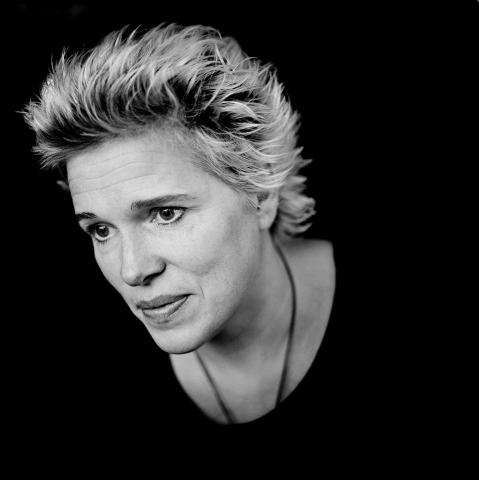

Bio

Ingunn Snædal was born in East-Iceland in 1971. She graduated from The Iceland University College of Education in 1996, studied Irish at NUIG in Ireland from 1996-97 and Icelandic studies from 2006-08. She has lived in a number of places outside Iceland, such as Ireland, Denmark, Spain, Costa Rica, and Mexico. In Iceland, Ingunn has worked as a teacher, a proof-reader, a cook on a road-construction team, a waitress, a petrol station attendant, a delivery girl, a mailman, a seasonal worker at herring fishing, a cleaner, a copywriter and a private tutor on top of her writing.

Ingunn’s first book of poetry, Á heitu malbiki (On Hot Asphalt), was published in 1995. Since then she has published more poetry books. The first, Guðlausir menn – hugleiðingar um jökulvatn og ást (Godless People – Thoughts on Glacial Water and Love) won Reykjavík City’s poetry award in 2006 and was also nominated for The Icelandic Literature Prize. Her third book, Komin til að vera, nóttin (Here to Stay, the Night) received the Icelandic Women´s Literary Prize in 2010. Ingunn's poems have been published in collections in Iceland and abroad, and translated into other languaes, such as English, Swedish, Turkish and German. In addition to writing poetry, Ingunn works as a translator of literature.

From the Author

Why Do I Write?

The simplest answer is because I enjoy it. Words have always fascinated me, their interplay and effect. Thoughts are created by a bundle of juicy words, like trout fastened together by the tails, hanging on a stick.

Is the world of words different from that of our reality? Of course it is. And of course it is not. Words bring to us what is already within us, even if it is nowhere else to be found. It is in a way wonderful that mere words on paper can make people laugh and cry. Emotions created by fiction play a big role in people’s moral and emotional upbringing; at least that is true in my case. Many of my most valued fellow travelers in life are fictional characters. Not surprisingly, I have more in common with many of them than those with warm blood in their veins. “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?” said Dumbledore ever so truthfully.

Because it is fun?

In order to keep grammar that is disappearing alive? The subjunctive, for example?

I wrote my first poem when I was around eight years old. It was in fact a kind of libelous verse about one of my neighbors and to this day I do not understand this forwardness that was totally out of an otherwise shy girl’s character. This poem was also different from my later poetry in other ways; it had rhyme and alliteration which I haven’t used much since, not being very good at it. My childhood has nevertheless been a great inspiration for my writing, as is often the case with writers. There are still traces of the child’s freshness in my life, like a hint of taste on the tongue, the fresh thoughts of a girl who sees the world for the first time.

In my teenage years, I wrote to keep my senses, like so many others. Everything I could not say went into notebooks that piled up, decorated with Wham and Duran Duran stickers. I felt I was unique in the world; that no one felt like I did and thus that my experience was a priceless treasure on paper. When I found out that every single line was a cliché and a terribly overused sentiment, I threw all the books away and didn’t write a word for ten years. Speaking of taking yourself too seriously.

Do I write because I am a middle child, and as such fairly co-dependent?

Because through writing I can create myself again? A more pleasant, likeable me?

In poetry you can play on so many fine cords that are common to all of us - and find the warmth that they bring. They are like some elixir that cheers you up and makes you healthier and stronger, all at once.

In order to play?

To find an outlet for all the ugly feelings, those that I may even be ashamed of?

A wise woman has said that people write because something is wrong with them.

Something is wrong with all of us.

