Bio

Friðrik Erlingsson was born in Reykjavík on March 4, 1962. He graduated as a graphic designer from the Iceland Art and Craft School in 1983.

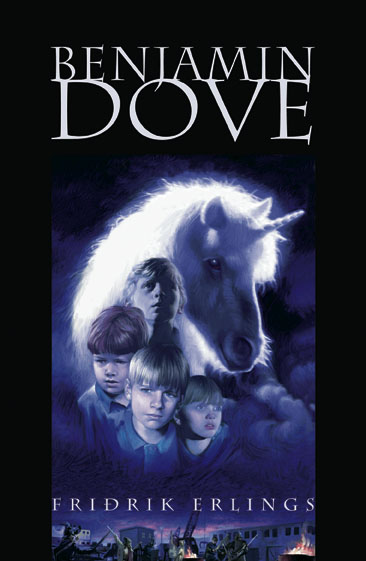

Friðrik Erlingsson has written and translated numerous lyrics, written scripts for film and television, as well as biographies and fictional work for people of all ages. His novel, Benjamín dúfa (Benjamin Dove) that depicts the world of a group of young boys in Reykjavík in the latter half of the twentieth century was published to acclaim in 1992. The book received numerous awards and has been translated to other languages. A movie based on the book was also well received in Iceland and abroad. An American movie has also been based on the book, Benji the Dove (2017). Friðrik wrote the script for the animated film Litla lirfan ljóta (The Ugly Caterpillar) which premiered in Reykjavík in August 2002 and he also wrote the script for the movie Þór - hetjur Valhallar (Thor - Heroes of Valhalla), which is based on his own book.

Friðrik has been awarded for his work, such as receiving the Reykjavík City Children's Literature Prize in 2002 for his translation of Mona Nilsson-Brattström's book, Tsatsiki og mútta (Tsatsiki och Morsan) and a nomination to the Icelandic Theatre Awards Gríman for his script and libretto for the opera Ragnheiður. A concert performance of the opera won the Icelandic Music Awards in 2013 as the music event of the year.

About the Author

At the Crossroads of Childhood: On the works of Friðrik Erlingsson

Friðrik Erlingsson’s oeuvre is quite varied. He has written lyrics to pop music, both original ones and translated from other languages. He has also translated books for children as well as writing fiction for children and grown ups, film scripts and biographies. He has also illustrated books by other authors. Although Friðrik’s works fall into different genres, a common thread can be found in most of them; they usually either depict children or are written for children, if not both. This is not only the case with his books for children or teenagers, Benjamín dúfa (Benjamin Dove, 1992) which was later adapted for the screen in Gísli Snær Erlingsson’s film, Afi minn í sveitinni (My Granddad in the Country, 1988) and Annað sumar hjá afa (Another Summer at Granddad’s, 1993), for his other novels also to a large extent tell the story of children. The protagonists in Bróðir Lúsifer (Brother Lucifer, 2000) and Góða ferð, Sveinn Ólafsson (Farewell, Sveinn Ólafsson, 1998) are children or teenagers. This is also true in Vetrareldur (Winter Fire, 1995) in the sense that the first part of the story describes the childhood and youth of the main character, Lilja. She is the only protagonist in these books that we follow into her adulthood.

The characters in Friðrik’s novels are usually outsiders in one way or another. Sveinn Ólafsson in Góða ferð, Sveinn Ólafsson (Farewell, Sveinn Ólafsson) is however quite a normal thirteen year old boy who suddenly decides to skip school to give himself some time to think about his life:

Auðvitað er allt satt í þessu bréfi; ég get ekki farið í skólann, það er sannleikur. Ég hvorki get né vil. Eina lygin er sú að það var ekki mamma sem skrifaði bréfið heldur ég. En það myndi heldur enginn taka mark á því sem ég segði svo þetta er eina leiðin sem ég hef til að kaupa mér frið, kaupa mér tíma til að hugsa málið. Það er allt og sumt. Kannski fer ég aftur í skólann einn góðan veðurdag og þá verður þetta bréf löngu gleymt og mamma mun ekkert um það vita. (119-120)

[Of course everything in this letter is true; I cannot go to school, that’s the truth. I neither can nor will. The only lie is that my mother didn’t write the letter, I did. But no one would take me seriously anyway, so this is the only way to get some peace, buy some time to think things over. That’s all. Maybe I will go back to school one day and then this letter will be long since forgotten and mom won’t know about it at all.]

