Bio

Kristján Karlsson was born on January 26, 1922 at Eyvík in Tjörnes in Þingeyjarsýsla South. After completing highschool in 1942 he studied English literature at the University of Berkeley in California, graduating with a B.A. degree in 1945. He went to New York for graduate studies at the Columbia University, completing a M.A. degree in comparative literature in 1947.

Kristján was a member of the board of The Icelandic Literary Society in 1979 and The Patriotic Society, 1984-1985. He also sat on the commitee for the Memorial Fund of Björn Jónsson in 1985. He edited the periodical Islandica from 1948-1952, published by Cornell University in Ithaka. He was the editor of the literary magazine Andvari in 1984 and Skírnir, together with Sigurður Líndal from 1983-1986. Kristján was also co-editor of Nýtt Helgafell from 1956-59. Kristján has written poetry, short stories, essays and articles, as well as being a translator. He has furthermore edited a number of books. He instigated a variety of publications before publishing the poetry collection Kvæði (Poems) in 1976. He was awarded Davíðspenninn (the Pen of Davíð) in 1991 for Kvæði 90 (Poems 90) and The National Broadcasting Service Writer’s Award a year later.

Kristján died in 2014. He was married to Elísabet Jónasdóttir.

About the Author

On the Works of Kristján Karlsson

Kristján Karlsson was born on 26th January 1922 on the farm Eyvík in Tjörnes and grew up in the village of Húsavík in north Iceland. He graduated from the Akureyri Junior College and finished a degree in literature in the United States. He lived in the U.S. for a number of years after his graduation, moved back to Iceland in 1952, and has been a writer since, alongside work in publishing and as an editor. He has written eight poetry books and one short story collection.

Kristján Karlsson had turned 54 before his first book of poems, entitled Kvæði (Poems), came out. Most of his other poetry books bear that same title, with the addition of the publication year. A third of the poems in the first book are written in English and his other poetry books contain some poems in English as well. When his first book was published, Kristján was already a full-fledged poet, and he has been prolific ever since.

Kristján Karlsson is of the “atomic poets” generation and his verse style bears a resemblance to the modernists although he did not become known as a poet until much later than they did. Nonetheless his poems are an anomaly in Icelandic verse. The tempo and mood of many of them is reminiscent of T.S. Eliot, for instance the four-line poems in Kvæði, 1920. Kristján uses the same kind of rhythm in many of his poems: two-line, three-line and four-line. The role of characters in Eliot’s and Kristján’s poetry is sometimes similar as well. It is also obvious from Kristján’s poems that he is thoroughly familiar with the poetry of Ezra Pound. Many of his poems have dedications, allusions and quotes. Not only does Kristján write in two languages, he also uses English as a part of the style in the Icelandic poems, both in headings and individual lines, and other languages also make an appearance. He often uses many forms of alliteration in his poems, as well as other variations on traditional verse, in particular in his first books. His metered poems sometimes have rhyme, sometimes not. Kristján’s poetic language is usually sophisticated, yet unadorned, apart from the fact that he uses the formal mode of address, a custom which the modernist poets had rejected.

Kristján’s poems have an international flavour. Their setting alternates between Iceland and abroad and is usually a city. In one of the books, New York (1983), the poems are all set in the metropolis. They contain images and incidents from the everyday lives of its inhabitants; indeed, some of these people appear in different poems. Kristján has said in an interview that the poems in the book describe actual people who he knew while he was living there. Among the defining characteristics of Kristján’s poetry is the high number of people of diverse nationalities who appear in them, characters who are named or identified in some other way. We learn about who these people are, their whereabouts, daily activities and sometimes their fate. New York contains a poem called “Vor 1945” (Spring 1945) which begins like this:

Djúpt undir tröppu á Eighty-first

býr Adèle Ney frá Paris France.Hvert morgunsár, og Madame Ney

í máðum slopp með úlfgrátt hár.[Deep beneath stairs on Eighty-first

lives Adèle Ney from Paris France.Each daybreak, and Madame Ney

in a faded gown with wolf-grey hair.]

Many of the poems contain meditations and opinions on poetry itself and about the poet’s take on life. “Úr rústum og rusli tímans/reisum vér kvæði vor undir dögun” [From the ruins and rubbish of time/we erect our poems just before dawn] Kristján says in the poem “Kvæði er hús sem hreyfist” (A Poem is a House which Moves) (Kvæði 81 (Poems 81)), displaying the same image of poetry that he has shaped in other poems and prose; the poem must be able to trust in its own worth so that it can withstand all weathers, or else it falls down. In the group of poems “Minnir kvæði á skip?” (Is a poem akin to a ship?) (Kvæði 94 (Poems 94)) it says: “Minnir kvæði á skip, / í einum skilningi / eitthvað sem holt er / að innan? // í öðrum hægfara / gamaldags / flutningatæki?” [Is a poem akin to a ship, / in one sense / something which is hollow / inside? // in another a slow / old-fashioned / transport vehicle?] This question gets a negative answer and in the last poem in the group we are presented with an image of a palace of poetry, which one can approach and have a look at. Kristján does not see the poem as a transport vehicle which transports something to us, but as a building which one can walk around in, look at its interiors and furniture.

