Bio

Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir is a native of Reykjavík, born August 25th 1954. She studied history at the University of Lund in Sweden from 1973-74, and history and art at Instituto Allende in San Miguel de Allende Guanajuato, Mexico from 1977-78. She completed her Cand. mag. degree in history from the University of Iceland in 1993 and has worked as a writer ever since. Þórunn has written a large number of books – novels, books of poetry, biographies and scholarly works – as well as a number of articles and programs for radio and television. She has co-authored two books with songwriter Megas: the childhood memoir Sól í Norðurmýri (Sunshine in Norðurmýri, 1993) and the novella Dagur kvennanna (2010).

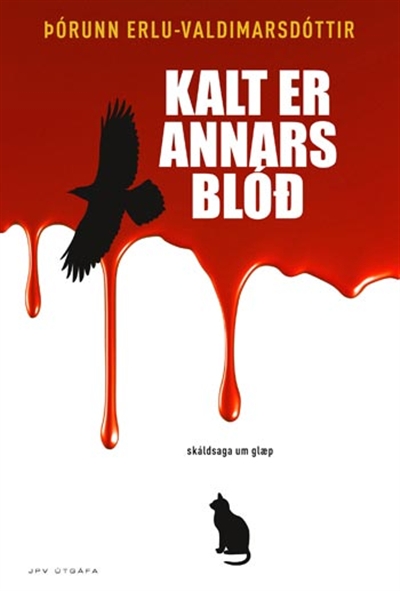

Þórunn´s first novel, Höfuðskepnur (Elements) was published in 1994. The novel Alveg nóg (Enough) was nominated for the DV Cultural Prize in 1997; Stúlka með fingur (Girl With a Finger) received that same award in 1999 and was also nominated to the Nordic Council´s Literature Prize in 2001. Þórunn´s novels Kalt er annars blóð (Cold is the Blood of Another, 2007) and Mörg eru ljónsins eyru (The Lion Has Many Ears, 2010) are contemporary crime stories, based upon the sagas Njála and Laxdæla, respectively. These were both nominated for the Icelandic Literature Prize in the category of fiction, but Þórunn has thrice been nominated for the Prize in the nonfiction category, namely for Snorri á Húsafelli (Snorri from Húsafell, 1989), Til móts við nútímann (Towards the Present, 2000; as one of five authors of a four-volume series) and Upp á sigurhæðir: saga Matthíasar Jochumssonar (The Biography of Matthías Jochumsson).

About the Author

The Works of Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir

Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir weaves herself in an interesting way into her latest novel Hvíti skugginn (The White Shadow, 2001). One of the main characters, Sólveig, is a visual artist who comes up with an idea for an artwork: to carve out shadows that people have thrown on snow, and then sell a picture of them to every shadow-owner:

People would remember the Hljómskáli Ice-shadow 2002. Around the neck of the shadow she would hang a sign with the individual’s personal identification number: Shadow of 250854 4209. (p. 97)

Actually, this particular personal identification number, or ID number, belongs to Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir, according to the population register. The fact that Þórunn makes herself a part of her own work, describes her attitude towards her fiction. It is personal but at the same time part of a larger picture; the character Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir belongs to the work, as does the author Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir. Therefore I think it safe to regard her fictional works as a unity. This view is supported by the fact that most of the main characters in Þórunn’s novels are women, and women narrate the stories.

Women and history are perhaps the two themes which immediately stand out upon first encountering the fiction of Þórunn; indeed, she is a female historian. In her first novel Júlía (Julia, 1992) it is the researcher/computer programmer/historian Ágústa who pieces together the story of the main characters, Júlía, Starkaður, Emil and Lena, a science-fiction narrative which mostly revolves around Júlía and Starkaður’s love and finally their destruction in a futuristic society. The novel Höfuðskepnur (Elements, 1994) is narrated and experienced through E., a female writer. E.’s life also provides the material for her writings, which approximates the form of the diary or letter, two favourite research materials of historians. Alveg nóg (Enough), a novel from 1997, also shows the main character, Guðrún’s, final accounting of her life trough a tragic narrative. Stúlka með fingur (A Girl With a Finger) is a historical novel (1999), set around and after the start of the 20th century, as told by the main character, Unnur. The research which Þórunn has done in order to give insight into the society of the past, has transferred on to Unnur, who displays a great interest in various academic subjects, while she fights to improve her position in a patriarchal society. Hvíti skugginn (2001) is probably the work which most goes against the aforementioned rule of Þórunn’s fiction. There are more main characters of both genders, an artist, literary theorist and a medical doctor. With the help of a special organization, The Hljómskálinn Organization, and the Internet, the new confession booth (a double meaning, of course), they remove the distinction between theory and its subject, making their own life their subject, similarly as in Höfuðskepnur.

