Bio

Gerdur Kristný was born on June 10, 1970 and brought up in Reykjavík. She graduated in French and comparative literature from the University of Iceland in 1992. Her B.A. dissertation was on Baudelaire's Les fleurs du mal. After a course in media studies at the University of Iceland from 1992-1993 she trained at Denmark's Radio TV. She was editor of the magazine Mannlíf from 1998 - 2004, but is now a full time writer.

Gerður Kristný has published poetry books, short stories, novels and books for children, as well as a book about the Westman Islands Festival in 2002 and the biography Myndin af pabba - saga Thelmu (A Portrait of Dad - Thelma's Story). This true story of Thelma and her sisters growing up in the 60's and 70's with their sexually abusive father shocked readers in Iceland and Gerður received The Icelandic Journalism Award in 2005 for the book.

Other awards for her work include The Children's Choice Book Prize in 2003 for her book Marta Smarta (Smart Marta), The Halldór Laxness Literary Award in 2004 for her novel Bátur með segli og allt (A Boat With a Sail and All) and The West-Nordic Children's Literature Prize in 2010 for the novel Garðurinn (The Garden). Gerður's collection of poetry, Höggstaður (Soft Spot) was nominated for The Icelandic Literature Prize in 2007 and she then won the prize in 2010 for her poetry book Blóðhófnir (Blood Hoof), which is based on the myth about Freyr and the poet's namesake Gerður Gymisdóttir from the Eddic poem Skírnismál. In 2021 Gerður Kristný won the Women's Literary Award, Fjöruverðlaunin, for her children's book Iðunn og afi pönk. In 2024 she was awarded a Norwegian literature price named after author Alfred Anderson-Ryssts.

Gerður Kristný's poetry and short stories have been included in school textbooks at the elementary- and secondary level, as well as in anthologies and periodicals published in Iceland and abroad. The biography Myndin af pabba was published in Sweden in 2008 as Bilden av pabba and some of her poetry has been translated as well, to English and other languages.

From the Author

From Gerður Kristný

A little while ago I met an old girlfriend of mine from school who reminded me that the first time she met me, when I was 16, I had introduced myself with the words: "Hi, my name's Gerður and I'm a poet."

I was still a child when I decided to be a poet and a writer. From the start I thought it was obvious that I could write books after having the good fortune to enjoy outstanding children's books which were written with such artistry that anyone would think these stories had always existed. Naturally the twins Guðrún Helgadóttir and Astrid Lindgren were my favourites, and when I grew older the Lotta and Putzi books took over. Reading good children's literature was the key to my interest in books. Without them it would never have been kindled.

Instead of sitting with The Sagas of the Kings of Norway under my desk at the age of six like Thor Vilhjálmsson, I read books for children and young people well into my youth. I was 16 when I finally started looking at Selma Lagerlöf and Halldór Laxness. To tell the truth I could even make a list of all the books I've read since I was 16, since I've written down the name of every one. Looking over the first year of that obsession with documentation, it emerges that I was reading then about teenagers snogging in Andrés Indriðason's books, in between vengeance killings in Njál's Saga and getting Out of Key with Jökull Jakobsson.

When I started writing poetry I thought it was obvious to show people my poems. My mother and teacher were singled out and thought they were "just great." So I saw no reason to hide them away any more. My classmates also thought it was quite natural for me to write poems just as one girl was good at ballet and one boy had a horse. And there were others who could write. At lunchbreak when we were 12 and 13, one of the boys used to read out from a story he had written about toilet-imps and their attempts to gain world domination. All his classmates were characters in the story, and we took a voracious delight in this entertainment and howled with laughter when our names came up. The boy's career in writing did not go beyond that, because at an early age he fell under the enchanting spell of actuarial mathematics.

I do not need to go into any more detail about my progress in high school since it seemed so perfectly natural to me that everyone knew I wrote poetry. And so what? Other people saw no reason to hide the fact that they were in the choir or drama club. In fact I kept a low profile for the first winter , but in the spring I published a poem in the school magazine. I didn't dare to use my own name, however, so I published it under a pseudonym. But unfortunately it turned out that there was a girl at school who had the very name I had used. Judging from her angry reaction she clearly regarded this as a dubious honour because in the next issue she kindly asked the unknown poet to find another name to hide behind. Since then I've used my own name.

