Bio

Þórarinn Eldjárn was born in Reykjavík on August 22 1949. He studied literature and philosophy at the University of Lund in Sweden between 1969 and 1972, Icelandic at the University of Iceland 1972-1973, and completed a phil.cand. degree in literature at the University of Lund in 1975. Þórarinn lived in Stockholm from 1975 to 1979 and spent a year in Canterbury in 1988-1989.

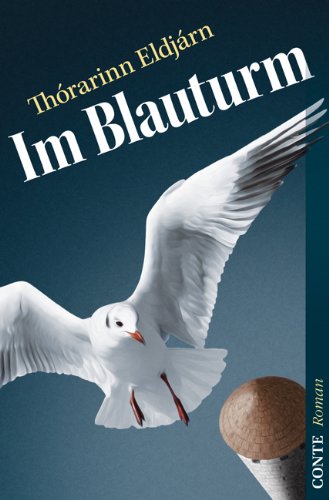

Since 1975 Þórarinn has worked as a writer and translator. He has published a number of poetry collections, short-story collections and novels as well a translating fiction for adults and children from English and the Scandinavian languages. Together with his sister, the artist Sigrún Eldjárn, Þórarinn has published a number of poetry books for children, and many of them have received various awards. Þórarinn’s fiction has been translated to other languages, his novel Brotahöfuð (The Blue Tower) has appeared in several languages, including English and French and was nominated to the Nordic Council Literature Price in 1999 and the IMPAC Dublin award in 2001.

In 1998 Þórarinn received The Jónas Hallgrímsson Award for his contribution to the Icelandic language and in 2008 he was the Reykjavik City Artist. In 2013 he achieved a Special recognition by the Swedish Academy for the advancement of Swedish culture.

From the Author

The Author on the Author

This sounded like stuttering rhyme or the start of a conjugation example, a masculine noun with a definite article: The Author on the Author... But the idea seems to be that I explain why I write. And as always, I immediately feel that I need to apologize. To answer in court. Defend myself. Point out mitigating circumstances, ideally involving something unspeakably deep and unique and grand. This is often the case when it comes to work of artistic nature: A calling, an inner need, a unique vision, conviction, expression and suffering, I was bursting at the seams with something that no one else had to offer...

It is probably best if I pick one of those things to elaborate on...

At this moment Jóhannes Kjarval, of all men, appears like a liberating angel: Out of the radio sounds an old interview. Vilhjálmur Þ. Gíslason is trying out a brand new recording gramophone, talking to Kjarval on his fiftieth birthday, and asks him in a very serious tone why he paints. And Kjarval replies in a deep voice that reaches out from the past through the buzz and the crackle:

- Painting carries a great deal of responsibility, BUT, WHEN IT COMES TO IT, YOU PAINT BECAUSE YOU ARE A PAINTER.

Then after a moment’s thought he adds:

- But perhaps I ought to have become something else...

I may not be a Kjarval, but I am past fifty and therefore I feel fully entitled to put it like he does: I write because I am a writer. It is as simple as that. Perhaps I also ought to have been something else. But the decisive element in this line of work as in any other is most likely always some combination of interest, coincidence, nature, ability, inclination, luck, bad luck, vanity, ambition. Chance, glance, bending, safe landing …

To name a few things.

Can I also mention a love of creating and compulsion?

Þórarinn Eldjárn, 2001.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

About the Author

Transmitting Life To Us: On the Fiction of Þórarinn Eldjárn

Þórarinn Eldjárn’s writing talent was already evident in his college days. Along with two of his schoolmates he started a popular radio show, “Radio Matilda”, which satirized current issues. Since then, the Matilda gang have been prominent each in their own fields – the other two are the politician Davíð Oddsson and the film director Hrafn Gunnlaugsson. One legacy of the Matilda era is the play Ég vil auðga mitt land (I Wish to Enrich My Country), which was co-written by the threesome under the nom de plume Þórður Breiðfjörð and opened at the Icelandic National Theatre in 1974.

Þórarinn began his writing career when he returned home after studying in Sweden in 1975, and has since been a prolific writer. He has written many books of poetry, short stories, novels and plays, as well as having translated a great deal of fiction.

