Bio

Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir was born at the farm Hjalli in Vestdalseyri on July 18, 1930. She studied for the theatre in 1951 and from 1952-1953 she joined a course in acting. Vilborg graduated as a teacher from Iceland’s Teacher Training Collage in 1952 and studied for Library and Information Science at the University of Iceland in 1982.

Vilborg worked as a writer and schoolteacher for years. She published a number of books for children, both fiction and non fiction books. She also published collections of poetry for adults and was one of Iceland’s best known poets. Vilborg translated many books for children and adults, and dedicated herself to promoting children’s issues.

Vilborg was one of the founders of Rauðsokkahreyfingin (Red-Stocking-Feminists) and had a seat at the centre of the movement in 1970. She was a member of the board for the Icelandic Department of Women’s International Society for Culture and Peace. She was member of the board for the Trade Union of Icelandic Teachers of Children, The Icelandic Writers Associsation and The Writers Union of Iceland. Vilborg was a member of the board for the filmclubs Kvikmyndaklúbburinn and Litla Bíó from 1968-1970.

In 1960 Vilborg published her first book of poetry and at that time she was one of a few women in Iceland to write modernist poetry. Her poems appeared in the literary magazine Birtingur, and she published numerous poems and articles in magazines and collections in Iceland and abroad.

Vilborg died September 16th 2021.

About the Author

The cross of housework thrown off and the kitchen knife whetted

In the beginning of the twenty-first century the generation of 1968 has become a bit of a cliché, subjected to criticism and parody in fiction by young authors. The worldview and idealism of this period have become a source of embarrassment and the characteristic fiery spirit rather unsuitable. Some of this criticism is probably justified but still it must not be forgotten that this generation cleared the way for much of what is considered customary today, such as a criticism on the capitalism consumer society, opposition against the warmongery of governments, an altered attitude towards bourgeoisie values and standards, a new view of art and culture, and last but not least, a reshuffling of traditional gender roles.

The feminists of the sixties and seventies have often been criticised heavily from within the nineties feminism, sometimes referred to as postfeminism. This criticism is aimed against dogmatic views and young feminists today are eager to show how the feminist struggle has changed for the better, allowing for a more variety of viewpoints and claiming that the cold-war atmosphere is in the past. Yes, now there is talk about feminisms in the plural, essentialism is a taboo and some would even claim that we women are actually home free and secure, the struggle is over and that it was successful. A conference held on the women’s day, June 19 2002 revealed, however, that all reports of prevalent gender-egalitarianism where somewhat exaggerated. In her opening address, mayor Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir declared her pleasure in seeing so many women at the conference and took this as a sign that the feminist struggle was strengthening again after years of decline, and stressed the importance of a continued fight for the equal rights of women. And she reminded the audience of what had been achieved through the struggle of the sixties and the seventies.