We will not go into Þórunn’s numerous writings on history here, although one could point to many similarities between those and her fictional works. Many interesting threads in Þórunn’s oeuvre will also be left unmentioned or up in the air, while others are only mentioned briefly.

Perception and Circles

In her first work of fiction, the poetry collection Fuglar (Birds, 1991), Þórunn Valdimarsdóttir dresses in poetry the idea that human perception is tied to a circle, the horizon. The circle changes constantly:

mitt eigið land þar sem allt lætur að stjórn

leysist upp í sjóndeildarhringi[my own land where everything can be controlled

dissolves into horizons]

(“Hringurinn” (“The Circle”))

Human perception is like a red dot on a map which tells you that you are “here": “the red dot is where you are”, writes Þórunn (“Í gamla kirkjugarðinum” (“In the old churchyard”)). This vision may be associated with individualism, although it is not directly linked to political individualism. Þórunn’s vision is philosophical and as such it comes perhaps closest to solipsism. She demands much of the individual/subject, because he/she must constantly be constructing a new world picture around him/herself. Of course we conscious beings often cut corners by adopting ready-made world pictures from outside ourselves, but the work that goes into the construction of a world picture nonetheless happens every second. Of this Þórunn reminds the reader, in her poems, and not least in her fictional characters. Each world picture is accompanied by mythical stories, myths, which give it a logical foundation and justify it. Þórunn’s fiction is always working with myths, new and old. Each myth is under constant attack from other myths because the horizon of our consciousness is constantly clashing with other such circles:

lambhrútur í Suðursveit

skynugt kjöt í ull

telur sig hreyfanlegt fjall

fattar að hann er ekki vitund sjóndeildarhrings

þegar bíllinn æðir að honum[a ram lamb in Suðursveit

sentient meat in wool

thinks of itself as a movable mountain

realizes it is not the consciousness of the horizon

when the car speeds towards it ]

(“Hringurinn”)

This is how the circles of our consciousness clash, albeit not normally in such a direct and physical way as here.

In fact, it is more fitting in this context to speak of a three-dimensional space of each consciousness, rather than a flat circle. Unnur describes her space in the novel Stúlka með fingur like this, mixing the science of geometry with magic:

Sit with my legs beneath me, inside an imagined cube. It has six edges, the cube, eight angles, twelve sides, the amazing international intergalactic cube. I sit in the centre of it. If I count the heart, as the centre of my square, then there are six sides here and I, seven in total, eight angles and I, nine in total, twelve edges and I, thirteen in total. Here we have the incantation seven, nine, thirteen! [The cube] moves with me wherever I go […] it is my space. (p. 164)

Þórunn’s individualism/solipsism does not prevent the merging of two consciousnesses, although according to her this is rare, as the poem “Ást og þeir vessar” (“Love and those bodily fluids”) in Fuglar explains: “the universal clock / creates the fingerprints / working clocks with ten hands / none of them set the same […] then it shows mercy, the big anachronism, / and two sound together / in the same place / this insistent undertone / becomes a divine tone-devil / and an alcoholic drop falls / from the heavenly bodies”. To counteract the fate that no two consciousnesses are “set the same”, Þórunn introduces the idea of the four furies, the Greek furies, which in the novel Höfuðskepnur are given a new role (adopted from the author Madison Smart Bell, from his book, Doctor Sleep). The furies are personified as Poetry, Faith, Divination and Love, and in Höfuðskepnur they become headlines, one for each of the four parts of the book. In these four phenomena there seems to be a meeting of consciousnesses. The headline of the Faith chapter goes like this: “you are me / since I am for the most part water / and water is you” (p. 75). In the novel Júlía, where the furies also appear, there is a description of how love unites consciousnesses as Lena watches the lovers Júlía and Starkaður have intercourse. “Sees Júlía and Starkaður unite into one beast for this moment in time” (p. 67). The poem (poetry) unites the consciousnesses of the readers and the poetic voice (the poet): “green cells inside skin / an open sea of leaves / rainforest we are / at sunset intertwine / in a flame” (Fuglar, p. 30). The structure of Höfuðskepnur also points to such a union of reader and narrator. In the letter novel the reader becomes the “patron”, recipient of the letters as well as the love object of the author, E.

