Bio

Sigrún Eldjárn was born on May 3, 1954 in Reykjavík. She graduated from highschool in 1974 and in 1977 she graduated from the department of graphic design at The Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts. In 1978 Sigrún spent some time in Poland as a guest-student at the Academies of the Arts in Warsaw and Krakow. Sigrún has worked as an artist since 1978. She has exhibited her work extensively, both in solo-exhibitions and participating in exhibitions in Iceland and abroad, such as Scandinavia, Poland, Germany, USA, S-Korea, Taiwan and Japan. Art by Sigrún is owned by a number of large museums and institutions in Iceland and abroad.

Alongside her art, Sigrún has worked as a writer and has published numerous books for children. Her first book, Allt í plati (Just Joking) was published in 1980. Sigrún illustrates all her books and has furthermore illustrated a number of books for other authors, such as Guðrún Helgadóttir, Magnea frá Kleifum and her brother, Þórarinn Eldjárn. He has also written poetry for her picture books.

Sigrún and Þórarinn have received various awards for their books, and they were nominated for the Nordic Children’s Book Prize in 1998. Sigrún has also been awarded the IBBY Iceland prize Sögusteinn, the Icelandis Bookseller’s Prize and she received the Icelandic Knight’s Cross of the Order of the Falcon in 2008 for her writings for children. Apart from writing books, Sigrún has also written television manuscripts for The Icelandic National Broadcasting Service.

Sigrún Eldjárn lives in Reykjavík.

Publisher: Mál og menning.

From the Author

From Sigrún Eldjárn

For more than twenty years I have written books and done illustrations for children. Once in a while, I wonder why I do this, but most of the time I don’t think about it at all, I just keep going. I myself feel that I never really grew up, and am in fact very happy about that. I can feel the kid that jumps around inside my head, and together we have fun making these books.

Children are for the biggest part very good and grateful readers, and they deserve to get the best reading material. It is however too bad how difficult it is to make a living by writing for children. I don’t think it is easy to find a job more poorly paid.

But on we go, writing more and more, and hopefully better and better books.

Because it is so much fun.

Sigrún Eldjárn, 2002.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Sigrún Eldjárn – Adventures still unfold

In Sigrún Eldjárn’s story about Málfríður and the computer monster, Málfríður – who is a middle aged woman and very good with her hands – has made a computer. Her mother is very taken with this new thing and has much fun drawing a monster on the screen. Málfríður and the boy Kuggur then help the old mother to make the monster look even worse and finally the intention is to print it all out, to inaugurate the new printer that Málfríður has also created. Only, it so marvelously happens that something has gone awry in the design of the printer so the monster physically jumps out of it, three dimensional, life and kicking and absolutely free from being nailed down to a page.

A chase ensues, first the monster threatens the three, the mother winds up in the chandelier and Málfríður jumps up on a closet, while Kuggur crawls behind a sofa. When the monster escapes out of the house, Málfríður and Kuggur run after it in the hope of capturing it before it raises havoc among the general population. They however do not have a plan about how they mean to capture it. It comes to light that the monster loves cakes and thus they manage to lure it home – only to discover that suddenly the page has imprisoned it as was the original intention. The conclusion is this: “This is a temporary effect. What is printed out only lives for a short while and then it becomes an ordinary picture on a paper!” And Málfríður’s mother immediately sees the potential of this: now she will draw all kinds of monsters and print them out, as she is full of good ideas. Kuggur on the other hand hurries home, not to keen on meeting more monsters.

