Bio

Rúnar Helgi Vignisson was born on June 2, 1959 in Ísafjörður in the West-fjords. After graduating from highschool in 1978 he studied English and Icelandic at the University of Iceland, completing a B.A. degree in 1981. He studied French at the Université de Grenoble in 1981-1982 and German at Goethe Institut in Murnau and Freiburg in 1982-1983. During the winter months of 1985-1986 Rúnar Helgi stayed in Copenhagen writing. He completed a M.A. degree in Literary Theory from the University of Iowa in the United States in 1987, and continued studying and lecturing at the same university for the next two years. Rúnar Helgi lived in Chicago during the winter months of 1989-1990 and again in 1992-1993 and in Perth in Australia in 1991, working as a writer and doing research. Rúnar Helgi has been a part time lecturer at the University of Iceland from 1992. He has written numerous articles about literature and culture for newspapers and magazines and worked for the radio. Rúnar Helgi became Chairman of The Icelandic Translators Association in 2009.

Rúnar Helgi’s first novel, Ekkert slor (No Mean Thing), was published in 1984. Apart from novels he has written short stories and translated a large number of foreign works of fiction, among them books written by American, Australian and South-African authors. His novel, Nautnastuldur (Indulgence Denied), was nominated for the Icelandic Literature Award in 1990. Rúnar Helgi received The Icelandic Translator’s Award in 2005 for his translation of Boyhood by J.M. Coetze and The Reykjavík City Children’s Literature Award in 2006 for the translation of Sunwing by the Canadian author Kenneth Oppel.

Rúnar Helgi Vignisson lives in Garðabær in the greater Reykjavík area. He is married to Guðrún Guðmundardóttir and they have two sons.

Publisher: Græna húsið.

From the Author

Wallpaper of the Soul

When I was a boy in Skutulsfjörður the mountain hovered over me day and night, dangerous and caring at the same time. There I played, vented the need for adventure, picked berries, made dents in the snow, hiked, got hurt. The mountain was never the same from day to day, still always full of magic and wonders. Sometimes it became rebellious and started moving with roars high enough to make people freeze in their tracks, or even run for their lives. With its expressions, the mountain spoke out and made a point, sometimes for both of us. You could say that between us, a poetic connection existed – and still does – for the mountain is like a text, loaded with references and feelings.

At the edge of the mountain, the real-life-artist Sólon Guðmundsson once built a house he called Slúnkaríki. Sólon had this idea about architecture that the beautiful should face out, in order for as many people as possible to enjoy it. This perspective was played out in Slúnkaríki, but even to a further effect in a hut he later built for himself closer in. There, the corrugated iron faced in, but the wallpaper out. When Sólon was asked about this, his answer was: “Wallpaper is decorative my dear, and therefore it is natural to place it where it can be enjoyed by the biggest number of people.”

Just before my confirmation, I broke a shinbone while skiing on the mountain. During the time it took me to get better, I came in possession of my first typewriter and learned how to use it. The text that soon started flowing from this machine was the visible form of my thoughts, a kind of wallpaper. It is the lot of the author to turn himself inside out, in order to make others see what dwells within him.

In this sense, nature without and nature within come together in myself and in my oeuvre. The mountain-streams flow through my veins and their murmur burns on my lips, wherever I am in the world. The mountain has thus, in a certain understanding, written my books, whether they tell the story of Iceland’s 1000 years or human nature. And the translations that I have greatly enjoyed doing are at the same time my mountain hikes and my melting points – I wanted to see what would appear from underneath the snow, not least at the top of the mountain, and to gain some part in the glory.

Rúnar Helgi Vignisson, 2002.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Rúnar Helgi Vignisson: Translator, Author, Critic

I – Translator

As Rúnar Helgi has been a very active translator it seems fitting to start an essay about him with a few words about translations. Translations have sadly often been regarded as inferior work, both in traditional literary criticism and general discussion, and this way of thought is derived from romantic ideas of the Poet as genius. The Poet with a capital P has access to an elevated plane of thought which his or her work reflects and communicates to the more mundane reader. A translator gets in the way of this elevated communion and makes it harder for readers to imagine that the Poet is speaking directly to them. After all, the word was with God, not his amanuensis. Translations have however had an inestimable effect on creative endeavours in Iceland, as Ástráður Eysteinsson contends in his critical discussion of translations, Tvímæli. Translations, whether of classics or modern texts, introduce different ideas to isolated linguistic regions and thus contribute to a continuing regeneration of both language and discourse.

