Bio

Hallgrímur Helgason was born on February 18th 1959 in Reykjavík. He studied at the Art Academy of Iceland from 1979-1980, and at the Art Academy of Munich from 1981-1982. Since then, he has worked as both a visual artist and writer.

His first novel, Hella, was published in 1990, followed by several others, as well as plays, collections of poetry and translations. His novel 101 Reykjavik (1996) drew immediate attention and was subsequently translated throughout Scandinavia, Europe, and England. In 1999 it was nominated for the Nordic Council´s Literary Award. A movie of the book, directed by Baltasar Kormákur, one of Iceland´s leading film makers, was produced in 2000 and released worldwide. Baltasar also adapted Hallgrímur’s novel, Þetta er allt að koma (Almost There) for the stage. It premiered at the National Theatre of Iceland, directed by Baltasar, in 2004. He has received a number of awards for his work, such as the Icelandic Literature Prize.

In addition to novels and poetry, Hallgrímur´s diverse body of work includes plays for both radio and theatre, essays on society and culture for various newspapers, as well as performing stand-up comedy. As a visual artist, Hallgrímur has had numerous solo exhibitions in Iceland and abroad, such as in Boston, New York, Paris, and Malmö; and has been included in a large number of collective exhibitions across the globe.

From the Author

April Fool

In the first half of the twentieth century telephones were not widespread in rural Iceland. In many parts of the country there was only a telephone on one farm in each parish. People often had to be fetched long distances to answer the phone. At one farm at the foot of Eyjafjöll there was a telephone. A pauper had been assigned a home there; he was known as Pal. He wasn’t exactly bright and one of the jobs he was given was to take “telephone messages” on horseback to nearby farms. Pal was illiterate. Once, on the first day of April, Pal was sent off with a telephone message. He had to ride a long way, including crossing two unbridged rivers, before he finally reached the farm, walked up to the farmhouse and greeted the people there. He was welcomed and served with cakes and coffee, and he handed the farmer’s wife the note with the telephone message on it. The note said: “April Fool.”

It can take a long time to write a novel. The author needs to travel a long way on his poetic steed before he reaches his readers. But in the end he makes it to the farm, and is generally welcomed at first. Then he hands over his book. The farmer’s wife reads the title on the cover and asks the author what it means. It is difficult to find an answer. The author is illiterate. He was just sent over to the next farm with a message, a message he does not understand himself. Because if he did he would never have gone. And then we would never have had a good story to tell. But the question is: Who sent him? In my case the answer is: “April Fool.”

The story of Pal is taken from Gestir og grónar götur (Guests and Grown Tracks) by Þórður Tómasson from Skógar, Mál og mynd, 2000.

Hallgrímur Helgason, 2001

Translated by Bernard Scudder

About the Author

Made in Iceland: The literary works of Hallgrímur Helgason

The public image of Hallgrímur Helgason is getting more complex as he gets increasing exposure on the Icelandic cultural scene. It is impossible to sort the columnist or the stand-up comedian from the poet, and the painter or the playwright from the novelist. In the same way it can be difficult for some people to sort the image from the man himself, as Helgason has to a great extent made good use of the possibilities of the advances in the Icelandic media. He has taken part in shaping a new and powerful Icelandic culture that is increasingly central and is in many ways the result of a prosperous economy. Helgason is very critical of the nation and its culture and he airs his views in articles, regular columns and interviews. He finds faults with institutes like the Icelandic Broadcasting Company and other official cultural institutions. He dislikes critics (especially literary critics), and he does not have high regard for Becket, modernity, minimalism, modernist poetry, The Shopping Channel, the Japanese haiku, East-European cultural influences and the Central Left Coalition Party. One could go on at some length. The list of all the things Helgason hates is very long and the attitude of the artist is reminiscent of the angry young men who gained literary fame in post-war Britain.

