Bio

Pétur Gunnarsson was born in Reykjavík on June 15, 1947. He received his Masters degree (maitrise) in phylosophy from Université d'Aix-Marsaille in France in 1975.

In his career as a writer, Pétur has taken part in numerous cooperative projects. In 1977 he wrote the play Grænjaxlar for The National Theatre of Iceland along with the actors and the music group Spilverk þjóðanna. He wrote the lyrics for the LP Lög unga fólksins, also in 1977 and the play Krókmakarabærinn in the same year in cooperation with the Icelandic Drama School. Pétur has also done work for radio and television, for instance he wrote the script for a documentary on Halldór Laxness in 1988.

Pétur sat on the board of Alliance francaise in Iceland from 1977 – 1981, and was president of the society in 1980 – 1981. He sat on the editorial board of the literary magazine Tímarit Máls og menningar for years and became president of the Writer's Union of Iceland in 2006. Pétur has written a number of articles on literature and culture for magazines and newspapers, and has also published newspaper articles on social matters, as well as speaking on various subjects at different occasions.

His first work, the poetry book Splunkunýr dagur (A Brand New Day) was published in 1973, but before then poems by Pétur had been published in Tímarit Máls og menningar. The novel Punktur punktur komma strik appeared in 1976 to acclaim, the first of four books about the boy Andri. A film based on the book by Þorsteinn Jónsson also became highly popular in Iceland. The last book about Andri, Sagan öll (The Whole Story), was nominated for the Nordic Concil's Literature Prize in 1987. Pétur has sent forward a number of other novels, three of which have been nominated for the Icelandic Literature Prize, as well as his non fiction book about the writer Þórbergur Þórðarson. He has also translated work by foreign authors, among them Flaubert's Madame Bovary and a part of Proust’s A la recherce du temps perdu. Pétur received the DV Cultural Prize in 1996 for the translation of Madame Bovary. In 2023 Pétur received the Icelandic Translators' Prize for his translation of Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Les Confessions).

Author photo: Jóhann Páll Valdimarsson.

From the Author

Why do you write?

Ah, that question! How many times, I wonder, have I answered it, and how interesting it would be to see a list of the answers based on which way the wind was blowing at the time. Yet I have never asked myself this question. It is definitely among those that are not supposed to have a straight answer. It would be anything but fun if someone asked his beloved: why do you love me? And got an answer! A thing or two can be said however. It’s for instance likely that in his formative years the author had a reading experience which awoke in him a longing to recreate the magic himself. I recall the white book palace in Þingholtsstræti (the Reykjavik City Library) and the mysterious note which was glued inside every book cover: “In case of an infectious disease in a customer’s home, please inform the library immediately.” Hereby I inform about an infectious addiction to reading: Enid Blyton and the Famous Five books, Örn Klói with his Icelandic Tarzan, The Blue books, The Odyssey. I remember a pile of books by the headboard of my bed, many of them way past their due date and already collecting outrageous fines. And let us not forget the bookstores of the fifties and the sixties. Back then, books had not been placed inside the unbreakable armour that is customary now (to prevent infection?) and if you bought a book you had access to all the other books in the store, granted that you were careful not to break its spine. Soon you were able to read a book as if you were looking down a ravine. After reading it you would rush downtown with the book and exchange it for another, in one of the innumerable downtown bookstores. At the time there were four things which were thought to be uncountable in Iceland: the islands in Breiðafjörður, the hills in Vatnsdalur, the lakes on Arnarvatnsheiði and the downtown bookstores.

***

At present, reality comes to us in an overflow of net- and visual media, up to the point where influential theorists proclaim that it no longer exists or rather, that it is merely an idea like any other idea. During such a violent storm it is the author’s responsibility to put weights on the valuables that he doesn’t want to get blown into the wind. Resistance to oblivion. Our software is threatened by a virus that no one knows where has come from, and it is programmed to wipe out the contents of as many files as possible. The author’s endeavour becomes a sort of an anti-virus program, aimed at damage control, to prevent the losses of wealth and context.

***

At the beginning of his career, the author believes that success depends on thinking of a brilliant idea. He is like a gold digger, sifting through the river’s flow for days hoping for a grain of gold. As time goes by, he begins to feel as if he has gone deep below the surface of the earth and has to play his cards right so that his lifetime will last him to carry a fraction of the riches that he thinks he senses into the daylight.

