Bio

Sigurður Pálsson was born on July 30, 1948 at the farm Skinnastaðir in North Iceland. He completed primary education in 1963 and graduated from highschool in 1967. He studied french in Toulouse and París from 1967 to 1968 and drama and literature in Sorbonne, first from 1968 to 1973, completing a D.U.E.L.-degree and the firsth part of a Maîtrise-degree in drama studies. He returned to his studies in Sorbonne in 1978 and finished the Maîtrise-degree and a D.E.A. (first part of a doctorial degree) in 1982. At the same time he completed his studies as a film director at the Conservatoire Libre du Cinéma Français.

Sigurður took various jobs over the years. He lectured at the Drama School of Iceland the first three years after its foundation in 1975. He also worked as a foreign correspondent and guide, lecturer at the University of Iceland, and worked on television and film. He devoted the later part of his life to writing and translation. Sigurður was the President of Alliance Française from 1976 to 1978 and the President of the Writers Union of Iceland from 1984 to 1988.

Sigurður was one of the so-called Bad Poets (Listaskáldin vondu), a group of poets that emerged in 1976. Sigurður published many books of poetry, the first of which appeared in 1975, Ljóð vega salt (Poems in Balance). The poetry collection Ljóð námu völd (Poems Mine Power) was nominated for the Nordic Literature Prize in 1993; Sigurður was awarded the Icelandic Literature Prize for the book of recollections Minnisbók (Book of Memory, 2007), having previously been nominated for the books of poetry Ljóðlínuskip (Ship of Poems, 1995) and Ljóðtímaleit (Search For Poetry Time, 2001). Minnisbók was his first book of recollections, followed by Bernskubók (Book of Childhood, 2011) and Táningabók (Book of Teenage, 2014). He has written three novels: Parísarhjól (Pariswheel, 1998), Blái þríhyrningurinn (The Blue Triangle, 2000) and Næturstaður (An Overnight Place, 2002). He also wrote a number of works for the theatre, as well as manuscripts for television and radio and texts for the opera. His books of poetry have been translated into a number of languages, among them Bulgarian and Chinese. In 1994 a bilingual edition of his poetry was published by Editions de la Différence in Paris and in 2014 a collection of his poems in English translation was published under the title Inside Voices, Outside Light.

Sigurður was the City Artist of Reykjavík from 1987 to 1990; he was awarded the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French cultural minister in 1990; and honored with the Chevalier l’Ordre National du Mérite by the President of France in 2008.

Sigurður died on September 19th 2017.

Publisher: JPV-útgáfa

Author photo: Jóhann Páll Valdimarsson.

From the Author

Thoughts about writing

Here, I will try to figure out some things about writing, try to put forward a few questions about the characteristics of this profession in general and also how these things concern me in particular.

Apart from trade and manual labour of different sorts, most jobs more or less involve reading and writing in some way, and are thus in a broad sense writing jobs. With computers, this has become even more common. We now read and write all day long, reading from the screen, writing on the keyboard, we are receivers and senders of messages and for that end use the endless possibilities the system of language gives us, the so called text; to write is to mould, build, piece together a text, to read is to read a meaning from this text. In Latin, text is textus, the same word as weaving, which suits particularly well; a text is exactly a web, a textile of meaning, loosely woven, tightly woven, simple or complex. Furthermore, it is no coincidence that we express many things connected with writing by referring to the discourse of weaving, such as the thread of the story etc. And when it comes to describing a new way of communication, text was close at hand – the new phenomenon was called world wide web, Internet. The Internet, telefax and text messages all contribute to the prominence of writing versus talking. We now write to each other, communicate through written text with other weavers of the world instead of just talking on the phone. Linguistically, talking and writing, these two main language systems, are radically different. They nevertheless constantly affect each other, spoken language for instance often challenges written language in a creative way. The new world wide web is maybe yet another contact area for spoken and written language that will turn out to influence the latter.

But it is not my intention to discuss the whole flow of texts in the world, rather I want to contemplate a few issues regarding the literary text and its creation, and furthermore to focus on the fiction part of literature, but keep aside non fiction texts. It has become a tradition to divide literature into these two fields, fiction and non-fiction that is. But fiction is far from being all of the same genre. Poetry, prose, play, these are the biggest categories; I won’t go into further definitions, subcategories and borderlines, prose-poems etc. The inclination, procedure and method one author uses is not necessarily the same when working in different genres, let alone from one author to another. It is much easier to find the things that are unique or can be contributed to individual authors in literary texts than that which is universal. Most of what characterizes the writing of a literary text is unique rather than universal. Nevertheless, one can point out things that everyone has in common, such as the fact that by writing in a certain language the writer has become part of the whole production of texts in this given language, he has become part of a whole, a link in a chain, part of a tradition, whether he is aware of this or not, no matter if he likes it or not, and it makes no difference whether he is for or against the literary tradition. His work is based on a language system that is part of the common, society, something that is by nature bigger than the individual, in a sense above him – and he, the individual, the writer, is still interpreting the feeling of the individual in this language system that is both his own and the possession of others. Style for instance is in fact nothing else than an individual using this common language system in his personal way; as someone put it: his “eccentricity”, his attempt to not only create a text through the system of language, but to put his creative mark on the system itself.

And as this applies to writing in all languages, one can broaden this assertion about the nature of writing and say that a writer, whatever language he is using, thus becomes an active participant in all text production of the world, from the very start. That story is long and does not only involve humans, for god almighty has in many religions chosen to reveal himself and his will in written language, make himself known in text, come forward as a writer.

What makes writing somewhat special, at least as opposed to other forms of art creation, is the fact that the language system the writer works with, is not only used for literary expression, far from it in fact. The poet works with a common communication system, unlike painters and musicians for example who work with a sign system that is demarcated and not used for anything else. It can be maintained that literary texts, more than other forms of writing and spoken language, use polysemic or multi-meaning-qualities of language, its ambiguity and multiplicity. If we think of a line and put at one end texts that rest on polyphony and at the other those that try to convey one and only one meaning, we can for instance take a simple sentence like: 911 is a general emergency number. This is a sentence that communicates one meaning and we are not supposed to read anything else into it, it can in fact be dangerous to become a creative reader here and see something else in this sentence than exactly what the words say.

On the other hand, a text that stands at the other end of the line, a text that rests on the nature of language that it can communicate the interwoven thoughts of different meanings, create chains of thoughts, point to more than one sense at ones, make use of nuances of meaning, remind of more than one field of reality in the same instance, the most typical of such a text is what we call a poem.

But those who write literature have more in common. They work alone. This is a solitary job, such is its nature. People who cannot stand being alone should find another field to work in, and in fact they do. This is a one man’s job.

We are born alone, die alone and perceive the world alone; the world is in spite of all a personal perception of an individual awareness. But luckily, we can try to communicate it. We build bridges of understanding and misunderstanding to others with language, among other things. But one cannot forget that fiction writing is, in spite of all, a creative job, where an individual mediates an emotion, moulds a personal perception of the world with raw material that is common property, language. In fiction, the unique and the universal come together in one focal point, society and individual. I think all important literature consists of a forceful battle between these two poles. This is creation, a creative vision of an individual, creative work. Creative work, why is that important? Because creative work bears witness to that which is human and the human characteristic of creating one’s fait, creating the world. To create a work of literature is like settling a country, building new laws and rules for a new world, literature is a settlement. And it is important that this creation takes place in language, with the individual expression, the common field of perception is in fact being expanded. In the writing of literature an experimental work involving the possibilities of language is taking place.

