Bio

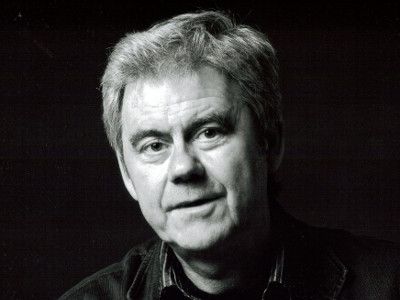

Óskar Árni Óskarsson was born in Reykjavík on October 3rd, 1950 and was brought up in the downtown area of the city (Þingholt). He studied at the Co-Operative College of Iceland in Bifröst from 1969-1971. Óskar Árni published his first book of poetry, Handklæði í gluggakistunni (A Towel on the Windowsill), in 1986. In addition to his writing career, Óskar Árni works as a librarian at the National and University Library of Iceland.

Óskar Árni has published a number of poetry and/or short-prose collections, as well as translating poetry by a number of foreign poets. He has published three books of translations of the Japanese Haiku and has also tackled the form in his own poetry writing. Óskar Árni edited and published the poetry magazine Ský (Clouds), which was issued in the years 1990-1994. Poetry by Óskar Árni has appeared in numerous magazines and collections in Iceland and abroad.

Óskar Árni lives with his wife and their four daughters in Reykjavík.

Publisher: Bjartur.

From the Author

From Óskar Árni

This winter, the Book-Market was held in a fairly new addition to the Trade-School building in Reykjavík. I still remember how cold it was walking up Skólavörðustígur in the narrow-toed Beatles’ shoes, wearing a nylon shirt underneath the thin trench coat. This was in February, sleet in the air and snow on the streets. I must have had some pennies, which was unusual, probably from working at the harbour unloading ships during the Christmas break. The year was sixtyfive or six.

At the book-market there was a table marked Poetry. Loads of unbound (and with uncut pages) poetry books, staring me in the face. Some in a slightly unusual format, bearing names like The Night on Our Shoulders, Shares in the Sunset, or Paved Hearts. I think there were some stacks of new literary magazines, both Birtingur and Helgafell that Ragnar í Smára published. And I seem to recollect that Thor Vilhjálmsson’s books, Maðurinn er alltaf einn and Andlit í spegli dropans had some hold on me. I most likely baught a few books at this market, even if I don’t remember what books they were. Somewhere along these lines, it all started.

Restless stanzas and texts that sea-sawed between poetry and story opened up a new world of words and symbols for me. And my trips up the steps at The City Library in Þingholtsstræti became more frequent. Little by little, the city streets were filled with poetry. A decaying fence and a small dirt road in Grjótaþorp in downtown Reykjavík (it is still there) became washed in mythic light after I read Þórbergur Þórðarson’s book Í Unuhúsi. Ásta Sigurðardóttir’s stories cast flickering silhouettes into dark alleys. Echoes of the atomic poets’ lonely footsteps were carried through the high streets of the city. The rebel poet Dagur [Sigurðarson] set the sun on fire. Something demanded that the images which ran through the mind during this time were put down on paper. The letters started to form words. And a poem was born, hardly standing on it’s feet, but I had found my path – and then, many years later, a check here and another one there started coming in the mail.

The job is not a bad one. To wake up in the mornings, not having to be anywhere in particular to punch in because you are always at work: on your walks, on the bus to Hafnarfjörður, at the café, in the bookstore, while visiting your Aunt. Then, when you have brewed the coffee, you turn on the computer, it is still dark outside and you start hammering away at the keyboard … but then, all of a sudden, the phone rings and you are startled. It’s just old Pegasus. The words you ordered last night are ready, they can be picked up close to ten. This is turning out to be a glorious day. But it can also happen that your order got all mixed up, present instead of past, the colours confused, the nouns having lost their freshness, and when you mean to reach for the evening sun, it becomes clear it got left behind by the road on a milk-stand up north in Skagafjörður.

But, no matter how things go, there is no turning back. You may take a little break, run out to grab a ray of sun, a brick from the sidewalk, or a cloud – and then you continue.