The not to brave Kuggur has appeared before in the books Kuggur og fleiri fyrirbæri (Kuggur and Other Phenomenon) (1987), Kuggur til sjávar og sveita (Kuggur on Sea and Land) (1988), Kuggur, Mosi og mæðgurnar (Kuggur, Mosi and Mother and Daughter) (1989) and Skordýraþjónusta Málfríðar (Málfríður’s Insect Service) (1995). He is rather typical for Sigrún Eldjárn’s world, where young boys are often rather reticent and not really keen on unusual adventures, contrary to the girls/women, who are delighted to throw themselves out into the unknown. The exception from this is Teitur, who is the only really adventurous male character of Sigrún’s book, while still accompanied by a girl. In this way Sigrún’s work illustrates a play with traditional gender roles, while always avoiding dogmatic propaganda. Gender studies is today a field that focuses on gender roles and equality and the Icelandic translation of the word, ‘kynjafræði’, refers to the idea of rejecting any binary oppositions between the two sexes and to open up a more flexible discourse on sex, gender and gender roles that are possibly much more varied than the traditional binary separation indicates. ‘Kynjafræði’ (kyn=sex, kynja=weird and wonderful) is an amusingly lively word in the way that an old word is taken up and used in a new way, but the prefix ‘kynja-’ not only refers to gender, but also carries the connotation of something weird and wonderful, ‘kynja’-something, animals or otherworldly creatures. As such it is also highly appropriate to describe Sigrún’s work, populated by all kinds of weird and wonderful creatures and thus it can be imagined that it is Sigrún herself who, like Málfríður’s mother, draws and creates weird and wonderful animals and creatures by the dozens, printing them out from her computer, and just like the mother does not suffer from lack of ideas, Sigrún’s imagination is apparently very lifely.

Science fiction and fantasy do not have a strong tradition in Icelandic literature, even though some works of this kind have appeared now and then. However, in the last two decades fantasy has emerged in various forms in the works of writers like Vigdís Grímsdóttir, Kristín Ómarsdóttir and Andri Snær Magnason, who has used the form in his book for children and works for adults. Andri Snær uses fantasy mainly as a tool for propaganda, and indeed it has been one of the roles of the genre from its beginning to function as a kind of a response to that period’s society and zeitgeist. Even though Sigrún’s work often refer to their contemporary society in some way, she always manages, as already claimed, to avoid all simple polemic or agitation. Instead she allows her imagination to run free and the fantasy becomes uninhibited and life.

This is amusingly apparent from her first two books, Allt í plati (Just Joking) (1980) and Eins og í sögu (Once Upon a Time) (1981), describing the adventures of Eyvindur and Halla. These adventures happen underground, that is in the sewers of Reykjavík, inhabited by the weird and wonderful creatures Crocophants, being a kind of a mixture between crocodiles and elephants. Here Sigrún refers to many things at once. The names Eyvindur and Halla belong to Icelandic history and world of folktales (as famous outlaws), while the urban legends on crocodiles in the sewers are an example of a legend that his highly American. These urban legends describe how the baby crocodiles are small and cute and make popular pets. However, they grow at an alarming rate and then it is quite popular to flush them down the toilet. After that, they thrive and grow in the sewers until they are transformed into horrible monsters that harass the citizens. (Actually I met with a small crocodile in a cage in the Central Park Zoo in New York, and he had been found walking around, apparently having experienced the fate of the urban legend, apart from being unlikely to harass anybody due to his genes who demand that he be a kind of a dwarf-crocodile, a bit like the Icelandic horse compared to the Arabian.)

On their travels around the nether worlds of Reykjavík the children meet with an ancient woman who used to know Gunnar and Njáll (from medieval Njál’s Saga) and sustains her eternal life with an eternity-stone which she keeps in her armpit. When the children have trouble with the long bearded and nasty churchwarden of Hallgrímskirkja and his friend the dragon, they similarly use invisibility stones to escape. In this way Sigrún threads the Sagas and Icelandic folktales into her work, but it may also be added that both phenomenon, the stone who gives his owner eternal life and the invisibility device are classic elements of fantasy, most recently appearing in the Harry Potter books.

These books also contain more play with form than usually seen in Sigrún’s work. A student of mine in a course on comics in the Iceland Academy of the Arts wrote a highly interesting paper where she points out that these books of Sigrún partly use the form of the comic book. Thus both books start when the children’s thoughts, appearing in thought balloons in the manner of comics, come to life. In the same way a part of the text is only in these thought and speech balloons, interacting with the text of the narrative, appearing in a more traditional manner outside the pictures.