Critical afterwords to many of his translations indicate that Rúnar sets great store by knowing the entire oeuvre of the author whose work he translates. These essays further demonstrate that Rúnar possesses in-depth knowledge of the authors’ lives and the critique their work has received both in their country of origin and in international circles. While Rúnar has limited himself to translating work by twentieth century authors, the texts he has chosen to translate are not at all homogenous. He has translated short stories, novels and a children’s book by American, Canadian, Australian, South-African and British authors. Rúnar’s work as a translator has been well received and in particular he has gotten mention for rendering individual authors’ styles clearly in Icelandic. Thus the difference between the would-be refined conversation of Miss Thorne and simplistic comments made by Miss Peabody in Elizabeth Jolley’s Miss Peabody’s Inheritance are noticeably present in Rúnar’s translation. I do not have space here to compare many originals and translations, but the recently published Silverwing by Kenneth Oppel in Rúnar’s translation serves as an example of his mastery of the Icelandic language and his ability to engage creatively with what could be termed alien linguistic cultures, in this instance the echo vision of bats. His innovative use of language that borders on coining neologisms makes it easy for readers to visualise the bat’s world of shadow and sound. In translating both less known authors such as Oppel, as well as Nobel prize winners J.M. Coetzee and William Faulkner, Rúnar has helped ensure that Icelanders can access the best of world literature in their own language.

II – Author

Rúnar has also published a number of original texts, both novels and short stories. In his first book, Ekkert Slor (No Mean Thing, 1984), Rúnar explores life in a “typically Icelandic” (3) fishing village where day to day activities in the freezing plant, the main workplace, and the lives of the people who work there are dependant upon how the fishing goes. Significantly, the town is named Village, which suggests that neither the locale nor the people that inhabit it could be described as extraordinary. Johnnos, Janes, Toms and Maggies go to work, fall in and out of love and complain about the wages of land bound workers in fish processing. The Fishhouse provides a frame for both the story and the lives of Villagers, and the organisation of the text into short episodes reflects the fragmented life of the workers who rarely have time for quite contemplation or even to sleep. Brief chapters are further characterised by the same routines and repetitions that form the basis of life in Village: conversations about the weather and the daily buzz of the alarm clock. The narrator’s tone of voice at times becomes sarcastic, but always benevolently so; it remains the tone of voice of someone who realises that the story they are relating is hopelessly mundane but who nevertheless thinks such stories worth telling. The protagonists are ordinary in the extreme, and the lives they lead unexceptionable, but it is interesting to see how the author imagines individuals retaining their sanity over the conveyor belt, day after day, fish after thousandth fish. Even while poking gentle fun at unremarkable characters the narrator delivers a considered explication of the lives and thoughts of people he clearly respects. Their fate is neither exceptionable nor unique, but they populate the country and their stories are what constitute its saga.

Nautnastuldur (Indulgence Denied, 1990) is the story of Egill Grímsson, one of many young people to abandon Village in search of better things in the city. Egill himself did not appear in No Mean Thing, but the reader accompanies him back to Village for a visit to his parents and is briefly reunited with old acquaintances such as geezer Hehehehemmi. Not much has changed in Village – the Fishhouse remains the town’s epicentre, still painted as rosy pink as the daydreams of those who work there. Yet Egill’s dreams are far from rosy and they are just as far from coming true in Reykjavík as they were back in Village. Egill suffers from clinical depression and is desperately afraid of becoming an alcoholic like his father but has instead become addicted to sex, the only euphoria he knows. He is haunted by the ghosts of the past, appearing as silverfish Móri and Skotta, who manifest whenever Egill is having a particularly rough time, whether in his private life or at university. However, Egill’s saviour makes a timely appearance on Christmas Eve halfway through the book. J. C. himself moves into the apartment above Egill’s basement and introduces himself as Jens Christiansen, a homosexual Dane who makes it his mission to re-introduce a reluctant Egill into human society. The appearance of this unlikely saviour straight out of the closet reads as almost too fortuitous a coincidence and I wonder whether the timing and his name might not be intended as a joke on literary conventions? The narrator, always a haunting presence in No Mean Thing, becomes even more centralised here and in the afterword it transpires that narrator and protagonist Egill is actually the author of the novel. Or is he? The “afterword to the Icelandic edition” asks if the author couldn’t just as well have been called Helgi Rúnarsson or even Rúnar Helgi Vignisson. An important theme in Indulgence Denied is a discussion about the author and his position in and toward his work, about stories and histories and the curious fact that the Icelandic word ‘saga’ encompasses both story=narrative and story=history. Indulgence Denied, referring as it so often does to the Icelandic sagas, can because of this dual meaning be read as both/either a story about an Icelander and/or a story by an Icelander.