Ingunn Snædal, May 2009.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Travelling with Poems

íslenskt landslag

að hálfu leyti himinn

hinn helmingurinn

minning[Icelandic landscape

half sky

the other half

a memory]

Ingunn Snædal’s third book of poetry ends with this poem. The book is called Í fjarveru trjáa (In the Absence of Trees), and it tells of a road trip in Iceland, which the poems show as a mixture of landscape and memories. This blend of travel descriptions and memories is a distinctive feature in more of Ingunn’s poetry, her two latest books, Guðlausir menn – hugleiðingar um jökulvatn og ást (Godless Men – Thoughts About Glacial Water and Love) and Í fjarveru trjáa, are both poetry-travelogues. The latter carries the subtitle “road poems.” Even if travel isn’t as much a characteristic feature in the first book, its title is Á heitu malbiki (On Hot Pavement). The journey can also be seen in a symbolic meaning, as traditionally in poetry, since the love poems in the first book are written for a man, but eleven years later, a woman is the subject of love in the second one. Thus, an interesting sense of life as a journey is created, for travel always involves some change, new experiences, as shown so well in the ever changing experience of nature and land in Í fjarveru trjáa.

Nature, the Icelandic landscape, plays a major role in Á heitu malbiki; even if the book mostly contains love poems, nature is close by, both as the subject and in the language of the love poems. Snow is shown as something soft and beautiful in “Fyrsti snjórinn” (First Snow) and “Snjókoma” (Snowfall); in the former “milky-white clouds / have fallen from the sky”. April 1st does not indicate spring, but more snow and in “Þrá” (Longing), nature writes poetry for the speaker. In the poem “Möðrudalur”, the mountain queen appears: “hundreds of years has she waited / for the fairy-prince // But all genuine princes are disgusted / by ancient, proud / queens.” The fairy-tale returns in the poem “Regn” (Rain), where the speaker is transformed into a mermaid: “I swim softly to the ocean / lightly flipping my tail.” The book’s title is taken from a poem called “Í Neskaupstað í maí 1995” (In Neskaupstaður in May 1995), where the pavement heats up in the sun so “steam rises from the wet street / as if the gods have / as a prank / put the underworld on fire.”

Love is the main subject of the book, and as in a travelogue, the story is about a journey through love, from bliss to distance and pain; contrary to many such love stories this one however ends well. The last poem “Náttflug” (Flying by Night) describes the beating of wings where “bitter thoughts / flutter away”. This is however not the only flight, the distance between the lovers is also described as flying in the poem “Fjarlægð” (Distance). In this poem, swans fly in formation and their singing is carried to the poem’s speaker from afar where she lays contently in her lover’s arms, but his thoughts are somewhere far away. The metaphor of nature can also describe love at its best, as in “Regnbogaljóð” (Rainbow Poem):

Í mildri blámóðu á heitu sumarkvöldi

brosir þú við mér mjúkum rauðum vörum

Gullin hárin á handleggjum þínum gældu við

uppbrettar peysuermar þegar við gengum í döggvotu

grasinu[In the mild blue mist of a hot summers’ night

you smile to me with your soft red lips

The golden hair on your arms caressed

the rolled-up sleeves as we walked in the dewy wet

grass]

Here, the lover’s connection is shown to be in perfect harmony with nature and the colour spectrum of the rainbow, from blue, red and yellow to the green grass.

“I want to write you a poem”

Eleven years passed until Ingunn sent forward her next book of poetry, and during this time many things have obviously happened in her life. It is not only love that has changed, time has also been well spent to polish and collect Ingunn’s poetic language. For this book, Guðlausir menn, she received the well deserved Tómas Guðmundsson Literature Prize, and two years later the third one, Í fjarveru trjáa, followed. What characterizes these two books is a strong whole, that makes these books stick in the reader’s mind, but also demands that she or he follow the poems all the way through. This type of a whole, that can be likened to ancient epic poems, has in fact been prominent in the poetry of young poets in Iceland in the past few years. The benefits of this whole is that the weaker poems are supported by those that are stronger, each one has its place in the thread that is being woven. The risk, on the other hand, is that if the overall picture is weak, the whole book can fall flat, in spite of strong poems here and there. This is not the fact in Ingunn’s case; she seems to have found a solution to the problem she puts forth in the first poem of her first book:

Halló

Mig langar að yrkja ykkur ljóð

úr öllum fallegustu orðunum sem ég þekki

í því eiga að veratúlípanar

fiðrildi

brönugrös

kotasæla

stjörnuhrap

vængasláttur

svefnþungi

skellibjöllur

maríutásurÉg sé ekki fyrir mér

í fljótu bragði

um hvað slíkt ljóð gæti fjallað[Hello

I want to write you a poem

with all the most beautiful words I know

it should containtulips

butterflies

orchids

mountain-dew

shooting stars

beating wings

drowsiness

loudmouths

mare’s tailI cannot picture

in a quick glance

what this poem could be about]

Rushing On

Although Ingunn’s second poetry book carries a long title: Guðlausir menn – hugleiðingar um jökulvatn og ást, it doesn’t look heavy or complicated at first sight. In fact the book can be said to contain only one poem in addition to a prologue; the poem “dauði, ferðalag og játning” (death, travel and confession). This poem is a kind of biography as well as being a travel story, the speaker is travelling through Iceland on the way to her grandmother’s funeral, and her brother and sister are in the car with her. She recalls her childhood with her grandparents, at the same time as she thinks about her siblings’ lives. In between in this long poem, there are shorter poems, a kind of refrain, text-message love poems and thoughts about news, relatives, and neighbours from the countryside. The country itself, the land, is a subject, both in the longer poem and the intervals. In a way, this is all familiar, the travel theme is a classic theme in poetry, love, nature and childhood memories as well; we also see a poem about a photograph, they seem to be a favourite with the poet (and it reminded me about the beautiful photograph-poems of Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir and Þóra Jónsdóttir).

But there is more to all of this – as poetry is always a bit tricky. Within this simplicity, these familiar themes, there is some freshness – slowly a world of movement, pictures, smell and sound is being drawn up. An example of a simple, but memorable picture is the poem XVII, the speaker is “bloody always” thinking about her loved one and wishes that she “could rest in that feeling / as in a hammock / safe and happy // I feel very happy in hammocks”. Here we move from a feeling of irritation to a feeling of safety, and it is connected to a physical experience and position, that of laying in a hammock and that is where we end up.

The structure of the book is very well done; the prologue-poem about being in distress sets the tone of a fine balance between humour and sorrow that characterizes the poems. This poem shows a fraction of a memory that seems to be from childhood. The speaker crosses a river and her feet get wet, as she doesn’t want to take the longer way and pass on the rocks: “when you are in distress and rush on it is lame to make a detour. A little bit like you are not distressed enough.” And then, the music continues on CDs that are played in the car, Radiohead, the Icelandic bands Ensími and Sigur Rós. Not only does the music set the tone, but also gives a feeling for time. The first poem starts thus: “Mosfellsbær, 67 km/hour / Radiohead, No Surprises on full blast / pass the road to Þingvellir / 85 km/hour / still Radiohead but another song and the volume down”. In another poem, we hear about the grandmother’s death, she passed away a week ago and the speaker has “had time to think about it” but has had a hard time taking it in “here down south / where nothing around me has stopped”. Death doesn’t become real until she is back home in the grandmother’s familiar surroundings, and then “the farewell is of course tomorrow”. The trip is manifold, it is measured in kilometres pr. hour, songs on a CD, a sense of surrounding and finally physical events like the closing of the casket, which is described thus: “lean forward / kiss grandma on her forehead / whisper say hello to grandpa”. The theme of death (and life leading up to it) as a journey is put forward in a simple and beautiful way, without any pretentiousness. The journey back home to take leave of the grandmother mirrors the old woman’s final trip, and she brings along regards to the grandfather.

