Bio

Elísabet Kristín Jökulsdóttir was born in Reykjavík on April 16, 1958. She grew up in Seltjarnarnes and in Reykjavík and spent a year in Greece as a child. She finished her secondary education in Reykjavík in 1987 and has taken courses in script writing organized by The Icelandic Film Fund and taken part in workshops for playwrights at the Reykjavík City Theatre. Elísabet has done a number of jobs on land and see, she has worked as a shop assistant, a model for the Reykjavík Art School, done construction work, worked in fishing factories, been a deckhand on a fishing boat and a housekeeper on a farm. She has also worked as a journalist, done programs for radio, been an assistant director at the National Theatre, and lectured about micro-story writing at Icelandic secondary schools.

Elísabet's first published book is the poetry collection Dans í lokuðu herbergi from 1989 (Dance in a Closed Room). Since then, she has continued to publish poetry, as well as short stories and novels. Elísabet has written a number of plays that have been staged in Iceland and abroad and performed happenings. Her poems have appeared in collections and journals in Iceland and other countries. Elísabet was awarded The Women’s Literature Award, Fjöruverðlaunin, in 2015 for her book of poetry Ástin ein taugahrúga: enginn dans við Ufsaklett (Love is a Mess of Nerves: No Dancing at Ufsaklettur), and also received a nomination for the DV Cultural Prize and The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize for the same book. She received the 2020 Icelandic Literature Prize for her autobiographical novel Aprílsólarkuldi (Cold April Sun).

From the Author

From Elísabet Kristín Jökulsdóttir

I am writing about the picture of me in order to gain independence.

Then I am conflicted about whether I may just be writing to entertain the reader. Because I once met a woman who had cared for me in the nursery school Tjarnarborg and she told me that I had always been trying to tell the other kids stories. Maybe I was also trying to scare them. I do not know what kind of stories these were, but when the woman came home at night, she told her two kids about the little girl who was always telling the other kids stories.

It felt good hearing this because then I knew for sure that I was not a writer because my mum and dad are writers. This had sent me on a big roller-coaster ride. And it also supported this other thing, that I feel good when I am writing, however things are going; I am happy then.

I am writing about the picture of me in order to gain independence.

What are the benefits of gaining independence, both personally and professionally. What is my world like?

The picture of me can also contain the picture of the nation.

And I am writing to make something out of the heritage I have been given, the language and the literature and my vision of the country and the people, myself. I maintain that I was born with a certain outlook on the world; it is a remarkable discovery.

And I am reacting to it when something springs to mind, a phrase, a word, a person, a story.

It is massive food for though, I could write a whole book about this.

And maybe I am first and foremost assembling --- assembling a world which would otherwise be disintegrated.

And then maybe I am also assembling the world anew so that it can disintegrate.

Elísabet Kristín Jökulsdóttir, 2003.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

About the Author

To Pick the Ocean and Demand a Boat: The Writings of Elísabet Kristín Jökulsdóttir

Dans í lokuðu herbergi (A Dance in a Closed Room) is the first book of poetry by Elísabet Kristín Jökulsdóttir (1958-) and came out in 1989. Before that, poems and a play by her had been published in Tímarit ungskálda [a magazine for young poets - trans] in 1987. In this book of poetry a symbolic poetic voice is established which has since stayed with Elísabet´s writing in its various forms; poems, prose, micro fiction, short stories, plays and novels. An exploration of her works shows a playfulness and a search in different genres and clearly, here is an author who has not remained idle. The themes that Elísabet is constantly addressing can be found as early as in her first works. Writing becomes a way to get to the self, and Elísabet´s writing is both self-searching and self-creating. “I am writing about the picture of me in order to gain independence” says Elísabet about her writing here on the website (see ""From the Author). With these words – to write about the picture of oneself - one could say that she links herself to a long tradition that can be traced all the way back to the beginning of romanticism in the 18th century, when such a self-creation of authors started to emerge. This is a search for one´s origins in words, in another world and in dreams, which may frequently be made of stronger material than the material world itself and what we call reality. This poetic battle of imagination and reality is evident in all of Elísabet´s writings, and the first prose play in three acts from 1987 (pub.1991), Stúlka á bar (A Girl in a Bar), describes it well:

III

I don´t understand all that bullshit about imagination and reality, said the girl to the bartender, who was polishing glasses and wiping off the table in front of her.

