Bio

Aðalsteinn Ásberg Sigurðsson was born in Húsavík, north Iceland on the 22nd of July, 1955. He grew up on the farm Öndólfsstaðir in Reykjadalur, in the same region. Aðalsteinn studied Icelandic language and literature at the University of Iceland in the winter of 1976-1977. He also studied music- and drama, and attended courses in film script making and playwrighting.

From 1980 Aðalsteinn has dedicated himself to writing and to music. He has published a number of poetry collections and children's books besides working as a translator. Aðalsteinn's first published work was the poetry book, Ósánar lendur, in 1977. Aðalsteinn Ásberg was one of the founders of the folk music group Vísnavinir and he also played in the band Hálft i hvoru. He has published music for children along with his wife, singer Anna Pálína Árnadóttir who passed away in 2004.

Aðalsteinn Ásberg was the managing director of the Union of Composers and lyrics 1988-1998, president of Nordisk Populærautor Union 1993-1995 and president of the Writers Union of Iceland 1998 - 2006. In 2023 Aðalsteinn was awarded from The National Broadcasting Service´s Writer´s Fund, for the year 2022.

Author photo: Nökkvi Elíasson.

About the Author

María Bjarkadóttir: About the works of Aðalsteinn Ásberg Sigurðsson

Aðalsteinn Ásberg Sigurðsson began his career as a poet and his first poetry book was published in 1977. It was followed by five other books of poetry and a poetic novel, Ferð undir fjögur augu (An Intimate Journey) in 1979. Since the nineties, Aðalsteinn Ásberg has almost exclusively taken to writing children''s books, but the poet still finds outlet both in poems in the children''s books; and in rhymes and songs for children as well as other lyrics. His subject matter varies, but both his poems and his prose are inspired by folklore and folk beliefs, among other things. The style of his work is poetic, and the search for identity is a recurring theme. With time his style has become more defined and focused, showing signs that the author seeks to further his personal development and that of his readers through his work.

Aðalsteinn Ásbergs‘s first poetry book, Ósánar lendur (Unsown lands, 1977) bears the mark of a young poet still developing his style. The style is often undecided and he uses different poetry forms. The poems are both rhymed and non-rhymed and the subject ranges from nature to politics, no doubt due to the turbulent time in which they were written and published, which the work can be seen to reflect. In his next book, Förunótt (Journeying Night, 1978) the poet seems to have decided on a particular style and hence the work is more coherent as a whole. The style is concise but descriptive and the reader senses the poet''s search for self through the poems. In Gálgafrestur (Reprieve, 1980) the style is similar to Förunótt, but this time the main source of inspiration is folk beliefs as well as everyday life; the contrast between the two gives the poems a darker, more sombre tone than before. Fugl (Bird, 1982), as the title suggests, is markedly lighter than Förunótt; the tone is faster and more playful although the reader can still detect in it the poet''s search for self.

The fifth book of poetry is Jarðljóð (Earth Poems, 1985) in which everyday and modern themes begin to appear among the poet''s earlier preoccupations. He looks back at his youth and the city, depicting a stark contrast between nature and technology, the past and the present. Aðalsteinn Ásbergs''s last poetry book is Draumkvæði (Dream Poems) from 1992. The tone is considerably quieter than in his previous books, and snow, fog, and night are among its recurring themes. In this work the poet seeks to combine the past, the present, and the future and, in contrast to his earlier works, it shows a certain level of stoicism. Ferð undir fjögur augu (An Intimate Journey,1979) is Aðalsteinn Ásbergs‘s first and only novel for adults and it has the same stylistic qualities as his poetry books. The novel tells of a young student in search for himself; he does not know what he wants or which direction his life will take. The use of language is poetic and the plot of the story is wholly dependent on the thoughts of the main character. Peculiar, often distracting images are conjured, which stimulate the reader and seem to be meant to provoke thought.