Not many have responded to Helgason’s criticism that is surprising, considering his presence on the Icelandic cultural scene. Helgason’s attempts to liven up the Icelandic cultural scene are worthy of praise but he might also be overly enthusiastic. For many he might be like the neighbour’s hypersensitive car alarm which is activated every time someone passes by.

Culture is a nag

Many aspects in the work of Helgason can be connected to the so-called postmodern condition. Its origins have been traced to the 1960s and 1970s when British pop music became an international cultural phenomenon for the first time. In postmodernism the border between high culture and popular culture is blurred. Postmodernism attacks the idea that culture belongs to the chosen few and it strives to remove culture from the pedestal where the modernists allegedly placed it. The development of capitalism in democratic Western societies has given birth to mass culture, but its representatives demand to be taken seriously as creators of art. Postmodern attitude often turns against the idea of universities’, or other cultural institutions’, possessiveness of knowledge. In the wake of a richly varied media, the expansion of the web, the information revolution and other electronic communication developments, the scholar no longer has the task of informing the citizens. Helgason himself touches on this in the short paper “Enskan er þjóðlegri” (English is more nationalistic):

The scholars who controlled the nations’ ideological existence into the mid 1980s: What became of them? One by one they became quiet, removed themselves from newspapers and news bulletins […] Live broadcasts replace sharply worded articles.

In Postmodernism image is paramount, thus making youth and looks of the utmost importance. In the spirit of this idea Helgason has glorified Icelandic youth and pointed out that it’s “the kids who liven up the city” and are “making a name for Reykjavík”. In postmodern art the emphasis is placed on a certain look, style and manifestation, but originality, form and material depth are secondary. Postmodernism is a culture within quotation marks. Banality and the superficial are put forward in an artistic light and the lack of depth is glorified. It can possibly be stated that the aim is to highlight the condition of things instead of creating a meaning where there is no meaning. Helgason’s comments on his novel Þetta er allt að koma show an affinity with those ideas:

With this book I want to bring literature closer to the people – bring it down to earth, even lower, down to the gutter, by allowing myself everything, nonsense, games, tastelessness and the latest gossip, mixing it with known events and, of course, pure fiction. Not many things are as boring as “well made” and “quality” books.

A critical attitude prevails in postmodernism, lack of faith in values and even nihilism are voiced. Sometimes it is said that unlike modernism that refers to culture, postmodernism “eats” culture.

Culture has its applications and is recycled. Various styles and art forms are thus often mixed together. The so-called Generation X, but Helgason has often been called its father figure in Iceland, has also been called the recycling generation. Helgason has himself said that the era of recycling is upon us and that poetry needs to be rejuvenated. It is obsolete. Helgason’s book of poetry Ljóðmæli 1978 – 1998 bears the hallmark of this recycling. There he writes poetry in the style of many well-known Icelandic poets and some poems are pure imitations.

The search for Jónas

Helgason’s poetics are radical and aim to make poetry a more central literary medium than it is now in the era of modern poetry. One of Helgason’s better known articles “Ljóðið er halt og gengur með hækju” [Poetry limps and walks with a crutch] was published in the magazine Fjölnir in 1997. It states the author’s opinion of the condition of modern Icelandic poetry. In the article Helgason criticises the influences of the Japanese haiku in Icelandic poetry and states that the poets are incapable of transferring the poetry to an Icelandic reality, language and nature: “The word “prairie” ["slétta"] has a foreign ring to it since there are no prairies in this country […]; in Icelandic it is called a meadow, meadows, field, pasture, moorland, swamp and in the worst case lowlands, flatland, flat country or plain but never prairie.” Helgason wants to awaken a more nationalistic direction in poetry and use rhyme and alliteration because he thinks that modern poetry has run its course: “What is more old-fashioned than a traditional formless poem?”

Helgason is consistent to his statements and Ljóðmæli 1978-1998 is true to his ideas of the condition of poetry every step of the way.

