Bio

Guðmundur Andri Thorsson was born in Reykjavík on December 31st 1957. He graduated from M.S. high school in 1978 and with a B.A. degree in Icelandic and comparative literature from The University of Iceland in 1983. He did his Cand. mag studies at the same school from 1983 - 1985.

Guðmundur Andri worked as a journalist and literary critic at DV newspaper and Þjóðviljinn for some time and for years hosted his own radio program, Andrarímur, at The Icelandic National Radio. He was editor of literary journal Tímarit Máls og menningar from 1986 - 1989 and again from 2008 to 2017. He also worked as an editor for Mál og menning publishing house (later Edda) from 1987 - 2004 and for Forlagið Publishing from 2008 - 2017. In 2017 Guðmundur Andri became a parliamentarian for the party Samfylkingin. On top of this, Guðmundur Andri plays the guitar and sings with his companions in the band Hinir ástsælu Spaðar.

Guðmundur Andri's first novel, Mín káta angist, was published in 1988 and since then he has sent forward other novels and he has also written a biography about his father, the writer Thor Vilhjálmsson. He has overseen a number of books in his career, as well as translating fiction by foreign authors, among them the novels A Short History of Tractors in Ukranian and Two Caravans by Marina Lewycka. Guðmundur Andri has written a large number of articles on culture and social issues in newspapers and magazines, some of them appeared in his book Ég vildi að ég kynni að dansa (I Wish I Could Dance), published in 1998. He received the DV Cultural Prize for Literature for his novel Íslenski draumurinn in 1991. The book was also nominated for The Icelandic Literature Prize in the same year. The novel Íslandsförin var nominated for the same prize in 1996. Guðmundur Andri received an award from the National Broadcasing Company's Writers' Fund in 2013. Some of his work has been published in translations, such as the novels Valeyrarvalsinn and Sæmd.

From the Author

From Guðmundur Andri

My friend Jón Thoroddsen is the son of Drífa Viðar, a painter and a writer, and Skúli Thoroddsen, who was a popular doctor at a time when patients had a near unlimited access to their doctors. Sometimes as a child, Jón would answer the phone when his dad was not home and patients would start listing all their ailments to the child, who was quick with answers and was even able to give some good advice and instructions. Once, when Jón was seven years old, someone asked him what he wanted to do when he grew up. The story goes that the child replied without hesitation, his tone of voice indicating life experience, even certain world-weariness: I think I might as well become a doctor. It is the only thing I know how to do anyway...

Today he works as an art instructor. I myself would at that age not have said that I was going to be a writer, or anything else, since people who called my father did not have anything in particular to discuss with me. Yet I could not avoid gaining a certain insight into the writer’s job. I associate it with the smell of coffee from my father’s room when he was writing, and with the rhythmic and industrious sound of the typewriter when my mother was tapping out his prose. I never planned to follow in my father’s footsteps; it’s just that this is the only thing I know how to do.

But then I do not even know how to do this.

My methods for writing are tentative, I find it difficult to organize the material, I fumble my way through the story, not knowing what awaits me, run headlong into rough terrain, only to have to turn around, I bump into walls, meander down alleys going nowhere, led by an inkling of a smell or a memory of a rustle. Then I am happy. I have felt how a story has its own principles that I am getting to know, its own time that I will adopt, its own life that I will allow its own motion. I have found that characters in a story are made and evolve according to the inner logic of a given novel, although they are not correct by society’s standards – not typical, even absurd.

I look for the skewed characteristics in a person. What intrigues me is something in a given person or a family that does not quite make sense, because I believe it is in this skewness that one’s character resides. I would certainly like to do my bid against the fashion police’s strict rationing of character traits in accordance with the restriction policy of the psyche in late-capitalist consumer society; yet I think what fuels me is deep-rooted eccentricity. I want to find the magnificent in the trivial, the historical in the mundane, the loveable in the dull. Despite an impulse to turn things on their head, I wish to be realistic, to tell the truth: to capture something “as it is”. These tendencies do not always fit nicely together and sometimes when I am writing the chorus of a song by Megas comes to mind: Fata Morgana as stranded I stood/ I can’t find a hat that goes with the hood...

When I write, I sometimes feel like a false clairvoyant or con man. Almost daily I am visited by characters that I do not know where are coming from. Maybe it is revelation, I do not know, yet a great majority of them die while still in my head, they dissolve, I miss them and watch them being sucked back into their black hole. Every now and then I react quickly enough to describe something, but it is only their shadow. These people are accompanied by dialogue that sails into my head at a steady pulse. A voice reigns in my head that is not my voice, but that of an intermediary between the world beyond and the letters streaming from my fingers. I have here worn out lights and moth eaten veils. Then the words appear and line themselves up into voices, music is made...

That sounded vaguely spooky. Maybe this explains why:

As child I spent a part of most summers in Akureyri. I acknowledge that I tend to make too much of how these visits have affected my uneventful life, and am fully aware that I could tell other stories from my upbringing and formative years which would throw an all together different light on me... nonetheless, in Akureyri I stayed by the town square in the house of my grandparents, and would gobble sweet dumplings (kleinur) that granny deep-fried and fed me constantly – and read. There were few children of my age around and efforts to get me to mix with the youth of Akureyri were largely unsuccessful. I felt increasingly at home on the odd bench in the book room where it smelled of old books and granddad’s tobacco. All the Icelandic literature imaginable was there at my fingertips, except modern novels. These were all books that had been chucked aside. What I found there were national heritage studies of various sort, municipal information, and stories and accounts. The folk lore collections of Ólafur Davíðsson and Jón Árnason and ancient histories of Nordic countries, back issues of Spegillinn which I found a hilarious magazine, Ófeigur, the political periodical of Jónas from Hrifla and Sögur Ísafoldar which was a collection of translated popular fiction from before and around the year 1900. In a closet, there were piles of the Danish magazines Hjemmet and Familie Journal and old and yellowed serial stories from the Morning Newspaper (Morgunblaðið) that my grandmother had cut out, and often told of unhappy sex-bombs. Some of these I read and also looked at announcements for dances with the bands Tíglarnir (The Diamonds), Ásar (Aces), Gosar (Jacks) and other players, and followed a rather serious comic series about a Tintin-esque adventurer called Markús. Mixed in with these were books about prescient dreamers, clairvoyants, psychics and dead Icelanders that belonged to granny. All these were dead books that came to life before my eyes – in a certain sense this reading of mine was similar to a haunting. Every single day I was inside some world or another. When I left the house, I would wander about absent-mindedly in the kind of a daze known to everyone who has been a bookish child.