When I was 23 I started to wonder about getting published. A man whose judgement I value encouraged me to do so and I tumbled into Mál og menning publishing house with a handful of poems. My first book amounts to only 20 poems. It's so slim that I don't receive any royalties when it's borrowed from the City Library. A book has to be 36 pages to be qualified a serious book. Perhaps I'm not a serious writer either. At least, one man felt compelled to approach me and tell me I wasn't a serious artist because I work as a journalist. Yet I have a letter from him in which he heaps praise on my first book of verse.

I didn't reply to him, since I don't think it matters whether people write their books at lunchtime or before dawn, wearing a shop overall or nothing but a pair of woolly socks, listening to an Italian aria or the whirring of the washing machine, just as long as they take pains while writing. That is what it's all about, taking pains. Then there's no problem about regarding yourself as a poet.

Some day later, hopefully, someone else will regard you as a poet – and a painstaking one.

Gerður Kristný, 2001.

Translated by Bernard Scudder.

About the Author

Who Killed Snow White?: On the poetry and fiction of Gerður Kristný

The marker-posts bear

witness to your craftsmanship

what remains of the journey

I read from the map myself

while I am steering

The taming of the poet

The opening lines of the road poem “Journey” from Launkofi (Hideaway, 2000) are typical of Gerður Kristný’s work. They reveal solitude, the quest for strong self-awareness and a yearning for independence. A woman seeks to release herself from the shackles that society has imposed on her and rejects her conventional role, but her dissidence is often doomed to failure.

Gerður Kristný has never flinched from defining herself as a feminist. While other poetesses tend to deny all connection with the women’s rights movement, Gerður has championed its ideals in her works and columns, in newspaper articles and television debates. Her strong views have attracted attention and she is regarded as a scathing critic of male power. Gerður’s image in the media reflects here attitudes and has had a visible impact on the reception given to her works, as is often the case among female authors who challenge the tradition. In this respect she occupies a unique place on the Icelandic literary scene. Evidence can be widely seen in public coverage of Gerður Kristný, whether it be in book reviews, interviews or the works of contemporary authors.

Media coverage of Gerður Kristný clearly reveals the need to dramatize her as a hard-headed women’s libber, as shown by Páll Ásgeir Ásgeirsson’s interview with her published in DV newspaper in November 2000. There, Gerður “glares” at the journalist, they “joust across the table” and even the weather reinforces the atmosphere, as they sit “in foul-tempered morning rain”. Incidentally, in her 1999 article “Not dead ? just forgotten”, Gerður Kristný criticizes Páll Ásgeir Ásgeirsson for excluding female writers in his coverage of Icelandic detective stories. Thus Gerður’s image as a “strong” woman who poses a threat to male values indirectly comes across in the journalist’s imagery. This image has become so deeply-rooted in Icelandic society that Gerður, who has only just turned thirty, has been identified as the prototype for the female journalist Gyða Dís in Hallgrímur Helgason’s play Skáldanótt (Poetic Night) and as the female journalist in Ólafur Haukur Símonarson’s play Vitleysingarnir (The Idiots). Páll Ásgeir Ásgeirsson discusses this point in his interview. Hallgrímur Helgason’s play Skáldanótt was performed at Reykjavík City Theatre in winter 2000-1 and Vitleysingjarnir by Ólafur Haukur Símonarson at Hafnarfjörður Theatre the same season. This is surely unexampled for such a young author.

Given how visible Gerður’s image is, critics have had trouble in approaching her work on independent assumptions. Headlines about her suggest a somewhat one-sided discussion of her work. She is called a “Maestro of bitchiness”, reviews of her books bear titles such as “Cold as Steel” and “Ode to Strong Women”, and sometimes Gerður’s own words are taken out of context and used as headlines for interviews: “That Icelandic repulsive humour”. Nor do critics explore new territory in describing her writing. Terms such as irony, sarcasm or mockery are eagerly seized upon to dismiss her style in an instant. Instead of using concepts to expand the meaning of her texts, they are all branded with the same mark. This restricts dialogue about the works and has a formative influence on their general reception.