Divergent opinions on what it means to be an Icelander again come under discussion in Strandhögg (Incursions, 1993). One of its numerous narrators, an author, a figure usually present in Rúnar’s work, replies when asked that he writes about “being an Icelander” and disagrees with his questioner who states that this quality must simply be “in the blood” (192). The structure of Incursions is more complex than in Rúnar’s earlier novels and its organisation and form is more akin to a collection of short stories than a traditional novel. Short episodes resonate with and relate to each other, much like the protagonists, but without having any tangible common denominator such as the Fishhouse in No Mean Thing. The connection is nevertheless there: all the main characters are struggling to find their true place in life. Despite the fact that the characters are searching for happiness in different spheres – geographically, ideology, in the arms of lovers – it eludes almost everyone. Loftur ‘Lofty’ Harolds immigrates to Australia where he achieves financial independence and all around worldly success, yet he never visits his old home in Iceland again. Lofty is seen crying over a photo of his mother and the next day he takes his own life. Lofty’s father Haraldur spends his days and years and decades working in the community sports centre in Ísafjörður but in his mind Haraldur dwells on the sons that have moved away and on his own removal from a farm in Hornstrandir into town. Haraldur thinks of himself as a fly on the wall, observing but never participating in games at the sports centre where everyone comes but no one resides. Jörundur Haraldsson, Lofty’s younger brother, works as a minister in Reykjavík and earns a living mostly by interring people that have moved from Ísafjörður to Reykjavík but still have strong ties to their old home town. In death though, they do rest easy, finally ceasing to worry whether they should rather be in Australia, Reykjavík or Village. Village has actually transformed into Ísafjörður in Incursions – or perhaps Ísafjörður always was Village, or at least one of the possible villages throughout Iceland. The illusion of a fictional town maintained in Rúnar’s novels until now is slowly being replaced by a reality known to the reader and this development indicates that the search for what it means to be an Icelander takes place in the real world as well as fiction. The episode titled “Hlaupandi Heimdrangar” (“Home run”) is a further indication of a search on both plains, as the narrator physically looses his way when trying to retrace the paths of his forefathers but is also confused as to where his literary heritage ends and his own thoughts begin. Some of his monologue is constructed from quotes to the extent that not a single word appears original. Is he an independent and original character or merely a mosaic of already spoken words? What about real-life Icelanders?

Ástfóstur (Embryonic Love, 1997) constitutes a departure from Rúnar’s earlier work in that it is much more imaginative and fantastical. The narrator, a figure previously positioned very close to the author, is a foetus that was never born except in the text. The foetus relates the story of its parents, both possible fathers and its would-be mother Tekla. Tekla has recently broken up with her childhood sweetheart Kristófer Kári and enrolled in a program at the church-run school in Skálholt where she and the priest Kolbeinn soon grow very close. Kolbeinn, in addition to being a man of the cloth and Tekla’s teacher, is a married father of three and it does therefore not come as a great surprise the his affair with Tekla is frowned upon by both the church and the wider community. Both Tekla and Kolbeinn are driven away from Skálholt and a distraught Tekla seeks solace in the company of her old friend Kristófer Kári. Kristófer is so happy to see her again that when Tekla some weeks later realises that she is pregnant, she can’t be sure whether the unborn child belongs to Kristófer or Kolbeinn. The following weeks and months prove immensely trying for nineteen-year-old Tekla as she enters a period of intense thought and fraught emotions, which, as the foetus relates, lead to her deciding to have an abortion. This is not a frivolous decision on Tekla’s part, but health care workers and officials she has to deal with in the process treat her with the disdain and open hostility they obviously think a loose and foolish girl deserves. Tekla however is a serious young woman who has decided to have an abortion after much earnest contemplation about ethics, the foetus’s rights as an independent individual and her own responsibilities. This is a demanding chapter for the reader as all these concerns are being related by the foetus that has been aborted, or killed, as it sometimes puts it itself. There are no easy solutions in this situation even thought the fictional foetus technically attains independent life, both in the text as narrator and in Tekla’s heart. This is not to say that the novel condemns women who choose to have abortions, or that the life of a foetus is unproblematically described as more valuable than a woman’s basic human rights. The story merely flows on, life for life, simply and sincerely, and it is left to the reader to decide whether the characters made good or bad choices. Embryonic Love is more lyrical than Rúnar’s earlier work and also more innovative in the choice of subject matter. In discussing the world of a confused young woman, Rúnar certainly doesn’t shy away from tackling difficult issues, but he manages to introduce a novel perspective and simultaneously maintain a sympathetic relationship with his protagonists.