I hardly know why I am recounting all this, except that all this falls under literary experience of things that were by no means written for a boy like me, that were not meant for me and I hardly even related to. I was from Reykjavík, a child of the Beatles, I read Óli and Maggi, Jenna and Hreiðar and Kim, the usual that is – but in the summertime this rugged and barren literature would be waiting for me in Akureyri, in which everything was written with heavy sincerity, not a simile in sight, no metaphors apart from truncated agricultural terms, no ambiguity, no “play with the language”, hardly even a paragraph break – some books may even have had gothic lettering – yet there were magical wonders which came alive in front of ones eyes, a laden atmosphere which engulfed one, a world beyond this world. This is where I learnt how to read. I learnt how to connect with human life through text – distant life, strange life, antiquity.

I write text which is vastly different from that Akureyri literature of my childhood, inspired by different texts, different sounds, different music and different literature. Yet when I sit down and think about myself in this way, I feel that I write in order to recapture a sense which has followed me from these days of an open mind, young solitude and unlimited dumpling eating.

Guðmundur Andri Thorsson, 2007.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir

About the Author

THE FATE OF ICELANDERS – ON THE NOVELS OF GUÐMUNDUR ANDRI THORSSON

A few years ago, a friend of mine woke up to a scream in the night. Outside, a man wearing a white nylon shirt stood in the middle of the street, waving his hands and yelling: “You’ve ruined my life!” so loudly that his voice carried all across the neighbourhood. The man was of course drunk and of course his grievance was with some woman who had of course given up on living with him [...] his next appearance was up on the roof, where he shouted: “I’ll jump! I’ll jump!” The woman saw that this would not do and decided that desperate measures were needed [...] as his wife’s desperate measure got closer, it turned out to be an old lady: apparently the unfortunate soul’s mother, who had presumably received a call from his ex-wife. The old lady called up to him in a tender yet determined tone: My dearest Jóhann, I would ask that you stop and think about this! As if freed from a spell, the madman immediately turned into a confused and meek little boy.

(I Wish I Knew How to Dance, p. 173)

Thus reads Guðmundur Andri Thorsson essay on the societal role of writers. Guðmundur uses this tale as an analogy, explaining that the role of writers is to do as the old lady does, the one “who reminds the crazed man to think”. However, he also speculates that more often than not their actual role is that of the drunken man himself “who suddenly barges into peoples’ lives and rants and raves in public about the ruins of his private life, even though nobody much cares for such insights”. A writer’s ambition, says Guðmundur Andri, is to be able to play both roles, “to be not only the one making the racket and waking up everyone in the neighbourhood, but also the one who tries to open other peoples’ eyes through compassion and candour“ (p. 173-174).

It’s tempting to align Guðmundur Andri the writer with this analogy of the drunken man and his mother. However, I will not speculate here as to whether Guðmundur Andri has more in common with the drunken man or the mother—or if he is in fact a mixture of the two. One thing is for certain: when it comes to his fiction and non-fiction writing, his intent is that of an author who wants to make a clamour and wake people up; who wants to get them to think.

Guðmundur Andri’s first novel, My Joyous Despair, was published in 1988. Since then he has published three novels as well as countless articles in newspapers and magazines, some of which appear in the essay collection I Wish I Knew How to Dance (1998), which is quoted above. Furthermore, Guðmundur Andri has edited, prepared and selected materials for all kinds of literary journals and republications—often providing a foreword or afterword to such collections as well. Among these is a selection of 19th century Icelandic literature, which was published in 1992 under the title The National Poets. He also supplied material for and served as an editor of the fourth and fifth volumes of Icelandic Literary History, which was published in 2006. He has written numerous song lyrics, in particular for his band, Spaðar (Spades). He also had a spell as the chief editor of the literary journal Tímarit Máls og menningar.

Overall, Guðmundur Andri’s work falls into two categories: fiction, which includes his four novels and a few short stories, and non-fiction, which consists of writings about literature, art and cultural or social matters. Here, we will be focusing on his fiction. Still, it is difficult to separate the two as there is a strong connection between Guðmundur Andri’s fiction and his writings about culture. You might say that his fiction has a societal angle while his cultural criticism is tinged with a fiction writer’s flare. Sometimes the two forms actually combine. One might be tempted to consider the drunken man in the extract above to be the same person as the stranger that the protagonist of My Joyous Despair comes across at one point: “On Laugavegur, a man was standing in the middle of street, wearing a tattered white shirt that flapped open over his brown pants. He shook his fist and shouted: You’ve ruined my life! He cried and screamed. He was going to kill himself as well as her” (p. 60).

MY JOYOUS DESPAIR

My Joyous Despair contains many of the signature markings of an author’s first novel. Not in the sense that it seems amateurish—not at all. It is actually a rather concise and successful novel. However, compared to Guðmundur Andri’s later novels it is rather simplistic, in particular in terms of its style and plotting. Suffice it to say that it is a traditional love story about a guy who doesn’t get the girl. Still, the novel sets the scene for Guðmundur Andri’s oeuvre, especially in terms of its protagonist; an aimless young man going through an emotional crisis, who carries in his heart writerly ambitions that never come to fruition. This type of character appears again and again in Guðmundur Andri’s later novels, which will be addressed below. The novel’s style is rather simple, as befits its plot. It is told in a first-person past tense by the protagonist himself, who is looking back over his life at the winter when he undertook Icelandic studies at university. The benefits of hindsight give the novel a humorous and ironic tone throughout:

In the lobby, I wiped my feet on a black rubber mat. I thought to myself: Here I am, wiping my feet on a black rubber mat that has been tread by many of the nation’s cultural colossuses. I was enthralled, this was ceremonial occasion. Then I shook it off. Murmured: “brrr,” but only softly, so as not to bring down the mood. I walked along the hallway. There was no one there, nothing but silence. The silence felt charged with something—something noble. (p. 7-8)

Here, the protagonist describes his first day as an Icelandic Studies student and his first visit to the sanctity of the Árnagarður building at the University of Iceland. The ironic humour of this extract is typical for the novel, and in fact for the whole of Guðmundur Andri’s oeuvre. Despite this, My Joyous Despair contains some chapters that are more poetic and serious—which is unsurprising as the focal point of the novel is the protagonist’s life in a time of crisis.

