Bio

Didda was born in Selfoss on November 29, 1964. After two weeks of living there, she moved to Reykjavík where she grew up. She tried out a number of elementary schools in the capital and then she went to the secondary school in Selfoss and later in Reykjavík. From 1987 – 1989 Didda studied at Cordwainers Technical College in London and graduated as a handbag- and purse maker, the only one to hold this diploma in Iceland.

In the eightees, Didda wrote a number of lyrics for Icelandic bands. The best known one is without doubt the lyric "Ó Reykjavík, ó Reykjavík", perfomed by the punk band Vonbrigði. Her first book, the poetry collection Lastafans og lausar skrúfur (Abounded Vices and Loose Screws) was published in 1995, followed by novels. She played one of the leading roles in the film Stormy Weather by French/Icelandic director Sólveig Anspach which premiered in Cannes in 2003. Didda received the Icelandic Edda award as the best actress of the year for her role in the movie.

Didda has done a number of jobs on the side of her writing career.

Author photo: Reykjavík Museum of Photography.

About the Author

On the works of Didda

In 1995 Didda published a book of poetry entitled Lastafans og lausar skrúfur [A gathering of sins and loose screws] that aroused some interest. The book is a collection of unstructured poetry and prose put forward in an autobiographical style. The following poem is an example of many of the books main characteristics:

Byrjun

Ég stoppaði einu sinni mann á Njálsgötunni og

við vorum bæði blindfull, og af því að hann var

svo lágvaxinn þá skipaði ég honum að ríða mér,

standandi upp við vegg. Og hann var til í tuskið,

stóð þarna lítill og boginn og hjólbeinóttur og ég

á einhvern veginn bara beint ofan á ennið á honum.

Svellbunkarnir sindruðu í stjörnuskininu og það

var svo dásamlega íslenskt að finna frostið narta í

ber lærin. Og svo fyrir kraftaverk eitt fékk hann

það og ég ýtti honum frá mér, hysjaði upp um mig

buxurnar og sagði bless.

Þetta var sá þriðji þetta kvöld og mér leið eins og

ég væri rétt að byrja.[Beginning

Once I stopped a man on Njálsgata and

we were both very drunk, and because he was

not very tall I ordered him to fuck me,

leaning up against a wall. And he was game,

stood there small and bent and bowlegged and I

somehow could only see directly down on his forehead.

Icy patches glimmered in the starlight and it

was so wonderfully Icelandic to feel the frost nibble at

the naked thighs. And then by some miracle he

came and I pushed him away, hoisted my

trousers and said good-bye.

He was the third one that evening and I felt as if

I was just getting started.]

The poetic I does not go easy on herself nor does she shirk from describing actions and experiences that some might find unseemly.

It is not unusual to find anal sex, the use of dope, prostitution and rape as the subject matter of the book. The book focuses generally, on a lifestyle, culture and the experiences that are not a part of the lives of “normal people”. This is not a case of ploughing the same rut as the Icelandic “poets laureate” of yore or tackling the literary traditions in an obvious way but there is first and foremost an effort made to show raw images of unenviable experiences (true or fictitious). It is by no means an exaggeration that the narrative is often quite dramatic. The main characteristic of the style is however the sharp sense of humour that mixes in with the painful experience. It is quite possible that the poem quoted earlier will cause a bitter smile to play upon the lips of the reader. Although it is not particularly a laughing matter that the woman is in such a bad way that she roams the streets and drops her trousers for anybody. The fact that the man''s shortness and the absurdity of the situation are highlighted draw the attention away from the sadness and accent the comic without lessening the power of the poem. The focus is mainly on the ridiculous but the fleeting presence of the extraordinary can also be detected. The poetic I also describes, in a lyric way how the “Icy patches glimmered in the moonlight”; a lot of attention is given to the surroundings while the real subject matter of the poem is quite different and more melancholy. This style could be compared to a reverse romantic irony, the driving force of the poem is the irony that later is matched by a rather sad reality.