Poems

Þórarinn published his first book, Kvæði (Poems), in 1974. It immediately became very popular and the book was reprinted a few times due to high sales. The poems are all in verse and epic, that is have alliteration and rhyme like traditional Icelandic poetry. This poetic style was almost unheard of among young poets at the time. Many who disliked free verse applauded this and thought Þórarinn´s book heralded a return to previous poetry forms. The poems owed their popularity not least to a curious humorousness which is expressed in an unusual register, but the language is easily understood. They are a mixture of traditional poetic language, a variety of old words, contemporary everyday language, slang and word play: “He dressed the wounds of the tortured tramp / for success” (“Drottinn drottinn“ (“God, God“)). Sometimes he uses modern language about a familiar subject or old poetic language about the present time. He also juxtaposes old and new material, filling his poems with allusions. Familiar characters are shown in an unexpected light, for instance Grettir and Tarzan, Hansel and Gretel and Sveinbjörn Egilsson, and sometimes his interpretation of them is ironic. This is a familiar device called “burlesque”, in which serious issues are turned into comedy or vice versa and inconsistencies in material and style are played around with.

This method has since been applied by Þórarinn many times, especially in his second book, Disneyrímur (Disney Rhymes) in 1978, which satirized the American cartoonist Walt Disney. In the poems, Þórarinn uses some of the meters of ancient oral poetry form “rímur” (“rhymes”), but the subject matter of the poems is today’s mass culture and consumerism. There are six poems in total and most of them have about 60 verses. The humour in this hilarious epic poem is further amplified by the fact that the ancient poetry form is not used in the traditional way, to praise a hero or a heroic deed, but to show an unscrupulous tycoon who stops at nothing to make a profit, even at the expense of his co-workers, after his American dream has become a reality. Here is the 38th verse of the sixth poem:

Nemur löndin Andrés önd,

argvítugur steggur.

Dauða hönd á dal og strönd

disneyvélin leggur.[Colonizer Donald Duck,

daft little drake.

Its dead hand on dale and shore

the Disney machine lays.]

Erindi (Verses), the third book of poems is in most ways similar to Kvæði. It also contains quite a large collection of well known characters from various moments in history. Many of the poems are epic and some of them are long and allusive. Unexpected references abound, and they can be quite entertaining in a fresh context, as in the poem about Ari fróði: “- What turns out to be truer we shall prefer / if neither is true”. There are also poems which contain meditations and observation about people, often peppered with nasty satire and word play, as for instance in “Minnimáttarerindi“ (“Inferiority Verse“):

Hafin yfir allan grun

er þín fræga klausa.

Ég hef eðlisávísun

innistæðulausa.[Above all suspicion

is your famous clause.

My reality check

is overdrawn.]

In Ydd (Sharpened, 1984) his fourth book of poems, Þórarinn has decided to abandon metre in his verse. The poems are generally more concise than in his previous books, more personal, emotional, and thoughts and reality are processed more thoroughly. The style is more polished than before, words are no longer used as filler to complete the rhythm or aid the rhyme. The humour is still as potent as ever and sarcastic remonstrations are common. These poems show that Þórarinn is as confident expressing himself in this form as in metered verse. In the book there are also a few prose poems which show more imagination and introspective expression than his other poems.

Seven years went by before the publication of Þórarinn’s next book of poems. It was entitled Hin háfleyga moldvarpa (The Lofty Mole), the poems are mostly unmetered like in Ydd and even more visual and richer in wordplay and humour. The poem entitled “Tillaga um handhægt ferðasett handa póetískum flóttamönnum“ (“A Suggestion for a Compact Travel Kit for Poetical Refugees“) is a fine example of this. There are references to Ingólfur Arnarson (a political refugee and Iceland’s first settler) but in the poem the columns Ingólfur made drift to land from his ship (in order to decide where in Iceland to settle) become “medium-range missiles which blast off / into the unknown / in the hope of finding a beach of wonders”. The same year, in 1991, his sixth book of poems, Ort (Composed) came out; it contains only metered verse, including nine sonnets.

Þórarinn’s poems are often portraits of daily life and environment from all historical periods, often shown in an unexpected light, which is sometimes humorous but usually powerful. He often succeeds at combining an acute visual sense and an original use of language with a clever twist. “Even angels sometimes seem to put their wings wrong” he says in the poem “För“ (“Tracks“) about wandering off the path of righteousness, the compass is ruined, as the alcohol that floats the magnet has been drunk, and the “Needle points to hard south / and that is where you came from” (Moldvarpan). The poems range widely in time and space, and the old and the new is sometimes linked through references to the cultural heritage. “Staðarskáli er Ísland“ (“Staðarskáli is Iceland“) (Ort), describes this well known rest stop, and the poem ends like this:

Hér vil ég una ævi minnar daga

innst í skoti bíða veitinganna

átekta og halla mímishöfði

hógvær undir flatt og nema allt þetta.[Here I wish to while away the days of my life

deep in a corner awaiting the food

leaning my wisdom head

modestly to the side studying]

