Bio

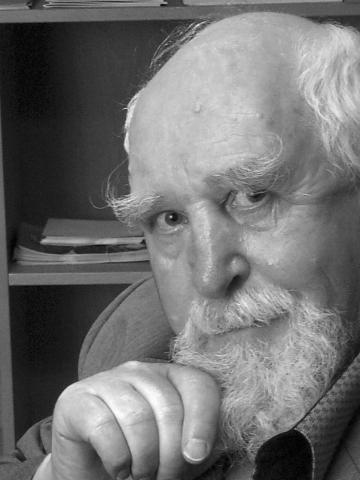

Baldur Óskarsson was born in Hafnarfjörður on March 28, 1932. After finishing his middle school education in Iceland, he was a student at a folk high school in Sweden for one year. He then went to Catalonia, where he studied art history and Spanish literature at Universidad de Barcelona for a year. Baldur was a journalist at the daily Tíminn from 1957 – 1964, and later worked as a news reporter at the National Radio. He was Headmaster of the Reykjavík Art School from 1965 – 1973. He sat on the board of the Icelandic Writer's Union and his literary carreer spanned more than five decades.

His first work, the short story collection Hitabylgja (Heat Wave) was published in 1960. Three years later, he sent forth the novel Dagblað (Newspaper). His first book of poetry, Svefneyjar (Islands of Sleep) appeared in 1966 and since then his preferred avenue was poetry. Baldur published fifteen books of poetry, most recently Langtfrá öðrum grjótum (Faraway From Other Stones) in 2010. The anthology Tímaland (Land of Time), which contains poems in Icelandic and German translation (Tímaland: kvæði = Zeitland: Gedichte), was published in 2000. Baldur was a translator of poetry, mainly of Federico Garcia Lorca. He also wrote on art for magazines and books.

Baldur Óskarsson passed away on April 14th 2013.

Author photo: The Reykjavík Museum of Photography.

From the Author

A Poem Poem

There are poems that wear a tunic and a veil –

they show their eyes.

Others go sunbathing naked.

Those poems are happy – most die in their sleep.

Poems which are born without skin and never get around,

are known to

haunt.

And poems skinned alive –

they struggle against death.

And that is what one calls an ugly separation

From the poetry collection Leikvangur (Playing Field); 1976

Reading

In the hardship of night

I saw tiny fields

light and shadow

like in a wall

of small rocks – like letters.

Read.

The voice was hard

and soft.

I rose to my feet

traced the lines of mountains.

From the poetry collection Gljáin (The Chasm); 1990

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

About the Author

“Greenish lips drink the deep sky” – on the writers of the green pictures in Baldur Óskarsson’s land of time

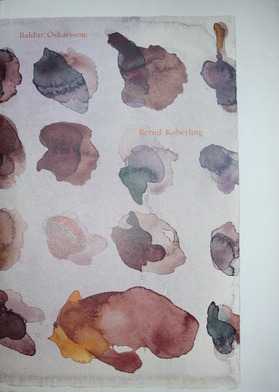

In the poem “Tímaland” ("Land of Time") by Baldur Óskarsson a line goes: “Haustið málar rautt og gult með vatnslitum” (Autumn paints red and yellow with watercolours). The poem is from 1966 and in 2000 the poet published a book with the same name with art by Bernd Koberling. The book is bilingual, in Icelandic and German, and holds a selection of Baldur’s poetry. Koberling’s art consists of watercolour drawings, colourful and rather unruly. The colours run and even though it is apparent that many are studies of nature they are far from being traditional landscapes. These illuminations are well suited to Baldur’s poetry, so full of colours that run in an unruly play of figures, as well as projecting a distinctive view of nature. This appears beautifully in “Vorljóð” ("Spring poem") in Döggskál í höndum (Bowl of Dew in Hands) (1987):

Um samráð við læki og fugla osfrv. –

Skrifari myndanna grænu fálmar sig hingað heim

að vanda fullur

víða kemur hann við

vakinn í dölum sofinn meðal tinda.... Krossfiskur

krossfiskur á austurloftinu þegar ég vaknaði

horfinn inn í eilífðina...

vorljóð, huganir mjólkurhvítar, roðinn að baki.Skrifari myndanna grænu, hingað heim!

