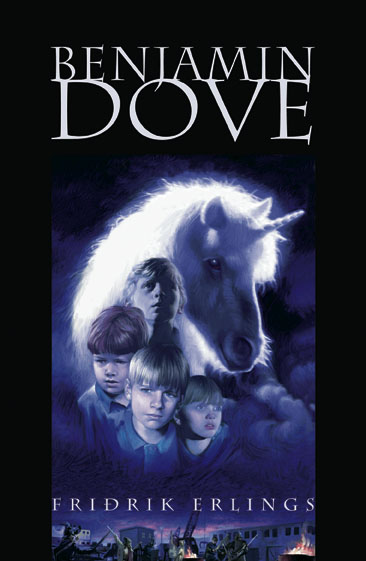

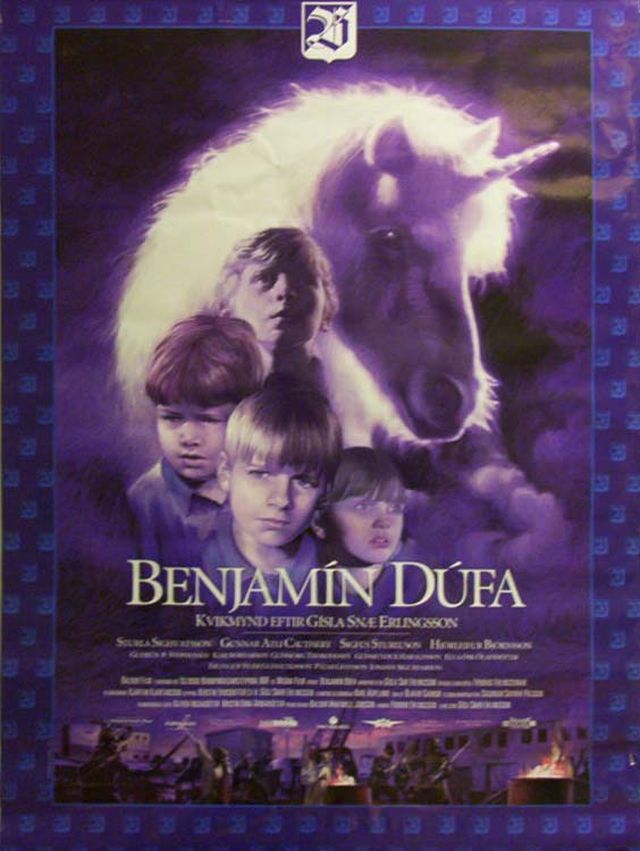

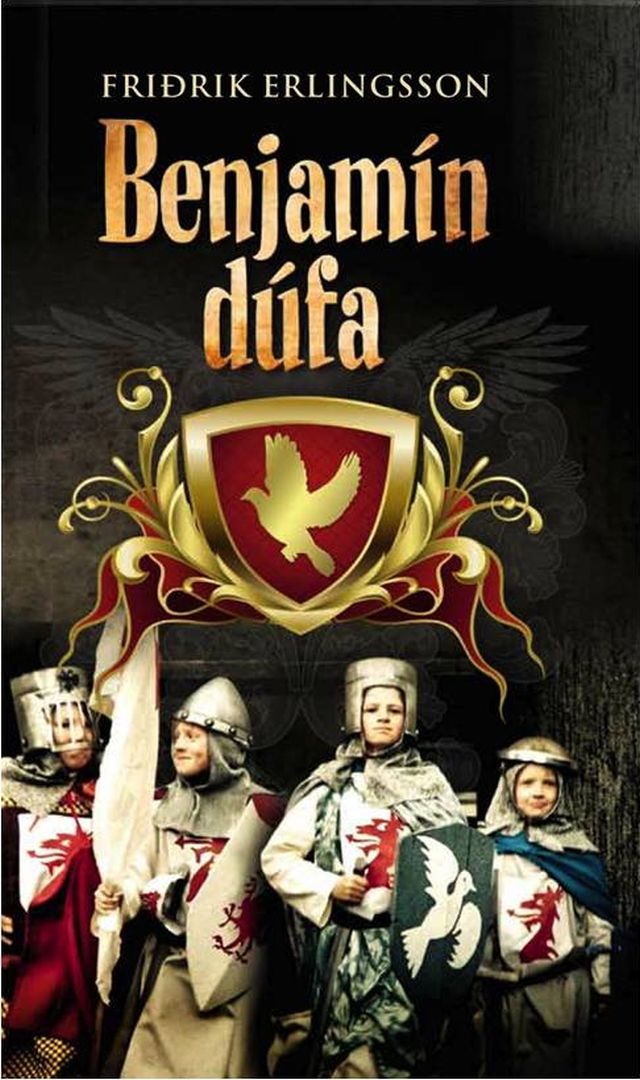

Also published by North-South Books in New York in 2007.

From Benjamin Dove:

1

My part of town was like a little world all of its own. And there all the adventures and mysteries took place that could happen in any world. There were also some rather special adventures and unusual mysteries that only happened there and nowhere else. All the same, my part of town was only a street and a path.

There I, Benjamin, lived in a three-storey block of flats facing the street. My friend Jeff lived on the floor above. Across the street, in a two-storey wooden house, lived Emmanuel, called Manny, with his mother and three-year-old sister.

Jeff and I were twelve and Manny nine. During winter we were together in school and in summertime we played together all day long. And even though the days are twice as long in summer as in winter, it was as though there was never enough time to play. Our mothers had to drag us home in the evenings and force us into bed. It was so unfair; practically bright daylight outside and there was so much we had to do.

Of course we weren’t the only ones playing around in our part of town in the summer holidays. The bullies revelled in it too. In winter they often found it difficult to torment younger kids in the schoolyard and get away with it. But in summer it was as if this lower form of life had broken loose from its fetters. They would dart out of hiding to torment and menace and scare.

In our part of town there were two bullies, Howard the Hood and Eddie the Turd. Obviously no one called Eddie ‘Turd’ to his face, and no one really knew how that handle got stuck to him. On the other hand, Howie’s nickname was obvious. He always wore a black leather jacket and black trousers, and he was swarthy and had black hair as well. Some went so far as to say that even his soul was pitch black.

The bullies were seldom on the prowl by day, so there was no reason to worry about their showing up until after dinner. And it so happened that it was in the evenings that most of the kids met up in one place in our part of town: the Ground.