Pictures are of course a large part of Sigrún’s work, as she is an artist as well as a writer. She illustrates her own books and here there is a reason to use the word illuminations, as it has been used to stress the role of pictures in books, often no less important than that of the text. Sigrún’s pictures span the scale, from being rather traditional illustrations as in stories like those of Teitur and the secret society called Skeleton, to being a key-element in the experience of the book. The latter can be seen in the stories of Halla and Eyvindur, Kuggur and Mother and Daughter, Hrói and Harpa, in addition to books Sigrún and her brother, Þórarinn Eldjárn, work on together. In these books Þórarinn writes poems to Sigrún’s pictures (“ljóðskreytir” or “poemstrates”). They are Gleymmérei (Forget-me-not) (1981), Stafrófskver (Alphabet) (1993) and Talnakver (Numbers) (1994). These books are driven by the pictures like the role of Þórarinn indicates.

The stories of Teitur and the Skeleton are clearly meant for older children, they are longer and there is much more text. The stories about the Skeleton (Beinagrindin (The Skeleton) 1993, Syngjandi Beinagrind (Singing Skeleton) 1994 and Beinagrind með gúmmíhanska (Skeleton with Rubber Gloves) 1996) are akin to British books for children describing children and youths who form a secret society and are intent on playing detective games. The structure of the group is highly unusual, counting two 9-10 year olds, Birna and Ásgeir, one teenagers who is a punk, Kolbeinn called Beini, and his little sister Gusa, who is only five years old in the first book. As it should be in these kind of stories the kids often find themselves in a position where they can reveal various crimes. In the second book the kids wind up staging a rock opera inspired by the events of the story, mixed with a story about a mad scientist, as Birna demands that such a person be a part of the play (she has a rather absent minded scientist for a father).

A mad scientist is then an important person in the books about Teitur. The first book, Teitur tímaflakkari (Teitur the Time Traveler) (1998), tells the story of how Teitur lives alone with his mother because his father disappeared two years earlier. It comes to light that he has been sent on a time travel by the mad scientist Tímóteus, who is a very evil man and preoccupied with gaining power over time and thus achieve world domination. Tímóteus captures Teitur and sends him into the future to spy. But Tímóteus becomes absent minded in all this excitement and forgets to explain to Teitur how he is supposed to return. Fortunately the turtle Gloría has accidentally gone into the time machine and saves the day. She is a highly unusual animal as are all the other scientist’s animals, for he uses them for his experiments. In this time journey Teitur meets with the future girl Stella, and Narfi, the boy from the past, and those three meet again in the next two books, Teitur í heimi gulu dýranna (Teitur in the World of the Yellow Animals) (1999) and Geimeðlueggin (The Space Lizard Eggs) (2001).

In addition to the stories about Teitur, the stories about B-Two (Bétveir-Bétveir (B-Two-B-Two) 1986 and Axlabönd og bláberjasaft (Braces and Blueberry Juice)1990) as well as Stjörnustrákurinn (The Boy from the Star) (1991) are also science fiction books. Those describe visits by aliens and their relations with earth children.

Geimeðlueggin is however not just science fiction, it is also akin to horror fiction a la science fiction horror films like Alien (1979). The story describes how Teitur, Stella and Narfi all find, each in their own period, mysterious red eggs. Teitur’s egg hatches and the progeny turns out to be a vindictive space lizard. Like Tímóteus before, the lizard aims at world domination, its main source of food is human flesh and the earth is its favoured place to inhabit, as the human kind does not deserve this place having mistreated its natural wealth. As already said this space lizard is quite similar to the alien in the Alien-films. That species also aimed at world domination, and had the habit of leaving its eggs around, hoping that they would hatch with the help of men who were used as hosts.

