Bio

Sölvi Björn Sigurðsson was born in Selfoss on October 7 1978. He lived in Selfoss until the age of 11 and then moved to the capital area. After finishing his secondary education in Reykjavík in 1998, Sölvi studied French at Université Paul Valery in Montpellier for a year and then went on to study Icelandic and Comparative Literature at The University of Iceland, graduating with a B.A. degree in 2002. He received his M.lit. degree in Publishing Studies from The University of Sterling in Scotland in 2005. In addition to Scotland and France, Sölvi has lived in Spain and England. He has done a number of jobs through the years, sold books, sat churches, built windows, documented archeological findings and looked after national treasures.

Sölvi has been the editor of several works, the first was the literary magazine Blóðberg which he and Sigurður Ólafsson published and edited in 1998. Other editing includes the poetry collection Ljóð ungra skálda (Poems by Young Poets), where Sölvi follows in the footsteps of Magnús Ásgeirsson who edited a book with the same title in 1954. Sölvi’s first published work of fiction is the poetry book Ást og frelsi (Love and Freedom) from 2000. Since then, he has sent forward more books of poetry, quite a few translations and four novels, the most recent being Gestakomur í Sauðlauksdal (Guests in Sauðlauksdalur) from 2011. Sölvi’s two-volume work on fresh-water fishing in Iceland, Stangveiðar á Íslandi and Íslensk vatnabók (Angling in Iceland and The Book of Icelandic Waters, respectively) won the DV Cultural Prize in 2013 and was nominated for The Icelandic Literature Prize the same year.

Sölvi Björn Sigurðsson lives in Reykjavík.

Publisher: Mál og menning / Sögur.

About the Author

Quintessential Icelandic beauty and harsh, ugly reality – a view of Sölvi Björn Sigurðsson

“Can I help you?” asked the Girl on the Switchboard, who was wearing dark blue jeans and a slightly faded red t-shirt marked from the Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

“I don’t know,” I said apologetically. I was being as honest as I could: I really did not know. “To tell you the truth, I was hoping you could tell me why I’m here.”

“Don’t worry, we’re always getting people here who don’t know what they want.”

I liked this girl; she seemed to be distinctly free of being ... quintessentially Icelandic.

“So you don’t find me quintessentially Icelandic?” she asked. I was taken aback.

“Can you read my thoughts?”

“Of course. I’m the Girl on the Switchboard.”

Of course, what was I thinking.

(Fljótandi heimur [Floating World], 2006, p. 8)

Two main ‘voices’ can be identified in Sölvi Björn Sigurðsson’s writings. One is a traditional voice that continues classical motifs and is characterised by rich and decorative diction and a nostalgic tone. This traditional voice could be described as “quintessentially Icelandic,” particularly in view of the approach in the stories where it is employed. More often than not, these stories contain some reference to Iceland’s cultural heritage and past. The excerpt from Fljótandi heimur (Floating World, 2006) quoted above shows an example of the voice that emerged later in in Sölvi’s writings and the boundary between the two. The narrator distances himself from the term “quintessentially Icelandic” and gives it a negative shade. The counterweight to the quintessentially Icelandic voice is a candid and sarcastic voice that exposes human vice and weakness, highlighting how imperfect and incomprehensible our existence is. There is an angst-ridden, angry-young-man touch to this second voice and a certain lack of pity when it comes to dealing with the darker facets of existence. Sölvi is a multi-talented writer and he uses language with skill both in poetry and prose. In his writings – which span poetry books, novels, translations and academic works – he does not break with tradition; rather, he sticks to the traditional rules but presses them to the limits, jumping between the thoroughly Icelandic tradition and searing ugliness, occasionally mixing them together.

The good old stuff: Selfoss, potatoes and the old masters

Sölvi Björn’s first novel, Radíó Selfoss (Radio Selfoss, 2003), is a fairly traditional Bildungsroman. The narrator, Sigurður Óli, has just moved as a child, with his family, from Denmark to Selfoss (a small town just over 50km east of Reykjavík), where he meets his best friend, Einar Andrés. The story covers Sigurður Óli’s childhood and early life, from kindergarten until his twenties. It has a nostalgic colouring and is written in the style of a memoir. The world was simpler and clearer in the old days, and more alluring. In the eyes of a child growing up in the town of Selfoss in the 1980s and 1990s, everyday things were shrouded in mystery. In Sigurður Óli’s memoirs, radio possesses magical possibilities, the immediate surroundings in Selfoss are strange, ‘foreign countries’ means only the Scandinavian countries and music has supernatural qualities. Even though it is supposed to be describing a child’s experience of these things, the style in Radíó Selfoss has more developed stylistic features:

Once it so happened that I caught a fine Arctic char near the concrete sewage outlet pipe near the top of the Fagurgerði area. The fishing had been poor lower down where the water was fresher so we climbed out along the pipe and cast straight out into the sewage.