Pétur Gunnarsson, 2002.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

About the Author

On The Works of Pétur Gunnarsson

To capture the everyday in writing is an intricate project. On the one hand it can involve describing the minutiae of everyday life; the things that escape our attention in our daily routines, but nevertheless weave part of the web our life forms; i.e. the process of writing the ordinary. On the other hand it can involve attempts to locate the poetic in daily life, by turning our attention to the miracles hidden in the everyday and giving them meaning. Pétur Gunnarsson has in his works devoted himself to this project and all that it entails. Perhaps one can suggest that his choice of works in his outstanding translations is also formed by this interest: Flaubert (Madame Bovary) with its ordinary (as opposed to unremarkable) characters – and Proust who attempts to preserve every memory, every scrap of his life in his search for times past. This process is not only evidence of a literary interest in the everyday, or means that the author has simply found a useful and fertile subject matter, rather it seems that this bears witness to a desire to prevent life from disappearing and being forgotten, and this need the author attempts to satisfy in writing. This is evident in many respects in Pétur Gunnarsson’s works, in his novels and “pocket books”, but with his pocket books he has formed the works specifically with this goal in mind – and the reader gets an insight into the raw material of fiction.

In Persónur og leikendur [Cast of Characters], Andri, the protagonist of a four volume ’coming-of-age’ work, announces his intention to write a novel and Bylgja, his girlfriend, asks what it will be about: “Only fiction can prevent us from being constantly divided into lesser people, Andri started. The need has never been as pressing to connect the small particles reality has divided into and while reading the book the reader discovers these connections. We have to bring to fiction what we lose in the business of real life.” (Persónur og leikendur, p. 103).

One of the preoccupations of writers in the last thirty years or so, is the relationship between reality and fiction. At times this has manifested itself in increased interest in autobiographical writing, which focuses on the role of fiction in representing the real, and at times it manifests itself in works which focus on the possibilities and limits of fiction’s connection to reality. In Pétur Gunnarsson’s works this is evident in fictional biographies, be it Andri’s youth in Punktur punktur komma strik (1976), Ég um mig frá mér til mín [1978; Me, Myself and I], Persónum og leikendum (1982) and Andri’s and Guðmundur Andri’s lives in Sagan öll [1985; The Whole Story]; the life of a family in Hversdagshöllin [1990; The Palace of the Everyday] and Efstu dagar (1994) and finally the biography of Iceland he began with Myndin af heiminum [2000; The Picture of the World] – the exception then is the crime novel Heimkoma [1997; Homecoming], which still touches upon some of the author’s preoccupations.

Pétur Gunnarsson’s first novels already bear witness to many of his main preoccupations and stylistic traits. The books on Andri are first and foremost urban literature. The city always takes centre stage, eventhough the characters take trips out of town and summers are spent in the country the viewpoint is always urban. Urban life is taken for granted, it needs no explanation or definition – this is where the everyday happens. The interest in the city as a setting for fiction is also very apparent in Pétur Gunnarsson’s essays on literature, for instance in the collection of essays Sykur og brauð [1987; Sugar and Bread] where he praises a book by Hafliði Vilhelmsson specifically for its subject matter: “Everyday city life” (Sykur og brauð, p. 38). But if there is any kind of comparison made, it is not the traditional and ubiquitous city vs country, but much rather Iceland vs other countries. This is much in evidence in the description of Andri’s travels and homecoming. And it is in this friction that occurs when people return to their homeland after many years spent living abroad that the comparison gets its dramatic tension as it does in Heimkoma. This is not a description of a journey from country to city, or only if one considers Iceland to be the country and abroad one endless metropolis, this is the Icelander who has become a foreigner and needs to come to terms with the nation.

Another strand in Pétur Gunnarsson’s work is also apparent in his first novels; his firm grip on, play, curiostiy and interest in language – all this creates a rich, light style, which constantly surprises the reader. He is a master of word play and in turning the language on its head, sometimes literally as Svanur does in Persónur og leikendur. Pétur Gunnarsson’s text often finds surprising connections, often by using personification and similes. The relationship and similiarities between people and animals makes the reader see both in a new light and this is apparent already in his first novel: “The cat walked up, stopped and smelled this plastic animal, dipped its paw a couple of times in the puddle to check if the water was wet: a billion years of evolution had not sufficed to teach it once and for all, neither had it given it enough time to buy some wellingtons” (Punktur punktur komma strik, pp. 20-21). The vocabulary of his works is a successful mixture of colloquial language and literary vocabulary and it is clearly contemporary wihtout following every trend in slang.