And it ends with:

Or is it like this: that the imagined can become real, when one cannot say it with some kinds of words ... said the girl.

(Ljóð ungra skálda (Poems by Young Poets): 31. Editor: Guðrún S. Jakobsdóttir. Fredriksberg, 1991)

Imagination comes before reality. Elísabet´s prose is symbolic, emphasizing the imagination and the inner world that deals with what is outside. The unseen against the seen. Supposedly, the most important things are invisible to the eyes, if one is to believe the words of the Little prince in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry´s eponymous novel, words which Elísabet has referred to. In the eyes of the French symbolists at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, the poem was a secret, a dream that expressed an unseen reality. Elísabet´s poems are more than a dream. The dream is more real than the material world. It contains the psyche itself and within it reside love and grief and an endless flow, corresponding to nature. The sensory merging of body and nature are common. Thoughts and emotions become a waterfall, which crashes down. “And feeling like there must be an abyss beneath these feelings. Or are they thoughts.” – says in a poem from Dans í lokuðu herbergi. A prominent theme is the child in a big, dangerous world. The child is afraid of the boogieman on TV, but the real subject is the fear that lives within. The boogieman is inside the child´s head. The abyss of the world and the person becomes the great expanse that nothing can contain. Elísabet is a poet of emotions, and her latest books of poetry are further proof of this. The title of her next book of poetry, Sjáðu, sjáðu mig. Það er eina leiðin til að elska mig (Look, Look at Me. It Is the Only Way to Love Me) which came out in 1995, says more than many words. In the meantime she published a short story collection and micro-stories, which I will deal with later.

The poems call on the reader; ask for his eyes and perception of these words of emotions – “look, look at me.” Love and sorrow are also central themes. Novalis´ (1772-1801) blue flower of the romantic era becomes blue birds and blue tears, blue water. Melancholy and inner anguish are displayed, mixed with an inextinguishable desire. Depression is a large, black bird, which locks its claws into the poetic I. The woman is powerless against all this sorrow. The poems cry themselves towards the reader in a singular flow. In the third book of poetry and also the second latest when this is written, Vængjahurðin (The Winged Door) from 2003, the desire to escape from sorrow has become a desire for love. It describes a desire that lives in the body, the mind, and the self – but first and foremost in dreams. The bird´s wings from the previous poems are now a butterfly that flutters about the book in the beginning and the end, flutters when love is accepted and the dream thus given life.

The book is divided into 108 short poems or parts of poems which all work together like drop flow in a water tank. The poems become a kind of bloodstream of poetry. They are physical and conscious of their mortality. They are body, nature, crazed desire – everything that lives for the moment, merging and splitting apart. And as her previous poems, they long to share their loneliness, to escape out of fiction and turn the dream into something more than an inner reality. As before, the poetic I is a woman who lives and breaths within her inner live and outside it is “he.” One night he opens up a winged door for her in a dream. As a result, the reader´s mind starts to look for flapping heart valves.

The poems are written in the period between June 8th and September 18th 2003. It is probably the same number of days as the desire for love, expressed in the poems in Vængjahurðin, lasted. Love is life, poem, light, and above all a belief the poetic I succumbs to: “Do you want to have control over me, so that I lose the body, / and feel that something is in control of my body”. This constant search for a union, namely a union of inner and outer life, becomes very tangible in the desire for love. Love and belief in it becomes poetry. But comparing love and faith is not so far-fetched. Church father Augustine (354-430) wrote about the inner desire inherent in faith. He saw love as kind of desire, a request, movement – which stays in a certain channel but has one goal (Arendt, Hannah: Love and Saint Augustine. Editor: Scott, Joanna Vecchiarelli; Stark, Judith Chelius. Chicago/London 1996).

In Vængjahurðin, love is a poem and the poem is love, and with each poem further steps are taken to approach the goal. It says for instance:

This poem is a prayer, to tell you that you are life, because I cannot make sense of you but always want you.

In this context one might agree with Julia Kristeva when she says that love has succeeded religion in the 20th century. This is the crisis of modern man in her opinion because it entails an eternal lack and a lack of love, since the goal can never be reached; it remains forever far ahead in the desire for love. (Kristeva, Julia: Histories d´amour. Paris 1986).

Looking into each other´s eyes to share the loneliness,

not putting it into words. Otherwise it will not be shared.