(Radíó Selfoss, p. 52)

From the outset, the style and vocabulary are adult, which makes an amusing mixture when combined with the narrator’s understanding of the world, which is childlike and often involves misunderstandings. For example, Sigurður Óli understands the ‘lack of inspiration’ of which is father, an angst-ridden musician, is accused, as meaning the same as ‘asthma’ and cannot understand why adults find it offensive to be called an “impy seal” (imbecile). Notwithstanding this humour, there is a great deal of sorrow under the surface of the story: parents abandon their children, people have problems with alcohol and their own sexuality – but the limitations of a child’s understanding act as a buffer against the full implications of the difficulties that plague people in Sigurður Óli’s world.

Various motifs in Radíó Selfoss make reappearances in Sölvi’s later books. One of these is his passion for angling; the detailed descriptions of Sigurður Óli’s fishing trips can be seen as a sort of adumbration of the impressive twin publications Stangveiðar á Íslandi (Angling in Iceland, 2013) and Íslensk Vatnabók (The Book of Icelandic Waters, 2013) that followed a decade later. Though these are classified as factual books it is difficult to exclude them from a discussion of this author’s creative writings. In between their quotations from Egils saga and information about angling from mythology and other literary works, they contain beautiful reflections on the sport of angling. Sölvi presents angling as a sort of meditational exercise in which the peace of the natural environment and the clarity of the water raise the individual to a new level of existence. Angling could be called one of Sölvi’s quintessentially Icelandic subjects in view of the connections between it and Icelanders’ shared history and culture, as he explains it in these texts.

In his fourth novel, Gestakomur í Sauðlauksdal** (Visitations in Sauðlauksdalur, 2011), Sölvi throws new light on Iceland’s distant past. The narrator and main character is an historical figure, Björn Halldórsson, vicar of Sauðlauksdalur in the eighteenth century, who was one of the main leaders of the Enlightenment in Iceland and did much to modernize Icelandic society at the time. His achievements in the cultivation of potatoes forms the basis of this book; the main focus is on an elaborate feast that he intends to hold for the people of his parish to introduce them to a wider range of culinary possibilities in the hope of giving his fellow-countrymen, who had often experienced famine, a means of food security. This may sound like an uninspiring subject for a novel, and certainly Sölvi is here investigating a corner of history that many Icelanders have no interest in knowing much about. Instead of giving us a chance to bask in the glory that arose in the boom years and is now being kept alive by a glut of tourists following the economic collapse, Sölvi turns here to Iceland’s lean years and the inglorious realities of ideals and less dramatic revolutions :

My kingly potato is not only the rich royalis but also the black potato with flesh both brownish and pale like the rainbow itself plunged into dusk. There, I am told, can be seen cornshafts in shadows at sunset and dawn, the waves of colour in the deep golden meadow; from there I draw the juices of the soil and in all its gradations I sense the plenty of the earth that was created for bounty and nurture; this is the potato of life, Iceland’s tomorrow, the rout and ruin of all starvation and shortage.

(Gestakomur í Sauðlauksdal, p. 39)

The quintessentially Icelandic voice rules the roost in Gestkomur where Sölvi emphasises the importance of Björn’s work in the service of the Icelandic people and shows what he can do with the language. The narrator’s struggle against destitution in Iceland can be heard in every sentence, as can Björn’s conviction of his own excellence.

The sentences are powerfully worded, sprinkled with Latin in the manner of men of learning of the time and given extra dignity by ceremonial and emotionally-charged imagery. This is not only the ideal style for looking into the life of an Icelander of the eighteenth century; it also achieves new heights in long and appetizing descriptions of food. The reader’s mouth waters at the overwhelming enumerations of all the culinary delights that Björn and his household create and perfect for the great feast.