The furies all play a large role in Þórunn’s oeuvre. Poetry appears as fiction; the lyricism of Júlía, Höfuðskepnur and Alveg nóg recalls the poetry book Fuglar. Poetry is also the freest of the furies, the one that has been left most undisturbed by society’s institutions (Höfuðskepnur, p. 20). Love has been “locked inside” and hidden” (Höfuðskepnur, p. 20), and maybe for this reason finds its main outlet in fiction/poetry. Love is at least the subject matter of all of Þórunn’s novels. In Stúlka með fingur, love can unite the spaces of consciousness and the lack of love can divide them, as Unnur says: “I live in a cube. […] There is an invisible cube around J.J. He no longer wants to get into my cube” (p. 164). That faith plays a large role here may strike us modern people as peculiar, but faith is probably the most important aspect of myth and subsequently of the world picture of the individual/subject. “Life is stranger than fiction. It is a religious fable”, writes Þórunn in Alveg nóg (p. 18), and then repeats it at the end of Stúlka með fingur (p. 312). Faith requires sacrifices and martyrdom, both of which come up again and again in Þórunn’s novels. Thus, the death of Júlía (in an eponymous novel) is organized according to a complex sacrificial ritual of the Aztecs, which was aimed at extending the life of the sun. E. in Höfuðskepnur is raped, as is Unnur in Stúlka með fingur, and in a way the rape there is her sacrifice to God. It takes place aboard the livestock cargo ship The Bear during a great storm: “The only thing I think about is that the ship will sink for sure and the world is all going topsy-turvy and then remember that I had said to God that I would accept the next calamity if he saved the ship” (p. 257). Guðrún in Alveg nóg and Sólveig in Hvíti skugginn, suffer martyrdom, Guðrún by the loss of her daughter and Sólveig by her own death.

It is perhaps hardest to explain how Divination can unite two consciousnesses. Yet Þórunn equals divination with academic studies in Höfuðskepnur:

ber í barmi gráðugt kvenhjarta

hún Sundfríður með gullmittið

hennar séraukagrein er að hressa

daufa fræðimenn

sem synda í Vesturbæjarlauginni

og þykjast betri

með sín spáljóð[carries inside her chest a greedy female heart

Swimming Frida with her golden waist

her particular minor subject is to revive

dull academics

who swim in the West End Swimming Pool

and think they are superior

with their divination poetry]

(p. 23)

The role of divination might thus be to create a new consciousness, that is it unites the old consciousness of the individual/subject and a new one. Scholarship plays a large role in Þórunn’s fiction. She is herself a historian, as mentioned earlier, and has written books and TV series as such. Her fictional characters are often scholars or artists who use their art to organize their lives. One might say that Þórunn’s fictional characters, each in their own way, merge their different consciousnesses of various ages, and even those of others, like when Ágústa pieces together the life of Júlía in Júlía, and Sólveig tries to reconcile superstition with scientific scepticism in Hvíti skugginn.

Man and Animal

It is no coincidence that it is a ram that is at the centre of the horizon, which is being attacked by the car, in the poem I cited earlier. An important factor of Þórunn’s works is precisely man’s genealogical proximity to other animals on earth. Take these lines from Fuglar: “flies are related to humans” (p. 40), “in fact we are the same / a few mutating genes between us / both mammals / I a woman / you a feline” (p. 41). The reason is that Þórunn is quite preoccupied with Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution and how this theory confounded people’s ideas about themselves and God. Besides the abovementioned poetry lines, Fuglar also contains the poem “Galapagoseyjar” (“The Galapagos Islands”), about the place where Darwin made some of his most important discoveries, where giant turtles and marine iquanashave “now after million years / reached the form the islands demanded” (p. 42). In the novel Stúlka með fingur, which is set at the beginning of the 20th century, the main character (and narrator) Unnur is obsessed with Darwin and his theories: “Darwin sensed the incredible depth of the history of evolution and in this I find the strength to make his vision mine” (p. 196).

Darwin has a similar effect on Starkaður in Júlía, who invites to a dinner party a few historical figures from the past (Júlía is a future/science fiction novel where such things are possible), among them Darwin: “Darwin sees through everything like an opium user, and much, much deeper than the others. The first among humans to see the real magic of life which one can see if one peers into the nature of the biological world “ (p. 164). Darwin’s theory of evolution is a central myth in Þórunn’s world picture (if one can associate the world picture in her works with their author, and not the characters which she has created), and constantly reminds one of how little distance there really is between us humans and animals. Þórunn often writes characters like animals, or links them to animals in similes and metaphors. Emil and Starkaður are referred to as “male animals”, when they enter the story in Júlía (p. 38), and Starkaður asks Júlía “are you not yourself an animal who wants me to love you?” (p. 39) when they meet for the first time, and mingles animalism and love.

In Stúlka með fingur people and characters are often likened to animals, Unnur says for instance that she is a cat-like animal (p. 60), and cats also feature in Unnur’s view of society: “The classes who rule in this country, the rulers and their lot, I view as similar to cats” (p. 128). But the comparison that comes closest to the theory of evolution is when Þórunn compares human and primate society: “Humans are like animals, I can see it so clearly, we are human monkeys with ever improving weapons”, says Unnur in Stúlka með fingur (p. 94). This comparison reaches its apex in Höfuðskepnur – look at this comparison of the love life of humans and monkeys:

Humans are not most closely related to the monogamous, ethical gibbon monkeys, because unlike women, the gibbon ladies are always horny, so the gibbon males can satisfy themselves anytime.

