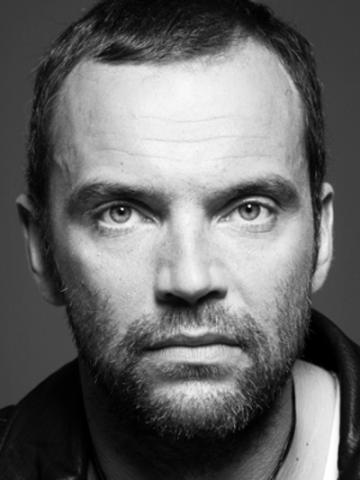

Bio

Stefán Máni was born in Reykjavík on June third, 1970. He grew up in the town of Ólafsvík in West Iceland, and lived there untill his early twenties. He completed primary school and has since gained a varied experince doing manual labour and working in the service industry. Stefán Máni has worked in the fishing industry, done construction work, carpentry, plumming and stonemasonry, gardening, he has been a night watchman, done cleaning work, bookbinding, as well as working with teenagers and in mental hospitals. Stefán Máni lives in Reykjavík.

Stefán Máni’s first novel, Dyrnar á Svörtufjöllum (The Doors to Black Mountains) was published in 1996. He has since then put forth multiple novels. In addition to this he has written some young adult novels and a childrens book. A film adaptation of his 2004 novel Svartur á leik (Black’s Play) was released in 2012, directed by Óskar Thor Axelsson.

Stefán Máni is a four-time recepient of the Icelandic Crime Writer’s Award, Blóðdropinn, most recently in 2025 for the novel Dauðinn einn var vitni (Death Alone was a Witness). In 2008 the novel Skipið (The Ship) was nominated for The Glass Key, the Scandinavian Crime Writer’s Award, and the novel Svartur á leik was nominated for the same award in 2006. Some of his books have been translated to many languages.

From the Author

To write or not to write: Back to the past 1 & 2

(F REW … 2002101999876, STOP. PLAY)

/: BREAK ON THROUGH (TO THE OTHER SIDE)

In the fall of 1996, I decided to change jobs, quit at a big shrimp processing factory (that later went under) and took a job at a new fish factory where I packed frozen filets of fish, but the mind wasn’t at this new job, even if the body toiled there from 6 in the mornings until 8 in the evenings, I had in fact made up a little novel in my spare time, a story I was extremely fond of, and still am, I walked to and fro in my rubber boots and thought about the book, about a possible publication, about writing, while the cold and swollen hands sorted fish filets by type and weight, and finally mind had the better of flesh and the thirst for adventure better of sense, I hesitantly resigned, stuffed all my belongings into an old Lada and drove to Reykjavík with a knot in my stomach, a light in my head and the script of Dyrnar á Svörtufjöllum (The Door to Black Mountains) in a brown envelope in the passenger seat …

(F REW … 199654321, STOP. PLAY.)

/: LIGHT MY FIRE

When Hraðfrystihús Ólafsvíkur (The Fishing Factory in Ólafsvík) went under in 1991, a void was formed in this small fishing village, I lost my job, together with a big part of the other villagers, and inside me a void was also formed, a big black hole full of doubts about the future and pressing questions about purpose and faith, a hole that it would have been easy to fall into and be lost in forever, but after having been at its edge for one, two years and staring lost and without much hope down into the dizzying darkness, I one day sat down with a pen and paper in hand and managed with effort, patience and countless trials and errors to close this soulless well with words nailed together on paper: I had written a poem, which I called “leikhús” (theatre):

í ilmandi þögninni

sem lifir eftir

endurtek

ég sporin

endurtek

ég orðin

endurtek

ég leikinn

frá upphafi

til enda

í tómu húsinu

og hneigi mig síðan

og felli tár

á myrkvuðu sviðinu

um ókomin ár

því þótt tjaldið sé fallið

blómin skrælnuð

og fólkið

fyrir löngu farið

er sýningin

rétt að hefjast.

[in the fragrant silence

that survives

I repeat

the steps

I repeat

the words

I repeat

the game

from start

to finish

in the empty house

I then bow

and shed a tear

on the dark stage

in years to come

for though the curtain has been closed

the flowers have withered

and the people

are long since gone

the show

is just beginning.]

Stefán Máni, 2002.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Below are two articles about Stefán Máni's work. To read the newer one, click here.

Darkness calls

After Israel: Story of A Man (Ísrael : Saga af manni 2002), a novel about the migrant worker, Stefán Máni started writing a different kind of novel, moving into the world of crime. His next novel was Black‘s Game (Svartur á leik 2004), a crime novel focusing on the Reykjavík underworld. Since then nearly all of his works have belonged to the crime genre, often with undertones of mystery and horror with references to the underworld of drugs and violence. The exception to this is Tourist (Túristi 2005), an experimental fusion about writers and fiction. As all of Stefán Máni‘s work the novel is very dark, with many references to horror fiction.

In the midst of this darkness, Stefán Máni can also show a lighter streak, as in the children‘s book he co-authored with Bergrún Íris Sævarsdóttir Hin æruverðuga og ættgöfuga hefðarprinsessa fröken Lovísa Perlufesti Blómasdóttir: daprasta litla stúlka í öllum heiminum or The Honorable and Noble Princess, miss Lovísa String-of-pearls Bloom’s- daughter (2016). This is a story about a little princess who lives all alone in a tower.

Uncanny underworlds

There are no fairy tales in Black‘s Game. The main character is Stefán Kormákur Jónsson who works at a bar in Reykjavík where he is introduced to the underworld of the city. The bar‘s owner, Jói Faraó, and the manager Tóti, who is also the bouncer, fight over the drug market in town. Before long Stefán (who is called Stebbi psycho by Tóti), finds himself involved in a power struggle between generations: Jói Faraó is an old type of a drug lord while Tóti and his gang represent a new generation. Stebbi becomes a part of Tóti‘s gang and their progress in the world of crime is detailed. The mysterious Bruno is also an important character, both for the underworld and for Stebbi. As should be clear the subject matter is the underworld life of drugs, crime and violence.

