Bio

Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir was born in Reykjavík on May 1, 1953. She graduated as a teacher from the Icelandic Teacher’s School in 1973 and finished her degree in art history from the University of Århus in Denmark in 1979. She also studied at the Icelandic Art Academy and read literature at the University of Iceland.

Ragnheiður worked as a teacher at different schools in the capital area in Iceland for a number of years and was an editor at The National Centre for Educational Material from 1990 – 1996. She is both an illustrator and children’s book writer, and has published a number of books for children and teenagers. Her first book, Ljósin lifna (The Lights are On), was published in 1985. She has also retold and illustrated Icelandic fairy tales.

Ragnheiður’s books for teenagers have been well received by readers and critics alike. She won the Icelandic Children’s Book Award in 2000 for her book Leikur á borði (A Winning Chance). She is a two time winner of the Reykjavík Children’s Book Prize, in 2001 for the book 40 vikur (40 Weeks), and in 2004 for Sverðberinn (The Swordbearer). Ragnheiður received the Nordic Children’s book Prize for the latter book in 2005.

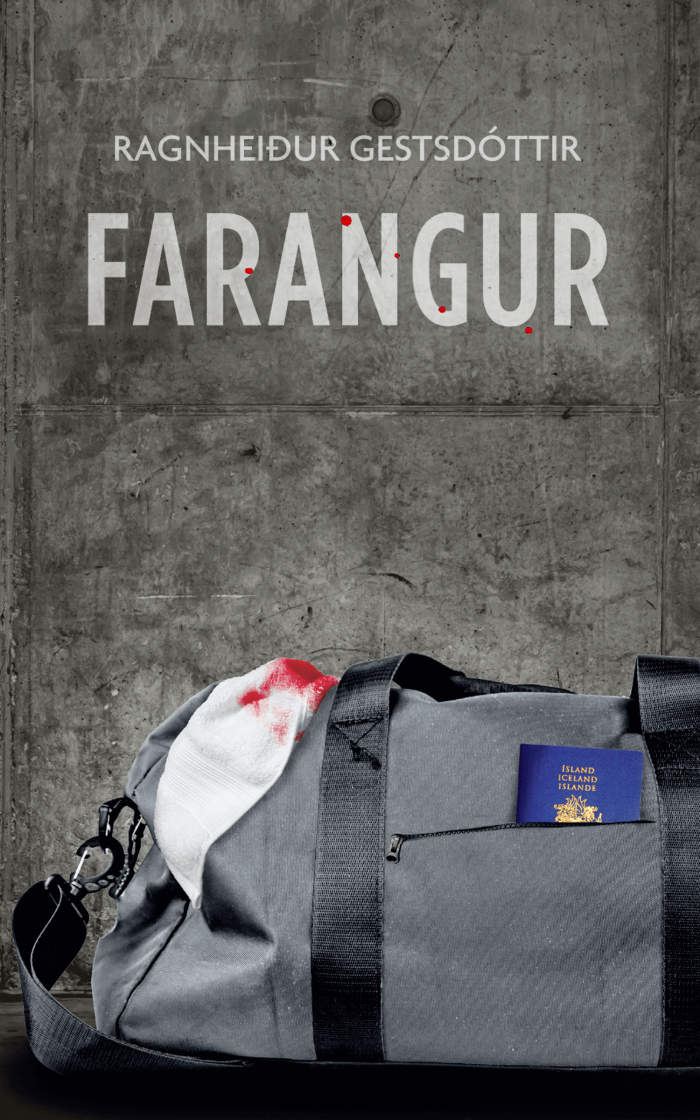

Ragnheiður has also written books for adults and in 2022 she received the Drop of Blood, a crime fiction prize for her novel Farangur (Luggage).

Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir lives in Hafnarfjörður in the capital area of Iceland. She is married and has four grown children.

Publisher: Mál og menning.

About the Author

On the Works of Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir

Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir’s first novel, Leikur á borði (A Winning Chance, 2000), received The Icelandic Children’s Book Award in 2000. A Winning Chance introduces Sóley, a young girl living with her mother in an old yet comfortable house while Sóley’s father lives overseas when the story begins. Sóley’s mother is a musician so deeply immersed in her art that Sóley must assume the responsibility not only for her own upbringing, but also for the household and her rather absentminded artistic mother. Sóley is an excellent student, but has no friends at school. Sóley’s piers and classmates unite to bully her without any real reason, which the text explains is frequently the case with bullying. Sóley does however differ from other children in that she has a great sense of duty and her calm and quite personality is one of the ostensible reasons she is regarded as a teachers pet – reason enough for the other children to make her the constant object of practical jokes and malice.