The novel’s main storyline concerns the crisis that Egill—the protagonist—is going through as he seeks a new direction in life after having split up with his childhood sweetheart. By moving to Reykjavík, Egill is following in the footsteps of his ex-girlfriend Katrín, who left the village where they grew up before him. However, his attempts at reconciliation come far too late for their relationship to be anything more than a memory. His purposes in studying Icelandic are unclear; at times it seems that he merely wishes to procure a student loan: “I had grown tired of fumbling around with pointless jobs and had been dreaming of having a student loan for a long time” (p. 10). However, a couple of other motivators seem to weigh more heavily upon him: “I went south because of the stories. They consumed me, and I had to learn how to put them down on paper. Of course, I originally went south to see what was going on with me and Katrín, whether something was happening to us” (p. 45). Egill is a kind of half-way writer; he has countless ideas for stories but never manages to put them down on paper. His studies don’t seem to help him grapple with his story ideas, which are just as aimless as he himself. He becomes smitten with a girl who is also undertaking Icelandic Studies. Her name is Sigríður, and she captures Egill’s attention on the first day of school. Later, in fall, they begin a relationship. However, she is in fact married to another man the whole time, and eventually breaks things off with Egill. It turns out that she never actually stopped seeing her ex-husband, and finally decides to go back to him. This tragic love story is interlaced with descriptions of classroom events and scenes from the students’ social lives. These incidents are at times hilarious, and Guðmundur Andri’s ironic wit is in top form during those descriptions.

Another subplot that is intertwined with the love story concerns Egill’s attempts at mastering the stories that consume him. It’s interesting to note that the story that the reader of My Joyous Despair is reading is in fact told by Egill himself, and so it must be assumed that he has finally managed to put at least one of his stories down on paper: “Since I was a little boy, I’ve looked at the people around me and tried to imagine their stories—not the actual people but only their stories. A person’s story is composed of the events of their life as seen by someone else, not as see by themselves, and I was interested in those events.” (p. 43). Egill’s definition of a person’s story is interesting in that he himself is telling his own story, which he is observing from a distance. He is looking at himself and the incidents of his life as they appear from his perspective, trying to view them as they were seen by others at the time when they actually occurred.

THE ICELANDIC DREAM

Guðmundur Andri’s second novel, The Icelandic Dream (1991), was nominated for the Icelandic Literary Prize. It garnered a lot of attention, not the least because upon its publication it addressed some of the apprehensions about contemporary Icelandic society that were being voiced at the time. It brought forth concerns over debt, bankruptcy and the personal tragedies that may result from such issues. It might be rather limiting to say that the story is only bound up with this particular period in Icelandic history, as it actually looks at three different periods in Iceland’s post-WWII history. While it mostly takes place in the nineteen-nineties, the novel also covers Iceland’s post-war years, when vast numbers of people moved from the countryside into the city, and Icelandic society became very smitten with the glory of the nation’s recently declared independence. It also looks at the nineteen-seventies, when the children of the nuevo-riche inhabitants of Reykjavík began enjoying the benefits of their parents’ toils; e.g. by having the opportunity to attend secondary schools.

As with his previous novel, Guðmundur Andri uses a first-person narrative in The Icelandic Dream. The story is framed in such a way that its narrator, Hrafn, is sitting in his living room, sipping whisky-on-the-rocks and reminiscing about the past. Key elements of this process can be seen in phrases such as: “I remember”; “It’s all happening inside my head” and “I’m trying to visualize it.” These phrases establish the inner time frame of the narrative—along with the clinking of the ice in his whisky: “I’m sitting here, thinking about taking a sip of whisky, but before I do I lift the glass to my ear and shake it a little bit. It makes a “klirr-klirr” noise.” (p. 66). Most of the story takes place inside the narrator’s head. The narrative is mostly composed of guesses and attempts at filling in the gaps in Hrafn’s own life and the life of his best friend, Kjartan. What the narrator remembers and tries to visualise—the events taking place inside his head—might be called the novel’s inner time frame—as separate from the novel’s outer time frame, which acts as a framing device for the narrative. The sound of the ice tinkling in the glass acts as a measurement of the novel’s outer time frame, as the “klirr-klirr” noise that the ice makes in the glass has been silenced by the end of the book.

Mainly, the aforementioned three separate time periods offer a comparison of the different generations inhabiting each period; a theme commonly found in Guðmundur Andri’s later novels, which will be discussed below. Hrafn and Kjartan are members of the youngest generation; the one raised by the settlers who moved to Reykjavík after the war. The story mostly concerns Hrafn’s dealings with Kjartan and Kjartan’s family, although attention is also given to Hrafn’s own family. These two family histories come together in a surprising way at the end of the novel, as it becomes evident that Hrafn and Kjartan share the same father. A similar merging also takes place in the two men’s lives, as Hrafn’s wife is Kjartan’s ex-girlfriend and the mother of Kjartan’s child. Thus, the two friends’ fates are intertwined throughout their whole lives.

Father and son Sigurður and Kjartan are in many ways the main characters of the narrative that Hrafn brings forth in his nightlong rumination, which is accompanied by the tinkling of ice in his whisky. Sigurður is a member of the generation that moved from the country to the city at the end of WWII, turning his back on the countryside’s farming society and its values: “He left because of everything his father had taught him, the values that his father had tried to instil in him to stop him going south. In taking on those values, he ended up defying his father’s will. As long as he could remember he had been consumed by the values that his father had instilled in him” (p. 38). Sigurður’s adventures in the city seem promising at first: he gains a diploma as an electrician and becomes an employer but is eventually betrayed by his business partner. After that, his misfortunes pile up, and his life starts to revolve around his drinking and the bitterness of his crushed dreams. Kjartan is very adamant that he is not going to repeat his father’s mistakes. He seems to have a very promising life ahead of himself due to his immense powers of persuasion and his considerable abilities as a craftsman. Despite Kjartan’s eagerness to succeed where his father failed—i.e. by becoming independent and free—it seems that the two of them might share the same curse. The power and productivity that is such an integral part of both father and son seems to be intertwined with their self-destructive nature, which nothing can escape.

