Bio

Brynhildur Þórarinsdóttir was born in Reykjavík on August 27, 1970. She studied Icelandic language and literature at the University of Iceland, graduating with an M.A. degree in 2004. A year later she received a teaching diploma from Akureyri University. Between studies, Brynhildur worked as a journalist and column writer, for newspapers, magazines and radio. She was the editor of literary magazine Tímarit Máls og menningar for a while. She has worked as a teacher along with her work as a writer, at Akureyri University among other schools.

Brynhildur's first published work of fiction is the short story Áfram Óli (Go for it, Óli) that received first prize in a competition hosted by the Association of Native Language Teachers in 1997. Three of her books since then are retellings of Icelandic Sagas for children, The Saga of Njáll, The Saga of Egill and Laxdæla. The first has also been published in translations. Brynhildur received the Icelandic Children's Book Prize for her book, Leyndardómur ljónsins (The Lion's Secret) in 2004. She won the Nordic Children's Literature Prize in 2007 for her retellings of three Icelandic Sagas, Njála, Egla and Laxdæla.

From the Author

From Brynhildur Þórarinsdóttir

No literary genre comes closer to nostalgia than children’s literature. We grown ups compare the books of our children to the ones we read as youngsters and have a hard time understanding why they are not as amusing and charming as ours were. The sweet smell of youth surrounds us when we think about our favorite books from childhood, we sense the smell of sun-dried linens, the heat from a flash light that has been used for too long, and the striped taste of Signal2 on our teeth. We put the heroes of today up on the old bookshelf in our childhood room, between Árni from Hraunkot and little Hjalti, measure whether they are as full of life as Pippi or as brave as Ronja, as forceful as Georg(ina) and as well behaved as Pippi’s friend Anna.

I read them all, and now it gives so much pleasure to remember them: the blue books, the red ones, Astrid Lindgren, Enid Blyton, Spirou and Fantasio (French comic books), and Jón Oddur and Jón Bjarni by Guðrún Helgadóttir. My mother introduced me to Dóra and Vala by Ragnheiður Jónsdóttir and my dad to Tom Swift. I went upstairs to granny and swallowed down her folk stories, always hungry as the girl Gípa from the folk stories, got acquinted with ghosts and goblins and found fairies in the garden. I got to know Alice in Wonderland through a series in an Icelandic newspaper and Ivanhoe in the magazine Sígildar sögur (classic stories). At the same time I took Danish lessons on Paradiseæblevej, because the Danish publication of Donald Duck (Kalle Anka) was delivered to our house since long before I was born. My grandmother’s attic contained treasures, there you could find my dad’s old Tarzan books, worn and with small print, but utterly exciting. I carried them down the steep steps and then got lost in the jungle. Shortly thereafter I followed Tintin to Congo and my Africa lessons were completed.

One of my favorite books was called Litla Inga og stóra Inga (Little Inga and Big Inga, [the original is Store Ingrid og lille Ingrid, ed.]), and it had also been my mom’s favorite. It told the story of an orphaned girl that was lucky enough to meet an old woman, which took her in. Litla Inga og stóra Inga was a beautiful book and little Inga’s luck brought tears to my eyes every time I read it. I read the book about little Inga and big Inga again a few years ago, but should not have done that. It didn’t tell the story of an old woman who saved a little orphan. Little Inga was a grown kid, and even worse, big Inga wasn’t an old woman at all – she was my age. She was thirty! “Poor big Inga”, it says in the book, “how fortunate she was to receive this child in her loneliness, having reached thirty and still without a husband and child.” I finished the book without shedding one tear, and then stuck it as far up on a shelf as I could. There it will stay until I loose myself in nostalgia and give it to my daughter to read.