This might seem a classic plot: the story of an innocent young man who sets out on a life changing journey. However, Stefán Máni does not offer a simple formula, as seen in a revealing final part. The style is tough and free of pretension and the novel enjoyed considerable popularity, especially among young males who tend to often to feel lost in the Icelandic literary landscape.

Eight years later Black‘s Game was adapted into a film. The cool toughness and the violence is given its full due while the more delicate mysterious undertones that make Stefán Máni‘s stories so interesting are absent. The film was a hit and since then Stefán‘s other novels have been optioned for adaptation.

When Black‘s Game was published the Icelandic crime novel was facing some heat, having just become popular following upon two successful novels by Arnaldur Indriðason, Jar City (2000) and Silence of the Grave (2001). Authors like Árni Þórarinsson, Stella Blómkvist and Viktor Arnar Ingólfsson had become popular, much to the consternation of other writers who thought that this popular wave was garnering too much attention in the media. Possibly this was the reason Stefán Máni reverted back to ‘Literature‘ in his next novel. Tourist is about writers and literature, and writing in general, complete with poorly disguised references to the world of Icelandic literature. Another storyline is a dark tale relating to a mysterious manuscript, containing references to one of most famous horror story of all times, Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker.

After this brief diversion Stefán Máni turned back to crime novels, often with undertones of horror.

Before Black‘s Game was published Stefán Máni appeared in many interviews where he described his research into the Reykjavík underworld, and since then he has used this experience in various ways in his works. Even though The Ship (Skipið 2006) is not exactly a story about the underworld, one of the main characters comes directly from there. The Ship was awarded the brand new Icelandic Crime Novel Award, The Blooddrop, and is still one of Stefán Máni‘s best work. Since then he has received the award twice, for The House (Húsið 2012) and Cruelty (Grimmd 2013).

The Ship takes mainly place on the cargo ship Per se, traveling to Surinam. The ship, originally named Noon, is cursed and „infamous after police investigations into two murders and three suicides happing in just over two years“ (136). The crew takes its cue from this: most of the men are on the run from big trouble. The deckhand Sæli is in serious gambling depts, chased by a debt collector who calls himself Devil. Devil is a name assumed by Jón Karl Esrason, a seaman‘s son and a criminal, and he is an unexpected addition to the crew, fleeing from his competitors in the underworld. The engineer is a satanist who has read way too much of H.P. Lovecraft.

This is the situation when the ship sets sail and from there things can only get worse. When it is revealed that Jón Karl is a criminal the other members of the crew are shaken, but nothing can be done due to the sabotage of the ship‘s communication systems. And of course the weather is awful.

The characterisation is rich and interesting, indeed one of Stefán Máni‘s hallmark is his creation of memorable and unusual characters. Sæli and Jón Karl seem at first to be similar to Stefán and Brúnó in Black‘s Game, but this changes fast and they become their own men in a brand new story. It is particularly interesting to see how Jón Karl‘s character is built up, as the author draws clearly on his former novel and then recreates him in a completely new context. The style is also noticeable, Stefán Máni uses repetition to create a rhythm in the text, as seen in Tourist and his older work. The same scene is repeated from different points of view, and altered, and the same descriptions are repeated in different contexts. This creates a beat that follows the ships battling through waves, and the beat of the waves is a recurrent theme throughout the novel. This strong rhythm continues to make its mark on many of the later works, as will be discussed below. The imagery is layered and simple descriptions are used to set the tone, such as in the beginning of the book where Jón Karl‘s house is described: „At the entrance to the house the stone lions stand guard eternally and the long narrow windows flame like eyes in a beast that is neither old nor new, real nor imagined“ (15). Here is a taste of the devil himself and his many representations that appear throughout the story.

Characters, style and images all work together to create a mysterious and magnetic atmosphere. Stefán Máni uses themes from thrillers and horror novels, the ship sailing through the story is clearly a kind of a doomed ghost ship. In addition to this there are numerous references to stories about the many hardships of sailing the high waters together with more everyday descriptions of the realities of the seaman‘s life.

The dark undercurrent in The Ship strongly relates to satanism and the devil (these themes will reappear later), but in Lava of Dark Deeds (Ódáðahraun 2008) the author uses Nordic Mythology to spin his tale. Much like The Ship the story is full of symbolism, this time relating to the era of greed marking the years leading up the financial crash in 2008. This was partly funded by the privatisations of the banks and in many ways the novel was prophetic, published in early October, a few days after the country‘s economy crashed and burned.

Lava of Dark Deeds is the story of the drug lord Óðinn who finds himself in trouble and has to find money fast. He is one-eyed after a car crash and his assistants are named Huginn and Muninn – Óðinn is of course the name of the allfather in Nordic Mythology and Huginn and Muninn are the ravens that sit on his shoulders. After a botched business venture he intends to flee the country but is called to a meeting where he discovers that he is the son and sole heir of a rich man. Suddenly he finds himself in a key position in the Icelandic world of finance and soon spreads his wings using the same methods he employed as a drug lord. He gets rid of his opponents and gathers immense wealth, marries a trophy wife and starts supporting the arts – much to his own surprise. However, his past follows him, and this is where the mythology returns, as Óðinn senses his enemies approaching, the Ragnarök is near.

Apart from being an interesting story in itself, it is particularly powerful in light of the disasters in the Icelandic economy, disasters that have yet to be accounted for. The connection between the financial rise and crime is striking and eleven years later it is clear that this is still the case. Stefán Máni manages to describe the various complexes that make dubious dealings among the superrich possible while also writing a dark thriller about the mundane violence of the underworld crimes.

