Bio

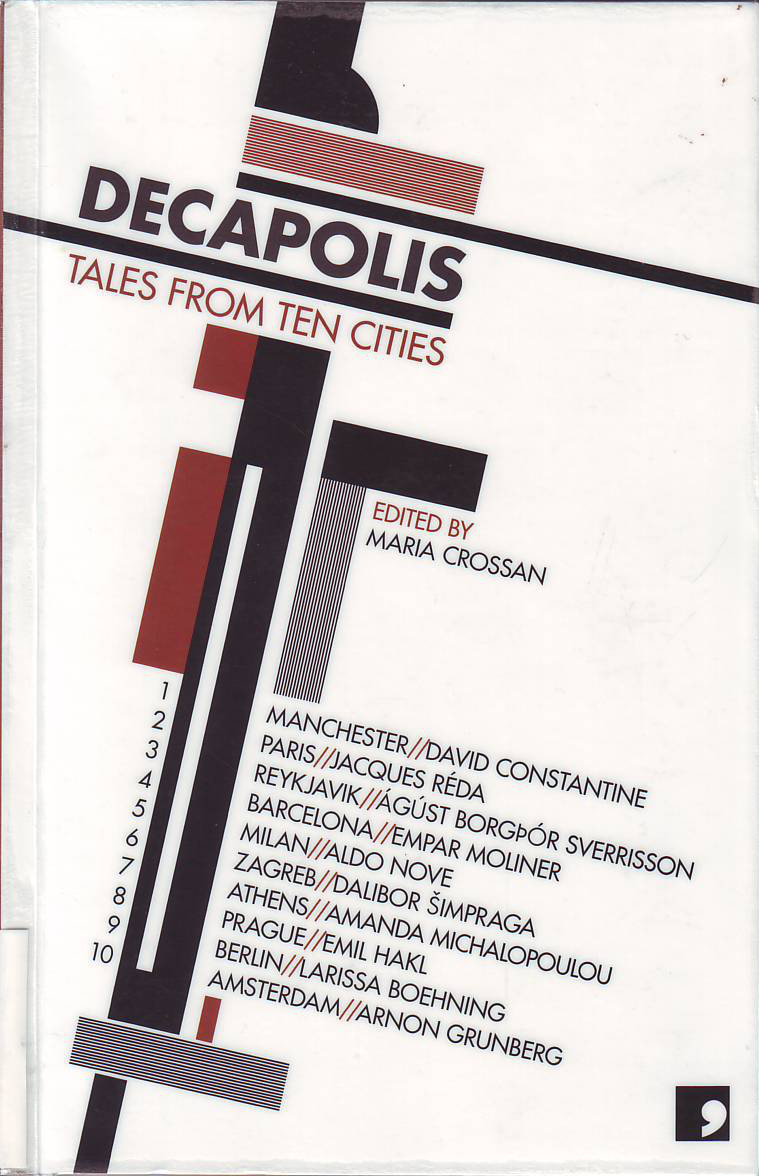

Ágúst Borþór Sverrisson was born in the west part of Reykjavík on November 19, 1962 and lived there until the age of 18. He finished his highschool education in Reykjavík in 1983 and then studied German and literature for one winter in Berlin and another one in Munich. From 1990 - 1992 he was a student of philosophy at the University of Iceland.

Ágúst Borgþór has for the most part worked in the field of writing, as a journalist and in advertisement and translation, among other things. He has also taught creative writing in Reykjavík.

Ágúst Borgþór is first and foremost a short story and novella writer. His first stories were published in his high school magazine, M.R., and in 1987 his story "Saknað" (Missing) was published in the literary magazine TMM. He was at the time working on his first short story collection, and the poetry book Eftirlýst augnablik (Wanted Moments). He has sent forward a few collections of short stories and his stories have also appeared in magazines and collections. Ágúst Borgþór has also sent forward novellas, the first one was Hliðarspor (Side-Track) in 2007. In addition to his fiction writing, Ágúst was a productive blog-writer for years, and has as such published numerous articles and essays on different issues.