Óskar Árni Óskarsson, 2002.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Óskar Árni Óskarsson: Poems With and Without Words

In the summer of 2000 I participated in a seminar on the poem in the town of Son in Norway. The theme of the seminar was islands in poetry, the idea of the poem as an island and all that. The Norwegians were fearfully worried about the poet’s position in their country, less and less poetry was being read, fewer and fewer copies bought of each published book. Thus the idea about the poem as an island was followed by questions concerning the isolation of that island; the poem could be seen as a kind of floating modest island midst in the world of the entertainment industry, noise and excess. One of the speakers told a story about a speaking parrot that was the only living being that spoke the language of an exterminated race, and his point was that the poem was this lost language – or was the poem the parrot itself, endlessly repeating words that nobody understood? I cannot remember which. In any case I found it difficult to participate in this norwegian pessimism, I found the story about the parrot funny and wonderful, and really liked this crazy idea of the poem being a parrot repeating, without knowing and without understanding, the lost language of a disappeard race.

In addition to this the discussion about the poem as a modest island in the midst of the noisy modern world irritated me, and I felt that this was elevating the poem onto a pedestal, withdrawing it and isolating it even further, rather than trowing it determinately into the stream and letting it find its own feet there – as it is perfectly able to do. So I was bored with this discussion about the crisis of the poem, having already been through all that, when the poem was suddenly condemned as being stagnant, dead, egocentric and eccentric, blabbering about itself in a forgotten tongue that nobody understands and least of all itself. After worriyng about this for a while – and worry I did for I care about the poem – I came to the conclusion that the crisis was rather to be found in the reception, in the all to narrow definitions chosen by the antagonists of the poem. The same argument is made in an article on the British web-zine Prospect (http://www.prospect-magazine.co.uk/Start.asp (January 2002)) on modern poetry in Britain, where Ruth Padell discusses exactly this isolation of the poem and wonders about it. The poem, she says, is perfectly well and nothing is wrong with that, it has continued on its way, matured and changed with time, but the readers on the other hand have grown unused to reading poetry, poetry is not anymore a part of daily life and reading matter as it was before and thus the general population has lost the ability to read poetry. What has to be done, according to her, is to increase the discussion about poetry, increase the use of poetry in the media; help people to unravel the forgotten language of the poem, and thus make it a part of our daily reality again.

It was the artist and writer Hallgrímur Helgason who started a discussion in Iceland on the poem’s crisis in an article in the first issue of the magazine Fjölnir in 1997. Hallgrímur described the poem as being in a bad condition and that this was probably due to the lack of formal restraints, that the free form of the modernist poem did not offer enough struggle with language and thus the minimalistic poems, which he used as examples, fell like the wings of a butterfly in the fall. Poetry had become homogenic and faded, out of connection with anything apart from the inner world of the poet itself.

In a meeting about Icelandic contemporary literature, spring 1999, Guðmundur Andri Thorsson discussed the condition of the poem, and like Hallgrímur he thought it was in a bad way, partly due to the aforementioned egocentricity and lack of connection to everyday life. It actually seemed that Guðmundur Andri was speaking for the return of poetry written for particular occasions.

The reason for my recapitulation of this rather weak discussion, here in an article on the writings of Óskar Árni Óskarsson is that Hallgrímur cited Óskar’s poetry and translations of poetry as examples of what was wrong about Icelandic poetry. In the article, named “The Poem is Limping and Walks with a Haiku” (Haiku is a play on the work ‘hækja’ meaning crutch), Hallgrímur attacks the form that Óskar Árni has dedicated himself to, both as a poet and a translator: the Japanese Haiku. This discussion garnered some notice, and thus there is a good reason to reflect on the modern poem as it appears in Óskar Árni’s haiku and the translation of haiku.

