Bio

Sindri Freysson was born on the 23rd of July in 1970. He studied philosophy and comparative literature as the University of Iceland. He has worked as a journalist, mostly at Morgunblaðið newspaper.

Sindri’s first book of poetry, Fljótið sofandi konur (Float Sleeping Women), appeared in 1992. Since then he has published works of all kind: a short story collection, novels, other books of poetry and a children’s book. He has also written plays for the University Theatre. Sindri has published articles and fiction in various periodicals, newspapers and magazines. His novel, Augun í bænum (Eyes in the Town), received the Halldór Laxness Literature Prize in 1998. His second book of poetry, Harði kjarninn (The Hard Core) was nominated for the Icelandic Literature Prize in 2000. In 2009, Sindri sent forward two works, the poetry book Ljóðveldið Ísland, dedicated to the history of Iceland from it’s independence in 1944 until after the economic collapse in 2008, and the novel Dóttir mæðra minna (The Daughter of My Mothers), which takes place during World War II. His book of poetry Í klóm dalalæðunnar (Prisoner of the Ground-Mist) won Reykjavík City’s Poetry Prize, the Tómas Guðmundsson Prize, in 2011. Sindri’s latest work to date is the poetry book Góðir farþegar (Good Passengers) from 2015.

Sindri Freysson lives in Reykjavík.

Publisher: Veröld / Svarta forlag.

From the Author

A few memos on writing A – G

A. I get hooked by ideas and images but when they have contaminated the blood almost entirely, I flush them out into text. Not that I see the process in some sublime light, the flaws are too many. And luckily, there is no cause-effect law between a sudden idea and a finished story. (Talking about flaws in form: unconscious formal flaws of some books have given them more life than the long time spent that others bear witness of).

B. I think all builders of texts tell the same story about their constructions. Incoherent pieces from their consciousness and experience end up in the cement they stir in the molds, often without them being aware of it. This is similar to you finding a hand or an ear on your balcony after the big explosion on the ground floor, discovering that these very parts are missing from your own body.

C. We scatter words in the earth at the border of two adjacent worlds. Worlds we have built around our own selves from piles of memories, defense mechanisms, hidings and bullshit. Only, the gap between these cheap, but scary buildings, our worlds, is somewhat untarnished. Is that the right word?

D. My whole imagination is saturated with eroticism. That’s how simple it is, and still not. Eroticism within, that also colors the way I look at reality without. Every word, every movement, every image, I see in an erotic light. Everything has an erotic veil and deserves to be seen with bare eyes as such. In other times I would have been accused of a pornographic view. That is in fact the main problem; to draw a line between the pornographic and the aesthetic eroticism, which can with a few wrong decisions when it comes to wording, become crude, mechanical and coarse – if the whip is not used right.

E. The words our grandfathers and grandmothers and their grandfathers and grandmothers used to describe beauty which is still in front of us sound false and pretentious today. Now we try not to sound highflown and are thus speechless against nature. Dumbfounded and strangely uneasy in our minds, for nature man thought he had tamed by words is not to be controlled, as horrific examples bear witness of. Our vocabulary has not renewed itself as fast as nature does, being at the same time the same as it was before.

F. When bookstores have piled up the book and put a prize tag on it, I can no longer control characters and events. I have to seek control elsewhere. This carries with it both a relieve and a feeling of emptiness, for as they say: “the thrilling thing about power gained without effort, is how easily you lose it again.”

G. When people stop getting entangled in meaning and to stumble over understanding, they feel what words have to give. They become like a raised picture under your fingertips. What the mind reads when the eyes have been closed is often a much truer image than what the dull and critical eyes see.

Sindri Freysson, 2001.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

“A map drawn by blind men”: on the works of Sindri Freysson

The eighties were a particularly lively time for poetry in Iceland. Interest in poetry was high and poetry readings became fashionable among young people, with a little help from the surrealist Medusa-group and the more traditional The Poem’s Best Friend. Young people – and people of all ages actually – published their own books or booklets of poetry, and sold them at cafés in a kind of a bohemian style; these books were often original in design and separated themselves clearly from the publication of the publishing houses. Such a colourful self-publication had of course been popular before, it traces its roots at least back to the modernist movement at the beginning of the twentieth century. In Russia, for example, many books of poetry were published as a part of the avant-garde, often characterised by a conjunction of pictures and texts. The punk-style invigorated the poem; not only did the ideology of self-publication sit well with punk, young people’s poems also became an excellent outlet for the anarchism and subversion of this rather undefined movement. This beautiful coalition between poetry and punk perhaps found its clearest expression in the poetess Didda, who at the beginning of the nineties wrote texts for bands like Vonbrigði (Disappointment) and Sogblettir (Hickies), but did not publish a book of poetry until 1995.