The poems are not all mock-epic, they are sometimes about mentality and ruminations but these are usually expressed through images which are witty at times. Two subject matters which have been among the most consistent with poets of all times very rarely occur in Þórarinn’s poetry: love and nature. Still, “Ljóðabréf úr sveitinni“ (“A Poem Letter from the Country“) contains an unabashed declaration of love, although it is neither very heartfelt nor expressed in loving similes. Here are the last two verses:

Æ skal ég vera þér

lóðbolti í tin

þér diskur í drif

deig þér í skál.Ég vil leka því til þín

hvað ég elska þig

og kinoka mér við

að kynoka þig[To you forever I shall be

soldering iron in tin

disc in drive

dough in your bowl.I want to leak it to you

how I love you

I shy away from

shoving you]

Many environmental descriptions are unique and memorable, especially of the cityscape, but the poems are not concerned with communicating nature images, as there is perhaps enough of that on offer from elsewhere. Þórarinn writes a few poems which contain peculiar images of weather, changes in light and the planets, but all perception of natural phenomena is tied up in the existence and viewpoint of the urbanite.

Þórarinn’s next three poetry books are in many ways superior to the previous ones. The poems are more pointed, both in thought and structure, the concerns are more honest, the poetic language more elegant, there is a stronger visual sense and a compression of material and form strengthens the structure.

Þórarinn has written a number of poems for children which appeared in the books Óðfluga (Madfly, 1991), Heimskringla (World Ring, 1992), Litarím (Colour Rhyme, 1992) and Halastjarna (Comet, 1997), all of which contain illustrations by Sigrún Eldjárn. Þórarinn is the only Icelandic poet living today who has involved himself in this particular area of poetry, which has been almost universally shunned by other poets since Stefán Jónsson passed away. These children’s poems have been well received, they are quite entertaining and have proved useful in stimulating the development of speech in children. The poems are not written in a childish or watered-down language, but the words reach children’s ears because the use of words is clear and the material is made interesting with humour and fun. The illustrations also play a big part in directing the attention towards the text. Some of the poems are based on common figures of speech which are clarified and given new life by weaving a little story around them. All the poems are metered, there is plenty of play with rhyme, a style which suits young children well, especially those who are still illiterate and have to be read aloud to. Þórarinn’s method in the children’s poems partly consists of personifying both animals and objects and the language itself. He applies this in a humorous way to the sensibilities of children, who haven’t had an extensive experience of reality yet. “Frakkinn“ (“The Overcoat“) is the title of one little poem:

Frakkinn minn er fótalaus,

fótalaus með engan haus.

Hann kemst ekki heim til sín,

hann kemst ekki neitt án mín.

Þó er hann á þönum út um bæinn,

en þykir best að hanga allan daginn.[ [Literally:]

My overcoat is legless,

legless without a head.

He can’t find his way back home,

he can’t go anywhere without me.

Still, he keeps running all over town,

when all he really wants to do is to hang around all day.]

Short stories

Þórarinn’s stories, both short stories and novels, have his definite style and are reminiscent of his poems. Many of the motifs come from ancient sagas, but become a part of modern reality and are closely tied to it. The language is usually elegant and clear and the style is a curious mixture of ancient words and modern language. There are many references, both to ancient literature and new. The narrative method is usually realistic, the storyteller usually pretends to be an impartial observer, the characters are clearly defined in their everyday routine. Some of the short stories are set in Reykjavík, with landmarks referred to by their proper names, such as streets, companies and institutions. The narrative style remains the same even when incidents and characters which go beyond the realm of reality are being described. Most of the stories communicate considerable material in a concise form; the narratives move fast and are sometimes sketchy, the plots are clear and grotesque at the same time and often hilarious. Humour and irony dominate the style and are often brought out in unexpected final twists.

Þórarinn has published four short story collections, the first one, Ofsögum sagt (Tall Tales Told), in 1981. Some of the short stories are spun around an absurd idea which nonetheless takes root and starts to seem almost normal in the context of the narrative, and becomes a powerful source of tension in the story. For these kinds of stories old motifs from the sagas, folk belief and folklore and religion provide the perfect subject matter. Þórarinn makes clever use of these, for instance in the stories Tilbury (Tilbury), Mál er að mæla (Time to Speak Now), Lúlli og leiðarhnoðað (Lúlli and the guide), Arnsúgur (Arndraft), Lifað (Lived) and Eftir spennufallið (After the pressure-drop). The risk with absurd stories is that the absurd elements get too ridiculous, become superficial and lose their magic, but this hardly ever happens with Þórarinn’s stories.

Quite a few of the stories contain a sarcastic criticism of tiresome modern ailments, such as greed, snobbery, vanity, the pursuit of self-interest and the thirst for attention. The mockery is crystallized in careful characterization and the laughable fate of the characters, for instance in the stories Lagerinn og allt (The Stock and All), Opinskánandi (Openly Improving), Í draumi sérhvers manns (In Every Man’s Dream), Síðasta rannsóknaræfingin (The Last Colloquium) and Saga Svefnflokksins (The Sleep Squad Story).