The Japanese haiku is a traditional form that has its roots in past centuries, having always managed to be reintroduced and reinvented for new times – and new worlds, for the haiku has had considerable influence on western poetry, particularly in the twentieth century. In his introduction to the translations of Matsuo Bashô’s haiku’s Óskar Árni says: “The Japanese haiku is a nature poem, an image of a moment, sketch ... It does not actully contain figures of language or similies as we are used to from western poetry.” These images of the moment can be comical as in haiku 136 in Skugginn í tebollanum (1994) by Kobayashi Issa:

Startled

by the frog –

my shadow.

or they can be mysterious as in haiku 147:

Autumn cold

night after night

death-chant of earthworms

In the first haiku the poet mocks himself, the image is very much a scetch, for the reader experiences for himself how unexpectedly the frog jumps into it. The latter is more layered and even carries a threat, the autumn has arrived and the worms are chanting in the earth. Worms refer of course also to something that is buried and thus the image carries a double reference to death, the traditional image of the autumn and the image of the crawling worms. And then of course it is also simply a still image of nature, the air is getting cooler and in the earth the worms feel the change in season – perhaps they are having a meeting?

According to metrics, the form of the haiku is very traditional, the first line is supposed to contain 5 syllables, the next one 7 and the third one 5 again. In his introduction Óskar Árni says that he did not choose to keep too close to the form, rather he attempted to “focus on the haiku’s atmosphere”. And it is clear from his own haiku and his translations of American haiku poetry that a similar approach is chosen and is very successful. Icelanders first met with the haiku in Helgi Hálfdánarson’s translations, Japönsk ljóð frá liðnum öldum (Japanese Poetry from Bygone Age) (1976), and a few years earlier, in 1968, a few haiku by Einar Ólafur Sveinsson appeared in his book of poetry, Ljóð (Poems). Since then few Icelandic poets have written haiku, until Óskar Árni that is. His haiku are varied as are the haiku of the Japanese masters that he translates and all clearly indicate that the poem is at home in this concise and modest form. Óskar is furthermore very successful in adapting the haiku to our contemporary western times. He illustrates how the haiku is neither homogenous nor only inward looking, it is clear and timeless like the mountains, but “From the face of the mountain/it is impossible to read/what age this is” (“Úr svip fjallanna/er ómögulegt að lesa/hvaða öld er”) as it says in Myrkrið kringum ljósastaurana (The Darkness around Streetlights) from 1999.

Óskar Árni Óskarsson’s first book of poetry, Handklæði í gluggakistunni (A Towel in the Windowsill) (1986) is a rather traditional book of poetry divided between poems and short prosepoems. The prosepoems are memory-fragments and that form is to become another leitmotif in the poets books, alongside the haiku. The chapter of prose-poetry is named “Bergstaðastrætið – úr glötuðu handriti bernskunnar” [Bergstaðir Street – from a lost manuscript of childhood] and describes, as indicated by the title, a few recollections. The neighbour falls from a stair, the boy is taking a bath in a steamfilled washing room, he is crawling through the window of a ghost-house.

In his second book of poetry, Einnar stjörnu nótt (A One Star Night) (1989), there are poems that bear the mark of the haiku, as for example “Litbrigði: fyrir munnhörpu og strengi” [Iridesence: for a Harmonica and Strings]; one of the verses goes like this: “At a bluestreetcorner/in the autumn rain/sad” (“Á blágötuhorni/í haustrigningunni/dapur”). Óskar Árni’s third book of poetry is dedicated to the haiku, or variations thereof, Tindátar háaloftanna (The Tin-soldiers of the Attics) (1990) is in three parts, the first and the longest is a kind of a collection of haiku about tin-soldiers and starts like this: “sometimes/it is as if the attic/is full of tiny/thoughts” (“stundum/er eins og háaloftið/sé krökkt af örsmáum/hugsunum”). Then the tin-soldiers’ existence in the attic is described, their story is recollected and images flash: “through the empty goldfish bowl/with the castle-ruins at the bottom/they watch each other with wonder” and “told in whispers/strange stories about soldiers/of flesh and blood” (“gegnum tómt gullfiskabúrið/með hallarrústinni á botninum/horfa þeir undrandi hvor á annan” og “sagðar í hálfum hljóðum/furðusögur um dáta/af holdi og blóði”). And sometimes it is like these soldiers are made of flesh and blood, for images of a real war flash here and there and are brilliantly interwoven with the tin-soldiers’ memories. A referense to H.C. Andersen appears on the cover, citing the tin-soldier who wanted to go to war and has clearly been the inspiration for this section, and in one of the haiku where a gust of wind leaves through H.C. Andersens’s fairy tales.