It must be the dream of every children’s book writer to write books that children will cherish as sweet memories when they grow up, books that withstand time and still move you when you take them down from the shelf 20 or 30 or 70 years later. These books are of course not “only” children’s books, they are family books, books that grandmothers and grandfathers, mothers and fathers, big brothers and sisters enjoy reading with their kids. In my opinion, there should be a family bookshelf in every home, where all family members put their favorite books. The shelf should of course be within easy reach of small and tall alike, so the children can read their parents chosen books and the parents their children’s favorites. In that way, we not only bridge the gap between generations in the home, but also in cultural history, we introduce Harry Potter to the Icelandic sorcerer Sæmundur, Gunnar from Hlíðarendi meets Leda the swordbearer, and Emil gets to know the Icelandic prankster Mói. I am in no doubt that the shelf-people will have great fun, just as the family members.

Brynhildur Þórarinsdóttir, 2006.

Translated by Kristín Viðarsdóttir.

About the Author

Brynhildur Þórarinsdóttir - Of Heroes, Lice and Clever Kids

Brynhildur Þórarinsdóttir is a relative newcomer in the field of children’s literature. Her first work is a short story, "Áfram Óli" (Go for it, Óli) which appeared in an anthology of short stories published by the Association of Native Language Teachers and Mál og Menning publishing house in 1998, as well as in Skíma (the journal of Native Language Teachers) in that same year. The story is about three friends, Óli, Tarsan and Magga (the narrator), telling a story that happened a long time ago. It is a nostalgic tale, with the now adult Magga recounting events that happened one summer during her school years. The story is not a long one, yet it deals sensitively and intuitively with serious matters, such as the death of loved ones, and grief, and also remembrance of lost youth, a time of play and innocence. One of the three friends has a serious accident during the summer of the story, and this changes the lives of the other two a great deal. When Óli dies, he leaves a great and irreparable chasm in this little circle of friends and nothing is ever the same again. Since the publication of "Áfram Óli", Brynhildur has written two novels for children and young people, and two books which are adaptations of Icelandic Sagas. Brynhildur has also written numerous articles about the Icelandic Sagas, Icelandic culture and much else.

The first of the two Icelandic sagas edited and adapted by Brynhildur was Njál’s Saga, which in her version is entitled simply Njála (2002). Last year saw the publication of her second adaptation, of Egill Skallagrímsson’s Saga, bearing the shortened title Egla (2004). Both books are vividly and carefully put together and the sagas come across well despite the unavoidably high degree of shortening involved. Primarily aimed at children of school age, the sagas are also a good introduction for other readers to the plots and personalities of the Sagas in a simple and approachable format. In order to maintain a connection with the original Saga texts, many of the more celebrated passages and verses are preserved unshortened, with marginal annotations where the language needs explication. Good use is made throughout of marginal notes to clarify concepts unfamiliar in modern speech or writing: the expression “dung-beardling” for example, which appears frequently in Njála and is undoubtedly strange to the modern reader. Events both within and external to the narrative also receive explanation where needed to throw further light on the stories. Each book begins with an exhaustive foreword covering events which are important to the plot of the Saga but which have been edited out of the main text, and also illuminating the circumstances of Icelandic life during the Saga age, such as trade, shipbuilding and domestic arrangements. The vividly entertaining drawings which grace every page are by Margrét Einarsdóttir Laxness, illustrator of many children’s books.

Brynhildur’s first full-length novel is Lúsastríðið (The Louse War), published in 2002; it tells the story of three lively and mischievous children who are ready to pull any trick to wangle a much longed-for break from school. One of them finds a cap infested with headlice and they decide all to wear the cap so as to catch lice themselves, and then they get all their classmates to join in. Eventually the whole school is infested, and parents and staff are completely at a loss as to why they are unable to get rid of the lice, despite their repeated attempts to do so. The children are scrubbed, washed and combed daily, but to no avail, as the children have taken care to keep the lice alive in the cap, which they all put on every day in order to keep the infestation going. In the end the only solution seems to be to close the school for a week. Of the three friends it is Inga Þóra who is the narrator, with the two boys Maggi and Benni also playing major roles in the story. During the break from school the three spend a lot of time together and get up to all manner of pranks which create a great deal of anxiety for their respective parents. They play, for example, at ten-pin bowling in Inga Þóra’s apartment, using soft-drink bottles filled with water for the pins, and her father’s bowling ball, causing irreparable scratching of the parquet floor and considerable water damage to the building. Later Inga Þóra and Maggi try ski-ing down the staircase of Inga Þóra’s apartment block, which ends in catastrophe when Maggi is badly injured, and the two sets of parents clash when they find their children lying hurt on the landing. Despite the three children’s success in keeping the lice alive, and in the struggle for permission to enjoy themselves during the break, eventually after a week it all comes to an end and they have to return to school. At first their classmates are not particularly pleased with them for having more or less forced them to suffer headlice for a whole week, but in the end they their honour is restored with a remarkable offer from an unexpected source.