“When I die”

“The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetic subject in the world,” said Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), referring to a centuries-old tradition in literature and art. Women writers often write themselves into this tradition, but tend to elaborate upon it in a different way. In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) contemplates the tragic fate of an imaginary sister of Shakespeare, who has the same literary gifts as he does. The sister is not allowed to develop her talents and runs away from home in search of opportunities. Her short life ends in suicide. With her story about Shakespeare’s sister Woolf created a new literary motif which prompted scholar Elisabeth Bronfen to paraphrase Poe and make the most poetic subject of female writers the death of a woman with poetic gifts. (Elisabeth Bronfen: Over Her Dead Body: Death, feminity and the aesthetic. New York: Routledge, 1992, p. 404). Woolf says of Shakespeare’s sister: “She lives in you and in me [?] for great poets do not die”. Shakespeare’s sister thereby symbolizes the creative options available to women when they receive the chance to develop their gifts.

In Hideaway Gerður is preoccupied with death in all its manifestations. One poem is occasioned by Sylvia Plath’s suicide by gassing herself in February 1963. In it, Gerður aligns herself with the female tradition of writing about the untimely deaths of poetesses. In Gerður’s poem “Sylvia Plath”, the witch has gained the upper hand:

Before she wheedles her way

under your ribcage

and huddles up against

your heart

open up the oven door

and push her inside

The reference is to the folktale of Hansel and Gretchen, but here the witch and the female writer merge into one.

Gerður’s short story collection Eitruð epli (Poisoned Apples) implies a similar folktale link; in that case, the female writer gives poisoned apples to her readers. Likewise, female poets commonly write of their imagined deaths, as Gerður does in her “God":

When I die

you shall whittle

biting frost

from my teeth

fashion whistles

from my bones

and play those howling pipes in the wind

Death, in this poem, is active and alive, even a creative force, though tragic too. There is no yearning for death in Gerður’s poetry, unlike the works of many poetesses who are preoccupied with death. While drawing upon the tradition, Gerður also elaborates upon it in her own independent way. Hideaway also contains a memorial poem to a girlfriend, “Patball”, and “Bergþóra”, which examines the death of Bergþóra [who refuses to leave her husband when he goes to meet his death by burning] in Njál’s Saga from a new, feminist perspective.

The poems in Hideaway draw upon the Christian religion as well as linking up with the literary heritage, including folktales and romances. The opening poem, “Cheers” is in many ways typical of the entire book and presents two versions of the Creation, Christian and poetic, alluding to “The Cup” by Jóhann Sigurjónsson and to Genesis. However, it could be claimed that biblical imagery yields to pagan in “Wingspan”, with its image of a god which in many respects is reminiscent of the Greek myth of Leda and the swan:

In a fraction of a second

God throws on

his guise of weather

and sinks you in

his wide-reaching wingspan

“Greetings from Ararat” alludes to Noah’s ark running aground on Mt. Ararat (Genesis 8:4). The ark of the speaker of the poem, however, is made of paper (Icelandic örk means both “ark” and “ream") and the oars are quill pens: “I provide the oars myself/whittle them from /the feathers of birds”. Other poems with biblical allusions include “Love Poem”, which deals with Eve’s creation from Adam’s rib: “one of them/is yours”.

Hideaway also contains poems that Gerður associates with Icelandic folktales and the style of the sagas. She writes about ghosts and revenants in “Thanks”, “Depths of the Mind” and “Franklin”, while other poems are in direct continuation of the prevailing motifs and themes in her first book of verse, Ísfrétt (Ice Report, 1994).

In Ice Report, Gerður draws on the imagery of pagan times, including the Viking Age, the sagas and Greek mythology. Above all, the poems are connected with the theme of love. But many of them are chilly in atmosphere, as best illustrated by the images of pagan funeral customs. The speaker of “Vengeance” kills her love, carries it outside and buries it in the “dead earth”. Helpless love has died of exposure and been buried in unsanctified ground far from the realm of humankind. Similar symbolism may be seen in the love poem “With fire” with its image of a chieftain’s ship-burial and cremation. The slave in “Loving regards” recalls the Tollund man, who was exhumed in a well-preserved state from a peat bog in Jutland with a noose around his neck:

The words dig dark holes

where my eyes once sat

winds play across your lips

groping to feel the pulse

of the slave to be interred

with his master

The slave follows his master to be buried in the same grave. The speaker of the poem is the submissive, rightless slave of the person he loves.