Sölvi’s poetry is varied and complex and defies classification under one or the other of these voices; he has already produced a large variety. He has tackled the more traditional and formal styles and is thoroughly familiar with the classics, having translated poems by Shakespeare, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Byron and Keats. He began translating early in his career and published translations along with original poems in his Vökunætur glatunshundsins (The Ferret’s Waking Nights, 2002) and 50 ½ sonnetta (50 ½ Sonnett, 2015); in 2000 he published a book consisting entirely of translations of sonnets by Keats. His poetry books vary widely both in style and approach. The first, Ást og frelsi (Love and Freedom, 2000), contains fairly traditional poetry cast in established forms including the Icelandic ferskeytla quatrains with end-rhyme but also some freer forms. As the title indicates, love is a dominant theme, but not always in the positive guise one might expect. In many of the poems, the choice seems to be between love and freedom, with love depicted as the harsh force at work in brokenheartedness. Even with this slightly dark colouring, however, Ást og frelsi comes nowhere near Sláturtíðin (Days of Slaughter, 2012) for gloom. Sláturtíðin is more experimental than Sölvi’s earlier poetry and the style is more pared down and merciless. No longer are the poems bitter-sweet; here they are excoriating and painful, cutting in to the core, the quick of life, by way of the flesh:

here we come rushing

weathered chunks of meat

for the irresistible offer

with long-ingrained toughness against darkness & depression

that raises body after body up from the singeing morningshere we live rhythmically in the spinning-wheel of moon and beach

spun towards the stars in the wool jerseys of the lights

corpse-cold we stretch out for the scythe & suet that produces

another new day & wakes us dead into the brightness

(Sláturtíðin, p. 7)

In 2015 Sölvi published two books of poetry which again took new departures. Kristalsaugað (The Crystal Eye) is a sort of folktale: all the poems in the book make a narrative in which imagery from the natural world plays a major role. The same year saw the appearance of 50 ½ sonnetta, which contains some varied sonnets that Sölvi wrote in connection with Reykjavík’s annual ‘Culture Night’ festival in 2014, together with translations. The sonnets include an ode to a bathing costume, cats that cook pancakes, friends and relations of the poet, angling and parliamentary elections. Sölvi gives an account of the background of each sonnet in the introduction and also examines the changes that have taken place in his poetry. At first he was more concerned with form and whether his poems met the requirements of each metre, but more recently he has relaxed these formal requirements:

It is also a question whether there is any real need to follow the form very closely simply because it is being used as a basis. At the end of the day, a sonnet is no good if it fails to amuse the reader, or at least arouse in him a feeling more pleasant than that of finding one has woken up too late to catch a flight. (50 ½ sonnetta, p. 5)

Sölvi’s poetry has got going and he employs the rules of the tradition but no longer allows them to hold him back. But Sölvi’s poetic achievements go further. In 2005 he published a unique work in which the two voices in his writing are combined to a great extent.

Blunt social satire: Dante in the disco, Murakami and the death of loved ones

Gleðileikurinn djöfullegi (The Devilish Comedy, 2005) is a two-hundred-page narrative poem in terza rima like Dante’s Divina commedia. The quintessentially Icelandic and the direct, sarcastic voice are combined here: the form is a clear reference to tradition, not only to Dante but also to the use of the rhyme-scheme by Jónas Hallgrímsson, while the discontinuity between the phraseology used by the main character and the others that he meets distances Sölvi’s tale from the sublime subject-matter of the works of Dante and Jónas Hallgrímsson. Sölvi relates a pub-crawl through the streets of Reykjavík by a young poet, Mussju, accompanied by no less a figure than Dante on his journey through the inferno of the night; equivalent to the levels of hell in Dante’s Inferno are various bars located closer and closer to the centre of Reykjavík and the night-life to be found within them. In this way, Sölvi manages to bring contemporary literature into line with the classical tradition, resulting in a very special and ambitious piece of writing. There is an element of ironic social satire in that, underneath the sublimity suggested by the style, Mussju’s pretentiousness and implied mental superiority are ridiculed by those that he meets. His lofty utterances are out of step with the phraseology of the ordinary souls he encounters in his journey through the inferno of Reykjavík:

Along they’re borne amid the thronging muddle

-transient is the world and every glass of ale:

a share has hit the floor, forming a puddle.

“Who are you?,” says he. “Is it from here you hail?”

(By who’s-who-lore your Icelander’s obsessed.)

“What? You ask have I got Mary Jane for sale?

Great opening line; I see you’re self-possessed ...”