(Vængjahurðin, p. 44)

In Roland Barthes´s A Lover´s Discourse,he deals, among other things, with the discourse that lives within the subject, who stands alone with it inside its forest of solitude. A common feature of faith and eroticism is that they have their most exalted existence in isolation from any external objects. (Barthes, Roland: A Lover´s Discourse. Fragments. (Fragments d´un discours amoureux, 1977) 2002).

Loneliness, mixed with desire, characterizes these three books of poetry by Elísabet, each in their own way. A search for an object on the border of the outer and the inner world, to make peace between the self and the struggle that the subject goes through in the far-out world of the inner life:

Allow me to be floating.

Allow me to fall.

Allow me,

I cannot live anymore like this.

I know nothing about who I am.I am a crazy woman.

I just want to be able to sing.

Sing until my chest rips,

and everything outside

quivers in song,

which I sense

on these borders.(Sjáðu, sjáðu mig. Það er eina leiðin til að elska mig, p. 24-5)

Rúm eru hættuleg (Beds are Dangerous) from 1991 is Elísabet´s second book, and contains a collection of dangerous short stories. Again, we encounter the child in a questionable world, where a common human fear lives, mixed with the innocence that can also be found in her first poetry book. Who does not remember being afraid of something lurking under the bed? This feeling may even always be with us, the sense that something is lurking in a dark corner, under a bed or inside a head or a heart. There is a fine bridge between honesty and irony here, and this outlook on the world is an important characteristic of the author´s writings that can especially be found in her short- and micro fiction; not so much in the poems. The short stories are the beginning of her latter micro stories that paint a tragicomic picture of the world. There is a sense of sharp nostalgia and production of memories. The family, dad, mum, children and a granddad who tells stories which all begin with “once upon a time.” The Ella Stína micro stories more often than not open with that same fable style. The stylistic characteristics of the micro stories give the narrative voice an absurd space where sarcasm with a serious undertone is used. The reader often does not know whether to laugh or cry. Galdrabók Ellu Stínu (Ella Stína´s Book of Magic) first came out in 1993 and goes hand in hand with Lúðrasveit Ellu Stínu (Ella Stína´s Brass Band), which was published three years later. It could be said that a tragicomic fable and parable style is what most distinguishes Elísabet´s writing, as she brings to life the absurdity of existence. Fótboltasögur (Football Stories) from 2001 is a book that falls into that category, but this time the treatment of the subject matter is different and less homogeneous, the theme being football, and a humorous tackling of metaphors that derive from football. The micro stories display a need to simplify a complex world, in the same way a child would. The child may pick the ocean and demand a boat, like the seemingly mischievous little girl with the blue eyes in The Brass Band. But the ocean is often in close proximity to the emotion writing, and refers to the ocean within people. Adventure and horror are even mixed together. A ghost story turns into an adventure with diamonds and weird fish, as in the poem “Haf dans” (""Ocean Dance)"" from Elísabet´s first book of poetry. The horror of the ghost story is counteracted with an atmosphere of adventure, and the bodies at the bottom of the ocean are laced with diamonds.

A “children´s story” of marvels and fancies, Aðalheiður og borðið blíða (Aðalheiður and the Gentle Table) came out in 1998; a year later a serious and tragic undertone takes over in the novel Laufey. The story of Laufey, who lives in a Reykjavik ghetto, tells of considerable danger, even horror. Themes, which could be associated with desire for love, sorrow and human solitude, are still present, but appear in a different guise in the novel. The world is hostile and is not made for everyone. The dual-voiced narrative tells of Laufey and Þ. The reader follows the thoughts of these two characters in turn and is aware that something terrible will probably happen. The characters are troubled and the minds lead them both astray, in different ways for each of them. The stylistic devices of the story recall the author´s micro- and short stories, where sarcasm and honesty are mixed together, although the story Laufey has more tragic uncanniness than adventure. The narrative is spliced together from brief short story-like fragments from the minds of the characters. It is therefore fitting that the story was adapted into a play, Laufey´s one act play.