It would be easy to say that Rúnar’s next volume of short stories, Í allri sinni nekt (Uncovered, 2000), is about men and women and the interaction of men and women, but those words seem week and pretentious compared to passion, adoration, lust and love. It does the book more justice to say that is about the passion that so often characterises interaction between the sexes. “Another story” constitutes a ‘gedankenexperiment’, or thought experiment, illustrating how a single incident can lead to very different reactions in different individuals and couples. Three mates hiking in a deserted fjord happen upon a couple making love and take the memory home to their wives and mistresses. The men are variously aroused or scandalised, and the same goes for the women, those of them who get to hear of the incident. Although the unknown couple’s outdoor lovemaking provides the focus of discussion it is not the nexus of the story, rather, the story is concerned with the widely divergent reactions of different characters. In keeping with this, the stories in Uncovered are diverse and touch on many important issues. The opening story, “Nude”, being comparatively undemanding and erotic, gives rise to the suspicion that these will be stories in which sex will unproblematically be put on a pedestal as the main factor in any love affair, but happily, this suspicion is unfounded. Taken as a whole, the stories form a serious discussion about love and sex, and the relation between love and sex. “Water on window” illustrates what happens to the heart when love is overshadowed by passion and suggests that true caring and lust must go together, otherwise something will always be missing. The choice of the short story form is judicious as it allows Rúnar to create a mosaic of voices that together demonstrate the importance of sexual attraction in relationships between men and women.

Feigðarflan (Vagabondage, 2005) reviews certain aspects of Rúnar’s previous work, amongst other, more subtle themes, taking the reader back to “Embers”, one of the more enigmatic stories in Uncovered (“Embers” has also been published in the literary journal TMM 1997: 58 (2)). The reasons for the maritime accident and dead child’s cries that the reader glimpsed in “Embers” are fully explained on the last few pages of Vagabondage. This leakage between the half-fictional, half-real Ísafjörður or Village recalls the work of William Faulkner who created a fictional world geographically and culturally very closely related to his own home county. Much like in Faulkner, Rúnar’s protagonists waltz in and out of the text, appearing in different stories as main characters or bystanders while seemingly unconnected events from different novels turn out to be one and the same. The narrator in Vagabondage is none other than Egill Grímsson, narrator and possible author of Indulgence Denied. Egill has had enough, of himself and the world in general. Over the last years he has been straining to work as an author but never received the recognition he feels he deserves. Modern capitalist society, according to the bitter and ill-used feeling Egill, has no time for art except as a commodity. Thus when novels fail to make money they are judged as all-round failures, regardless of their artistic merit. Egill decides to rid his wife, children, the whole world and not least himself of his company and drives out of the city in search of a place suitable to suicide. However, as has become almost traditional in Icelandic road-trip literature and films, Egill soon starts running into some pretty colourful characters that prevent him from instantaneously fulfilling his purpose. While the misshapen journey takes him ever westward, Egill continues to brood on death and the art that has instigated the trip. Running out of petrol, he is forced to accept help from a decidedly odd farming couple who, as it turns out, have invested in a large stock of Egill’s novels on the advice of the supposedly clairvoyant wife. Authors do tend to sell better once they are dead, and this meeting rather strengthens Egill’s intentions, perhaps especially after he is nearly raped by the team of husband and wife. Egill keeps ruminating about the illusive relationship between fiction and success. He has never been able to do what so many have suggested: merely to write novels similar to those of Arnaldur Indriðason, best-selling Icelandic crime writer. The words of another successful Icelandic novelist, Guðbergur Bergson, that an author really only needs one reader, similarly ring hollow to Egill. He feels that this is an easy statement for Guðbergur to make, in light of the fact that he has so many more readers. Egill’s search for death ends at ground zero, in the fjord where he was born and raised, and what with the experience gained from the journey and Egill’s clearing posthitis, the reader is left with some hope for the poet’s eventual rebirth.