(Gleðileikurinn djöfullegi, 82)

The gap between Mussju and his surroundings is highlighted again and again throughout the poem, and Mussju seems to be the only one to see the grief and mental torment that characterise “night-life” in Iceland. The pessimistic tone in Gleðileikurinn djöfullegi has much in common with that of two of the author’s novels: Fljótandi heimur (2006) and Síðustu dagar móður minnar (The Last Days of My Mother, 2009); on the other hand the novels are very unlike the poem in that their vocabulary is much more pared-down and direct.

Many things make Fljótandi heimur unique in Icelandic literature, not least the way Sölvi draws deliberately on the style of a well-known foreign writer and his motifs. Haruki Murakami is a Japanese writer who has gained international popularity, is seen as having carved a niche of his own in the literary world and has long been named as a potential recipient of the Nobel Prize. Murakami’s books often feature as their principal characters taciturn males who stand aloof from traditional society, not because they have any special talents or outlook on life, but simply because of a lack of interest in their surroundings and a lack of personality. These colourless main characters are often drawn into surreal circumstances by mysterious females; this is exactly what happens to Tómas, the main character in Fljótandi heimur. Tómas moves to Reykjavík from the country and starts university. Like Murakami’s characters, he is the plaything of fate; he seems not to take many decisions on his own account and instead floats along on the currents of the world. This can be seen, for example, in his friendship with the unpleasant Hallgrímur: Tómas seems to be the only person who can put up with him and not let his grotesque opinions trouble him. Tómas accepts his environment as it is without trying to make it conform to his own wishes. At the beginning of the work this attitude of Tómas’s comes out in his reaction to a telephone call from a mysterious woman. The woman asks him personal questions and knows an unnatural amount about him and his life. This is an obvious reference to Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1997). Tómas is annoyed at first, but later comes to accept the woman’s strange phone calls and ends up regarding them simply as part of life.

Tómas meets the half-Japanese Saiko at the beginning of the story and is immediately captivated by her. Saiko is a panty-hose model whose memory is full of gaps after some brain tests she took part in at a mysterious company in Reykjavík. She has an immense impact on Tómas’s life: she introduces him to Murakami’s writings, for example. Sölvi makes no attempt to conceal the references to Murakami’s writings; on the contrary, he emphasises the presence of that writer in the work by mentioning many of his books and also employs some obviously Murakamian motifs. Fljótandi heimur pulls no punches and deals with serious and sensitive issues in a clear and relatively clinical way. The style is purged of emotional overtones, which gives the story a chilly character, yet at the same time a certain honesty. The problems in Fljótandi heimur are placed on the table and lit up by a sterile fluorescent light: everything is exposed. A similar approach can be found in Sölvi’s more recent writings, in which he examines grief and human fallibility.