Lúsastríðið is a very funny book, and the unbelievable escapades of Inga Þóra and her friends entertain the reader although they occasionally go a bit far. Often disaster is just round the corner, with the episode of the staircase ski-ing accident an obvious example. Despite the great humour and joie de vivre of the children, one can detect a more serious undertone in the book concerning the parents of Inga Þóra and her friends, along with various other grown-ups who play a part in the story. The reactions of their parents to their escapades during the closure of the school are understandably very harsh, given that Inga Þóra and her friends have succeeded not only in ruining her flat, but also in damaging half the apartment block.

Inga Þóra’s view of her parents’ reaction is that they are more concerned about their parquet floor and other worldly possessions than about her, and there is plenty of evidence to back up this view. Inga Þóra herself wants nothing better than to be a good daughter, but unfortunately things go awry for her, and her parents misunderstand almost all she tries to do for them. The atmosphere in the home goes from bad to worse every day the children are away from school, and their parents have little time to be with them because all their time goes in working to afford the things they feel the need to acquire, so the children take a back seat. The nadir is reached when Maggi’s parents leave him unattended in the shower, helpless with his broken leg, and it is only by chance that Inga Þóra finds him and is able to rescue him. In the end, however, the children succeed, with the help of Inga Þóra’s grandmother and Maggi’s grandfather, in bringing their parents back in line and teaching them that it is not worldly possessions that matter most in life.

Throughout the book Inga Þóra ponders the questions of life and her future, and her thoughts bear witness to a rich imagination, as do the escapades which lay waste to her parents’ apartment. When Inga Þóra, Maggi and Inga Þóra’s grandmother (who is supposed to be making sure she doesn’t come to any harm while away from school) play hide-and-seek, grandma gets locked in a cupboard, and though Inga Þóra is at first not bothered, she is suddenly struck by these thoughts:

“What if grandma were really dead inside the cupboard? Nobody would believe that she’d shut herself in there playing hide-and-seek. We’d be dragged out handcuffed and with lead weights shackled to our legs. Then we’d be charged with murder and sent to a high security prison island in the middle of the North Atlantic with bloodhounds prowling the cliffs. Maggi would waste away in his cell and die of consumption and I’d try to escape and would be eaten by a shark when in sight of land. Such would be my fate.”

(Lúsastríðið p. 54)

Again, when Inga Þóra’s parents get the bill for the damage she and her friends have caused while school was closed, her imagination runs riot:

“Mamma obviously wanted to keep me as far away as possible from home. Maybe she wanted me never to come back. The more I thought about it, the more sure I became. I would have to run away. I could see it all. I would pack the essentials in a big handkerchief, knot it fast and hang it on a stick. Then I’d take my share of the coins from the box under Maggi’s bed. Pity there are no trains in Iceland, otherwise I’d hide in a freight wagon and live off bruised apples.”

(Lúsastríðið p. 114)

These words demonstrate clearly that the book is not simply an amusing and entertaining children’s storybook, but also conceals a message to those parents who seem often to forget their children and their needs – even what it is, and was, like to be a child.