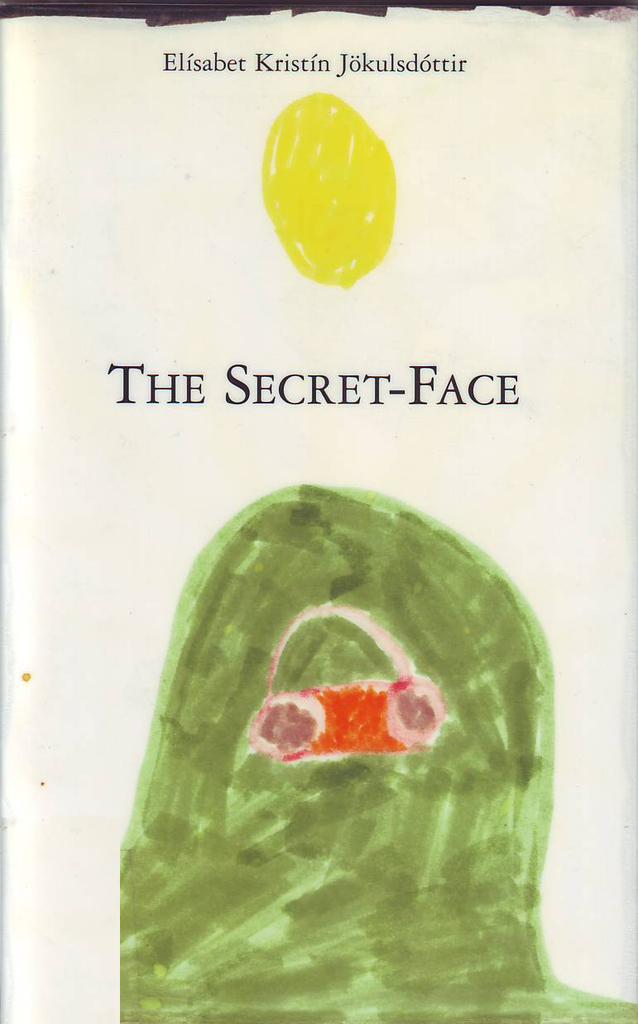

The author has relished the challenge of playwriting. Eldhestur á ís (Firehorse on Ice) from 1990 was her first work for the theatre that was staged. The theatre company called itself Eldhestur and was housed by Leikfélag Reykjavíkur (The Reykjavik Theatre Company). The playwright worked closely with the director and the actors, a process that is becoming increasingly common today. Since then Elísabet has written plays, short plays, one act plays and radio works for various groups. The latest one is The Secret-Face, which was created in collaboration with a theatre group and shown in 2004 at Iðnó theatre in Reykjavík. The work was written and performed in English, and was probably meant to be exported in some form, as well as giving non-Icelanders in Iceland a chance to enjoy it. In The Secret Face a woman fights different voices of the self and tries to bury her obsessions and find out what is real and what is imagined – or vice versa. This work combines love, sorrow and loneliness in the absurdity of life, which probably is made from emotions anyway, resulting in hilarious theatre akin to absurdism.

Elísabet Kristín Jökulsdóttir´s works are personal and all their production refers to the private world of the self. Her poems and plays recall the writings of Nína Björk Árnadóttir (1941-2000). The personification of emotions like sorrow and love are common in the lyricism of these two Icelandic female authors, where dangerous conflict takes place within one´s inner world. With her style of micro fiction, Elísabet then enters the realm of honest absurdity that is on the border between laughter and crying. One can describe her as a writer of emotions who says: “this is me.” The following micro story is a good example of this:

A Girl with Feelings

Once there was a girl who always had feelings. She was literally bursting with feelings, sent them out in all directions and used them mostly to get crushes on boys and so she blazed with love and lust. The girl was burning like a bonfire on New Year´s Eve and lacked control, humility and confidence to channel these emotions. Her spirit was being eroded out of her head and heart and in this condition she trod along the winding path towards the hidden mountains. Providence sent her then two angels with a message; the angels assisted the girl and showed her the truth. When she emerged from the ocean the earth was on fire and she understood that God had created the world out of emotions, and that emotions are fuel for ideas. She dreamt about creating the world in the theatre and calling the play Children Own a World because children were always telling her why the sky was blue, what was a stream and a dream, something about electricity and fruit and asking her to remember the magic.(Galdrabók Ellu Stínu, p. 62)

“Stelpa með tilfinningar”, the final story in Galdrabók Ellu Stínu, shows well the author´s personal point of view and sums up her basic raw material: girl, flowing emotions, head, heart, fear, search for security and truth, world of theatre, children and magic – creating one´s own world. I am writing about the picture of me, says Elísabet, which recalls the Finnish author Edith Södergran (1892-1923), who said she was creating herself through her wri ing, that her poems were the way to herself. The writings of this Icelandic author are intertwined with the self. Armed with her emotions, the authorial voice weaves her way forward in a private world.