Most of the poems in Ljóðmæli are use rhyme and as in nineteenth-century books of poetry there are poems on travel and patriotism, commemorative poems, birthday poems, four line stanzas and longer epic poems. In this book an effort is made to bring the poetry closer to the reality of the Icelandic public (of the younger generation) by using colloquialism, adopted English words and alluding to popular culture. Some of the poems could be lyrics to a pop song and there is even a translation of a rap song by Ice-T, “Með rími ég rek þig á hol” [I run you through with rhyme]. Other poems take place in well known clubs in Reykjavík, bars or cafés in Iceland and abroad. There is a description of bohemian lifestyles in Paris and Rome and poems about love, relationships, courtship and flings are plentiful in the book. English is mixed in with Icelandic which is part of the attempt to write poetry about Icelandic society the way it is today, and Helgason has said that English has become part of Icelandic nationality.

One of the nation’s great poets, Jónas Hallgrímsson (1807-1845), is a favourite with Helgason and his poems “Ísland” and “Ferðalok” [Journey’s end] could claim to be the recycled versions of their namesakes by Jónas.

Leiddi ég þig á Mokka

svo lítið bar á,

vöfðum vindlinga.

Brosa blómavarir

blikna poppstjörnur,

ást í brjósti býr.

He also honours Jónas in the dramatised poem “Fyrir utan og innan á Bíóbarnum eða leitin að Jónasi Hallgrímssyni” [Outside and inside the bar or the search for Jónas Hallgrímsson]. Thus cultural heritage belongs to the ordinary public and becomes a part of everyday life. It is also possible to note parallels with the articles Helgason wrote for the magazine Fjölnir and the harsh critique Jónas Hallgrímsson published on Tistransrímur [The Ballads of Tistran] by Sigurður Breiðfjörð in that very same magazine over að century and a half earlier. At the time when Hallgrímsson wrote his critique, the ballads where quite central to Icelandic poetry and Breiðfjörð one of the most loved poets of the nation.

For Helgason, the form does not have the same meaning as it did for the poetry of Hallgrímsson who revolutionised Icelandic poetry by introducing foreign meter. Helgason’s revolution comes in the form of style, content and language rather than form which is meant to be a way for the poetry to reach the masses. Helgason has said that in order to sell books of poetry they must appeal to the “ordinary and those innocent in the ways of poetry”. The form of the poems in Ljóðmæli refers to traditional culture, whereas the language and setting connect them to the everyday reality of Icelandic youth who speak English, drink, party, have sex, listen to pop music and rap music and travel abroad.

Raising glasses with the poets

In a similar vein, Helgason has specific ideas on Icelandic Theatre. In a lecture he gave in the City Theatre of Reykjavík in the autumn of 2000 he propounded his ideas. He emphasises the importance of the theatre being closely linked to the Icelandic audience, how it must have energy in abundance, be influential and entertaining. The theatre needs to shed its pompousness the death of all artistic creativity according to Helgason: “I have long dreamed of a new breed of theatre which is closer to bar culture, stand-up comedy, beer swilling and natural and normal city life, without being vulgar.” Helgason puts forward the ironic theory that the theatre’s pompousness stems from the fact that “theatregoers in Iceland are of the average age of 67”. This vision seems to be tainted by the youth centred view that is common amongst those of the postmodern persuasion where the young and beautiful body is paramount. Helgason wants the theatre as well as poetry to be contemporary and national in character and shed some light on the present.