During the day it was a supervised playground for nursery-school children, but in the evenings and at weekends we had the place to ourselves.

Sometimes there were fights, occasionally someone got hurt, and not infrequently the bullies came to terrorise. And there were never any adults there to intervene if things got out of hand.

Except for Adele.

Her house stood just a stone’s throw from the Ground, behind the block of flats Jeff and I lived in. It was a little wooden house, clad with corrugated iron, painted blue with white window frames, standing in a middle of a pretty little garden with couple of old trees and a white fence.

This was old Adele’s realm. She’d lived there as long as anyone could remember, and all the children called her Grandma Dell. She was the confidante of the housewives in our part of town, protector of animals and children. She never would listen when parents were complaining about our bad behaviour.

‘Children need to play,’ she’d say. ‘Don’t forget that you were once behaving no better yourselves.’

Grandma Dell was the unofficial custodian of the Ground in the evenings and at weekends. And it was not unusual for a child to knock on her door to get a plaster or just a little comfort, a cup of cocoa and a piece of cake. She had a commanding view of the Ground from her kitchen window, and the bullies were never quite at ease going about their murky business, because of her.

Grandma Dell had the biggest cat ever seen in our part of town. It looked more like a lion’s cub, sitting on its throne in the kitchen window, gazing indifferently at the world outside. She called it Socrates. It was hard to imagine that Socrates had ever been a defenceless little kitten, but Grandma Dell had saved him from a dustbin, when someone had tried to get rid of him. Maybe it was because of this experience that Socrates never showed anyone affection, except for Grandma Dell, for no one else was allowed to pat him or scratch him. He showed total disdain for humankind. Even when a big crowd of children were running back and forth on the Ground, he would walk slowly through and not move out of the way for anyone. And out of respect for this gargantuan beast we would stop running and wait while His Majesty proceeded across the playground on his evening walk into the bright summer night.

(pp. 7-11)