The poet is constantly observing the role and value of poetry. Sometimes he also writes about the poetry in nature’s symbols, as in the IX. poem of the group “Is a Poem Akin to a Ship?": “Eins dulið og hreyfing landsins / leggst upphaflegt formleysi / dags þvert á áætlun kvæðis / að binda í ljósi sumars einn væng / við hafsbrún að eilífu í / rím” [As hidden as the movement of the land / lays the original formlessness / of a day at odds with the plan of a poem / to bind in the light of a summer one wing / by the edge of the sea forever in / rhyme].

The subject matter of the poems always tends to assemble characters, maybe with the exception of the poems about nature and poetry. The characters are spoken of or spoken to, and sometimes they communicate themselves or become in some other way a part of the figurative language of the poem. In the poems about people, places and incidents at various times in history, snapshots from a recognisable environment stand out. However, objective reality is often observed with a strong imagination and people’s behaviour described with references to philosophical and cultural history. Nothing is fixed or self-evident: “I fear solutions, and a closed circle” it says at the beginning of the group of poems “Við Viðeyjarsund” (“By the Viðey Channel”) from Kvæði 81 (Poems 81).

The mood of the poems is neutral, also towards the people who appear in them. Beneath the polite observation of the observer there is nonetheless often understanding and empathy, as in one of the most memorable poems about people in a city environment, entitled “Svört ræstingarkona bónar anddyri” (“A Black Cleaning Lady Polishes a Front Hall”) from Kvæði 87 (Poems 87). The poem is a reflection on the culture and social position of black people, as the broom carves dance steps into the stone and “sveip inn í sveip, eins og skeljar / rís fortíðin hálfstigin spor / upp af steininum” [a sweep within sweep, like sea-shells / emerges the past, half-trodden steps / up from the stone].

The wildness of nature is nowhere present in these poems but becomes more so in his later books. The weather and the seasons are still common motifs; the nature images are usually distant and rather chilly, yet they are often linked to a state of mind and contemplation, as in the group of poems “Undir skammdegi” (Kvæði 87), of which this one is the first:

Eitt kvöld grípur vindur

í kulnaða dagsbrún af leik.

Það er kvöld eins og fyrrlangt framundan vor

og óviðkomandi öllu

sem er í þann veginn að gerast:eitt augnablik truflar

rautt yfirskin þunnt

brúna ígrundun fjallsins.[One night the wind grabs

playfully at a frigid horizon.

It is evening as beforefar ahead spring

and irrelevant to all

which is about to take place:for a moment

a red thin brim of light disturbs

the brown contemplation of the mountain.]

Matters of love and emotions matters are not often addressed but the few poems which do are strong and rich in imagery, for instance. “Úr bréfi til Elísabetar” (“From Elisabeth’s Letter”) (Kvæði 94), and one particularly beautiful elegy is “Lone Times” (Kvæði 81):

Um vind sem að eilífu þýtur um glugga þinn

og þrusk hans við sólorpnar dyr:

ég heyri hann stöðugt og hærra nú en um sinnyfir vorvind sem heggur nökt hús og hans högg verða dauf

loks heyri eg þau stopulla en fyr

undir saumsprettuhljóðið af regni sem rásar um lauf;ég þokast í áföngum sumar af sumri til þín

meðan sit ég og hlusta kyr.

Brátt er ég regnið og vindurinn, vina mín.[About wind which forever sweeps by your window

and its soft steps by a sun-warped door:

I hear it always and louder now than I did for a whileOver spring wind which slashes at naked houses, its blows become faint

finally I hear them, less frequent than before

underneath the ripping seam – sound of rain racing through leaves;I inch gradually summer by summer to you

while I sit still and listen.

Soon I become the rain and the wind, my friend.]

The subject matter of Kristján Karlsson’s short stories, a collection of which came out in 1985, resembles his many poems about people and incidents in particular locations. Many of them are set in New York, and they are all about desperate souls and their sad fate, humiliation and often abrupt deaths.

