Bio

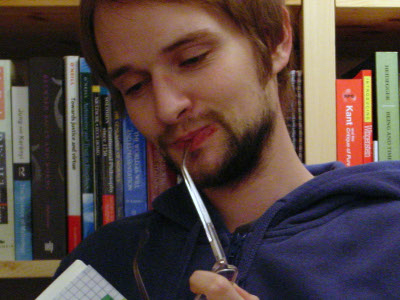

Óttar Martin Norðfjörð was born in Reykjavík on January 29, 1980. He studied philosophy at The University of Iceland, finishing his undergraduate studies in 2003 and his M.A. in 2005. In 2004 he was a philosophy student at The University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Óttar studied Spanish at Universidad de Sevilla in Spain in 2006 and has also read German in Heidelberg and French in Nice, as well as a little bit of Arabic in Iceland. He studied drawing at The Reykjavík School of Visual Art from 1998-1999.

Óttar has mostly worked in the field of writing. He worked for DV newspaper in 2006, editing its culture paper, writing literary reviews and translated a series of articles by Paulo Coelho. He has also been a pizza baker, worked in a book store, and been an assistant teacher at The University of Iceland as well as assisting one of the philosophy professors there from 2003-2006. He has written about philosophy for journals and websites and exhibited his art as well as designing t-shirts under the trade mark “Alive”. From 2004 Óttar has mostly worked at his own writing.

Óttar’s first published work is the poetry book Í Reykjavík (In Reykjavík) which he published himself in 2002. His first novel, Barnagælur (Child’s Play) was published in 2005. Since then, Óttar has written more books of poetry, some with his own illustrations and clip-art, published his poetry in magazines, collections and on the internet, a comic book and a number of novels, the most recent being Blóð hraustra manna (The Blood of Healthy Men) in 2013.

Óttar Martin Norðfjörð lives in Barcelona in Spain.

Publishers: Sögur útgáfa and Nýhil.

From the Author

From Óttar Martin

Words are like insects. Crawling in the dark. I remember when I wrote my first poem. I had no idea what I was doing. Covered in dirt. Picked up insects, one here, there another and glued them together. Pulled their feelers off or the head and hoped they would stick together. Just somehow. Why choose this word instead of some other? Why write about this rather than that?

It is crawling with life down here. This is not pretty. Rather disgusting, to tell the truth, but feels like home. I can’t explain why. Pink worms, beetles, spiders and even cockroaches if you will. Everything is mixed up and you in the middle with your mouth open, chew everything and spit it out and hope it does the trick. This is how I felt when writing my first poetry book. Completely lost in a flow of words and ideas. Having lost all directions. Is this funny? Should this be funny? Is this maybe too sentimental? Does it matter?

And before I know it, night has fallen. I therefore put on my helmet with the lantern my mom gave me and wait for the rain. Ready with the shovel and the blue bucket. Wait. Then I hear the first drop fall. Hear this familiar sound when the rain hits the leaves and the sod. I run out into the garden and start digging and digging. Smile in anticipation. The insects run like crazy when their shelter disappears. Suddenly defenceless on the lawn. My wet fingers carefully pick them up from the ground and put them in the blue bucket. This is how I spend the night. Collecting wriggling insects. Slimy. I accidentally crush some that die instantly. Catch others. When the bucket is full I return inside. Soaking wet and tired, but content. Enough supplies in the crop for the next day.

Óttar M. Norðfjörð, 2007.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

BARBEQUING IN THE DEAD OF WINTER

In 2005 the poetry group Nýhil published a collection of love poems called Ást æða varps1. Óttar Martin Norðfjörð wrote a few poems for the collection, where he states and restates his love for his girlfriend. The second poem is a description of the precise moment the speaker fell in love, that exact point in time where love springs forth and a man is changed forever – as tradition dictates:

Þegar þú

settir typpið mitt

uppí munninn þinn

gastu sett það

dýpra

og lengra

en allar hinar.Miklu dýpra

en ég hafði áður séð.Miklu dýpra

en ég gat ímyndað mér

að hægt væri.Ég vildi vera þarna alla ævi.

Þú horfðir í augun mín.

Ég horfði í augun þín.Ég varð ástfanginn.

[When you

put my dick

in your mouth

you could take it

deeper

and farther

than all the others.A lot deeper

than I had seen before.A lot deeper

than I could have imagined

possible.I wanted to be there forever.

You looked me in the eyes.

I looked you in the eyes.I fell in love.]

