Bio

Jóhann Hjálmarsson was born in Reykjavik on July 2, 1939. From 1956 to 1959 he studied printing at the Technical College of Reykjavik; and in 1959, and again in 1965, he studied Spanish at the University of Barcelona.

From 1967 to 2006, Jóhann worked as critic of both literature and theatre for the newspaper Morgunblaðið. Since 1990, he has also supervised literary broadcastings for the National Radio. Through the years Jóhann has been active in committees of the literary community, including serving on the Nordic Council Minister´s Committee from 1981-1990, acting as its chairman from 1987-1989.

Jóhann has written numerous poetry collections and his first book, Aungull í tímann, was published in 1956. His works have been translated into many languages and published in collections throughout the world. He has, in turn, translated poems and collections into Icelandic.

From the Author

Poetry Is a Song

POETRY is the song of the soul, the voice of that which is within, of that which can only be said in poetry. If poetry speaks for anything or anyone, it is the inner world of that which is so difficult to express.

Poetry could be called the song of someone who cannot sing!

If poetry deliberately becomes the herald of certain “truths,” considers itself to have an urgent message for everyday dialogue or campaigning, there is a risk that most of it will ring hollow. But this does not imply an acceptance that there is an indisputable formula for poetry. A successful poem disproves such theories.

Waiting is important for the poet. The poet needs the patience to be able to wait, even though this may take years or decades.

Why do you write poetry? Poets are often asked this question. There is really no valid answer. The best poetry often comes into being as if spontaneously. The poet hears something like a whisper, a single word or sentence. And has to continue, there is no visible way of escape.

There is no time to wonder why, what the purpose is behind the poem. But if the poem strikes a chord with the reader, some kind of purpose is achieved.

I have at least twice made an effort to challenge poetry, on the second occasion with the express aim of stopping writing it. At first I wrote anti-poetry, poems that were not supposed to be poetry at all but rather imitations of reality, everyday life and everyday speech. It failed. The poem broke in despite my efforts to keep it at bay. I had to bow to the old familiar fact that an anti-poem is still a poem.

These poems or anti-poems are found in particular in the following books: Image of Great-Grandfather (1975), Dairy of a Bourgeois Poet (1976) and From the Circular Balcony (1977).

Then I stopped writing poetry for many years, avoided poetry. That failed too. Poetry came to me, insistent and ferocious. Not only as a haunting whisper, the occasional word, but like a beast gloating over its prey. That beast had merely slumbered in the recesses of the soul.

The last poem in Life is Poetic (1978) is subtitled Closing theme. This not only means that it is the last poem in the book, but is also a kind of statement. The next book did not appear until 1985: Destination Darkness.

Jóhann Hjálmarsson, 2001.

Translated by Bernard Scudder.

About the Author

On Jóhann Hjálmarsson

Unlike most Icelandic poets that came forward before and around the middle of the last century, Jóhann Hjálmarsson is born in Reykjavík. He however partly grew up in Snæfellsnes, in west Iceland. Both these places are of importance in Jóhann’s poetry. He is a city poet, even a bourgoise poet. In 1976 he published a book of poetry with what many found to be a very dubious title: Dagbók borgaralegs skálds (Diary of a Bourgeois Poet). In those days it was not considered classy in literary and cultural circles to be “bourgeois” and to admit to such a poor fate thought to bear witness to an unnecessary courage. But looking past the political challenge invested in the word, it points to Jóhann’s experiments at the time with the so called open poem. The book is what it claims to be and contains “diary entries“ about the everyday life of a Reykjavík family man. Jóhann published at least four books in the spirit of the open poem where the subject is the poetic of the ordinary and small. These texts are straightforward and in part not poetic at all. It is as if the poem dissolves in front of the reader when the spirit of everyday life surrounds it. Jóhann also wrote about his childhood years in the village Hellissandur in the open poem. The book Myndin af langafa (Image of Great-Grandfather) came out the year before Jóhann published the aformentioned political statement. The first stanzas go like this: “Á stofuveggnum hangir mynd./Mér er sagt að hún sé af langafa,/sem ég veit að fór aldrei til ljósmyndara.” (A photo is hanging on our living room wall./I am told it’s great grandfather,/who I know never went to a photographer.) This is by far Jóhann’s most political book. It is a trial to capture the restless air of the cold war era. Perhaps it is an outlet for opinions that poets were not allowed to have, according to many, at this time. But the book is also the poet’s showdown with his background and roots. The photograph on the living room wall is of course that of Stalin, put there by Jóhann’s father. The book is a kind of epic poem (story-in-poem) as Jóhann has said himself and depicts his political upbringing, which is first and foremost marked by his father’s radical leftism and the family’s situation in a small fishing village in the countryside in the middle of the century when there “was unemployment and lack” as stated in the book. The boy absorbs the message and when he wakes up one morning in March 1953 to the news of Josef Stalin’s death, he is startled and realizes the world has changed, this day he felt as if Stalin had been his great-grandfather, like the poem says. Little by little however, the boy sees things in a different light – after traveling to places his father never saw and reading books the father never did, he turns against his upbringing.