[On cooperation with streams and birds etc. –

The writer of the green pictures feels his way home

drunk as usual

he stops by here and there

awakened in valleys asleep among mountaintops... A Starfish

starfish on the eastern loft when I woke up

disappeared into eternity ...

spring poem, milkywhite notions, the red is behind.Writer of the green pictures, come home!]

The writer is probably god, who inspite of cooperation with streams, birds and others, has muddled things up a bit. He has had a drink, probably too many though as he has lost his way and is starting to make small mistakes. And maybe the colours have run a little. The poem also illustrates the sly and warm sense of humour that can be found in Baldur’s modernist and symbolic poetry, often quite opaque and tightly woven – it is not always easy to follow the poets thoughts. “Intricate” was the most common word of contemporary critics, although there was a general agreement as to the quality of Baldur’s poetry, and many claimed him a forerunner in coopting visual arts into poetry.

Baldur’s connection with visual arts appears clearly in his poetry, which is above all colourful and visual. Gestastofa (Guest Room) (1973) is for an example painted red:

the word red, or metaphors for red colours appear in the majority of the poems, and create unexpected associations. In the first poem “Í minningu þína” ("In your memory") a red dice appears, and in “Gestastofa” ("Guest Room") another dice is found, this time accompanied by a rose and sitting in a windowsill. In “Langafasta” ("Lent") we see a spectacular image where a blue trout is bathed in candlelight on a white staple, and “the amber light burns in the green shadow/tunneling/into the burgundy red dome”. The reader finds himself wishing to sketch the colours thus visualising the poem. In “Geisladagur” ("Day of Rays") the evening light colours the “red minds” and in “Interno” rags burned with rust hang on a decaying wooden wall. Dark cracks in the wall are a “remembrance of the wood itself/the pink trunks and red/in the cracked bark” and the poem ends mysteriously in the woods shadowed by some uncertain trepidation. Bloodcoloured lake, red sphere, reddish-blue threads and dark-red wave, a red mass of clouds, a glowing gem – in this way the colour red continues to thread itself between poems, often accompanied by other colours, but always distinctive, even when it is only in the background, as in the poem “Ibis”: “A shining shield on a red fur./Twilight./Ruins and the fossils of time - /the black man-bird.”

Baldur is no less skilled in sketching potent images with words. In the second stansa of the long poem “Kirkjan” ("The Church"), a compelling image of the insides of the body is figured as a metaphor for a house – or is the house a metaphor for the body?

Í fölu myrkri innan fjögurra veggja: æðar og sinar strengdar þvert um salinn, strekktar á rafta, hert við skinin bein sem stingast inn úr svörtu fúnu holdi. Kirtlar til þerris: klasi upp við loft, hringaðir þarmar gerðir upp á snaga, lungu sem hanga rykfallin í horni, nýru sem liggja kramin út við gaflinn í fölu myrkri innan fjögra veggja, í grafhvelfingu meðvitundarinnar.

Og gulur bjarmi drýpur. Hvaða högg ... heyrast – sem stigið þungum frosnum fótum á fjalagólfi niður.

Hvaða högg?

Úrið sem mælir tímann undir kodda. Hjarta mitt kviksett, múrað inn í gaflinn.

Í strekktum æðum stígur marið blóð. Á strengdar sinar leikið hröðum höndum. Og lungun grípa andann snöggt á lofti en nýrun herpast saman út við gaflinn; sjá þarmakippan gefur frá sér slím, og klasinn fellur. Klasinn fellur ofan. –[In the pale dark within the four walls: veins and sinews strung accross the hall, stretched on wooden beams, hardened to the smooth bones that pierce black decayed flesh. Glands hung out to dry: a cluster right up in the ceiling, looped intestines reworked on a hook, lungs hanging dusty in the corner, kidneys crushed by the end wall in the pale dark within the four walls, in the crypt of consciousness.

And yellow light drips. What beating ... is heard – as if heavy frosen feet step onto wooden boards.

What beating?