The space lizards are quite original in Sigrún’s design; they are assorted and the limbs are not necessarily attached to the body. In a really terrifying scene they seize Narfi’s sister and eat her; when the children arrive they are cleaning their teeth! But the story is not over and offers at least two kind of unexpected ends, very much in the spirit of horror fiction.

The horror story is also nearby in the stories about Harpa and Hrói. They always appear to be walking aimlessly in a mysterious wood that scares Hrói very much, but he is not at all brave contrary to the very-special Harpa. The first book, Kynlegur kvistur á grænni grein (A Weird Knurl on a Green Branch) (1997), tells how they are walking in the woods and meet with the books title character, who is searching for his sister Scrambled-Branches. She is very mischievous and has probably been caught by the Slimy Tree that is a particularly vindictive plant, probably traceable back to horror plants like the one in the Little Shop of Horrors. Harpa and Hrói manage to rescue Scrambled-Branches, even though Hrói is shaking with fear.

In the next book, Drekastappan (A Stew of Dragons) (2000), the kids go on a journey in search of a way to please Hrói’s grandfather and in the third story, Draugasúpan (The Ghost Soup) (2002), they are still travelling in the wood, this time on their way to Harpa’s aunt with a cake and some wine... Most will have realised that here Sigrún is still playing with intertextuality and connections between texts, this time using the theme about Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf. The kids do meet a wolf, much to Hrói’s consternation, but Harpa gives it a warm welcome. She finds a pot and decides to use it to make a ghost soup and starts to pick herbs and worms into the pot to flavour the soup (Harpa is a very original cook and is always finding new recipes like the ‘stew of dragons’ indicates). On their way they meet, in addition to the wolf, a skeleton, an angel and a ghost – who escapes being made into a soup though, for aunt Hrollfríður announces that the herbs are quite enough for a soup. There are also other partners on this journey who are never mentioned, for it is in these books that Sigrún’s pictures are most lively and independent from the story. A banana with legs, a small horned imp, a bat, worms, ghosts and snakes are continually circling the kids, and in the earlier books there is a similar collection of strange small creatures following Harpa around. In some cases these animals play an independent part, like the ghost in Draugasúpan and the dragon in Drekastappan, who has followed Harpa, apparently unaware of what will become of him. Even though he has never been mentioned in the text he involves himself in the story at the end, knocking on the door claiming to be lonely. And like the ghost he escapes being eaten.

The spirit of adventure that surrounds Harpa is also related to her skin colour, as she is of colour, and this underlines the play with time and setting that characterises this series, the least Icelandic of Sigrún’s books. In another story, Sól skín á krakka (Sun Shines on Kids) (1992), it is described how two children live for a while in Africa with their parents who are there with the Red Cross. In this way Sigrún is clearly attempting to work against prejudice and trying to create a multicultural setting, mirroring the relations of Áki and Ísafold with the aliens B-Two and The Boy from the Star. In the same way she has people of different ages play together. As already said Kuggur plays with the elderly mother and daughter, the secret society Skeleton spans disparate age-groups and the stories about Great-grandfather describe the relations between little Anna and her great-grandfather who is blind, but is both a prankster and a specialist in making mud cakes (Langafi drullumallar (Great-grandfather Makes Mud Cakes) 1983 and Langafi prakkari (Great-grandfather the Prankster) 1984).

In this way Sigrún creates a world in her books where anything can happen, and where adventures still unfold.

© Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, 2003.

Articles

General discussion

Sonja Hulth: “Tre islandske tecknare”

Opsis kalopsis 2000, vol. 1, pp. 23-9.