The source of the play Skáldanótt [Night of the poets] was the aforementioned poem from Ljóðmæli “Fyrir utan og inni á Bíóbarnum eða leitin að Jónasi Hallgrímssyni” [Outside and inside the bar or the search for Jónas Hallgrímsson]. The play takes place during the annual so-called ’night of the poets’ when the nation’s great poets come to life. That night the young people in the play speak in rhyme due to their love of poetry. They try to show their poems to the famous poets, take their photographs, pester them for interviews or want to experience the event. Among the great poets are Jónas Hallgrímsson, Einar Benediktsson, Benedikt Gröndal and Steinn Steinarr and they do not speak in rhyme and have little interest in the poetry of the young people, but are more interested in contemporary politics, gossip and trying to get their leg over. Towards the end of the play a fight breaks out among the poets where the young poets compete for the title of the greatest poet. Skáldanótt [Night of the poets] bears witness to the fact that Helgason is trying to move the theatre closer to the bar. The play takes place to a great extent both inside and outside bars [in central Reykjavík] and the finale, the fight of the poets, takes place in Lækjartorg [central Reykjavík] at four o’clock in the morning. Fighting, singing, drunkenness and the search for sex belong to the Night of the poets:

Allir þessir þá þramma um

þyrstir í líf í Miðbænum.

á “Skáldanótt” er skálað við

skáldin aftur í heiðinn sið

og þá kveðjum við okkar hversdagshjal,

í kvæðum bindum okkar tal

því ástin blómstrar um bjarta nótt.[All those pounding the pavements stinking of piss

pant for the life of downtown bliss.

During the “Night of the poets” we drink and dally

around the ancient poets we rally

and bid adieu to the mundane mother tongue,

our language in heavy meter is hung

because love blossoms in the light night.]

The young people’s excitement has more to do with their intense interest in poetry than in the nightlife as such. On the Night of the poets the glasses are filled with poetic mead. Other plays by Helgason such as Rúm fyrir einn [The single bed], which was premiered in the Lunch Time Theatre of Iðnó in May 2001, refers to the social debate about sexual politics. In Rúm fyrir einn the male anxiety of not being able to satisfy a woman sexually is portrayed in að comic light when the male characters, Ari and Svanur who both have slept with the same woman, Jóhanna, cannot figure out when she is faking an orgasm. The masculinity of men is in decline because of the increased influence of women in society. In an unpublished play by Helgason Alzheimer in Love, that can be found on his web site, one can clearly see the existential crisis of the male population. The philanderer Dóri is both loved and hated by women. His relations with women lead to a lovesickness. He is banged up in various institutions that are controlled by women and their persecutions undermine his sanity in ever decreasing circles. The words of Dóri are maybe descriptive of many a man’s troubled state of mind: “I’m past the sell-by-date, man on his last legs, in twenty minutes I will start to go mouldy”.

Oedipus in Reykjavík

The work of Helgason Helgason is highly varied and it can be said that between books there are jumps in style and content, and many critics have made a point of the fact that one of the characteristics of the author is how he rejuvenates the language and stretches the boundaries of the normal written language in Icelandic. Hella, Helgason’s first published book is, however, in many ways different from his other works. There is not much of the unorthodox colloquialism, phrases and foreign words which characterise his other works and the reader’s attention is directed toward the story’s rather unusual point of view which describes minutely in a (seemingly) neutral manner the daily life of a young girl in a small village in the south of Iceland. In Þetta er allt að koma, however, the narrative style has turned ironic as that book is a caricature of the autobiographical format. The language is borrowed from gossip publications, glossy magazines and the media and the whole subject matter of the book is constantly made fun of. 101 Reykjavík goes, without a doubt, furthest in the renewal of the language where the narrative is mediated through the television addict and layabout Hlynur Björn who does little besides making up words which reflect his passionless existence.

Hella is the story of a fourteen-year-old girl, Helga Dröfn, who lives a monotonous life in a small town. The narrative strives to be neutral, not to pass any judgements, and the thoughts of the characters are not described. The narrative style is reminiscent of a camera recording accurately the life in the tiny village just as it is. In one summer Helga Dröfn changes from child to woman, starts to work in a kiosk, meets new boys, starts to drink, goes to race meetings, develops a crush on Biggi, her great grandmother dies and she loses her virginity.