Sveinn thus takes a break from society / school in order to find himself or some meaning in his life. At first, he intended to take his own life, but decides not to. The quote above shows that he does not intend to leave society once and for all, and in the end he does turn back. This is simply a conscious decision that he needs some time to find himself.

The characters in the novel Bróðir Lúsifer (Brother Lucifer) are almost all outsiders, but unlike Sveinn, they do not make a decision to stand outside society, they end up there for different reasons. The main character is the teenager Hinrik Vilhjálmur Ríkarður Karl, who always goes by the name Lúsifer because of his deformed looks. He lived with his mother when he was younger, wanting to be helpful and kind to her, but because he was constantly bullied and teased, he became more and more difficult to deal with and in the end she had to send him away. Because of his deformed looks and speech depravation, he stands outside society, whether it is in the city or at the farm he is sent to when his mother can’t take care of him anymore. Lúsifer wants to be a part of the group, he wants to be normal, and therefore he feels happy when someone talks to him:

Lúsífer haltraði á eftir þeim og var að hugsa um Skugga sem hafði komið til hans og talað við hann eins og venjulegan mann, spurt hvað væri austur og hvað norður. Það var góð tilfinning að hafa getað svarað honum næstum hiklaust. Það var líka gaman að vita eitthvað sem Skuggi vissi ekki; hann hafði spurt eins og þetta væri leyndarmál sem þeir áttu saman, Skuggi og Lúsífer. (26)

[Lúsifer limped behind them, thinking about Skuggi who had come up to him and talked to him like a normal person, asked where east was and where north. Being able to answer without almost any hesitation had made him feel good. It was also good to know something that Skuggi didn’t know; he had asked as if this was a secret they shared, Skuggi and Lúsifer.]

This feeling however never lasts long, and Lúsifer becomes more and more difficult with every new disappointment. The desire to be a part of the group is not limited to Lúsifer, almost all the character’s in the story share this feeling. The story takes part at a farm in a place that goes by the name Helvíti (Hell), a place that none of the characters wants to be in. They have ended up there, not by choice, but by some course of events and they seemed to be doomed to stay there forever.

It can be debated whether Lilja in the novel Vetrareldur (Winter Fire) chooses her own isolation or not, but she seems to want to be somewhere on the border. As a child, she is fond of the town drunk that no one else wants to talk to, and thus she seems to feel more connected to people who are outsiders than those on the inside. After she moves to Reykjavík, she becomes a ballet dancer and as such becomes a part of a society, which she later gets more and more isolated from after she falls ill. Even though she has a son, she could just as well not have any family, since he tries to avoid seeing her. People stop noticing her, and she become almost invisible. When she falls on ice close to the end of the story and breaks her leg, no one at all notices her:

Slydduflygsurnar hröpuðu letilega í kringum hana og yfir hana á meðan bílarnir brunuðu framhjá, ósýnilegri á milli skaflanna [. . .] Hún heyrði ógreinilegar raddir fólks á götunni, fótatak á gangstéttum en það virtist allt vera að fjarlægjast. (319-320)

[Wet snowflakes were falling lazily around her and on top of her while the cars raced by, invisible in between piles of snow [...] She could hear vague voices of people from the street, footsteps on sidewalks but all seemed to be fading.]

Lilja lies in a pile of snow in the middle of the city, but she could just as well be out in nowhere, since no one sees her. It isn’t until hours after she falls that Tómas notices her, but it is left unresolved whether she will survive or not.