Brynhildur’s latest book is Leyndardómur ljónsins (The Secret of the Lion) published in 2004, for which she won the Icelandic Children’s Book Award. It tells the story of the twins Tommi and Anna, who go with their classmates to summer camp at the school at Reykir in Hrutafjord. The children look forward to fun days at camp; at Reykir they join with a party of Year Sevens from Akureyri, amongst whom Tommi and Anna quickly make friends. Soon after their arrival, however, strange events start happening: the electricity unexpectedly fails throughout the school, they see a menacing figure creeping about in the dark, indoors and out, and the boys hear someone reciting names in an adjoining room. But things start getting seriously complicated when Tommi, Anna and two new-found friends get shut in the gymnastics equipment cupboard and make the surprising discovery of an old picture with a mysterious inscription, hidden in one of the mats. The picture leads them on a trail of remarkable events which occurred at Reykir during the Second World War, and it transpires that the man who creeps about the house at night is trying to find out about events connected with the picture. An old couple who live at Reykir and look after the school buildings seem also to know more than they admit, and soon secrets start resurfacing.

Leyndardómur ljónsins is and original and entertaining book for youngsters, building as it does on elements which have long been popular in such books. Summer camp, hidden riddles, secrets, and children playing the part of spies are all well-known features of literature for the young, not forgetting bittersweet teenage love. Brynhildur succeeds in knitting together these familiar elements and giving them a new point of view by mixing in unfamiliar events and characters. The most remarkable part of the story is the ‘Lion’s Secret’ secret itself; without giving it away here, it is safe to reveal that it is connected with the inscription on the picture, and the affair is bigger and more complex than anyone suspects. The mysteries solved by children in Icelandic young people’s books tend, at least in most cases, to be small ones, connected with minor crimes and criminals, but in this newest novel it is safe to say that Brynhildur travels paths hitherto untrodden.

Tommi and Anna are complete personalities who balance each other; Tommi is shy and reserved whereas Anna is open and lively. The author lays great stress on the twins’ strong and close relationship, and the concern they show each other gives the book a friendly and positive style, despite the tragic events that occur at the school camp. Both Tommi and Anna, and their friends from the North, Valdís and Harri, are sympathetic and authentic characters, who experience both positive and negative thoughts, but most of the time do not allow their emotions to run away with them.

Brynhildur Þórarinsdóttir clearly has a great deal to offer as a writer of books for children and young people, and her stories create a new benchmark for a long-established tradition in the genre. The reader is quickly captivated by her light and humorous style, but beneath the lightness there runs always a serious, though never overpowering, undercurrent. Brynhildur’s retelling of the Icelandic Sagas are a much-needed addition to the children’s literature that flourishes today, vital as it is that young readers should become acquainted with this important literary heritage of the Icelandic nation, which for many of them is familiar only as a compulsory exercise in secondary school. Though crammed full of knowledge, they are in no way overwhelming, and will encourage an interest both in the Sagas themselves and also in this important period of Iceland’s history.

© María Bjarkadóttir 2006.

Translated by Björg Árnadóttir.

Awards

2007 - The Nordic Children´s Literature Prize: Njála, Egla and Laxdæla (retellings of Icelandic Sagas)

2006 - Town Artist in Akureyri

2004 - The Icelandic Children´s Literature Prize: Leyndardómur ljónsins (The Secret of the Lion)

2003 - IBBY Iceland Award: Njála (retelling of Njál´s Saga)

1997 - First Prize in a short story competition hosted by The Icelandic Association of Native Language Teachers: "Áfram Óli" (Go for it, Óli)

Nominations

2018 – Fjöruverðlaunin, the Icelandic Women's Literature Prize: Gulbrandur Snati og nammisjúku njósnararnir (Stripe and the Candy-Crazed Covert Agents)