From the Author

From Ágúst Borgþór Sverrisson

Already in my early childhood I dreamt of being able to create myself the very things that fascinated me. Football, movies and chess were among those things. These were far-fetched dreams and nothing more.

However, when my interest in literature was awakened for real when I was about 16 years old, I for some reason became convinced that I could write. When, about this time, I immersed myself in Þórbergur [Þórðarson] and Laxness for the first time, I was in fact as far from being able to make any literature as I was from making my former dreams of glory come true. Yet I was quite convinced and have been ever since. There were two reasons for this. The less decisive one being, that while I was always hopeless at football, showed little in the way of musical talent and was no good at chess (I leave the movies out of this, in fact my interest in them disappeared as soon a my interest in literature was awakened), I became early on quite adept at writing. A more decisive factor was that my literary desire was of a very different nature than other youthful daydreams, it ran much deeper and in some way that I cannot explain, was tied up with all other lust for life and happiness in my heart.

A fine writer once wrote in a newspaper article that vanity follows creativity like a shadow. The vanity of artists exists no doubt in various degrees, but it is clear that the desire to see one''s name in a respectable context in the papers, see a story by oneself in print or as a book on a shop counter, plays a part in the drive and stamina necessary to finish a presentable work of fiction. It is sometimes hard to see where the creative urge ends and vanity begins. The need to write always seems as deep-rooted, honest and free from worldly concerns, but most of the time when a work is written it is with the expectation of a publication or a publication timeline in mind and worldly ambitions become indistinguishable from the need for expression.

I assume that most people are inclined to look at the present moment of their lives as a certain watershed. I now feel that this has happened in my writing career when I think of the five short story collections behind me, books that have a great deal of things in common. These are close to 50 published short stories, which a handful of readers have been so endearingly clever in gathering a consistent world of narrative and meaning from. I feel that a certain period in my career has ended and although my next books will no doubt bear the trademarks of my earlier works, certain themes will not be revisited.

And now, when I think that a new chapter in my writing history is beginning, I sometimes ask myself why I write. In other words: Why do I spend my spare time writing? The answers are no longer as grandiose as in the beginning, when I did not know anything and was filled with romantic arrogance and high ideas. I am past forty and in many ways I live a comfortable life, although it can get a bit hectic at times. I have a good job, a good family, security and a fairly secure income. I am probably at the peak of my life and know that in ten years or so, some of my energy will start to wane. I am fully aware that the world will remain unaffected by whether I write more books or not. It could well be argued that it makes very little difference if I will or not. I could spend the energy that goes into writing and thinking about fiction on something else: for instance finding an ever better job or a more lucrative second job and become wealthier. I could also learn to play an instrument, join a hobby band and play my favourite songs.

Nowadays I sometimes say to myself and others that I write so that I will not have to build sun terraces and wind fences. My friend showed me the other day the results of his extensive labour in the yard. He had, both with his own hands and with the help of builders, constructed a beautiful sun terrace, a wind fence and a hot tub in his yard. I was happy for him but at the same time I inwardly cringed at the thought of spending my own time on such slavery, not to mention how far I am from having sufficient practical skills for something like this. I can not say with any conviction that my books are more remarkable than my friend''s sun terrace and wind fence. He would in fact be proven wrong if he tried to maintain the opposite and the silly debate would end in a draw.

Still I know that I am better suited for writing work than for wood work. Above all I want to spend this short life on things that I find interesting. There are people who look forward to reading more books by me. Their numbers are even rising slightly. I know that they would rather have me in front of the computer than in some insane pursuit beyond my capabilities, which I would have no interest in anyway. They want to be able to read a story by me while they rest on their sun terrace. These good people will get their wish.