Poetry is for example one big laboratory, a laboratory of language that makes this sign system a more qualified tool for everyone, more qualified for expressing yourself, your thoughts and intentions. Intentions that are the first step towards action, lets not forget that.

The work of writing, it’s a one man’s job as I said before, and furthermore the financial ground is unstable. The obvious question is why do people get into this? A general answer, an answer that has to do with the general: people do not get into this, this is a choice as are other things in life, whether the choice is a conscious one or not. Blaming others for getting into this difficult position is futile, this is a choice, no one is asking you to do this job. An answer that has to do with the unique, the individual: the reasons for this choice are totally individualistic. And that leads to posing this question to the one who speaks here: I cannot give any definite answer. I think I was five years old when I answered the classic question, what are you going to become when you grow up thus: I am going to become a jewellery maker, a painter and a writer. I have no clue where this jewellery making came from, I don’t know any jewellers and knew nothing about jewellery. Painters on the other hand were a common topic, my grandfather’s brother on my mother’s side, Þórarinn B. Þorláksson and my uncle Jón Þorleifsson. Here I am in a way assuming that children seek some role models, which of course does not have to be the case. What about the writer? The choice probably rests on various interwoven factors and most of them unconscious ones.

Obviously it is a part of the culture of Icelandic society to view literature as important, we are among the most text-bound nations in the world, the text of our medieval literature is the foundation and innermost core of our existence and identity. No castles, almost no visual images of us having been here for more than a century, nothing but texts from texts to texts about texts. Icelandic landscape: more or less a continuous text, narratives, poems, retorts, place names.

All of this has an effect. Role models: My father of course writing and reading all the time and on Sundays he puts on strange clothes with a collar and sometimes reaches out his hands and hums and then people sing and he talks and everyone listens carefully and I am not allowed to talk or run around. And this man is my father but now he has changed, when he puts on these peculiar clothes he changes and you can not talk to him or go to him. All of this takes place in the church and sometimes everyone is very happy and then he pours water over babies that are smaller than I am and at other times everyone is close to crying and I don’t know why and it ends when a shining box with flowers is carried out and put in a very deep hole in the cemetery. These are strange memories from very early childhood. I have sometimes wondered if this spectacle that children of ministers witness from birth have something to do with so many of them later starting to write for the theatre or being connected to it in some way: Jökull Jakobsson, Oddur Björnsson, Svava Jakobsdóttir, Ingmar Bergman and so on. It so happens that I learnt how to read and write at a young age and soon started to write a lot, why I do not know. This was both fiction and non-fiction, stories on the one hand, never poetry, and on the other hand unbelievably thorough reports and expositions: a diary, weather-book (rather detailed descriptions of the weather from day to day), haying-report, sheep-register and so forth. At times, I was so busy registering life that I had no time to live it.

One could ask: Does age not cure people of this? Luckily, most people I would say. I lost interest in jewellery around the age of twelve, left were painting and writing. The former I tried out when I was fourteen. I had just read the book Lífsþorsti (Lust for Life), about Van Gogh’s life, went to the painting store and bought paint and an easel and painted non stop for three weeks, without much sleep. After that time, it became so painfully clear to me how different the result was from what I had pictured in my mind, that I closed the colour box and gave the painter a rest. The painter in me has yet not returned from that vacation. Of course the method was completely wrong, I meant to catch the fire with a charge. Did not give myself the opportunity to learn the technique step by step. Nevertheless, this was a blow for me and for some time I was completely lost. Had not written anything since I was thirteen and did not find a connection with anything, as is common with teenagers. For a period during my high school years I meant to study psychology, which is said to be common amongst people who deal with some inner problems of their own. We are looking for mirrors more often than we realize.

And then it just happened. Starts with some fiddling as when people learn to smoke; I started feeling my way with poetry, read everything I could get my hands on and before I knew I felt I could put forward something that bore witness to myself in a way that I wanted. Then things evolve and you are caught in the net. But don’t all teenagers write poetry and then come to their senses? Does age not successfully cure people of this? Yes, possibly, but things develop without us always being able to explain them properly. I said earlier that a writer becomes a part of the whole text-community within his or her language. I have to mention that it must be an adventure for each Icelandic writer to take part in the miracle of Icelandic literary culture.

The continuation is linked to what can be said about the financial premises of working as a writer. I have always done various side jobs along writing and started by taking on time- consuming studies after high school. I chose theatre studies and later film studies. I felt that this field was both sufficiently different and similar to writing. Chose to take the exams, even if that demanded energy and time. Finished a Master’s degree and then the first part of a Doctoral degree in theatre studies and a final exam in film directing. France was my chosen country, even if I knew almost no France after high school, but in retrospect I think I was looking for a place that was different enough from Iceland but still within our cultural world.

This has opened opportunities for me in television, film and teaching, among other things, apart from writing. The positive thing about working in the theatre, television and film is that these jobs are in one aspect radically different from writing. You write alone, nothing of worth is done there except by one person, you have to be alone, but in the theatre and when working on films you can not do anything alone, you have to work with others. In that way, one job can provide a valuable rest from the other.

Up until now I have mostly devoted my writing to poetry, plays and translations, although I am preparing some prose work and have for a long time written more of that nature than what I have put forward. Financially, poetry is not anything to rely on, playwriting and translations are somewhat better. Everyone finds the suitable solutions. I have never been a steady employee except for myself, in this one man’s firm, but I have worked in the fields I already mentioned in addition to various projects connected to them, teaching etc. The support of public funds has also been important, and is in fact the prerequisite of somewhat disciplined working habits and provides a minimum security for a given time. Professional writing, as well as other creative work in this country, rests on the support of public as well as private funds. Otherwise, there will be no result, and no real demands can be made. The justification of public funding of the arts is in fact simple: we are investing in creative work, in works of art that the whole nation will own together and will become a part of the common culture.

The questions that the applicants need to be asked are not complicated. There are two of them. First: what is the intention, which work of art is the artist working on, and secondly: what has he or she done so far that makes him likely or unlikely to succeed. Private companies have been hesitant in their support compared to what goes in other countries but I feel this is changing for the better. Enough about that for now.

Lets turn back to the creative work. How does a writer work? Where do ideas come from? The answers to the former questi br>br>br>br>br>n must be individualistic. I have created a kind of flexibility as my basic method. A kind of a combination of regular work and charges, steadfastness and force, the slow approach of an infantry and a terrorist attack.

What about the ideas? Where do they come from? I honestly have to say that I don’t have a clue. Creation in general is such th t it contains some magic that no scientist has been able to explain. Just as physiologists and other scientists have not been able to explain life. It is a mystery. It is furthermore extremely difficult to explain the difference between talent and generousness. Many people have talent, and then there are people like Mozart; obvious geniuses. What on earth is this and where does the difference lay? A mystery.