Many of the stories are about daily life and problems and memories from childhood and the teenage years. Such stories have many elements in common with Þórarinn’s first books of poetry. Some of them describe peculiar accidents in people’s daily lives, where many far out things happen and unexpected situation come up, sometimes with dark humour, as in the stories Dund (Pottering), Áhrínið (The Onslaught), Klámhundurinn (The Porn Fiend), Eigandinn (The Owner), Tvær litlar konur (Two Little Ladies), Í svip (At a Glance), Ókvæða við (Adversely), Töskumálin (The Bag Situation) and Níðstöng (Shame Pole).

The story Önsa (Önsa) is a good example of how the stories tend to open up fresh perspectives, make one doubt the legitimacy of predominant views, deliver a nudge to habitual thought, make serious matters funny and funny matters serious. An official representative of the historical farms project, who is supposed to document place names and get farmers to clear away rubbish, discovers that all is not what it seems. He abandons the project and instead becomes a pioneer in the tourism project “Save the classic Icelandic rubbish farm“. A romance develops between him and a farmer’s daughter at Hlíð in Ódalur, Ansa Önundardóttir. This story has connections to the novel Skuggabox (Shadow Box), about the very same historic farm and the pioneer who lived there, Önundur breadfoot (foot of the hill), and his offspring. Other short stories by Þórarinn are connected to this novel and many of them are connected to one another, and in various ways to some of his poems, especially the names of characters and places.

Novels

Þórarinn’s first novel is called Kyrr kjör (In Peace); it came out in 1983 and tells of the life of the poet Guðmundur Bergþórsson who lived in the17th century. He was handicapped and lived in dismal circumstances, but his gift for poetry gave him the strength to become and independent person, a kind of a professional writer, in a society characterized by poverty, lack of education and the abuse of power. The handicapped poet manages in his own way to overcome all this with his poetry, cleverness and by using weaknesses of powerful men to his advantage. Folklore and folk beliefs play a large role here. Guðmundur is a folklore character himself; even in his decrepit state he possesses a weapon which many feel threatened by – the art of poetry. He is a power-poet and knows how to trip people up through magic. Yet, he longs to be healthy and free and is convinced that the dwarf Pálmi Purkólín owns some ointments which will do the trick. He never manages to obtain these, but Guðmundur’s ability to travel increases considerably when the giant of a man Þóroddur, a branded thief, becomes Guðmundur’s personal carrier, and Guðmundur repays the favour by protecting him from the sheriff. Guðmundur’s friend, Trout-Björn, also comes out of the world of folklore, and was known among other things for his dealings with elves. Þórarinn uses these stories and various folklore for his work and these three are the core characters in the story. Compared to and in their dealings with these three, the members of the ruling class, secular and religious, as well as the merchant seem both vain and laughable.

Among Þórarinn’s novels, Skuggabox (Shadowbox, 1988) is furthest from a traditional narrative. It has elements of modernism with its multi-layered storyline and fragmented narrative, broken timeline, vague distinctions between characters and a lively imagination. The point of view varies and the narrative alters between the third and the first person. The story is modern, yet tightly attached to an ancient, national story tradition. It begins at the family farm Hlíð í Ódal, where a bread boy is born in a supernatural way, so that the family may continue to prosper. A member of the well known Kjögx family then begins to tell his story and members of this family appear in other stories by Þórarinn. Kort Kjögx is the son of Bragi Kjögx, a hapless poet who is also the main character of the short story “Ókvæða við“. On his maternal side he is a member of the Nepp family; a particular trait of theirs is an unstoppable laughter when they get angry. Further clues point to Þorleifur Repp, the famous linguist, academic and eccentric who lived in the first half of the nineteenth century. The epithets which are hurled at Kort in his nightmare: “Abeat scurra!” are for instance reminiscent of Þorleifur’s expulsion from a magisterial exam in Copenhagen in 1826. Kort goes to study in Sweden, intending to become a “speech behavioural theorist”. He collects data for his final thesis but never writes it; he suffers from a discovery compulsion which is entirely directed at absurdity. Kort’s departure from Sweden and the trip back to Iceland are comedic variations on the folklore about Sæmundur the Wise escaping from Sorbonne and riding across the ocean on the back of a seal. When he reaches the shore, Kort knocks the seal unconscious with the hard drive from the computer. The second half of the novel tells of this failed academic after his return to Iceland. He inherits a house from his uncle, meets his relatives and acquaintances, continues his useless inventions and behavioural studies, and attends a Kjögx family reunion. This is all accompanied by stories and incidents, some are strange and folklore-like and they often ridicule various Icelandic national pastimes, like genealogical research.