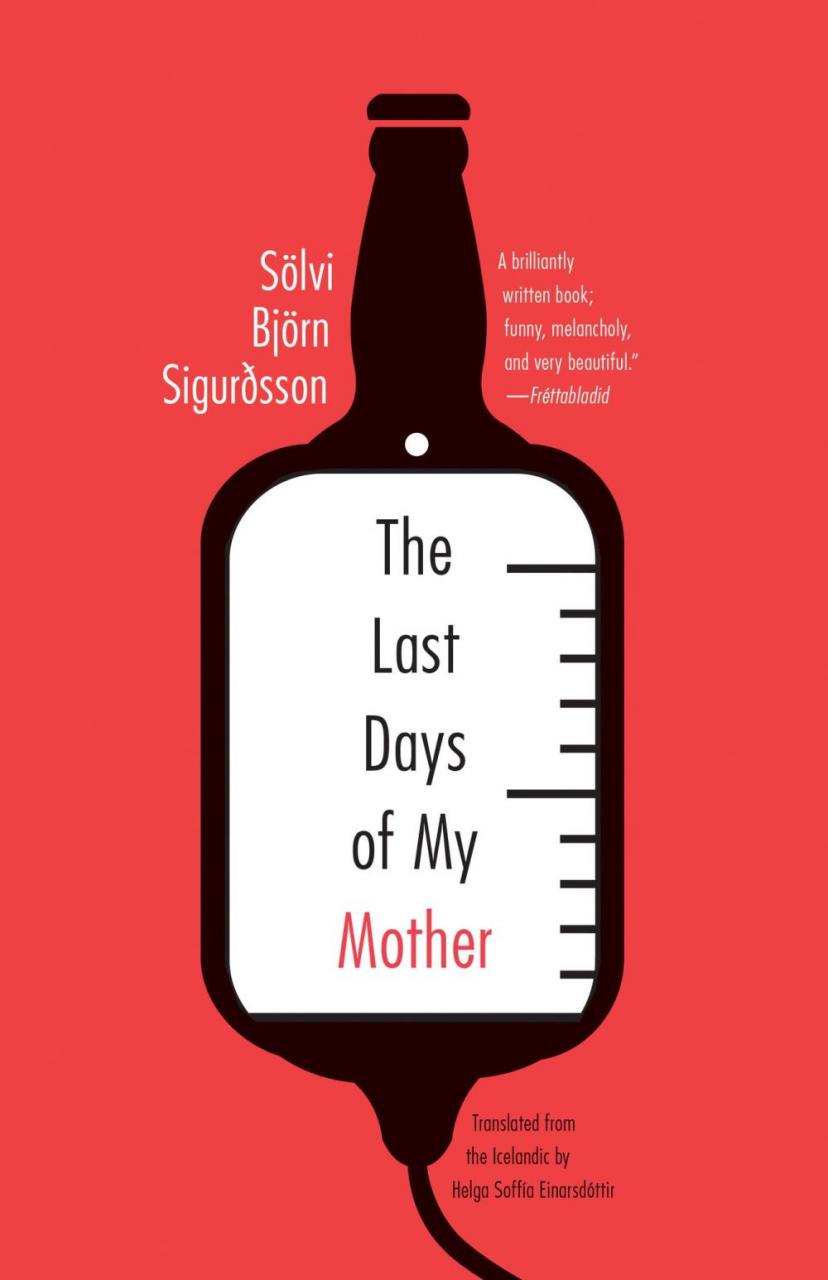

Síðustu dagar móður minnar (2009) is the story of Hermann “Trooper” Willyson and his mother Eva. After suddenly breaking off a long-term relationship, Trooper moves in with his mother again, and only four months later she is diagnosed with cancer. After some months of inactivity and self-pity, Trooper pulls himself together and decides to do everything he can to make his mother’s life better. “From now on, every single day would be a work of art in which the brush-strokes would be based solely on the aim of making Mum happy during these last days of her life.” (Síðustu dagar, p. 12). Trooper persuades Eva to go for treatment in Libertas, a clinic and palliative care centre near Amsterdam that uses unconventional approaches in treating cancer. Mother and son therefore move to Holland and the story covers a period of some months in 2008 in Amsterdam and the care centre.

Trooper’s relationship with Eva is rather different from traditional mother-son relationships, but they are a long way from being traditional people. At first, their time in Amsterdam consists of non-stop drinking, spiced with a bit of soft drug-taking. They persuade themselves that they are celebrating life and enjoying it while the miracle drug from Libertas gets to work on eliminating Eva’s cancer, but it is difficult, both for the reader and for these characters to avoid the feeling that behind all this indulgence lies the desire to escape from their circumstances. Deep down, they know that Eva is seriously ill and will probably not survive her illness, and that they went to Libertas not only for the treatment but also because of its policy of assisted euthanasia.

Síðustu dagar móður minnar is a beautiful story about the searing power of grief. We human beings are deeply flawed and scarcely know how to tackle our lives. In this swirling interplay of coincidences and contradictory emotions, one might think that death was a welcome anchor in an otherwise topsy-turvy existence, but we do not meet our fate with dignity. We are terrified and flee from the truth; we deny grief and cling desperately to an artificial happiness that is built on sand. Sölvi’s novel brings a new angle on the death-struggle of the individual by resisting the temptation to make it less disturbing. The style is harsh and direct , as in Fljótandi heimur, and it illuminates human existence in an unattractive – but at the same time honest – manner. Trooper’s descriptions of his own appearance, behaviour and his drinking bouts with his mother are merciless, and the denial of both mother and son of what awaits them shines clearly through them. This makes it harder for the reader to allow himself to forget what is coming and to slip into Trooper and his mother’s way of thinking in their fruitless attempt at escaping their emotions. Sölvi’s candid and unadorned voice cuts through the grief and raises many interesting questions about euthanasia and what role we should be allowed to play in our own deaths and those of our loved ones.