Two lovers gaze into each other’s eyes and a spark of love is struck between them. One can hardly imagine a more romantic motif, but in this case love is ignited by a record-braking blowjob, a feat more likely seen in a porno than a sonnet. Óttar’s other poems strike a similar chord: The poet reiterates its love by threatening to beat up his girlfriend’s previous boyfriends, studying the clots of blood in the toilet when she’s having her period and suggesting that they try “all sorts of new things“ with each other’s butts. These are love poems where love is an extension of self-obsession and romance is spun from violence and pornography. At the same time the poems are both subtly funny and sincere. It’s as though the reader is eavesdropping on an awkward soul who stands under a balcony, shouting serenades. He’s vulgar and reeling and more than a little ridiculous, but there’s not doubt in your mind that he means every word.

Óttar often walks a thin line between sincerity and sarcasm in his works, clouding the irony and reveling in dark humor. The most vivid example of this is his second book of poetry, Grillveður í október (Barbeque-Weather in October, 2004), where the humor is downright revolting, and the filth and violence is sometimes so overwhelming that one has to ask whether it’s even okay to laugh at all. One of the poems describes the seven o’clock news:

Á sjöttu hæð háhýsisins, í bás 120-C, fékk

viðskiptafræðingur að nafni Böðvar loks meira

en nóg og skaut þrjá samstarfsfélaga sína til

bana og svo sjálfan sig í hausinn. Eiginkona

Böðvars, hún Klara, fylgdist með manninum

sínum í beinni útsendingu á stöð 2. Aldraðir

foreldrar Böðvars sáu svo son sinn í

endursýningum kvöldfréttanna, rétt áður en

fréttamaðurinn tilkynnti að úti væri fyrirtaks

grillveður og það í október, góðir Íslendingar![On the sixth floor of the high-rise, in cubicle 120-C, the

business administrator Böðvar finally had more than

enough and shot and killed three of his co-workers

and then shot himself in the head. His wife,

Klara, watched her husband

live on channel 2. Böðvar’s elderly

parents saw their son on

the rerun of the nightly news, just before

the weatherman declared the weather outside perfect

for barbequing, and in October no less, my fellow Icelanders!]

Here we have the title of the book as well as the thread which runs through the book’s social critique: All around us there are tragic news reports and boundless trash-journalism, and that’s all fine and dandy, but what ultimately matters is whether it’ll stay warm enough to barbeque through the weekend. Descriptions of gang rapes lead to ads for text message-games from car dealerships, and while the Twin Towers collapse the speaker can’t stop thinking about eating his own snot. This theme is repeated in the book, along with short stanzas on rapists, racists, murderers and pedophiles, as if to underline the horrible state the world is in, and how the apathetic bourgeoisie maintain the status quo. The style is cold and plain, and the subject matter is captivating, but the poet doesn’t get its feet off the ground until the end of the book.

On the last pages the speaker throws himself into gear and spews forth a rolling diatribe which encapsulates the book, and also questions the act of writing and publishing such an “interesting and provocative book of poetry, that everyone should definitely check out”. Furthermore, it’s clear that the book won’t change anything, as “nothing changes, things just change shape and costume”. Thus the book itself is opened for discussion, but the poet would rather not take any credit for it: He apologizes to the reader, asks him to burn the book and so on, and states that he is in no way responsible for the content: “It is not I who write it but the world which feeds my head”. The poem is an ineffective portrayal of society, the poet is an intermediary who writes solely to “pick up chicks”, and so the point of reading the book must be to spend money on it and hope that the barbeque-weather holds through October, preferably into the spring. The cynicism is raging, and it’s thrown around both carelessly and with great contempt, resulting in the most uncomfortable kind of humorous poetry one would dare to recommend – regardless of the poet’s stated objections.

Despite the irony and the apathy so apparent in Grillveður, there is a sense that the book is a direct reaction to a malignant social condition. In Sirkus (Circus, 2005), Óttar’s third book of poetry, this condition is translated into a world-ending epidemic of insanity and leprosy. The book can roughly be divided into two parts: On the one hand there are descriptions of people who either fall apart or go mad and mutilate themselves with varying degrees of innovation. On the other hand there is the first-person account of the speaker from inside the bar Sirkus in downtown Reykjavík. Outside the sea-gulls pick apart the bodies lying by the edge of the road, but inside the masses drink and dance,

[...] sirkusdýrin svitna

og sprikla og klifra upp um alla veggi

garga eins og apar eða villikettir

glöð en hrædd sum detta niður dauð

afgangurinn dansar áfram

líkt og ekkert hafi í skorist

líkt og heilalaus zombí

blóðið spreyjast á borðið.[[...] the Circus animals sweat

and jump and climb the walls

scream like apes or wildcats

happy but scared some drop dead

the rest keep dancing

like nothing happened

like brainless zombies

the blood sprays across the table.]