In Norðurleið (Northbound) (1993) Óskar Árni continues to focus on the haiku, either in long poems like “Going North” (“Norðurleið”) or as various sudden images like in the section “Haiku” (“Hækur”). On the way north the poet sees “a graveyard-gate/bound shut/with a black tie” (“kirkjugarðshliðið/hnýtt aftur/með svörtu hálsbindi”) and “a daddy longlegs on the windowpane” (“hrossafluga á rúðunni”) when he looks “up from Issa/in Haganesvík –“. (“upp úr Issa/í Haganesvík –“.) Thus many of Óskar’s poems refer to his translations and turn them into a kind of a theme in his own poetry. In haiku 21 in “Haiku” there is “a blizzard -/drink the tea,/impossible to get to Tokyo” (ath ófærð) )“blindbylur -/ sötra teið,/ófært til Tókýó”) and in Ljós til að mála nóttina (A Light to Paint the Night) (1996) there are references to the east, this time China, as one of the poem is named “To Li Po” (“Til Lí Pó”) and another “A Hand that Disappears and a Butterfly Describes a Battle” (“Hönd sem hverfur og fiðrildi lýsir orustu”):

The darkness so black

that when I hold out

my hand it disappearsbut appears again

with a longbearded butterfly

that starts to describe

a famous battle in China

thousand years agowarflags stream

a bloodred sun

armours and wagons

are buried in eartha glitter

of wings(Myrkrið svo svart

að þegar ég rétti fram

höndina hverfur húnen birtist á ný

með síðskeggjað fiðrildi

sem fer að lýsa

frægri orustu í Kína

fyrir þúsund árumgunnfánar blakta

blóðroðin sól

brynjur og vagnar

verpast molduþað glampar

á vængi)

The contrast between the butterfly and the battle seems perhaps rather traditional but takes on a new image with the closing lines, where the butterfly suddenly seems to be a participant in the battle. In the prose-poem “Sólheima-branch, 4. 4. 1994” (“Sólheimasafn, 4. 4. 1994”) in Vegurinn til Hólmavíkur (The Road to Hólmavík) (1997) the narrator finds “a curious book, Reflections on indolence by the ancient Japanese thinker Kenko.” (“fortvitnilega bók, Hugleiðingar um iðjuleysi eftir japanska fornspekinginn Kenko.”) He borrows the book and dissappears into the darkness, like he does later in the same book, in poem no. 10 in the chapter “Three golden plovers on Landakot’s Lawn: Images from the City” (“Þrjár lóur á Landakotstúni: Borgarmyndir”), where the narrator jumps onto a bus outside Bústaða church “with twothousand Japanese poems in my coat jacket” (“með tvö þúsund japönsk ljóð í frakkavasanum”), having probably got them at the library:

The January darkness crouches over the Bústaða neighbourhood. Extremely cold and deep snow. The path that runs through the neighbourhood has just been cleared and the frosen snow glitters. The path goes through a kind of a secret garden, a fairly large public garden with lonely looking benches and a small playground, surrounded by high trees and frosen windows of the night. A late mass is starting in Bústaða church and the library in the church’s basement is about to close. Starting to get more windy and the northern lights jangle when I jump onto the bus with twothousand Japanese poems in my coat jacket.

(Janúarmyrkrið grúfir sig yfir Bústaðahverfið. Brunafrost og kafsnjór. Nýbúið að ryðja göngustíginn sem liggur um hverfið og það stirnir á hjarnið. Stígurinn liggur í gegnum hálfgerðan leynigarð, allstóran almenningsgarð með einmanalegum bekkjum og litlum barnaleikvelli, umlukinn háum trjám og frosnum gluggum kvöldsins. Aftansöngur að hefjast í Bústaðakirkju og bókasafnið í kjallara kirkjunnar um það bil að loka. Farið að hvessa og glamra í norðurljósunum þegar ég skýst upp í strætisvagninn með tvö þúsund japönsk ljóð í frakkavasanum.)