Over the span of the long evening that Hrafn sits and reminisces about the lives of these two men—as well as his own—he ends up comparing his parents’ generation with his and Kjartan’s generation. However, he also takes stock of his and Kjartan’s lives; their transition from young and radical students to grown men who are afflicted by the harsh realities of life; their struggle to maintain a career and home life when the exuberance of youth has faded. This is perhaps particularly evident in three separate events which are contrasted in the text despite taking place at different intervals. The first is Sigurður’s experience of taking part in the festivities on Iceland’s independence day in 1944. However, as Hrafn sets the scene, Sigurður isn’t so much a participant as an observer, standing on the side line and looking on:

As it appears in my head: it’s as if the Icelandic upper crust is making a spectacle of itself, parading in front of the rest of the nation, which is standing there on the sidewalk. They’re telling the people: be proud of us, trust us. There goes the president, the bishop and all the other dignitaries. The ones that you’d usually find up on stage during military parades in other countries, watching while the nation’s favoured sons are marched by them. Here they are the ones putting on a parade (p. 88).

The second incident occurs during the Keflavík March, which was a protest march against Iceland’s inclusion in NATO and the resulting US military base stationed in Keflavík. Hrafn and Kjartan take part in the march along with other young radicals:

When we marched back into Reykjavík, elated by our victory, shouting together in a single voice, what I couldn’t understand was all the people standing on the pavement and sitting in their cars. Icelanders who you would never see marching in the street, shouting slogans or letting loose in any other way—they [...] looked at us and just saw a bunch of kids. To them, we were the ones in the inner circle; the privileged youth. They were the outsiders, the ones that had slaved and risked everything for us and then been dismissed by us [...] We were the educated classes on parade. The upper crust of the future, making a spectacle of itself, showing its power, its superiority.

[...]

To those standing aside and looking on, we were exactly the same as the people that Sigurður Sigurðsson had looked upon with admiration on the 17th of June 1946, on the anniversary of the Reykjavík Junior College (p. 145).

These generations, these three events, these three time periods are then drawn together in a scene described by Hrafn and compared to the other two events in such a way that the contrast becomes almost comical—or at least it becomes evident that a lot has changed, and a different set of values is now in vogue:

We got up early, the little family in the big house, me and Helga and little Óli, and we dressed in our traditional clothing: jogging suits. After a brief warm up we went down to Lækjartorg square to take part in the festivities. This was not a parade of students and the upper crust of the future, like in 1946, nor was it a protest march of kids and the new, educated upper class, like in 1974. No, this was a marathon (p. 171).

It’s interesting to note that Hrafn shares many similarities with Egill, the narrator of My Joyous Despair, as he also harbours dreams of becoming a writer; dreams that never come to fruition: “Well, I had turned thirty four without writing the book that I meant to write when life would really begin, I hadn’t bothered to write that book nor any other book that had offered itself to me” (p. 74). Furthermore, both narrators have managed to capture their own story after the events, even if it is not in the physical form of a book. The entire narrative takes place inside their heads—to coin the phrase used by Hrafn himself.

THE TRIP TO ICELAND

Guðmundur Andri’s third novel, The Trip to Iceland, was published in 1996 and was also nominated for the Icelandic Literary Prize. It is a historical novel that tells of a poetic English aristocrat who travels to Iceland in the late 19th century in the company of his friend, a scientist named Cameron who also hails from the English upper classes. Their travel companion is an Icelander called Jón Hólm, who travels with them from England and acts as their guide in Iceland. Young English aristocrats commonly took such journeys in those days, to Iceland as well as other places. Guðmundur Andri uses a wealth of sources written about such trips, along with more recent historical research. However, it’s not just the search for adventure that the young Englishman is seeking; he is also searching for himself. This motivation for his self-discovery is twofold: On the one hand, he is seeking his origins, as his mother is Icelandic, and he is to some extent raised by Jón Hólm. The aged Icelander left Iceland to settle in England some 30 years ago, entering into the service of the young Englishman’s father after the conclusion of the latter’s journey in Iceland. On the other hand, he is haunted by a terrible events that takes place shortly before he leaves for his journey, and which weighs heavily upon him.

All of Guðmundur Andri’s novels have in common their superb structure. They are intricately arranged in such a way that their structure reflects their storyline. This is very apparent in The Trip to Iceland, where the novel’s structure is actually directly related to the storyline. The story is mostly built out of the young aristocrat’s journal passages, although it also includes fragments of the folktale narrative about the Bjarnastaðir Demon, which is given to the young man by the aged Jón shortly before the old man passes away. Naturally, this tale has some relevance, as it is intrinsically linked to the journey itself as well as the young aristocrat’s past. A novel like The Trip to Iceland must certainly be the result of vast amounts of research, which expertly applied in the construction this epistolary novel. This is pointed out by Eiríkur Guðmundsson in his review of the novel: “Although the structure of the novel is that of a journal, it is first and foremost a novel, or rather a successful mingling of the two forms: one form overrules the other without dispensing with it entirely” (p. 112 TMM 1997:1).