Hörður Grímsson

Greedism and crime are the subject of The Abyss (Hyldýpi 2009). The story is set in 2007 where the policeman Hörður Grímsson appears for the first time, he has since been a recurrent character in Stefán Máni‘s novels. The title refers to a scene where a ten year old boy, Sölvi, sinks into a deep and still lake and has a vision: a girl his own age who hands him something. Ten years later Sölvi is attacked and is found naked in a ditch. He remembers nothing from the attack but finds out later that a young girl disappeared that same day. He becomes convinced that this is the same girl he saw in the water and also that her disappearance has something to do with his attack. He tries to investigate the matter, against all odds; the girl was known to be ‚loose‘ and her disappearance is not taken seriously. Sölvi suspects his cousin, Bergur, and two brothers who are friends with Bergur. Sölvi, Bergur and the brothers all work together at an estate agency and they were all together on a boat on the lake, when Sölvi fell in. The threesome not only do dubious business deals, they also seem to have dedicated themselves to some kind of a philosophy of evil – also a kind of an abyss.

The Abyss is partly an investigation into the character of a young man, much like some of Stefán Máni‘s other works. Sölvi is rather lost, he is twenty years old and has no idea what he wants out of his life, or if he wants anything out of it at all. This is familiar from the author‘s early works, such as the young men in Hotel California and Black‘s Game, all are in some way pushed around by others, often due to their hopeless love for a woman, but also by dubious males.

Against these dazed and confused young men Stefán Máni places strong macho men, pumped up on steroids. They barge on without a thought, like Sölvi‘s comrades in The Abyss. Here they also stand as a symbol for the army of young financiers who so diligently created the crisis, men who stop at nothing in business, be it real estate or women.

As before the mysterious tones add to the story‘s impact, the description of the water and the events there is striking and the atmosphere is suffused with eerie tension.

As already mentioned, The Abyss is the first novel where Hörður Grímsson appears, although only briefly as a policeman who is investigating the girl‘s disappearance. It is immediately clear that he is quite unusual and seems to sense things that cannot be explained rationally. In the next novel, Harbinger of Death (Feigð 2011), his past is revealed to be highly dramatic. This was the subject of some media attention, much like Stefán Máni‘s investigations into the underworld before, only in Harbinger of Death the subject was a traumatic event in Icelandic history, an avalanche in the village Súðavík in 1995, where many were lost.

Much like The Ship, Harbinger of Death is suffused with threatening atmosphere. Also, the work is characterised by a powerful, thunderous rhythm appearing both in the subject matter and the text. This power appears in two main ways; in the forces of nature, the ocean, weather and the avalanche, and in Hörður Grímsson himself, who is the main character here. He is very tall and strong and in every way extreme, with long red hair and always dressed in a long leather coat. What he does is also over the top, both when he ‚runs amok‘ when trying to save people after the avalanche in the first part of the novel, and again in the final part, when he drives like mad through the west part of the country – bad roads and bad weather notwithstanding. Despite all this Hörður also has weaknesses, he suffers from asthma and psoriasis and is repeatedly bested by his nemesis, the steroid muscleman Simon, who is a drugdealer.

As already indicated Harbinger of Death takes partly place in the west part of Iceland, in Súðavík, and partly in Reykjavík. In the first part we are introduced to Hörður and his father, who together with the father‘s friend, Pétur, sink their boat as part of an insurance scam. The harbinger of death is present from the start, as Pétur is accidentally lost with the boat. His death is a hard blow for his wife and daughter: the former loses her mind and the daughter, María, loses control over her life in a different way. After the avalanche she becomes Hörður‘s girlfriend for a while, but she wants more than he can offer – dope – and she finds Símon instead.

A few years later we find ourselves in Reykjavík, where Hörður lives now and works as a police detective. Símon has also moved to the city and continues his shady business. As before it is difficult to pin anything on him, even though Hörður and his mates do their best. Here we also meet with Hörður‘s partner and friend, the lesbian Þóra who is a really cool character despite not being given much space, and Hörður‘s girlfriend Bíbí, who is pregnant and cries all the time.

In the third part, taking place a few months after the economic collapse, Hörður has moved back to Súðavík with Bíbí, trying to start over. Of course nothing goes as it should.

The novel is framed by two kinds of disasters in Iceland, one natural disaster and the other caused by greedy financers. In addition the ocean and stormy weathers are very present, also in the way they mirror machinery described with a mixture of sensuality and suspense. In the first part Hörður has a classic American car with a powerful machine, and Stefán Máni continually aligns the two, the mighty machine and the mighty man who drives it. Together these descriptions create the heavy rhythm that characterises the text, and can also be seen the mark of an impending death, or an uncanny dance macabre.

Stefán Máni continues to fuse horror and crime together in The House (Húsið 2012), which is of course a ghost story. The House is highly gothic, much like The Ship, and in both novels the author is preoccupied with the idea of evil. Evil is actually a regular theme in Stefán Máni‘s work (much like in Lovecraft‘s), as it is in the gothic novel, where some obscure threat is always present, either of this world or some other. In The House it is both. Houses and homes are the mainstay of the gothic novel, in addition to being the inspiration for Freud‘s famous essay on the uncanny, where the familiar and known can suddenly and surprisingly turn out to be horrible and frightening.

Such is the case in The House. The novel starts with descriptions of terrible murders in a remote house in Kollafjörður, not far from Reykjavík. A young man survives only to be haunted by nightmares of a man with a hammer. It seems that the house is possessed, many years later a young man with a dark and violent past is drawn to it. This young man, Theódór or Teddi, is the main character of the novel and also the representative of evil. Unlike Jón Karl or ‚Devil‘ from The Ship, there is no explanation or excuse given for Teddi‘s behavior, he is simply a scumbag and when he moves into the house in Kollafjörður with his family things can only go downhill. The evil suffusing the house finds a host and history repeats itself.