Finally we come to Sölvi’s most recent novel, Blómið – saga af glæp (The Flower – a Crime Story, 2016). The reader may pick up on various connections to Sölvi’s earlier works, in particular the ones previously mentioned as his more direct writings. It tells the story of the Valkoffs, an Icelandic family still traumatised by the sudden disappearance of six year old Magga Valkoff thirty-three years ago. Following a cryptic prologue, which describes a person with a pale mark and a glowing cockroach, the story turns to Bensi, Magga’s older brother who was with her the day she disappeared. Bensi wakes up in the middle of the night and sees the lights are on in his childhood home across the street, where his mother still lives. He decides to visit his mother, who can’t sleep either as it turns out, and question her about the past and about Magga’s disappearance. The first half of the novel is framed by this conversation and touches on the fateful year of Magga’s disappearance, the peculiar life of Bensi’s father Pétur Valkoff, the summer when Bensi met his wife and other important events in their lives. The mystery of Magga’s fate becomes more complex and suspenseful as the reader is filled in on the family history. The strange story of Pétur’s life as a scientist in the Soviet Union involves glowing cockroaches and supernatural characters, and adds a touch of science fiction or horror to the novel. There are clear similarities with Fljótandi heimur as Sölvi breaks with the reader’s sense of reality in a fundamental way. In Blómið, however, he forgoes any stylistic buffer such as the Murakami pastiche in Fljótandi heimur, and approaches the supernatural in a more personal manner.

Blómið also harkens back to Síðustu dagar móður minnar with its emphasis on the relationship between parents and children, marred by trauma. It’s a tragic story of the loss of a child, a loss which destroys a marriage, a childhood and the link between a son and his parents. The novel also asks questions about the nature of love and grief. Is grief unescapably stronger than love? Or is grief overcome only by love? It will be interesting to see whether Sölvi continues to shape his unique approach to private trauma and the fantastic in the future.

Már Másson Maack, November 2016

** The unabbreviated title is: Dálítill leiðarvísir um heldri manna eldunaraðferð og gestakomur í Sauðlauksdal : eður hvernig skal sína þjóð upp reisa úr öskustó (A short guide to methods of cooking for gentlefolk and visitations in Sauðlauksdalur, or, how to raise one’s nation from the ash-heap).

Awards

2015 – The National Broadcasting Service‘s Writers‘s Fund

2013 – DV Cultural Prize for nonfiction and scholarship: Stangveiðar á Íslandi (Pole Fishing in Iceland) and Íslensk Vatnabók (Icelandic Fish and Their Catchers)

Nominations

2017 – The Icelandic Translators‘ Award: Uppljómanir & Árstíð í helvíti (Illuminations & Une saison en enfer) by Arthur Rimbaud (with Sigurður Pálsson)

2013 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Stangveiðar á Íslandi (Angling in Iceland) and Íslensk Vatnabók (Icelandic Fish and Their Catchers). In the category of nonfiction.

2009 – The Icelandic Translators’ Award: Árstíð í helvíti (A Year in Hell), a translation of poetry by Arthur Rimbaud

2008 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Árstíð í helvíti (A Year in Hell)

Anatómía fiskanna (The Anatomy of Fishes)

Read moreÁ samkomustaðnum Glóðarauganu ríkir sundrung eftir að Guðmundur Hafsteinsson hefur að semja smáauglýsingar í mannlífsblöð um líf sitt þar og annarra er staðinn sækja. Póstþjónusta Reykjavíkur sér þess ei annan kost en að gefa út sérrit til skýringar á því hvers vegna útburðarkonan Absentína Valsdóttir kýs að dreifa ekki þeim auglýsingum.

Melankólía vaknar (Melancholia Awakens)

Read moreEmbla fer í ferðalag á heilsuhæli í afskekktum dal við nyrstu strendur Íslands. Á leið þangað taka málin óvænta stefnu. Í faðmi fjallanna á Fagraskaga sækja á Emblu spurningar sem krefja hana um að leita aftur til upphafsins. – Nútímaævintýri frá einum af okkar áhugaverðustu höfundum.

Blómið – saga um glæp (The Flower – A Crime Story)

Read more

50½ sonnetta (50½ Sonnett)

Read more

Kristalsaugað: þjóðsaga (The Crystal Eye: A Folk Tale)

Read more

The Last Days of My Mother

Read more

Stangveiðar á Íslandi (Angling in Iceland)

Read more

Strumparnir: hvar er gáfnastrumpur? (The Smurfs: where is the talent smurf?)

Read more

Dálítill leiðarvísir um heldri manna eldunaraðferð og gestakomur í Sauðlauksdal: eður hvernig skal sína þjóð upp reisa úr öskustó

Read more