Sindri Freysson was born in 1970 and grew up in this atmosphere. He was quite young when his poems appeared in newspapers and magazines and he published his first book of poetry, Fljótið sofandi konur (Float Sleeping Women/The River Sleeping Women), in 1992. The book was published by publishing house Forlagið and was in many ways different from the style of poetry that was typical of the eighties. The language is elevated, the poems are highly symbolic and characterised by opulence and fantasy. The book shows many indications of being the product of a young poet, for the elevated style gives the poetry a youthful air. This youthfulness does not depict anger or angst as often seen in the poetry of the eighties, Sindri’s poetry is strangely distant, despite the intense feelings that the language indicates, and the reader starts to think that the narrator is somehow standing outside his own struggle. This can clearly be seen in the poem “Stiginn af himni” (The Staircase from the Sky):

Í flughöfn

bíða svartbrýnd örlög

við vegg þeirra

er heima sátu

Bálkestirnir grænu

handan við gestaglerið

munu brenna með mér

lengi

Ber ekkert tollskylt

annað en efann[In an airport

black browed fate waits

by the wall of those

who stayed at home

The green pyres

on the other side of the guest-window

will burn with me

for a long time

Do not carry anything to declare

except doubt]

Despite the dramatic separation described in the poem, it appears rather cold and analytical, it is almost as if the strong vocabulary is restraining the feeling rather than passing it on. Still, there are poems that are more quiet and at the same time more intimate, like “Leikur” (Game), where the narrator opens up “the soft/half-moon” (mjúka/hálfmánann) and: “Read[s] the hum of veins/with [his] lips” (Les æðaþyt/með vörunum), “Darkseeking animals/tread secret paths//This will not be told/to anyone else” (Myrkfara dýr/þræða launstigu//Þetta verður ekki/sagt öðrum).

At times the verbosity drowns the poem and the world of symbolism becomes unintelligible as in the poem “Yfirlit fimbulljóða” (An Overview of Wintry Poetry), where a man is lying face down “among disused toys/and wolfeaten books” (innan um aflóga leikföng/og vargétnar bækur) and his seaweed-brown skin “is reminiscent of the wooden autumn” (minnir á trénað haustið).

The poem ends with the lines: “The sun’s begging trip/cancelled” (Betliferð sólar/aflýst), which do little to help the reader to visualise the image.

However, there are many enjoyable images such as in the poem “Í gegnum spegilbrotið” (Through the mirror fragment), where the “night-peace is broken by/rhythmic knocks from outside/like from a ticking/heart of the house/or somebody with a sledgehammer/intends to visit/a neighbour” (Næturfriðurinn rofinn af/taktföstum höggum að utan/líkt og tifi/hjarta hússins/eða einhver með sleggju/hyggist heimsækja/nágranna). Loneliness here takes on an unexpected image, when the heartbeat of the sleepless narrator is possibly transformed into an overeager guest of the neighbour.

The image could also be a ghostly image, for the window is broken and the house thus clearly in a state of disrepair – and the narrator himself could be the ghost, or the ghost is the guest who is seen in the mirror, when the face is outside “the broken window”? He must be one or the other, because “If memory does not betray me/I am the only one awake, as before”. (Svíki ekki minnið/vaki ég einn sem fyrr).

The poem “Lestarslys” (Traincrash) also offers up an interesting trail of thoughts. Outside the glass there are “screaming trains/ghosts of other journeys” (öskrandi lestir/vofur annarra ferða) and on the way into the tunnel the narrator dreams of “the fast/rotation of earth/and finally the eruption of steel/towards the sun” (hraðan/snúning jarðar/og seinast stálgosið/mót sólinni). Still, we do not know who is alive and who not, and even the journeys have ghosts, and the accident itself is possibly just a dream. The image of speed is effective at the same time as the glass, like the mirror fragment earlier, underlines the distance of the narrator.