Þórarinn’s third novel, Brotahöfuð (The Blue Tower, 1996) features real historical characters, like Kyrr kjör, and is based on a few historical facts. This is the story of the strange life of Guðmundur Andrésson of Bjarg in Miðfjörður, who lived in the 17th century; he came from a poor family but was educated with the help of a neighbour, Arngrímur the Learned. Guðmundur proved to be an industrious and intelligent student and graduated with honours from the school at Hólar and among other things, the novel tells of his experience at Hólar and the school life there. When the story begins, Guðmundur has become a prisoner in the notorious Blue Tower dungeon in Copenhagen, where he was sent for demonstrating against Stóridómur [i.e. Great Judgment, a very harsh law regarding sexual conduct – trans]. In prison he reflects back on his life and tries to make sense of his fate. He has brought with him to prison one book; The Golden Ass or Metamorphoses by Lucius Apuleius, and as he gradually traces the metamorphoses and trials of the hero he finds parallels in his own life. The reader learns that already in his school days, Guðmundur was met with hostility from the aristocratic bishop Þorlákur Skúlason and from some of his schoolmates who were the sons of wealthy farmers and officials. After a distinguished student career at Hólar, Guðmundur becomes deacon at Reynistaður, under the protection of his friend, Reverend Einar Arnfinnsson, who had been his schoolmate at Hólar. Their friendship and their partying are given much room in the story. Einar is forced to leave his post after breaking his wow of chastity, and Guðmundur is thrown out with him. After this he has no more hope of becoming a reverend, his enemies see to that. Guðmundur was a man of many talents and tried his hand at many professions, including trading; he was an excellent writer, poetic and eloquent. He was a difficult man, expressed his opinions bluntly, let no one tell him what to do, and could be sarcastic and libellous. Many people felt the sting of his words, among them bishop Þorlákur. After his expulsion from Reynistaðir he turned to drink and subsequently his detractors managed to seize his writings where he objected to Stóridómur. His bravery did not go unpunished, since his enemies had been waiting for an opportunity to bring him down. He was arrested without trial and immediately sent to the Blue Tower.

The novel is an interesting description of a historical era and 17th century society. The characterization of Guðmundur is clear and memorable. This rebel is brought vividly to life, and the reader empathizes with him as s/he follows the unusual life story of this man who refused to accept oppression and violence quietly. The author manages to link Guðmundur’s life and work to many well known contemporaries of his, such as Björn of Skarðsá, Jón the Learned, Jón the Indies Traveller, Þorleifur Kortsson and Hallgrímur Pétursson, as he had some dealings with all of them. One of the strangest incidents in the novel is true, that Guðmundur fell down from Blue Tower but did not attempt to flee. Eventually he was released from this notorious prison with the help of Ole Worm and with his support began a new chapter of his life in Copenhagen. At last he found himself in circumstances which suited him: he became a scholar and demonstrated that he was a talented scientist. This novel by Þórarinn was nominated for the European Aristeion Prize in 1998 and selected one of the five best books that year (the English translation by Bernard Scudder). The Blue Tower is the only Icelandic work of literature which has received that honour. All of Þórarinn’s novels are composed with a sparkling narrative joy and a good sense of humour, although there is always an underlying seriousness.

Þórarinn Eldjárn has written some non-fictional works, like the book Ég man (I Remember) which contains flashes of memory and Veðurdagar (Weather Days), facts and fiction about the weather, which he co-wrote with his wife, Unnur Ólafsdóttir. Þórarinn has also been a proliferate translator. He has translated many novels, mainly by Nordic authors, as the following list demonstrates, including three novels by Göran Tunström and Inferno by August Strindberg. He has also translated many poems and song lyrics for plays and other theatre works. He has rewritten Völuspá (The Sybil’s Prophecy) into modern Icelandic, keeping the ancient poetry form of the original poem in the revised version.

Þórarinn has overseen the publication of two works by his father, Kristján Eldjárn former President of Iceland, after his death. The books are Arngrímur málari (Arngrímur the Painter, 1983) and Kuml og haugfé (Graves and Burial Treasures, 2000).