When a new girl joins the class, Sóley’s life changes. While the new girl, Linda, does not replace Sóley as the object of general derision, her arrival does shift the focus of attention away from Sóley for a time. Linda however, is ‘cool’ and doesn’t let a lot bother her. A bond of understanding is slowly forged between Sóley and Linda although neither girl can at first explain or even comprehend the reason for this connection. Linda protects Sóley from their fellow classmates’ attacks yet initially remains aloof in her behaviour toward Sóley. Sóley at first finds Linda hard to fathom but in time the two girls develop a deep friendship and Sóley realises that like herself, Linda must assume great responsibilities at home. Not only does Linda take care of her younger siblings but also shares her parents’ concerns for the family’s finances.

As the friendship between Sóley and Linda deepens, Sóley’s father moves back to Iceland, accompanied by his new wife. It is hard for Sóley to accept these changes in her father’s life and to share him with another person because, as is often the case with children of divorcees, Sóley has secretly entertained the hope that her parents will get together again even though her heart tells her that this is unlikely to happen. Emotionally vulnerable at this point, the last straw comes when Sóley’s classmates attack her at school. The kids hurt Sóley badly and she suffers for a long time, more emotionally than physically. This attack reveals to her parents how much responsibility Sóley has taken upon herself and how many concerns their daughter has kept secret in order to spare them.

The two friends Linda and Sóley are there for each other and together they shoulder burdens neither of them could have born alone. While the author discusses bullying through the experience of a girl whose new friend helps her escape it to some extent, Rangheiður does so soberly and realistically in a way that avoids clichés and sentimentalism. In no way is bullying romanticised. Rather, the evils it causes are used to highlight the importance of friendship and demonstrate how necessary it is that parents play an active role in their children’s lives, as a large proportion of the both Linda’s and Sóley’s problems are shown to be directly derived from inattentive parents.

The novel’s title – A Winning Chance – refers to the fact that Sóley and her grandfather like to play a game of chess whenever Sóley visits her grandparents who provide much needed stability in her life. The title also alludes that life can change swiftly, or just in one move.

40 Weeks

Rangheiður’s next novel, 40 vikur (Forty Weeks, 2001), was well received, and deservedly so. The main character, Sunna, is just finishing compulsory education when the story begins. To celebrate having completed the last exam she gets together with some friends, including the most popular boy in her year, Biggi. For the first time in her life Sunna feels unrestrained, witty and like a desirable young woman rather than a little girl. Both a little tipsy yet mostly lucid, Sunna and Biggi spend the night together and Sunna has her first experience of sex. Eventually however, she starts to suspect that all is not as it should be and anxiously starts counting days. Over and again she calculates the time elapsed since her last period but soon realises that she is most likely pregnant. When Sunna finally musters the courage to buy a home pregnancy test, her suspicions are confirmed: she is pregnant. Sunna then goes through a difficult period of great emotional turmoil and doubt but at last shares the news of her condition with her mother. Sunna’s mother advises her to have an abortion, but as it is already to late in the pregnancy for that solution, Sunna decides, albeit without much real choice, to have the baby.

Superficially, Sunna’s life does not change much throughout the pregnancy. College starts, she hangs out with her friends and attends choir practice. But her feelings are still very raw and unsettled. Biggi is no longer part of her life and the prospect of caring for and raising a child on her own seems to Sunna an almost insurmountable obstacle. Her future, previously so clear and organised, now appears clouded and confused; all the hopes she had entertained for a career seem unrealistic and even preposterous.

On top of these bleak thoughts Sunna’s health suffers during the pregnancy. A near miscarriage however results in Sunna finally accepting what she has previously tried to deny: that she has developed strong feelings for her unborn child. After the incident Sunna decides to accept her changed circumstances and subsequently her character and views start to mature significantly. Previously a confused teenager she now evolves into a responsible mother-to-be. When Sunna’s daughter is born at the end of the book she has become a strong individual who knows what she wants and fights for what she feels is important.

Sunna’s emotional journey throughout the text is very realistic and invites the reader to consider that it is possible to turn unexpected events into positives. Sunna is such a well-conceived character and her experiences while pregnant so poignantly and beautifully rendered that the reader’s sympathy is easily aroused.