The third journey is, as already mentioned, the journey of love. As the story progresses, a tale of separation and love towards a woman is revealed, and the emotional conflict it carries with it. The speaker moves out from her child “that repeatedly asks / classic questions / graduated in guilt”, “thirty-two and / and was losing / my human rights”. Following this poem is a more thorough description of this emotional turmoil, now in a humorous yet painful metaphoric language:

ég er skrímslavörður

svört og hvöss ólmast þau

á hvítu tjaldi hugans

vilja bíta migég er skrímslaveiðimaður

sit fyrir þeim

hvenær sem

tækifæri gefastég er skrímslavinur

gef þeim rúsínur

úr berum lófa

og sleppi lausum

til að éta mig

aftur[I am a monster-guard

black and edgy they rage

on the white screen of the mind

want to bite meI am a monster-hunter

lay in wait for them

whenever

I get the chanceI am a monster-friend

feed them raisins

from my open palm

and turn them lose

so they can eat me

again]

This very fine balance of humour and sorrow that Ingunn captures in her poems is especially powerful and makes it easy for the reader to walk into the world she creates in the book. The clear imagery also makes the poems accessible, not surprisingly the book became very popular and repeatedly sold out – something that is not common when it comes to poetry books. In a lecture about the Icelandic publication of the year, literary critic Þorgerður E. Sigurðardóttir said something to the effect that with this book, the poem reached more people than those it can call its own.

Seek it out

Þorgerður’s words indicate that not only does poetry deal with journeys as a subject matter, the poems themselves are on a journey – they can in fact be seen as a journey in themselves. The journey is still Ingunn’s subject matter in her latest book, Í fjarveru trjáa: vegaljóð (In the Absence of Trees: Road Poems). The fresh tone that characterizes Guðlausir menn is still there, although this book is in some ways more traditional in tone and structure. On the other hand, it can be pointed out that the whole is so strong in Guðlausir menn that it is difficult to pinpoint individual poems that reveal the atmosphere of the book. Although the sense of a whole is still to be found in Í fjarveru trjáa, the picture is not as complete, making individual poems more independent and secure on their own.

As indicated in the subtitle, the poems depict a road trip; the speaker travels around Iceland, main roads and off roads, and describes what she comes across, both within the car and without. The reader gets a sense of many travels and a variety of memories that are connected to places and experiences, in addition to getting to know the country itself through the poems. As such, the book could well be used as a kind of travel guide, similarly to the old travel guide described in the poem “í Húnavatnssýslu” (in Húnavatnssýsla), where:

hægt að fara í sund

í hálfhrundum

mosavöxnum laugum

og kaupa nesti í

löngu niðurlögðum

kaupfélögum[you can go swimming

in half-ruined

mossy pools

and buy lunch in

long since closed down

stores]

all of this if you “follow / a half-damaged road-guide / second edition”. These road-guides offer joyful errors and the feeling that you are taking part in something historic.

In this way, Ingunn’s poetry is a vibrant introduction to the country and its history, we meet ghosts and farmers, recollect old love affairs, sorrows and despair mixed up with laughter evoked by the fact that the hillocks in Vatnsdalur look so much like breasts. We find rules for hitchhikers and top-ten lists for this and that in nature, even though they most often count less than ten things, as in “topptíu fjöllin” (top ten mountains):

Lómagnúpur

Herðubreið

ekki hægt að toppa þau[Lómagnúpur

Herðubreið

can’t top them]

The top ten lists can even contain less than one thing, since in some cases the speaker feels that the reader must just make up her or his own mind – the beauty of nature can be a private matter, the waterfall being a case in point: “fossar eru persónulegir / blautir fallgjarnir / freistandi / hver og einn verður að eiga / sína í friði // ég ætla að þegja yfir mínum” [waterfalls are personal / wet free-falling / tempting / each and everyone needs to have / theirs for themselves // I am going to keep quiet about mine]. Here, nature becomes physical and pleasurable; in line with this, many places are connected with memories of bygone love.

This physical closeness with nature is also revealed in fun personifications, as in the poem “íslensk ferðalög IV” (Icelandic travel IV):

bregð kíki á fjallið

það kemur allt í einu nær

hallar sér upp að bílglugganum

eins og bóndi[point binoculars at the mountain

it suddenly comes closer

leans up against the car window

like a farmer]

In a poem about Kverkfjöll mountains, brisk nature guards appear as a kind of protectors of the land – in woollen sweaters and laced-up shoes, weather-beaten with scarves on their heads, and in the poem “Dettifoss” [Dettifoss is a waterfall], the speaker says she doesn’t trust water that you can’t hear: “here the water is more direct / doesn’t hide it’s intention / if you are not / careful at the edge”. The country is alive, ever changing, and nature isn’t only erotic – it is also somewhat frightening, as in the poem “Vatnsnes”:

í fjarveru trjáa grýtt slétta

með svört endalaus fjöll

á aðra höndhikandi sól þrykkir

flöktandi myndir

úr svörtum skuggum á jörðinastórir gráir steinar gera

göt í mistrið

alveg niður í fjörusjórinn dregur landið til sín

einn stein í einu[in the absence of trees a rocky plain

with black endless mountains

on one handa hesitant sun prints

fluttering pictures

from black shadows on the earthbig gray rocks make

holes in the mist

all the way down at the shorethe ocean pulls the land towards it

one rock at the time]

Man and nature then join hands in the aforementioned names of places and thoughts about maps and road-guides, or when the camping equipment breaks down as in the poem “ónýtt einnota grill” (a broken-down instant grill) where two ravens feast on barbeque-lamb, “still quite raw”. Fairytales are abundant, not least in the west fjords:

vestfirsk ævintýri

einu sinni voru þrír

risastórir vegagerðarmenn

sem ráku niður allar þessar

þriggja metra löngu stikurljónið sem sofnaði og

varð að fjalli fékk nafnið

Hestur til að fæla ekki

íbúana á brottinnst í Ísafjarðardjúpi

stendur hrörlegur

kastali sem undir

er botnlaus dýflissagegnum úrhellið kemur

gult skilti fljúgandi

og bendir í vestur

á þjóðveg 66[westfjord tales

Once upon a time three

giant road workers

stuck down all these

three metre long polesthe lion that fell asleep and

became a mountain was called

Horse as not to drive

the inhabitants awayin the heart of Ísafjarðardjúp

a run down

castle, underneath

a bottomless dungeonthrough the downpour

a yellow sign flying

pointing west

towards route 66]

Thus, Ingunn transforms the land into fairytales, be it the fumes from a hot pavement or impressive waterfalls. The land rushes forward in memories and stories like rich glacier water: Icelandic landscape that is “half sky” and “the other half a memory”.

© Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, 2009.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

Awards

2006 - The Tómas Guðmundsson Literature Prize: Guðlausir menn - hugleiðingar um jökulvatn og ást (Godless Men - Thoughts About Glacial Water and Love)

Nominations

2017 – The Icelandic Booksellers‘ Prize, best novel in Icelandic translation: Veisla í greninu (Fiesta en la madriguera) by Juan Pablo Villalobos, translation by Ingunn Snædal

2017 - The Ice Pick, for best translated crime novel: Hjónin við hliðina (The Couple Next Door) by Shari Lapena

2006 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Guðlausir menn - hugleiðingar um jökulvatn og ást (Godless Men - Thoughts About Glacial Water and Love)

Ljóðasafn: 1995-2015 (Collected Poetry: 1995-2015)

Read more

Skrautleg sæskrýmsli og aðrar lystisemdir : Hrikalega skrýtnar skepnur (A Colorful see creatures and other pleasures : Awesome odd animals)

Read more

Það sem ég hefði átt að segja næst (That I should have said next)

Read morePoems in Ny islandsk poesi

Read morePoems in Neue Lyrik aus Island

Read more

komin til að vera, nóttin (here to stay, the night)

Read morePoem in God i ord

Read more

í fjarveru trjáa: vegaljóð (in the absence of trees: road poems)

Read morePoems in Pilot: Debutantologi

Read more

Skandar og einhyrningaþjófurinn

Read moreVegna þess að einhyrningar tilheyra ekki ævintýrum, þeir eiga heima í martröðum.

Litla vínbókin: sérfræðingur á 24 tímum (The 24-Hour Wine Expert)

Read more

Harry Potter og bölvun barnsins (Harry Potter and the Cursed Child)

Read more

Allt eða ekkert (Everything, Everything)

Read more

Hinn litlausi Tsukuru Tazaki og pílagrímsár hans (Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage)

Read more

Árið sem tvær sekúndur bættust við tímann (Perfect)

Read more

Inferno

Read more

Hlaupið í skarðið (The Casual Vacancy)

Read moreHrikalega skrýtnar skepnur

Read more