The watch that measures time under the pillow. My heart buried alive, cemented into the headboard. In the stretched weins steps bruised blood. On the strung sinews played by fast hands. And the lungs gasp suddenly for breath but the kidneys contract at the end wall; see the loop of intestinces ejects mucus, and the cluster falls. The cluster falls down. -]

The poem is in Baldur’s first book of poetry, Svefneyjar (Sleeping Islands) (1966) and it is strikingly graphic. In it we see simultaneously images of horror and myth. The feeling for space is multiple, in the beginning it is spacious, where veins and sinews are stretched accross the hall, but then it shrinks into a crypt of consciousness, and we find ourselves suddenly in a bed, with the head on the pillow and the heart cemented into the headboard and claustrophobia and asphyxation takes over.

At times Baldur refers to known artists and describes their pictures in words. In Leikvangur (Playground) (1976) he finds “Giorgio De Chirico” who directs him to a strange tower: “Hann er blár – segir hann – og rauður/hvítar súlur allt í kring á hæðum,/kemur í ljós nýmána .... hörfar/eins og regnbogi” (It is blue – he says – and red/white pillars all around on hills,/appears in new moonlight .... draws back/like a rainbow). In Hringhenda (Circumstanza) (1982) there is a poem on “Edvard Munch and others”: “Two beings – fiery red and blue,/each embraces the other on a black deep”, and in Döggskál í höndum poems inspired by Kandinsky, Þorvaldur Skúlason og Rene Magritte appear, and in “Insula Dulcamara” the poem refers to the eponymous painting of Paul Klee, addressing him thus:

Kæri Páll,

í dag var ég að skoða eyjuna þína, víðan sjáinnfiðlutónn

fettist upp á halanum

í löngum sveig

liðkar háls, reisir makkakvika að kvöldi hneig

Dulcamara, mér datt í hug – eyja dáin[Dear Paul,

today I was looking at your island, the wide oceana tone from a violin

curles it tail

in a long coil

loosens it neck, lifts its manemagma bowed to night

Dulcamara, I thought – island dead]

This idea of drawing in words is formulated in the poem “Sign” in Rauðhjallar (Red Cabins) (1994), where the poet draws a symbolic image of a horned man, a child on a horse and somebody who comes a long long way from above, is four and fire. But first he draws eyes to see the image:

Efst teikna ég gleraugu með augasteina

- þau sjá allt

næst teikna ég manninn

og hann er með horn

neðst teikna ég skötuna skötuna

og hún kemur í manninn

nú teikna ég hestinn

og barnið er hjá hoonum –

litla barnið broosir hjá hestinum –

og svoog svo teikna ég þann

sem kemur langt langt í loftinu

og hann er fjórir

og líka eldur.[At the top I draw glasses with eyeballs

- they see everything

next I draw the man

he has hornes

at the bottom I draw the skate, skate

and it comes into the man

now I draw the horse

and the child is with iiit –

the little child smiiiles at the horse –

and thenthen I draw the one

who comes far far from above

and he is four

and also fire.]

The tone is childish as apparent from the long i-s, and the reader visualises a child’s drawing, possibly of the old mates, Satan, Jesus and God.

Baldur also refers to other poets, he also translates poetry and included in his books are translations of Lorca, Eliot, Soyinka, Machado and Barbara Köhler, to name a few, as well as translations of the works of Japanese poets such as Lí Ho, Sjúang-sjú, Tú Mú and Lí Sjang-jinn.

Even though Baldur Óskarsson is today best known as a poet, he started out as a prose writer, publishing a short story collection and a novel. The novel Dagblað (Newspaper) (1963) is, as the title indicates, a story about a journalist working for a newspaper. As later in the poetry it is the visual power of the author that lends strength to the story. Baldur brings typewriters and printing machinery to life and creates through that a rather threatening vision, for these machines hafe tendencies to eat people. The description of the narrator’s typewriter is great, and amusingly reminischent of hallusigenic schenes from William Burroughts novels.