Awards

2020 - Honorable mention at Sögur, children's awards festival (with Þórarinn Eldjárn)

2018 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Silfurlykillinn

2011 – The Icelandic Optimism Prize

2008 – The Knight´s Cross of the Order of the Falcon: For her contribution to culture for children in Iceland

2007 – Dimmalimm: The Icelandic Illustration Award: Gælur, þvælur og fælur

2007 – Sögusteinn, IBBY Iceland and Glitnir Bank´s Children´s Literature Prize: For her writings for children

2006 – Vorvindar, IBBY Iceland: For her writing and illustration

2004 – The Icelandic Bookseller´s Prize: Frosnu tærnar (as the best children´s book of the year)

1999 – International IBBY Honor´s List: Málfríður og tölvuskrímslið

1999 – VISA Iceland Culture Award: For her art and contribution to culture for children

1998 – The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Halastjarna (together with her brother, Þórarinn Eldjárn)

1996 – Icelandic Broadcasting Service (RÚV) Writer´s Fund

1994 – Heiðurslaun Brunabótafélags Íslands

1992 – The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Óðfluga (together with her brother, Þórarinn Eldjárn)

1989 – Verðlaun fyrir útilistaverk í Laugardal

1988 – IBBY Iceland Award

1987 – The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Bétveir, bétveir

Nominations

2024 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Sigrún í safninu