I am one of the young feminists who has fought for a new approach to feminism and a new approach within feminism towards the idea of sex and gender, gender differentiation and the struggle for equality. For this reason the poetry of Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir from the period of sixties and seventies feminism gives me a lot to think about, poetry that engages with women’s status and are just as relevant now as they were then. Vilborg was active in the women’s struggle in the seventies and was one of the pioneers of the famous red-socks movement. These views appear clearly in her poetry which is often ironic and witty but never without a more serious undertone. Vilborg publishes her first book of poetry, Laufið á trjánum (Leaves on Trees), in 1960, at the time one of few women modernist poets. The poems are mostly love poems but a more political tone is struck in the poems “Hver getur ort?” (“Who can Compose?”) and “Ráðið” (“The Board”). In “Hver getur ort?” a question is asked: “Hvers vegna yrkir þú ekki um gleðina?/Reynirinn hefur brumað./Þrestirnir eru farnir að syngja./Vorið kom í gær.” (“Why do you not compose a poem about joy?/The rowan has budded./The thrushes have started singing./Spring arrived yesterday.”) And the poetess answers: “hver getur ort um gleðina/meðan erlendir hermenn hlæja fyrir utan/og ungar mæður kveða á framandi tungu við börn sín?/Hver getur ort um gleðina/- og land hans selt fyrir peninga?” (“who can compose a poem about joy/while foreign soldiers laugh outside/and young mothers sing their children song in a foreign language?/Who can compose a poem about joy/- and his country is sold for money?”). The poem “Ráðið” describes players who sit around a table and “kasta teningum um líf mitt/líf okkar.” (“throw dice for my life/our life.”) But instead of drawing dramatic conclusions from this Vilborg mirrors this image of power play in a feminine viewpoint, wondering “líka þeir voru börn/eins og hann sem liggur í vöggunni/og fyllir herbergið andardrætti sínum.” (“also they were children/just like him who lies in the cradle/and fills the room with his breath.”) Thus there is a conflict between two completely different images, the dread of the one who experiences himself as a plaything and the mother’s warmth and concern towards her child. The child can then be seen as the image of defencelessness, which is mirrored in the powers that be, and over all this reigns the mother. This strong female presence permeates all Vilborg’s poetry together with the leitmotiv of childhood and children. In Dvergliljum (Dwarf lilies) from 1968 the political tone is stronger and the connection with women’s life and struggle is clearer as well. At the same time Christian motifs are striking like in the poem “Páskaliljur”, (“Eastern lilies”) where the women who come to cry at the grave find “gul blóm/sem höfðu sprungið út um nóttina./Vorið var komið/þrátt fyrir allt.” (“yellow flowers/who had bloomed in the night./Spring had arrived despite all.”) The poetess approach to Christianity is amusingly double-edged, for while there are the occasional flashes of strong religion, she is also critical of the lord and his behaviour.[1] A wonderful example of this is the poem “Köllun” (“Calling”) from the collection Ljóð (Poems) from 1981:

Þarna fer hann átvaglið og vínsvelgurinn

hversu oft hefur mig ekki langað til

að varpa af mér húskrossinum

og fylgja honum(There he goes the glutton and the drinker

how often I have wanted to

throw off the cross of housework

and follow him)

The narrator of the poem wants to sit by his feet in “forsælu undir fíkjutré” (“a shade under a fig tree”), wondering over his words and run with him on the beach where he roughly draws “myndir af fiskum” (“pictures of fishes”) in the sand. Then they would go to a taxman’s party or to a country wedding and the narrator would really love:

að gera uppsteit á torginu

hneiksla hina rétttrúuðu í samkunduhúsinu

og velta um borðum mangaranna

í musterisgarðinum.(to create disruption in the square

scandalize the rightful in the synagogue

and upset the tables of the money-changers and dealers

in the temple-garden)

This fantastic vision of Jesus life has a counterpart in the renewal of history that appears in many of the poems about famous women characters, besides striking a clear feminist tone in the image of the cross of housework (literally house-cross). A similarly comical approach to the lord appears in the poem “Kyndilmessa” from the eponymous book (1971), where the lord suddenly starts ay-ing over the housewife where she sits and smokes and she is so startled that she stubs it out. After the lord has ay-ed for awhile about the bad way of the people she gives up and turns on the radio “og poppmessan yfirgnæfði kallinn.” (“and the pop mass drowns out his words.”) The double-edged view of religion appears also in “Og enn sem fyrr” (“And still as before”) from Dvergliljur, a poem about the war in the middle East:

Nú blása þeir í hrútshornin,

sigurvegararnir,

hlæjandi við Grátmúrinn.Með fótinn á hálsi Egifta.

Jórdani og Sýrlendinga

hafa þeir lagt að fótum sér.

Verði setja þeir á vöðin.Og enn sem fyrr

mun ung dóttir hlaupa

út um dyrnar á húsi föður síns

með bumbuslætti og dansi

og fagna bardagahetjunni.Dætur Ísraels,

farið ofan í fjöllin

og grátið.Stuttur frestur er ykkur gefinn.

