótta nælonkjóla/og borða morguverð/ásamt fimm eiginmönnum”). The narrator who is watching this through a spy-glass has some instant coffee and feels hungry. She has not spoken to anyone in a week and thinks that she must soon go mad: “with the spy-glass/the five philips-toasters can be discerned/behind the five inner curtains/that are all identical” (“með kíkinum/má greina philipsristavélarnar fimm/á bak við stórrisana fimm/sem allir eru nákvæmlega eins”). It is almost like Alexía is here again and the reader does not know whether he should assume that the narrator has lost himself in this spying business and has become paranoid, or if this is a feminist reflection on the monotone of the everyday family life, clearly barred for the narrator. As indicated by “Eindhoven” the poems in Orðafar are generally not as surrealistic as those in Náttvirkið, particularly those that appear in the journey section. Another example of this is the poem “Closer and Closer” (“Nær og nær”): “he crawls from under the door/and charms all the hotel guests/this 5 meters long ant” (“hann skríður undan hurðinni/og heillar alla hótelgestina/þessi 5 metra langi maur”). Here the reader cannot make up her mind whether the ant is really 5 meters long, or if this is a 5 meter long row of ants, or if the ant is unusually big and the narrator perhaps exaggerates a bit.

Another version of a feminine everyday appears in the first part of the poem “Shot” (“Skot”) in Ávextir:

Um morguninn: Fer fram úr (með lokuð aug-

un). Þreifa á veggjunum, engin skilaboð frá

öðrum hnetti, en á morgun yfirvofandi styrjöld.

Líklega rökrétt afleiðing suðupottarins þarna

niður frá. Hnýti um mig bláa kínverska silki-

sloppinn. Annars þægilega svalt frammi. Sting

tánum í inniskóna, hætti við – betra að koma

blóðinu á hreyfingu. Hollt að skjálfa dálítið.

Teygi mig í blaðið, les, dýfi hrökkkexinu ofan

í apríkósumarmelaðið. Finnst smjör ekki leng-

ur skipta máli en uppveðrast af sykri.[In the morning: Step out of bed (with closed eye-

s). Pat the walls, no messages from

another planet, but tomorrow a war in the making.

Possibly a logical result of the boiling situation down

there. Tie the belt of the blue Chinese silk bathrobe

around me. Still it is comfortably cool. Put

my toes in the slippers, change my mind – better to get

the blood moving. Healthy to shake a little.

Reach out for the paper, read, dip the biscuit into

the apricot-marmalade. Find that butter does not matter

anymore but get all exited about sugar.]

What begins in a surrealistic way suddenly changes into realistic political references (as appropriate today as it was then) and the reader wonders if this is not just a fairly ordinary morning moment – again exaggerated a bit. Don’t we all avoid opening our eyes to the day for as long as we can and fumble our way half blind in the early morning? For then the everyday takes over with the newspaper, the biscuit and the marmalade. In the next part of the poem we seem unexpectedly to be back on a journey, and the narrator holds a diary – perhaps an echo from Alexía? It turns out to be difficult to “keep a diary and travel on trains” (“halda dagbók og ferðast um í lestum”) but the narrator tries to “write down every detail.” (“skrifa hvert smáatriði niður.”) A young man sits down beside her, he turns out to be Indian and stares at the narrator with blue lips. Suddenly he falls towards her and the head “hangs forward so wires can be seen.” (“slútir fram svo sér í víravirki.”) The narrator gets goose-flesh but still she pats his warm chest and finds small nipples and a Velcro on the heart: “Pull from out there some wires and a small Sony-tape recorder.” (“Dreg þaðan snúrur og lítið Sony-kasettutæki.”) She is relieved and she takes out the batteries and throws the gadget out of the window. Here we have a movement contrary to the one from the first part, for what seems at first to be an innocuous train journey where the main problem is to keep the diary going is transformed into a unexpected event with a mechanical Indian.