The books on Andri mentioned above, describe a highly enjoyable ’coming-of-age’ story, and they quickly became very popular and a film was made based on the first novels. The subtitle could well be, ‘How one becomes a person’, as they focus a great deal on the creation of an identity. They investigate what happens to the material that is so vague to start with, it hardly seems to exist and seems to turn into a chameleon during the teenage years, as the title Ég um mig frá mér til mín [Me, Myself and I] indicates it describes the teenager’s endless search for a self, but it is all very vague as “the character is rubbed out at night” (Persónur og leikendur, p. 22), and in Sagan öll the protagonist suffers from this literally because of amnesia and his forgetfulness means that he constantly has to create himself (Sagan öll, p. 269). These thoughts on the search for self and identity are also reflected in ruminations on the difference between fiction and reality. In Hversdagshöllin the narrator discusses what watching films does to our experience of our own lives: “In the cinema life is finally how one believes it to be […] this life that we try unsuccessfully to create in gardens and alleys and backyards – here it blooms.” (Hversdagshöllin, pp. 103-4). But films are in some ways lacking: “In the cinema life is much more concentrated than the everyday. But still in some ways narrower, for instance, one never sees anyone on the toilet, a whole meal is seldom eaten and people never sleep in.” (Hversdagshöllin, p. 104).

In Hversdagshöllin it says that only trains and novels move on a straight line, reality always takes the side roads (Hversdagshöllin, p. 152), and Pétur Gunnarsson investigates these side roads. The uneventful everyday attracts and Pétur Gunnarsson describes in his collection of essays Aldarför (1999) that his favourite months are January, February, March, as they are the true everyday months, (Aldarför, p. 7). It is not at all a simple project to capture the everyday in writing. There are many different solutions and possibilities and Pétur Gunnarsson’s interest is manifold; he freezes the moment, attempts to “capture” reality, and writes about everyday reality, but also the strange and unique and the remarkable in the details and last but not least he investigates where the borderline between reality and fiction lies. This manifold interest is apparent in the title of Hversdagshöllin, but this word also appears in Sagan öll where the family home is called the palace of the everyday (21). In many ways one could claim that Sagan öll is at the centre of Pétur Gunnarsson’s works up until now, as in it one can find the kernel of most of his subject matters, forms and stylistic traits manifested to some extent in all his works.

When referring to family sagas one usually means works that trace the story of a few generations in the spirit of Galsworthy and Mann, but in Sagan öll Pétur Gunnarsson concentrates mostly on its smallest component, a couple with one child, that is at once the contemporary family and the part that all the other parts of the family are based on. Discussion of the everyday is much in evidence, as here we have a protagonist suffering from amnesia and he therefore has to write everything down to preserve it, and he also works at home, where the everyday truly lives and where small things are taken care of. What motivates the call to freeze the moment is a fear of forgetting. This fear of forgetting has not only a private reference in contemporary fiction, but also political reference after World War II, this is perhaps the reason that the amnesiac Guðmundur Andri is one of the most striking characters in Pétur Gunnarsson’s works. The narrator points out that what is written down happens again and again (Sagan öll, p. 266), and the author therefore battles forgetfulness on behalf of us all. In Sagan öll Pétur Gunnarsson concentrates on the ordinary, on the everyday that is full of miracles, (Sagan öll, p. 41). This need to capture the moment and prevent it from disappearing also brings anxiety and fear. In Sagan öll it says:

Isn’t it enough just to live? Does one have to live for a purpose? Live to type?

I am cleaning the living room, it’s snowing, Hringur cycles in circles on the living room floor, busy with the art of cycling. Round and round.

If this could last forever, I think and stroke happiness, already missing the moment that will pass.

Is it from the cinema this idea that we transpose on life: a chain of events running through with oneself at the centre?

But it doesn’t work out and the difference between the real and the idea causes misery. We have to create ourselves EVERY DAY! The script constantly changes [. . .]