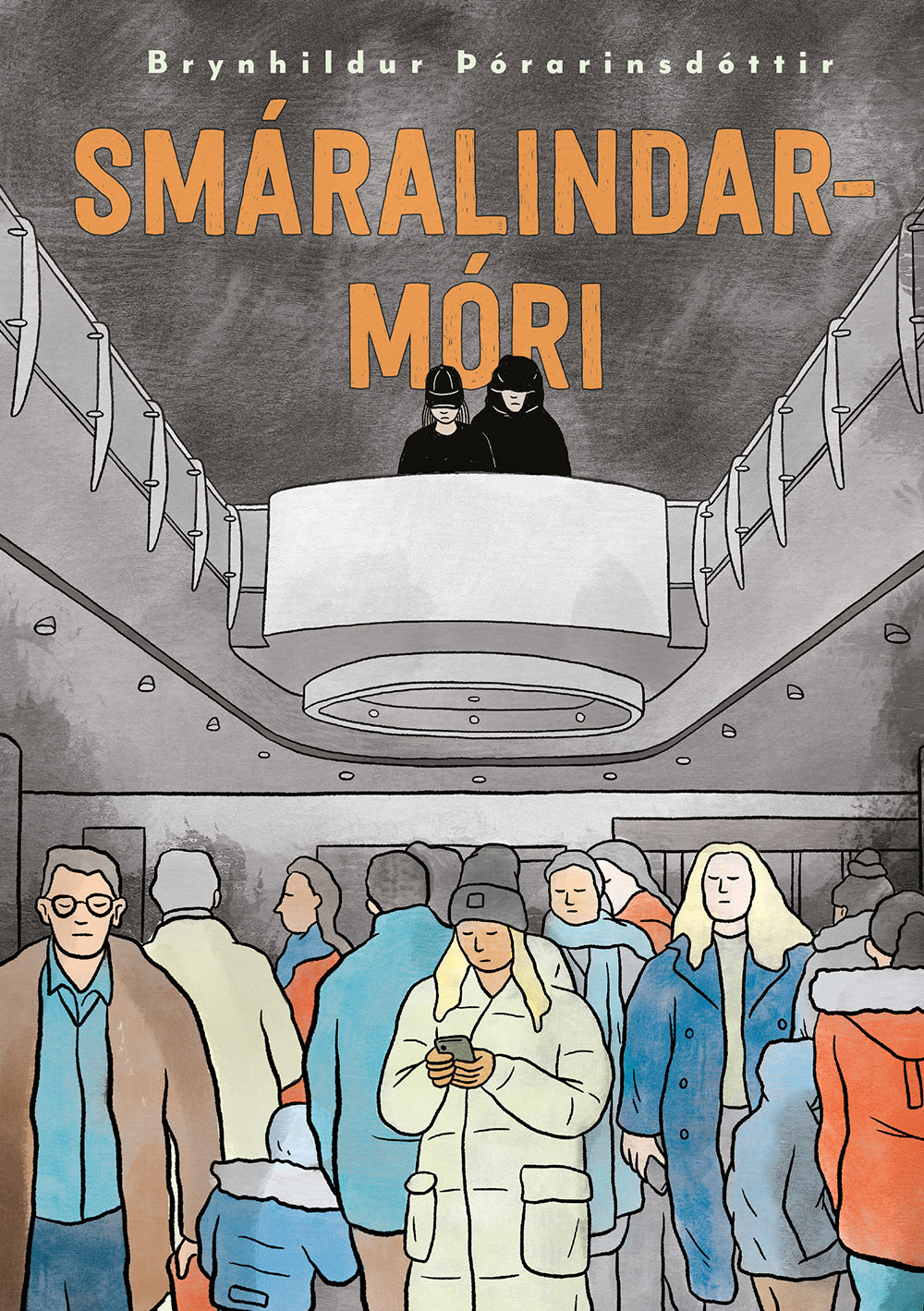

Smáralindar-Móri (The Haunted Mall)

Read moreHún hættir, finnst eins og einhver sé að fylgjast með sér. Hún snýr sér laumulega við og gjóar augunum um rýmið. Henni finnst þetta óþægileg tilfinning en innst inni vonar hún samt að það sé rétt; að hann standi þarna dularfullur og dreyminn og horfi á hana.