Unfortunately we are most closely related to chimpanzees. Among these relatives of ours each male monkey presides over many female monkeys. For our cousins, the chimpanzee ladies have a lunar cycle, a reproductive cycle like us. (p. 59)

The centre of gravity in the life of E., the narrator and the heroine of the novel, is a baby chimpanzee who does not have a name, only Ape, because names “carry such a massive burden, a human burden, which fortunately should not be laid on a monkey” (p. 43). This monkey-like formula for names is also followed in Höfuðskepnur, by not giving characters any names. The centre of consciousness in the story is the only one who is given anything resembling a name, and it is only one letter, E. In the mother-child relationship of the narrator/letter writer E. and the monkey the theory of evolution has been reversed. The monkey is no longer the forefather of man, like the myth about Darwin’s theory “dictates” to us, but his offspring, the child of E. And it is not only in Höfuðskepnur that Þórunn throws man off the top of the evolutionary pyramid.

In her novel which is most concentrated on the relationship between a mother and her children, Alveg nóg, Guðrún, the heroine and narrator of the story, sees her daughter Lísa as a “wild child”, Lísa resembles a “bear coming up from a hole in the ice “ and is this “great little mind in its growing sheath of meat” (p. 60). Þórunn deconstructs the history of man to an even greater extent than biology itself has managed to do. Here we have also seen a good example of how a myth, which previously has toppled older myths, is revisited and recycled by Þórunn.

Perhaps one might say that Þórunn’s narrative method consists of precisely this, of recycling new myths from the old ones. Her inspiration comes equally from history and science, religion and fiction. A chapter from a historical book by Þórunn, Snorri á Húsafelli (Snorri at Húsafell, 1989), indicates this:

The scientific belief which followed the Enlightenment or rationalism shows, like all human phenomena, questionable symptoms if emphasised too strongly. The space which scientism gives to human perception is so tight that one might say it splits a centuries-old ideology, “the word of truth”, and eliminates the ambiguous powers of mysticism, symbolism and imagination. (p. 273)

Þórunn’s writing seeks to even out the distinctions which society has created between the different “academic” subjects by warning against putting too strong an emphasis on any one of them. In fiction we are used seeing symbolism, mysticism and imagination favoured over natural science, sociology and history, only to see the relationship reversed in all “official” discourse. Þórunn’s individualism is tempered by a generous dose of scepticism that sees something useful in all discourse, regardless of its position in society, while turning everything into myths she can work from.

The Grotesque

If one were to look for a theoretical term to describe Þórunn’s writing, “grotesque” is probably the concept, which first comes to mind. In that context, the animalism and beastliness (Jón Jakob says to Unnur in Stúlka með fingur: “remember that we have conducted ourselves as perfectly and innocently as beasts” (p. 304)) becomes a symbol of freedom, signifying freedom from human laws and constraints. Culture is a shock, as it says in Alveg nóg: “When you experience a trauma it is best to remember that you are an animal. They do not make too much of a fuss about things and they recover quickly. They also live as well as they can because there is no culture to confuse them” (p. 12). Freedom lies in discovering man’s animalistic freedom, and Þórunn expresses it best with bird symbols. The flight of birds is animalistic, but it is also beyond the abilities of man. Fuglar (Birds) is of course a title of Þórunn’s book of poetry, an indicator of the important place they have in her oeuvre, and in other works by her they also play an important role. In Júlía the flight of birds inspires an idea in the mind of the narrator, Ágústa, indicating that animal freedom is essential to fiction, to the story:

the small birds in my yard with their pattern stretch a joyful tent across the sky. […] They sweep off in a pattern, dozens of them, together as one and suddenly turn around […] The pattern that so many free individuals form together is amazing. [They] turn my eyes around so that an idea pours into the frame of my inner eye. (p. 181)

In fact, Þórunn’s fiction could be viewed as a pattern of free individuals. In Júlía, all the main characters are “untamed” and “independent”, against a (future) society that thrives on taming, making them a worthy material for a novel. Characters in other novels by Þórunn are also fighting against society’s taming efforts, although their fate is not to win that battle, with the exception of Unnur in Stúlka með fingur, who fights her way to more freedom that women usually had in the era where the story is set.