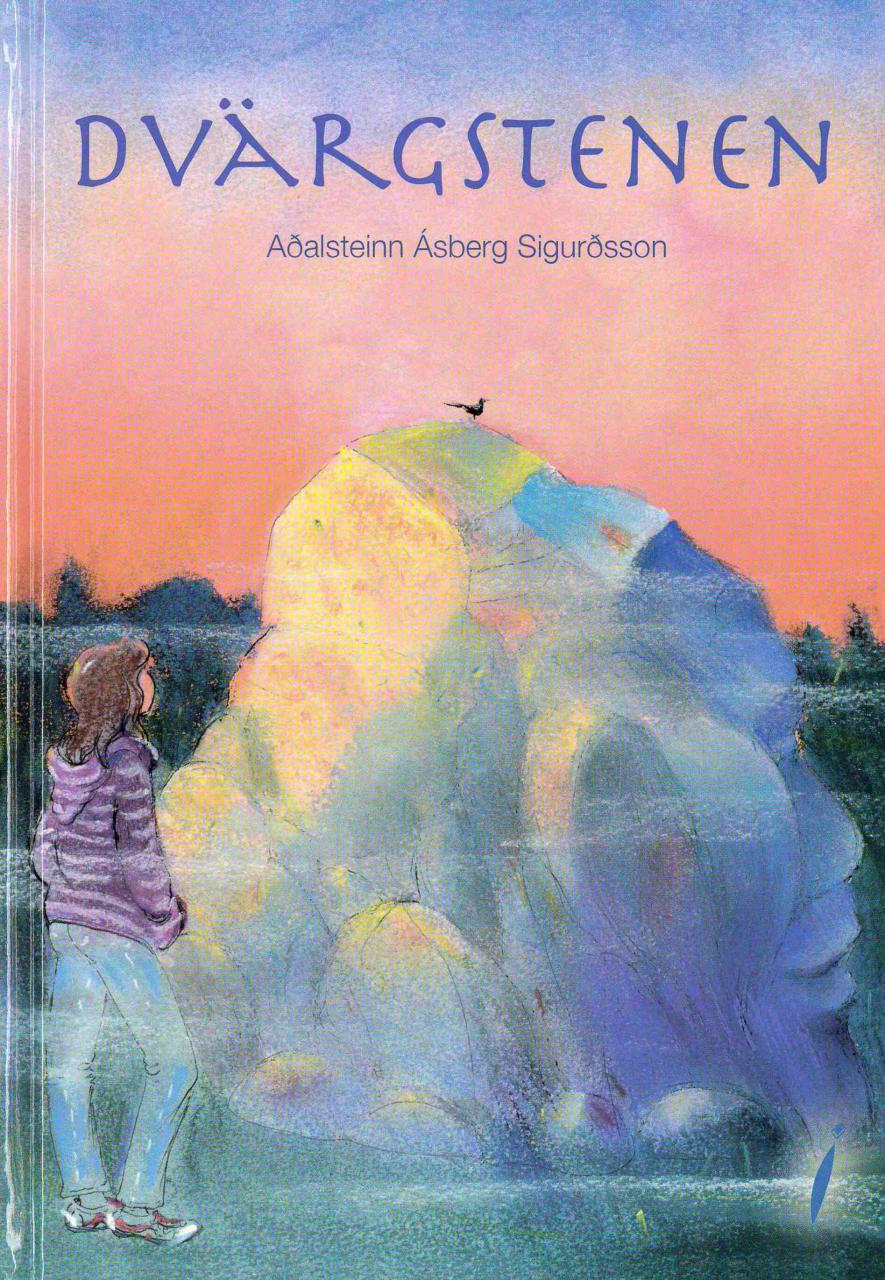

Dvergasteinn (Dwarfstone, 1991) is Aðalsteinn Ásbergs''s first book for children and its protagonist is the girl Ugla, who stays in a small village with her grandmother for a couple of weeks one summer. The grandmother lives in an old house which has a long history. There is a big rock in the garden and when Ugla finds a strange glittering stone next to it, she is suddenly able to see the fairies who live in it. The glittering stone enables whoever carries it to see the fairies and a world that humans are normally unable to see.