It’s a party at the end of the world where everyone dies sooner or later, but in the meantime there’s plenty of life at the bar. Those who stay away from Sirkus die alone in their little corner of the world: Margrét eats herself to death in front of the TV; the high-fashion clad bourgeois woman drops her jaw on the floor; the bishop gouges out his own eyes, castrates himself and finally commits suicide in order to get into heaven; the Prime Minister goes crazy and masturbates during a live TV broadcast; and so on.2 The irony so prevalent in Grillveður is virtually non-existent in Sirkus, instead Óttar bluntly attacks various types of hypocrites, consumer-junkies and superficials, inventing a suitable death for each one.

Along with these grotesque descriptions of disease and death there are drawings by the author, illustrating the same. The effects of these illustrations vary considerably from one poem to another. In some cases the drawings add something to the text, either providing a new point of view or topping off the poem in a pictorial punch-line, as it were. This marring of the verbal and the pictorial produces some of the strongest poems in the book. But more often than not the drawings merely illustrate a detail from the text, which can be pleasing (or upsetting) to the eye, but doesn’t really do anything for the individual poems or the book as a whole. This is all but detrimental in poems such as “Djúpt ofan í Atlantshafi” (Deep in the Atlantic Ocean) or “Þegar allt verður eitt og meikar fullkomið sense” (When All Becomes One And Makes Perfect Sense), where the words flow in a stream of consciousness which seems better fit for a booming recital than quiet contemplation.

In Sirkus people die slow, agonizing deaths. The apocalypse foretold by countless prophets and lunatics throughout the ages has finally come about, and although each of the characters falls apart and decomposes in their own way, no one seems to think that the plague can be avoided or overcome. Those with the most stuff or the best god are just as doomed as everyone else. The circus animals that drop dead at the speaker’s feet seem to have the right idea: Since the end is inevitable, one might as well do a little dance and keep partying into oblivion. This theme of carefree response to inevitable doom is also present in Gleði og glötun (Joy and Damnation, 2005), but in a more stoic manner.

Joy and damnation and old is made new

Gleði og glötun is perhaps Óttar’s most accomplished book of poetry, because of the way in which it’s put together. The newspaper clippings and the handmade collage artwork are well suited to the immediacy of the poetry: This book discusses a society we know at the very moment of the book’s publication. However, the book also includes older newspaper clippings, for example a skin cream advertisement some would see as a reminder of a simpler time in advertising and media. But the paradox is this: What we print today rarely survives through the week, much less any longer than that. However, we must acknowledge that the content does survive by taking another form. New ads for skin cream supplant the old ones and the product keeps moving.

This is the tension between the form and content of Gleði og glötun. The handmade cut-up art and the handwritten poetry imply urgency, a message hastily delivered onto the street by means of pen, glue and photocopy, for there is no time to lose. The content of the poetry, however, is that we are already on the brink of apocalypse and that there’s no use trying to do anything about it now:

[...] láttu öllum illum látum,

ekkert af þessu skiptir neinu máli,

ekkert breytist, skildu það,

sama hvað þú gerir.[[...] raise hell,

none of this matters,

nothing changes, understand that,

no matter what you do.]

So the immediacy and the hurried handcraft must simply be a way to keep the poet and his readers entertained while the darkness sets in, a temporary source of joy in the face of eternal damnation.

It’s precisely this wacky fatalism which makes the book so entertaining. Óttar’s earlier works include a fair amount of irony and the grotesque, which can be very funny, but in Gleði og glötun he seems to be on a roll. Photos of Óttar crop up on more than one occasion, the poet acting like a host or main anchor, delivering messages such as “Óttar says: Why not give peace a chance?” or “Don’t forget religion, kids”. These kinds of exclamations are of course slathered with irony in book where war and destruction are endless and inevitable, and Hallgrímskirkja3 dispatches its zombies to feed on the people of Reykjavík.