Hitabylgja (Heatwave) was published in 1960, containing 12 short stories. The stories tell of events in the present or the past, they are highly symbolic, biblical themes figure regularly and many of the stories have a mythological aura. These biblical themes and reflections on god are also a rich theme in Baldur’s poetry, as already indicated in the poems “Tákn” ("Sign") and “Vorljóð” ("Spring poem"). In the part named “Helgimyndir” ("Icons") in Krossgötur (Crossroads) (1970) we are told about an angel who draws the clouds together and lights a rainbow. He is holding a book and steps “with burning feet onto the earth – onto the ocean”, and “inside the darkness heard the thunder speak”. In Steinaríki (World of Stone) (1979) blood is spread on both posts “In this poem”, which starts with the words “a manless ship and many/fragments of a man.”

Other deities appear in Baldur’s poetry, as “Ibis” for example, and a kind of mother/earth – or moon-goddess figuring in a poem in Leikvangur is apparently generously proportioned: “The ample goddess has past by./The worms lift their heads up from the earth.” Here we also see a feminisation, and the feminisation of naturaldeities is a familiar metaphor. Another frequent theme, at times merging with the mythical, is science, particularly astronomy. “In the month of the sun” in Rauðhjallar the crowns of the trees shine in the reign of light, a spider waits by its glittering web, a cat hunts a mouse, “but I am reading about the black-holes in space -/how people think that black-holes become stars”. In this way science swallows the deities, or not, for as it says in “Hawking – preconditioned” in the same book, the new image of the world of physics could indicate that “the world was god.”

Nature is reflected in the whole wide world and the world in nature. Nature is continually on Baldur’s mind, as it is on most poets’, though Baldur does not do traditional landscape poetry – no more than Koberling does traditional landscapes. The landscape appears rather in close up, as a small image, mirror or a slice, as in the the poem “Autumn” in Gljáin (The Cleft) (1990), where the poet meets a group of geese at the border of a pasture, “they were domestic and stared at me”. For him all these birds are alike, and neither can he see the difference between the grass that grew this spring and the grass that fell last year. In the eponymous poem “The Cleft” a myriad of images is flashed: “Black/not black”, “but seagreen colour behind the veil of black/and colour of blood/by the horizon”, “the house with the dark roof/shines in the stream”, “smoked-blue gains the colour of rose/the bowl of the sky” and “night dark night/here passes the time passes/in the light dream/dark/deep night.”

At times there appear almost all-embracing overviews of nature. In such poetic-landscapes the time has its own law as is apparent from “Land of Time”. A vivid image of country, valley or a farm, that takes on a godly form as often in other poems, with references to menger, angels, incence and the voice of the Unknown who speaks from the hills. Seasons collapse together, “the plairi rests under the frosen snow” and “mountains of clay stand guard, ready to turn against spring”. But still spring arrives and “the flora passes me a warm scent”, the father is cutting the grass and then its autumn again and “The autumn paints red and yellow with its watercolours”, and grandfather comes for a visit with a silver-decorated staff and white in his eyes.

The poem is a prose-poem spanning time and space and can in thus be seen as symbolic for Baldur’s poetry in its entirety, and to underscore the travel in time it may be examined how the poem refers to antoher poem from Rauðhjallar. In the poem “Grey-Blue-Green” a trip to Heiðmörk is described, where “The needles tailors the wind, the blue-grey wind, into singing strings, and the moss softens every tone”. The song is “Grey-Blue-Green”. Similarly to “Land of Time” an image of a vivacious nature is drawn, full of colours and sounds. But now the large symbolic context of seasons and gods has been bypassed for a more quiet image of a walk and the symphony of wind and foilage.

In this way the poem follows time and changes with it and the poets approach to subjects is renewed. A striking collision of modern approach and disciplined poetic language appears in Eyja í ljósvakanum (An Island in the Ether) (1998), and it is clear that the language has grown stronger and more finely tuned in poetry’s land of time during the last three decades. The title “Poem” stands on top of an empty page, and seems thus to be announcing the death of this grand form – particularly when seen in relation to the eloquent description of a “Story” on the opposite page: “It is supposed to end/just when started/and start again as surge/under-current”. However, perhaps the empty paper does not at all describe the death of poetry, but its few words and its quietness, as opposed to the surge and undercurrent of the story. The title of the book could thus refer the position of poetry itself, as a kind of island in the technlogical society of electronic media.