The Swordbearer

Ragnheiður’s latest novel, Sverðberinn (The Swordbearer, 2004), is similar to her earlier work in that it is a tale of emotional growth, but otherwise the story differs quite significantly from her previous novels. The Swordbearer tells the story of teenager Signý who uses role-play to escape the harsh realities of her home life – feuding parents and an addict brother. The past also conceals a serious accident involving her brother, an accident that has created barriers between family members.

Role-play offers an opportunity for a few intimate friends to come together and escape into a fantasy world of their own creation, a world subject to other laws than the more mundane reality. Participants in the game create characters to play through yet role-play resembles a board game rather than improvised theatre.

When the story begins, Signý is on her way to a meeting with the role-play group. The evening proves fateful in that she and one of the companions, Hlynur, realise that they have fallen in love with each other. The evening however ends in disaster – the group is caught in a serious car accident that leaves Signý and Hlynur critically injured. Signý is initially kept comatose and on a ventilator, but as her health improves the vent is removed and Signý’s awakening awaited. While devastating, the accident impacts positively on Signý’s family who are thrown together in the aftermath and forced to face up to and discuss past problems and old wrongs, such as Signý’s parents’ guilty sense of responsibility over her brother’s addiction.

Signý’s comatose state continues far longer than her doctors had expected, but it is caused by a phenomena neither physicians nor Signý’s family could have fathomed. Signý has slipped into a world of fantasy; the reality created by her and the role-play group. In the realm of imagination Signý has been charged with a heavy a duty, but receives aid from shadows or reflections of the characters her role-playing friends created for the game.

Darkness has engulfed the fantasy world because the Elf Queen, who has long been its ruler, has turned to evil and now subjects her people to a cruel reign of terror. Signý must defeat the so-called Ice Queen and restore the world to light and happiness. The tasks she must complete to achieve this goal are very difficult and mirror the physical hardships her injured, comatose body must endure while recuperating from the accident.

Having successfully freed the Elf Queen from her bonds of shadow and evil and thus restored happiness to the realm, Signý must chose whether to remain in this world or return to her own. Her choice is between a place where she has made good friends and is regarded as a hero and a reality where she has both friends and family but cannot remember while she remains in the fantasy world of role-play.

Paralleling Signý’s fairy tale adventures is the story of her relatives and friends who remain in the real world. Hlynur, partially paralysed since the accident, visits Signý’s sickbed regularly and so does Signý’s brother who had not had any contact with the family for years. Her grandmother is also a frequent visitor and often fills the silence by repeating the fairy tales she used to tell Signý when she was younger. At times it sounds like the grandmother suspects what Signý is experiencing in her sleep.

The Swordbearer is admirably written with convincingly drawn characters that leap lifelike from the page. Also convincing is the world Signý finds herself in after the accident. With this book Ragnheiður demonstrates that not only is she master of realism, but that she can furthermore construct a believable fantasy world of fairies and old Icelandic folk tales.

Signý’s family’s responses to the accident are also engaging in a very real way. Readers who have experienced tragedy in their own lives will recognise the characters’ emotions and know that shared grief brings family members closer together, forcing them to deal with issues that have been allowed to fester in order to gain inner peace.

Ragnheiður’s novels generally fall under the heading of realism. She manages to avoid being pedantic yet her novels do not suffer from the sentimentalism or romanticising, which is often the case with realist novels for young people. The reader can easily identify with the main characters and sympathises with them throughout the story. As a writer, Ragnheiður obviously has great respect not only for her characters but importantly also for her readers. Her writing is never patronising and she never makes light of her protagonist’s feelings. Problems are dealt with as they arise, from perspectives easily recognisable to the reader, and these are thoughtfully solved without resorting to overly simplified or quick solutions.

In addition to writing novels, Ragnheiður has produced a plethora of educational and easy reading material for children and young people, including Sögusteinn. Ragnheiður has also rewritten and illustrated well-known Icelandic fairy tales such as Sagan af Hlina konungssyni and Líneik og Laufey. She has also revised the fairy tale Karlsson, Lítill, Trítill og fuglarnir, published with illustrations by Anna Cynthia Leplar.

© María Bjarkadóttir, 2005.

Translated by Agnes Vogler.

Awards

2022 - The Drop of Blood; a crime fiction prize: Farangur (Luggage)

2009 – Dimmalimm, the Icelandic Illustrator’s Awards: Ef væri ég söngvari (If I Were a Singer)

2005 – The Nordic Children´s Literature Prize: Sverðberinn (The Swordbearer)

2005 – IBBY Iceland Award for her writings for children

2004 – The Reykjavík Children´s Literature Prize: Sverðberinn (The Swordbearer)

2001 – The Reykjavík Children´s Literature Prize: 40 vikur (40 Weeks)

2000 – The Icelandic Children´s Literature Prize: Leikur á borði (A Winning Chance)

Steinninn (The Stone)

Read moreHún horfir lengi áður en hún skilur hvað það er sem stendur fyrir framan hana á grasflötinni. Og þegar hún loks skilur það, þá vill hún ekki skilja. Brosið deyr hægum dauðdaga. - Sigfús. Þetta er steinn. Þetta er legsteinn.