The novel takes place in 2007, same as The Abyss, and Hörður Grímsson is here also, this time in a larger role. He is investigating the death of an old man who is found dead in his home. The death is assumed to have been an accident but Hörður disagrees. Again we see that Hörður has an uncommon insight and he senses that something is not right. He has his eyes on Teddi and keeps him under close surveillance, not knowing how much is at stake.

What was so surprising to Freud in the early twentieth century is well known today; the home is not necessarily a haven, too often it is where the worst kind of violence is doled out. This is one of the subjects of The House: abuse and domestic violence. The horror novel, much like crime fiction, has been an important vehicle for investigations into social ills of this kind, where ghosts and dark powers are symbols for violence. As before, Stefán Máni avoids overdoing the symbolism, instead of preaching he offers insightful reflections on the evil that can reside in the human soul and the status of evil as a social threat and an outside force. This makes The House an impressive and convincing work and the story is saturated with various types of hauntings and a strong presence of darkness.

Hörður Grímsson is still going strong in Cruelty (Grimmd 2013), and just like in The House he is not the main character. Cruelty takes place in 2010 and the ginger giant has returned to Reykjavík. The story mostly takes place in the underworlds of Reykjavík, complete with musclemen and dope. Smári, a small time criminal with big dreams and bad luck, is the main ‚hero‘ of the novel. He manages to mess up one damned thing after another, and as such he is by now a familiar figure in Stefán Máni‘s work – a somewhat naive and lost young man who wants to become a big fish. A horrible childhood has marked him, and he is always an outsider. What makes him interesting is that he is a heterosexual transvestite who unexpectedly finds shelter with Inga, an unhappy housewife. She is well off and it is the unlikely friendship – yes, friendship – between the two that will radically effect both their lives.

Smári has big plans to make money and move out of the country, but messes things up so badly that he winds up being chased by two drug-gangs. When Inga‘s grandson is kidnapped Smári offers to find the kidnapper and so begins a complex car-chase across Iceland; Smári is on the heels of the kidnapper and behind Smári are two sets of gangsters. Finally we have the police, our friend Hörður Grímsson, who has some sympathy for Smári, much like the reader.

In Cruelty we learn more about Hörður Grímsson. In addition to being tall and eccentrically dressed his emotional life is also dramatic. He drinks too much and his relations with the hairstylist Bíbí is stormy – in fact it seems that Hörður is always in the midst of a storm.

There is more humour in Cruelty than in The House, despite the title. This is obviously a rather black humour, related to action films driven by a fusion of exaggerated violence, hardy characters and one-liners. Humour is present in all Stefán Máni‘s crime novels, to some extent. Here Smári is the representative of the tragicomic, but the musclemen and the drug lords get their share, particularly in the car-chase, when their observations and interactions are hilarious. Hörður is no exception, he gets his share of irony, with his dramatic moods and large size, and also the way he seems mystified by human relations. Stefán Máni manages the balance between humour and seriousness well, and this makes the novels so readable.

In Black Magic (Svarti galdur 2016), Hörður Grímsson is still a young police officer and meets Bíbí for the first time, when getting his hair cut. His courting is quite funny as Hörður is not really good at sensing ordinary people‘s emotions. However, he has another kind of sensitivity as he is psychic and sees the shadow of death. Hörður fears this talent and pretends it does not exist. This emphasis on Hörður‘s abilities is in tune with the plot of the novel, as mystic powers play a considerably role, the largest so far in Stefán Máni‘s work.

Unexplained murders are committed, where seemingly random young people kill a member of parliament and other prominent citizens without having any reason, nor memory of the deed. Hörður gets mixed up in the investigation as he literally runs into one of the killers and senses that things are not as they seem. Due to his talents he is also more receptive to the elements of the cases that have no logical explanations. Early in the novel he is examining the belongings of a small time crook who has vanished and finds strange things that seem to be a part of some magic rituals. Later on these things turn out to play a key role in the solution of the case. Another narrative line tells the story of two crooks and their communications with their ‚master‘ who is in prison.

Black Magic is a genre fusion, much like The Ship and The House, and as before Stefán Máni shows his ability to spin dark threads into the form of the crime novel. This was used extensively in the marketing of the novel, as its design was similar to the Bible (black cover and red-rimmed pages), complete with a cross on the front – only upside down.

Since then Stefán Máni has published two more books about Hörður Grímsson, Krýsuvík (2018) and Advent (Aðventa 2019).

Werewolves and Bulls

In between Cruelty and Black Magic Stefán Máni publised four novels where Hörður is not present. Two of them are young adult novels, The Heart of a Wolf (Úlfshjarta 2013), and its sequel, The Long Night (Nóttin langa 2015). As the titles indicate the subject is werewolves. The first novel tells the story of a young man, Alexander, who fancies Védís. She is the younger sister of his best friend and this is problematic. This is not Alexander‘s only problem, he has a difficult relationship with his family, drops out of school and is in general rather lost and depressed. And prone to rages. When drunk he loses control and beats up his best friend and as a consequence he is taken under the wing of an anonymous werewolf association who try to explain to him what he is. Alexander finds this hard to stomach, and of course this does not make his attraction to Védís any easier. Things get even more complicated when he is assigned to befriend a criminal, a werewolf, who has just been released from prison. He rejects all attempts to restrain the wolf and claims that the shape shifting is caused by damage in people, that is, people who have been raped and have never been able to confront it.

Despite a complete lack of wolves in Iceland there are many references to them in medieval writings, sagas and poetry. Nordic mythology is rich with wolves where the giant Fenrir is probably most famous. The theory in The Heart of a Wolf is that there is a wolf gene, making it possible for a tiny percentage of humanity to shape shift. This is supported with all kinds of historical and literary references. And the werewolves have anonymous association, clearly referring to alcoholics anonymous. The werewolf gene gives Alexander new and exciting powers: „He is not just a werewolf – he is a superhero!“ (159).