The ocean is a regular theme in Eyja í ljósvakanum, often in the conjunction of ocean and sky, where the winged beings who tune the mind “long wings/grey” as it says in “There”. “A Swimmer” decides to let go and give up: “He was in the ocean/the ocean in him – touches the rockbottom and the blue sky/in the same moment”. And the island itself in ether appears thus to us in “One came close”: “An island in ether/bright green!/East of the country/I sail away” and later, “And there I still see it/my island”. A leafy plant grows on a cliff by the ocean, in the red ocean there are strong currents and curved moments, in the story is a undercurrent and in “A Literary Theme” the poem haves his words drip into a sharkfinsoup of a frosen mire, untill they bubble.

Baldur’s poetry is generally termed modernist, as already indicated, and bear marks of symbolism, but there are also surrealist moments like in the poem “Abyss” from Krossgötur. An image is drawn of an abyss, which is both an image of mouth and eyes: “Greenish lips drink the deep sky” and fill the black throat of blue mead, the eyes get stuck to the uvula and “the evening-red tounge reaches slowly around the sholders”. This still image of the sensual abyss is shattered when “a breath of wind goes through the lake” and “the eyes break”. The poem is yet another example of the rich imagery that characterises Baldur’s poetry and in these compelling depictions is joined a disciplined approach to language and the talent to flash effective images. In the poem the reader sees the dark blue sky reflecting in the black water, also reflecting the eyes of the one who is watching and the breeze rippling the water does both, it spoils the stillness of the picture and possible brings the watcer to tears, and the illusion breaks. Breaking of the eyes also refers to death, and the theme of death is frequent, usually presented in figurative language. In the poem “Loft” in Gestastofa the ray of sun leaves a blue glimpse of light on a scythe and forms the black sign of kross in through the window. The narrator of the poem pretends to be sleeping. The lullaby “Bíbí og blaka” forms a variation on this double death-image of scythe and sign of the kross, and the sleep of the lullaby takes on a ominous aura. Still death is figured in the poem “Coin” from the same book, where more play on traditional figures of death is found. The coin reflects the rounded form of the clock that counts the rounded hours of the day. And the narrator of the poem calls upon the reaper who is the traditional image of death, only now in the guise of a reaper of coins (in Icelandic the reaper is ‘sláttumaður’, and the same word refers to the making of coins): “Whose likeness and inscription is this, reaper?”

These poems are like still lifes of death and beauty, sharply drawn moments, sudden sketches that play on light and shadow. The poem is the form of words that is most akin to visual arts, and the concise form of modern poetry is better suited for flashes and moments, than narratives. One swift image is to be found in “Traveling with a bus – going east” in Gljáin, there the evening comes with its balm and “puts it into the eyes of the passengers/And a small boy says quetly:/Mother – see how beautiful eveything is”. It is in these picturesce poems that Baldur’s poetry is at its best, he traps rounded moments and they do not pass, rather “rest, like colour flecks, side by side”, as it says in the poem “Resting day” from the same book. “Now I wrap around me, a day like this”, says the narrator and the poem ends with this perfect, but vivacious stillness, that the poet creates so well.

© Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, 2003.

The line from the poem "Coin" is taken from the book The Postwar Poetry of Iceland. Translated and with an introduction by Sigurður A. Magnússon. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1982. Other translations are by Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir.

Articles

Criticism

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 486

Dröfn og hörgult (Spotty and Towheaded)

Read more

Langtfrá öðrum grjótum (Faraway From Other Stones)

Read moreÍ vettlingi manns (In a Man´s Mitten)

Read more

Endurskyn (Reflection)

Read morePoems in ICE-FLOE, International Poetry of the Far North

Read more

Ekki láir við stein

Read more

Dagheimili stjarna (A Daycare for Stars)

Read more

Zeitland: Gedichte

Read moreTímaland : kvæði = Zeitland : Gedichte

Read more

Speculations, Listening to a Radio Telescope

Read more