2024 - Fjöruverðlaunin, The Women’s Literature Prize: Sigrún í safninu

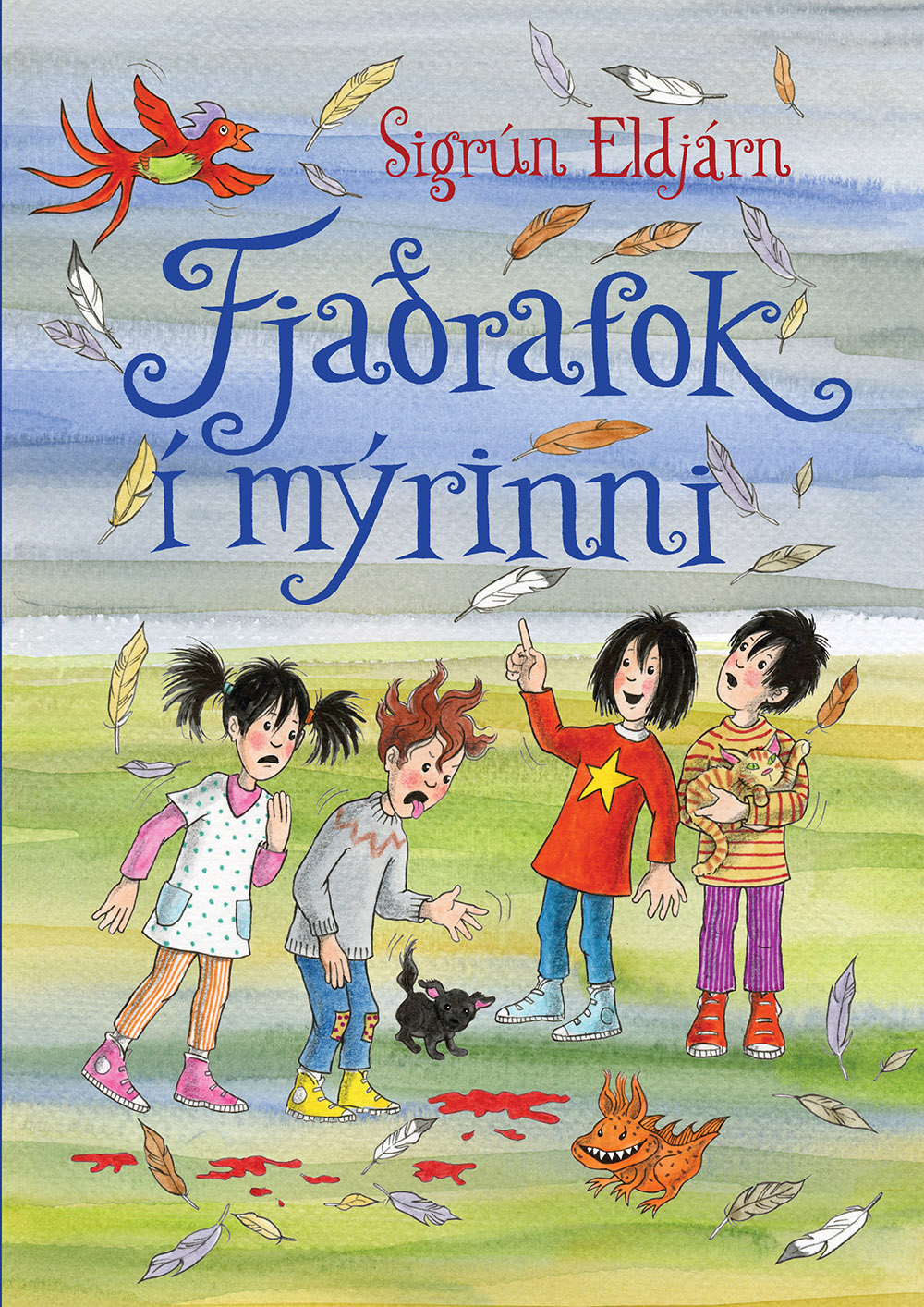

2024 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Fjaðrafok í mýrinni

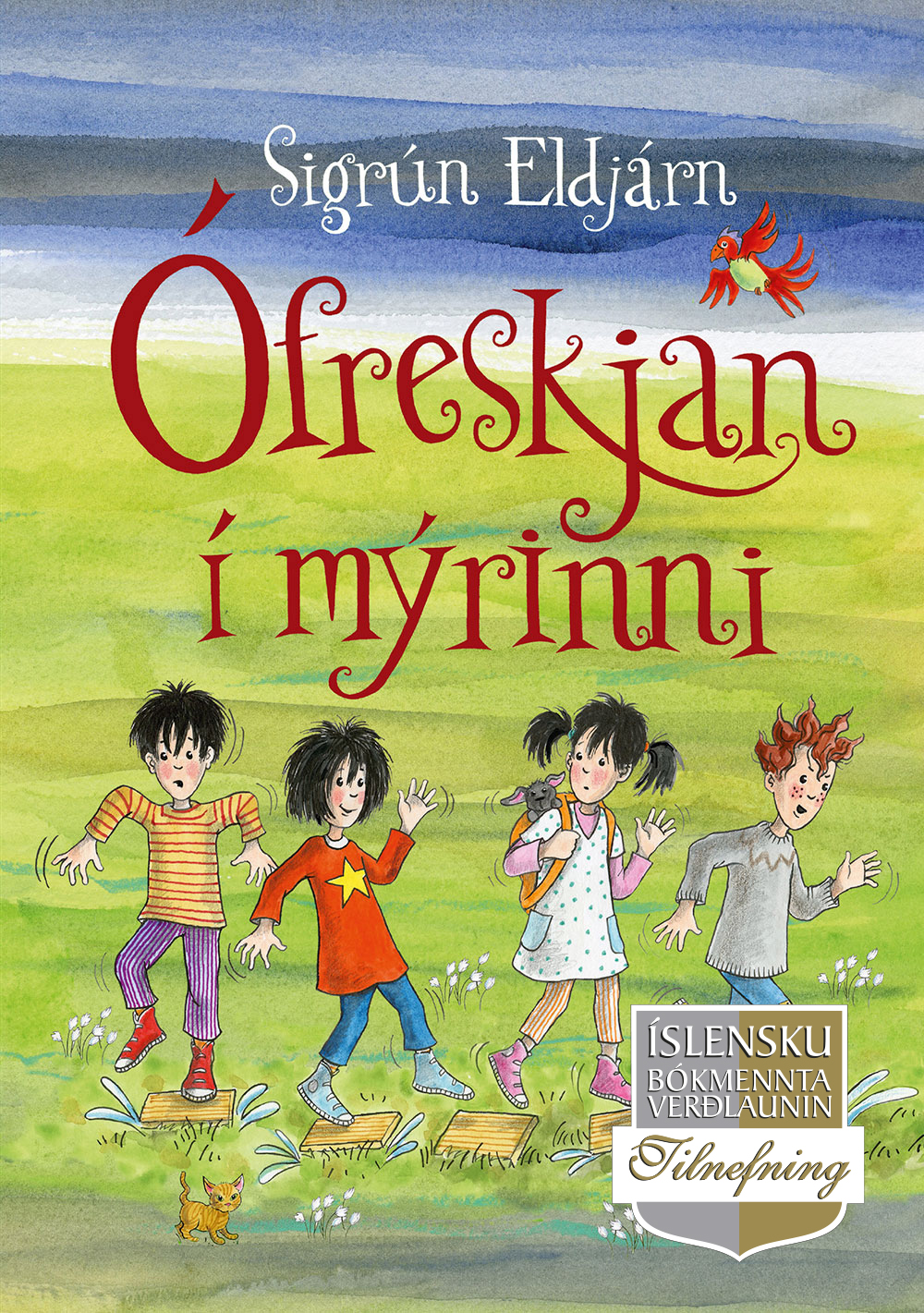

2023 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards, frumsamdar barnabækur: Ófreskjan í mýrinni

2022 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Ófreskjan í mýrinni

2021 - The Icelandic Translators‘ Prize: Öll með tölu eftir norska höfundinn Kristin Roskifte

2019 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Silfurlykillinn

2019 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Ljóðpundari, með ljóðum þórarins Eldjárn

2019 - The Nordic Council Children and Young People‘s Literature Prize: Silfurlykillinn

2014 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Fuglaþrugl og naflakrafl, ásamt Þórarni Eldjárn

2013 – Fjöruverðlaunin, The Women’s Literature Prize: Strokubörnin á Skuggaskeri (The Runaways on Shadows´ Reef). In the category of children´s and young adult fiction.

2013 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Strokubörnin á Skuggaskeri (The Runaways on Shadows´ Reef). In the category of children´s and young adult fiction.

2005 – West-Nordic Children´s Literature Prize: Frosnu tærnar

2003 – The Nordic Children´s Literature Prize: For her writings for children

1999 – The Nordic Children´s Literature Prize: For her illustrations