I have often read and heard people talk about inspiration with scorn, heard sentences like: this is just work, this is 95% work and 5% talent and so on. I still think people should not forget inspiration and should be cautious about ridiculing it. Inspiration, or whatever we want to call it, I do not care about that. Thereby, I am not belittling work, without it nothing happens for sure; inspiration, ideas indeed follow work, “l’appétit vient en mangeant”, appetite is created by eating as the French saying goes.

I have thought quite a lot about the creative work, what it is that happens. I can feel this, envision this as an interplay or conflict between two energies. On the one hand an organizational energy and on the other hand an energy of flow, channel versus flux. One is of no use without the other. You organize a channel, dig it out, but it doesn’t do any good without the fountain, the flow, the river that runs through the channel. In the same way, the flow goes nowhere but into the sand if not for a solid channel. A concept for a work, the basic thought, the structure, all of this makes up the channel. But nothing happens if the flow does not start running. No power plant. No electricity. I think you can learn the channel making of art, the physical aspects such as structural qualities etc. People have been trying to form this, from Aristotle’s to Snorri Sturluson or creative writing teachers who work in American universities. Poeion in Greek means to create and is categorized as a trade. Poesy is derived from this word. You can in other words learn poetics, structural studies, structural engineering, channel making. The other, you sadly can not learn, how to be inspired, how to start the flow from the fountain.

I said before that by writing, the author becomes a participant in the textual community of his or her language and par extension in the textual community of the world. Text is a special phenomenon in the sense that it is accessible in the original form forever and has the possibility of eternal life because it comes alive whenever an individual reader reads it. This quality of the text often creates strange stories of fate. The other day I was for a specific reason renewing my acquaintance with Francis Scott Fitzgerald’s great piece of literature, The Great Gatsby, one of fifty columns that support the temple that holds the heading Novels of the 20th century. In a recent article about Fitzgerald in a French magazine it says that soon before his death in 1940, Fitzgerald received his settlement from his publisher for the year 1939. Seven copies of The Great Gatsby had been sold during the year. Nine copies of the book Tender is the Night. At that time, Fitzgerald was both physically and mentally exhausted, although he was only 44 years old. The settlement from the publisher was hardly uplifting. In this same article you can read that today at least 300 thousand copies of The Great Gatsby are sold every year. For sure it is on reading lists at many universities and it is also discovered by new generations of readers. Texts always have the possibility of eternal life.

In this context I want to end by telling you a story about a publisher. A man is called Jérôme Lindon. He is one of the most respected publishers in France; he has run Editions du Minuit since the start, at the end of the second world war. This is a publisher who’s ideal is the publication of quality literature. From the start, he has published what he feels to be of worth. He for instance published Samuel Beckett from the beginning, in addition to a large number of the authors of the so called new French novel, and many more. He was the first to publish most of these authors, he discovered them, supported them and lost money on them. For a long time, he didn’t loose money on just some titles, but every single title he published. An example: Beckett’s novel, Malone Dies, came out in 1952 and 56 copies sold that year. How could he afford this? It so happened that at the end of the war, at the start of his career, he inherited money from his father and simply put it into his firm. When the inheritance was getting meagre, the books slowly started returning some profit and that flow has been increasing ever since. Thus, he made the inheritance from his father grow manifold. Two of Jérôme Lindon’s author’s have received the Nobel Prize for literature, Claude Simon and Samuel Beckett. Many others have been named repeatedly, such as Alain Robbe-Grillet, Marguerite Duras and Nathalie Sarraute. Lindon once said that fast selling books were good in their own way, best sellers also, but the books he had always had his eye on were long-sellers. Lindon’s wish came true, many of his books are. Beckett’s books alone sell in tens and hundred’s of thousands every year, read in schools around the world as they are. Lindon has not fallen into the temptation of expanding his publishing house. It still holds about the same number of employees as it did at the start. He only adds two or three new authors every year, authors he hopes will become long selling ones over time.

Jérôme Lindon is the only publisher who has stood on the Nobel platform to receive that prize. Samuel Beckett, who does not like the limelight, asked him to take that chalice away from him. And it was appropriate that this literary master got to shake the hand of the Swedish king.

Sigurður Pálsson, 2002.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Travelling Poetry (A Poetic Journey)

I

In a poem named “Næturljóð” (“A Night Poem”) the reader is sent on quite a journey through the night, where entropy reigns and the lights take on strange images, as when the lights of the streetlights change into whipped cream which “flæðir inn í kjamsandi myrkrið” (“flows into the smacking darkness”). Nothing is measured by our perimeters “enda varla nokkuð í veröldinni/á mælikvarða mannsins” (“for there is hardly anything in the world / measured by human perimeters”) and everything is wonderfully alien:

Og eftir hverja slíka nótt

Allir vegir horfnir

Nýtt vegakerfi

Kortin gilda ekki lengurJá ég er að reyna

að segja ykkur þetta(And after each such nigh

All roads have disappeared

A new road-system

The maps do not work anymoreYes I am trying

to tell you about this)

Early in the poem, a brief stop is made at the art of poetry itself when “oddur sjálfblekungs” (“the tip of the fountain pen”) touches “svart yfirborð bleksins” (“the black surface of the ink”), reflecting the black colour of the night and connecting us to the final lines, where the poet is trying to tell us about this! It is this mixture of the high-flown and the mundane that Sigurður Pálsson does so singularly well. After having taken the reader on a dramatic journey without end, a little lofty and certainly confusing, the narrator steps forward and iterates, reminding us that he is trying to tell us something. The reader is pulled back and he can look back over the poetic road he has traveled in content. For this is a poem which is impossible to read only once, it has to be read again, and possibly yet again.

This poem appears in Sigurður’s latest book of poetry, Ljóðtímavagn (Poem-time-chariot) (2003), a book that, according to the poet, is the final one in a 12 book journey through the poem. Ljóðtímavagn is also the last book in a trilogy about the poem-time, or the poem and the time. The first book of that trilogy was called Ljóðtímaskyn (Poem-time-sense) and the next one was Ljóðtímaleit (Poem-time-search), published in 1999 and 2001. Such trilogies have characterized Sigurður’s poetry from the beginning, the first book, Ljóð vega salt (Poems See-Saw) from 1975, was the first book in a trilogy, and now the trilogies are four, making the books 12 as already stated. Apart from poetry, Sigurður is known as a playwright and has furthermore published three novels. In addition to this, Sigurður is a prolific translator, and has introduced many interesting authors to Icelandic readership through his translations, such as Paul Éluard, Jacques Prévert, Albert Camus and Yann Queffélec. Sigurður’s plays are varied in form and scope; many of them are in the style of the theatre of the absurd, with a fantastic streak. Others are, however, more realistic and the same can be said about Sigurður’s novels, they are rather realistic, while being highly symbolic like his plays.

In Sigurður’s first novel, Parísarhjól (Paris Wheel) from 1998, the leitmotif is one of the most famous poems from the Sagas of the Icelanders, “Sonartorrek” (“Lament for my Sons”) by Egill Skallagrímsson. The narrator is an artist who goes to Paris to recover after the sudden death of his twin sister. He has accepted the assignment of illustrating this famous poem and the story then follows his attempt at coming to terms with his loss. The second novel, Blár þríhyrningur (A Blue Triangle) from 2000, depicts the classic love triangle, and the third, Næturstaður (Overnight) from 2002, tells the story of a man who returns back to his home village to attend a funeral after having lived for many years abroad.