Both Gerður’s volumes of poetry contain reworkings of ancient literature from female perspectives. Bergþóra’s tragedy is retold in Hideaway while Ice Report focuses on Hallgerður Long-Breeches in “Hallgerður’s Verses”. “To Skírnir” refers to the Eddic Poem of Skírnir which recounts how Skírnir used threats to force the mythical figure Gerður into a lovers’ tryst with the god Freyr. As the title of the poem implies, it is Gerður (Kristný) who addresses Skírnir. All these poems draw attention to the powerless status of the women in them. The eponymous heroine of “Medusa”, however, is endowed with great force, as one of the Gorgons who can turn men to stone by looking them in the eye.

Frost, winter, ice and fire are dominant images in Gerður’s first book of poetry, as illustrated for example by the love poems “Ice Report” and “Rock”. Yet the relationships in these poems are not characterized by the intense coldness that can be discerned in the funeral poems. Rather, they involve the interaction of heat and cold, and fiery love melts nature’s covering of ice. In Ice Report the setting is pagan, nature images predominate and love is important. In Hideaway a new age has dawned, the speaker of the poems has become more Christian and the themes are different: death and the world beyond have become part of life.

Escape for women

The flaneur has long been a prominent literary figure. It is associated with Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), who is thought to have devised the notion of the flaneur in the modern metropolis, more often than not an artist who roams through the bustling city contemplatively watching his surroundings. Far from the security of the home he submits to the command of the unknown. Because of the attraction that the modern city exerts upon him, he has been associated with modernism. Feminists point out that the female version, the flaneuse, first appeared in the twentieth century when women began roaming the streets shopping; before then, it was mainly female artists and prostitutes who went out on their own.

As pointed out at the beginning of this article, Gerður Kristný’s female characters yearn to be independent and go their own way in life. The need for freedom manifests itself clearly in Tinna, the main character of the novel Regnbogi í póstinum (A Rainbow in the Post, 1996). The story is set in Reykjavík, in Paris where Tinna looks after children and looks around, and in Copenhagen. Tinna’s identity is interlinked with the flaneur concept. The text suggests that she longs to be like the authors Halldór Laxness and Pétur Gunnarsson, who lived and wrote in Copenhagen for a while. Tinna thinks about their travels, and by her flanerie seeks to acquire the artist’s experience.

As is customary with flaneurs, Tinna is far away from her home and does not even inform her parents when she goes to Copenhagen: “I said I was going to take the train to Madrid. I don’t know why I said Madrid. It just sounded better than going to Copenhagen” (13). Tinna is eager to associate herself with the life of the male flaneur that has read about in books, but has to make do with going “home” to Copenhagen rather than journeying by train to even more remote parts.

Despite her desire to be free and independent on her travels, Tinna’s thoughts often turn to her family, and in Copenhagen she goes to look at the apartment block where her father once lived:

I feel a weird feeling when I suddenly stand in front of the red apartment block where he once sat with his friends in the indispensable lotus position, listening to Cohen and having tea and oranges that came all the way from China. I’ve seen the building on faded photographs. I particularly remember my father on one of them, standing on the steps with Arnar beside him. (37)

Unlike the normal artist of the street, Tinna does not enjoy being free to go where she pleases. Yet instead of parading the way she feels inside, she is closed and sardonic and even gives a nonchalant impression. It is hinted that her visit to her mysterious uncle Arnar, who lives in Copenhagen, changes her identity. After Tinna sees how her family pretends that Arnar’s mental illness does not exist, she decides to stop her flanerie and go home.

Readers do not find out about Tinna’s emotional life, but a bell-cord which was a gift from her grandmother and contains photos of Tinna at different ages is a symbol showing that her journey is a quest for the self. Bells are common symbols in the Bildungsroman; suffice it to mention books as different as Gangvirkið [1955] by Ólafur Jóhann Sigurðsson, Behind the Scenes at the Museum [1995] by Kate Atkinson and The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman [1760] by Laurence Sterne. At the start of the story she cannot identify with any of the photographs on the cord:

The uppermost photo shows my current age. A short-haired woman wearing a pink dress is sitting beside the radio, talking on the phone [?] and I, who have always been able to point to some picture or another and say: “That’s what I’m like now”, no longer have any photo to point to. (5)

The description of Tinna towards the end of the story, when she is wearing a pink dress, talking on the phone to her mother and saying she wants to come home, resonates with the photo on the bell-cord on the first page of the book. And she thinks: “For an instant I feel reminiscent of some woman I know. I just can’t remember who”. (139). These words of Tinna’s may be the first sign that she has realized she is not the flaneuse she wanted to be.