1998 – The H.C. Andersen Award: As a writer and illustrator

1998 – The Nordic Children´s Literature Prize: For illustrations

Fjársjóður í mýrinni (The Treasure in the Marsh)

Read moreFjársjóður í mýrinni er þriðja bókin í röðinni um krakkana í Mýrarsveit þau Stellu, Ella og Bellu sem búa með pabba sínum í gráa húsinu, og Móses sem býr með mæðrum sínum þremur í bláa húsinu. Börnin ganga í Mýrarskóla sem er stýrt af hinni orðheppnu Ásu Egg og í mýrinni býr ófreskja sem Móses þykir afar vænt um. Einn daginn banka uppá óprúttnir gestir á stórum bíl með ískyggileg plön um framtíð mýrarinnar í farteskinu.. .

Hlutaveikin

Read moreJólin nálgast. Freysteinn Guðgeirsson verður æ spenntari með hverjum degi sem líður. Á endanum koma þau samt og hann getur loksins, LOKSINS opnað alla jólapakkana. En þá kemur dálítið í ljós sem reynist erfitt viðureignar þó allt fari vel að lokum.

Fjaðrafok í mýrinni (The Kerfuffle in the Marsh)

Read moreÞað er eitthvað undarlegt að gerast langt úti í bullandi og sullandi mýrinni. Hvaða rauðu slettur eru þarna úti um allt? Er það tómatsósa? Jarðaberjasulta? Eða eru þetta kannski BLÓÐSLETTUR?. .

Ófreskjan í mýrinni (The Monster in the Mire)

Read moreÍ útjaðri lítils þorps standa tvö hús; annað þeirra er blámálað og umkringt þéttum trjálundi, hitt er bæði grátt og hrörlegt. Handan við húsin er mýrin, víðáttumikil og hættuleg. Einhverjir eru líka að pukrast í mýrinni. Líklega vita þau ekki að þar býr ófreskja!