As in The Icelandic Dream, the story develops on two separate fronts: Firstly, in the real-time writing of the journal itself; i.e. during the journey. Secondly, through events from the distant as well as recent past, as the narrator struggles with his own past in England and the events that took place shortly before he set sail, as well as his origins in Iceland, which concern his father’s journey to the country some thirty years earlier. The novel might be considered a logical continuation of the themes explored in The Icelandic Dream. Not only due to its technical similarities, as it is also concerned with a historical period during which the foundations are being laid for modern Icelandic society. In the book, modernity has arrived in Iceland, as can be seen in the aristocrats’ compatriot, the Icelander Jón Hólm, who harbours dreams of a new Iceland. His vision of a glorious future for Iceland calls to mind similar themes that can be found in the writings of Icelandic poet and politician Einar Benediktsson:

The Icelander seemed the very height of respectability, sitting there in his tailored suit, blonde and tall, with tenderly waxed moustaches and his beautiful, winding pipe. Looking severe, he made it clear to me that he intended to move to Iceland within five years. There he would strive to establish a British-Icelandic steamship company. I could see that Cameron was rolling his eyes, as if to indicate that he was getting tired of the Icelander’s passionate sermons about this mission of his (p. 65).

However, this enterprising dreamer might also have something in common with Garðar Hólm, the protagonist of Nobel Laureate Halldór Laxnsess’s novel The Fish Can Sing, as in both novels the sermons that these characters give on the might of the Icelandic nation and its victories all across the world seem confined to the realm of fantasy. At least the two young Englishman tend to doubt him, each in their own way. Cameron because of his limited faith in this primitive nation in the North, and the protagonist because he would rather hold on to the myth of the noble and pure Nordic spirit, which he hopes will be preserved in the Icelandic nation. There are other elements to remind the reader that modern Icelandic society is merely around the corner, even if the two Englishmen don’t see them as signs of modernity—especially Cameron, who is rather smitten with the theories of Charles Darwin. For example, during their time in Reykjavík the two English aristocrats run into politician Jón Sigurðsson—the leader of the Icelandic independence movement—as well as the national poet Matthías Jochumsson. In the eyes of the Englishmen, these great cultural figures of 19th century Iceland don’t seem particularly inspiring. For one, Jón Sigurðsson merely appears to be some crazy old man. “During our visit, his face held a smirk that seemed rather idiotic to me, truth be told” (p. 96-97). And Matthías Jochumsson has more or less stopped composing poetry: “I only compose memorial poems for others, as there is not much else to write about around here” (p. 106).

As all good historical novels do, The Trip to Iceland draws into focus many aspects of contemporary culture through its revision of the past. For one, it is inevitable to draw some comparison between the personality of the 19th century Icelanders found in the novel and characteristics commonly attributed to Icelandic people of today. You might say that these characteristics have been brought even more to the forefront by recent events, more so than upon the book’s publication in the nineteen-nineties. It’s interesting to consider the ideas concerning the nature of 19th century Iceland which are brought forth in the novel and compare them with modern perceptions of Iceland in the 21st century. In the protagonist’s perspective, the mythos of Icelanders being a nation that is in touch with nature as well as the origins of Nordic society and democracy is given great value. This perspective is founded on the interplay of literature and mythology, as well as the desire for establishing a North-European cultural identity.

Although the novel takes the perspective of an outsider, as its narrator is English, these themes are still discernible today. Today, such depictions endure, although their roles have been reversed—as the myth is upheld through idealistic imagery and the market forces that make use of this vision of the country and the nation.

A FORCE OF MERCY

The Trip to Iceland, The Icelandic Dream and My Joyous Despair all address generational gaps, throwing light on how a younger generation tries to define itself as being of a different ilk than the preceding generation, despite never fully managing to escape being compared to their forebears. This takes shape in a variety of ways in the first three novels and is particularly apparent in the latter two novels— as mentioned above. A Force of Mercy, Guðmundur Andri’s fourth novel, also looks at generational differences. A Force of Mercy has much in common with The Icelandic Dream, as they both take place in the same time period and both focus on the first and second generations of recently urbanised Icelanders; new inhabitants of the city who relocated to Reykjavík after WWII. However, in A Force of Mercy a third generation is added: the grandchildren of these new settlers of Reykjavík. The story takes place in the Vogar neighbourhood in Reykjavík:

For a time, it housed the countryside’s largest refugee camp; residents who had decided to become Southern-Icelanders, had moved down south and flocked to this easternmost fringes of the city because that’s where they could find land, moors and farms. [...] Without realizing it, they had developed a new identity: they were East-siders; Reykjavík citizens whose gait still spoke of a familiarity with fields and moors (p. 68-69).

The story is focused on husband and wife Baldur and Katrín, their friend Geiri and their children, Sigurlinni and Sunneva. Baldur, Katrín and Geiri are all born after 1950 and are thus a part of the second generation of the “refugee camp”, but the three of them are also all descended from families that moved to Reykjavík from the eastern part of the country. In the background is the generation that went before; the early settlers, especially Baldur’s father, former politician Einar Egilsen. A particular era of Icelandic political history is at the forefront of the novel; i.e. the story of the Icelandic left, with Baldur picking up his father’s mantle and becoming the great new hope of the political party knows as The Movement. Einar himself is an old-school communist who has never budged an inch in his views: “He never floundered. Even when everything seemed to be falling down around him and the faults in his views on how the worlds was structured became ever more obvious, he never reconsidered anything—what was more despicable than reconsidering one’s views?” (p. 109).

Baldur and Geiri start taking part in The Movement’s work at a young age. Their first meeting takes place one winter when Geiri is invited to live with Baldur’s parents while he awaits the start of his studies overseas. From that day onward, the two of them are inseparable; perfect friends who still always feel as if they “didn’t meet up as much as they’d like to, and even when they did meet more often they never talked for long enough, and when they talked for longer they both felt that they rarely ever talked about anything that really mattered” (p. 26). Both remain active members of The Movement, but Baldur is eventually forced out of the party’s leadership, despite his many decades on the frontlines. Geiri, however, withdraws from The Movement on his own initiative, partly for reasons to do with his eccentric hatred of American populism but also due to personal reasons—romantic complications, in fact.

Katrín is a leftist at heart and is “in her heart of hearts opposed to anyone actually owning anything—with the very idea of absolute and continuous economic growth going directly against her idea of a prosperous life” (p. 19). Even so, she has long ago given up on politics—if she ever actually cared for them to begin with. After working as a teacher for a decade, she resigns to study theology and eventually becomes a priest: “It was actually not a great change for her, going from teacher to priest. Each job was concerned with providing guidance. In both cases she had to stand before people, get them to listen to her and teach them how to learn things by themselves” (p. 19).