Altari er reist fyrir brennifórnina.

Grimmur er Jave.

Grimmur er drottinn hins slóttuga Moshe Dayan.(Now they blow into their ram horns,

the victors,

laughing at the Wall of Tears.With their feet on the Egyptians’ throat.

The Jordanians and Syrians

they have laying at their feet.

Placing guards at the fords.And still as before

a young daughter will run

out of the doors of her fathers house

playing tambourines and dancing

to welcome the hero of the battle.Daughters of Israel,

go down into the mountains

and cry.You have been given a short stay.

An altar has been raised for the burnt offering.

Cruel is Jahve.

Cruel is the lord of the sly Moshe Dayan.

The irony is far away and the tone of the poem is flatly serious. As before Vilborg weaves feminine motifs into her political criticism and creates a strong interplay in time, where the ancient world of the Bible and modernity meet in language. This collapsing of time continues into the twenty-first century, where wars are still being fought in this part of the world. In the poem “Karl og kona” (“Man and woman”) Vilborg is still in working with the Bible and still she is having fun at the lords expense. She describes how god himself negotiated with the rebel and the outlaw Moses, until an agreement was struck. “Og aldir liðu.” (“And the centuries past.”) “Þá var það/að Drottni guði lífsins/kom konan í hug.” (“Then it happened/that the Lord of life/thought of the woman.”) And he sends his errant boy Gabriel to give the bashful virgin Maria a secret message and the girl speaks without a second thought “”Sjá ég er ambátt Drottins.”” (“”See I am the lords servant.””) This method, of drawing up images of historical events and casting a new light on them, suits the poetess particularly well and many of her more rememberable poems are spoken from the lips of great women of the past. The best known of these is probably “Skassið á háskastund” “The shrew at the moment of crises” in Kyndilmessa, which refers to a famous scene in The Saga of Njáll, where the hero’s (Gunnar) wife (Hallgerður) refuses him help, when their home is under attack, due to his having hit her earlier. But now “löðrungar og köpuryrði” (“slaps and hurtful words”) are forgotten:

hérna er fléttan

snúðu þér bogastrengég skal brýna búrhnífinn

og berjast líkabæinn minn skulu þeir

aldrei brenna

bölvaðir.(here is my plait

twist it into a bowstringI will whet the kitchen knife

and fight as wellmy house they will

never burn

the bastards.)

Apart from the highly feminine image of the kitchen knife as a battle-weapon in the heroic world of the Sagas, the sentence about “my house”, is striking, a striking comment on the status of Hallgerður within the story: the farm there is only ever seen as Gunnar’s, the woman is not entitled to any property. In her fourth book of poetry, Klukkan í turninum (The Clock in the Tower) (1992), Vilborg again returns to Hallgerður in the poem “Þjófsaugun” (“Thiefs eyes”), where it is described how Hallgerður’s first suitor brings her long-pants, much to the entertainment of the other children (Hallgerður was barely more than a child at the time), and ogles her slimily as he sits and talks with her father: “Nú kallaði faðir hennar” (“And now her father calls her”). Fedra, Hedda Gabler, Anna Akhmatova and the fairy tale princess Snow White all appear in Vilborg’s poetry, og Nora and Anna Karenina meet briefly in “Erbium time” (“Difficult Times”) from Kyndilmessa. There the poetess again draws together different periods and illustrates how little has changed for women, and yet again the reader has to compare the poem to her own time: surely Nora and Anna would have more possibilities today, but women who leave their children are still harshly criticised and still the employment is harder upon women than men, “samkvæmt heilagri venju” (“according to a holy tradition”).

The strongest image of women is, however, the unnamed working woman who is viewing her reflection in the poem “Spegilmynd” (“Reflection”) in Klukkan í turninum.