Ágúst Borgþór Sverrisson, 2005.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

About the Author

Ingi Björn Guðnason: On the short stories of Ágúst Borgþór Sverrisson

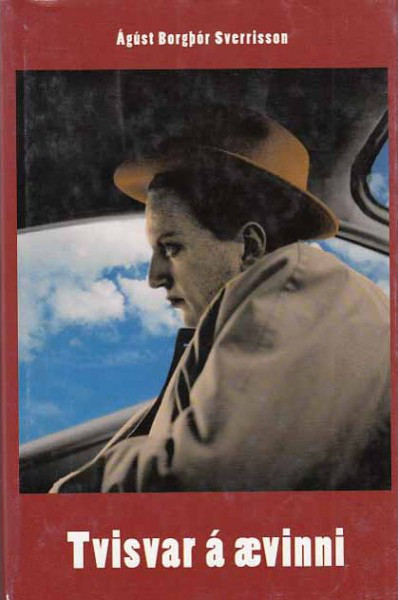

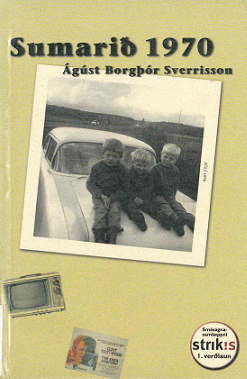

In his writings Ágúst Borgþór Sverrisson has almost exclusively focused on short story writing, with the exception of his first published work, the poetry book Eftirlýst augnablik (Wanted Moments, 1987). This poetry book was followed by five short story collections, published with fairly regular intervals, Síðasti bíllinn (The Last Car, 1988), Í síðasta sinn (For the Last Time, 1995), Hringstiginn (The Spiral Staircase, 1999), Sumarið 1970 (The Summer of 1970, 2001) and Tvisvar á ævinni (Twice in a Lifetime, 2004). By placing so much emphasis on the short story, he occupies a unique place within Icelandic literary context, as few authors have in recent years contributed so generously to short story writing.

As a literary form, the short story is not very old, at least not in the way we know it today, although its roots can certainly be traced back many centuries in short tales, such as myths and fairy tales. However, the short story is generally said to have come into its own as a modern literary form in the 19th century, when short, fictional stories began to change considerably. Roughly speaking, in the second half of the 19th century, the short story was starting to develop along two general lines. On the one hand there were stories with a traditional three-act structure similar to the one Aristotle had introduced in antiquity, i.e.; exposition of a situation, plot and resolution. This type is often associated with the short stories of the American Edgar Allan Poe and the Frenchman Guy de Maupassant. On the other hand there are stories which go directly against the traditional three act structure and seek instead to portray slices of life, in which mundane things and situations acquire a symbolic meaning, illuminating the bigger picture. This line is generally associated with the Russian author Anton Chechov, who had a massive influence on short story writing in the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. [For more about these two strands of the short story see e.g.: Rúnar Helgi Vignisson: "Eftirmáli", Uppspuni. Nýjar íslenskar smásögur ("Postscript", Fabrication. New Icelandic Short Stories), editor: Rúnar Helgi Vignisson, Reykjavík: Bjartur 2004, p. 14-149. Eileen Baldeshwiler: "The Lyric Short Story", The New Short Story Theories, editor: Charles E. May, Athens: Ohio University Press 1994, p. 231.]

Ágúst Borgþór´s short stories are clearly of the latter kind. In fact it can be said that his works, if viewed as a whole, addresses the diversity in everyday life. The extraordinary in the ordinary, a complicated simplicity in the lives of ordinary people. Simple, everyday things and problems are given a meaning that is not immediately obvious. Middle-aged men, young women, single mothers and children are the central characters in Ágúst Borgþór´s works. Ordinary people with mundane jobs; working in stock rooms, in canteens, in offices, as cleaners or drivers. Sometimes these characters have gotten the short end of the stick, in one way or another, and therefore Ágúst Borgþór´s stories can also to some extent be read in context with the so-called underdog motif which has long been common in short stories. It may sound as if they are lacking in conflict, even dull; however, in stories such as this the tension does not rely on the traditional three act method of storytelling, as mentioned earlier; but lies under the surface, even in the monotone and dullness of everyday life.