Blinda (Blindness)

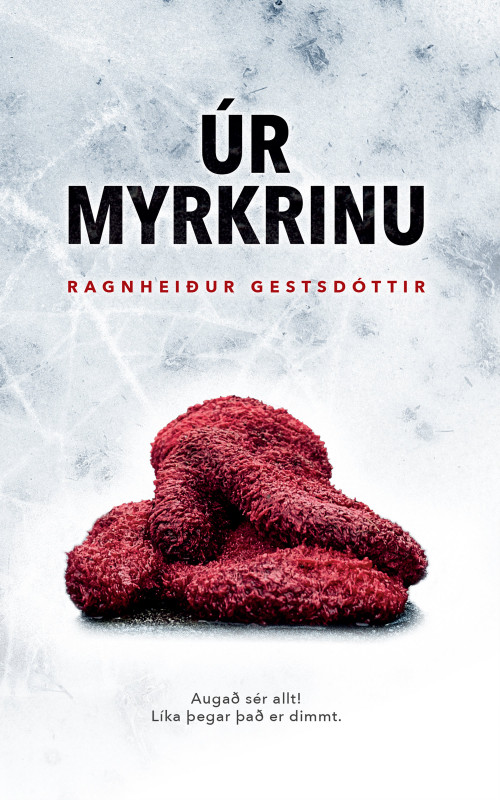

Read moreBlinda er þriðja glæpasaga Ragnheiðar Gestsdóttur. Fyrri bækur hennar eru Úr myrkrinu og Farangur sem hlaut Blóðdropann árið 2021 og er tilnefnd til Glerlykilsins 2023

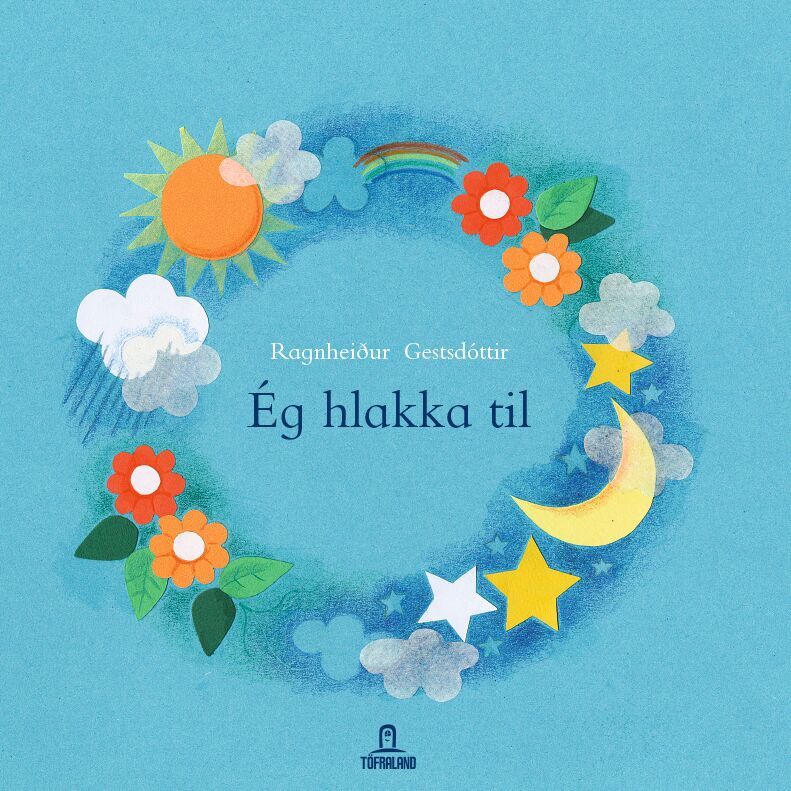

Ég hlakka til / Mig langar (I Look Forward / I Want)