© Soffía Bjarnadóttir, 2005.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Awards

2020 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Aprílsólarkuldi (Cold April Sun)

2018 - The Icelandic National Broadcasting Servie Writers' Fund

2015 - The Icelandic Women's Literature Prize, Fjöruverðlaunin: Ástin ein taugahrúga: Enginn dans við Ufsaklett (Love is a Mess of Nerves: No Dancing at Ufsaklettur)

Nominations

2021 - The Icelandic Women's Literature Prize, Fjöruverðlaunin: Aprílsólarkuldi (Cold April Sun)

2016 - The Nordic Council’s Literature Award: Ástin ein taugahrúga: Enginn dans við Ufsaklett (Love is a Mess of Nerves: No Dancing at Ufsaklettur)

2014 - The DV Cultural Award for Literature: Ástin ein taugahrúga: Enginn dans við Ufsaklett (Love is a Mess of Nerves: No Dancing at Ufsaklettur)

Saknaðarilmur (The Fragrance of Loss)

Read moreÞegar fullorðin dóttir missir móður sína skríða áföllin upp úr gröfum sínum og veröldin fyllist af saknaðarilmi.

Næturvörðurinn (The Night Watchman)

Read more

Anna á Eyrarbakka (Anna of Eyrarbakki)

Read more

Ástin ein taugahrúga: enginn dans við Ufsaklett (Love is a Mess of Nerves: No Dancing at Ufsaklettur)

Read more

Heilræði lásasmiðsins (The Locksmith´s Advice)

Read more

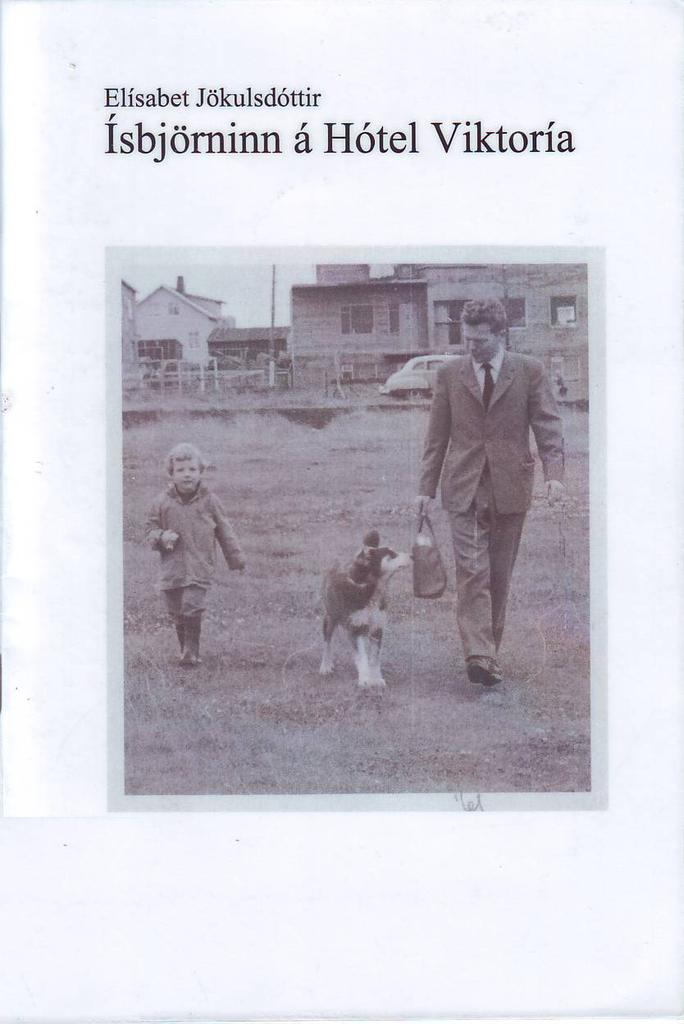

Ísbjörninn á Hótel Viktoría (The Polar Bear at Hotel Viktoria)

Read more

Síðan þessi kona varð trúuð hefur hún verið til vandræða í húsinu (Since this woman became religious, she has caused trouble in the house)

Read more

Englafriður (Angelpeace)

Read more

The Secret-Face (Blinda kindin)

Read more