The room that Ugla stays in at Fairy Stone, as her grandmother''s house is also called, used to belong to her grandmother''s sister Sæunn, who died young. Ugla finds Sæunn''s diary in which she tells of her encounters with the fairies in the garden, and how one of them has lost his glittering stone and is condemned to live as a human until he can reclaim it. Sæunn believes herself to be under a spell and is convinced that the illness that she dies from is caused by the fact that she is unable to help the fairy return to his home. Later, in her grandmother''s living room, Ugla discovers a glittering stone, identical to the one in the dream and guesses that this must be the stone that the fairy has lost. She asks her friend Orri to help her find the fairy, who currently is living in the guise of a human in the outskirts of town. The kids successfully return the stone to the fairy, who is very grateful to them and can finally return to his home.

The book is a light and entertaining read, although it also tackles more serious issues, in the story of Sæunn''s death, and in the plight of Gaumur the fairy, who is unable to return to his home. The fairy''s story mirrors Ugla''s own life, because she is alone in the beginning like him, and in a strange place. As the story progresses, she becomes more fascinated by her grandmother''s house, the town and the stones in the garden. When in the end she returns home to her everyday life, far away from Fairy Stone, Gaumur is also allowed to go back to his home, away from the everyday world, back to the world of elves and fairies. The story also describes Ugla''s realization, that however exciting the glittering stone may seem to her because of the powers it gives her, returning it and helping Gaumur go back home is still the right thing to do. She learns that she should sometimes set aside her own wishes in favour of other people''s needs and that selfishness never pays.

Aðalsteinn''s next story is titled Glerfjallið (Glass Mountain) and was published in 1992. It tells of the brothers Halli and Frikki, and their aunt Gúndína who is a remarkable lady. Gúndína agrees to look after the brothers while their parents are on a trip but before they leave, she gives Frikki a peculiar music box which will have a deep effect on their lives. On Gúndína''s first night in the brothers'' house, Frikki disappears and the music box with him. Halli and Gúndína embark on a great mission to try to find him and the search leads them to a strange underground country where giants, elves and all sorts of strange creatures live. To guide them along, they carry a drop-shaped pearl, which points them in the right direction by playing the same tune as the music box does. They then begin to realize that Frikki''s disappearance had something to do with the music box. The tune the music box plays is an integral part in the plot development of the story. Gúndína knows the lyrics to the tune and they discover that it can also point them in the right direction if they manage to interpret it correctly.

In their travels through this strange country they meet many creatures who either help them or try to distract them. Finally they reach a high glass mountain where the creatures skarmýrar live, who are a cross between a raven and a human and seem rather dangerous. They discover that these creatures have captured Frikki because they think he stole and ruined the music box which somehow holds the key to happiness and prosperity in the kingdom where the glass mountain is. Halli and Gúndína manage to free Frikki, but as they are fleeing from the mountain they run into an old man who tells them that the only way they can save their country and get back home, is by returning the pearl to the music box which will then resound through the land as it was originally meant to do. Halli takes on this task, but in order to return the pearl he needs to climb up a tall ladder, and with each new step has to face frightening shadowy figures and overcome his fear to be able to continue. All goes well in the end, the pearl goes back to its place, and Halli, Frikki and Gúndína can go back home after having saved the strange country from darkness and woe.

Glerfjallið is a first person narrative and like Dvergasteinn it is in some ways a coming of age story about a child who learns that sometimes one needs to make sacrifices to be able to help other people. This story however, is more complex than the earlier one, since it is also the story of how Halli conquers his fear. The ladder he climbs is symbolic for this fear and it also shows that if one is to find the right path through life, one should not give up whenever there are obstacles.