It is clear that reflections on writing is a recurrent theme in Margrét Lóa’s poetry, even though it does not become cohesive until the publication of Tilvistarheppni, Ljóðaást and Háværasta röddin í höfði mínu. The loudest voice in the poetess’ head is of course the poem, and as in “Fortune of Being” (“Tilvistarheppni”) it is always connected to transitoryness and death, for it is also “the great reminder of death” (“dauðaáminningin mikla”) as it says in the poem “The Most Hurtful Crying in the World” (“Sárasti grátur í heimi”). “The poem keeps me away from madness/with its humorous seriousness” (“Ljóðið heldur mér frá sturlun/með sínum spaugilega alvarleika”) but everything that the poetess writes is plain and harmless compared to “the dark poem/that resides inside of us all.” (“hið myrka ljóð/sem býr innra með okkur öllum.”) And we are reminded again of the impatient tension of claustrophobia and vent when it comes to light that the poetess needs comfort and soothing, but the words in her head demand ecstasy: “They behave/like mad seagulls/that have recently/found something to eat.” (“Þau hegða sér/líkt og óðir mávar/sem nýlega/hafa komist í æti.”) She calls upon the words, asking: “What about lovely little butterflies?/You do not want to look like them.” (“Hvað með lítil yndisleg fiðrildi?/Þið viljið ekki líkjast þeim.”) There is clearly a lot of exasperation in the soul of the poetess, but later she is out of the surge in the section “Sometimes I Think that All Poems are Good” (“Stundum þykja mér öll ljóð vera góð”). The poem “Hymn to Poetry” (“Ljóðalofgjörð”) describes this atmosphere well, and it goes like this:

Í harðæri jafnt sem góðæri

er ljóðið skemmtilegt hljóðfæri.Kertaljós og

snjór á glugga ...Stirndur himinn ...

Hógvær ljóð sem hástemmd ...

Sterk sem veik ...

Stundum þykja mér öll ljóð vera góð!

[In bad years as well as good years

the poem is an enjoyable instrument.Candle light and

snow on the window...Starry sky...

Modest poetry as well as supercilious...

Strong as well as weak...

Sometimes I think that all poems are good!]

It is not uncommon for poets to start, with time, to reflect on their own poetry, its place, language and form, as Margrét Lóa does in her recent books. However, it is safe to say that such reflections in poetry have increased in the last few years, and one could name Þorsteinn’s frá Hamri most recent book of poetry, Meira en mynd og grunur (More Than an Image or Suspicion) (2002), as a good example. Others include Öll fallegu orðin (All the Beautiful Words) (2000) by Linda Vilhjálmsdóttir, and poems in recent books by Sigurður Pálsson and Baldur Óskarsson contain musings on the poem’s condition.

In Tilvistarheppni these ruminations appear in the girl Draumey who can not sleep at night, she thinks about men and the world, culture and art: “Write/just as fast/as you can read those words/Write/in my blood// impertinent/yet modest.” (“Skrifa/jafn hratt/og þú nemur þessi orð/Skrifa/með blóði mínu//í senn ófyrirleitin/og hógvær.”) This “you” is probably the reader for Draumey does not seem to be addressing anyone in particular in this long poem. But who is Draumey? She is in many ways reminiscent of Alexía and as a poet she could be the author’s alter ego, the one who lives in her dreams. Draumey crafts words during the night, she thinks and asks questions but no one hears her words, she is “all at the same time/a line of poetry, mother, barren/poetess,//I who am the deepest desire in every man.”(“allt í senn/ljóðlína, móðir, óbyrja/skáldkona,//Ég sem er dýpsta þrá sérhvers manns.”) As such she is the image of the muse, the goddess of poetry and even recalls the blue flower in romantic poetry. But she is also the feminine image of the poetess, and in Margrét Lóa’s more recent books the idea about the woman becomes more noticeable, as for example seen in her reflections on being a mother. This image of the mother is very beautiful in the poem “Some Words” (“Sum orð”) in Ljóðaást, where the poem is described as a butterfly-net, and moments are rare butterflies that the narrator wishes to catch in her net. One moment is very close:

– Ég sit skrifandi

upp við dogg

með ungbarn

mér við hlið.Litlar tær

gægjast

undan sæng...Allt

vil ég

með

orðum

veiða...Þó ekkert gæti

skýrt mitt lán.-[I am sitting writing

in my bed

with an infant

beside me.Small toes

peep

from under the duvet...Everything

I wish

to hunt

with

wordsEven though nothing could

explain my happiness.]