This ghostlike atmosphere characterises the poems in Fljótið sofandi konur. The narrator is frequently located in otherworldly places, or travelling between worlds. To some extent one might say that this ambience is influenced by poet Gyrðir Elíasson and his haunted poetry. At least the poem “Halaminningar” (Memories from Hali), dedicated to Gyrðir, indicates such an influence. This poem is more fluid than many of the others and it is also light and bright, despite unexpected phenomenon appearing, such as the stuffed paw on the shark-beach and the dark-eyed ghost, who, after a closer look, turns out to live in a cup of coffee. Coffee is a common theme in Gyrðir’s writings. The narrator here leans towards tea, it is more wholesome after all – and thus Sindri stresses his independence from his genius, as well as acknowledging him.

The short story collection Ósýnilegar sögur (Invisible Stories) was published in 1993 and carries many symptoms of the poetry. The language continues to be elevated and highly flavoured, fantasy is prevalent and as before a strange distance marks the text. Some of the stories, like “Náðarstund”, “Dagbók hringjarans”, “Horfna stafrófið” and “Vargaklukkan” (A Moment of Grace; Diary of the Bell Ringer; The Lost Alphabet and the Clock of Wolfs) are pure fantasies. “A Moment of Grace” describes a sailor’s last visit to his wife, followed by the man with the sickle who has the last word: “This is a nasty business”. (16) Despite the dramatic tone of the story, there is also a distinct sense of humour that marks many of the stories.

“The Diary of the Bell Ringer” is a highly amusing story about a bell ringer in a little fishing village who is very preoccupied with his fellow bell ringer from Notre Dame. He considers Quasimodo to be his ideal and finds the bell of his country church too insignificant, so he decides to invest – with the aid of the congregation fund – in a more appropriate bell. Its powers are such that at its first strike the church and village collapse, along with the villagers’ hearing, rocks fall from mountains and a tidal wave breaks boats into pieces.

The more realistic stories, like “Í sunnudagsspegli”, “Lyklavöld” and “Kryppan” (In a Sunday Mirror; Keys and The Hump) are also marked by fantasy and mysticism, for example when the hung over husband in “In a Sunday Mirror” sees his mirror image put its hands to its head, flaying it of flesh and skin. In the stories “The Lost Alphabet” and “Game” (“Spil”) the author reflects on the nature of fiction. The first is dedicated to Jorge Luis Borges and like some of his stories it focuses on mysterious books and the power of language. The narrator who says he can trace his family roots back to Sæmundur the Wise (a famous magician and priest in Icelandic folktales), describes an alphabet that another of his forefather has allegedly found. This alphabet, or these runes, have the nature “that if they are placed beside a poem”, in any language or any form, “the poem immediately becomes transparent to the reader”. The narrator adds that this sounds better than it actually is, for the letters “shear the poem of all its mysticism and make it an obvious and simplified reading as if it were a bibliography or rules of sport.” (66)

Later he describes his relative’s journey home, with the runes in his pocket, coveted by the crew members who thought them something precious, jewels or diamonds, but nobody “imagined a key that could turn Völuspá into a monotonous row of words and The Divine Comedy into a chatty travelogue, for men usually do not think of poetry as valuables.” (70)

Here one might imagine that the author is a little to preoccupied with the mysteries of poetic language, and wishes to elevate his own often opaque style, but the sense of humour that saturates the story is bound to raise some doubt with the reader. That doubt is confirmed in the story “Game”, where the main character is reading a book he had taken randomly from a shelf. At first he likes the book as it extols the mystery of poetry: “To write is to hide, and leave it to seekers, the blood-hounds, to read the clues.” (112) But on the last page a comment by the publisher appears: “You have just finished reading Sindri F’s book, Invisible Stories”. When the book is finished the stories will disappear, if this is not a forgery. In some cases a new story might appear. The character is very irritated by this and complains about empty wit and lack of originality that hollows out “some of these men, like moles.” (120) With this the mystery of poetry and fiction is somewhat lessened, while not done away with, for the story ends with the amusing practice of the character to glue pieces from a puzzle onto people’s clothes, when walking the streets: “The piece is easily attached to the small of the back of a tunic-clad woman, almost disappearing in the pattern, Nökkvi could not see it as the woman walked on, but the next one separated itself from the greyish suit like a crevasse in the material. Still there were nearly five hundred pieces in his pocket. This puzzle would hardly become a whole picture.” (121)

Sindri’s first novel, Augun í bænum (Eyes in the Town) (1998), was published five years after the short story collection. The book indicates that some time has passed and that during this time the author’s approach – and possibly his thoughts on poetic language – has changed. The novel describes how the gossips of a small town can ruin people’s lives. The main protagonist is a young doctor who falls in love with the wife of the local fishery-king, they have a short relationship, which he then ends by travelling abroad for further studies. However, he cannot forget the woman and thus returns back to the town and the relationship starts again, with dramatic results.