Read more

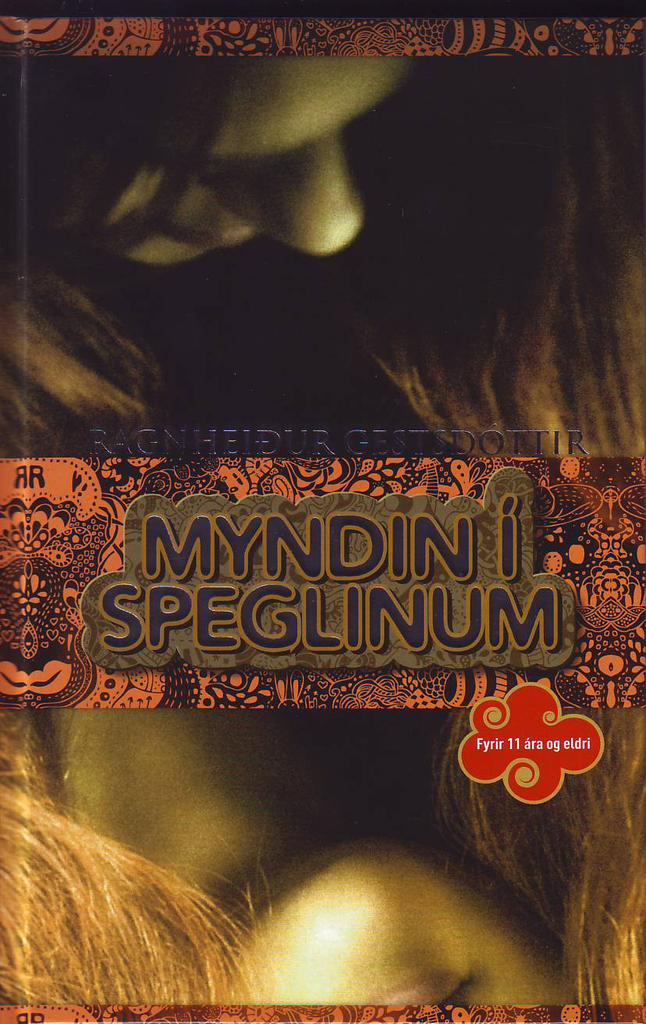

Myndin í speglinum (The Mirror Image)

Read more

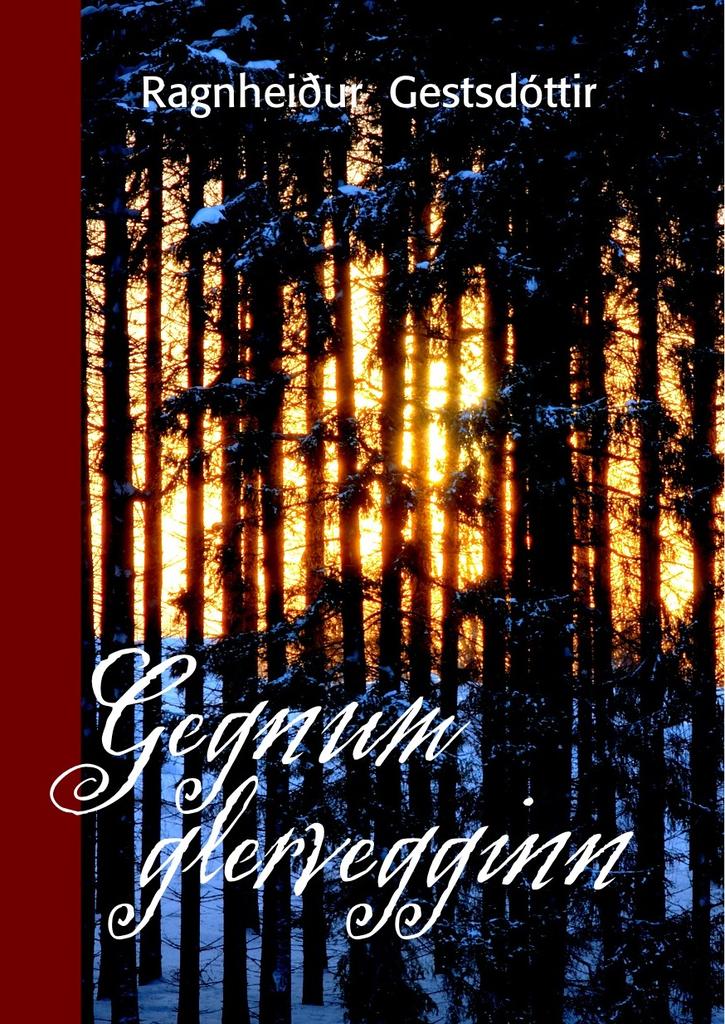

Gegnum glervegginn (Through the Glass Wall)

Read more