These two worlds of city and fishing village have always been important in Jóhann’s poetry, forming a kind of basis for the poet’s identity. The worlds are however three.

When Jóhann published his first book of poetry in 1956, at the age of seventeen, the Icelandic literary scene was in fact a bit strange. It was characterized by conservatism and fear. Maybe because the city was expanding and the countryside shrinking. Old culture, national culture, needed to give way to a new one, an imported city culture. People were shaken by this new development and, in line with old habits, they stood with their bent backs to the wind.

Eight years before Jóhann published his first book, the poet Steinn Steinarr maintained in a review that books were first and foremost written for poets and authors: “that they were a kind of letters from one poet to another, confidential issues, which by nature were incomprehensible and irrelevant to others”. These words well describe the general view towards poetry at the time; the poets were putting an end to the traditional poem by creating free poems with no rhyme and in many peoples’ opinion uncomprehensible. It bears witness to this situation that when Jóhann sent forward his third book of poetry in 1961, Malbikuð hjörtu (Paved Hearts), his publishers asked him to write footnotes to the poems to be published in an epilogue. Jóhann was in fact preoccupied with surrealism at the time, which Icelanders had not heard much about, but this whim shows how absurd modernist poetry was considered to be back then. In the epilogue Jóhann writes that the publishers’ rational was that “they feared that a gap was being formed between younger poets and the general public, that critics did little to bridge this gap, and the poets were after all the only ones who could reach out a helping hand.” He says that at first he asked not to have to explain his poetry, but agreed to it in the end, evidently with hesitation since he asks his readers to forgive him if the result is not as it should be. He goes on to say that he is hoping his effort “has proved to some that the book is not written out in the blue or as a scam, as some seem to think modern poetry is.”

The publishers were likely in some way right about new poetry being more difficult to grasp than what the older poets had written. The modern poet was an offspring of modernism and with it came the demand for a new language. Modernism demanded a radical renewal of the old poetic language that could be used for little else than “to fool those who little do see” as Jóhann points out in his poem Orð (Word). New thoughts about new times had to be put into words and old thoughts put into new ones. This demand obviously affected Jóhann in his first book Aungull í tímann (A Fishhook in Time), it is a very young poet’s effort to hook a few strange fish brought by fresh currents. His second book, in fact called Undarlegir fiskar (Strange Fish), is quite a bit more progressive but it isn’t until Malbikuð hjörtu (Paved Hearts) that Jóhann goes into deep water and catches his first truly strange fish, making publishers take action, without doubt furious over tradition not being able to stand up to teenage verbosity. At this point Jóhann was still a very young poet, only 22 years old. Three years had passed from his last book and Jóhann had used this time, among other things, to travel to South Europe. He stayed in Barcelona for a while and took in the southern influence that to this day has found a place in his poetry, alongside Snæfellsnes and the city.

There was a long pause in Jóhann’s writing after his experiments with the free poem in the seventies and one could say there was an erosion in his career. The form not only becomes more dense and precise but the tone is also heavier and deeper in his next book, Ákvörðunarstaður myrkrið (Destination Darkness), which was published in 1985. The journey between books becomes longer than before: Gluggar hafsins (Ocean Windows) appears in 1989, Rödd í speglunum (Voice in the Mirrors) in 1994, Marlíðendur (Seagliders) in 1998, Hljóðleikar (Soundplays) in 2000 and Vetrarmegn (Winterforce) in 2003. At the same time, the relationship between words and reality becomes more elastic, the communication is more opaque, more introvert. The poems in these books describe a search, an existential one but first and foremost a semantic one – a search for a place or confirmation in language. We do not find here the poet’s certainty about its place within words and things found in the books of the free poem and some of the older ones. The place of being is no longer the familiar every-day one, where there was always a certain harmony between poem and world. Here, the place of being is more opaque and unrecognizable. And existence is a “rough, unsettled, infinite and ruffled ocean” as it says in the title poem of Marlíðendur, definitely one of Jóhann’s best books. The poem is a case in point as regards Jóhann’s subject matters ever since the eighties. The word “marlíðendur” (seagliders) comes from Eyrbyggja Saga and the meaning is “those who glide over the sea”, the ocean. This refers to some kind of strange creatures. The word itself carries with it a certain magic and mystery, which the beginning of the poem hints at: “Ég átta mig á merkingunni, / en óttast að ég gerist / of fornlegur og orðin / taki af mér ráðin.” [I understand the meaning, / but fear that I will become / to ancient and the words / overpower me.] Ancient words and ancient stories hunt the poet and open up to him a new vision of his own times, of man’s fate. The poem ends in this way:

Við marlíðendur sjáum þetta allt,

hugum að ástinni, finnum girndina vaxa.