Ágúst Borgþór´s stories contain images, tiny fragments from the lives of the characters, which define them, even for life. Flashes from the past and from childhood are revealed in the context of events taking place the present. Sometimes the past and the present collide violently as if they were two different worlds. The story "Fyrsti dagur fjórðu viku" ("The First Day of Week Four") from the collection Tvisvar á ævinni (2004) is about an unemployed man who is looking for work. The man has been forced to sell his car and therefore has to travel on a bus. At first glance this may not seem like a very big deal. But in the figure of the bus, many fragments from the man´s life, both past and present, come together:

The last time he used a bus to get around, the cars were green. Back then they were also crammed with passengers, people on their way to and from work, students, elegant ladies. Sometimes the air in the cars was heavy with the smell of fish because of the fish factory workers who have now long since vanished from the city. Now it is like stepping into a less travelled parallel reality: inside the car are three Orientals and a young man having a loud conversation with himself (p. 19-20).

This description of the man´s experience of the bus ride reveals many things connected to the man´s own life, his position in society and the changes that have taken place within the society. All this is reflected in the buses, and their changed role becomes symbolic for the man´s position. The buses are no longer a space to encounter people from different parts of society, but instead belong in the world of society´s outcasts. This world was invisible to the man before he landed there unexpectedly after losing his job. The world that he encounters on the bus also jars with the past. The fish factories that have disappeared from the city and the unemployed man are placed side by side; both are obsolete. One could call this typical for Ágúst Borgþór´s method of storytelling, that is how he uses simple everyday things, like buses and fish factories, instead of thorough descriptions, to illustrate the characters´ position and state of mind. At the same time he shows us the bigger picture, i.e. society.

The main flaw in Ágúst Borgþór´s works, until now at least, has been repetition when it comes to the handling of the material and the style. The everyday themes described earlier run through all his works and the same can be said about the style that Ágúst adopted from his first short story collection and onwards. As a result, the stories and the characters in them all have similar characteristics. Contradictory as it may sound, the repetitive handling of material and style are also the strongest points in his works. Firstly, it is because Ágúst Borgþór has mastered quite well a simple, quiet and direct style which is more about showing than telling. A style that has become more polished and sophisticated with each new work and is also generally well suited to the subject matters of the stories. This can be seen in his last two works, Sumarið 1970 and Tvisvar á ævinni; in which Ágúst Borgþór can be said to have mastered the style that he has kept from his first short story collection and onwards. Secondly this flaw becomes a positive in quite a different way which makes Ágúst Borgþór´s works so exciting. Essentially, it has to do with the reading experience and the effect that the works have, both when looking at each work for itself, but also when looking at his works as a whole. It becomes apparent that the work hang together by a stronger glue than merely a polished and fluid style.

As the mood, situations and characters remain similar, both within individual works as well as in his oeuvre as a whole, one starts to feel that the stories are linked in some tangible way. That a character, a place or a family from one story actually appears in another story as well. In this way the stories in each book provoke mental associations for the reader. For instance one wonders of the boy in the story "Mánudagur" ("Monday") and the young man in the story "Batavegur" ("Recovery"), who both appeared in the book Í síðasta sinn (For the Last Time, 1995), are the same character at different ages. They certainly have various things in common, a father who drinks and an obesity problem, that they have experienced in a similar way as children. The boy in "Mánudagur" describes the bullying that he suffered because of his obesity in the following way: "More common though were comments about my figure, and although most people were tired of teasing me, I could still hear them" (p. 41). After this, it is as if the young man in "Batavegur" finishes the story: "The kids stopped teasing me. They teased me when I was "only fat." Then it seemed that I had become too fat to be teased" (p. 70).

Such an interconnection prompts the reader to think about the other stories in the book. The connection does not have to be too obvious; the mood and the situation of the characters are enough to arouse suspicion. Whether such suspicion is logical or not, it has the effect of making the stories complement each other, mental associations are formed, demanding a re-evaluation that causes each story to add something and throw a light onto other stories. The stories therefore work within a common context, the world of meaning of a particular story reaches out of itself and into other stories in the book.