It turns out that Védís also has a crush on Alexander. She is, much like him, a temperamental loner who has problems connecting with people. In The Long Night Védís is given more space, and it turns out she is also a werewolf. The novel also introduces a group of people who hate werewolves and intend to exterminate them. Finally there are issues between different groups of werewolves, as already indicated in the first novel.

The werewolf novels are an example of how Stefán Máni works with legends and monsters in an interesting and insightful way. He avoids simplifying things and offer complex characters and different sides of what is considered to be horrible or threatening. But when it comes to pure evil there is no excuse. In Black‘s Game Bruno is the representative of evil, something evil is lurking in The Ship but it is first in The Abyss that speculations about the nature of evil really take flight, continuing in The House, Cruelty, Black Magic, and Krýsuvík. Evil is often related to crime, although not in a general way, rather to utterly immoral crimes committed by the mercilessness of those who have power and enjoy using it. In The Abyss, taking place in 2007, a clear connection is made between greedism and evil, taking the form of the men in suits who enjoy torturing young women. Greedism is also linked to crime in Lava of Bad Deeds and even though greedism is not per se discussed in The House, the setting is the peak year of the era of greed, 2007. The economic crash is present in Harbinger of Death, in addition the story starts with a disastrous plot to make money. All these novels contain criminals or evil-doers who do not hesitate to harm others if they can benefit in some way. However, it is only in Little Deaths (Litlu dauðunum 2014) that Stefán Máni actually focuses on the crisis. The main character is a banker, Kristófer, who loses his job and attempting to avoid becoming bankrupt involves himself with criminal activity. He hides all his troubles away from his wife and on the run from himself and his troubles he takes her on an unexpected holiday to a summer house. This ends badly. The events of the novel seem always on the borders of the supernatural, Kristófer gets lost on the way to the summer house and the couple wind up in a gathering of motorcyclists. At the end of the novel Kristófer is lost in a dark cave, pursued by some sort of a demon.

The Little Deaths is, much like Tourist, a kind of an allegory, but neither manages the impact of Stefán Máni‘s other novels. His symbolic references work better when not as tightly bound, roaming free among dark deeds, their causes and consequences. Kristófer is, however, an interesting example of the crisis of masculinity that characterises most of Stefán Máni‘s work. As already discussed his main characters are usually young men who are rather lost. Many of them wind up as criminals due to this, apart from Hörður who winds up as a cop. The others, such as Stefán, Óðinn and Smári, all want easy money and escape from the limits of small society in Iceland. The same goes for Rikki, who is one of the main characters of The Bull (Nautið 2015).

Much like many of Stefán Máni‘s former works, The Bull is highly suited to cinematic adaption, as it is full of detailed highly visual descriptions and settings. In the first chapter, framing the story, two foreign girls are travelling through Iceland. Their car breaks down and there is no cellphone reception, so they walk to the nearest farm seeking help. It is the middle of a sunny day, and this setting emphasises the horror they find when they come to the farm Uxnavellir.

After this introduction we go back in time and meet the two main characters of the novel, Ríkharður, called Rikki, and Jóhanna, called Hanna. They are both creatures of the underworld of drugs and violence, so familiar from Stefán Máni‘s former novels. Hanna is engaged to a drug lord, Rikki is his henchman, and both dream of a better life. Their situation is far from pleasant, Hanna was born on a farm and abused by her father since she was a teenager. As before Stefán Máni shows his best when describing harsh realities studded with mysterious undertones.

The ticking of a clock is heard throughout the story, breaking the narrative into chapters going back and forth in time. Still it is clear that for the characters there is no movement forward in time, they are prisoners of their social situations and cannot move on or have any kind of a future. Time, in this world of dark deeds and violence, is thus a key element in the novel‘s structure. Already at the end of the first scene time appears as a threat: „The clock on the wall above her. Seconds pick at her head, pointed and harsh. Time is a merciless bird trying to cleave her skull, open up her head (20).“ It is mainly Hanna who senses the power of time in this way. She compares the ticking of the clock in her old home to a metallic bug who „crawls, moving its stiff feet to the rhythm but always stands still (210).“ The Bull is another theme and appears regularly. In this way the imagery of the text is conflated with the subject of the story, slowly building an atmosphere of enclosure and eerie threat.

Gothic shadows

The novel The Shadows (Skuggarnir 2017) is a horror novel, where the various hauntings of Stefán Máni‘s novels are now completely in control. A young woman, Kolbrún, is the main character. She is in a relationship with a slightly older man, Tímoteus, called Timmi. Timmi is a photographer with big dreams, much like many of Stefán Máni‘s male characters. He gets Kolbrún to go with him on a tour into the highlands to find a hitherto unknown desolate farm to photograph it for the cover of a book, thus ensuring him immediate fame and a bright future. The hike is in every way badly prepared and nobody in the nearest settlement seems to know about the farm. However, they find it, and of course it turns out to be a haunted house.

The story is in many ways a rather traditional ghost story complete with symbolic undertones so often found in Stefán Máni‘s work. This does not change the fact that the novel is a powerful work, the author having shown his ability to create an overwhelming atmosphere and convincing characters. Kolbrún and Timmi both carry their emotional baggage. Kolbrún is sensitive, delicate and emotionally imbalanced, as a result of a difficult relationship with her parents. She dreams of having a family of her own. Of course she works in a kindergarten and this is where she meets Timmi, through his daughter. Timmi is a real cool guy on the outside, but at home he is the victim of domestic violence. He is a classic image of a man who is unable to rise to the masculinity he so longs for: fame eludes him and in addition he is beaten up by his wife, Anna, who orders him to break off the relationship with Kolbrún, or else. Thus the journey is doomed from the start, being both a badly thought out search for an unlikely fame, and an escape from unbearable situation.