The grotesque in Þórunn’s works is not just present in the constant reminder that man is an animal. Her style of writing is also physical, in the sense that she writes candidly about man’s natural needs. Perhaps the reason for that can be found in E.’s attitude to writing in Höfuðskepnur: “Writing is so naked, I am more naked here at the computer than the little one in my lap” (p. 37). Man’s natural products also play a major role in the life of the mind, as shown in Stúlka með fingur when Unnur and Jón Jakob steal the faeces from underneath the farmhand Pálmi, in a very grotesque act: “He acts strangely in the next days. When one’s excrement disappears from underneath, men go crazy, stand up, look down, nothing, how stupid does the animal have to be when such emptying of the guts with by smell and everything is just an imagination” (p. 77). Not only does the grotesque change man into an animal, it also evens out the differences between people, as another example from Stúlka með fingur shows: Unnur as a horse-guide accompanies some distinguished foreign ladies, a mother and a daughter on a riding expedition: “The ladies have walked off out of sight and I accidentally go to the same place as they have, for the same purpose. During this brief moment as we crouch, shielded by our skirts, to answer the same need, all class divisions disappear, we are of the same species” (p. 58).

The grotesque vision includes a certain attitude towards death in Þórunn’s works. The grotesque makes death a part of the great cycle of life, where biomass (for want of a better word) is processed and recycled. This attitude is most apparent in the character of Þórunn in Júlía, when four characters make a mutual agreement about what should happen to their bodies after their death. Júlía, Starkaður, Emil and Aleister form a union around their wish to be buried without a coffin so that mourners can watch the plants the body turns into as it rots. Emil’s words show the religious element of this attitude, as he finds justification in world literature:

It may be Christian to go into the ground, but it keeps you in the same place. Straight lines, the coffin and the cross are left out. Union is the thing, an acknowledgement that man is one of the animals, and not the carrier of a very dangerous scared spirit who refuses to die, who roams around unfettered, tortured in hell or sick with sweet ennui. All the symbolism, Dante’s whole tour of the netherworld is real and belongs to life. Heaven is here too. (p. 89)

This animalistic, grotesque attitude to death is a subversion of what might be called the traditional worship of the dead body in our culture. Another example from Þórunn’s works can be found in Alveg nóg, when it keeps Guðrún from losing her mind after the death of her daughter, Lísa: “This happens to animals and they endure “ (p. 133). There is also a certain casual attitude towards Lísa’s body, it is granted a place in the text, just like the living Lísa. The animal-ness is given the status of a credo that joins heaven and hell on earth, and all living beings with it.

The emphasis on the cycle of life also falls on those acts that unite and have to do with the recycling and creation of live matter. We have mentioned the discharge of excrement and rotting, but the “positive” sides of the grotesque are the absorption of matter, through eating, and its creation, through sex. Food and food love have their role in Þórunn’s works; it is for instance perhaps no coincidence that Guðrún in Alveg nóg is a gourmet chef. The other positive side of the grotesque is also more prominent in Þórunn’s works, the one that has to do with sex and is often associated with eroticism. Because of my own discretion, however, I choose the word frankness about Þórunn’s writing, rather than the term eroticism. Þórunn is as frank towards sex as she is towards death and the discharge of excrement, and is given an equally mundane role in the text. Yet, sex is never far from love, which is very important to the grotesque, since it generates new life. Then there is sex which hurts, like the two rapes in Höfuðskepnur and Stúlka með fingur show. But when sex and love go together, they render abstract the line between consciousnesses, between consciousness and nature, even between life and death in the moment when new life can be generated. In Hvíti Skugginn sex and beauty go together in the mind of Sólveig:

Of course these are sex cries, she thinks when she goes outside again and hears the cries of the birds. How stupid she has been. Beauty is in sex [...] This beauty over the Pond rises from the groin. (p. 107)

And from the beauty of birdsong there is not a big leap into the beauty of art. Maybe all creation bursts forth from the groin; indeed that could be Þórunn’s central teaching.

© Unnar Árnason, 2003.

Translated by Vera Júlíusdóttir.

Articles

Articles

Neijmann, Daisy L., ed. A History of Icelandic Literature

University of Nebraska Press, 2007, pp. 465-466

On individual works

Alveg nóg

Dagný Kristjánsdóttir: “Du er hvad du gør” : de skriver om livet med udgangspunkt i døden og når frem til at [...] = “You are what you do” : they discuss life from the pont of view of death and come to the conclusion that [...].”

Nordisk litteratur 1998, pp. 70-71.

Stúlka með fingur

Preben Meulengracht-Sørensen: “Færøsk familiekrønike : islandsk kærlighedshistorie og hjemstavnsparodi = A family chronicle from the Faroes : a love story from Iceland, and an Icelandic parody on regional literature”

Nordisk litteratur 2001, pp. 42-46.