Short story collections that form a strong whole, for example because all the stories happen in the same place and period or deal with the same themes, are often called short story cycles. To a certain extent, such works have both the characteristics of the novel and the short story collection. This is because they have the general feel of the novel, yet at the same time each story can stand on its own as an independent work. Works like this are therefore located somewhere between a short story collection and a novel. In fact the difference between short story cycles and "normal" short story collections is not clear, and perhaps most short story collections have some cyclical tendencies. I find this in all of Ágúst Borgþór´s works. In one of his works this tendency is perhaps particularly obvious. The book in question is Sumarið 1970 (2001), where the internal relationship between the stories is framed in such a way that a particular period (the seventies) serves as a sounding board for all the stories.

There are however, as I mentioned earlier, also strong links between stories that belong to different works, links that are clearer and more tactile than those that connect stories within individual works. To illustrate, it is worth looking at one example of a continuous thread that runs through three of Ágúst´s works. This is the story of the brothers Ólafur and Oddur who last appeared in the story "Sektarskipti" ("Blame Reversal") in the book Tvisvar á ævinni (2004). It begins with a few words that are symbolic for the thread that the story of the two brothers forms within his works as a whole: "The story about the good and the bad brother comes in many forms, both in fiction and in life. Often however, it is not about goodness and evil but about an unfortunate brother and a fortunate brother" (p. 49). One guesses that the narrator is suggesting that the story of Ólafur and Oddur is not being told here for the first time when he says that the story about the good and the bad brother "comes in many forms." When "Sektarskipti" begins, the brothers are grown up men, one is fortunate but the other is unfortunate. They first appeared in another of Ágúst´s short story collection, Í síðasta sinn, which came out in 1995, as young boys in a story which is titled "Rökkrið" ("The Darkness"). Next they feature, for the first time as adults, in the story "Viðvaningar" ("Novices") in the collection Hringstiginn from 1999. All the stories are all told from the point of view of the younger brother, Ólafur, and the older one, Oddur, is a secondary character.

The first story, "Rökkrið", offers a glimpse into what the future might hold for the brothers. Ólafur is younger and better behaved but at the same time more insecure, he looks up to Oddur and envies him for the attention he receives from their parents because of his various pranks. In particular, Ólafur´s envy is directed at the attention that the father gives to Oddur:

[...] when dad was not away from the home or preoccupied in his tool rental shop, he was telling Oddur off. Because Oddur was always acting up. Ólafur had stopped paying attention to what those misdemeanours were because they were so frequent and a constant conversation issue; there was incessant scolding. Ólafur was always never told off. Yet he was always afraid of provoking anger. It was a much more terrifying prospect to be told off when it had almost never happened. (p. 114)

In the story Ólafur is closer to his mother. They take walks together, where she tells him stories from when she was little, but despite this, she is distant: "Her mood was light but when they approached our house she went silent and her face became sad" (p. 114). The child´s perspective dominates here, he is not equipped to figure out why the mother becomes sad when they approach the house. But the reader can read about it between the lines and this foreshadows the events that follow. Distant parents and a lack of intimate communication with their children is in fact one of the main themes of Ágúst´s stories about children where an imminent divorce and other family problems are kept secret from the children. These stories are told from the viewpoint of the child, who has difficulty figuring out what is happening, as the father has suddenly, or gradually, simply moved out of the home into some room in another part of town. This is the case in the first story about Ólafur and Oddur, where the father gradually disappears from the home and a new man takes his place: "The changes descended like the afternoon darkness that he could never catch out. Without him noticing it, dad´s taxicab had changed from a car that he often sat in, into a car that he was always waiting for to return home" (p. 118).

If this story is seen as a sort of a prelude to the troubles that the "good" and the "bad" brother will be burdened by in the later stories, it explains the positions they will find themselves in as grown-up individuals. Oddur never manages to improve his reputation and can never wash off the troublemaker stigma of his youth, and gradually moves further down the path to misfortune. Ólafur´s outsider status in the family life and his position as a model child is a possible explanation for his cowardice as an adult and a hidden need to get attention for his wrongdoings like his big brother: "Mum talked to him more than his dad. Dad said he was a good kid and patted him on the head. "Try to be good, like your little brother," he said to Oddur" (p. 114).