The ironic imagery is also in direct opposition to the earnest handwritten poetry, where the politician, the activist/demonstrator and the poet are all addressed individually. To the demonstrator:

Farðu í kröfugöngu,

mótmæltu mismuni og ójafnrétti,

skapaðu stemmningu,

það skiptir engu máli [...][Join a march,

oppose inequality and injustice,

create an atmosphere,

it doesn’t matter. [...]]And to the poet:

Skrifaðu eitthvað ljótt,

vertu gagnrýninn, vertu harður,

finndu ádeiluna, það skiptir engu máli,

kallaðu Davíð svín,

það skiptir engu máli [...][Write something nasty,

be critical, be tough,

locate the critique, it doesn’t matter,

call Davíð4 a pig,

it doesn’t matter [...]]

But there is some spunk left in this particular poet. In the final pages of Gleði og glötun, he addresses the politician, and a line can clearly be drawn between it and Óttar’s first novel:

Þú talar og hljómar eins og hugsjónamaður,

þú talar hátt og hljómar

eins og uppreisnarmaður.Þú ferð fögrum orðum um framtíðina,

þar sem fólk er frjálst og hamingjusamt,

þú talar um vald og ok

og lausn undan kúgandi öflum.Þú fjallar um óréttlæti í heiminum,

óréttlæti sem nauðsynlegt er

að stöðva umsvifalaust.Þú ert drukkinn og sorglegur hræsnari,

sérðu það ekki?Á bak við orð þín býr draumur

sem þú heldur einungis

að þú viljir ná.Jú, þú kannt að tala um betri heim,

en þú býrð þar

og vilt ekki fórna honum.Þú segir orð sem eru falleg og innblásin,

en orðin verða dauð í lok kvöldsins

og gleymd á morgun

þegar nýr dagur hefst.[You speak like a visionary,

You speak loudly and sound

like a rebel.You speak well of the future,

where people are free and happy,

you speak of power and subjugation

and freedom from oppression.You speak of injustice in the world,

injustice which must be

stopped immediately.You are a drunken, pathetic hypocrite,

don’t you see?Behind your words there lies a dream

you only think

you want to reach.Yes, you can speak of a better world,

but that’s where you live

and you don’t want to give it up.You speak words that are beautiful and inspired,

but are dead by the evening

and forgotten tomorrow

when a new day dawns.]

Here the poet addresses a well-spoken hypocrite who could pretty much be anyone, but in the context of Gleði og glötun, which specifically discusses the hypocrisy and demon-like behavior of U.S. President Bush and the Icelandic Independence Party, one can safely assume that the words are meant for right-wing politicians. It’s “they” who speak of capitalism and globalization and “are always saying something”. In the novel Barnagælur5 (Child’s Play, 2005),published the same year as Gleði og glötun, the protagonist and storyteller is one of these people. But in Óttar’s writing there is no time for half-measures, and the aforementioned politician isn’t merely a self-promoting hypocrite, but a full-fledged monster.

Barnagælur is the story of Pétur B. Ásgeirsson, congressman and pedophile. Pétur played football with the right club, went to the right collage and studied law at the University of Iceland. He was student body president, ran for the University Student’s Council for the right-wing party and became the secretary of the junior division of the Independence Party (the right wing party and political domain of former Prime Minister Davíð Oddsson). He now has a seat in Alþingi (the national parliament), writes articles on design and lifestyle and supports five third-world children. He’s a handsome man with a great body (“Like Brad Pitt before he did Troy“), has a beautiful fiancée from a well-standing family and lives in a fabulous, tastefully decorated apartment in the right part of the city. That’s Pétur’s CV in a nutshell, a document in which he takes great pride, reading it from time to time for enjoyment and relaxation, and believing it to be “almost perfect“. He never explains exactly why his resume isn’t completely perfect, but most likely it’s because he lacks the law degree itself – as a character in the book hints, Pétur never actually graduated University.

As previously mentioned, Pétur is a pedophile. He’s also a racist, rapist, murderer and a cannibal, and in no way a likeable person. He sees his relationship with his fiancée and his friends as political strategy, and his day to day activities are structured in a way as to get his face in the media and collect more and more votes. He is careful to always tell people what they want to hear and tries his hardest to make friends with people he finds repulsive. There’s no indication, however, that Pétur has a long term plan – that he’s acquiring political and monetary capital to some great end. He likes the idea of being a famous politician, but hardly ever shows up to work except to suck up to his superiors and climb the social ladder. And so Barnagælur paints as cynical a picture of a politician as one is likely to see: A man who despises the people he’s meant to serve and seeks power for power’s sake.