The Life in Fiction

The short story Forvarsla (Restoration) in Ofsögum sagt describes the conversations of people inside Sigfús Guðmundsson’s repair shop, Foreskin Inc. He repairs books, paintings, magazines, toys and craft items. In the novel Skuggabox Kort Kjögx rushes through the door of Foreskin after the seal has carried him to Iceland and there he finds Fúsi (in fact his name is Vigfús in the novel) still mending Lillý the doll, like in the short story. In the repair shop, acquaintances from all corners of society meet, discuss the mystery of life and tell stories. This is a kind of a story factory or caldron for Þórarinn Eldjárn’s fiction. Peculiar characters, weird experiences, strange misfortunes, incredible incidents, can all be found in the repair shop of the conservator who is constantly slaving away at his conservation work and is also a wise man in debates. Human frailty is also revealed in its many forms: we see the vanity and shortcomings of ourselves and our fellow citizens and society as a whole in a comically elevated, sometimes sad light; historic phenomena are suddenly shown from a fresh angle. All this blossoms in Þórarinn’s writing, whatever form it takes. Here Doctor Jón Árnason tells the story of when he ended up dancing with the elves on New Year’s Eve. There Kort Kjögx presents his contraction theory which Kolli Mix sums up in the mantra “Life is a spring”. It is, however, disputed whether people travel from the outermost end of the spring to the innermost end or vice versa. Fúsi the conservator tears up an old copy of the newspaper Morgunblaðið because the news reporting is lousy. He says that life always passes such media by. They don’t show us “real life, the one with the big L” he says.

It is, of course, the role of fiction to communicate Life to us.

© Eysteinn Þorvaldsson.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Articles

Articles

Bergþórsdóttir, Kolbrún: “Samtal med Þórarinn Eldjárn : NT-Intervjun”

Nordisk tidskrift för vetenskap, konst och industri. 2010, vol. 86(1), p. 55-60

Holownia, Olga: ‘‘The provocation is titillating.’’

Barnboken, 2012-11, Vol.35

Markelova, Olga: “Poetry of Þórarinn Eldjárn”

Vestnik Pravoslavnogo Svi͡a︡to-Tikhonovskogo gumanitarnogo universiteta. 3, Filologii͡a, 2019-12, Vol.58, p.111-122

Markelova, Olga: Potato crisps for squirrel Ratatosk and hiking equipment for the first settler Ingólfur. Reception of old icelandic culture in poems by Þórarinn Eldjárn”

Vestnik Pravoslavnogo Svi͡a︡to-Tikhonovskogo gumanitarnogo universiteta. 3, Filologii͡a, 2019-12, Vol.60, p.45-56

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 193, 440, 463, 489, 490, 495, 606

Steinberg, Sybil S.: "The Blue Tower"

The Publishers weekly, 1999, Vol.246 (36), p.81

Willson, Kendra J.: “Þórarinn Eldjárn (1949- )” Icelandic Writers.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 293, ed. Patrick J. Stevens, Detroit, Gale 2004, pp. 356-366

Awards

2020 - Sögusteinn – IBBY Iceland’s Children’s Literature Prize, together with Sigrún Eldjárn

2020 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards : Translation of Hver vill hugga krílið? (Who Will Console the Tiny?) by Tove Jansson

2018 -. Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Ljóðpundari (Poetry Pounder) (As the best children’s book of the year)

2014 – The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Veiða vind (Catching Wind) (as best translated children’s book of the year)

2013 - Sögusteinn – IBBY Iceland’s Children’s Literature Prize

2013 – Special recognition by the Swedish Academy for the advancement of Swedish culture.

2010 – Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Árstíðirnar (Seasons) (As the best children’s book of the year)

2008 – Reykjavik City Artist

2007 – Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Gælur, fælur og þvælur (As the best children’s book of the year)

2006 – The Guðmundur Böðvarsson Poetry Award

2005 – Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Hættur og mörk (As the best poetry book of the year)