Another lost flaneuse appears in the short story “Escape for Men” which was printed in the collection Poisoned Apples (Eitruð epli, 1998). The female character travels to the south of France with her boyfriend who leaves her because she thinks too much about an old boyfriend who lives there. The character does not want to be dependent on anyone and goes her own way, as stated shortly before her boyfriend leaves her:

On the third day I started wondering whether Paul was still living in the same place. I said I was going for a walk the next day to see whether I could find the house where his parents lived. Frikki said I could go without him. That was no news to me. There’d been no other option. (11)

The story deals with her roaming by day and by night, her journey to an unfamiliar town and her escape from the boyfriend who returns to her. As in A Rainbow in the Post, it depicts the type of female freedom that involves being able to travel from o e place to another virtually without interference. However, this freedom is limited, because the character does not seem to have anything else to do but roam around and go from one boyfriend to another.

Lost women recur throughout G rður Kristný’s work. An example is the bride in the stage work Bannað að blóta í brúðarkjól (No Swearing in Your Wedding Dress, 2000), who delivers a speech in front of the wedding guests only to discover at the end that she is in the wrong place. Her monologue reveals her deflated identity and insecurity about the love of the man she has just married. The bride is self-contradictory and the text suggests that she has been living in self-delusion for so long that she can no longer distinguish her real lot. The following passage appears twice in the play, creating an impression that it is the bride’s subconscious which is revealed here:

It is through pangs of conscience that people first become poets. That is why there are convicted murderers who claim never to have killed anyone even though their fingerprints have been found on the victim, and there are also people who say that the six million Jews who died during the war were not killed but beamed up into space by aliens, and last but not least there are boys from the Westman Islands who say they love a girl from the suburbs of Reykjavík. Who am I to forbid that?

The bride is a poet and her life is a huge lie that she tries to convince herself is true. Her story is really the tragedy of the woman who covers up the emptiness that consumes her from within.

What about Rue de Marianne?

Some women in Gerður Kristný’s short-story collection Poisoned Apples live monotonous lives and attempt, with varying degrees of success, to break out of them. Women have long had to counter the need to attend to their female duties, but as Virginia Woolf describes in her essay “Professions for Women” the fight against the Angel in the House is not an easy one. The Angel in the House is the female conscience incarnate.

When the Angel in the House disturbs Woolf while she is writing a review of a book by a man, it whispers into her ear: “Be sympathetic, be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the arts and wiles of our sex. Never let anybody guess that you have a mind of your own. Above all, be pure.” (Virginia Woolf: “Professions for Women”. Women and Writing [1942]. Ed: Michèle Barret. New York/London: Hartcourt Brace & Company, 1979, p. 59.) When Woolf saw that the angel was beginning to control her writing, she killed it. It haunted her, but eventually disappeared. This parable describes how women who want to write have to break out of the female role, difficult as that may prove for them.

In her stories, Gerður Kristný describes women in conflict with themselves and the society that forces them into submission. The female character in Poisoned Apples who comes closest to transforming her daily life and acquiring a strong identity is Maríanna in “Rue de Marianne”. She adopts a new lifestyle and starts writing after having captured a sex criminal and misogynist: “In the light of recent events I have decided to keep a detailed diary” (41). Maríanna’s enhanced identity is implied through her writing, and also the demand for a name: “I intend to follow through my wish to have the name of my street changed into something French. What about Rue de Marianne?” (49).

Another female character who uproots herself from her mundane existence is the main character in the sequence “Stories of a Sewing Circle”. Following her idea for an original emblem for the sewing circle, her life begins to change. She realizes that one of the members, Maja, is actually a man, and that she is attracted to her/him: “On the way I started thinking about Maja. I wouldn’t mind being able to spend more time alone with her. Preferably somewhere quiet and peaceful, somewhere far away from all other people, where no one could disturb us” (63). Now she can behave in accordance with her longings. In the story “Sun Sisters” her words come true, when she and Maja sail away together, just the two of them.