That’s really the heart of the matter because at the core of Barnagælur lies a meditation on power. The only political bones of contention mentioned in the book are the so-called “Fjölmiðlafrumvarp”6 and the Iraqi war, but Pétur doesn’t seem to have an opinion on either one. What really matters to him is that his party’s stated objectives are met and that the country is bent under the will of himself and his colleagues. In a similar fashion, Pétur exerts his authority and has his way with very young girls, justifies his behavior to himself and the reader with the standard excuses of pedophiles (that the girls are asking for it, that they even seduce him), and at the same time describes how he leaves them behind battered and crying. The implication is not that (corrupt and arrogant) politicians are equal to pedophiles, but that they are both abusers of power. They both deliver themselves into positions of power with sugar and promises and then betray the trust of those least deserving in order to satisfy their own cravings and whims.

The book pushes the envelope in regards to descriptions of rapes, murder and cannibalism, but still doesn’t come close to its prime example, Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho (1991). Patrick Bateman, Ellis’ protagonist and storyteller, is the archetypical 90’s Wall Street yuppie. He’s one of the best and the brightest, the economical Hope of the States, able to do pretty much whatever he wants without having to worry about the consequences. The fact that Óttar should find a place for this kind of madness and social disconnect in the Icelandic halls of congress in 2004 speaks volumes about his view of Icelandic society in the beginning of the twenty-first century. It’s also interesting to note that at the end of the novel, where Óttar documents his “sources” (for example: “The email sent from Florian to Pétur is based on a web-page maintained by a self-declared pedophile.”) there is no mention of American Psycho, but the similarities are perhaps so numerous and clear that the author doesn’t see a reason to detail the connection specifically.

A stronger example of Óttar’s rewriting of another writer’s text can be found in Grillveður, where the poem “Mynd eftir barn“ (A Drawing by a Child), by Dagur Sigurðarson is reproduced, spellchecked, punctuated and named “Dagur“. The book also contains references to Tíminn og vatnið (Time and the Water, 1948) by Steinn Steinarr and The Waste Land (1922) by T.S. Eliot, but in this case Óttar appropriates the whole of Dagur’s poem. Just as with Barnagælur and American Psycho, no one should think that Óttar is stealing anything, that is, that he’s somehow trying to erase the earlier poem from memory and replacing it with his own. The spelling is corrected in order for the poem to align with the whole of Grillveður í október, but it is also a declaration on behalf of the poet: The poem which once belonged over there now belongs here. And without going into the specifics of how a poet slays his fathers it’s clear that Dagur is here named as a direct influence.

Furthermore, the text of the poem is changed only so slightly as to still be easily recognizable to those familiar with it, but misleading for those who are not as well read, establishing a set group of readers for Óttar’s grave robbery. (For example, the connection is not easily found by doing a google search of Óttar’s appropriated lines.) Finally, the original poem, “Mynd eftir barn“ is supposed to be a written adaptation of a child’s drawing, at least in name if nothing more. Dagur translates lines of pencil and chalk into words like “cat“ or “house“ but Óttar spellchecks the word “haings“ and changes it to “hangs“. Both poets ponder the virtue of these kinds of translations, each in their own way, but the answers to those questions lie outside the range of this discussion.

Still, it must be mentioned that Óttar, who has gone from Eliot to Steinn Steinarr and then to Dagur, tops off his tour by repeating his own poem, printing the one from page 9 again on page 29, and adding a “(e)“ to the title. This is recognized by practically everyone as the symbol for a rerun in the nation’s TV-guides, the Icelandic word for rerun being “endursýning“. Finally Óttar repeats the poem on page 15 of Grillveður í október in the shopping chapter of Barnagælur, where Pétur buys Óttar’s book of poetry and praises him for making fun of “chinks, sandniggers, immigrants and other pests of society“. Thus the author introduces himself to his character and, at the same time, makes fun of those who don’t appreciate the irony in his work. And apart from all that, this is of course a brilliant and playful advertisement for his book of poetry.

Abraham and all the rest

Kosningar (Elections, 2007) is a short novel, set in the months before the parliamentary elections of 2007 and published under the pen name T Thorvaldsen. Two members of the Icelandic legislative assembly, Hörður Grímsson of the independence party and Agnes Sverrisdóttir of the progressive party, have drunken sex in a men’s bathroom at the assembly’s last annual party of the term in Hótel Saga. Bjarni Ólafsson, from the liberal party, witnesses the act and tries to blackmail the couple to form a majority with his party, following the elections. In addition to this, Hörður’s wife Ósk is diagnosed with Chlamydia, which her husband picked up from a prostitute in Brussels while on official business for the government. A journalist named Ásdís (who herself has an affair with a married priest) gets mixed up in all this while doing research on public officials who buy sex while traveling on taxpayers’ money.