Álagaeldur (The Fire Spell, 1993) is in many ways a more typical book for kids and teenagers than Aðalsteinn''s previous books. The protagonists of the story are the friends Óðinn and Logi who are later joined by Árni, Óðinn''s cousin from Denmark. An old blacksmith in town named Kobbi tells them the story of a treasure, said to be buried in a hill outside the town, and that if the hill were to be disturbed, the town would be set on fire. The story awakes the friends'' curiosity and they go out camping by the hill in order to try their luck there undisturbed. Parallel to the story about the hill there are descriptions of the boys'' interactions with other townspeople, in particular with old Kobbi and the town bully, Danni. The boys are constantly fighting Danni but in the end he turns out not to be as bad as he seems.

When the three mates start digging into the hill they soon discover that the story that Kobbi told them has come true: old Kobbi''s workshop is on fire. But the fire turns out not to be caused by the folklore but by an arsonist, Danni''s brother, in an attempt to scare him. The three mates begin to suspect the truth, although only Logi knows who the culprit is, because he has Danni''s confidence and he has told him the whole story. The three friends go to the house by the hill and find the arsonist hiding there. He sets the house on fire before deserting it, but the three mates entrap him and hand him over to the police.

This story tackles certain youth problems, particularly those that have to do with relating to other people. The cousin from Denmark and Danni both show that it is possible to become friends with people one does not think much of in the beginning, and that people can be friends and have much in common in spite of different backgrounds. This is also borne out in the friends Óðinn and Logi themselves. Logi lost his father when he was young and lives with his mother in a small basement flat. He is rather poor, yet he simply deals with things as they come and generally seems more content with his life than Óðinn, who has both family and money. It is mainly Óðinn who matures in the story and learns to appreciate other people''s good qualities.

Furðulegt ferðalag (A Strange Journey 1996) is Aðalsteinn Ásbergs''s fourth book for children and its protagonist is younger than in earlier books. It tells of Börkur who is about to move house and does not want to. One night he sees a funny creature in his backyard, and when he starts to investigate he discovers that this is a faun, sent there to save the trees in the yard from the new owners, who are going to cut them down. The faun, Pansjó, wants Börkur to help him and tells him to get more people to join them, because a huge task awaits them. The trees they need to save are the so-called lifespirit trees, special trees that have a soul. Börkur enlists the help of his friend and, unexpectedly, his little sister joins them. Pansjó creates an air of mystery around this task and they encounter many riddles. They need to fight evil opponents and loose one tree in the process, but with the help of some faithful friends they manage to bring the other trees to safety in a small clearing near Þingvellir natural park, where they take root.

In this story Aðalsteinn Ásberg continues working with the theme of his two previous books; that not all things are as they seem in this world. The journey with the trees is similarly symbolic for the children''s journey to maturity, and shows how they learn to deal with problems that arise on the journey, as in life. The story of the trees that need to uproot themselves and move echoes Börkur''s life, who like them has to uproot himself and move away from a place that he loves. The trees show him that it is not necessarily a bad thing; their new home isn''t any worse than the old one and when Börkur realises this he is not so negative about having to move.

Brúin yfir Dimmu (The Bridge over Dimma, 2000) and Ljósin í Dimmuborg (The Lights in Dimma City) 2002) are Aðalsteinn Ásbergs''s latest works for children. Here, the style and the handling of the material are more decisive than in earlier books, the style has been perfected, but the stories are considerably different from the earlier works. They both take place in a complete parallel reality that the author has made up himself. The books tell the story of Kraki, his little brother Pói, and their cousin Míría, who are of the species vöðlungar. In the first book they all live together with Kraki and Pói''s parents at Stöpull by the bridge over the river Dimma. Vöðlungar are creatures who resemble humans and have many things in common with them. Yet humans are their worst enemies and are a great danger to them. It is possible to pass between the human world, or Darkworld, which is the name that vöðlungar have given the world we live in, and the world of vöðlungar by a variety of routes, however most of them are dangerous and rough. Kraki and Pói''s family has long had the task of guarding the bridge over Dimma to the human world, because ancient prophesies have foretold that in the future a great monster will come from Darkworld and lay to waste the world of vöðlungar.