Mér ætti víst að vera það ljóst

hvað ég er ljót

kona úti í bæ setti saman texta um mig

ekki kann ég að orða hlutina

aftur á móti hitti hún naglann á höfuðið

og nú hlæja allir að mér

víst er ég feit og ljót

strita daglangt við færibandið

með æðarhnúta á fótunum

hendurnar rauðbólgnar

maginn slapandi

samt get ég ekki gert að því

að í hvert sinn sem ég lít í spegil

finn ég gleðina streyma um mig

og ég brosi fagnandi

við spegilmynd minni

ég er orðin alveg eins og

mamma sáluga!(I guess I should realise

how ugly I am

some woman has composed a description of me

I do not know how to put things in words

she, however, was right on target

and now everyone laughs at me

sure I am fat and ugly

toiling all day long at the conveyer belt

with swollen veins on my legs

swollen red hands

a flabby stomach

still I can not help

whenever I look into the mirror

feeling a glow of joy

and I smile in welcome

at my reflection

I have become just like

my late mother!)

Here we witness a description of a woman’s body that is far off any contemporary standards of beauty, a woman who is worn out, swollen and fat – just like the generation of women before her. The poem moves between humour, loss and joy, mixed with a strong criticism on beauty-ideals and the position of the working woman.

In 1981 Vilborg’s first three books were published in one, Ljóð, alongside translations of poetry and poems which had appeared in newspapers and magazines in the years between 1971-1981. Some of these are quite amusing, written in a feminist spirit, like “Myndir frá pressuballi 1972” (“Pictures from the press-party 1972”), where the poetess points out that the wives are only mentioned as such, their jobs are never mentioned – this of course is still the habit of today, as can be read in announcements listing gests in official receptions. The poem “Óður til mánans” (“Ode to the moon”) describing how the woman intends to, after she has finished housework (doing the dishes, taking out the garbage, scrubbing the kitchen floor, polishing the floor of the corridors, vacuuming, dusting, washing), go out to the balcony and “steyta skrúbbinn/framan í mánann/þangað hefur engin kona/verið send með/KARKLÚTINN/ekki enn.” (“shaking the mop/at the face of the moon/where no woman/has been sent with/THE DISHCLOTH/not yet.”) It is interesting to read this poem alongside Ingibjörg Haraldsdóttir’s poems from 1983 about the woman who is about to explode by the kitchen sink and the woman who cleans the living room and airs out the cigar smoke after a hot political discussion of among the men who plan to save the world.

The most striking of these feminist poems is the prose “Draumur” (“Dream”) where the poetess meets with Óðinn, the god of poetry, on a walkabout. She calls to him and thinks she has a few things to say to him, but finds only lust in his gaze. And then she realises “að jafnvel Óðinn sjálfur á ekki nema eitt erindi við konur. Og ég sem hélt ég væri skáld – mér tókst að hrista af mér svefninn og komst yfir í vöku – í sál minni brann reiðin.” (“that even Óðinn himself has only one thing to say to women. And here I thought I was a poet – I managed to shake off sleep and enter wakefulness – anger burning in my soul.”) Icelandic literary history contains famous incidents of poets writing to Óðinn - “Sonatorrek” (“Lament for my sons”) by Egill Skallagrímsson is actually about how the poet came to terms with losing his sons, gaining the art of poetry instead (Óðinn is also the god of death) – but the poetesses stand outside this, the god of poetry has other uses for them.[2]