The camera lens of the narrative is not quite as neutral as it seems because the changes the girl goes through are linked with the outer environment of the story. There is an emphasis on the psychological and physiological changes that Helga goes through when she loses her virginity. In the scene before that incident Helga is watching her younger sister sleep: “She sees herself sleeping peacefully in a child’s head on the soft duvet, sees the look on her own face the way it really is, in the beginning completely clean and unsullied by anything from outside, ideas, emotions or hopes. She sees her own face and strokes it carefully, treats it nicely. Finally she bends down and kisses her sister good night, kisses this part of herself, says her goodbye.”

Here Helga is saying goodbye to the child and innocence in her but the sexual experience that comes later initiates her into society as a sexual being. The tumults in Helga’s life have their parallels in the earthquakes and the expected volcanic eruption. Near the end of the story mount Hekla finally erupts and the mountain’s molten lava corresponds with the heat between Helga and Biggi who “do not see this tiny spark which lights up in the fog, hot and passionate, like a small kiss.”

Þetta er allt að koma is the biography of the fictional singer and actress Ragnheiður Birna interspersed with quotations from herself, her mother, friends, relatives and bedfellows, on her life, work and character.

These quotations could well be extracts from interviews in glossy magazines. The narrative is distant, ironic and as we are told of the life of Ragnheiður, she is simultaneously mocked relentlessly. The story makes fun of talentless Icelandic artists who do not have to make a great effort to achieve fame. Kristján B. Jónasson points out how the story revolves around “the victory of the bourgeois mediocrity.”

Ragnheiður is devoid of artistic abilities but she is good at publicising herself. She sleeps with the right men if the opportunity presents itself, gets her exploits written about in Morgunblaðið and has no problems with nudity. One of her greater victories is when she, with other busty beauties, sings topless for Arnold Schwartzenegger in Las Vegas:

The big moment had passed and Ragnheiður Birna was flushed with relief, full of the satisfaction that comes with the fulfilment of ambition, when a dream is made real. The make-up on her face had to suffer for the feeling of having made it. In her own way she has made it in America!

The incident which makes Ragnheiður famous in Iceland is when she falls badly from a horse whilst filming Hefndir haugbúans [Revenge of the grave-mound dweller] where she has the role of Melkorka the slave-girl. Although she has to relinquish the role she becomes a celebrity and a star in Iceland: “ On the table there was the weekend edition of DV with a colour photo of Ragga on the cover, smiling in a wheelchair […] “Risked everything”.

101 Reykjavík is about the 34-year-old Hlynur who lives with his divorced mother in Reykjavík, he’s unemployed and applies himself thoroughly to the nightlife of downtown Reykjavík. When his mother comes out as a lesbian his life is made more complicated because he has slept with her girlfriend, Lolla. Hlynur is the centre of the story’s chain of events and the story is conveyed through his thoughts and his experience of the surroundings. The story tackles the mass media consumption of the main protagonist and the effects of the world wide web, television and porn-films-gaping and the clubbing and drug taking, have on his consciousness. Hlynur has an emotional- and passionless existence, he has no dreams, has no duties, does not subscribe to any moral values and takes no responsibility of his own life. He has neither respect for life or death: “I will be dead after I die and I was dead before I was born. Life is the intermission from death. You can’t be dead all the time.” Eiríkur Guðmundsson states that Hlynur “can neither enjoy the sinful and lusty lifestyle nor is there a glittering death awaiting him.” The only thing Hlynur has to fill his days are endless word games, remarks, comments he uses to explain his existence, to pass the time or to fill some void: “My life in sentences. Life sentences.”