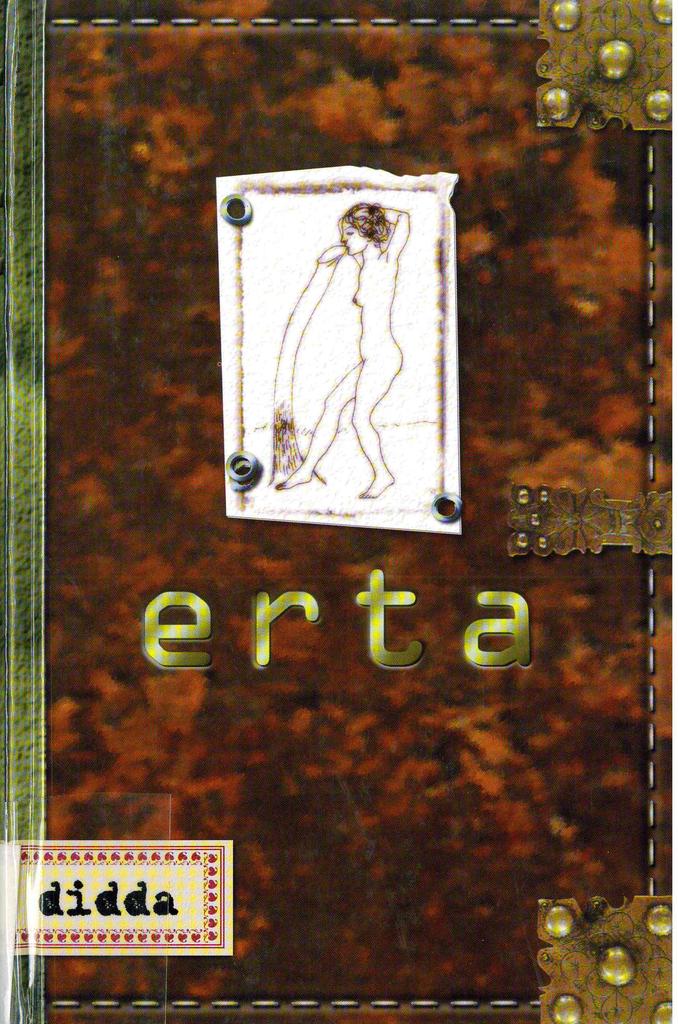

Irony plays this sort of balancing game with cold reality throughout the entire book. As a result the pain does not get sentimental and the pornography does not become pretentious. The book has a fresh sense of reality and manages to convey things that more polished methods would not necessarily have achieved. The poems are raw and unpolished both in subject matter and outer appearance. If one of Didda’s goals is to “provoke the reader” it can be said that she manages to do so first and foremost by having a sense of humour when it comes to her subject matters. This mixture of humour and stark coldness is something that characterises her whole body of work. In Ertu “A story in the form of a diary”, Didda continues much in the same vein.

miðvikudagur

dreymdi að verið væri að nauðga mér. allir nauðgararnir eru frægir grínarar svo að ég hló og hló allan tímann. hlýtur að vera ömurlegt að vera aldrei tekin alvarlega. (15)

[Wednesday

dreamt that I was being raped. all the rapists are famous comedians so I laughed during the whole thing. must be intolerable never to be taken seriously. (15)]

Like the poetic I in Lastafans og lausar skrúfur Erta goes through many unpalatable things without really taking them to heart. The above example shows how the effect of comedy is more powerful than tragedy, both in the mind of the main character telling the story and in the mind of the reader. Erta is more impressed by the comics and their comedy than the fact that they are raping her. It is only a dream, and so are quite possibly many other things we hear of in the book, but that does not diminish it as an example of the inner world of the character. In the two novels, Erta and Gullið í höfðinu (The Gold in the Head) half the narrative cavorts in the minds of the main characters and it is difficult to see the difference between their imaginations and reality. Even if “known surroundings give the story the flavour of realism” as the quote on the dust jacket says, the diary of Erta is more a testimony of her mindset and fantasies rather than real events. The following example shows this mindset pretty well and shows that it is most likely formed by anything but reality:

tvær löggur, mótorhjólalöggur í búningum og með hjálma. sólgleraugu. stórir, sterklegir, með leðurhanska. taka mig. annar aftan frá á meðan hinn sleikir á mér snípinn og ég er með stórt tippið á honum uppí mér.

byggingaverkamenn, sement á vinnuhönskunum, rafsuðulykt, olía, ryk, berir að ofan, einn er á hækjum sér og étur mig, skeggbroddar, stinga innan lærin, ég stend og sýg þann sem hangir á stillansanum. (48)[two policemen, motorcycle riders in their costumes with helmets. sunglasses. big, strong, wearing leather gloves. take me. one from behind and at the same time the other licks my clitoris and I have his big dick in my mouth.