Kosningar is the first in a series of books named Íslendingar (Icelanders), and the second book, París (Paris), was published in the summer of 2007. On the back of Kosningar it says that with this series of books “we open a door to reveal the Icelanders, the nuevo-rich nation of the north.“ The sample of this nation taken by Kosningar is made up of shameless government servants, journalists without honor, corrupt clergy and a bum who begs for a bar of chocolate. The book resembles Barnagælur in that politicians are still very much corrupt (and members of the ruling parties get away with assault and battery) but now priests and members of the press are not to be trusted either. In Kosningar Óttar offers yet another cynical view of the pillars of the community, and does so very successfully.

There is a similar feeling to Jón Ásgeir og afmælisveislan (Jón Ásgeir and the Birthday Party, 2007). The characters include a host of national and international celebrities but the real targets this time are Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson (a very prominent Icelandic businessman) and his nemesis, former Prime Minister Davíð Oddson. In Barnagælur the latter (although the character is never actually called Davíð Oddsson) is liquored up and sent away with a stripper, only to be blackmailed by the narrator into stopping a murder investigation. In The Birthday Party Jón Ásgeir clones Davíð Oddsson and has the replica sing Happy Birthday to him on stage at his lavish birthday party, dressed in a formal gown and earrings. For this he solicits the help of Kári Stefánsson (director of deCODE, an Icelandic company in the business of genetic research and development), who is now a crazy scientist living in a spaceship which hovers over deCODE’s headquarters. Jón Ásgeir lives with his father (also a prominent businessman and founder of the empire over which Jón Ásgeir presides) in a castle by the harbor, with little pet piggies roaming around and big sacks of money in every corner – dollars and euros, of course.

Óttar still has his sights set firmly on the leaders of the community, but here the story and setting both are very fantastical and the attacks more playful than vicious. Jón Ásgeir og afmælisveislan mocks people who are already in the spotlight, and the book features actual pictures of the character’s heads, as if cut from the pages of newspapers or magazines.

The biography of Hannes Hólmsteinn Gissurarson7 strikes a similar chord, but we have now seen two of the planned three volumes, with the third presumably coming out before Christmas 2008. Hannes: Nóttin er blá, mamma (Hannes: The Night is Blue, Mother, 2006) and Hólmsteinn: Holaðu mig dropi, holaðu mig (Hólmsteinn: Weather Me, Drop, Weather Me, 2007) say precious nothing of Gissurarson’s life, but they are of course not meant to. The point is that anyone can write a biography of anyone else, but when Hannes: Nóttin er blá, mamma was published Gissurarson had just finished his three volume biography of the writer and Nobel laureate Halldór Kiljan Laxness, amid some general controversy and the disapproval of Laxness’ family. Óttar’s biography is a carefully constructed hack job in photocopy, which demonstrates that even though someone writes a well-intended biography of a national icon, that doesn’t necessarily mean that that someone can write worth a damn, has learned to indicate his sources or that he or she even knows anything about the person in question. The question then becomes why Óttar chose Hannes Hólmsteinn Gissurarson as his subject, and the reader is invited to ponder this at his or her leisure.