In his essay on his own writing here on this website, Sigurður writes about the importance of changing genres, describing it as a kind of a rest and a renewal. And then he describes how he returns back to the poem.

II

The last poem of Ljóðtímavagns is called “Þrisvar fjórir” (“Three Times Four”) and dwells, as so many other poems of the trilogy, on time – the twelve months, which are likened to the apostles.

Fjórar höfuðáttir

Þríeingin ljóðtímans

...

Mánuðir dagar sekúndur

koma kjagandi eftir veginum

með fangið fullt af gjöfumAugu sem hlýða kalli

ljóðtímansLæra að gefa og þiggja

undir fjögur augu(Four directions

The triad of the poemtime

...

Months days seconds

come waddling down the road

with a handful of giftsEyes that obey the call

of poemtimeLearn to give and receive

face to face)

Not much imagination is needed to discern that here the poem is referring to Sigurður’s four trilogies; looking back over the road he has travelled. The poem is a gift which the reader has to learn to give and receive, or is it perhaps the poet himself who has to learn this lesson? If so, Sigurður has learnt it well.

While the books within each trilogy are certainly connected and work best together, each book can also be read by itself and they are in many ways different, as evident from these last three. Certain theme threads themselves through the books, reflections on time is conspicuous, the mirror appears again and again in various disguises and then there are reflections on the poem itself and writing in general. An example of such reflections is the poem “Ljóðlistin” (“The Art of Poetry”), in Ljóðtímaskyn, where the poem is described as being as delicate as the eagle, always about to become extinct, but “samt liggja þarna/blóðugar fjaðrir/út um allt” (“still there are / bloody feathers / lying all around”). According to this poem by Sigurður Pálsson the poem is still a warlike forum for struggle.

I find the strongest part of the book to be the section “Svart-hvítt” (“Black-white”), where the poet draws up compelling images of a landscape which metamorphoses slowly into time as the chapter goes on. This thread is actually traceable to the final poem of the “Söngtíma” (“Songtime”) section, describing the yellow desert-sand and a song about the sunken ship of the desert, the yellow sand is juxtaposed with the black sand of the black land in the poem “Hið svarta land” (“The Black Land”), and it also refers to time in the form of grains of sand in the poem “Sandkorn” (“Grains of Sand”), which is the final poem of the black-and-write section.

These threads of time can be traced back to an early chapter of the book, called “Burt” (“Away”), where everything is on the move, as in the poem “Burt” (“Away”) where everything is immovable, but still seething with repressed motion, for “allt langar burt” (“everything wants to go away”). This slow invisible motion of things, “alls” (“everything”), finds its parallel in glaciers that crawl and moments that enliven and open up, and finally in the imaginary underground train of Iceland, which stops at Perlan. In this poem, as well as in the poems “Óráð” (“Delirium”) and “Tvíeðla” (“Double Nature”) there is an indication of a certain surrealism or absurdism, which I enjoyed very much. The narrator takes the underground train at Perlan, but it does not crawl, the speed is such that the train stops at no stops and the narrator is stuck with a dainty elderly man in a trench coat who recites a long exposition about the difference between this train and the train to Selfoss, which has elegant cabins with old fashioned woodwork. Thus there is not only an imaginary train is Reykjavík, it is also given a story, for it has its past in the old fashioned woodwork cabins.

The poem “Teinar” (“Tracks”) then ends with a highly poetical image of the narrator’s journey on the train from the within a metallic night, “alla leið inn í teinalausan morgun” (“all the way into a trackless morning”), which indicates that the journey is in all and every way uncertain and the road indistinct. This trackless journey then carries me over a whole chapter, back to the poem “Hið svarta land” which also describes road less journeys, now outside the city. The narrator is travelling through the black county when he discovers that there are not roads anymore, neither pats nor sheep-trails and he is startled by the though of having to stay on in the black land. But then soft snow starts to fall and “brátt voru allir vegir færir” (“soon all roads were passable”). The poem could be seen as a kind of a signpost for this book of poetry, it is full of black letters like black sand, and the white snow of the pages makes all roads around the book passable.

This first book in Sigurður’s final trilogy bears witness to how the poet continues to develop his style of poetry and is unafraid to try new roads, even though they are trackless and generally indistinct in the white landscape of poetry. And on the way he might pick up a few bloody feathers, using them as signposts – a much needed one for after this the poet takes off in search of the poem’s time.

III

Ljóðtímaleit starts with three powerful poems called “Ljóðtímaleit I – III” (“Poemtimesearch I – III”). The first poem describes the moment of the morning where time is newborn and everything is unlearned but nothing impossible, the morning is “Opin síða/Líkami sem skynjar/Ljóðtími” (“An open page / A body which senses / Poemtime”). Here we immediately have a reference to the poem itself and the art of poetry, which as already indicated is one of the leitmotifs of the trilogy. In the next poem the poemtime does not pass, it works without having been asked to, “Byggir hús/sem er undarlega samsett/innangengt milli herbergja/sem ekkert sameinar/annað en ljóðtíminn” (“Building a house / which is strangely combined / doors between rooms / which nothing connects / other than poemtime”). Perhaps this is not unlike the structure of Sigurður’s book of poetry, or should I say books of poetry? They also contain doors between rooms in a strangely combined house. The third poem describes how the poem always returns, despite “marmaraþögn” (“marble silence”) and the forgetfulness which moves “stöðugt burt/húsgögn minninganna” (“continually away / the furniture of memory”). Yet again an ancient eternally young novelty appears; “Logandi skrift/á opna síðu//Að nýju hafin ný leit/að ljómandi augnablikum” (“A flaming writing / on an open page // Again a new search started / for lustrous moments”). Still we are in the house of the poet, now furnished with the furniture of memories, and again we are reminded that the poem has its own time and that time is ineluctable.

These poems refer nicely to “Ljóðlistin” in Ljóðtímavagni, where the narrator describes snow which moves in the drift and steaming jets. The movement is stronger than the narrator and it makes him “skrifa allt mögulegt” (“write all kinds of things”) and takes him over: “Núna til dæmis lætur hún mig skrifa://Það jarðbundnasta af öllum skáldskap er líklega ljóðlistin.” (“Now for example it makes me write: // The most down to earth of all fiction is probably the art of poetry.”) The movement in the poem is wonderful, we travel with the snow around the streets, into the narrator’s mind and finally come to this conclusion – which is amusingly inconsistent with much of what I sense in Sigurður’s poetry, while also being a very good description of it.

Sigurður has from the beginning written much prose-poetry and some kinds of drama-poetry, or ‘örstyttur’ (short short-sketches) as he calls it. These proses are very enjoyable and it is obvious that the poet makes the most of the various possibilities of these forms. An example of this is the chapter “Ljósmyndir” (“Photographs”) in Ljóðtímavagn, which is about photographs, and time of course.