Sindri manages quite well to build up the ambience of persecution and isolation in a dying fishing village, where most people are dependent on the dole and the rest work at servicing them. At the same time he weaves social realism into his story by describing the general deterioration of the countryside, in addition to a short history of economics with regular inputs about the run-up and eventual collapse of the Co-operative. The name of this bygone company is of course very symbolic for the burned out and ill-fated relationships described in the novel: the fishery-king’s marriage is empty, while the relationship between the protagonist and the wife seems to be hopeless. The symbolism can then be continued in the name of the woman, who is named Sólveig, nicknamed Sól (sun), but this symbolism is also marked with some irony.

As in the short stories there is a certain consciousness about the text’s status within the literary discourse. At the beginning of the book there is some discussion on writing a novel, where the narrator announces his lack of interest in such undertaking, while also experiencing a need to write down his story in his mother’s half-written recipe-book. The narrator addresses his reader, and seems to have a certain reader in mind, but the story is partly a kind of a crime novel. In the beginning the imminent death of a woman is referred to, and in the final part it comes to light that not only the woman, Sól, has been shot with a shotgun, but that her husband has disappeared – and the narrator is being blamed for both incidents.

Sindri received the Laxness Literary Award for the novel, which is in many ways different from his short stories in style and approach, while the text is still characterised by the implied author’s distance from his subject. It is clear that the author is ambitious for his novel, and even though the middle chapter, describing the separation and the narrator’s stay in Reykjavík and Sweden, is a bit dullish, it can also be said that this dullness reflects to some extent the boredom that the narrator feels from a series of one-night-stands with women. Sindri is at his best in creating and sustaining the small town ambience, appearing at times driven by a kind of a pervertism due to the relentless spying on other people’s lives, the eyes that are watching at windows, looking in or out of them. The small town ambience is also to some extent fantastic, especially as concerns the extraordinary manner of the narrator’s parents death and the even more extraordinary exploits of the doctor who is the narrators predecessor. Thus the first part of the book is well structured, where the stormy youth of the narrator is described, his moving away out of town and later his medical studies, bringing him back to his old home town where he meets Sól. When he returns to town after staying abroad, the story picks up pace again, and becomes quite compelling when the dramatic events start to pile up at the end. This visualisation of the village creates a tangible feeling for space, giving the novel a clear frame and this is its greatest strength.

In a certain way Sindri’s first book for children, Hundaeyjan (The Island of Dogs) (2000), illustrated by Halla Sólveig Þorgeirsdóttir, is also characterised by a certain isolation and confinement. It describes how dogs dream of an island far out in the ocean where they can be free, and do not need to be dependent on people and their questionable caprices. The story is originally written for Sindri’s daughter and is a very fine little tale, partly due to Halla Sólveig’s illustrations.

As already said the poetry books of the eighties were often of an original design, mirroring the imagination of the publisher, the poet him/herself. Such a game of looks was not present in Sindri Freysson’s first book of poetry, as it was designed in the much more traditional form of poetry published by publishing houses. In the short story collection some innovation in design is apparent, where a black page faces the title page of each new story. In the poetry collection Harði kjarninn, eða njósnir um eigið líf (The Hard Core: or, spying on ones own life) (1999) this interplay between surface and content, form and subject is taken much further, as the design of the book is quite original and the configuration of the poems is different from what the reader has come to expect. The book is broader than books of poetry tend to be and an enlarged fragment of a photograph of the author appears on the cover. A similar enlarged fragment of the same photograph separates the three chapters of the book. In synchronisation to this cutout of the picture, cut-outs from the poems appear on the left side of the spread, like a refrain, while the whole poem is situated on the right. This emphasis on look and style has not been noticeable in the design of Icelandic books, possibly due to the idea that it is only the content that matters.