In the first book, Kraki, Pói and Míría visit Darkworld. Kraki finds an old journal in a library that is discovered by accident inside a secret room at Stöpull, which contains directions for the best way to get there and they cross the bridge using that knowledge as a guide. When they reach the human world they find that everything there is very different from what they are used to and vöðlungar can easily get lost there. Pói and Míría are trapped by a family who thinks they are either elves or aliens and keeps them captive so that they can present them to the media. They encounter many strange things in the humans'' home, various strange contraptions and tools which fascinate and scare them. Míría is able to make herself fairly well understood, but even though vöðlungar can easily understand human language, humans have trouble understanding the vöðlungar''s language. It emerges that Allína, Míría''s mother, who has been missing for years, lives in the next town and when they finally manage to escape, she joins them. They are just barely able to cross back over the bridge and Allína and the children are met with an enthusiastic welcome on their return.

In the second book, Míría has moved with her mother to Dimmuborg (Dark City) and Kraki, Pói and their mother Vaðlína come and visit. Strange things are taking place in Dimmuborg, which just gets darker and darker with every passing day. The young vöðlungar find out that a light energy stone which is supposed to stay inside a tower in the city centre and light up the whole city has disappeared, and this has caused such darkness that the vöðlungar fall ill by the dozens and the city is quarantined. Kraki, Pói and Míría follow an old map which Kraki finds and find out what has happened and how they can fix it. With the help of Allína they once more set out on a journey to the human world and are able to recapture the stone as well as finding Míría''s dad, who had been missing for many years. They return, put the stone back in its place and save the kingdom of vöðlungar from darkness and horror.

The books about Dimma and Dimmuborg follow closer in the convention of the fantasy genre than Aðalsteinn Ásbergs''s earlier books. The children travel to another world, solve riddles and difficult tasks; and by joining forces they manage to save the world, all typical fantasy themes. New words are used for familiar things, cows are for instance called moos and babies are called borns. The style is very clear, and the device of renaming things sharpens the reader''s understanding and perception of a different world, by adding to the world''s foreignness.

Like fantasies generally do, Brúin yfir Dimmu and Ljósin í Dimmuborg have an underlying story, which is the protagonists'' search for place and purpose in life. In the beginning both Kraki and Míría are fairly unsure about their place in life and their future. Kraki expects that he will have to become a bridge guard like his father but has little interest in it, and Míría has no idea what the future holds, as both her parents are missing at the beginning of the story. After travelling into dangerous parts and fighting monsters and bad humans, they both discover what they want, and accept the roles they have been assigned in life.

Apart from poetry and children''s books, Aðalsteinn Ásberg has written a number of songs and lyrics. Amongst them are those found on the CD''s Berrössuð á tánum and Bullutröll which he wrote and published with his late wife, singer Anna Pálína Árnadóttir. Aðalsteinn wrote the lyrics to the songs, which are written in the style of rhymes and are both funny and lively. They are broken up by stories which engage the listeners, both young and old, with their mixture of humour and seriousness.

Clearly Aðalsteinn Ásberg Sigurðsson is a very versatile author, as his work ranges from poetry, children''s books, a novel, song lyrics and translations (although they have not been dealt with in this article). When his oeuvre is studied as a whole, one can see the author''s development through his works and the growing decisiveness and focus of his approach. As his writing so far encompasses a period of 25 years, it reflects the preoccupations of each era and he has easily managed to adopt the characteristics and preoccupations of the times.