building constructors, cement on work gloves, the smell of welding, oil, dust, topless, one on his haunches and eats me, stubble, prick the inside of thighs, I stand and suck the one hanging from the scaffolding. (48)]

There is no mention of whether this is a fantasy or a nightmare. The description sounds like it has been lifted directly from a hardcore pornographic magazine and is most likely a figment of Erta’s mind rather than one of her actual experiences. On the other hand one wonders why Erta repeatedly describes such circumstances in her book. Is she a pervert, schizophrenic or a “normal person” with a risqué sense of humour? We can not take for granted that any of the things that she describes have really “happened” but still they seem to happen to her constantly, the same thoughts, fantasies and her boldness and fears blend in with reality and thus she portrays her own life. At one point in the diary Erta says: ”It just does not do to tip-toe through life with ones own life in one heap in ones head. not unless life is a sort of train wreck that people have to get through without any trauma counselling.” (22)

It can be stated that Erta’s life is a sort of train wreck that she carries around in her head, and that writing the diary is the counselling that she is self administering. In the book her life is portrayed as a very chaotic one, from the ruins she picks out images of the wreck and mixes them with things that might have been, were perhaps, or are going to take place in the future. The diary does not give an account of Erta’s life, but rather the mess in her head. To escape from the chaos she seeks comfort in the physical and spends her days concentrating on her genitals.

og sólin vermir á mér bakið og ég nýrökuð að neðan og hef verið að hlusta á diamöndu galás í tvo daga. […] ólíkt betri tilfinning að vera rökuð að neðan heldur en undir höndunum. og eitthvað svo prakkaralegt að sitja eða standa eða ganga eða hvað sem er, tala við fólk, horfa á fólk, brosa, kinka kolli, hvað sem er, með rakaða mjúka nýja píku. setur einhvern veginn daginn og veröldina í nýjan gír. (23)

[and the sun warms my back and I have just shaved down below and have been listening to diamanda galás for two days. [...] it feels much nicer to shave down below than under the arms. and I feel like such a prankster, sitting down or walking or whatever, talking to people, looking at people, smiling, nodding, whatever, with a shaved soft new pussy. somehow it puts the day and the world into a different gear. (23)]

The way Erta senses her surroundings does not seem to be formed by their nuances but rather by how she herself feels. She gains a completely new vision of life by shaving her genitals, but other days are grey and dull, the people disgusting and the world full of hatred. This highly centralised view of life seems to point to the fact that Erta is no ordinary everyday person, and possibly the inner workings of her soul and body askew compared with most people. The accentuation on the physical and carnal and its effect on the spiritual directs us somewhat into Didda’s next book, the novel Gullið í höfðinu [The Gold in the Head ], where this is the main subject matter.