In this way Óskar Árni plays with the truthfulness of the narrator in his prosepoems and haiku, frequently conflating him with himself – but the reader should avoid taking that similie too literally for even though many of the prosepoems appears as memories, this is not always so. It would for an example be risky to take the prosepoem “Night at the Bus Terminal” (“Kvöld á Umferðarmiðstöðinni”) as a biographical source. The narrator is beleaguered by a dark eyed service girl who pushes Tímarit Máls og menningar (a cultural magazine) and asks was it not him who forgot a pink lipstick there the night before. The narrator gives up on the bus and takes a taxi and sees Tímarit Máls og menningar in the passengerseat beside the female taxi driver. In one of these restrained uncanny postmodern moments the narrator is dying to tell her that he has a short story in this issue, and when he arrives home he sees a faded pink lipstick on his lips. In this way time is collapsed around an uncanny lipstick that is also connected to the scar on the shaven head of the taxi woman and is in some way strangely connected with Tímarit Máls og menningar.

The bus would not leave for an hour, so I decided to order lamb chops with sugared potatos. The dark eyed girl at the counter asked if it had been I who had passed by here last night leaving a pink lipstik. The sarcasm in her voice was unmistakable, but I just smiled and said that this was rather unlikely. She clearly did not believe me, and then offered me a anniversary subscription to Tímarit Máls og menningar. I thought she was being a bit insistent and was starting to get angry. I told her the truth, that my wife subcribed to it. She looked at me stricktly and spat out: No hot food after nine. Finally I bought myself a sandwitch and took a taxi to Vogar.

A woman drove the car. Her head was shaven and she had a conspicuous scar at the back of her head. Laying on the seat beside her was the most recent issue of Tímarit Máls og menningar. I tried to be inconspicuous in the backseat the whole way even though I was dying to point out to her that I had a short story in this issue.

When I came home and looked in the mirror in the hallway I could see that the faded pale pink lipstick was still visible.

(Það var klukkutími þangað til rútan færi svo ég ákvað að panta mér kótelettur með brúnuðum kartöflum. Dökkeyga stúlkan við kassann spurði hvort ég hefði ekki átt leið hérna um í gærkvöldi og gleymt bleikum varalit. Hæðnistónninn í röddinni leyndi sér ekki, en ég bara brosti og sagði að það væri nú frekar ólíklegt. Hún horfði vantrúuð á mig, en bauð mér síðan afmælisáskrift að Tímariti Máls og menningar. Mér fannst hún vera orðin nokkuð ágeng og það var farið að þykkna í mér. Ég sagði henni eins og var að konan mín væri áskrifandi. Hún leit þá eldhvasst á mig og hreytti út úr sér: Enginn heitur matur eftir klukkan níu. Þetta endaði með því að ég keypti mér samloku og tók leigubíl suðrí Voga.

Það var kona sem ók bílnum. Hún var krúnurökuð og með áberandi ör á hnakkanum. Í sætinu við hliðina á henni lá nýjasta heftið af Tímariti Máls og menningar. Ég lét ekki á mér bera í aftursætinu alla leiðina þó mig dauðlangaði að benda henni á að ég ætti smásögu í þessu hefti.

Þegar ég leit í spegilinn á ganginum heima sá ég að enn vottaði fyrir fölbleikum varalitnum.)

This subtle undertone and a slight air of mystery is characteristic of Óskar Árni’s poetry; he excells in mingling humour, joy, sorrow and menace in a quiet and effortless manner. At first the poems seem to be light and bright – and they surely are – but given closer inspection all kinds of nuances appear. Óskar Árni has probably learned this from the haiku, which sometimes does not seem to say anything, but can at the same time say everything that needs to be said about the world, as he puts it himself in aforementioned introduction to his translations of Matsuo Bashô. These nuances appear so beautifully in a simple image that is painted in haiku number 12 in the haiku section “Road Signs” “Vegvísar” in Myrkrið kringum ljósastaurana, where the “Evening fog/has stolen away/with the shark shed” (“Kvöldþokan/hefur stolist burt/með hákarlahjallinn”). The humour is obvious in the idea about the fog that is sneaking away with the shark shed, but at the same time a strange threat is also lurking; that the fog has power to abduct houses and road marks, that what it is hiding has disappeared. Furthermore there is also an intimation of the silent lethal shark, that is hiding under the fog of the ocean surface and can attack at any time.