Eventhough it ends, eventhough I will lose it, I am here now and with a broom and dustpan and Cheek to cheek playing – happy.

And not another word! (Sagan öll, pp. 268-9).

Pétur Gunnarsson also points out that fiction is sometimes superfluous as in the travel description in Sykur og brauð (p. 65), where reality is all we need in all its strangeness. In his “pocket books” (Vasabók 1989 and Dýrðin á ásýnd hlutanna 1991) there is an ode to the moment, where he intends to capture life in writing (Vasabók, p. 14), he will not change it and leaves fiction behind and all that is made up, he wants to mediate the everyday as it is. The pocket books are in some aspects similar to diaries, in the sense that they do not interpret events with the benefit of hindsight, rather they chronicle what the everyday offers. They are a collection of short chapters, but sometimes we get narrative continuity as in a description of a trip abroad (Vasabók, pp. 20-22). At first sight they seem formless, but upon closer inspection motifs appear and refrains, such as the boys playing chess in Vasabók. In Dýrðin á ásýnd hlutanna Pétur Gunnarsson says the everyday is overflowing with events (p. 9) and describes how he wants to turn everything into fiction (p. 17). The role of the pocket books is to preserve the moment, “so life won’t disappear without a trace” (Dýrðin á ásýnd hlutanna, p. 11), that is why one needs to take them everywhere, it is not enough to sit down and write when you get home, because there is always something that gets lost on the way. Here we are certainly on the borders of fiction and these works describe a strong need to link text directly to reality.

There is one part of life that is in the foreground in Pétur Gunnarsson’s works and that is childhood. It is described from the viewpoint of a child, who has of course the ability to sense the miracles in the everyday. This is counterbalanced when childhood is viewed through the eyes of a father, who watches his child and tries to interpret its insight and its games, and tries to see the world as a child in order to find fiction, and he says in Dýrðin á ásýnd hlutanna “if one could write like children play” (Dýrðin á ásýnd hlutanna, p. 40). At times the works are concerned with a lost childhood, and sometimes with childhood that is all around us but we seldom notice. Childhood is not romanticised in a traditional manner, and its dangers and insecurities are not glossed over. The child’s viewpoint prevents us from taking life for granted. The closing words in Sagan öll are directed to a child: “you filled this cold void with life” (Sagan öll, p. 273).

Works where family life and the everyday are in the foreground do not get their dramatic tension from remarkable or strange events. There is enough drama in the everyday however, and one can point specifically to divorce that is almost a motif in Pétur Gunnarsson’s works (see for instance Myndin af heiminum, p. 60). The works are also concerned with fathers that are usually on the edge of the life of the everyday and the family: “Dad is like a broken imperative” (Sagan öll, p. 147), it says in Sagan öll, but the work also provides a picture of a different kind of fatherhood, where the father is the centre of the family.

Pétur Gunnarsson’s connection with Icelandic literary tradition merits a closer inspection. Halldór Laxness is so imposing on the Icelandic literary scene that in Pétur Gunnarsson’s works he appears literally as a character. He is already there in the first novel (Punktur, p. 24) and in Persónur og leikendur which is concerned with how one becomes a writer, he is a constant presence: “am in the period Halldór Guðjónsson from Laxnes 1921” (Persónur og leikendur, p. 10). In this work it is part of being an Icelandic writer to go through a “Laxness” period. Pétur Gunnarsson has published two collections of essays Sykur og brauð and Aldarför. They provide a good insight into his literary thought, where he talks of both his own works and works of others. In Aldarför he writes on Þórbergur Þórðarson and says for instance: “The collection on Suðursveit is a lesson in how everyday life can have an eternal life in a story” (Aldarför, p. 105). He compares Þórbergur Þórðarson and Proust and says that they both describe a paradise lost, and not least: “both pretend to trace a strictly factual biography and lull the reader into conditionless following, but make things up without hesitating when they see fit” (Aldarför, p. 127). Perhaps, all things considered, Pétur Gunnarsson is not the heir apparent of Halldór Laxness but much more of Þórbergur Þórðarson – examples are for instance descriptions of the everday, as when Þórbergur Þórðarson describes his daily and uneventful meanderings in the chapter “Rigningsumarið mikla” in Ofvitinn and when he weaves fiction into the everyday when he meets his love in Íslenskur aðall. He breaks new ground not least in his writing on childhood in Sálmurinn um blómið, where the everyday is filled with miracles.