The poem “Ljósmyndir” (“Photographs”) describes what influence a photograph has on a wood and a musician, and “úr því talið berst að skógrækt” (“since we are talking about forestry”) the next poem is called “Skógrækt” (“Forestry”) describing how deliberation and enthusiasm must go together, and that this is taught by forestry. Both these ruminations are an example of the speculative style characterising Sigurður’s poetry, which alternates between philosophical ruminations and down-to-earth examples, and Sigurður converges this deftly and humorously. This down-to-earth feel appears for example in the poem “Hótelsalur” (“Hotel saloon”) (I am still in the photograph section), where the narrator is sitting at a hotel which he refused to name for he fears that it will then disappear like all places that have been named in poetry, and now he sits in the hotel saloon, “til alls vís.” (“ready for anything.”) Here we see a highly comical image, as well as an intricate one: speculations on the status of poetry vs. reality, reflect a strange stubbornness, which is almost threatening. The poet has been located at a hotel before, “Hótel vonarinnar” (“The Hotel of Hope”) in Ljóð vega gerð (Poems scale/roads make).

This hotel does not seem to be similarly threatened, through its corridors walks a peculiar group of people, among them poet Grímur Thomsen. Still the narrator is somewhat worried in the VI verse, where those who shy away from the light gather round, and strange happenings occur: “hvergi óhultur/fyrir sjálfum mér h/f” (“nowhere safe / from myself inc.” and the ocean which huddles mumbling at the horizon has now suddenly walked ashore, with all its fishes and sea-monsters, sea-dead and the murdered ones: “ekki senda þetta á land/á mína hugarströnd/ég er bara maður/eitt eintak maður/stöðvaðu strolluna!” (“do not send this ashore / to my mind’s shore / I am only a man / one copy of man / stop the file!”) Fortunately the morning comes: “Morgunninn töltir/á lágfrýsandi fákum ljóssins/um rústir næturinnar//Aftur skal horft í augu spegils/Aftur skal horfst í augu” (“The morning trots / on the lightly snorting horses of light / around the ruins of night // Again looking the mirror in the eye / Again looking in the eye”). Similarly to “Næturljóð” the reader is here taken on a compelling journey into the night, which sometimes is a metaphor for the ocean, in the next verse the “mynni næturfljótsins” (“mouth of the night-river”) is mentioned. However, there is more fear here, the fear of the dark reigns.

The poem is in the final book of Sigurður’s first trilogy, where the poem travels domestic and foreign roads. The first book is called Ljóð vega salt (1975), the next one Ljóð vega menn (Poems scale/roads men) (1980), and the third one, as already stated, Ljóð vega gerð (1982). All these reveal that they are written by someone who lives, or has lived for a long time in foreign parts. The poem scales home and abroad, which is mainly France, Paris, more precisely a few streets and a hotel. Thus it can be said that there is a distinct feel for the city over all the books, sometimes we find ourselves in Reykjavik, “ó mig minnti að þessi borg væri brosandi kona/sem austanvindurinn svæfi hjá/niður eftir laugaveginum og austurstrætinu/og lognaðist útaf á hallærisplaninu framan við moggann” (“oh I thought that this city was a smiling woman / who the eastern wind sleeps with / down the laugarvegur and austurstræti / falling asleep at the hallærisplan in front of mogginn”) or in Paris in the street of master Albert, “ljósmyndastofa hér í bakhúsinu/blasir við hér úr bakgluggunum/þeir taka tíðskuðfatamyndir/ótt og títt/dömurnar skipta um föt og máta önnur/vaðandi naktar um litina/eins og marglita vínberjahrúgu/myndavélar blikka af aðdáun/líma allan pilsaþytinn/opinmynntar á hringlaga innyflin” (“a photographers studio here in the back of the house / visible to me from the rear window / they take fashion-photos / rapidly / the ladies change their clothes and try others on / walking all over naked among the colours / like a colourful pile of grapes / the cameras blink in admiration / glue all the swishing of skirts / open-mouthed on the rounded entrails”). The narrator changes his guise rapidly, he is a student, a reader, a consumer and a buyer, and now the “útsýnið úr bakglugganum” (“view from the rear window”) is quickly changing him into a peeping tom. Both the poems are from Ljóð vega salt. At times the cities merge, as in the chapter on “Þá gömlu frá Hofi” (“The old one from Hof”) in Ljóð vega menn, where the children play paris on the pavement in a French street, “En á Tómasarhaganum/hoppa börnin/börnin hoppa/já já hoppa í parís/á gangstéttinni/á Tómasarhaganum/og kalla efsta reitinn haus//Já já þau hoppa blessuð börnin/í haus/í himinhvolfinu/og eru samt alltaf í parís” (“But in Tómasarhagi / the children jump / jumping children / yes yes jump in paris / on the pavement / at Tómasarhagi / and call the topmost square a head // Yes yes they jump the dear children / in the head / in the heavens / and still they are always in Paris”). Here we also witness another main characteristic of Sigurður’s style, the repetition, which he uses to create rhythm and beat.

IV

The poem itself is always close, in Ljóð vega salt it travels over Sprengisandur: “á sprengisandi ljóðsins hleð ég vörður” (“on sprengisandur of the poem I build cairns”) and in Ljóð vega menn it goes around the country. The chapter or long poem “Á hringvegi ljóðsins” (“On the Poems Circle-road”) is in my opinion simply superb and among the best writings of Sigurður. It refers nicely to “Ljóðtímaleit” and is full of power and speed. (And I recommend reading it all in one, fast, to get a feeling for the journey, in the second round more time can be taken.) The poet addresses the reader: “Skrepptu með mér í ferð út á hringveg ljóðsins” (“Lets pop out for a journey onto the poems circle-road”) and makes it appear quite promising: “Ég skal fara um þig orðum” (“I shall traverse/touch you with words”). The journey’s purpose is to flee the capital, the monotone hype and the consumption, the world-nightmare, which haunts through dreams. In this way the poem is also a call to nature and the narrator shouts: “Niður með samlíkinguna/Lifi myndbreytingin og brauðið/Myndlíkingin myndhvarfið” (“Down with the simile / Long live the transubstantiation and the bread / The likeness and the metaphor”) and it is only now that he understands how similar the lack of rhyme is to nature. The narrator similarly dwells over the crooked trails of the poem in “Ljóðvegagerð” (“Poemscale/roadsmake”), the first chapter of the eponymous book: “Vertu ekki að leita/ljóðveganna á kortinu/Þeir eru ekki kortlagðir/en samt eru þeir og verða” (“Do not search for / the poemroads on the map / They are not mapped / but still they are and will be”).

The poems in this first chapter are generally rather verbal and the language is pungent. The poem “Á hringvegi ljóðsins” actually reminded me of the narrator’s journey with Zombie in Zombíljóðum (Zombie-poems) by Sigfús Bjartmarz, both poems share a criticism on consumption inherent in modern life. So it is easy to see how this would have been a refreshing read after the simple imagery of much of the atom-poetry, although Sigurður certainly makes good use of the symbolism of that type of poetry, so prevalent in the fifties and the sixties. Sigurður’s symbolic world, however, is closer to the absurd, and his poetry is faster – continually on some kind of a restless journey – and contains more of a narrative, as opposed to the still imagery which I always find so characteristic of the atom-poetry. Sigurður Pálsson was one of the ‘listaskáldunum vondu’ (‘the bad poets’ (the reference is to their difference from the acknowledged good poets, and does not at such constitute a valuation of their work), a group of young poets who instigated a considerable enthusiasm for the poem in the seventies and were the forerunners of the wave of poetry following upon punk in the first years of the eighties. Those who have heard Sigurður read his poems, playing with their many nuances, humour, eloquence, criticism and beauty, can easily understand that the audience in Háskólabíó 1976 emerged full of a renewed interest in poetry.