© María Bjarkadóttir, 2004

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir

Awards

2023 - The National Broadcasting Service´s Writer´s Fund, for 2022

2018 - Prize for the project "Skáld í skólum" (Poets in schools) on occasion of the Icelandic Language Day. Aðalsteinn was the instigator of the project and accepted the prize on behalf of "Höfundarmiðstöð RSÍ"

2018 - Special recognition in a choir song competition on the occasion of Iceland's 100th year of sovereignty - for the poem "Þjóðvísa"

2010 - Prize from the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland's Foundation for Music

2005 - Award from the Alfred Andersson-Rysst fund (Norway)

2004 - Award from the "Síung" short play competition for the entre'acte "Lýsing"

2003 - Prize from the Author's Book Fund Reserve

2001 - Prize from the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland's Foundation for Music

1999 - IBBY Iceland Award: Berössuð á tánum (A CD with children´s songs)

1997 - The Icelandic Writer´s Fund

1994 - IBBY Iceland and Mál og menning: First prize in a short story competition for the story Ormagull

1990 - AB Publishing House Literature Competition: Dvergasteinn

1984 - The Icelandic Writer´s Fund

Nominations

1994 - The European Playwright Awards: Óvinir (Enemies)

Kvæðið um Krummaling (The Rhyme of the Raven)

Read more

Sumartungl (Summer Moon)

Read more

Dimmubókin (The Book of Dimma)

Read more

Ljóð í leiðinni: skáld um Reykjavík (Poetry to Go: Poets on Reykjavík)