Hún vekur okkur svo að við líðum

um veröld hinna þróttlausu, heim þeirra

daga sem ekki er okkar heimur, sem er

athvarf þar sem við morknum að lokum sælir

undir mold að kirkju sem við höfum sjálfir látið gera.

Horfin ástríða okkar og blóð,

órólegt, staðfestulaust, óendanlegt og úfið haf.[We seagliders see this all,

think about love, feel desire grow.

It awakens us and we glide

through the world of the weak, the world of these

days that are not our world, that is

a sanctuary where we finally decay happily

beneath earth by a church we had made ourselves.

Gone our passion and blood,

rough, unsettled, infinite and ruffled ocean.]

A deadly uncertainty rules the poem, as if ancient times have the poet in their grip. The demarcation of the two centuries is washed away. Also the line between life and death, or rather the living and the dead. Seagliders are some kind of strange creatures that wander between these two worlds. The seagliders could be the Ulysses of modern times, wanderers with no place to stay, those who haven’t found their place, their peace. These books in other words describe a search for a place in the world, but at the same time a new place in language, a sense of peace in words. After his rebellion against his upbringing, dangerous political statements and surrealistic sidetracks in a flying night-train, words make up a safe place to be in.

Þröstur Helgason, 2004.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 484. 487

Awards

1998 - Grant from The Library Writer’s Fund

1963 - Award from the Artur Lundkvist Translation Fund (Sweden)

Nomination

2003 - The Nordic Council’s Literature Prize: Hljóðleikar

Hugsjór (Mind´s Ocean)

Read moreAllt sem var gleymt er munað á ný (Everything Forgotten is Remembered Again)

Read more

Of the Same Mind

Read more

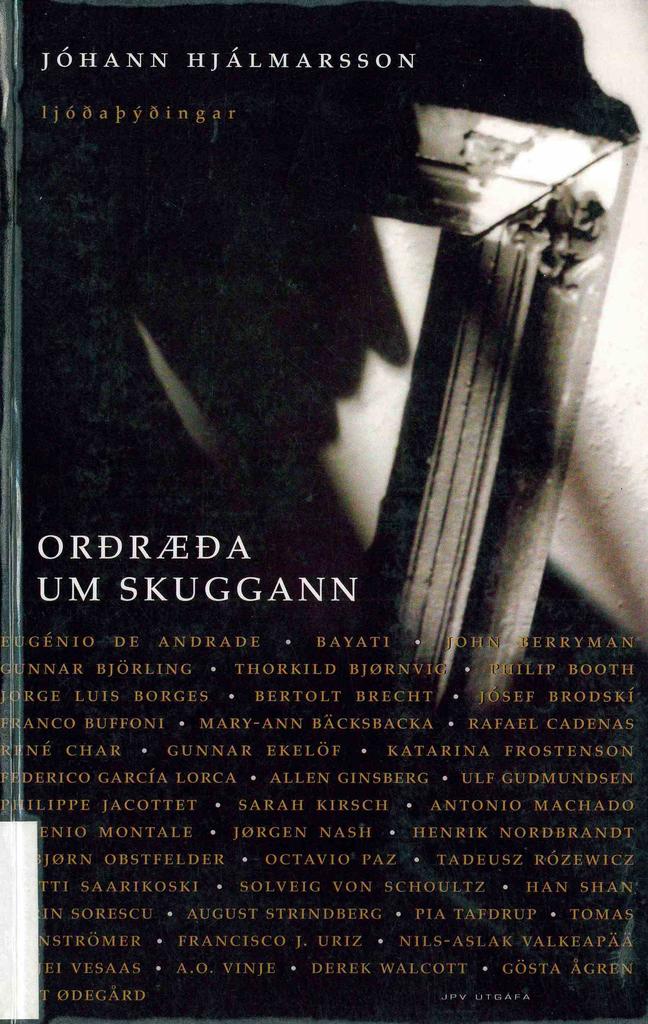

Orðræða um skuggann (A Discourse on Shadow)

Read more

Poems in í 25 poètes islandais d´aujourd´hui

Read more

Vetrarmegn

Read more

Ljóð í Cold was that Beauty... (Poems in Cold was that Beauty...)

Read moreLifað fyrir ljóðið

Read more

Með sverð gegnum varir : úrval ljóða 1956-2000 (A Sword Through the Lips: a selection of poems 1956-2000)

Read more