Neither Sigurlinni nor Sunneva take on their parents’ values. They have everything they need but at the same time only need to worry about themselves and their closest surroundings: “the first existential crisis generation” (p. 47). In the hopes of being able to retire in ten years’ time, Sigurlinni finds an income by selling vast amounts of cosmetic products in secret. He hides the source of his wealth from his parents, along with everything else that doesn’t fit with his socialist upbringing; e.g. his self-help books, his gold chains and diet cokes and especially the song he wrote for the European Song Contest. Sunneva is just as unenthusiastic about her parents’ political ideals. She leads an aimless life, lost in emotional turmoil while trying to decide between two men; a Swedish bohemian named Jan, who she meets while staying in London to apply for an acting school, and simple and easy-going Þórður, who is undertaking a degree in politics.

The perspective is divided up fairly evenly between the characters and gradually reveals each one of them to the reader. Although the same narrative voice remains throughout, the tone of the narration fluctuates depending on which character is taking centre stage each time. This shift in the narration depending on point of view can be clearly seen in a chapter that focuses on Katrín. The Tuesday morning in question, she is on her way to a coffee house when she suddenly starts seeing ghosts; something that hasn’t happened to her since she was a child. The whole chapter is marked by her clairvoyance, not the least the way the narrative uses colours to describe her surroundings: “This should have been a cosy day with mild colours” (p. 80). Her experience of the world is reflected through colour. The whole morning the yellow colour of the wallpaper in her parents’ home—which is intimately connected to her childhood experiences of clairvoyance—is draped over her eyes.

The structure of A Force of Mercy is not unlike that of The Icelandic Dream and The Trip to Iceland. That is not to say that these novels follow a formula, or all have the same format, but they have a certain narrative approach in common. As mentioned above, the time frame of the narrative in The Icelandic Dream is twofold. That is: there is a main narrative, which takes place in the past, and a framing narrative, which happens in real time as the narrator reminisces about past events while the ice in his whisky clinks and melts. A similar structure can be found in A Force of Mercy, which begins on a Monday evening and ends approximately 24 hours later. While the limited “real-time” of the narration passes by, readers become acquainted with the novel’s characters, especially by bearing witness to the past events of their lives. These events are brought forth incrementally by the invisible narrator, who has full access to the thoughts of the novel’s characters but never actually takes part in the proceedings.

In A Force of Mercy Guðmundur Andri’s technique of narrating a novel using two separate time frames is more or less perfected. The framing story gradually drives the reader onwards with its sense of foreboding. At the same time, the past is revealed incrementally, providing insights into the characters’ backgrounds and lives.

IN CONCLUSION

Guðmundur Andri’s particular skill lies in his language and style and the mixture of the two within his novels. In My Joyous Despair, The Icelandic Dream and A Force of Mercy, Guðmundur Andri mixes ordinary, contemporary language with the stylistic language of fiction. Spoken language and literary language come together as one, at times almost without the reader realizing it. In The Trip to Iceland, different styles of language also come together; contemporary language mixes with 19th century dialect in such a natural manner that the reader experiences both even though the difference between the two is notable.

More often than not, Guðmundur Andri’s protagonists are confused young men who struggle under the demands and expectations of previous generations. This theme can clearly be seen in his first novel, My Joyous Despair, as protagonist and narrator Egill is consumed with malaise and refuses to follow his father’s footsteps and become a doctor—nor is he willing to accept the fate most readily available to young men in seaside towns by becoming a fisherman. Neither one of the two protagonists of The Icelandic Dream manages to find a foothold in life, and their childhood dreams never come to fruition. They are beset with guilt when contemplating the generation that preceded them: Kjartan is haunted by his father’s mistakes, which he himself is doomed to repeat, and Hrafn is left with a similar sense of guilt. The protagonist of The Trip to Iceland also struggles under the weight of previous generations, alongside his friend Cameron who remarks to him: “You and me [...] we own too much and therefore never get to own anything [...] You can’t take over your father’s company because you would run it into the ground in no time [...] You are completely useless. And so am I. I am incapable of taking over my father’s lands” (p. 63). Sigurlinni shares this outlook, a hundred years later: “His dad had been deeply involved with The Movement at his age; tackling the state of the world, doing something that mattered, changing things. What had he done? What had he become? He had gotten a degree in dental technology” (p. 43). His father, on the other hand, spends most of his life bridging the gap between the beliefs of his own father, the old-guard communist Einar Egilsen, and the contemporary outlook of The Movement political party.

Another interesting factor that connects all of Guðmundur Andri’s novels is that all his protagonists are failed writers or artists. The writerly ambitions of Egill, the protagonist of My Joyous Despair, were mentioned above but despite these ambitions he never manages to capture all the stories that consume him. In The Icelandic Dream, Hrafn also intends to become a writer but never manages to do so. He could also have become a musician but can’t seem to manage that either—according to him because it might have been something he would have been able to do without feeling shame. The journal keeper who supposedly jots down The Trip to Iceland is also a failed poet, as his friend Cameron cruelly points out: “you can’t even write poetry, even though you’re always trying to do so” (p. 63). One of the goals of the trip to Iceland is to write a poetic cycle about the country; an ambition that seems just as unlikely as Egill’s plan of undertaking Icelandic studies in order to capture the stories that consume him. The only artistic creation that these characters manage is the story itself, the very one that the reader is enjoying. In A Force of Mercy, Baldur and his son Sigurlinni also belong to this flock. Both are artists that have stifled their own creativity due to external circumstances and the demands placed upon them by their surroundings. Neither dares to step forth and put their name on their work, so that in both cases the fruits of their labour wind up in a web of deceit. Sigurlinni hides his passion for simplistic pop hits from his family, though he has actually gone as far as sending one of his songs to the European Song Contest. His father writes crime novels under a pseudonym and makes paintings in the guise of an undiscovered naïvist folk artist.