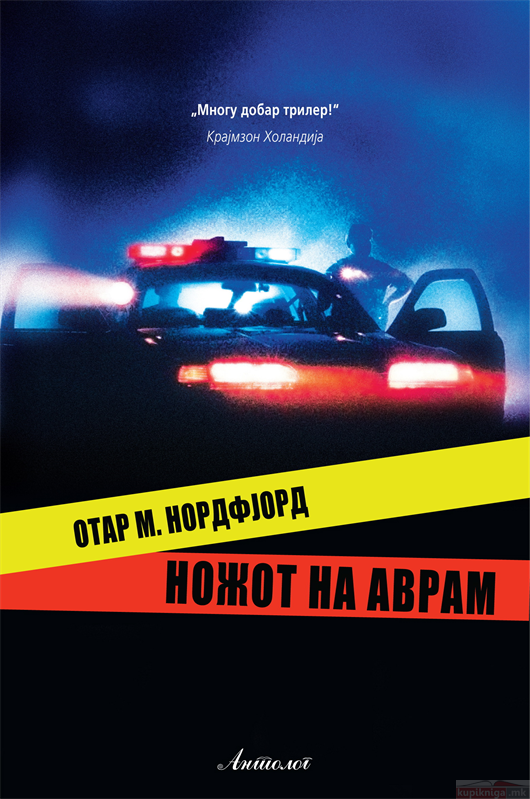

The homemade do-it-yourself look which is prominent in Jón Ásgeir og afmælisveislan and Gleði og glötun is elevated to a kind of idiot aesthetic in Hannes and Hólmsteinn. Óttar uses this style to indicate playfulness, fatalism and satire, all the while reminding the reader that the books are published with little or no money, and that a young poet, novelist or biographer doesn’t have to put him- or herself in debt in order to put his or her words out in public. In contrast, Hnífur Abrahams (Abraham’s Dagger, 2007), Óttar’s latest novel, is a good-looking, well crafted book: The cover, which shows some bloody manuscripts and a sacrificial dagger, is impressive and the map at the beginning of the book is neat and tidy. At the same time, Óttar’s writing shifts into a somewhat unexpected direction.

Hnífur Abrahams has been described as an historical thriller, similar to The DaVinci Code (2003), and Óttar as the Icelandic Dan Brown. This comparison seems practically inevitable given even a passing glance at the book, and Óttar has mentioned Brown as an influence in the writing of it. Going back to Barnagælur / American Psycho and “Dagur“ / “A Drawing by a Child“, we can see something similar in Hnífur Abrahams. James Donnelly is a famous professor and novelist who gets mixed up in a dangerous adventure when his friend and colleague is killed. He gets in trouble with the police and has to find The Clues and solve The Puzzles in order to get to The Truth, and fall in love with a Clever Woman with Beautiful Eyes. The story moves fast, the chapters are very short and in between car chases the reader is filled in on the truth about Abraham, Isaac and Ishmael; the beginnings of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The basic structure is very similar to that of The DaVinci Code, as are the characters: One could easily imagine Robert Langdon, Sophie Neveu and Bezu Fache in place of James Donnelly, Fatima Parker and John Russel, respectively – with Óttar himself playing the part of Adam Swift, following his characters around Manhattan.

As mentioned earlier, Barnagælur resembles American Psycho in a similar way. But the difference between Barnagælur and Hnífur Abrahams is that the former translates an American fiction onto an Icelandic cultural context, whereas the latter pays no mind to Icelandic culture whatsoever. The story takes place almost entirely on Manhattan Island in New York City and, apart from the half-Icelandic assistant Adam Swift, there is nothing to indicate that this novel is written by an Icelandic author. This probably strengthens the novel’s status as “an international thriller“ and could prove useful in shopping the book abroad, as the strands of Icelandic cultural minutia won’t get stuck in the teeth of foreign readers.

Of course, it can be very interesting to see an author directly engage another author, quoting the other’s works in this way and trying to craft something uniquely his own from the same basic materials. It can, on the other hand, seem weirdly out of turn when the former attempts to poke fun at the latter by parodying motifs or characterization which, at the same time, the former author uses in earnest. And judging from Óttars track record it’s not easy to determine whether that’s indeed the case, or whether Brown’s influence, the story’s setting and the American characters result in the novel sounding like an Icelandic translation of an English original. It’s also curious how much emphasis is put on various characters’ smiles, be they mysterious, devious, secretive, mean, friendly or broad.

Still, the backbone of the novel is its plot and its historical intrigue, and in that respect Hnífur Abrahams does not disappoint. James Donnelly’s adventure revolves around the biblical story of Abraham and his sons, Isaac and Ishmael. According to the Old Testament, Abraham was supposed to sacrifice Isaac but God spared his life and his progeny were destined to be the nation of God, the Jewish people. According to the Quran, on the other hand, Ishmael was the one God demanded in sacrifice, and God spared his life in order for his descendants to form Islam, the nation of God. Donnelly and the others are looking for a manuscript written by Abraham himself, which could shed some light on this discrepancy and perhaps change the world for the better. The idea is that by going all the way to Abraham, the very poster boy of piety and a precursor of both strands of monotheistic religions, we could make some progress towards peace between the warring factions of Christians, Jews and Muslims. The novel also points out the similarities between the sacrifice of one’s son (be it Abraham’s or God’s, in the case of Jesus) and a nation’s sacrifice of its soldiers, thus questioning the idea of warfare in the name of nationalism. While Donnelly is aiming for world peace, high-ranking members of the American government (members of the Project for the New American Century) are trying to find the manuscript and destroy it, as any grounds for peace between Christians and Muslims (not to mention any questioning of a soldier’s duty) would be incompatible with their goals.