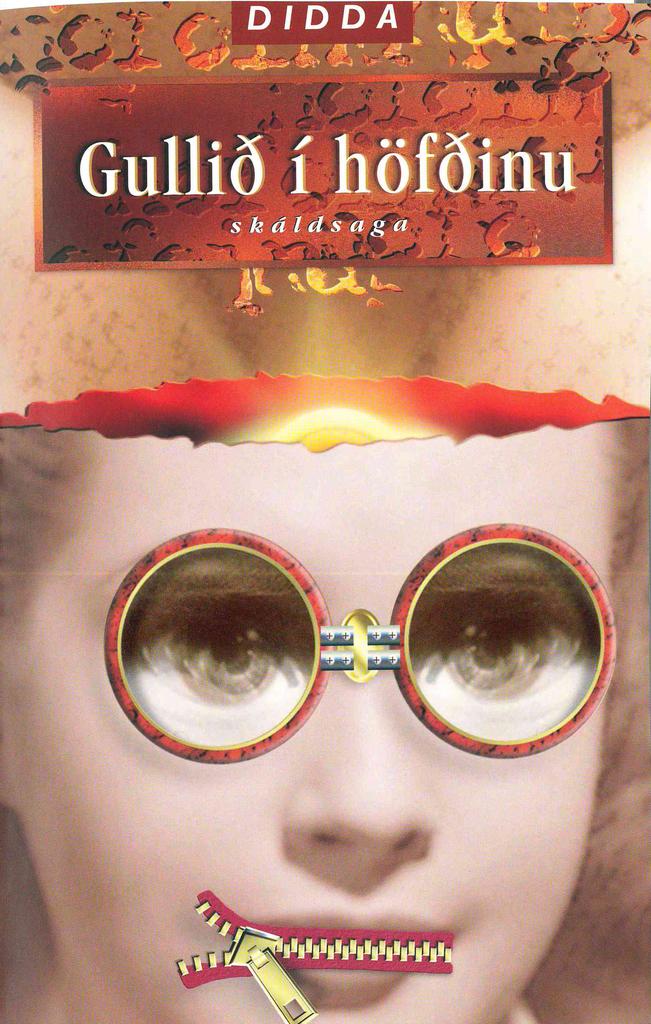

Gullið í Höfðinu was published in 1999. In that book a young mentally ill woman gives an account of some of the various not so nice events and experiences of her life, all the way from her lone youth to her lonesome time as a grown up. In this book as in the others, there is no squeamishness when it comes to describing the experiences of the characters. Katla, like Erta, seems to have seen a thing or two and is not easily shocked – on the surface of things anyway. Her total lack of sentimentality and her acknowledgement of certain strange circumstances soon make one suspect that she is not totally happy with her lot. What seems like a game to her is probably a tragedy, and her calm demeanour and the objective narrative she uses to portray a variety of crude scenes is hardly to be trusted. This narrative method is slightly problematic. Either Katla is making everything up or is quoting real events that have influenced her to such an extent that she recounts them as if they where normal situations. When it comes to the believability of the narrator we have here the same situation as in Erta. Without thinking one wonders whether she is re-shaping the weird story of her life or has even changed all the circumstances completely and formed them by her view of life.

Katla is a resident of a mental institution and it is easy to draw the conclusion that she is imagining things that have never taken place. An example is he description of how the mother of her friend abused her when she was a child. But one can also imagine that the mentally ill person is the one speaking the truth, as can be seen in the plays of Shakespeare. I.e. that Katla is not really mentally ill but has fallen pray to dubious and terrible situations that finally drive her to silence and shut her off in her own world. The narrators in Didda’s stories are particularly devious when it comes to this. You cannot accept their narrative without doubt but you cannot write them off as crazy. It transpires that Katla’s experiences where quite serious, the lurid descriptions are based on something and they are not made solely to shock. As the story unfolds it becomes clear that Katla was abused, if not by the lesbian mother of her friend then by her uncle. Describing sexually explicit scenes obsesses Katla, physical violence and pornography can be understood as her reaction to her own experiences. Outwardly this manifests itself as numbness and lack of compassion towards life, but the struggle and fear still live within her. When at the end of the book she discovers her human connections to her own experiences her barriers come down, she regains speech and starts telling her tale.

This might be one understanding of the book. It is at least clear that Katla’s psychological problems are closely connected to her body. When the problems start to emerge, eggs and chicken for instance obsess her. Her craziness has almost always some physical connection and the symptoms are mostly physical. She stops talking, mostly she is quiet but she also attacks a female guard and rapes her. She explains this herself when she says that “she falls for women” but the descriptions of her sexual experiences do not indicate that this is any normal homosexual experience but rather something that ties in with her state of mind, in one way or another. Katla’s descriptions of other patients are always connected to some sort of physical defects. One of the women has been cutting herself since she was fourteen and another is an unfulfilled orgasm addict that everyone is free to use. “She seemed to be the most care free person I had ever met, and to the same extent perfectly dead because of the orgasms that she seemed to be addicted to, and she seemed to be both untouchable and at the same time open to everyone.” (98) Just like Katla’s descriptions of other patients are almost always of women and their physical appearances, then so are also the descriptions of bodies and sex almost always connected to death. “...I knew why people die a little when they fuck [...] knew it was dangerous to have an orgasm, more than dangerous, it is half a death.” (75) Katla also imagines that the staff at the hospital will save the female guard that she rapes “before she dies a little.” (89)

This constant connection between sex and death boosts the view that Katla was really raped and that the book, in part at least, is about the victims of sexual violence. When she witnesses the rape of a young girl at a school party (page 58-63), Katla’s reactions are some sort of a deep lack of compassion that seems to show some real understanding of the matter. In Erta, this lack of compassion manifests itself in a very black sense of humour: “There once was a drag queen in New York that took rat poison, slashed her wrists and threw herself out of a third floor window, didn’t die, but was trying to say something.” (42) It would perhaps be better to say that she identifies with, rather than has no compassion for these people, the characters’ dull reactions to dramatic situations show that they are an every day occurrence. This way Katla, Erta and the author of the books manage to discuss matters that are in a way taboo, without over dramatising or fall prey to sentimentalism.