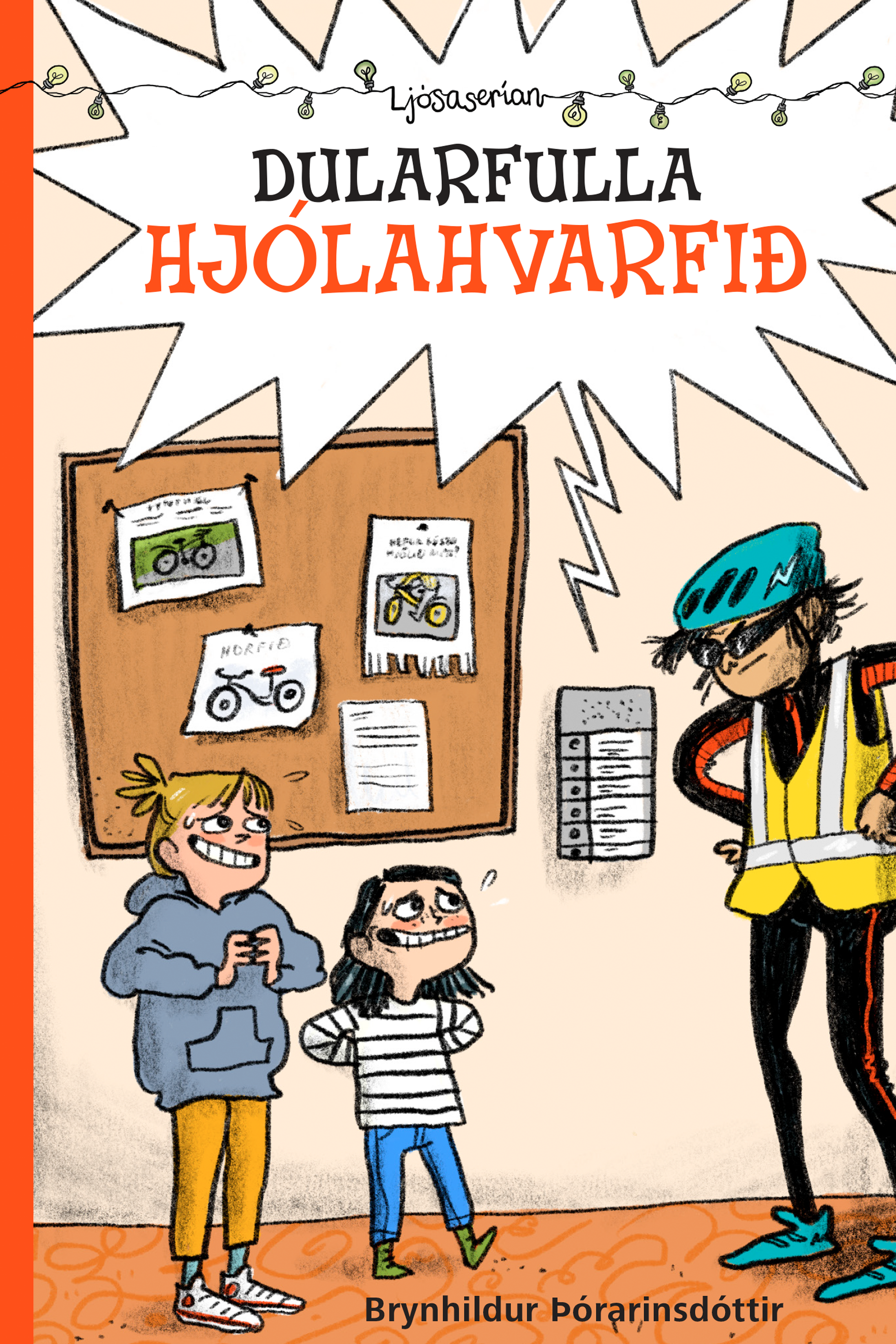

Dularfulla hjólahvarfið (The Mystery of the Missing Bicycles)

Read more"Hvernig töluðu krakkar saman í gamla daga, sko þegar þú varst lítill og það voru engir símar til?"