The language has become more simple in the next trilogy, starting with the book Ljóð námu land (Poems settled land) (1985). In his article, “Mörg andlit akasíutrésins: Um ljóðalist Sigurðar Pálssonar” (“Many faces of the acacia: On the poetry of Sigurður Pálsson”), appearing in Skírnir, autumn 1996, Eiríkur Guðmundsson connects this change in language to a certain development through the books: “for the sake of argument it would be most simple to talk about maturity in this context and point out a few rumpus poems of the first book and the more polished poems in the final part of the most recent [Ljóðlínuskip (Poemslineships)1995]” (478). And Eiríkur adds to this that the ideology of the poems grows stronger as the poet moves on. This ideology is many layered according to Eiríkur, while it is perhaps first and foremost the poetry’s desire to make the reader experience the world anew, “to settle persuasively in the mind of the reader and cut in or influence their existence” (489). This is exactly the feeling I have for Sigurður’s poetry and appears for example in the way he piles images upon images, so much so that a kind of a abundance or excess is created, expanding the sensation. And example of this is “Það fjögur” (“It four”) in Ljóð vega menn, starting with the words “Það rifnar ekki nei það gliðnar/Það gliðnar og losnar í sundur” (“It tears not no it widens / It widens and loosens up”), contrary to the “Útblásið traustið/á óbreytileikann!” (“Inflated trust / in unchangeability!”). “Það er saumspretta” (“It is a rip”) and then it is a “lykkjufall/á löturhægri/óstöðvandi ferð” (“ladder / on a very slow / unstoppable journey”). But there is no reason to fear, for “það rifnar ekki” (“it does not tear”), only widens “og losnar í sundur/það losar um undur/og furðuný andsvör/á breyttum andlitum” (“and loosens up / letting wonders loose / and surprisingly new responses / on changed faces”). Again we are swept into a journey with the poem which is certainly not unchangeable, on the contrary, it is continually changing, and in these changes it lets wonders loose and creates completely new answers for the changed face of the reader.

This sensation, which according to Eiríkur is also a kind of illumination, continues to characterize Sigurður’s poetry, as seen in “Næturljóð” quoted in the beginning of this article. Eiríkur himself draws this sensation and illumination nicely out in his own paper given at the launch of the twelfth book.

V

As Eiríkur points out it is easy to see a certain rhythm in the structure of Sigurður’s books. As in the first trilogy the next three books start with long poems describing how the poem literally settles the country and thus might be called some kind of settlement poetry. In the first poem the vista when approaching the country is described: “Ný fjöll og nýjir staðir/Óskrifaðar arkir” (“New mountains and new places / Unwritten pages”); this first part in Ljóð námu menn (Poems settled men) (1988) tells about the authors of the Sagas of the Icelanders. In the third book, Ljóð námu völd (Poems settled power) (1990) the settlement of poetry is placed within a political context. In the poem “Ljóð námu völd” (“Poems settled power”) it is claimed that the weakest voice is the strongest, the voice of the poem, which manages to rise above the ironical laughter of Lenin and the ostentations snigger of the party-priests: “Rödd ljóðsins//einhvers staðar/lengst inni/lengst bakvið” (“The voice of the poem // somewhere / deep inside / deep behind”, but now there is “Nýr hlátur kominn/til sögunnar://hjartanlegur hlátur Havels” (“A new laughter / in the hall: // the hearty laughter of Havel”). The reference here is, of course, the changes in Eastern-Europe during these years.

And the voice of the poem is diverse and this trilogy contains some prose-poetry, in Sigurður’s particularly enjoyable style. In his first book of poetry, Ljóð vega salt, there were some prose-poems which in fact seemed more like short short-plays, in the way they describe a stage and events upon it. In ‘örstytta’ IV, to take an example, a stage is described where books cover all walls: “inn kemur stúlka með gasgrímu með löngum rana framúr og klædd í strigasekk.” (“a girl enters wearing a gasmask with a long trunk, she is dressed in a canvas-sack.”) The girl picks up the books one by one, opening them on page 21 and reads out the first word of the page. She builds herself an igloo and crawls into it, reads from the last book and then knocks the igloo down, from the inside. In Ljóð vega gerð this theatricals are taken even further, the city of Reykjavík has now become the stage, and this theme is revisited in “Nokkrar verklegar æfingar í atburðaskáldskap” (“A few practical exercises in event-fiction”) in Ljóð námu völd. An example of such exercises is to “Fara inn í Reykjavíkur Apótek og biðja um herraklippingu” (“Go into the Reykjavík Apotek and ask for a gentleman’s cut”), and “inn á Aðalpósthúsið í Reykjavík og biðja um tveggja manna herbergi með baði.” (“into the General Post Office and ask for a double room with a bath.”) In the third exercise one should “Ganga inn um aðaldyr Alþingis og biðja þingvörð mjög kurteislega að tala við Lilla klifurmús./Ef þingvörðurinn kannast ekki við neinn með þessu nafni á að spyrja hvort hann sé nýbyrjaður.” (“Walk through the main doors of the Parliament house and ask the guard to talk to Lilli the mouse (a character from a children’s play). / If the guard does not recall anyone by that name then ask him if he is new.”) I sincerely recommend these exercises for all lovers of poetry! It seems to me that Sigurður’s sense of humour is at its best in these prose-poems, and they seem to have their own vision and voice among his poetry. An example of this is “Krossviður” (“Plywood”) in Ljóðlínudans (Poemlinedance) (1993), the first book in the third trilogy. The narrator tells the story of how he choose for his hand craft-course assignment “að saga út Ísland úr krossviði.” (“to saw the outline of Iceland in plywood.”) And then the journey around the country starts, accompanied by broken saw blades and the smell of plywood. The theme of the poemlinedance is of course the line of the poem itself, appearing her to us in a brand new light, and the lines are not only Sigurður’s, he refers to other poets, Beckett and the old friends Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. In the next chapter lines from a pop-lyrics appear. It is in this trilogy that I started getting a real strong feeling for the cohesive structure of all the books. Apart from the already iterated theme about the poem itself, the city is always close, appearing her in a compelling “Miðborgarblús” (“A City Centre Blues”). The chapter “Gluggar og dyr” (“Windows and Doors”) also creates a feeling for a continuity; we have already met with the poem as a house, or the house as a poem in Ljóðtímavagn. The poems come from different directions, in one of them the window frames the view of the narrator, who can not see the ocean, in another it is described how climbing a mountain does not necessarily provide an understanding of mountains, which expand the mind, and on the day that he takes off he walks “um ljósar dyr/Inn í þessi fjöll” (“through light doors / Into these mountains”). Thus the poems are at the same time a window into the world and a doorway which the reader walks through with the poet. Other motifs strengthen with Ljóðlínuskip, where the ocean is the main theme. The ocean has appeared to us in many forms in the poems so far, often as a kind of a threat, and so it is still in this book. Getting lost at sea is a dominant thee, but still the narrator continues sailing over all kinds of oceans and waves. It is perhaps mostly the motion of the ocean which remains with the reader and creates a convergence with the motion of Sigurður’s poetry in general. In the first poem of the long poem, “Að sigla” (“To Sail”), the narrator says that he has watched the ocean for too long:

Ég hef horft of lengi á hafið

Horft þangað til andardrátturinn

Finnur nýtt samræmi

Slagæðarnar skynja svelginn

Ysta sjónarrönd

Skríður stöðugt undan

Eins og kappakstursbratu

Í hægagangiÉg hef horft of lengi á hafið

Til þess að geta skilið

Hreyfingarleysið

EndanleikannLjóðnámuskipið

Á stöðugri siglingu

Í vöku og draumi

Og vökudraumiEn siglingin á sér ekki endilega

Stað

Siglingin er bæði ferð um staði

og staðleysaAð vera

Er að vera á ferð

Samkvæmt lögmálinuOg ferðin er orð og reynsla

Orð

Sem er sjálf ferðin

(I have watched the ocean for too long

Watched until the breath

Finds a new symmetry

The arteries sense the maelstrom

The furthest horizon

Continually crawls away

Like on a racecourse

IdlingI have watched the ocean for too long

To be able to understand

The motionlessness

The finitenessPoemssettledtheship

On a continual sailing

Awake and in dreams

And in waking-dreamsBut the sailing does not necessarily take

Place

The sailing is at the same time a journey around places

and a utopiaTo be

Is to be on the move

According to the lawAnd the journey is word and experience

Word

Which is the journey itself)

Just like the ocean the poem is continually on the move, on a journey, which still seems to be perfectly still. And the poem lives in the body, the arteries which sense it, and it sails through the body whether it wakes or dreams. As before the poem in Sigurður’s description appears like an independent force, a movement which is stronger than the poet, possible even stronger and mightier than anything, like the ocean: difficult to navigate and endlessly varied, as it says in the poem “Tvígengivél” (“Reversibility-engine”). The ocean is a reversibility-engine “að og frá” (“to and fro”), it seems simple but is endlessly varied: “Við sjáum öldurnar hekla/hvíta bekki á vindstrokinn flöt/Sjáum skýin reyna að spegla sig/í öldunum systrum sínum” (“We see the waves crocheting / white linings on the wind caressed surface / See the clouds trying to reflect themselves / in the their sisters the waves”). Ljóðlínuskip is in my opinion one of Sigurður’s best books, particularly for this movement of the reversible-engine which creates a unique rhythm within the poems and between them. This compelling sensation of movement, which is and is not, is also present in the prose-poem “Kirkjuskipið” (“The Nave” (literally the church ship)) in Ljóð námu völd, the narrator is standing in a church and suddenly discovers how the ship is actually moving: “Hægri óstöðvandi siglingu! Ég fann að í raun hafði þessi kirkja aldrei verið kyrr á sínum stað í Île de la Cité í París. Allan þennan óratíma hafði hún verið steinkyrr á ferð. Mikilli ferð.” (“Slow unstoppable sailing! I discovered that in reality this church has never been motionless in its place in Île de la Cité in Paris. All these ages it had been stone still on the move. Moving fast.”) Not only naves and poemships enjoy travelling, in Ljóðlínuspili (Poemlineplay) (1997) the mountains take off:

Þýtt úr þögn

VI

Í nótt var ég að smala

Fjöllunum

Gömlu fjöllunum mínum

SamanLandslagið sem ég kunni utan að

Seigfljótandi á prúðri hreyfinguSmalaði þessum fjöllum

Sem ég hélt að gætu aldrei

HaggastRak þau í rétt

Sem ég kannaðist ekki við

Vissi ekki hvernig

Ég átti að draga þau í dilkaMundi ekki lengur

Hvar þau höfðu verið

Í upphafi(Translated from silence

VI

Tonight I was shepherding

The mountains

My old mountains

TogetherThe landscape that I knew by heart

Semi liquid on a polite moveI shepherded the mountains

Which I thought could never

BudgeShooing them into a fold

Which I did not recognize

Did not know how

To sort themDid not remember anymore

Where they had been

To start with)

The poem contains a strange joy in the midst of the imminent threat, the mountains which are not supposed to budge, are on a polite move, but where and whence? This entire chapter, “Þýtt úr þögn”, is particularly powerful, full of complete stillness together with a singular and pungent feeling for life, death and the landscape of the north. The snow bank hanging quietly over our existence is immovably waiting, the ice fields have shifted and the night is either white as sail or a dark stream.

The mountains are of course the representative of the country, the oceans opposite, but still they are joined in this movement. Ljóðlínuskip also contains some trees, as if to balance against all the water, and the trees continue to grow in Ljóðlínudans. This offers a beautiful motion, and trees grow in the imagery of pages and leaves, shooting their roots in heaven as in earth. The tree is a symbol of man, or the woman, as it says in the third poem, where it connects heaven and earth like the giant-tree of the legends, and simultaneously an image is printed of a complicated webbing of roots and branches at either end of the trunk, standing out against the sky and the earth like outlines, or lines of poetry. Thus Sigurður continues to play his lines of poetry, lying in a tight web across the three books of the poem line-group.

V

Certain lines have been traced through the oeuvre of Sigurður Pálsson, but this does not mean that the roads of his poems are exhausted. The books all offer some of the best the poem can offer, a new perception, even illumination, humour and seriousness, together with dreams and nightmares. I have briefly mentioned how the poet refers to other poets and works of fiction, but have not discussed the connection to worlds of legends, though such examples are numerous, whether direct and symbolic. And so I can only advice the reader to embark as soon as possible into the “Hafvillur” (“Oceanic Strays”) (Ljóðlínuskip) of Sigurður’s poetry, enjoying being “nafnlaus og standa í brúnni/Í kyndiklefanum undir þiljum/er nafni minn að störfum/Hvorugur veit að hann er vofa hins” (nameless and standing at the helm / In the engine room below ships / my namesake is working / Neither knows he is a ghost of the other”). Thus the reader is the narrator’s ghost and vice verse, the navigator cannot find the way home, the home harbour has grown indistinct in the memory “Hafi hún einhvern tíma verið til” (“Assuming it ever existed”). The navigators of the poems (such as myself) can only navigate into more astrays:

Æ við héldum einu sinni

að vegleysur sjávarins

væru endanlegar þrátt fyrir allt

Staðfræði geimsins og heimsins

yrði lýstSíðan hefur óendanleikinn

stöðugt verið að birtast

Iðandi sýnir

stjörnukíkisins

Sundlandi sýnir

smásjánna kjarnaofnanna

undirdjúpannaÞyngdarlögmálið

virkar ekki lengur í eina átt(Ah, we once thought

that the tracklessness of the ocean

were final despite all

The topography of space and the world

would be describedSince then the infinity

has appeared continually

Whirling visions

of the telescope

Vertigo visions

of the microscope the nuclear reactors

the oceanic depthsThe law of gravity

does not work in one direction anymore)

úlfhildur dagsdóttir

Articles

Articles

Friðrik Rafnsson: “En ny balance : Sigurður Pálsson : humoristisk og dybsindig lyriker = A new balance : Sigurður Pálsson : A humorous and profound poet”

Nordisk litteratur 1994, pp. 12-3.

Jón Yngvi Jóhannsson: “Three Times Four Makes Twelve: Sigurður Pálsson´s Gospel of Poetry in Twelve Books”

Nordisk litteratur 1994.