Friðrik’s children’s books do not depict the same isolation. The stories Afi minn í sveitinni (My Granddad in the country) and Annað sumar hjá afa (Another Summer with Granddad) tell of a little boy who visits his grandfather in the countryside during his summer vacation. They are not outside society; they are just out in the country and very happy with that. The place is thus very far from the “Hell” Lúsifer has to live in. The boy and his grandfather feel good together, partly because they are in many ways alike. The boy, who tells the story, for example says this about his grandfather in Annað sumar hjá afa: “He in fact was a prankster and a bit of a kid inside.” (6)

Benjamín dúfa (Benjamin Dove) tells the story of a group of boys who form an order of knights to fight against injustice and for justice. They demarcate their space, people come and watch them fight with wooden swords, and they are firmly situated within the society they are a part of. They in fact become heroes in their community and the centre of it when they start collecting money for Guðlaug, an old lady who has lost her home in a fire. The people in the community become closer to one another as a result of this, as they all put their effort into helping Guðlaug. This becomes quite clear when Guðlaug moves into the new house raised for her after the collection:

Aftur var klappað og hrópað: Riddarar - riddarar - riddarar! Allt í einu fann ég hendur grípa um mittið á mér og okkur Róland og Balda var lyft upp og við bornir í gegnum hópinn til Guðlaugar. Hún faðmaði okkur að sér hvern á fætur öðrum, hló og brosti og grét en gat ekkert sagt nema: Elsku strákarnir mínir . . . elsku kallarnir mínir. (100-101)

[Again people clapped and shouted: Knights – knights – knights! Suddenly, I could feel hands gripping my waist and I was lifted up, together with Roland and Baldi, and we were carried through the crowd towards Guðlaug. She hugged each of us, laughed and smiled and cried but could say nothing but: My dear boys.... my dear lads.]

One of the things that connect Benjamín dúfa to Friðrik’s other novels is how close death is. Guðlaug’s cat is killed and this leads the boys to take matters into their own hands and revenge him, as is fit for true knights. Later, one of the boys, Baldur, is killed by accident when the knight’s game becomes too real. Changes always follow death, The Order of the Red Dragon is formed after the cat is killed, and it is dissolved after Baldur’s death.

In the same way, changes follow death in Vetrareldur and Bróðir Lúsifer. It can for example be pointed out that Lilja and her mother move after Lilja’s father dies, and this turns out to overturn her life. Similar changes can also be found in the lives of the characters in Bróðir Lúsifer. This death theme is however not to be found in Góða ferð, Sveinn Ólafsson. Death is also in a way close at hand in Annað sumar hjá afa, where granddad and the boy find a baby seal caught in a net when they are fishing. When granddad takes the seal out of the net, he is unconscious, but he manages to revive him. Thus, death is a threat here, although the life in this case is that of an animal.

One can find something that threatens life or health in almost all of Friðrik’s books, even in the children’s book Króna og Króni í Smáralandi (2000) where the title characters are on the run from the terrible Spender. The book is supposed to teach children to save their money and here humans are not in danger, just as in Annað sumar hjá afa. Benjamín dúfa is the only one of Friðrik’s children’s books where human life is threatened. In his other novels, threat is not only in the form of death, often the characters are threatened by some kind of an inner danger; they are dealing with some kind of a psychological turmoil. They for example all share the tendency to isolate themselves from other people, or be isolated from them for different reasons.

It stands out how alone in the world many characters in Friðrik’s novel are. Lúsifer is not without a father, he in fact has three of them, but none of them has any contact with him. When his mother cannot deal with him any more, he is fostered by a couple in the countryside that takes in troubled children. His mother moves to Denmark and he is totally without family, left alone with strangers. This is not as prominent a theme in Friðrik’s other novels, Lúsifer is by far the most isolated of his characters. Lilja in Vetrareldur looses her father as a child, but both her parents are there at the start, in spite of her father’s recurrent absence. After his death, her mother starts to withdraw from her more and more, and finally dies. Lilja’s aunt takes her mother’s place and thus Lilja is not left totally alone, not until later. Both in Vetrareldur and Bróðir Lúsifer, the protagonists live with their single mothers. The same can be said about Góða ferð, Sveinn Ólafsson, although he is still in contact with his father after the parent’s divorce. The father doesn’t have much time to be with him, but he nevertheless exists.