101 Reykjavík is based on Shakespeare’s play about Hamlet and Hlynur has many a convoluted version of the famous prince’s speeches. Many of the characters are modelled on the characters of Hamlet and the storyline is a rough version of the play as well. Unlike Hamlet, Hlynur cannot die. Possibly because he is not sure whether he is dead or alive: “I think I might possibly have kicked the bucket. I think I might possibly be dead for real.” Hlynur’s fear of castration does something to shake his apathy but that also refers to the legend of King Oedipus and from there to Freud’s interpretation of the neurosis implied by the story. Hlynur commits metaphorical incest by sleeping with Lolla and that act triggers his oedipal neurosis. Hamlet’s famous speech “To be or not to be” become Hlynur’s nightmarish and sexually charged delusional rant about his mother he delivers while having sex with Lolla:

To do it or not to do it. To come or not to come, that’s questionable. Should I keep going as if nothing had happened, enjoy it, or let the doubt go forth like a fireman with his hose along my veins and hose down my flaming blood cells. Mother. Consideration. I am her son.

Hlynur’s fear of castration manifests itself in his self-description as an extinct species. He is useless, “dangling a very obsolete tool hither and thither.” His crisis is thus also directed toward his manhood and the fear that women like Lolla the lesbian will take over the world, have children from sperm banks, have masculine power despite being female. 101 Reykjavík is a modern, spirited tragedy where nothing happens outside the head of Hlynur. The family stay together, Hlynur does not pluck his eyes out, does not die, kills neither himself nor others.

The story does not offer a solution to Hlynur’s existential crisis. He can only express himself with words and sentences that have limited context. Words and events flow endlessly and accidentally form a context as if he might be doped or half awake and half asleep with the television left on: “Channel 74: A crime of passion in Sydney. I accidentally fall asleep with this playing. I dream a meteor heading for my head.”

Alda Björk Valdimarsdóttir, 2001.

Translated by Dagur Gunnarsson.

Articles

Articles

Cribb, Victoria Ann: “Hallgrímur Helgason in the spotlight” (interview)

Iceland review 2000, no. 38, pp. 76-77

Jón Yngvi Jóhannsson: “Billedkunstnerne kommmer : er islandsk litteratur en happening eller en installation? = The coming of the visual artists : is Icelandic literature a happening or an istallation?

Nordisk litteratur 2001, pp. 72-75

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. x, 466, 584

Awards

2021 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Sextíu kíló af kjaftshöggum (Sixty Kilos of Punches)

2021 - L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettre - French Order of Arts and Letters

2018 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Sextíu kíló af sólskini (Sixty Kilos of Sunshine)

2017 – The RÚV Writer‘s Fund

2017 – The Icelandic Translators‘ Prize: Óþelló (Othello) by William Shakespeare

2004 – Reykjavík City Artist

2001 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Höfundur Íslands (The Author of Iceland)

2000 – The DV cultural prize for playwrighting

1999 – Second Prize in Playwright competition for Hádegisleikhúsið (The Lunch-Hour Theatre): 1000 eyja sósa (1000 Island Dressing)

Nominations

2015 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Sjóveikur í München (Seasick in Münich)

2013 – The Nordic Council´s Literature Prize: Konan við 1000°

2011 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Konan við 1000° (The Woman at 1000°)

2007 – The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize: Rokland

2005 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Rokland (Windyland)

1999 – The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize: 101 Reykjavík

Woman at 1.000 Degrees

Read more

Fiskur af himni (Fish from the Sky)

Read more

Lukka (Lucky)

Read more

Sjóveikur í München (Seasick in München)

Read more

Ljóð í leiðinni: skáld um Reykjavík (Poetry to Go: Poets on Reykjavík)