The title of the book flashes an image of darkness and light and this image of fog that erases features and swipes houses away interacts with lights and stars that glow here and there in windows – and on hatbrims as in the poem “Night in Arles” (“Nótt í Arles”) where the painter goes out to the field in the middle of the night, “sticks the candlestubs/onto the brim of his hat/-and starts paining” (“festir kertisstubbaana/á hattbörðin/-og byrjar að mála”). Another sudden change of light appears in “An Unexpected door” (“Óvæntum dyrum”):

Sometimes it happens

Like an illuminated

coastal cruiser

sailing a dark fjordall at once

a door opens

between worldsthe world

so much greater

than you remembered(Stundum gerist það

eins og uppljómað

strandferðaskip

sigli dimman fjörðallt í einu

opnast dyr

milli heimaveröldin

svo miklu stærri

en þig minnti)

Still we are reminded of the idea behind the haiku, that is contains at the same time the small and the large. One could say that this idea is taken all the way in the wonderfully beautiful poems without words that appeared in the 25th issue of the literature magazine Tímarit Bjarts og frú Emilíu. There an ode to the typewriter was written, in letters forming images: a group of proud i-s carries the caption “Literal Believers” (“Bókstafstrúarmenn”), horizontal brackets, upright i-s and commas from the sky are “The Umbrellas in Prague” (“Regnhlífarnar í Prag”), and an i within horizontal brackets is being carried to its grave by a line of i-s in “A Funeral in Rain” (“Jarðarför í rigningu”), outside the row of i-s four others stand, three grouped together and one apart. And “Gunnar at Hlíðarendi” (“Gunnar á Hlíðarenda”) must not be forgotten, he appears as an i who proudly raises the bracket bow and defends himself from the attack of a group of horizontal i-s. For me these poems are an example of poetry in its purest form, where rich imagery and play with language go together as succinctly as possible. On of the problems with modern poetry, according to Hallgrímur, was how short and few of words it is, each book hold a couple of poems residing tiny in the middle of a white page. This illustrates the egocentrism and the lack of purpose, he claimed.

Poems without words are a very good example of the idea of the poem as a kind of a minimalistic art on an empty page, but instead of prowing the pointlessness of this, Óskar Árni’s poem without words are excellent illustrations of the many and different possibilities of the poem. If any poems are open, variable and accessible, these are, and they are good for any occasion. This I have found out by using these poems for many years in my teaching and various lectures. Whether on reflections on imagery, visual culture, art or literature, these poems always open the eyes of the audience for deliberations on oppositions, (ath) between the comparability of images and words, for the interplay of simplicity and variability, and, last but not least, for the possibilities of poetry. The most memorable lecture was in a department of economics, where students got quite enchanted by these worldless poems and became very imaginative playing with possible interpretations – having at the beginning announced a limited interest in poetry. Who are these standing outside the main funeral group? they asked and answered themselves: the one he was having an affair with! and thus whole stories were spun around these very few letters and symbols.

To spin stories around a small number of moments and events is exactly what Óskar Árni does in his prose-texts, but beside the prose-poems that appear in his books of poetry he has also published two books of short proses, that can be categoriesed somewhere between short stories, micro-stories and prose-poems. One of them is the aforementioned Vegurinn til Hólmavíkur and the other is called Lakkrísgerðin (The Licorice Factory) (2001), where the prose-texts are a bit longer than the ones we have met with before in Óskar Árni’s work. This is not a bad thing though, quite the contrary, for this book is probably the author’s best and most cohesive work to date, full to the brim of wonderful images, reflections and remarkable happenings, described by Óskar in his peculiar way. Many of the proses are reminiscent of the writings of the Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges, in the way that thoughts, dreams and memories merge with reality, in “Travelling” (“Ferðalög”) a woman is seen on a city map, we meet her again in a bookshop, and then finally on a new map. A robin addresses a woman in German, not knowing that she has a water-pistol in her bag, in “A Woman and a Bird” (“Kona og fugl”), and in “Doris Day” Dísa in the country cottage (a character from Icelandic poem) takes on the image of the actress. “Heavy Snow” (“Snjóþyngsli”) become the source of a Russian atmosphere in Fljótin, where warmly dressed young girls travel around in dog-sledges and read Anna Karenina in Magnús Ásgeirsson’s brand new translation and on a single walk around town one can meet a whole flock of poets, living as well as dead, and discuss “Umbrella or Peppermint” (“Regnhlíf eða piparmyntur”) with them. Books, reading and literary themes characterise many of the stories, and then it appears that the “Library” (“Bókasafnið”) is really a spacestation:

It was like the whole street was alife; houses with eyes wide open, the fire hydrant, shadows in the gardens and trees strethcing their arms across the fences. The evening flows through him and new feelings and experiences stir within him. The whole city was breathing and he thought that thousand lips were whispering in the darkness. And there the library waited like a lighted spacestation ready to take him away to other planets. He saw the people in the house reach out for books.

And as he ran up the stairs he heard himself count the steps ... ten nine eight seven ...(Það var eins og öll gatan væri lifandi; húsin með uppglennt augun, brunahaninn, skuggarnir í görðunum og trén sem teygðu handleggina yfir grindverkin. Kvöldið streymir í gegnum hann og nýjar kenndir og skynjanir bærðust með honum. Öll borgin andaði og honum fannst þúsund varir hvísla í myrkrinu. Og þarna beið bókasafnið eins og uppljómuð geimstöð tilbúin að flytja hann til annarra hnatta. Hann sá fólkið inni í húsinu rétta út hendurnar eftir bókunum.

Um leið og hann hljóp upp tröppurnar heyrði hann sjálfan sig telja þrepin ... tíu níu átta sjö ...)

And then he is presumably airborn, as the reader of Lakkrísgerðin. Myrkrið kringum ljósastaurana contains the poem “The Magical Mouse” (“Galdramúsin”) by American poet Kenneth Patchen, where the magical mouse is described, it does not eat cheese but sunsets and the tops of trees. It does not wear fur, but “funnels/Of lost ships and the weather/That’s under dead leaves”. (“klæðist reykháfum/týndra skipa og veðrinu/undir visnuðu laufi”) This mouse does not fear cats or woodsowls, it does what it pleases and eats little birds “-and maidens//That taste like dust” (“-og smámeyjar//sem bragðast eins og ryk”):

I am the magical mouse

I don’t eat cheese

I eat sunsets

And the tops of trees

I don’t wear fur

I wear funnels

Of lost ships and the weather

That’s under dead leavesI am the magical mouse

I don’t fear cats

Or woodsowls

I do as I please

Always

I don’t eat crusts

I am the magical mouse

I eat

Little birds – and maidensThat taste like dust

(Ég er galdramúsin

ég borða ekki ost

ég borða sólsetrin

og krónur trjánna

ég hef ekki feld

ég klæðist reykháfum

týndra skipa og veðrinu

undir visnuðu laufiÉg er galdramúsin

ég hræðist hvorki ketti

né skógaruglur

ég geri það sem mér sýnist

ævinlega

ég borða ekki brauðskorpur

ég borða spörfugla

- og smámeyjarsem bragðast eins og ryk)

This magical mouse is quite similar to the poem itself as it appears in Óskar Árni’s approach to it. Like the spare haiku it is not large, but its small body contains joy and power and it can span sunsets as well as treetops and dresses in the fine breeze of something that is out of sight. The poetic mouse of the magic is not scared of anything for it is able to catch little birds and little girls before they get changed into dust.

Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir.

Awards

2006 – The Jón úr Vör Poetry Prize: For the poem “Í bláu myrkri” (In Blue Darkness)

2004 – The Icelandic National Broadcasting Service (RUV) Writer’s Fund

Nominations

2017 – The Icelandic Translators‘ Award: Neyðarútgangur (Selected poetry) by Ewa Lipska (with Áslaug Agnarsdóttir, Magnús Sigurðsson, Olga Holownia and Bragi Ólafsson)

2010 – The Icelandic Translation Prize: Kaffihús tregans (The Ballad of the Sad Café) by Carson McCullers

2008 – The Icelandic Literature Prize: Skuggamyndir úr ferðalagi (Silhouettes from a Journey)