And so, in terms of authorial signature, one could say that antipathy for American warmongering and the rewriting of an earlier work of fiction are the only discernable link between Hnífur Abrahams and Óttar’s previous works. And surely his willingness to strike off into unexpected directions and to experiment with other modes of fiction is much to his credit. The anxiety of the person writing about this author, then, stems from grasping at definitions and neat closing arguments with which to break off a lengthy discussion, knowing that most arguments will be null and void by the publication of the writer’s next work. The smart thing to do would be to let the writer define his own self, while avoiding blurby lines about “a young and ambitious author“ or “a scholar of philosophy“, even though both do apply. But in the year 2006 Óttar published the poetry collection AÁBCDÐEÉFGHIÍJKLMNOÓPQRSTUÚVWXYÝZÞÆÖ (2006), where he goes through the whole Icelandic alphabet, writing poems where each word starts with the same letter, from A to Ö. The book starts with three poems in which every word starts with the letter A, then there are two poems with the words starting in the letter Á, and so on. Now upon the Ó-s, the poet puts forth this character description, which is typical of the book:

Óaðgengilega, óbreytanlega, ófrumlega, ófyndna, ógnarsmáa, óhagganlega, óhóflega, óhrausta, ójá – ókarlmannlega, ókáta, ómannblendna – ómenni. Ópersónulegi, órakaði, óraunsæi óreglumaður. Óreiðukenndi óróaseggur, ósamkvæma óskabarn. Óskaplega óskiljanlegur, ósköp ósmekklegur, óstjórnlega óstyrkur. Óttar, óttinn ótæpilegur, óumflýjanlegur, óþarflega óþægilegur.

Any of the poems would be difficult to translate since they trade so heavily on the uniform first letter, and the Ó is of course not found in the English language. In Icelandic the Ó is a negative prefix, as the “in-“ or “un-“ are in English, so an approximate translation would read something like this:

Inaccessible, unchangeable, unoriginal, unfunny, undergrown, unbudging, excessive, unhealthy, ohyes – unmanly, unhappy, unsociable – inhuman. Unpersonable , unshaven, illogical irregularity. Unharmonic upsetter, inconsistent ignoramus. Incredibly incomprehensible, extremely unlikable, uncontrollably unbalanced. Óttar, angst immeasurable, inescapable, unnecessarily uncomfortable.

The alliteration is distracting, the sentences hobble and kick and the coherence is somewhat elusive. As Óttar’s previous works, the book is at times uncomfortable, but never unnecessarily distasteful. The angst is altogether modern, the present inescapably unsettling; the text is even, albeit at times over the top; human disgraces ever-present but unarmingly humorous; Óttar’s antics always enjoyable.

____________________

1. The title is a play on words which can be translated in at least two ways, by combining either the first two words or the two latter words. Ástæða varps translates as A Reason for Nesting while Ást æðavarps translates as The Love Among Nesting Birds, referring to a flock rather than a pair. The title refers to love as a biological mechanism of procreation, both between a nesting pair and a community of serial monogamists.

2. The accompanying drawing of the Prime Minister makes it clear that this is none other than Davíð Oddsson, former leader of the Icelandic right-wing party, the country’s Prime Minister for thirteen years and current director of the board of governors of the Central Bank of Iceland. And a character in two of Óttar’s later books, discussed in turn.

3. The largest church in the country, situated predominately on a hilltop in Reykjavík an often mistaken for the cathedral.

4. The former Prime Minister Davíð Oddsson, mentioned earlier.

5. In traditional use, the word “barnagælur” translates as “lullabies”, but the word “gælur” can also mean “strokes” or “caresses” so in light of the novel’s subject matter the title refers both to singing a baby to sleep and sexually assaulting a child.

6. A controversial bill regarding ownership and by proxy the freedom of Icelandic media. It was the first bill ever to be vetoed by a sitting President, causing an outrage among the ruling majority in parliament.

7. Hannes Hólmsteinn Gissurarson is a right-wing theorist and teacher of political science in the University of Iceland, who has longstanding ties with the Independence Party and has acted as an informal advisor to former Prime Minister Davíð Oddsson.

© Björn Unnar Valsson, 2008