However, while we can accept that the content is the most important part of the book, this is not to say that its appearance does not matter at all, for a competent and well thought out design of a book can often imply much about it, and give a message about everything from the intention of the author to the publisher’s opinion of the work. Thus the successful design of Harði kjarninn is illustrative of the change that has occurred in Sindri’s writing. The fragments of the photograph and the floating lines of poetry, as well as the subtitle, njósnir um eigið líf, underline the intimate thread that lies through the book, many of the poems are personal, particularly the poems in the second part, “einkavegur” (private road). This intimacy indicates that Sindri is not afraid to take on new roads in his poetry. This book is considerably different from his earlier poetry, similarly to how Augun í bænum is different from his earlier prose writings.

The photo-fragments and the poem-fragments also mirror the form of the poem itself, as an enlarged fragment from a life, or a moment, and thus iterate how the poem is always a kind of a fragment in itself. The poems in Harði kjarninn are somewhat marked by this fragmentation, and this is fully in alignment with the book as a whole, characterised by travels and fragments of images from cities, train stations, trains and cafés, where “a blind man is walking between/tables and offers travelling lamps/blind sells light/I think but buy/nothing in the growing twilight” (blindur maður gengur milli/borða og býður ferðalampa/blindur selur ljós/hugsa ég en kaupi/ekkert í vaxandi húminu). The poem “blindur maður” (a blind man) illustrates well how Sindri captures moments like these, simple and clearly demarcated, and stills them for a moment before they rush by.

In the poem “flutningar” (moving) the wandering spirit of the book can be seen to crystallise. It describes an incomplete move from one house to another for “after the moving the pictures seem/like blurred in a distance/They take a long time being ordered on the walls/The furniture still acts like/the old place is its home” (eftir flutningana eru myndirnar/eins og óskýrar í fjarska/Þær eru lengi að raðast á veggina/Húsgögnin þykjast enn/eiga heima á gamla staðnum). The furniture is personified and has its own opinions on matters, while the narrator himself has “moved/whole-heartedly” (fluttur/af heilum hug). All but his dreams, “they cling to the new tenant/who does not get much sleep/the first nights”. (Þeir hjúfra sig að nýja leigjandanum/sem sefur lítið/fyrstu næturnar).

This poem refers to another poem about the painter Stefán from Möðrudalur and his painting that always tilts at night, “like the mountain is tilting its/head or the sunset behind it/is heavier on one side of the sky”. (eins og fjallið halli undir/flatt eða sólarlagið að baki því/sé þyngra öðrum megin himins). The objects in the house still come to life, for the house is full of stories that the four weak wheels of the newspaper-cart can never carry, as it says in the poem “fjögur veikburða hjól” (four weak wheels). This poem describes two paper-route-queens that are responsible for seven thousand pages of small type and grainy pictures. Again this image reflects the design of the book itself, the page opposite is in fact grey like the house in question, which is ash-grey.

Moving and travels then all end in a nameless concluding poem describing a journey over a cold desolate sand. The bus is full of “dead people, talking about/inexpensive developing/poisoned fast-food/maps drawn by blind men” (dánu fólki, að tala/um ódýra framköllun/eitraða skyndibita/landakort sem blindir menn teikna). “The driver has though/for years/about the shortest way”. (Bílstjórinn hefur brætt með sér/árum saman/stystu leiðina)

Sindri Freysson’s earlier work rarely invited the reader to take the shortest way, but these new poems are accessible and interesting at the same time, the verbosity has given way to a more pointed imagery and the distance has given way to “whole-heartedness”.

© Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, 2003.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 499

Awards

2011 - The Tómas Guðmundsson Literature Prize (Reykjavík City Poetry Prize): Í klóm dalalæðunnar (Prisoner of the Ground-Mist)

1998 – The Halldór Laxness Literature Prize: Augun í bænum (Eyes in Town; novel)

Nominations

2013 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Blindhríð (Snowstorm)

1999 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Harði kjarninn (Hard-Core; poetry book)

Góðir farþegar (Dear Passengers)

Read more

Blindhríð (Snowstorm)

Read more

Í klóm dalalæðunnar (Prisoner of the Ground-Mist)

Read more

Dóttir mæðra minna

Read more

Ljóðveldið Ísland (The Poetry State of Iceland)