Reykjavíkurmyndir (images of reykjavík)

Read more

Kúbudagbókin: anno 1983 (The Cuba Diary: anno 1983)

Read more

Fjörutíu ný og gömul ráð við hversdagslegum uppákomum (Forty Old and Recent Bits of Advice for Mundane Situations)

Read more

Eftirherman (The Impersonator)

Read more

Translations in Styttri ferðir

Read more

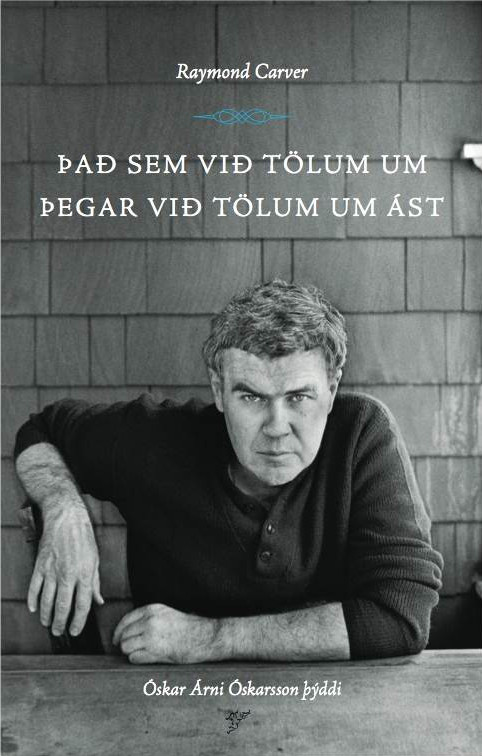

Það sem við tölum um þegar við tölum um ást (What We Talk About When We Talk About Love)

Read more

Kuðungasafnið

Read more

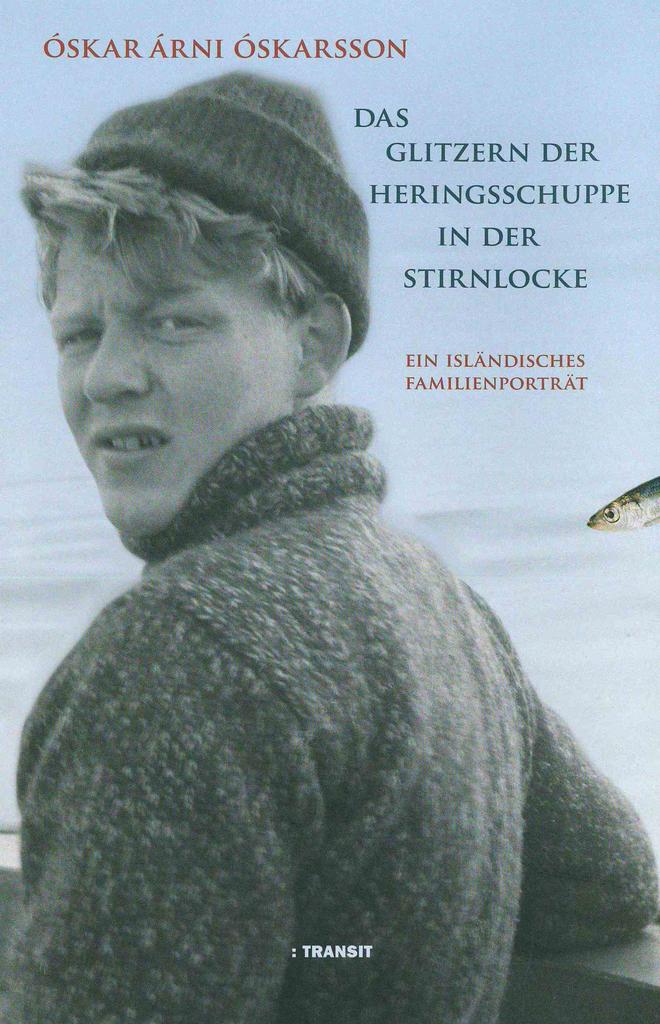

Das Glitzern der Heringsschuppe in der Stirnlocke. Ein isländisches Familienporträt

Read morePoems in Neue Lyrik aus Island

Read more