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 488, 489, 492, 495, 578

Awards

2017 – The May Star, the Writers‘ Union of Iceland and the National and University Library poetry prize: Ljóð muna rödd (Poetry Remembers Voice)

2016 – The Knight's Cross of the Icelandic Order of the Falcon, for his contribution to Icelandic literature and culture

2016 – The Jónas Hallgrímsson Award

2009 - Gríman, the Icelandic Theatre Award: Utan gátta (Play of the year)

2009 - Gríman, the Icelandic Theatre Award: Utan gátta (Playwrite of the year)

2008 - Chevalier de l´Ordre du Mérite: For his valuable contribution to introducing French culture in Iceland

2007 - The Icelandic Literary Prize: Minnisbók

1999 - The National Broadcasting Service´s Writer´s Prize

1990 - Named Chavelier de l´Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (A Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters) by the French government.

1987-1990 - Reykjavík City Artist

Nominations

2017 – The Icelandic Translators‘ Award: Uppljómanir & Árstíð í helvíti (Illuminations & Une saison en enfer) by Arthur Rimbaud (with Sölvi Björn Sigurðsson)

2016 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Ljóð muna rödd (Poetry Remembers Voice)

2001 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Ljóðtímaleit

1995 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Ljóðlínuskip

1994 - The Nordic Council´s Literary Prize: Ljóð námu völd

Ljóð muna rödd (Poetry Remembers Voice)

Read more

Segulsvið (Magnetic Field)

Read more

Táningabók

Read more

Inside Voices, Outside Light

Read more

Blinda konan og þjónninn (The Blind Woman and the Waiter)

Read more

Ljóð í leiðinni: skáld um Reykjavík (Poetry to Go: Poets on Reykjavík)

Read more

Ljóðtímasafn (Poetry Time Collection)

Read more

Force de la poésie et autres poèmes

Read more

Ljóðorkulind (Poetry Energy Source)

Read more

Ummyndanir skáldsins og fleiri ljóð (The Poet‘s Metamorphoses and other poems)

Read more

Svo þú villist ekki í hverfinu hérna (Pour que tu ne te perdes pas dans le quartier)

Read more

HHhH

Read more

Líf annarra en mín (D’autres vies que la mienne)

Read more

Allt til að vera hamingjusöm (All That´s Required for Happiness)

Read moreLíf mitt með Mozart (My Life With Mozart)

Read moreErró í tímaröð: líf hans og list (Chronological Erró: His Life and Art)

Read more

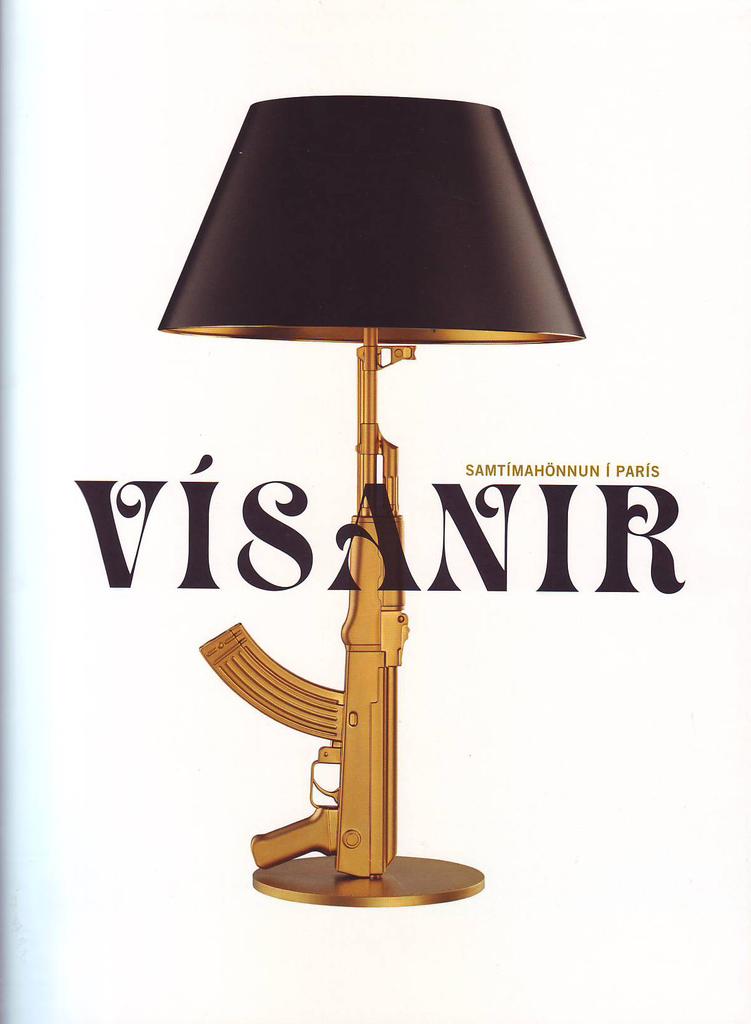

Vísanir : samtímahönnun í París (References: Modern Design in Paris)

Read more

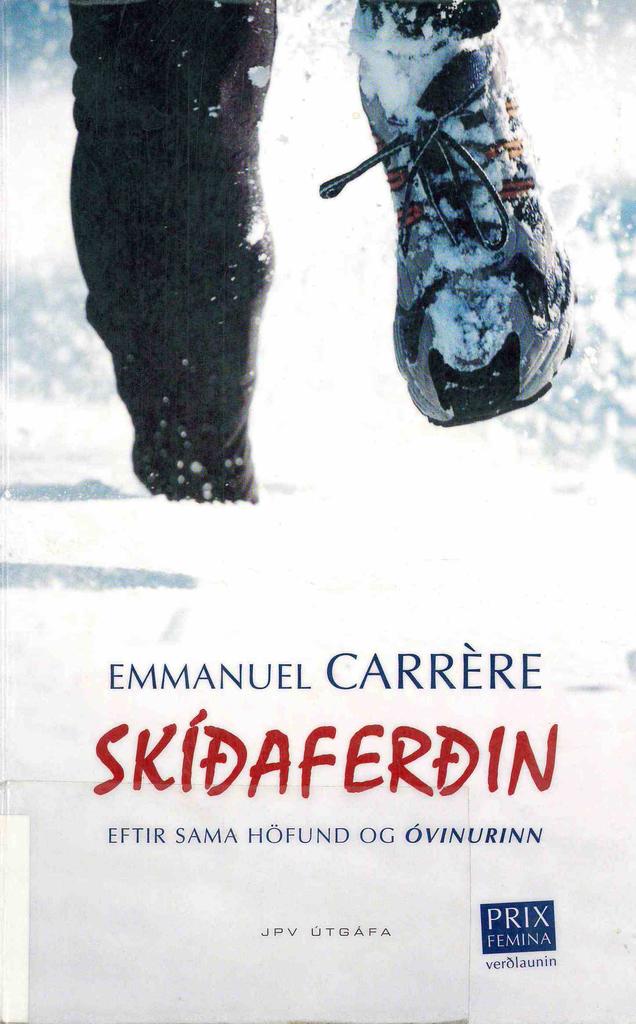

Skíðaferðin (The Ski Trip)

Read more