Read more

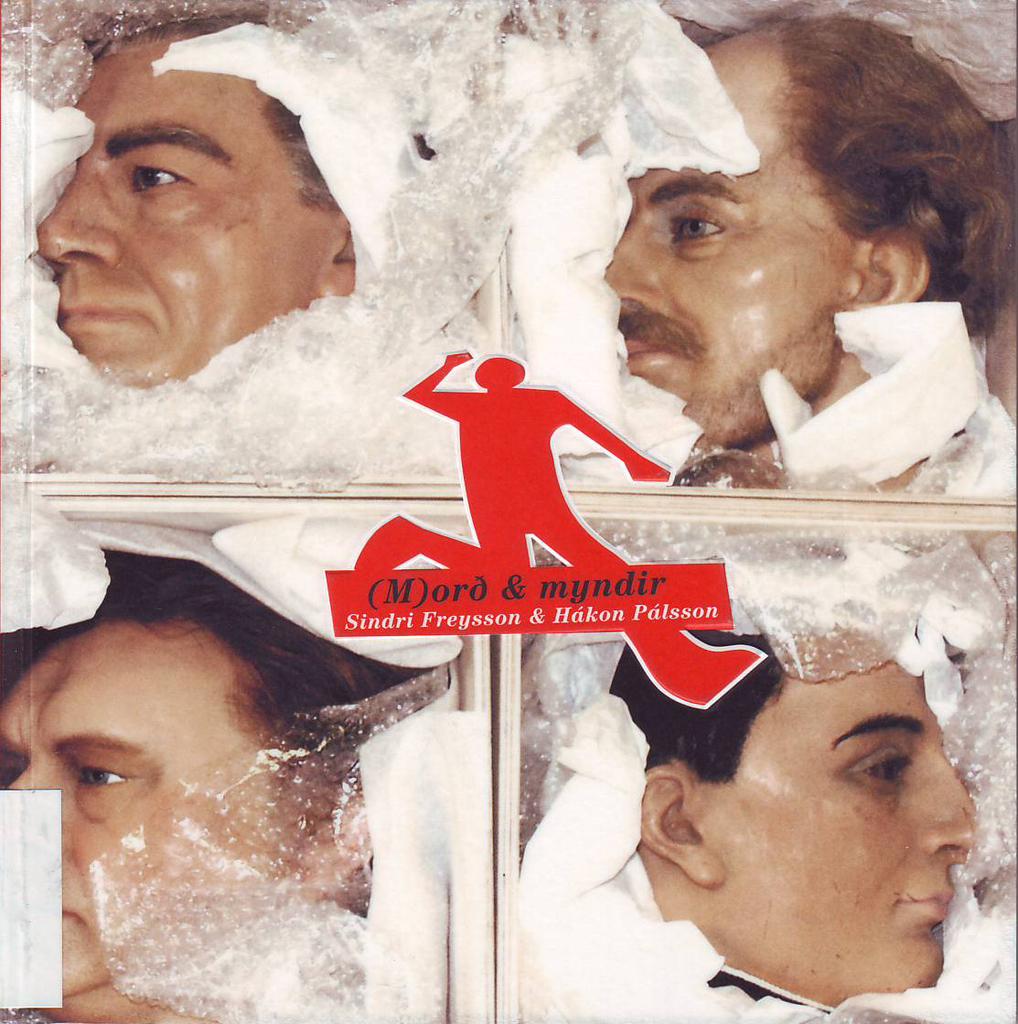

(M)orð og myndir (Words/Murders and Pictures)