Awards

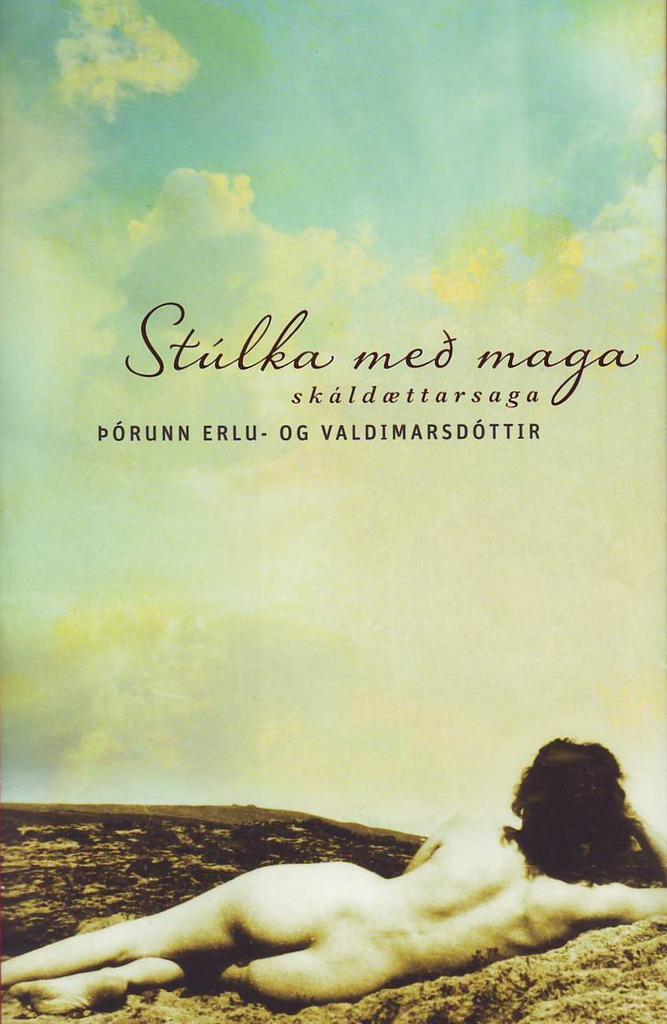

2013 – The Womens´ Literature Award: Stúlka með maga (A Girl With a Belly)

2011 – The Red Raven´s Feather: Dagur kvennanna – ástarsaga (Day of the Women – A Love Story)

2008 – The Icelandic Broadcasting Service´s Writer´s Fund

2006 – Upplýsing: The Icelandic Library and Information Science Association: Upp á Sigurhæðir. Saga Matthíasar Jochumssonar (The Biography of Matthías Jochumsson) As the best non-fiction book of the year

2000 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Stúlka með fingur (A Girl With a Finger)

1992 – First prize in a short-short story competition hosted by magazine Bjartur og Emilía: Short-short stories in Bjartur og frú Emilía 1, 1992

Nominations

2013 – DV Cultural Prize for literature: Súlka með maga (A Girl With a Belly)

2010 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (fiction): Mörg eru ljónsins eyru (The Lion Has Many Ears)

2007 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (fiction): Kalt er annars blóð (Cold Blood)

2006 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (non-fiction): Upp á Sigurhæðir. Saga Matthíasar Jochumssonar (The Biograpy of Matthías Jochumsson)

2007 – Hagþenkir (The Association of Authors of non-fiction and education material): Upp á Sigurhæðir. Saga Matthíasar Jochumssonar (The Biography of Matthías Jochumsson)

2001 – The Nordic Council´s Literature Prize: Stúlka með fingur (A Girl With a Finger)

2000 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (non-fiction): Kristni á Íslandi (Christianity in Iceland). As one of 5 authors in a 4 volume series

1989 – The Icelandic Literature Prize (non-fiction): Snorri á Húsafelli (Snorri at Húsafell: Biography)

1997 – DV Cultural Prize for Literature: Alveg nóg (Enough)