Other women in Poisoned Apples are less successful in their battles with the female role. The female character in “No Angel” is slapped around the face by a cementing worker for answering him back after she walked on a pavement that was not dry. Intending to take revenge, the young woman goes back to the place towards evening, lies down on the cement and makes angel’s wings in it. It freezes and she becomes transfixed in the cement in the form of an angel. It is possible to agree with Geir Svansson when he says in his review of the story: “She is an angel and always will be, whether she wants to be or not.” (See Geir Svansson: “Saumað að systrum”. (Sewing up the sisters) Morgunblaðið, Dec. 15, 1998, p. B3). Here we see a much more hopeless battle with the Angel in the House than that recounted by Woolf. Male authority stands unswayed even if individuals make minor shows of resistance.

Poisoned Apples contains a variety of allusions to the literary heritage. In “Sun sisters”, three girlfriends are turned into pigs while sunbathing on a Greek island. The main character and her girlfriend eat the other one. Here the reader has entered the territory of the enchantress Circe, daughter of the ancient Greek sun god, who metamorphosed Odysseus’ crew into pigs when they landed on her island. The final three stories in Poisoned Apples are comic horror stories describing and illustrating mutilation and violence. The beast within woman has awoken. Other tales of this kind include Angela Carter’s horror stories in The Bloody Chamber.

An examination of Gerður Kristný’s work clearly shows that her application of irony is not simple. In some cases it is used to suggestion emotions or a psychological state that cannot be expressed in words, thereby avoiding disconcerting sentimentality. Irony envelops the characters and shelters them from the eyes of prying readers. Behind the irony we gain glimpses of characters who differ from what might be expected on first impression.

In order for a single apple to provoke a war, kill a princess and exterminate humankind, someone needs to poison it. Was the witch perhaps a poet?

Alda Björk Valdimarsdóttir, 2001.

Translated by Bernard Scudder

Articles

Interviews

"Maintenant #5 - Gerður Kristný" An interview with Gerður Kristný.

The webzine 3:AM Magazine: http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/maintenant-5-ger%C3%B0ur-kristny/

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 455-456, 499

Awards

2024 - The Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Jarðljós. As the best poetry book of the year

2024 - A Norwegian literature price named after author Alfred Anderson-Ryssts

2023 - RÚV Writers' Fund

2023 - Fjöruverðlaunin - The Women's Literature Prize: Urta

2021 - Fjöruverðlaunin - The Women's Literature Prize: Iðunn & afi pönk

2020 - The Jónas Hallgrímsson Prize

2018 - The Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Sálumessa (Requiem). As the poetry book of the year

2010 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Blóðhófnir (Blood-Hoof)

2010 - The Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Blóðhófnir. As the best poetry book of the year

2010 - The West-Nordic Children’s Literature Prize: Garðurinn (The Garden)

2010 - The Guðmundur Böðvarsson Poetry Award

2008 - The Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Garðurinn. As the best children’s book of the year

2005 - The Icelandic Journalism Award: Myndin af pabba. Saga Thelmu (The Picture of Dad: Thelma’s Story)

2005 - The Icelandic Bookseller’s Award: Myndin af pabba. Saga Thelmu (The Picture of Dad: Thelma’s Story). As the best biography of the year

2004 - The Halldór Laxness Literature Prize: Bátur með segli og allt (A Boat with a Sail and All)

2003 - Bókaverðlaun barnanna (The Children’s Choice Book Prize): Marta Smarta (Smart Marta)

1998 - Third prize in Vikan magazine short story contest

1992 - First prize in a TV culture poetry competition, the National Broadcasting Service

1987 - Third prize in Þjóðviljinn newspaper poetry competition

1986 - First prize in the National Broadcasting Service short story competition

Nominations

2024 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Jarðljós (Earthlight)

2024 - The Reykjavík Children‘s Book Awards: Translation of Múmínálfarnir og hafshljómsveitin by Cecilia Davidsson

2019 - The May Star: Sálumessa

2018 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Sálumessa

2012 - The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize: Blóðhófnir (Blood-Hoof)