Certain common features emerge when Rúnar’s work is considered as a whole. Intimacy and touch quite often form the subject of his novels, frequently introduced as a deliberation of sex and/or masturbation. While descriptions of sexual exploits have by some been considered gratuitous and external to the plot these are intricately linked to characterisation and important to the development of protagonists who cannot touch others and therefore resort to sexual intimacy as a way of getting close to someone, both themselves and others. Sex and masturbation thus signify a lack of human interaction rather then an intimacy such descriptions may suggest on the surface. Egill Grímsson is a good example of what Rúnar explains applies to Portnoy, the main character in Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint – “his penis is the only thing that ‘belongs to him’, utterly and without qualification. It signifies his freedom” (afterword to the Icelandic translation of Roth’s Goodbye Columbus, p. 131). Masturbation and industrious sex however do not liberate either Portnoy or Egill but the point is that in both Roth and Rúnar, sex has a deeper meaning than being a mere description of the protagonist’s orgasms. Another parallel can be drawn between the work of Rúnar and Roth in that both authors intentionally do not maintain a clear distinction between fiction and reality, narrator and author. Rúnar usually writes about reality but in his fiction the search for a distinction between fiction and reality becomes secondary compared to the importance of the fictionality of reality and the reality of fiction.

III – Critic

In an essay entitled “Andfætis og umhendis” (“Antipodal and Ambiguous”, 1993) Rúnar introduces Australian literary history in Icelandic and explains the ambivalent qualities of a national identity constantly linked to the former British Empire through the inheritance of the English language. The essay demonstrates that Rúnar possesses specialised knowledge of Australian literature and he quotes Australian theorists and authors to the extent that even Australians might find it difficult to insist on the old joke about Australia, yoghurt and culture. English certainly affords speakers easy access to the international publishing scene, but because of the increasingly universal status of English it is hardly useful in forging a unique national identity. The use of English, the old Empire’s tongue, becomes a constant reminder of origins and unequal power relations. Rúnar suggests that Icelanders might draw their own conclusions from Australian and other post-colonial writings on the subject to examine Icelandic history and the emphasis on language in both the battle for independence and literature. “At what point in time,” Rúnar proposes we ask, “did the Vikings’ Norwegian become Icelandic?” (69). Australia has long dealt with the effects of a multicultural population and as Iceland has recently experienced an influx in immigration it could similarly look to Australian internal dynamics for examples of the possibilities, and also potential problems, that multiculturalism creates for a nation.

“Sýnt í tvo heimana” (“Double Jeopardy”, 1995) opens with a discussion of the binary opposite system that forms the bases of western thought in light of Jacques Derrida’s différance. Because both words and concepts only mean in relation to each other, that is, they are dependant for their meaning on juxtaposition or relation to other signs, meaning is “never fully present but always formed in relation to the absent sign” (88). As meaning is always dependant on an absent sign, so Rúnar suggests that poets in a similar position, poets who are familiar with multiple cultures without fully belonging to any one, gain a unique understanding of meaning and being. Immigrants are among these uniquely dual or ambivalently positioned individuals. Experience gained in a different cultural environment makes it impossible to ever fully return to a country of origin because such experience constitutes a second sight, always influencing previous views of the old culture. If Icelandic discourse is any indicator, it seemingly also constitutes a near impossibility for immigrants to gain a native understanding of the new country’s culture. The opposites embodied by poets in such an ambivalent in-between position often lead to fresh insights that rejuvenate traditional (read stagnated) cultures. Rúnar argues that Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses and Amy Tan’s Joy Luck Club have both functioned in this way. Rúnar further contends that in-between authors fulfil an important role as cultural translators, often deconstructing the inflexible binaries characterising traditional ways of thinking. This theory is closely related to the poststructuralist, post-colonial writings of Homi K. Bhabha, also heavily influenced by Derrida, and Bhabha’s theorisation of ‘the third space of enunciation’. While there are as of yet no in-between authors in Iceland, Rúnar suggests that writers who have spent parts of their lives working and studying overseas, such as Stephen G. and Guðbergur Bergsson, can provide similar insights in light of their extensive experiences of different cultures. The purpose of the article is partly to point out how valuable an asset cultural translators are to a continuing advancement of ideas – much in the same way as traditional translators.

I, II, III – Trinity one and whole

I have divided this article into three short chapters and discussed Rúnar’s work as if translations, critical essays and novels could be analysed as separate entities, but this is done more to comply with the requirements of traditional essay writing than as an accurate reflection of the subject. Knowledge of literary theory and critical texts is of good use to Rúnar as a translator as becomes evident upon reading the extensive afterwords accompanying most of his translations. In turn, it is also clear from reading his own work that Rúnar has been influenced to some degree by the authors whose work he has translated: earlier I mentioned common traits in Roth and Rúnar in their treatment of the links between autobiography and fiction. Finally, the words of Icelandic author Gunnar Gunnarsson, who similarly described the links between fiction and reality in his semi-autobiographical novel Fjallkirkjan, constitute a fitting description of Rúnar’s oeuvre. Neither plain fiction nor strictly based on reality, rather, the text is an example of ‘the imagination playing with facts’.