Even though the poetess was not interested in Óðin’s advances she is not at all averse to love. Many of her poems are love poems and often with beautiful erotic undertones, as in the third part of “Skammdegisljóð” (“Autumn-poem”) in Kyndilmessu. It has snowed during the night “og nú blasir við allra augum/í nýfallinni mjöll/sporaslóð/frá mínum dyrum/að húsi þínu.” (“and now everyone can see/in the new snow/a trail/from my doors/to your house.”) As already pointed out, most of the poems in Laufið í trjánum are love-poems, the first describing a delicate love like “Þrá” (“Desire”), where the memory of love is like a fragrance in the evening breeze: “Þegar hann snertir vit mín/verð ég feimin að anda.” (“When he touches my face/I become to shy to breath.”) Later there are poems describing a broken heart like “Glæpur” (“Crime”), where the blood that used to sing runs from a stricken heart. Vilborg also writes poems about nature, mainly the seasons, and still she manages to find a new form for this classical imagery as seen in the poem “Nú haustar að” (“Now autumn sets out”), where small children with their school-bags bring the autumn.

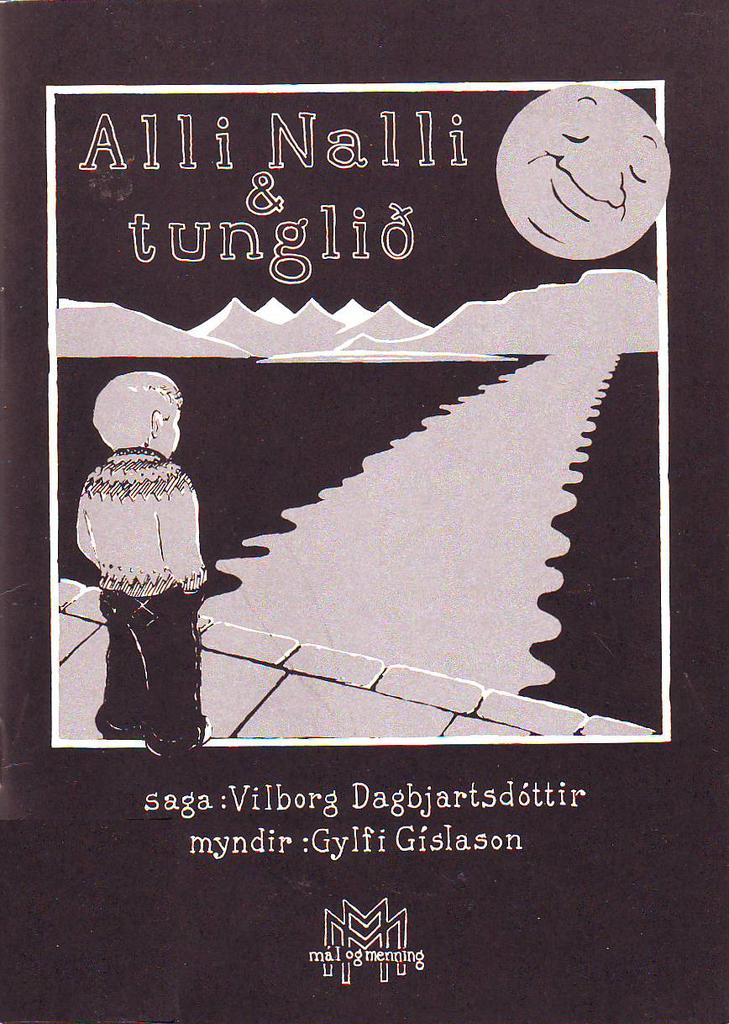

These fresh kind of images of children and childhood are a rich theme in Vilborg’s poetry. She has been a children’s teacher since 1952, and is well known for her children’s stories and work for children and children’s affairs.[3] She has translated a number of children’s books and written numerous textbooks and primers for children. Vilborg’s first publications where the children’s books Alli Nalli og tunglið (Alli Nalli and the Moon), illustrated by Sigríður Björnsdóttir (1959) and Sögur af Alla Nalla (Stories of Alli Nalli) with pictures by Friðrika Geirsdóttir (1965). Alli Nalli og tunglið was later reissued, first in 1976 with pictures by Gylfi Gíslason and then again later with a new moon story in Tvær sögur um tunglið (Two Stories About the Moon) 1981, also illustrated by Gylfi. Sagan af Alla Nalla og tunglinu is one of these wonderful allegories for children. The story explains why the moon is so large and fat. Alli Nalli is not thrilled about his porridge and so his mother puts the pot of porridge on the windowsill so the slim moon can eat it. Every night the moon eats the porridge until it has become round from stuffing itself and then Alli Nalli gives up and demands his share in the porridge. And then the moon grows slim again. Sagan af Labba pabbakút (The Story of Labbi Daddy’s Boy) appeared in 1971 and describes, like Sögur af Alla Nalla, a few events from the life of