2011 - Fjöruverðlaunin - The Women’s Literature Prize: Blóðhófnir (Blood-Hoof)

2007 - The Icelandic Literature Prize: Höggstaður (A Weak Spot)

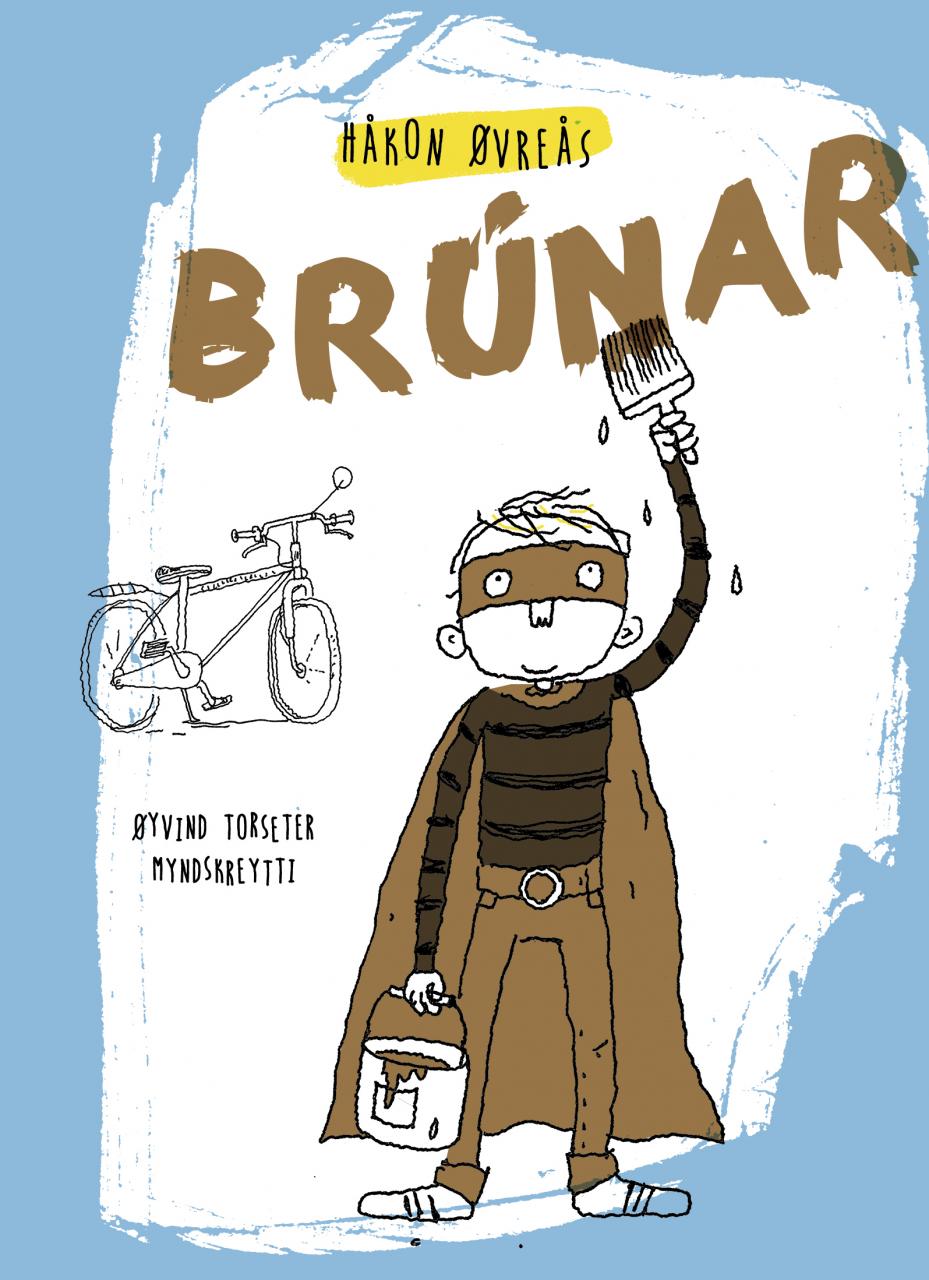

Brúnar (Brune)

Read more