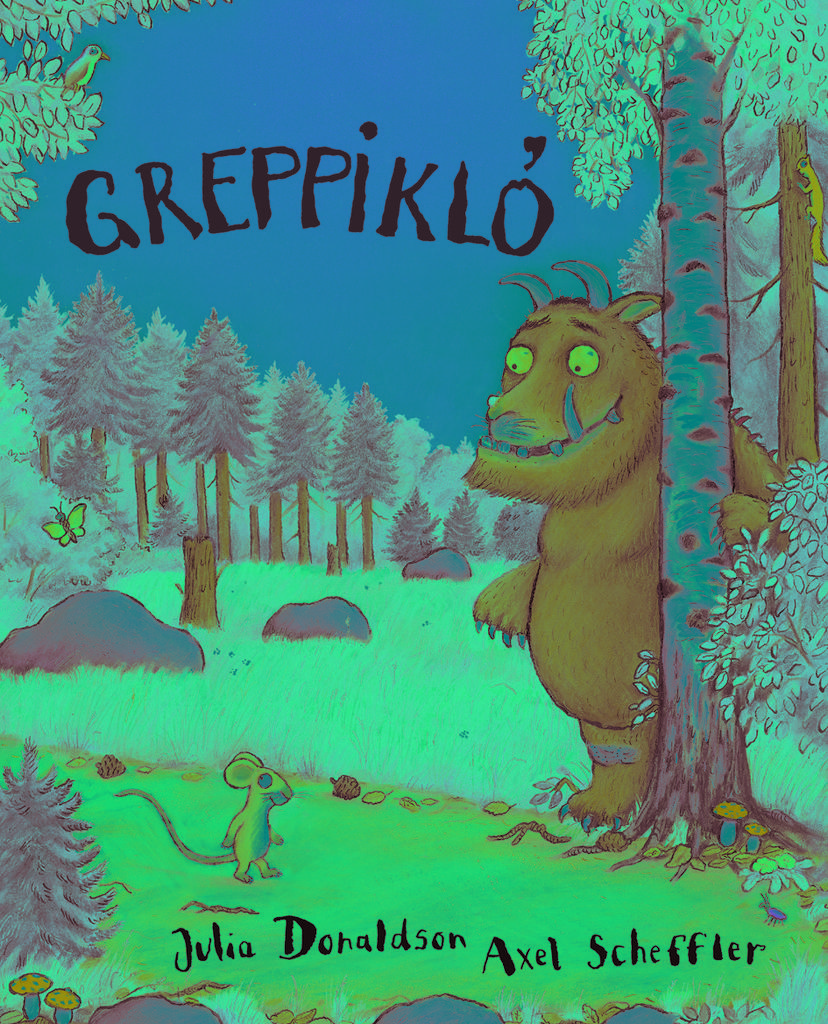

2004 – The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Greppikló (The Gruffalo) by Julia Donaldson (For translation)

2001 – IBBY Iceland Award: For his writings for children

2001 – Icelandic Bookseller’s Award

1998 – The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Halastjarna (Comet)

1998 – The Jónas Hallgrímsson Award

1993 – IBBY Iceland Award: For his writings for children

1992 – The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Óðfluga (Fastfly)

Nominations

2024 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: translation of Þegar Ída litla vildi gera skammarstrik (When Ide Wanted to be Bad) by Astrid Lindgren

2021 - The Icelandic Translation Prize: Hamlet by William Shakespeare

2019 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Ljóðpundari (Poetry Pounder), together with Sigrún Eldjárn

2014 - The Icelandic Literature Price : Fuglaþrugl og naflakrafl (Babbling Birds and Navel Nuances), together with Sigrún Eldjárn

2010 – The Icelandic Translation Prize: Lér konungur (King Lear) by William Shakespeare

2001 – International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award: Blue Tower

1999 – The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize: Brotahöfuð (Blue Tower)

1998 – Aristeion; The European Literature Award: Blue Tower (Shortlisted with 5 other books)

1997 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Brotahöfuð (Blue Tower)

Hlutaveikin

Read moreJólin nálgast. Freysteinn Guðgeirsson verður æ spenntari með hverjum degi sem líður. Á endanum koma þau samt og hann getur loksins, LOKSINS opnað alla jólapakkana. En þá kemur dálítið í ljós sem reynist erfitt viðureignar þó allt fari vel að lokum.

Þættir af séra Þórarinum og fleirum (Tales of Reverends Þórarinn and Others)

Read more

Fuglaþrugl og naflakrafl

Read more

Tautar og raular

Read more

Ljóð í leiðinni: skáld um Reykjavík (Poetry to Go: Poets on Reykjavík)