The story shifts between Kolbrún and Timmi in addition to backflashes. At the beginning Kolbrún is stuck in a nightmare of shadows and dead infants – left out to die from exposure. She wakes up as they approach the village Kópasker, their starting point for the hiking to the highland. In Kópasker she meets a mysterious old woman dressed in black. Also she puts and envelope in the post box, containing her application for university. Both appear at the end of the novel in a metafictional twist. Such stories within stories are a popular feature in horror novels.

Stefán Máni manages the classic gothic elements with dexterity and adapts them to his own story. The Shadows refers to the folklore of the past as well as today, showing how the beliefs of the past never disappear. Instead they take on new forms in the modern reality which turns out to be not so far from the distant lore.

In the same way Stefán Máni‘s oeuvre is highly interesting in the light of traditional separation of popular culture and Literature with a capital L. His work crosses any such distinctions and reveal how limited they are. The first novels leaned more towards high culture, but since Black‘s Game Stefán Máni has turned towards genres, crime fiction and horror novels, that are usually considered low culture. His path is contrary to many who start their careers writing popular novels while aiming to join the ranks of Literary authors. Although Stefán Máni uses classic subjects of the crime novel and the horror novel his books are no less interesting, quite the contrary, his oeuvre proves that in capable hands such stories can be just as effective and important.

úlfhildur dagsdóttir, December 2019

A Worker in God’s Wine Yards: or the ability to notice the insignificant and small. On the Works of Stefán Máni

I

At the end of Stefán Máni’s novel, Ísrael: Saga af manni (Israel: Story of Man) (2002), the protagonist Jakob, nicknamed Israel, is discussing politics with his dinner guest who is the assistant-financial-manager of an international pension fund and also has his hand in politics. His name is Haraldur and he is nicknamed “the city mayor of tomorrow”. The debate takes place at the dinner table where the stout future leader is pictured grotesquely as he munches his food loudly and does not seem to know or to be willing to follow basic table manners. Perhaps this is because his motto is honesty and candour, but in any case he does not hesitate to mock the working people and their world. When Jakob points out to Haraldur’s wife, the editor Líf, the possibility of writing articles about the mundane, such as potatoes or cloth-hangers, for her glossy magazine, she reacts by patronizing him, saying:

Það er kannski gjöf guðs til hins fábrotna verkamanns, þessi undarlegi hæfileiki að geta komið auga á hið ómerkilega og smáa í umhverfinu, á hluti og fyrirbæri sem við, sem hlutum menningarlegt uppeldi og eigum langskólanám að baki, förum á mis við í amstri dagsins [...] hún sagði mér, hún Hrefna sambýliskona þín, Jakob, í trúnaði reyndar, að þegar þið kynntust hafir þú verið rótlaus og drykkfelld barfluga sem átti margra ára flakk og farandverkavinnu að baki, og kallaði sig þar að auki Ísrael, er þetta satt? (248)

[Perhaps this is god’s gift to the simple worker, this strange ability to be able to notice the insignificant and small around us, to see things and phenomenon that we, who had cultural upbringing and studied at universities, miss in our everyday life [...] your partner, Hrefna, she told me, Jakob, just between the two of us actually, that when you met you were a rootless continually inebriated bar-fly and had behind you many years of aimless wandering, working here and there, and calling yourself Israel to boot, is this true?]

Jakob denies having been a barfly, but does not hesitate to announce that he is a migrant worker through and through, “and will always be a migrant worker, deep inside, ... and am proud of that, as I am one of the last, ... even the last one” (248). For “existence has been swept away from the migrant workers, ... the fishing quota system, less fish, industrialisation and cheap foreign workers have seen to it that Icelandic society is clear of this damned plague” (253). This plague has of course a centuries old tradition in Iceland, and thus the name Israel is suitable as it contains the story of a nation.

Ísrael: Saga af manni is the author’s fourth novel. The first, Dyrnar á Svörtufjöllum (The Doors to Blackmountain) (1996), is very short and formally more akin to a book of poetry than a novel. His second novel, Myrkravél (Dark Machine) (1999), garnered some attention, but it was not until the third novel, Hótel Kalifornía (Hotel California) (2001), that readers and critics really started to give their attention to this young author. Ísrael fulfilled the promises given by Hótel Kalifornía, and it is clear that this young writer has everything needed to become a permanent voice in Icelandic literary and cultural discussion.

As apparent from the discussions in Ísrael, the world of Stefán Máni is the world of the worker. Myrkravél, Hótel Kalifornía and Ísrael are all told from the viewpoint of the worker, and a look at the biography of the author makes clear that he is speaking from his own experience. In his essay here on this website he describes how he stood with his hands sunk deep into the fish-containers and thought about whether he should get going and publish Dyrnar á Svörtufjöllum. Still, it was not until Ísrael that a certain pride appears. While the protagonist of Myrkravél is a man who has serious mental problems and the narrator of Hótel Kalifornía seems to be a bit of a simpleton, Jakob is a proud man who refuses to be trodden on. He is a hardened man, a tough worker who finds it easy to adapt to different types of labour and perform them with efficiency. This is particularly noticeable in his connection to machines; he reaches a special relationship with them, understands how they work and persuades the most stubborn machinery to cooperate. His class-consciousness and knowledge of the political landscape is considerably more noticeable than that of the other narrators, and he also has a dream of guiding his people. When Líf asks – ironically – if the name Israel refers to Jakob’s wish to become a head of a family or a king with thousands of descendants, Jakob answers that he had a dream about “migrant workers uniting under the sign of a particular ideal, forming some kind of a union or movement, not a traditional labour-union or a political party, but some kind of a brotherhood” (249). Jakob is a man who stands at the border of two worlds or times, and even though his idealism is still dear to him, he is fully aware of that this way of thinking is not valid any more. The sincere political fervour has disappeared, just like the migrant workers, and Jakob is left behind. As a representative of disappeared ideals and a worldview he must die.