© Agnes Vogler, 2005.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 454

Awards

2012 – The DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Ást í meinum (Damaged Love)

2010 – IBBY Honorary List: Göngin (Tunnels) by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams (translation)

2008 – IBBY Honorary List: Silfurvængur (Silverwing) by Kenneth Oppel (translation)

2006 – Reykjavík City Children´s Literature Award: For his translation of Sunwing (Sólvængur) by Kenneth Oppel

2006 – Town Artist in Garðabær for the year 2006

2006 – The Icelandic Translator‘s Award: Barndómur (Boyhood) by J.M. Coetze

Nominations

2014 – The Icelandic Translator‘s Prize: Sem ég lá fyrir dauðanum (As I Lay Dying) by William Faulkner

2003 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: for his translation of Ian McEwan‘s Friðþæging (Atonement)

1990 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Nautnastuldur (Indulgence Denied)

Ást í meinum (Damaged Love)

Read more

Feigðarflan (Vagabondage)

Read moreOf og van

Read more

Í allri sinni nekt (Uncovered)

Read moreFurðufuglar og fylgifiskar: Áströlsk kvikmyndagerð í ljósi innlendra og erlendra menningarstrauma

Read more

Ástfóstur (Embryonic Love)

Read moreHermandad femenina

Read moreSjóarinn sem er ekki til: róið á mið íslenskra sjómannasagna

Read moreSýnt í tvo heimana: þreifað á tvísýnum höfundur

Read more

Sem ég lá fyrir dauðanum (As I Lay Dying)

Read more

Vegurinn (The Road)

Read more

Göngin (The tunnel)

Read more

Hvað er þetta hvað (What is the What)

Read more

Sólvængur (Sunwing)

Read more

Barndómur (Boyhood)

Read more

Silfurvængur (Silverwing)

Read more

Friðþæging (Atonement)

Read more

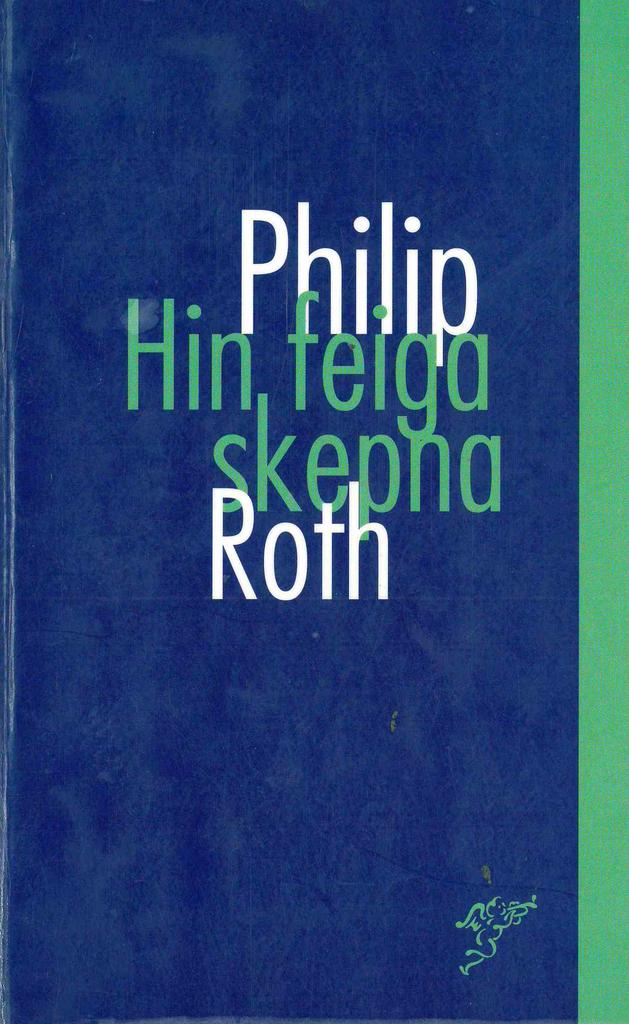

Hin feiga skepna (The Dying Animal)

Read more