Read more

Kobieta w 1000°C : na podstawie wspomnień Herbjorg Maríi Bjornsson

Read more

Kvinden ved 1000°

Read more

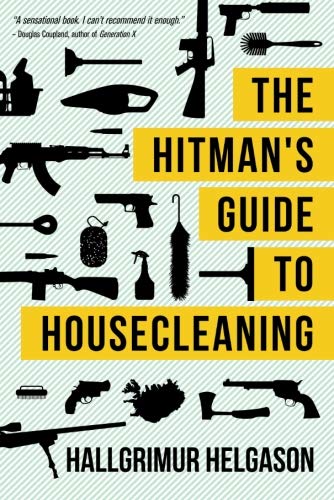

The Hitman‘s guide to housecleaning

Read more

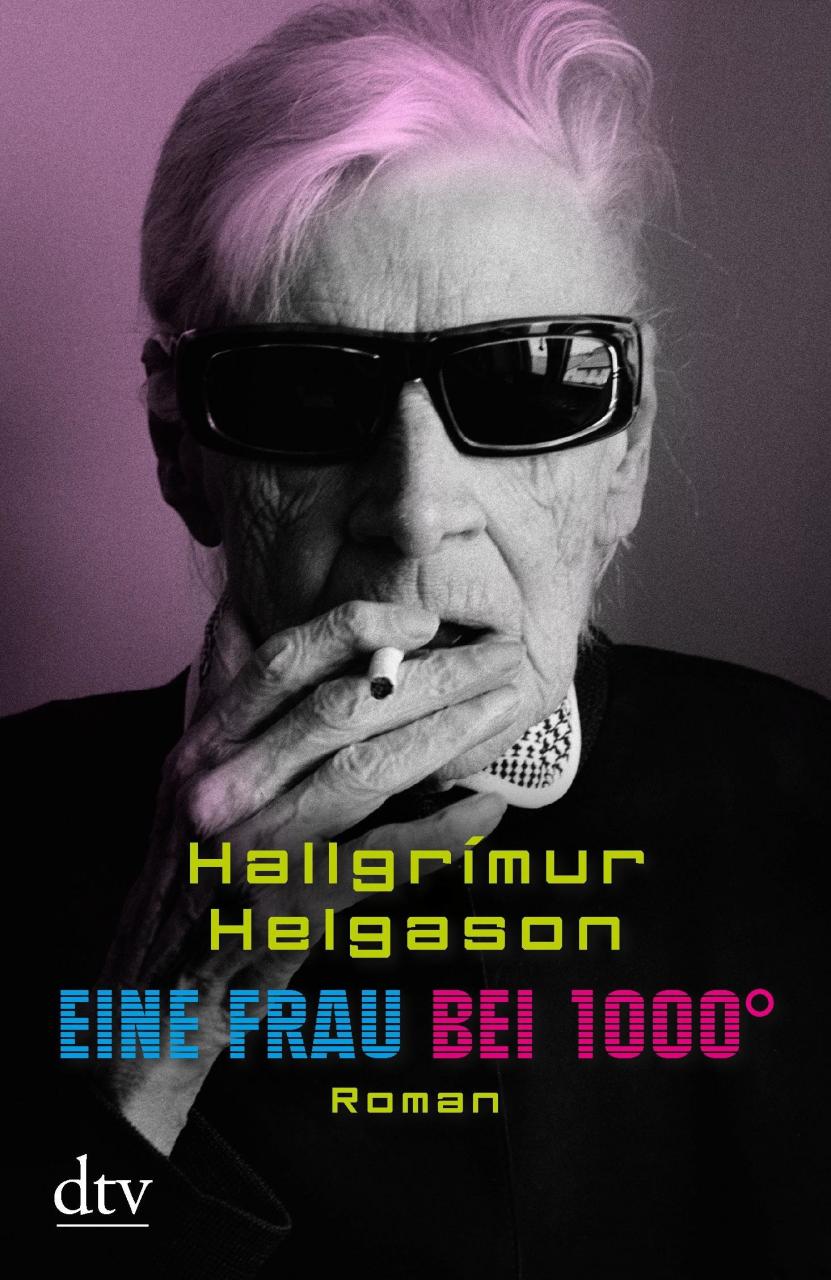

Eine Frau bei 1000°: Aus den Memoiren der Herbjörg María Björnsson

Read more