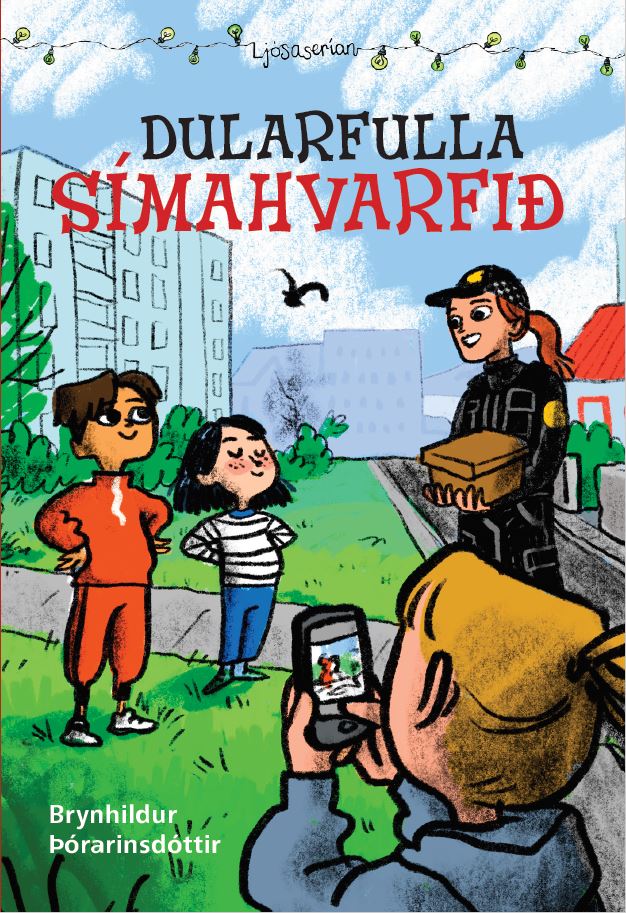

Dularfulla símahvarfið (The mysterious phone disapearance)

Read more

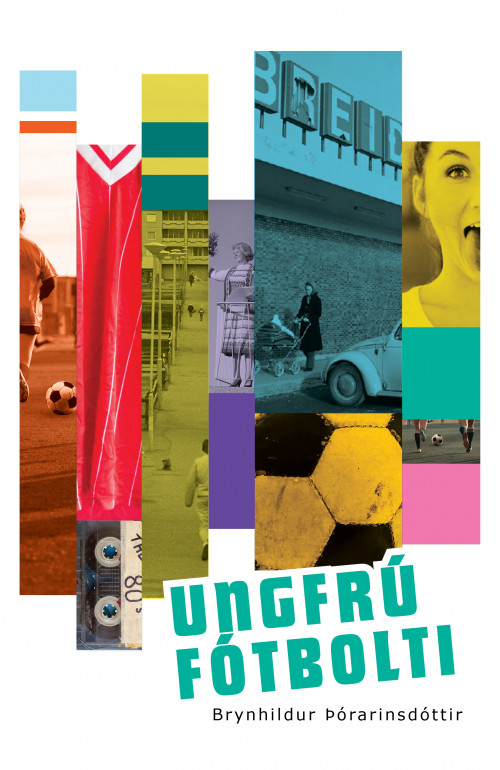

Ungfrú fótbolti (Miss Football)

Read more

Gulbrandur Snati og nammisjúku njósnararnir (Stripe and the Candy-Crazed Covert Agents)

Read more

Blávatnsormurinn (The Wyrm of Blue Lake)

Read more

Óskabarn : bókin um Jón Sigurðsson

Read more

Gásagátan: spennusaga frá 13. öld

Read more

Síðasta skíðaferðin (The Last Ski Trip)

Read more