Read more

Im Blauturm

Read more

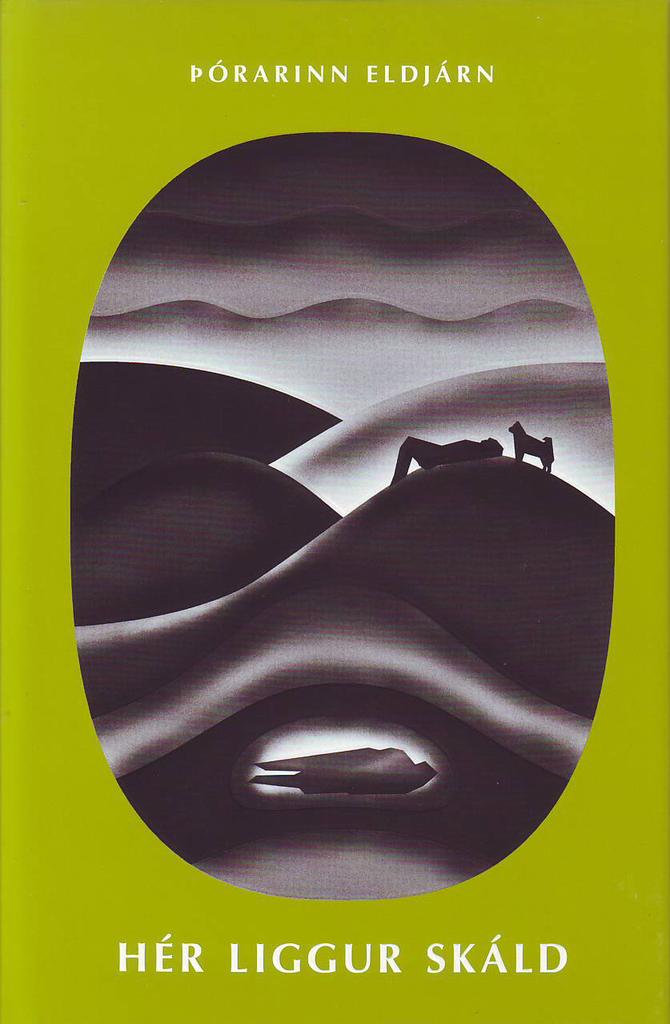

Hér liggur skáld (Here Lies a Poet)

Read more

Vaknaðu, Sölvi (Wake Up, Sölvi)

Read more

Ása og Erla (Ása and Erla)

Read more

Imagine : Að hugsa sér

Read more

Ævintýri Lísu í Undralandi (Alice‘s adventures in Wonderland)

Read more

Örleifur og hvalurinn (Pan Maluskiewicz i wieloryb)

Read moreVeiða vind

Read more

Lér konungur (King Lear)

Read more

The Gruffalo

Read moreJón Gabríel Borkmann

Read more

Greppikló

Read more

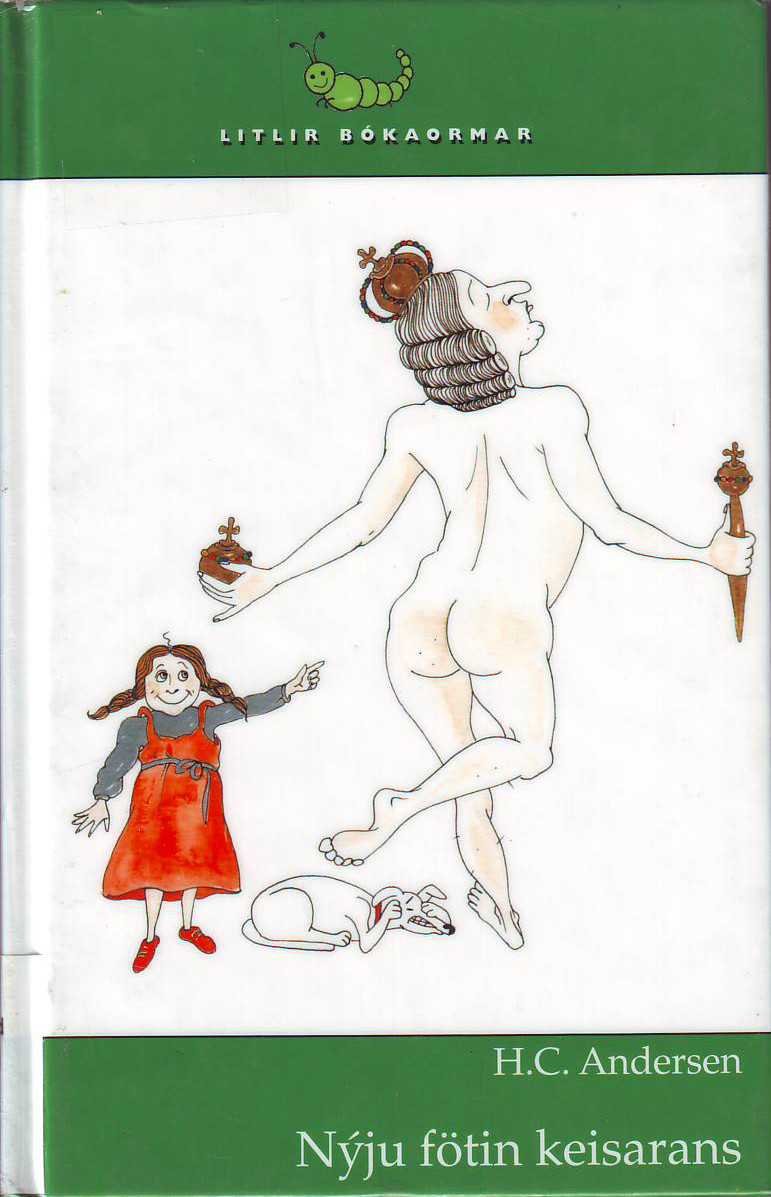

Nýju fötin keisarans (The new clothes of the emperor)

Read more