Read more

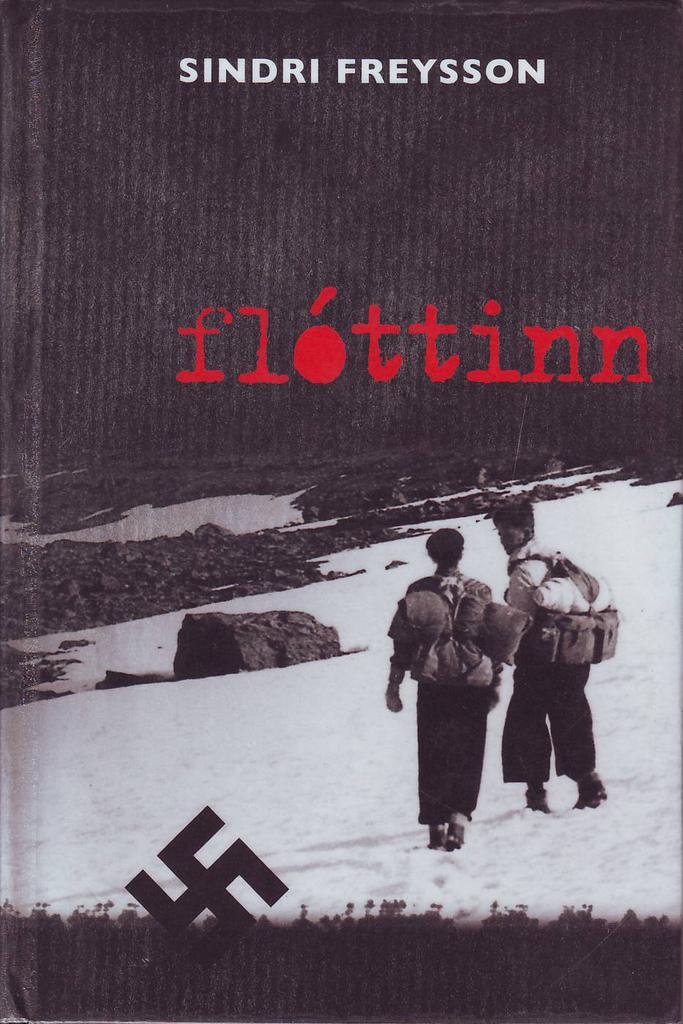

Flóttinn (The Escape)

Read more

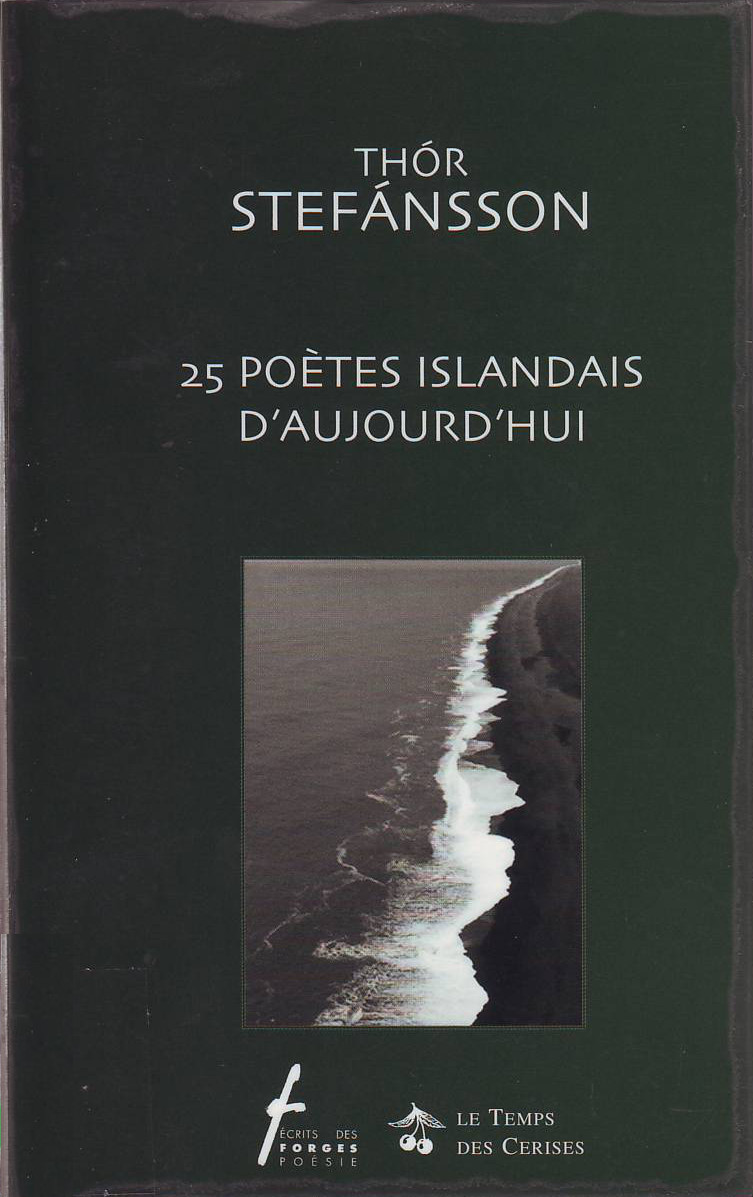

Poems in í 25 poètes islandais d´aujourd´hui

Read moreSaga án fyrirheits : Framhaldssaga TMM (A story with out a promise : Continued story TMM)

Read more