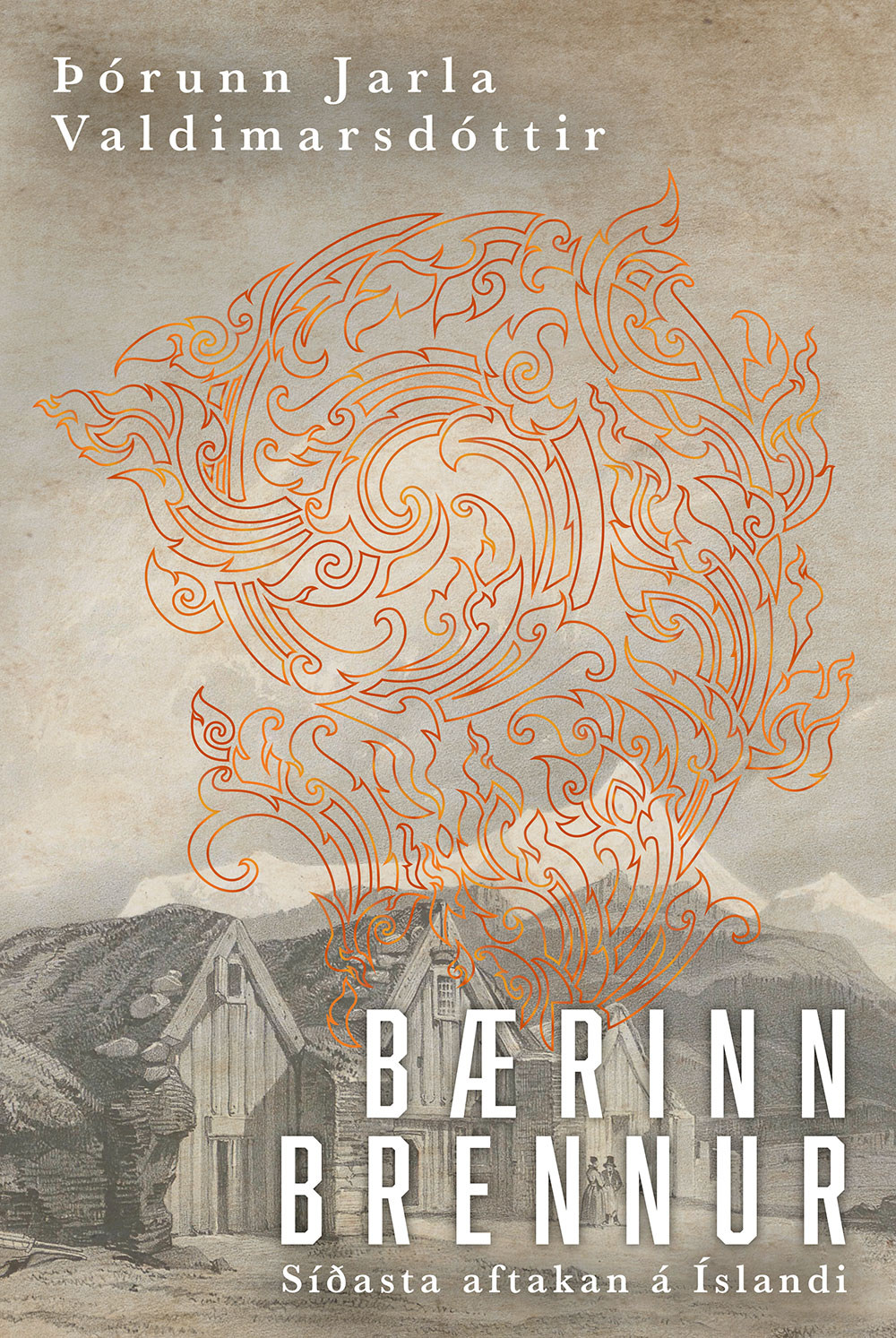

Bærinn brennur (The Burning of the Farm)

Read moreÁrið 1828 myrti Friðrik bóndasonur í Katadal nágranna sinn, bóndann og lækninn Natan Ketilsson á Illugastöðum í Húnavatnssýslu