Calling these three novels by Guðmundur Andri a trilogy might be a stretch, but they certainly share a multitude of thematic connections. In a way, all of his novels are an exploration of Icelandic society. This is especially true in the case of his last three novels, as they explicitly deal with specific aspects of Icelandic history and certain tumultuous periods of social change which are then examined from different perspectives. It is sometimes said that the novel form is an exploration of human society. If there was ever a case for making such a claim it would be in relation to the works of Guðmundur Andri—his last three novels in particular. It might seem overly simplistic, or perhaps an outrageous generalisation, but by taking stock of the lives and fates of Icelanders Guðmundur Andri’s novels offer a dissection of the origins and development of contemporary Icelandic society.

© Ingi Björn Guðnason, 2007

Awards

2013 - The National Broadcasting Service´s Writer´s Fund

2008 - Reykjavík City Children´s Literature Prize: Bangsímon (Winnie the Pooh) by A. A. Milne (for the translation)

1991 - DV Cultural Prize for literature: Íslenski draumurinn (The Icelandic Dream)

Nominations

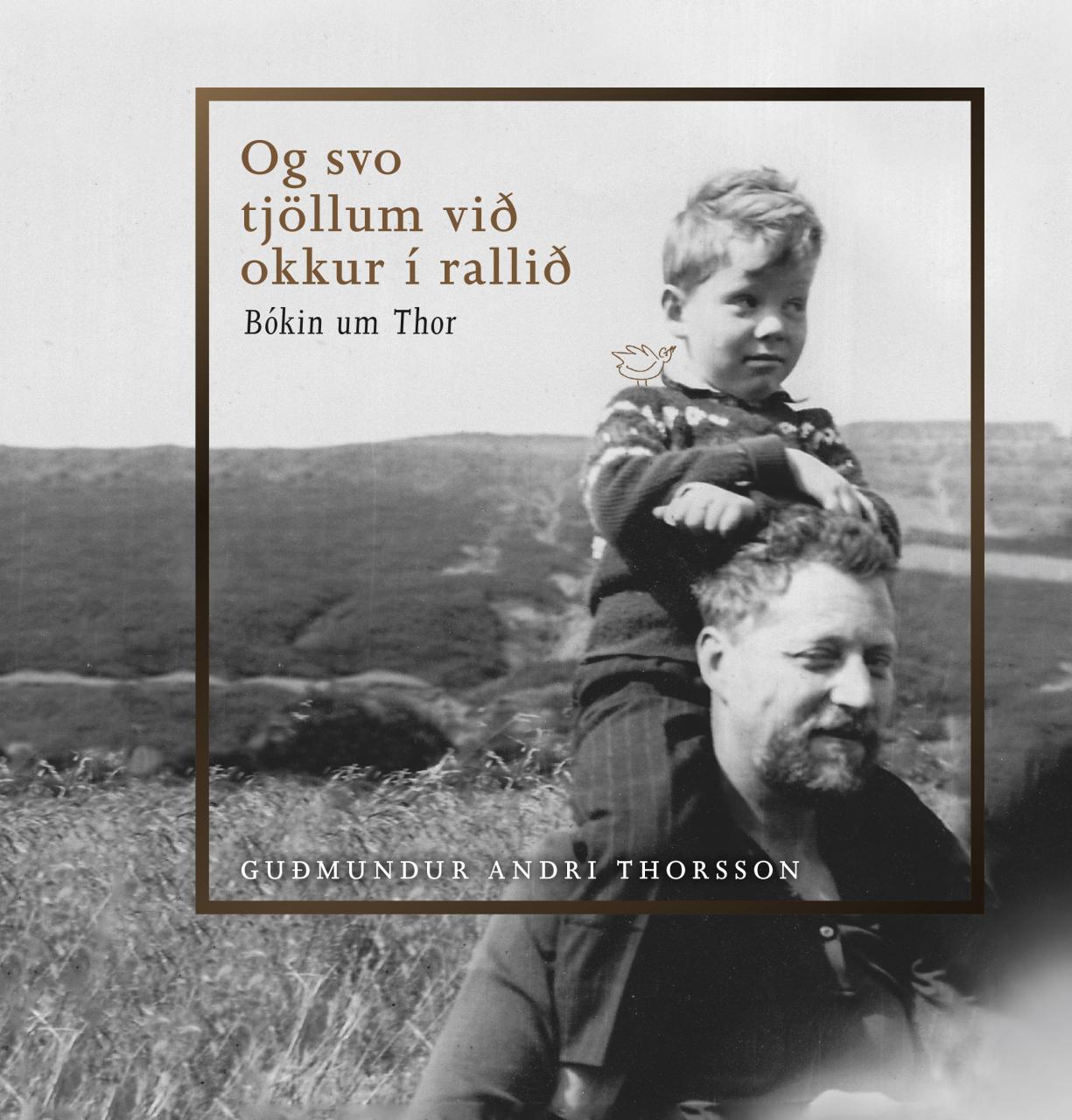

2015 - The DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Og svo tjöllum við okkur í rallið: bókin um Thor (The Book About Thor)

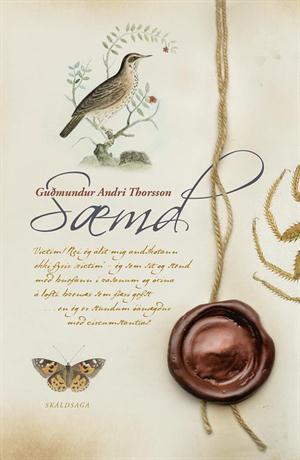

2013 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Sæmd (Honor)

2013 - The Nordic Council´s Literature Prize: Valeyrarvalsinn (The Waltz of Valeyri)

1996 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Íslandsförin (Journey to Iceland)

1991 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Íslenski draumurinn (The Icelandic Dream)