Labbi pabbakútur who lives in a large house in the city centre. “Það er enginn garður við húsið, en allt í kringum það eru bílastæði” (“There is no garden by the house and all around it is a parking lot”) and “þess vegna er húsið, þar sem Labbi á heima, eins og eyja í bílahafi.” (“this is why the house, where Labbi lives, is like an island in an ocean of cars.”) The book is splendidly illustrated by Vilborg herself and is one of the gems of my own childhood. Other children’s books include Langsum og þversum (Along and Across) (1979 og 1982), Sögustein (A Story Stone) (1983), a collection of stories, puzzles, games and all kinds of entertainments for children, translated and retold by Vilborg together with original material from herself. Bogga á Hjalla (Bogga at Hjalli) (1984) is a story from the country about a little girl who is interested in fairies and elves and Barnanna hátíð blíð (The Children’s Kind Festival) (1993) is like Sögusteinn a collection of various material, stories, songs and information concerning Christmas.

The delightful feeling for childhood and the child appearing in all the children’s books of Vilborg is also present in many of her poems. In “Maríuljóði” (“Mary’s Poem”) in Laufið í trjánum a childlike voice describes her admiration for Maria, who spreads “ullina sína hvítu/á himininn stóra.” (“her white wool/over the big sky.”) The bird wagtail (Icel. maríuerla) is named after her and “í kirkjunni er mynd af Maríu/með gull utanum hárið./Mamma segir að það sé vegna þess/að María á dreng svo undur góðan.” (“in the church there is a picture of Mary/with a gold around her hair./Mother says this is because/Mary has such a wonderful boy.” In these childlike visions the twofold irony of Christianity disappears overtaken by the clear children’s faith. Still the poetess sense of humour appears clearly in the children’s poetry, while they are also characterized by joy and brightness. The poem “Sumardagur” in Dvergliljur is for example drawn in bright colours: “Sólin: stór rauður sleikibrjóstsykur/Skýin: þeyttur rjómi/Aldan: hlæjandi smástelpa” (“The Sun: big red lollipop/The Clouds: whipped cream/The Wave: a laughing little girl”) and the wave teases you who are on the beach baking sand cakes and “steinarnir brosa líka” (“the stones also smile”). The fun is no less in “Barnagælu” (“Nursery rhyme”) from the poetry collection Ljóð, showing us the olden form of the ‘þula’ (rhyme/mantra) in a new form. There are many pranks, but the most amusing is the idea about gender, when it is assumed that mummy once was a little boy, just like him:

segðu mér sögu

segðu mér söguna af því

þegar þú dast í sjóinn

þegar þú braust rúðuna

þegar þú tjargaðir hanann

þegar þú kastaðir grjóti í gumma

þegar þú söngst klámvísuna fyrir ömmu þína

þegar þau laugst að afa þínum

þegar þú skiptir um haus á fiskiflugunum

þegar þú stiklaðir yfir ána rétt ofan við fossinn

þegar þú skreiðst undir girðinguna á rósuhústúninu

þegar þú drapst rottuna

þegar þú gekkst aftur á bak í poll í sparikjólnum

þegar þú reifst nýju svuntuna

þegar þú drakkst brunnklukkuvatn

þegar þú skemmtir skrattanum á sunnudegi

þegar þú kvaldir ljósið á jólunum

þegar þú hlóst í kirkjunni

þegar þú klifraðir upp á dvergasteininn

þegar þú bentir á skip

þegar þú steigst á strik

þegar þú blótaðir þrisvar í röð

þegar þú varst lítill strákur

eins og ég mamma mín(tell me a story

tell me the story of

when you fell into the sea

when you broke the window

when you put tar on the cock

when you threw rocks at gummi

when you sang the pornographic verse for your grandmother

when you lied to your grandfather

when you exchanged the heads of the bluebottles

when you crossed the river just above the waterfall

when you crawled over the fence on the rosehousefield

when you killed the rat

when you walked backwards into a puddle in your best dress

when you tore the new apron

when you drank the bugwater from the well

when you amused the devil on a sunday

when you tortured the light on christmas

when you laughed in the church

when you climbed on top of the dwarf stone

when you pointed at a ship

when you stepped on a crack

when you cursed three times in a row

when you were a little boy

just like I am, mummy dearest

úlfhildur dagsdóttir

[1] This double edged approach is also evident from Vilborg’s biography, Mynd af konu (A Picture of a Woman), written by Kristín Marja Baldursdóttir. Vilborg says: “I have always identified with nature. Had a strong feeling for the lord. But I have not searched for him, rather rejected him. However, he has never rejected me.” Mynd af konu: Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir, Reykjavík, Salka 2000, p. 16.

[2] In an article in a book published in honour of Vilborg, Þræðir spunnir Vilborgu Dagbjartsdóttur (Threads Spun for Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir) Svava Jakobsdóttir points out correctly that Vilborg clearly did not need the old man, she had her own gods of poetry! See “Edda aldinfalda” in Þræðir spunnir Vilborgu Dagbjartsdóttur, Reykjavík, Háskólaútgáfan 2001.

[3] See more about the theme of childhood in Vilborg’s poetry, “Sorg mín er bláklædd stúlka” by Silja Aðalsteinsdóttir, in Þræðir spunnir Vilborgu Dagbjartsdóttur.

Articles

Criticism

Soffía Auður Birgisdóttir: “I mit sind kogte vreden: Om Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir, Þóra Jónsdóttir og Þuríður Guðmundsdóttir”

På jorden 1960-1990, Nordisk kvinndelitteraturhistorie, bind iv, ritstj. Elisabeth Møller Jensen og fl. København, Rosinante 1997, s. 113-116

See also: Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 504, 544-45, 550

Awards

2005 – DV Cultural Prize, Honorary Award

2004 – Honorary Writer’s Salary

2000 – IBBY Iceland Honorary Award: For her work for children

2000 – The Knight’s Cross of the Icelandic Order of the Falcon

1996 – The Jónas Hallgrímsson Award

1982 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Ljóð (Poems)

1976 – The Reykjavík Children’s Literature Prize: For her translation of Hugo by Maria Gripe

1971 – The National Broadcasting Company’s Writer’s Fund

Nominations

2011 – Fjöruverðlaunin – The Women’s Literature Prize: Síðdegi (Dusk)

2010 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Síðdegi (Dusk)

2009 – Gríman, the Icelandic Theatre Awards: Alli Nalli og tunglið (Play by Pétur Eggertz based on Vilborg’s books. As the children’s play of the year)

1992 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Klukkan í turninum (The Clock in the Tower)

Ljóð í leiðinni: skáld um Reykjavík (Poetry to Go: Poets on Reykjavík)

Read moreHvíta hænan (The White chicken)

Read more

Poems in Neue Lyrik aus Island

Read more

Síðdegi (Dusk)

Read more

Alli Nalli og tunglið

Read more

Emil í Kattholti: allar sögurnar (Emil in Kattholt: All the Stories)

Read more

Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir segir sögur (Vilborg Tells Stories)

Read more

Fugl og fiskur: ljóð og sögur handa börnum

Read moreÞað kallast ögurstund (It´s Called the Eleventh Hour)

Read more