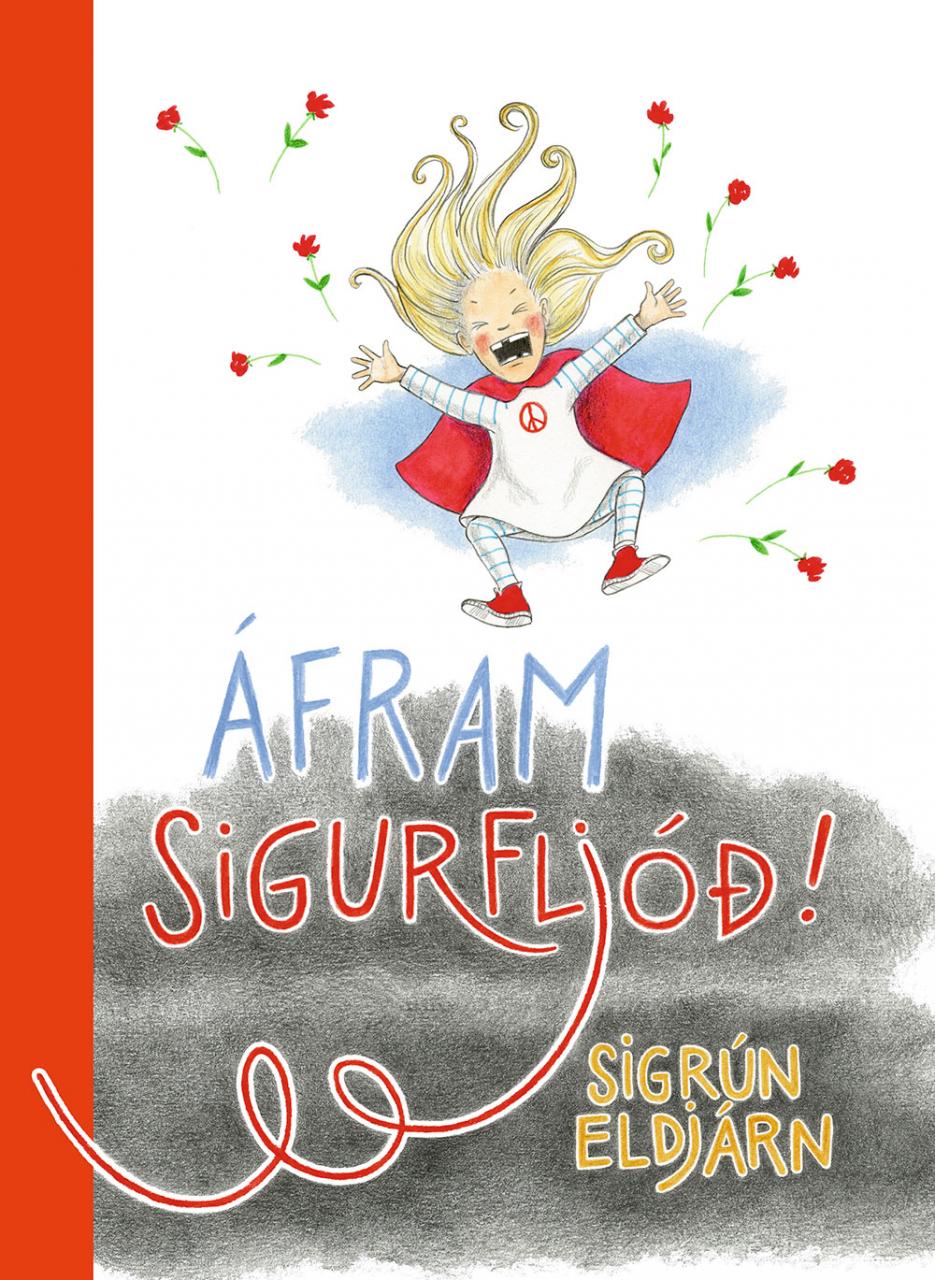

Áfram Sigurfljóð! (Go Sigurfljóð!)

Read more