© Gunnþórunn Guðmundsdóttir, 2002.

Articles

General discussion

Torfi H. Tulinius: “Pétur Gunnarsson (1947- )” Icelandic Writers.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 293, ritstj. Patrick J. Stevens, Detroit, Gale 2004, s. 283-294

Torfi H. Tulinius: “Snorri og hans slægt i moderne nordisk litteratur”

Ordenes slotte (edited by Auður Hauksdóttir, Jørn Lund and Erik Skyum-Nielsen), pp. 31-38

See also: Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 436, 443, 455, 460, 468, 495, 602

Awards

2023 - the Icelandic Translators' Prize for translation of Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Les Confessions)

2011 – The Knight’s Cross of the Icelandic Order of the Falcon: For his writing and contribution to Icelandic literature

2009 – The Hagþenkir Non-Fiction Award: ÞÞ – Í fátæktarlandi and ÞÞ – í forheimskunarlandi (Biography of writer Þórbergur Þórðarson)

1999 – The Þórbergur Þórðarson Award for Excellence in Style

1998 – The National Broadcasting System´s Writer´s Award

1996 – The DV Cultural Award: for his translation of Madame Bovary (Frú Bovary) by Gustave Flaubert

Nominations

2007 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (non-fiction): ÞÞ í fátæktarlandi: Þroskasaga Þórbergs Þórðarsonar

2000 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (fiction): Myndin af heiminum

1990 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (fiction): Hversdagshöllin

1987 – The Nordic Council´s Literary Award: Sagan öll

Pont pont vesszöcske

Read more

HKL ástarsaga (HKL a love story)

Read more

Skriftir (Writings)

Read more

Veraldarsaga mín - My world history

Read more

Veraldarsaga (mín)

Read more

Die Rollen und ihre Darsteller

Read more

Íslendingablokk (Icelanders´ Block)

Read more

Punkt punkt komma strich

Read more

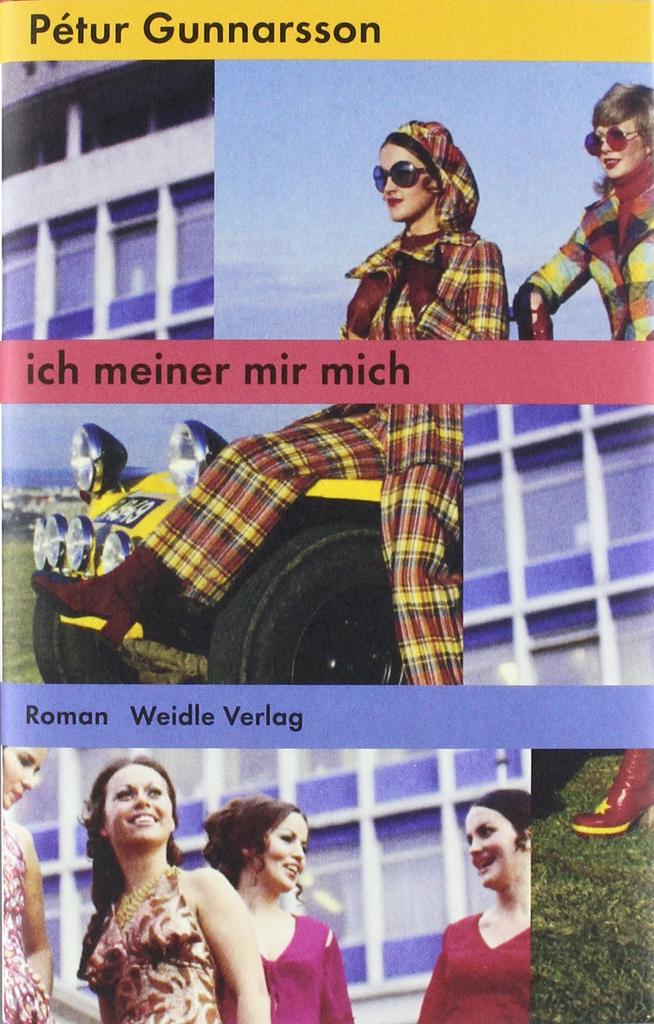

Ich meiner mir mich

Read more