Kristján has been very active as a literary theorist. Many of his articles on literature were published in the magazine Nýtt Helgafell (1956-1959), of which he was one of the editors. As a literary theorist and critic, Kristján was a pioneer of new criticism; and his writings about literature show its influence. The attitudes of new criticism are also prevalent in his poetry; he puts an emphasis on the independent world that the poem contains and communicates to the reader. Besides literary analysis Kristján has also written about the works of other authors and oversaw the publication of the works of Steinn Steinarr, Tómas Guðmundsson, Einar Benediktsson, Stefán frá Hvítadal, Bjarni Thorarensen, Magnús Ásgeirsson, Guðfinna frá Hömrum and Sigurður Nordal. He edited and wrote the preface to Íslenskt ljóðasafn 1.-5. (An Anthology of Icelandic Poetry 1-5), and to the collection Íslenskar smásögur I-IV (Icelandic Short Stories I-IV). Kristján Karlsson’s essays on the aforementioned authors were reprinted and published in the book Hús sem hreyfist. Sjö ljóðskáld (A House which Moves. Seven Poets) in1986.

Kristján has also translated many works, among them are short stories by William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway.

© Eysteinn Þorvaldsson, 2002.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Awards

1992 - RÚV Writers‘ Fund

1991 - Davíð‘s Pen: Kvæði 90

A short story in Kalkül & Leidenschaft

Read more

Kvæðaúrval (Poetry Selection)

Read more

Limrur (Limericks)

Read more

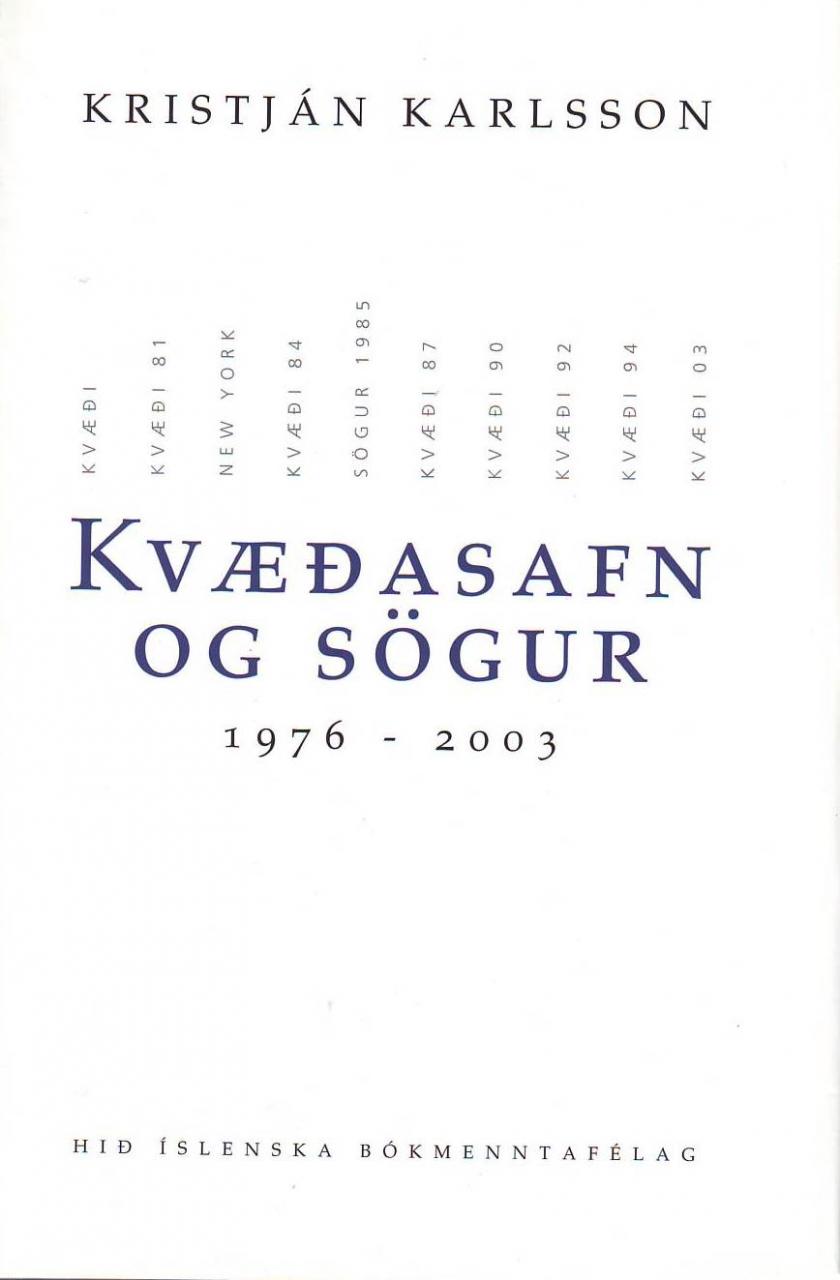

Kvæðasafn og sögur 1976-2003 (Collected Stories and Poetry 1976-2003)

Read more

Kvæði 03 (Poems 03)

Read morePoems in Wortlaut Island

Read moreVoices From Across the Water

Read more

Kvæði 94 (Poems 94)

Read moreHringrásir

Read more