II

The worker’s world is far away in Dyrnar á Svörtufjöllum, and it is the only story by Stefán Máni told from the viewpoint of a woman. The story is a rather typical beginner´s work, experimental in style and design, self-published by the author who designed it himself. Inside of a mountain a group of people live, the one who tells the story, her parents and grandmother. Something has happened and the world outside has become uninhabitable, the future of mankind rests on these five souls – even though the grandfather is dead, his rebirth is imminent. The text is very short, and as said earlier is more reminiscent of a long prose poem or a monologue in a play, than a novel.

The same concise style characterises Myrkravél, while being a considerably longer work. Myrkravél is a kind of a short novel, or a novella, describing the sick world inside the mind of a young man. The story is told in the first person and the narrator is sitting in a prison claiming not to be human, to be a dark machine. He narrates his life’s story from childhood, and it appears that he has always been a strange child. Finally he is thrown out of his home and after this the descent is fast. He finds it hard to manage within society and even though he is twice hired for construction work and in that way attempts to lead a routine life, the chaos within his soul continues to rise, until finally he does the terrible deed that he has been imprisoned for. The novel is in many ways interesting, perhaps a little youthful at times, but clearly indicating that an ambitious author is on the roll.

Myrkravél illustrates well the loneliness characterising the work of Stefán Máni, where the isolation of the narrator breaks out in violence against his surroundings and finally a human being.

The girl in Dyrnar á Svörtufjöllum responsds to loneliness by isolating herself further, while the narrators of Hótel Kalifornía and Ísrael fight against their isolation by desperately seeking a friend, girlfriend, family. Stefán in Hótel Kalifornía dreams about romantic relations with the other sex, but is sadly unable to fulfil such dreams, as he is incapable of understanding the gap between them and reality. Jakob in Ísrael finds it easy to relate to women, while the relationships do not always work out the way they should, and even though he has started to live rather happily with that same Hrefna who hosts the aforementioned dinner party, it is clear that he is still uneasy and has not found his place.

The gloomiest isolation is the one of Hótel Kalifornía’s narrator, when he at the end of the story walks alone down the decrepit corridor of a club. Earlier in the story it had become clear that this night will not be a good one. Hótel Kalifornía is related to the traditional bildungsroman, as apparent from the narrator’s unsuccessful relations to women. This embarrassment of the narrator in Hótel Kalifornía did not endear me to the book at the beginning. I thought that maybe there is already enough of these endless stories about young men, their unexciting complexes and ideas of life and wondered if I would really have to, yet again, read a story about some guys in an existential crises and their monotonous lives.

Except Stefán Máni surprised me nicely by writing a story that manages to stand out from that otherwise too standardized group of novels. For one of the noticeable things about Hótel Kalifornía is that the protagonist does not mature at all. And this is the charm of this otherwise modest story, the young hero, the young man on his pointless way through life, who according to the formula should be a different man at the end of the book from the one in the beginning, is still as pointless as he was at the start.

The first part of the novel describes how the protagonist, the narrator Stefán, lives his monotonous life. He works at the local fish-factory, controlling a machine that chops the heads off cods. Usually it is so busy that he also has to work Saturdays. This does not prevent him from going out on formulaic binges with his friends during weekends, where Icelandic “Black Death” (Brennivín) plays the main part. As the story moves on it comes to light that the narrator has a rather special status within the fish-factory-society and is considered to be a little peculiar. For an example he goes for walks. And in one such he recalls a memorable stay in the capital city, where the boy was meant to go to a good highschool. He himself dreamt of going to trade school, as he has a way with everything to do with electricity. The years in school – inviting yet another bildungsroman cliché – ends in a fiasco and Stefán escapes back to his perfectly monotonous life.

The style is disciplined and quite monotonous at times, suitable for the monotonous life of the narrator. To start with this was a bit difficult but further into the story the reader starts to experience the changes in Stefán’s life, hopes and dreams, tiredness and desperation apart from the relentless ennui and hopelessness. The music he listens to plays a considerable part and has its role in adding to the nuances and opening a way into the mind of the narrator. The main tune is of course “Hotel California”, but instead of having the song sounding continuously, lines from it appear only occasionally, most importantly at the end, where it has a keyrole for the conclusion of the story.

III

It has been claimed that the novels of the youngest generation of Icelandic authors are characterised by some kind of a return to realism, and the word neo-realism has even been used in this context. This doubtless refers to the novels of Auður Jónsdóttir, Gerður Kristný, Guðrún Eva Mínervudóttir and Mikael Torfason, but while Andri Snær is certainly a member of the youngest generation his work hitherto cannot be called realist. I am not fully convinced that this definition holds, for while the fiction of these writers is for sure often characterised by some kind of realism, this realism is a highly demarcated phenomenon, and this demarcation appears clearly in the works of Stefán Máni. In fact an unusual approach to realism appears as well in the novels of Auður, Guðrún Eva and Gerður Kristný, where it always seems to be in some kind of a danger, at the brink of exploding and becoming something quite different. Just like it is a barely tame animal in a cage.

And this feeling began to grow, the further I read myself through the corridors of Hótel Kalifornía. Under the dead calm surface a tension is lurking, breaking out at times – more often than not taking the form of a drunken vomit. The struggle with realism is even stronger in Ísrael, where the author guides the reader through long meticulous descriptions of working methods and job descriptions and the everyday details of the narrator’s life. And it is exactly this grip on the everyday, this feeling for the mundane, or, to use the author’s words again, “this strange ability to be able to notice the insignificant and small around us” that give Stefán’s moderate style a cunning power that at its best has a hypnotic effect on the reader.