In the story "Viðvaningar", which appeared in the book Hringstiginn (1999), the brothers are still following in the same track that they set out on as children. The events of the story undeniably bring to mind the opening words in the last story about the brothers that I quoted here in the beginning, i.e. that the story of the good brother and the bad brother is "not about goodness and evil, but about an unfortunate brother and a fortunate one." Still, the misfortune and fortune are double-edged, because their different positions in society are precarious. The goodness that Ólafu , the fortunate one, represents, is marked by hypocrisy. This is evident from the way he admonishes his brother for descending into a life of drink with a group of questionable people but is at the same time having an affair with a woman from the same circles. Interestingly, the story "Sektarskipti" could well be a direct sequel to the story "Viðvaningar", as it also revolves around Ólafur´s adultery and the brothers´ relationship and the reversal of their usual roles and their blame.

There are more examples of such serial stories between books. Some of Ágúst Borgþór´s best stories form a cycle of stories that are interconnected in more varied ways than the stories of Ólafur and Oddur. In its entirety, this cycle tells the story of a family who loses a son to illness. In this family´s story the stories are actually told from different viewpoints, on one hand a child´s and on the other the mother´s. Additionally, it seems that a secondary character from the first short story, who is the narrator of this family´s story, has his own story told in another place. The family story begins with "Hjónaherbergið" ("The Master Bedroom") in the collection Í síðasta sinn, where the remaining brother of the boy who dies is the centre of consciousness in the story, which is told in the third person narrative. The family story then continues through the story "Sjúkrabíll" ("An Ambulance") in the book Hringstiginn. It is told from the viewpoint of the mother in third person and describes her relationship with her remaining son. The last piece in this family history is the story "Hverfa útí heiminn" ("Disappearing Out into the World") in the book Sumarið 1970, where the life of the remaining brother is told in broad strokes and the story is his first person narrative. The family history is interesting for the fact that it does not exactly tell a story of a tragedy, i.e. the death of a child, but of the repercussions of this tragedy – the mother and son´s battle with grief in their daily life. A possible side story that I mentioned earlier is then the story "Framtíð drengs" ("A Boy´s Future") in Hringstiginn, which tells two parallel stories of the childhood and adulthood of a man who drives a bus and has bought a flat in the Breiðholt-neighbourhood. His circumstances are so similar to the tenant of the master bedroom in the story "Hjónaherbergið" that it is impossible not to connect them; he also drives a bus and has recently bought a flat in Breiðholt. The story of this man also echoes the family story, as it is about a boy who somehow loses his mother and the effect it has on him as a grown-up.

As we can see from these examples, Ágúst Borgþór´s works may perhaps be likened to a web which ties together fragments, forming a unified world. Sometimes the threads between the fragments are easily visible but sometimes they are not so obvious. But there is a sense that there is a general picture here, and as a result one feels that there is a continuity of meaning in the world of his stories.

© Ingi Björn Guðnason, 2005.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Awards

2001 - First prize in a short story competition on Strik.is: For the story Hverfa út í heiminn (the story was published in the book Sumarið 1970)

2000 - A competition hosted by MENOR and Dagur newspaper: Bænheyrður (a story from the book Sumarið 1970)

1994 - The Icelandic Broadcasting Service´s (RUV) short story competition: Recognicion for the story Fljótið (from the book Í síðasta sinn)

Afleiðingar (Consequences)

Read more

Inn í myrkrið (Into the Darkness)

Read more

Stolnar stundir (Stolen Hours)

Read more

Twice in a Lifetime

Read more

Hliðarspor (Side Steps)

Read more

The First Day of the Fourth Week

Read more

Tvisvar á ævinni (Twice in a Lifetime)

Read moreFyrsti dagur fjórðu viku

Read more

Sumarið 1970 (The Summer of 1970)

Read more