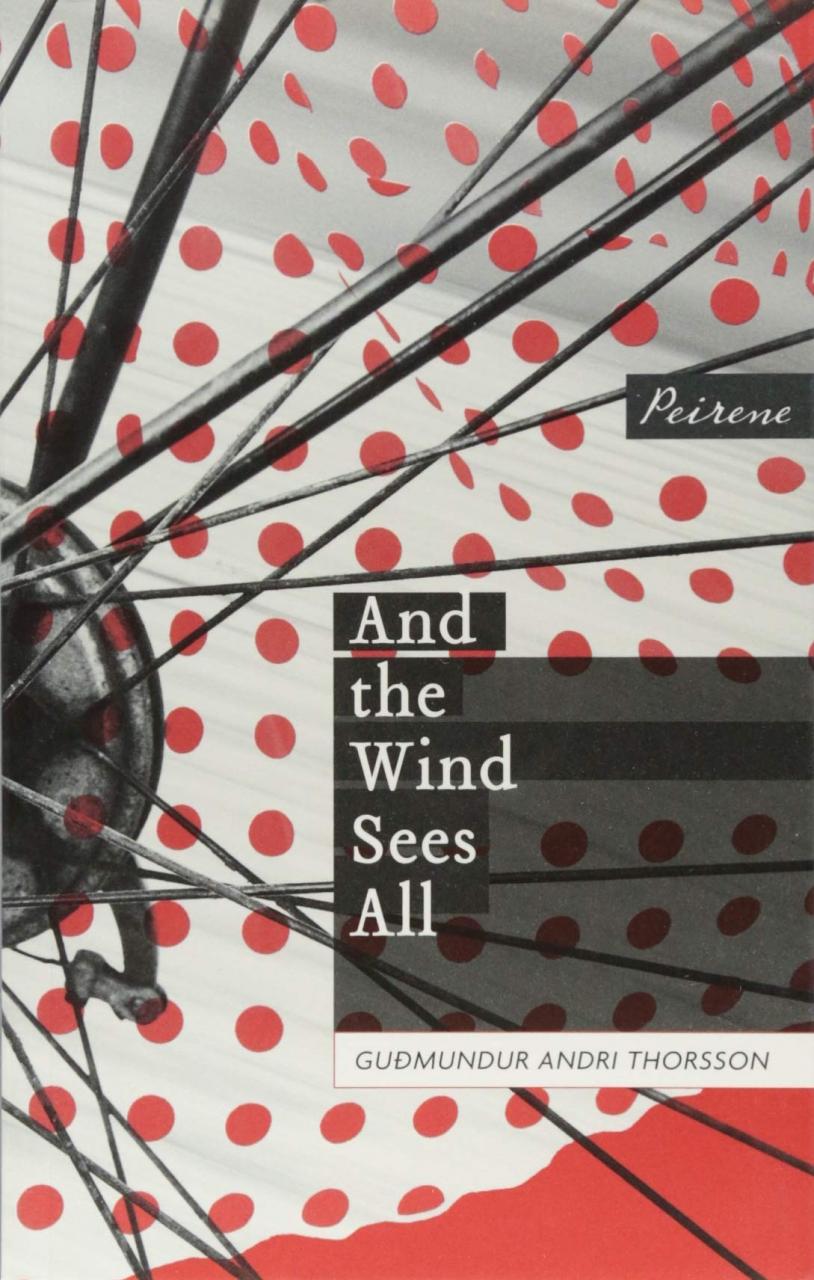

And the Wind Sees All

Read more

Og svo tjöllum við okkur í rallið: bókin um Thor (The Book on Thor)

Read more

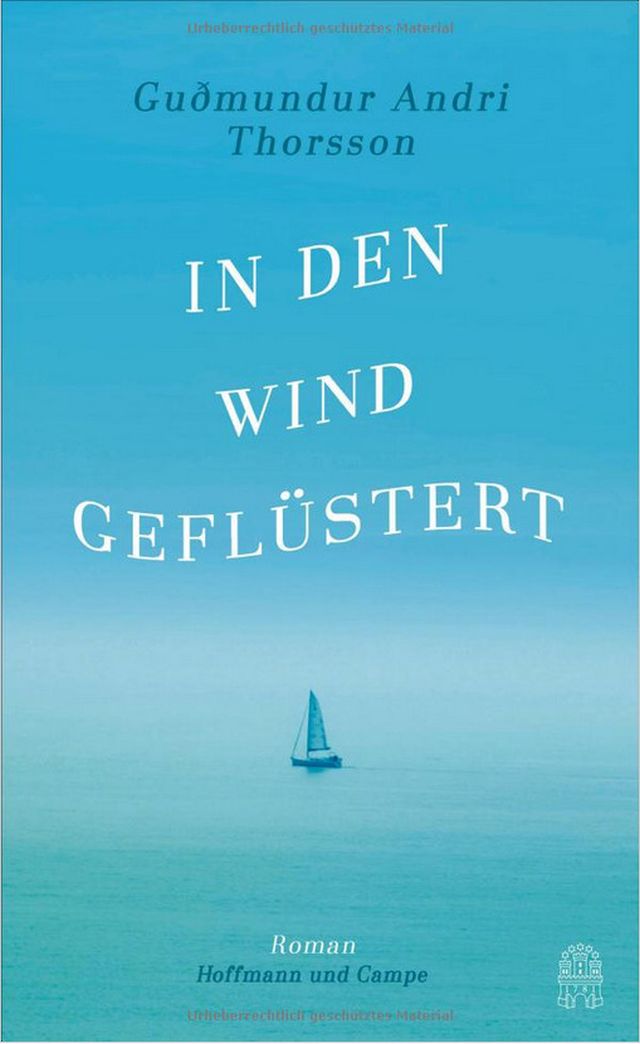

In den Wind geflüstert

Read more

Sæmd (Honor)

Read more

Valeyrarvalsinn (The waltz of Valeyri)

Read more

Segðu mömmu að mér líði vel (Tell Mom I´m Doing Fine)

Read more

Íslensk bókmenntasaga IV (Icelandic Literary History IV)

Read more

Íslensk bókmenntasaga V (Icelandic Literary History V)

Read more

Náðarkraftur (A Force of Mercy)

Read more

Húsið á Bangsahorni

Read more

Bangsímon

Read more

Tveir húsvagnar (Two Caravans)

Read more

Stutt ágrip af sögu traktorsins á úkraínsku (A Short History of Tractors in Ukranian)

Read more

Allir saman nú (All Together Now)

Read moreGettu hve mikið ég elska þig (Guess How Much I Love You)

Read more

Á refilstigum (A Savage Place)

Read more

Guð forði barninu (God Save the Child)

Read more