An example of such a description is the story about the dishwashing job in a high-class restaurant in Reykjavík. The scene opens in front of the restaurant, located in a one hundred year old brewery in the old east part of town. We follow the visitor through a heavy iron gate that opens at six a clock in the afternoon and down the red carpeted corridor, into the reception and from there into the cognac-room. After a short stop there the reader finally enters the dining hall, which is described minutely, and waiters are continually zooming in and out of the kitchen. It is not until on the fifth page of the chapter that the reader gets to see the kitchen and Jakob’s working conditions, described just as minutely as the inside of the restaurant. Stefán leads confidently and I followed him hypnotized through the maze of the house, listening to the arguments between waiters and learned ways to clean the scorching washing machine. The hand is unhurried and skilful, just like Jakob’s way with the machine and it is clear that the author has taken a large step forward in comparison with Hótel Kalifornía, where similar detailed descriptions did at time become a little heavy handed and tiring.

Another similar scene is the chapter in the printing house, serving as a kind of an anchor to the narrative, beginning with a long prehistory of the printing house and its founders. The descriptions of Jakob’s relationship with machines and the staff are quite brilliant.

It is in such drawn out and thoughtful descriptions that the idea of realism breaks down. A three-page description of a book’s travel through the birth canals of the machines stretches the illusion of realism too much. It begins thus:

Í bókbandsdeild prentsmiðjunnar var samankomið ótrúlegt safn af vélum, bláum, gráum og grænum, sem gengu fyrir rafmagni og lofti, skröltu áfram og soguðu og blésu, flestar orðnar lélegar, fornar í skapi og pínulítið sérvitrar, tannhjólin slitin, keðjunrnar slakar, öxlarnir bognir og reimarnar trosnaðar, en þær gerðu sitt gagn og unnu oft myrkranna á milli við að skera, brjóta, sauma, taka upp, líma og hefta framleiðslu fyrirtækisins, allt frá einföldum bæklingum og eyðublaðaheftum til dýrra glanstímarita og fallegra, innbundinna bóka. (92)

[In the department of bookbinding in the printing house an unbelievable collection of machines were located, blue, grey and green, powered by electricity and air, clattering on and sucking and blowing, most worn out, with their set ways and peculiarities, the teeth eroded, the chains slack, the axles bent and the strings frayed, but they did their job and often worked 24 hours, cutting, folding, stitching, taking up, gluing and stapling the product of the company, everything from simple brochures and forms to expensive glossy magazines and beautiful, hardcover books.]

This personification of the machines continues, and as already stated, Jakob has a special talent when it comes to machinery.

A teenage son of the owner, Rósi Brekkan, works at the press, he is a dropout from school with hair dyed in exaggerated colours and funny ideas about the world. He is not a good worker but makes it up with his talent for daydreaming, like the one where “the printing house would not be a printing house at all but just a delusion, we would not be free workers but imprisoned for life in one of the most secure prisons of the universe” (145). Here there could be a reference to the idea that everybody is the prisoner of a delusion; not free workers but imprisoned for life in the secure prison of modern society. The personification of the machines and the boy’s invention are also examples of how the nuances of fantasy sneak into the novel. Fantasy in Icelandic literature grew stronger in the nineties and even though the works of aforementioned young authors cannot be called fantastic, many of them are marked by this capitulation of realism, appearing so nicely in the hyper-meticulous realistic descriptions of Stefán Máni.

And Rósi’s idea is actually not so far from the approach to realism that Stefán Máni creates in his work, with its devious descriptions and the relentless documentation of everyday events. The reader really starts to get the feeling that this must all be a delusion.

© Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir, 2003

Articles

Interviews

Tine Maria Winther: “Fra fiskefileter til forfatter” An interview in Danish

Politiken June 13, 2009

Awards

2025 - The Drop of Bloood, the Icelandic Crime Writer´s Award: Dauðinn einn var vitni (Death Alone was a Witness)

2014 - The Drop of Bloood, the Icelandic Crime Writer´s Award: Grimmd (Cruelty)

2013 - The Drop of Bloood, the Icelandic Crime Writer´s Award: Húsið (The House)

2007 - The Drop of Bloood, the Icelandic Crime Writer´s Award: Skipið (The Ship)

Nominations

2024- The Drop of Bloood, the Icelandic Crime Writer´s Award: Borg hinna dauðu (The City of the Dead)

2023 - The Drop of Bloood, the Icelandic Crime Writer´s Award: Hungur (Hunger)

2022 - The Drop of Bloood, the Icelandic Crime Writer´s Award: Horfnar (Disappeared)

2008 - The Glass Key, the Scandinavian Crime Writer´s Award: Skipið (Th Ship)

2006 - The Glass Key, the Scandinavian Crime Writer´s Award: Svartur á leik (Black’s Play)

Hungur (Hunger)

Read moreKlukkan tifar og einhvers staðar í skuggum borgarinnar leynist sjúk sál sem er drifin áfram af óseðjandi hungri.

Mörgæs með brostið hjarta: Ástarsaga (A Penguin with a Broken Heart)

Read moreMörgæs með mannlegar tilfinningar, ástfangin en um leið full af kvíða, leitar að tilgangi lífsins

Skuggarnir (The Shadows)

Read more

Nautið (The Bull)

Read moreGod of Emptiness (excerpt)

Read more

Litlu dauðarnir

Read more

Grimmd (Cruelty)

Read more

Úlfshjarta (Wolf´s Heart)

Read more

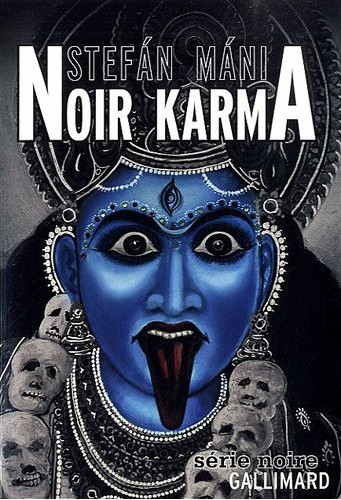

Noir Karma

Read more