Here it becomes clear that the butterfly-net cannot grasp every moment – or what? In this way the love of the poem merges with the love for the child and that merger reaches the lover as well, and in Tilvistarheppni and Háværasta röddin there are long and beautiful love poems. “Love Poem” (“Ástarljóð”) is the title of one of the long poems in Tilvistarheppni, where the poetess is discussing love with Amor.

Guð ástarinnar – Amor

færir þér súkkulaði og rósir

en mér réttir hann

penna og blað

(svo ég geti dásamað

augu þín í ljóði.)[The god of love – Amor

brings you chocolate and roses

but to me he brings

pen and paper

(so I can marvel at

your eyes in a poem.)]

He asks the narrator of the poem: “You love him?” (“Þú elskar hann?”) and she asks: “We have a jewel together” (“Við eigum saman gimstein”), “A jewel,/that cannot be divided up between us.” (“Gimstein,/sem ekki er hægt að skipta á milli sín.”) The poem “Good Days” (“Góðir dagar”) in Háværasta röddin í höfði mínu seems almost to be a sequel to this discussion with Amor, it begins by describing how angels are connected to the love between the narrator and her lover. They have two angels, and the first thing he gave her were to images of angels. The first summer together they stayed in Rioja and seven years later they return there and find wine made from their first summer’s crops: “with two angels on the label...” (“á flöskumiðanum voru tveir englar...”) In the poem “An Ordinary Love Poem” (“Venjulegt ástarljóð”) the poetess again gives up the attempt to bring a moment into the poem-net, and she is certain that she will “never/really manage/to write a poem/that can express/my feelings/for you” (“aldrei/almennilega takast/að semja ljóð/sem gæti tjáð þér/hvaða hug ég/ber til þín”). Still the poem “A Summer’s Day” (“Sumardagur”) must come close. The Narrator describes how she is observing her lover from a distance, like she has never seen him before:

Líkt og fugl á flugi

sem flýgur

í hægum hringjum yfir höfði þínu

sest síðan á stein

og heldur áfram að virða þig fyrir sér.[Like a flying bird

flying

in slow circles over your head

then perches on a stone

and continues to observe you.]

Meanwhile the girls are playing in the grass that they planted last year. The words of the poetess are searching birds, and have always been searching birds flying around in the sunshine among seeds and colourful butterflies, “large and almost/uncannily beautiful.” (“stór og næstum/óhugnanlega fögur”.) Still the poem-net is aloft searching for the butterflies of the moment. The words have always been searching birds, whether the poetess felt good, bad, terrible or fantastic, but:

Alla ævi

hef ég samt aðeins

verið að bíða– eftir degi

eins og þessum.[All my life

I have still only

been waiting– for a day

like this.]

It appears to me that the poem-net has managed to catch one of these still yet impatient butterflies.

© úlfhildur dagsdóttir, 2003

Biðröðin framundan (The Queue Ahead)

Read more

Frostið ínni í hauskúpunni (The Frost Inside the Skull)

Read more

Tímasetningar (Timing)

Read more

Laufskálafuglinn

Read more

Hljómorð

Read more

Ljóð í Cold was that Beauty... (Poems in Cold was that Beauty...)

Read more

Háværasta röddin í höfði mínu (The Loudest Voice in my Head)

Read moreLjóðaást (Love of Poetry)

Read more

Tilvistarheppni (Fortune of Being)

Read more