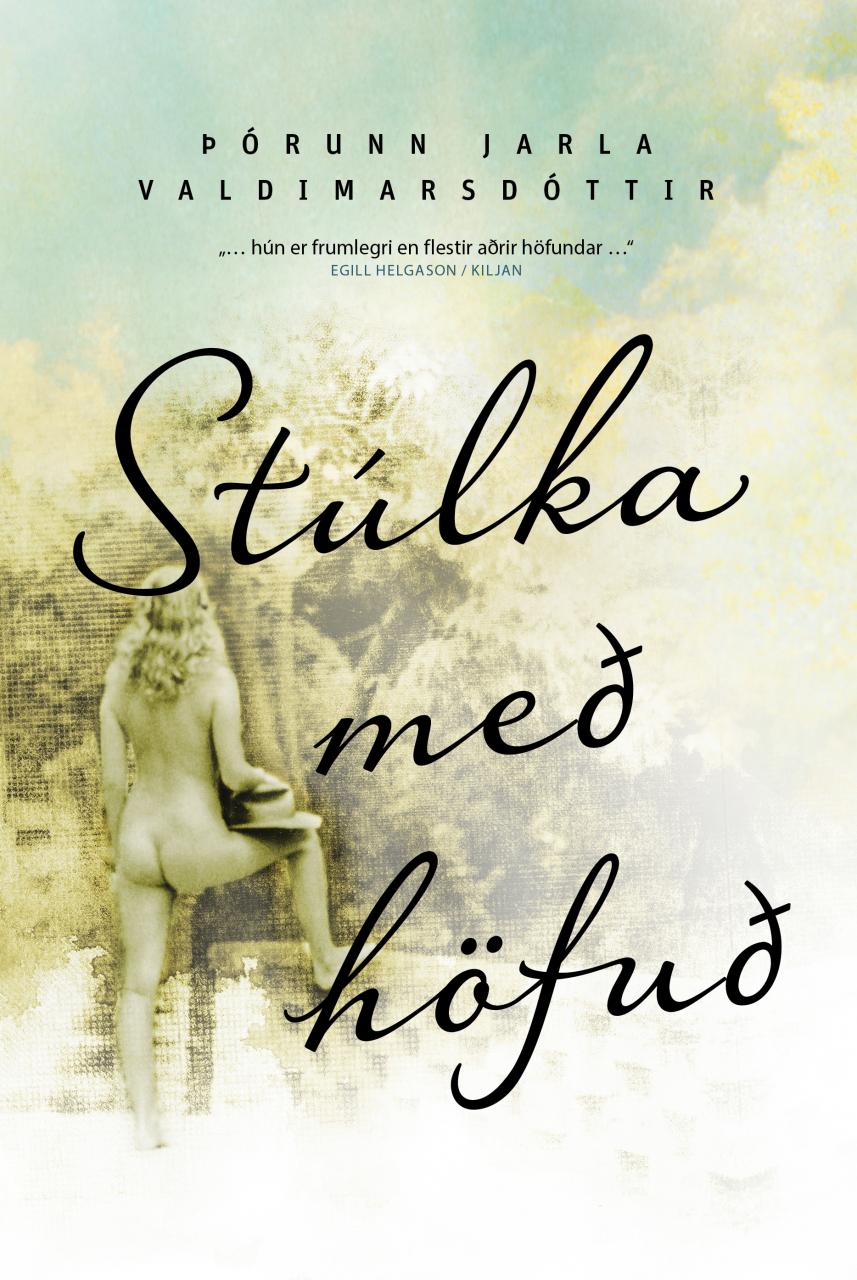

Stúlka með höfuð: sjálfsævisaga (A Girl With a Head: An Autobiography)

Read more

Stúlka með maga (Girl With a Stomach)

Read more

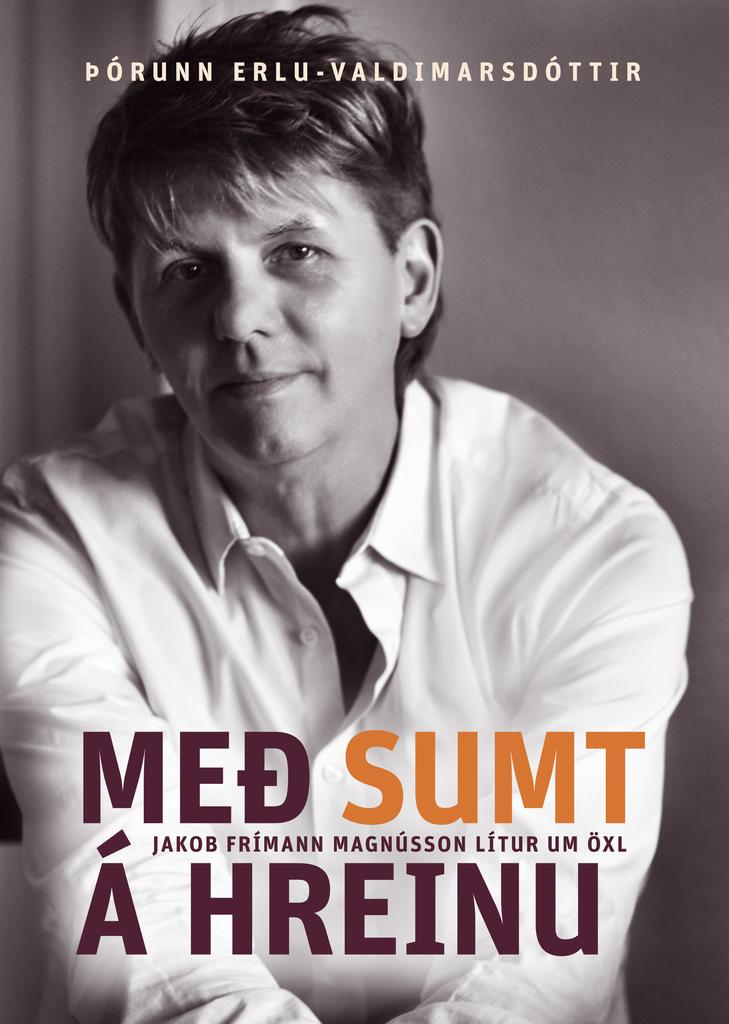

Með sumt á hreinu (Some Things in Order)

Read more

antennae scratch sky (scratch scratch)

Read more

Mörg eru ljónsins eyru (The Lion Has Many Ears)

Read more

Dagur kvennanna (Women's Day)

Read more

Loftnet klóra himin (Antennas Scratch the Sky)

Read more

Kalt er annars blóð (Cold is the Blood of Another)

Read more