Didda’s writing has its roots in Punk Rock. Punk Rock is probably more akin with a way of life or a certain kind of philosophy, more so than simply a music genre, even if that may have been the beginning of the whole idea as an art form. The Filth and the Fury could have been the title of an older literary genre and ideology, like the one formed by the French poet Arthur Rimbaud just over a hundred years before the Sex Pistols forged the way for Punk Rock. Didda’s glorification of ugliness (or is it perhaps the beauty of ugliness?) is something she has in common with both Rimbaud and Sid Vicious. Also the provocation of the standard moral code that does not have room for pornography, perversions and abnormal behaviour and the self-destructive impulse described by their art or simply performed by it. In Rimbaude’s case this philosophy was home made, it came from his extensive reading of bourgeois and revolutionary writings. And that formed in him a dislike for the affluence and got him to roll in the dirt, to acquire himself some experience of the muck, “to try on himself all the different kinds of; love, intoxication and madness.” Rimbaud’s Punk Rock was totally romantic. I am not entirely sure if the same goes for Didda. Rimbaud’s poetry is when all is said and done very “intellectual” in contrast with Didda’s writing which is raw, erratic, chaotic and full of unprocessed pornography. When reading her work, you get the feeling that the author has deliberately sought out distasteful experiences in order to be able to write anti bourgeois books and to provoke the uptight people of this world. There are no thoughts on what is worth putting in a story, what the lot and role of the author is. Didda’s Punk Rock, if we can call it that is, in other words, is quite devoid of awareness and as a result the grotesque and the emphasis on disgusting things does not become absurd but feel very real and that comes across to the reader. It is her book of poetry that is her most personal work and closest to her own experiences. That is if you can trust the text on the dust jacket; the poems are “no lies but fragments of truth and images from her life.”

Literary theory has for the past decades tried to rob the authors of their work and ism after ism has made it its mission to prove that literature lives and springs from almost anything except the heart and imagination of the author. Here it is enough to mention reception theory, deconstruction and new historicism, many more fall into this category due to their similarity. The declaration on the cover of Lastafans og lausar skrúfur that the contents of the book tackles the real experiences of the author must kill all speculations of it being otherwise, even though it could possibly be fiction itself. Didda’s two later books engage in a very similar sphere of experiences and it is obvious for a critic, who refuses to dump all the autobiographical approaches, to declare that Didda’s writings are “inherently” grotesque or Punk Rock. Didda does not hold many things sacred. Her approach to the subject matter and the methods used to convey it are probably too similar for me to say that the provocation in the work is expressed in a manifold way. The same refrains crop up time and again and readers who are not total prudes get used to her unpolished style pretty quickly. Those who have read beat poetry, pornographic magazines and schizophrenic literature, listened to punk rock and felt like outsiders, been filled with anger towards the world and laughed at it at the same time, they will understand that Didda’s influences come from all over. They will also suspect strongly that behind the “mockery and the sorrow” there hides a sincerity that belongs to the author herself. Now the question is whether Didda will give up the punk rock, channel her sincerity into paths that lie towards a reconciliation with life and even receive an honour from the President (Fálkaorðan) for her work for the good of Icelandic literature. Maybe not, it is more likely that she will continue to be a non-mainstream author aiming to convey experiences that hopefully most of us manage to escape. It is possible to look upon her work as quite humorous, and one can find in them a lot of humour and mockery. But it is also possible to take it very seriously and reflect that we are all “normal people” that simply observe life with a varying degree of a “distorted view”. That the standards are formed by the view of the masses but are not an unbreakable law or eternal truth. It is possible that Didda the poet and her fictional characters show us these standards mostly by striving against them and to try to find something true where there is so much false and broken.

Sölvi Björn Sigurðsson, 2003.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 453

Poems in The Other Side of Landscape

Read morePoems in Wortlaut Island

Read more

Gullið í höfðinu (The Gold in the Head)

Read moreDie Farben unserer Visagen im Winter 1 Gedichte & 2 Texte

Read more

Erta

Read moreLastafans og lausar skrúfur (A Gathering of Sins and Loose Screws)

Read moreDagbók: Didda (Diary; Didda)

Read more