Read more

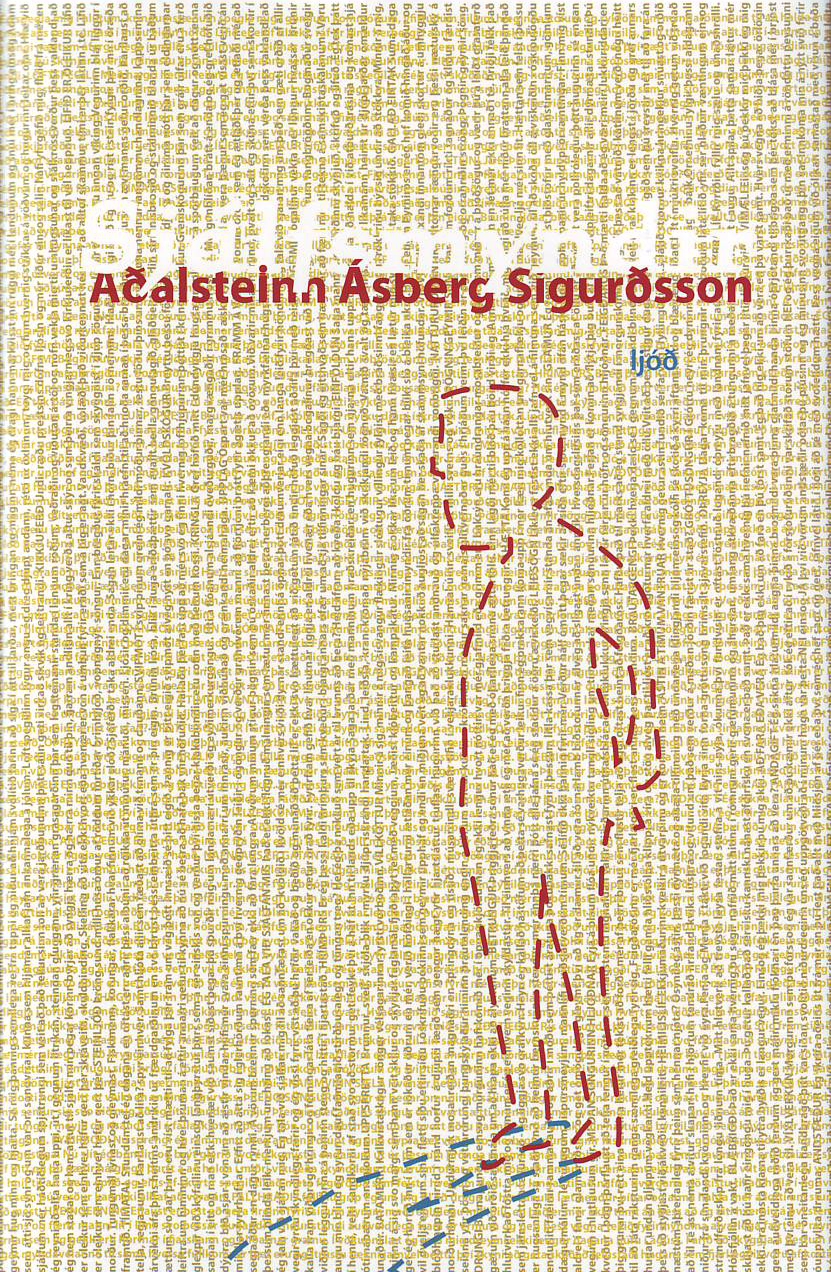

Sjálfsmyndir (Self Portraits)

Read more

Dvärgstenen

Read more

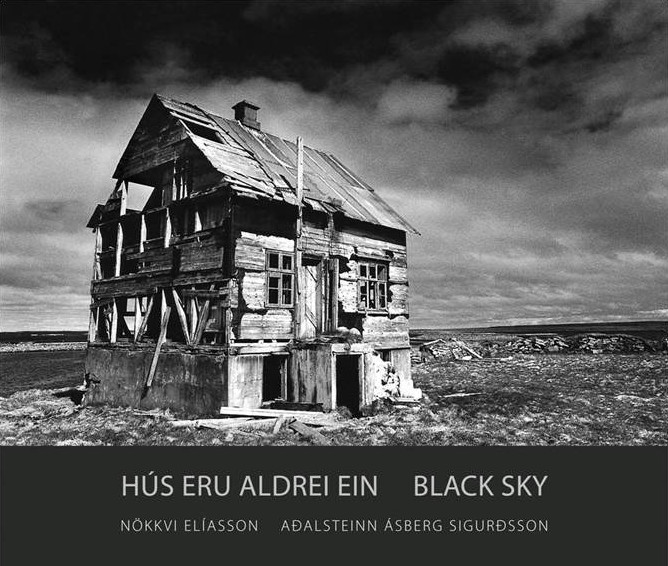

Hús eru aldrei ein / Black Sky

Read more

Black Sky / Hús eru aldrei ein

Read more

Segðu mér og segðu... (Tell Me and Tell Me...)

Read more

Rummungur ræningi (Der Räuber Hotzenplotz)

Read more

Heimferðir (Journeys Home)

Read more

Nýsnævi: ljóðaþýðingar (Virgin Snow: Translated Poetry)

Read more

Náttúruleg skáldsaga (A Natural Novel)

Read more

Hjaltlandsljóð

Read more

Beinhvít ljóð (Poems White as Bone)

Read more

Birtan í húminu (The Light in the Dusk)

Read more[Two poems]

Read more

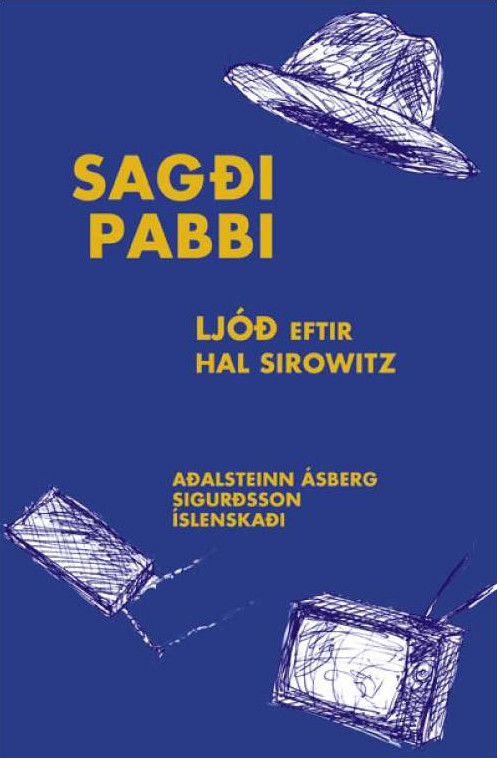

Sagði pabbi (Father Said)

Read more