In Friðrik’s children’s books, life is less complicated and the family is closer at hand. Baldur in Benjamín dúfa lives with his single mother, but the rest of the boys live with both parents. In the books about granddad and the boy, both his parents take him to his grandfather’s house in the countryside. Life is simple in these books, and it seems very unlikely the boy will loose his grip on life. Granddad is also always there to take care of him, should anything happen.

Life is a bit more complicated in Benjamín dúfa and the boys do loose their grip on life for a while after Baldur dies. Loosing one’s grip on life is a repeated theme in Friðrik’s work, as has been pointed out here. To a degree this always seems to relate to the characters’ childhoods in some way, and thus one could conclude by saying that the subject is the transition from childhood to adulthood and what happens on this way. The child has to let go of its childhood safety net in order to be able to stand on his or her own feet. The question is then, how well people do people succeed at this?

Hákon Gunnarsson, 2002.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature.

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, p. 600

On individual works

Benjamín Dúfa

Gintarè Adomaitytè: "Kas ten, gelmèse? Nejaugi audros? : zvilgssnis i Islandu vaikku literatûra"

Krantai: Meno kultûros zurnalas 2009, 1. tbl. bls. 39-41.

Bróðir Lúsífer

Isaacson, Lanae Hjortsvang: "Brodir Lusifer" (review)

World literature today 2002, no. 76: pp. 195

Hliðargötur

Isaacson, Lanae Hjortsvang: "Hliðargötur" (review)

World literature today 2002, no. 76, pp. 208

Ragnheiður

Ásta Andrésdóttir: "Skálholt's star-crossed lovers"

Iceland Review 2014, 52. árg., 2. tbl. bls. 10.

Awards

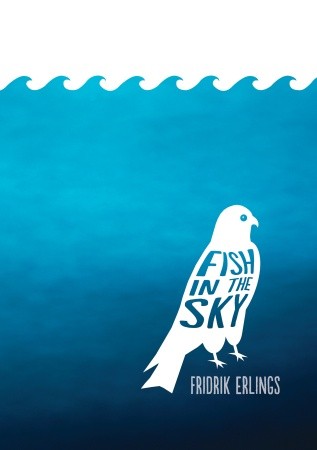

2010 - IBBY Honour List: Fish in the Sky (English translation of Góða ferð, Sveinn Ólafsson)

2002 - The Reykjavík Board of Education Children's Literature Award: Tsatsiki og Mútta by Mona Nilsson-Brännström (for his translation)

1993 - The Reykjavík School Board Children's Literature Award: Benjamín dúfa (Benjamin Dove)

1992 - The Icelandic Children's Literature Award: Benjamín dúfa

Nominations

1994 and 1995 - The Nordic Children's Literature Award: Benjamín dúfa

Benjamín dúfa (Benjamin Dove)

Read more

Þór: Leyndarmál guðanna (Thor: The Secret of the Gods)

Read moreBenjamin Dove (audio book)

Read more

Zalozba Grlica

Read more

Þór - Í Heljargreipum (Thor - In the Jaws of Hell)

Read more

Fish in the Sky

Read more

Benjamin Dove

Read more

Benjaminas Balandis

Read moreLa larva fea

Read more

Glæstar vonir (Great Expectations)

Read moreRómeó og Júlía (Romeo and Juliet)

Read more

Baskerville hundurinn (The Hound of the Baskervilles)

Read moreDrakúla (Dracula)

Read moreDrakúla – hljóðbók (Dracula – audiobook)

Read moreFýkur yfir hæðir (Wuthering Hights)

Read moreFýkur yfir hæðir - hljóðbók (Wuthering Hights - Audiobook)

Read moreInnrásin frá Mars (The War of the Worlds)

Read moreInnrásin frá Mars - hljóðbók (The War of the Worlds - Audiobook)

Read more